|

Albert William "Al" Brown (January 3, 1884 to November 28, 1924) | |

Known Compositions Known Compositions | |

|

1895?

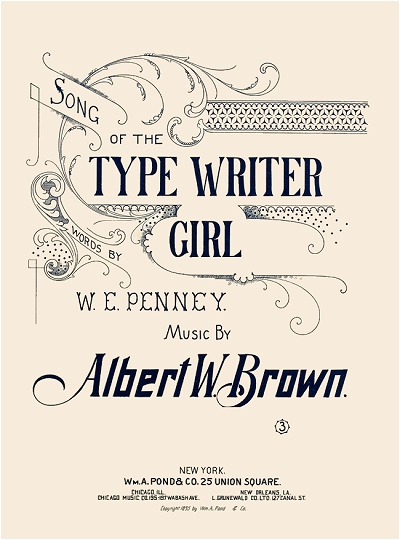

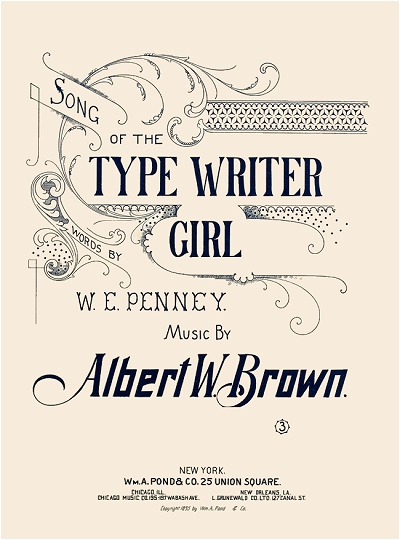

Song of the Type Writer Girl [1]1903

Skyrockets: Novelty Two-Step1904

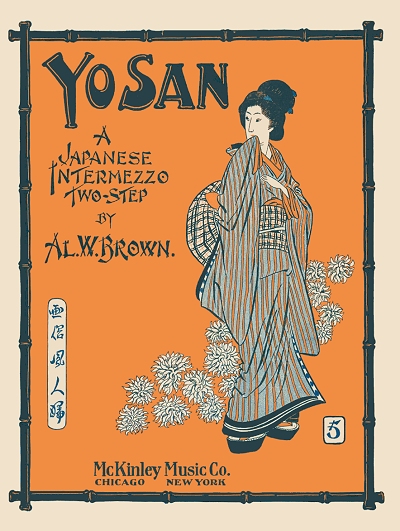

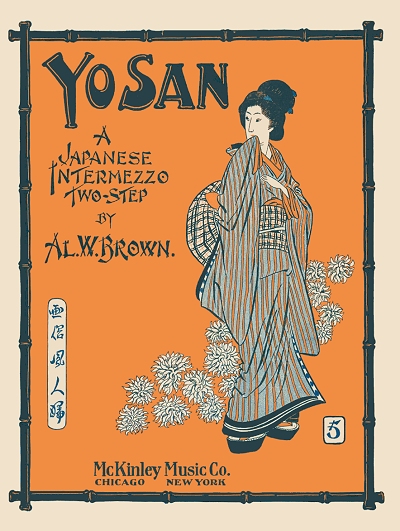

Suwanee Echoes: Waltzes—Rag Time NoveltyLouisiana Purchase Exposition March Yo-San: A Japanese Intermezzo Two-Step Cotton Field Dance: Characteristic March Arrival of the Mocking Bird: Intermezzo Loving Cup 1905

U.S.A. March1906

Sly Sal: A Simple Slow DragMary Ann, I'd Like to Be Your Man [2] 1907

Georgia Sunset: A Southern Tone-PoemI'd Like to Call On You [3] Poor Old Girl [3] When Vacation Days are Over [3] Pondering [4] Would You Like to Love a Boy Like Me? [4] 1908

Kiss MeHoneymoon Three Step Base-Ball [3] To-Night [3] Under the Electric Lights [3] Roll on the Rollaway: The New Roller Skating Craze [3] Daylight Hurts My Eyes [5] 1909

Sociability: March and Two-StepI'll Be With You Bye and Bye You're the Only One I Love The Old Red Barn: Barn Dance The Gaiety: A New Dance Take Me Back to Kidland [2] Come Down, Nellie, to the Old Red Barn [3] The Same Sweet Girl [3] I Want to Go to the Ball Game [6] Baseball Ditties [6] Those Grand Old Words, "Play Ball!" In Wise King Solly's Days Root! Root! Root! This Sweet of Mine Baseball Fans Theirs is a Glory that Lasts But a Day 1910

