|

Edgar M. Keller (September 12, 1867 to January 10, 1932) | |

Selected Covers (Hover to View) Selected Covers (Hover to View) | |

One of the more consistent and important artists of sheet music during the ragtime era was Edgar M. Keller, whose work spread well beyond the world of New York music publishing. He was born far away from the city at a time prior to the nascent field of dynamic cover illustrations. Edgar was the fifth of six children born to Prussian immigrant Henry Keller and his Irish-born wife Mary Margaret Kenny in Crescent (now Crescent City), Del Norte County, on the California coast line just south of Oregon. His siblings included George Martin (1859), William Arthur (1861), Joseph F. (1864), Laura (1865) and Mary Margaret (1870). The 1870 and 1880 enumerations taken in Crescent showed Henry to be a shoemaker and bootmaker respectively.

Edgar's mother, Mary Margaret, died in 1871, leaving Henry to raise his children alone. Laura died in 1875 at age 10, and young Mary may have been sent to reside with relatives as she did not appear in the 1880 record.

Edgar's mother, Mary Margaret, died in 1871, leaving Henry to raise his children alone. Laura died in 1875 at age 10, and young Mary may have been sent to reside with relatives as she did not appear in the 1880 record.

Given the lack of an 1890 census, it is unclear what Edgar may have been doing in his early twenties, but there is a good chance that he studied art and lithography with one or professionals during that period, even while still living in California. Keller moved to New York City in the late 1890s. While later one-paragraph biographies stated that he "turned to art in 1907," the 1900 enumeration both belies that and potentially explains his training through immersion. He was living in Manhattan with his bride, Nell Adams Clark, whom he had married in 1897, and was clearly listed as an artist. In that same building at 939 Eighth Avenue near the intersection of 56th Street, there were several artists residing there as well, consituting an artist's colony of sorts. It was also a mere two blocks away from the Art Students League of New York, which had been founded in 1875. So it is clear that Edgar was immersed in the artist's culture of New York, and Nell possibly went along for the ride, as she eventually took the craft up as well.

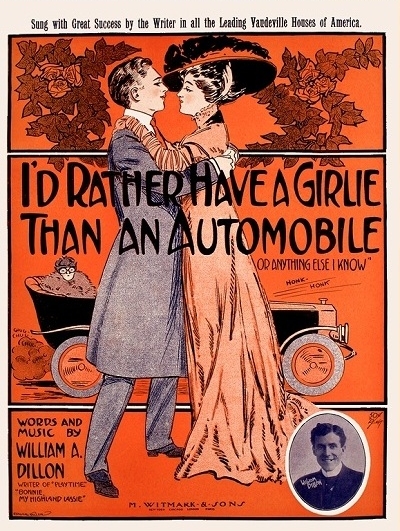

Edgar became versed in several different mediums, including etching, sculpting, oil and watercolor, and illustration. While in training to create his own style, and before he was widely exhibited, he went into the field of both book and sheet music illustration to provide a revenue stream. Some of his earliest work appeared in 1899 and 1900 for a couple of publishers, including Harry Von Tilzer. Then from mid-1900 forward Keller was employed by M. Witmark & Sons publications, and his fame spread from there. The Music Trade Review of July 6, 1901 notes that "Edgar Keller is permanently employed by [Witmark] and puts in his best work in this line." He would do cover work for Witmark more or less exclusively over the next decade. At 42 years of age, Edgar was profiled in the March 14, 1908, edition of the Music Trade Review:

When it is taken into consideration that M. Witmark & Sons publish a countless number of songs every year, and that of these some 90 per cent have color title pages, some idea may be gained of the amount of work which Edgar Keller accomplishes every twelve months. Yet he is never at a loss for an original idea. Year in and year out he has designed titles exclusively for Messrs. Witmark, who are always sure that Keller has something novel in reserve. Possessed of wonder natural talent, he has all the qualities which go to make the artist. His technical knowledge was acquired in the West, and the pride he takes in evolving some original form of lettering is only in line with his thoroughness in everything he attempts. Those of his numerous friends who visit his charming little studio uptown know that as a painter in oils he has done his best work. Personally he is a quiet reserved man with a high forehead and a finely cut boyish face. Very rare, indeed, does he express himself on any subject, but when he does offer an opinion it is always well worth listening to.

In addition to his work in sheet music, Keller illustrated some children's books, and created art and some verse for the New York Dramatic Mirror, an entertainment-related newspaper. By the early 1910s, if not earlier, both his oil landscapes and portraits were enjoying exhibitions in galleries and other places of prominence. Edgar managed to capture motion and light effectively, sometimes using very rough brush strokes, evoking more of a mood or ambience than realistically accurate renditions of his subjects. Although his music and magazine illustrations did not always have the same depth as his oils, they were still varied and appealing, usually including customized text that complemented the subject.

It appears that with his growing reputation in oils and exhibitions and commissions, Edgar possibly found sheet music illustration either less appealing or too time consuming, and after 1911 he was more or less out of the field. There are some covers brought into question that show up into the late 1910s issued by publishers other than Witmark with the Keller name on them. Some were provided by the artist on rare occasions (such as Laddie Boy), but it is uncertain if he was responsible for a few of them lacking his first name. The most evident reason for the sudden halt of covers is that Edgar became involved with Bison Film Company under Thomas Ince around 1912, and given a role as a technical and artistic advisor on Westerns and Civil War films. He was also employed as a set designer or background scene painter, among other duties, for a couple of months. However, in short order Keller became an actor, ultimately appearing in around two dozen silent shorts and features from 1912 to 1926, much of it with director Francis Ford. Edgar even tried his hand at directing The Yellow Girl in 1916. This meant travel back west as well, and it is probable that the Kellers were in San Diego, California, during the mid-1910s, then in Los Angeles through 1917. However, by 1918, Edgar was re-established in Manhattan, where the 1920 enumeration showed him running his own art studio.

In 1921, Keller spent a great deal of time in the Binghamton, New York, area, creating landscapes. One of them titled "The Black Pearl" received honors and a prominent exhibit. It showed "a hole in the ice on the Chenango River with the dark outlines of Mount Prospect and buildings on the far bank of the river, all casting an iridescent glow into the pool of dark water." Edgar had reportedly driven by the area and found it to be interesting enough to drop anchor for a while. In the mid-1920s, Edgar and Nell relocated to northern California, then spent some time in Portland, Oregon, where they were located for the 1930 census, both of them now working as artists in their own studio.

What was not revealed in the 1930 record was that Edgar, now nearly 63, was ill. Although the nature of his malady was not made known, some indications from scant records imply that it was either cancer or heart disease. Later in 1930 the couple went down to Hollywood, California, possibly to gain some work with the motion picture trade. However, Edgar became increasingly ill, and finally passed on in early 1932 at 64 years of age. He is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California. Nell survived him another 33 years, growing a reputation as a fine artist in her own right.