Abe Olman was born Abraham Olshewitz in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Julius Olshewitz from Russia and Carolina Goetz from Germany. His California death certificate indicates 1888 as the year, but his Social Security and military records tend to agree with an 1887 date, as do the census records on average. Abe's father was in the second hand furniture business in Cincinnati. He received nominal music training both in the school system and through private lessons. In the early 1900s Abe got a job as a traveling music salesman, schilling to stores in the Ohio/Kentucky/Indiana area. He had his first pieces published in Cincinnati by the stalwart publisher Sam Fox, including Moon Face in 1907 and Violetta in early 1908.

schilling to stores in the Ohio/Kentucky/Indiana area. He had his first pieces published in Cincinnati by the stalwart publisher Sam Fox, including Moon Face in 1907 and Violetta in early 1908.

schilling to stores in the Ohio/Kentucky/Indiana area. He had his first pieces published in Cincinnati by the stalwart publisher Sam Fox, including Moon Face in 1907 and Violetta in early 1908.

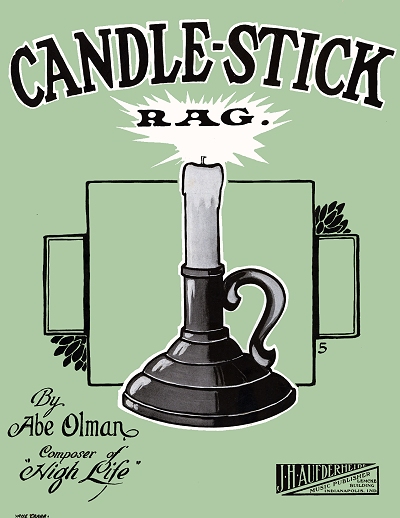

schilling to stores in the Ohio/Kentucky/Indiana area. He had his first pieces published in Cincinnati by the stalwart publisher Sam Fox, including Moon Face in 1907 and Violetta in early 1908.That same year found Abe in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he befriended a group of local musicians interested in composing ragtime. One of them, Will B. Morrison, who had already published Cecil Duane Crabb's piece Fluffy Ruffles, did the same with Olman's first rag, Honeymoon Rag. In 1909 his High Life was accepted by no less than the premier New York publisher Jerome Remick. Yet in 1910 he had Candle Stick Rag published in Indianapolis by John Aufderheide, father of his composer friend May Aufderheide, a deal likely arranged by the company manager and composer Paul Pratt. In the 1910 census Abe was lodging in Indianapolis, listed as a salesman of music. By this time he was working in the field for a couple of Chicago publishers. On one piece published in 1911, Hallowe'en (The Jack O'Lantern Rag), he inexplicably used a derivation of the reverse of his last name, Manlowe, which would be used again on a song in 1917 published outside of his employer at that time.

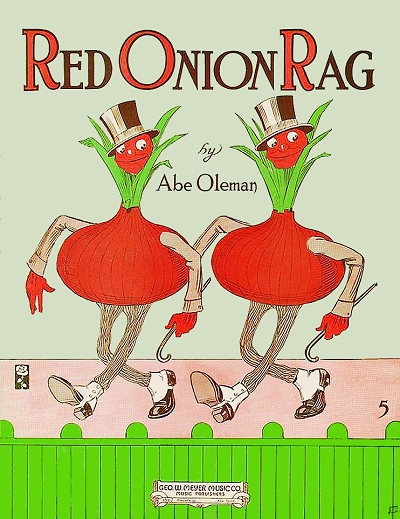

Olman finally made a leap of faith in 1912 and moved to Manhattan to make his way in publishing. His most famous and sophisticated syncopated piece, Red Onion Rag was published that same year by the firm that he managed from 1912 to 1913, the George W. Meyer Music Company. The company was actually backed by composer Gus Edwards (In My Merry Oldsmobile) who could not use his own name due to an existing contract with another publisher. Meyer's firm folded within two years, but not before Red Onion saw good circulation and caught the rapt attention of performers and publishers alike. It should be noted that both on some music covers (including Red Onion) and in the newspapers that his name was often seen spelled as Oleman, as opposed to the more correct Olman. But as long as the checks were all coming in to him, it was probably of little consequence. Abe hung around in Manhattan only a little bit longer, but had little output in 1913, spending part of the year in Europe performing and touring.