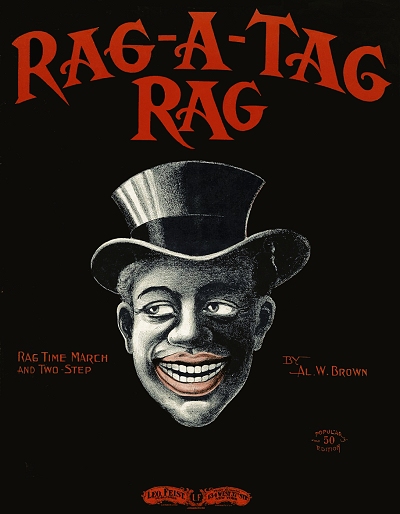

Rag-a-Tag Rag: Ragtime March and Two-StepThat Yodlin' Zulu Rag [7] Any Old Time or Any Old Place [7] In My Old Home Town [7] Plain Little Country Girl [7] Lets Get Spooney Awhile [7] Don't Forget Me Dearie [7] Go On, Good-a-Bye: Italian Character Song [8] Sweet Angel Eyes [9] My Zouave Soldier Boy [10] 1911

I'm Awfully Glad the Girl I Had Has FoundAnother Beau [7] My Todalo Man [7] The Whole World Reminds Me of You [7] Let Me Spend My Vacation with You [7] Phantom Rag [11] 1912

Back in Those Old Kentucky DaysMadison The Judge He's-a-Irish Too [7] Remember Me to My Old Gal [7,12] 1913

When You're TravelingThe Moving Man [4] I'd Like to Borrow a Kiss [4] A World-Wide Romeo [4] What's the Greatest Thing in the World? [13] The Man with Three Wives: Musical Comedy [4] Hello! Hello! The Tale of the Jealous Cat The Passing Show of 1913: Musical Revue [4] Foolish Cinderella Girl My Irish Romeo Ragging the Nursery Rhymes That Good Old-Fashioned Cake-Walk In the Life of a Working Girl Inauguration Day Romance Land A Melodrama Known as Married Life Whistling Cowboy Joe Pauline Strongheart Florodora Slide Fine Feathers Gate of the Golden West 1915

No One Can Keep You Away From MeYour Daddy Was a Bashful Beau [14,15] At the Fountain of Youth [14,15] 1916

Melodyland: Musical Comedy [3]Mother Goose: Musical Comedy [3] Flower of My Life (Fleur de ma Vie) [16] |

1917

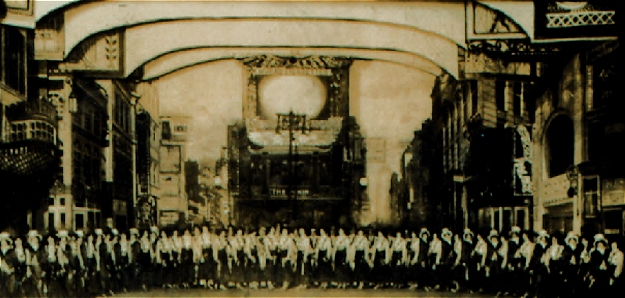

Night SchoolKeep On Smiling, Mr. Moon Man Ragtime Will o' the Wisp Like the Lovers in the Story Books My Gal of the Southland, My Dixie Rose Fickle Little Melody [3] It Took the Stork to Deliver the Goods [17] There's a Service Flag Flying at Our House [17,18] 1918

You're in Style When You're Wearing aSmile [5,19] My Girl of the Southland [17] Jackie Boy [17,20] The Bravest Battle of the War Was Fought in a Mother's Heart [17,21] Go Over the Top with Reilly [17,22] Liberty Bell, Ring On! [23] Little Blue Bonnet [23] I Am Dreaming of Tomorrow and You [23] Goodbye Dear Old Girl [23] E-Yip-Yow! Yankee Boys Welcome Home Again [24] My Irish American Rose [25,26] 1919