But as long as the checks were all coming in to him, it was probably of little consequence. Abe hung around in Manhattan only a little bit longer, but had little output in 1913, spending part of the year in Europe performing and touring.

But as long as the checks were all coming in to him, it was probably of little consequence. Abe hung around in Manhattan only a little bit longer, but had little output in 1913, spending part of the year in Europe performing and touring.

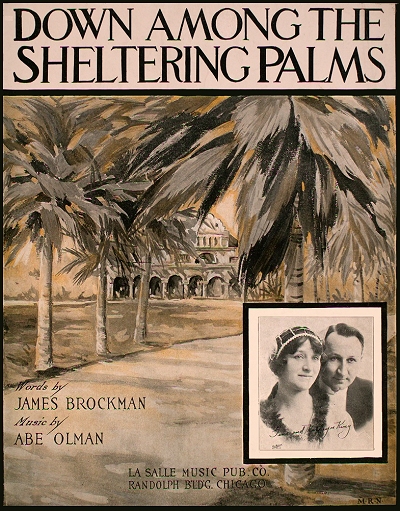

But as long as the checks were all coming in to him, it was probably of little consequence. Abe hung around in Manhattan only a little bit longer, but had little output in 1913, spending part of the year in Europe performing and touring.Olman finally went back to the Midwest and set up shop in Chicago in 1914 as the LaSalle Music Publishing Company, specifically to put out his newest song, Down Among the Sheltering Palms. With diligence and good salesmanship, Abe Feist ended up buwas able to plug the song to the point where it caught the attention of Manhattan publisher Leo Feist, who had a branch office in Chicago. ying the song in 1915 and handing it to no less than rising star Al Jolson for his latest stage production. An ad in the Music Trade Review noted that "It took a record smashing price to buy this song... Not a song that would have a 'fly-by-night' popularity; but a song destined to lasting favor from coast to coast." It quickly became "Al Jolson's Sensational Hit" selling over 3 million copies within a few years, and Olman's services were quickly in demand. But he did not go back to Manhattan so quickly staying in Chicago, and later back to Cincinnati for a while, putting out songs with a variety of lyricists, several with Ed Rose.

The year 1917, a particularly prolific one for Olman, found him back in Ohio, listed on his draft record as a traveling salesman working for Chicago publisher Forster, who was also taking on several of Abe's compositions. Among these was a ditty titled Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, O! with lyrics by Rose, which was handed to New York stage star and Ziegfeld Follies sweetheart Nora Bayes. She made this catchy tune an enormous success in short order, and it soon peaked 1 million copies in sales. It would rack up another million in the early 1940s after a 1939 revival of the piece by the Andrews Sisters on Decca. He also became an essential employee of Forster Music Publisher in Chicago. In late December, 1917, Abe enlisted in the Quartermaster's Department of the Army, but was not sent overseas during the war. Before the decade was out it was clear to Olman that Manhattan was ready for him, so he returned there for the bulk of his remaining writing and managing career. The composer also became one of the early members of ASCAP in 1920, where he would take a larger role in the future.

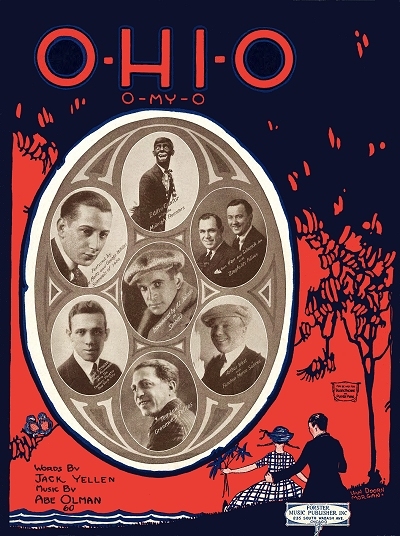

After an early 1920 operation for an unspecified problem and a short convalescence, the decade started out quite well for Abe. He became the general professional manager of Forster Music Publisher, a job he kept for at least most of the decade. Olman also had two songs interpolated into the 1920 Ziegfeld Follies. One of these, O-Hi-O (O-My!-O!), became his last major hit, but certainly set him up to be comfortable for some time. It was introduced by Al Jolson in Sinbad and quickly spread from there. Thanks to Jolson Eddie Cantor it became an enormous success, followed up with numerous piano roll renditions, and recordings by Jolson, Lou Holtz, clarinetist Ted Lewis, and famed vaudeville team Van and Schenck. It had another surge through a recording by the Andrews Sisters just after World War II, retitled Down By the O-Hi-O. This was just one of a series of songs written with lyricist Jack Yellen who had also worked for a time with composer George Cobb on several substantial hits in the 1910s. Abe was married in early 1922 to actress Mollie H. (Parker) Olman (stage name Peggy Parker), and they had one daughter, Marjory J. Olman, the following year.

Olman also had two songs interpolated into the 1920 Ziegfeld Follies. One of these, O-Hi-O (O-My!-O!), became his last major hit, but certainly set him up to be comfortable for some time. It was introduced by Al Jolson in Sinbad and quickly spread from there. Thanks to Jolson Eddie Cantor it became an enormous success, followed up with numerous piano roll renditions, and recordings by Jolson, Lou Holtz, clarinetist Ted Lewis, and famed vaudeville team Van and Schenck. It had another surge through a recording by the Andrews Sisters just after World War II, retitled Down By the O-Hi-O. This was just one of a series of songs written with lyricist Jack Yellen who had also worked for a time with composer George Cobb on several substantial hits in the 1910s. Abe was married in early 1922 to actress Mollie H. (Parker) Olman (stage name Peggy Parker), and they had one daughter, Marjory J. Olman, the following year.

Olman also had two songs interpolated into the 1920 Ziegfeld Follies. One of these, O-Hi-O (O-My!-O!), became his last major hit, but certainly set him up to be comfortable for some time. It was introduced by Al Jolson in Sinbad and quickly spread from there. Thanks to Jolson Eddie Cantor it became an enormous success, followed up with numerous piano roll renditions, and recordings by Jolson, Lou Holtz, clarinetist Ted Lewis, and famed vaudeville team Van and Schenck. It had another surge through a recording by the Andrews Sisters just after World War II, retitled Down By the O-Hi-O. This was just one of a series of songs written with lyricist Jack Yellen who had also worked for a time with composer George Cobb on several substantial hits in the 1910s. Abe was married in early 1922 to actress Mollie H. (Parker) Olman (stage name Peggy Parker), and they had one daughter, Marjory J. Olman, the following year.

Olman also had two songs interpolated into the 1920 Ziegfeld Follies. One of these, O-Hi-O (O-My!-O!), became his last major hit, but certainly set him up to be comfortable for some time. It was introduced by Al Jolson in Sinbad and quickly spread from there. Thanks to Jolson Eddie Cantor it became an enormous success, followed up with numerous piano roll renditions, and recordings by Jolson, Lou Holtz, clarinetist Ted Lewis, and famed vaudeville team Van and Schenck. It had another surge through a recording by the Andrews Sisters just after World War II, retitled Down By the O-Hi-O. This was just one of a series of songs written with lyricist Jack Yellen who had also worked for a time with composer George Cobb on several substantial hits in the 1910s. Abe was married in early 1922 to actress Mollie H. (Parker) Olman (stage name Peggy Parker), and they had one daughter, Marjory J. Olman, the following year.Olman also did some arranging in the 1920s, and one of his most famous arrangements was recorded and made famous by Ted Lewis, When My Baby Smiles at Me. While Abe kept composing with a number of famous or soon to be famous lyricists, he never quite captured that bubble of success again. Abe also formed his own publishing firm in New York City around 1923 and continued with it through the 1930s while maintaining his position with Forster. He also traveled from time to time to promote his songs and the Forster firm, even though some of his songs were in the hands of other publishers. It was said in the trade papers that Olman's shows, usually given at moving picture theaters, were "original and entertaining, and [have] brought his services in demand."