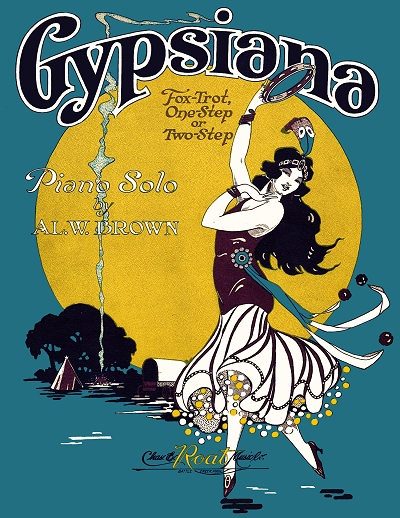

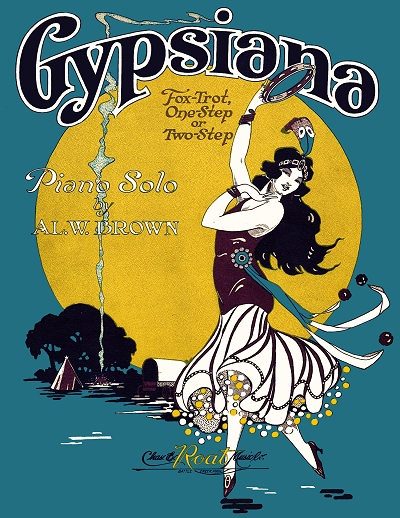

Gypsiana: One-StepThe Hare Hunter: One Act Musical Goodbye Dear Old Pal [23] Off with the Sad Days, On with the Glad Days [23] I'm Getting Tired of Playing Second Fiddle [23] Down in Echo Valley [23] You'll Like It: Musical Revue [23,27] When the First Girl You Love Says, "Good Bye" What Do You Mean? All Alone There's a Reason 1920

Gypsiana: Oriental Episode [23]1921

Dream Waltz Blues [25,26]Oriental Temple Blues [5,28] That's Apple Sauce [31] 1922

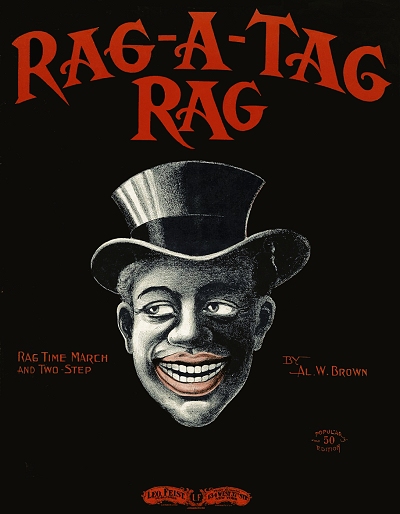

Broadway Brevities of 1922: Musical RevueMagazines [32] Mystery [32] Washington's Calling Me [32] Dearie You SHould Have Been With Us [33] Rose Of Italy, She Waits for Me [33] Patches of Auld Lang Syne [34] Tiny Chinese Doll [34] My Pretty Sweet Sixteen [34] 1923

Broadway Brevities of 1923: Musical RevueIt Happened in Normandy: Musical Revue When the Curfew Rings at Nine Magic Waltz [28,29,35] As Soon As I Get Yoou Off My Hands (I'll Be On My Feet Again) [36] Ireland, Dear Ireland, Land of My Dreams [37] Scandal on the Farm [38] Scandal of the Flowers [38] Ain't it a Shame [39,40]

1. w/W.E. Penney

2. w/Mae Sheehy 3. w/Roger Lewis 4. w/Harold Richard Atteridge 5. w/Gus Kahn 6. w/C.P. McDonald 7. w/J. Brandon Walsh 8. w/M. Joseph Murphy 9. w/Tell Taylor 10. w/May Rerdelle 11. w/Sol Ginsberg as Violinsky 12. w/George Moriarity of the Detroit Tigers 13. w/Collin Davis 14. w/Alex Gerber 15. w/Gertie Moulton 16. w/Frank Tyler Daniels 17. w/Thomas P. Hoier 18. w/Bernie Grossman 19. w/Egbert Van Alstyne 20. w/Eugene West 21. w/Corp. Paul Boggs, U.S. Army 22. w/Joseph M. Leahan 23. w/Haven Gillespie 24. w/Bob F. Sear 25. w/Andrew B. Sterling 26. w/Arthur Lange 27. w/Joseph T. Burrowes 28. w/Walter Hirsch 29. w/Erwin R. Schmidt 30. w/Sam Beverly 31. w/Herman Kahn 32. w/John Hyman 33. w/Billy Dunham 34. w/Will J. Harris 35. w/Jack Yellen 36. w/James Brockman 37. w/Ethel Steele 38. w/William A. Downs 39. w/W.A. Hann 40. w/Joseph Simms |

Al W. Brown could be considered to some degree a working-man's composer and performer, one who wasn't particularly prominent, but wasn't in the background either. Capable and competent, but not top of the field. Willing to put in the effort when required, but also prone to failure now and then. His name is not commonly heard among ragtime era composers, but known to a few fans of his work. As a result of his limited public exposure, very few details about his early life are known, but what could be extracted is presented here.

As a result of his limited public exposure, very few details about his early life are known, but what could be extracted is presented here.

As a result of his limited public exposure, very few details about his early life are known, but what could be extracted is presented here.