After having been based in Chicago for most of the 1920s, Abe is listed in the 1930 census as a music publisher in Manhattan. This status would change during the 1930s as he managed The Big Three publishing consortium, and after his own company was sold off. In the 1940 enumeration, taken in uptown Manhattan, Abe and Peggy still had their daughter Marjorie residing with them, and had added another daughter, Carolyn, around 1934. He was listed as a music publisher. Then Abe started working for the much larger firm of Robbins Music in Manhattan in the early 1940s, indicated on his 1942 draft record. That publishing house, at 799 Seventh Avenue, had been acquiring catalogs for some time, and with the absence of giant Jerome Remick who had sold off in the 1920s, Robbins became one of the largest in New York, along with Irving Berlin. Olman's position as general manager, and possibly arranger as well, served him well as he was able to afford a comfortable Riverside Drive address in Manhattan.

That publishing house, at 799 Seventh Avenue, had been acquiring catalogs for some time, and with the absence of giant Jerome Remick who had sold off in the 1920s, Robbins became one of the largest in New York, along with Irving Berlin. Olman's position as general manager, and possibly arranger as well, served him well as he was able to afford a comfortable Riverside Drive address in Manhattan.

That publishing house, at 799 Seventh Avenue, had been acquiring catalogs for some time, and with the absence of giant Jerome Remick who had sold off in the 1920s, Robbins became one of the largest in New York, along with Irving Berlin. Olman's position as general manager, and possibly arranger as well, served him well as he was able to afford a comfortable Riverside Drive address in Manhattan.

That publishing house, at 799 Seventh Avenue, had been acquiring catalogs for some time, and with the absence of giant Jerome Remick who had sold off in the 1920s, Robbins became one of the largest in New York, along with Irving Berlin. Olman's position as general manager, and possibly arranger as well, served him well as he was able to afford a comfortable Riverside Drive address in Manhattan.As a long standing member of ASCAP, Abe became the director of the organization from 1946 to 1956. While not directly active in performance or songwriting, Olman was directly engaged in looking after the needs of younger members and making sure they got their chance to make it in the industry as he had. Among his friends in the music industry was lyricist and performer Johnny Mercer who would found Capitol Records in 1942 with the same vision of giving a home to talented artists without being locked out by some of the larger companies looking for mainstream music. In fact, Olman gave Mercer his first big break in the songwriting field in 1944, recommending Mercer as a lyricist for a Dave Raksin tune called Laura that had come from the movie of the same name. While attempts had been made at the piece by veterans Oscar Hammerstein II and Irving Caesar, Mercer's lyric ended up winning over the composer and became an enormous hit. Abe and Johnny became long-time friends, and in 1969 Olman and Mercer, along with Abe's nephew Howard S. Richmond, co-founded the National Academy of Popular Music's Songwriters Hall of Fame to honor major contributions to American popular music. Looking at travel manifests it is clear that Abe also did quite a bit of traveling to Europe in the 1940s and 1950s, at times in an official capacity as the director of ASCAP.

Olman spent his retirement never quite completely retired, but engaged in many facets of advocating for the music industry, plus working for Howard who had started The Richmond Organization. His last decades saw him living in Southern California where the music industry had shifted in the 1940s, in part due to the rise of Capitol Records in Hollywood Died in Rancho Mirage, California. In 1983 he was honored with the Abe Olman Publisher Award, given out annually by his own Songwriter's Hall of Fame. The first recipient was Howie Richman, followed in 1984 by publisher Leonard Feist, and as recently as 2007 honoring rock entrepreneur Don Kirshner. However, the award's namesake only saw the first one handed out as he died in January of 1984 at the considerable age of 96, ending a career that spanned the whole of the growth of American popular music from Ragtime to Rock and Roll.

Compositions

Compositions