As a result of his limited public exposure, very few details about his early life are known, but what could be extracted is presented here.Albert was one of two children born to William J. Brown and Mary Magdalena Hendricks in Cleveland, Ohio, the other sibling being his older brother James (3/3/1882). It appears that Albert spent most of his formative years in Cleveland, but no information was available as to what type of musical training he had. There is a possibility that he received some formal training of some kind even before he was ten. In 1895, when Albert was eleven-years-old, a piece was issued by Wm. A. Pond, probably from their Chicago, Illinois, office, called Song of the Type Writer Girl. It was a mildly simple and trite 6/8 melody written to the poem of the same name by William Edward Penney that was originally published around the United States in 1891. There were no other composers found in the 1890s, in Chicago or elsewhere, that used either Albert W. Brown or even Albert Brown. Even though the harmony of the second half of the piece is a bit more sophisticated than the melody, indicating perhaps a more experienced arranger, there remains the possibility that it was the same Albert W. Brown, potentially a child prodigy, who submitted this work and was fortunate enough to see it in print. Until there is evidence to the contrary, this will be accepted as a probability. Why it emerged in Chicago instead of Toledo, Ohio, or Detroit, Michigan, also growing publishing centers and closer to Cleveland, is probably because that is where the poem originated. If the tune was submitted by mail (and it may possibly have very well been part of some songwriting competition launched by a newspaper), the location would have been irrelevant, as would his age. It should be noted that the actual "Type Writer Girl" was the beautiful 18-year-old Mary Postgate, a court stenographer and the daughter of prominent Chicago newspaper editor John W. Postgate. She was the one to whom the poem was dedicated.

The Brown family could not be readily located in the 1900 census. It is possible that around this time the family was falling apart, as Mary would soon be divorced from William. The next sighting of Albert was in 1901, now 17, where he was listed in the Chicago city directory, living on State Street, and working as an actor. He may have been trying to break into the local vaudeville theaters, and was soon successful, playing bit parts, singing a bit, and playing the piano. Within a few years this would translate to a national exposure on various vaudeville circuits. Al's next (or first) known composition was the instrumental dance tune Skyrockets in 1903. The following year would see several numbers penned by Brown make it into print, including a march honoring the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair) in Saint Louis, Missouri a pseudo cakewalk/almost rag - Cotton Field Dance; a stereotypical Asian dance intermezzo - Yo San; and a competently syncopated well-developed ragtime waltz - Suwanee Echoes. [Note that in musicological terms and by common definition that ragtime is a 2/4 or duple meter style, not a waltz, but that this term was applied to a few syncopated 3/4 works.] The latter proved rather popular, and gave Brown's name some import in the business.

He may have been trying to break into the local vaudeville theaters, and was soon successful, playing bit parts, singing a bit, and playing the piano. Within a few years this would translate to a national exposure on various vaudeville circuits. Al's next (or first) known composition was the instrumental dance tune Skyrockets in 1903. The following year would see several numbers penned by Brown make it into print, including a march honoring the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair) in Saint Louis, Missouri a pseudo cakewalk/almost rag - Cotton Field Dance; a stereotypical Asian dance intermezzo - Yo San; and a competently syncopated well-developed ragtime waltz - Suwanee Echoes. [Note that in musicological terms and by common definition that ragtime is a 2/4 or duple meter style, not a waltz, but that this term was applied to a few syncopated 3/4 works.] The latter proved rather popular, and gave Brown's name some import in the business.

He may have been trying to break into the local vaudeville theaters, and was soon successful, playing bit parts, singing a bit, and playing the piano. Within a few years this would translate to a national exposure on various vaudeville circuits. Al's next (or first) known composition was the instrumental dance tune Skyrockets in 1903. The following year would see several numbers penned by Brown make it into print, including a march honoring the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair) in Saint Louis, Missouri a pseudo cakewalk/almost rag - Cotton Field Dance; a stereotypical Asian dance intermezzo - Yo San; and a competently syncopated well-developed ragtime waltz - Suwanee Echoes. [Note that in musicological terms and by common definition that ragtime is a 2/4 or duple meter style, not a waltz, but that this term was applied to a few syncopated 3/4 works.] The latter proved rather popular, and gave Brown's name some import in the business.

He may have been trying to break into the local vaudeville theaters, and was soon successful, playing bit parts, singing a bit, and playing the piano. Within a few years this would translate to a national exposure on various vaudeville circuits. Al's next (or first) known composition was the instrumental dance tune Skyrockets in 1903. The following year would see several numbers penned by Brown make it into print, including a march honoring the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair) in Saint Louis, Missouri a pseudo cakewalk/almost rag - Cotton Field Dance; a stereotypical Asian dance intermezzo - Yo San; and a competently syncopated well-developed ragtime waltz - Suwanee Echoes. [Note that in musicological terms and by common definition that ragtime is a 2/4 or duple meter style, not a waltz, but that this term was applied to a few syncopated 3/4 works.] The latter proved rather popular, and gave Brown's name some import in the business.By 1905 Al was on the road with a couple of smaller vaudeville companies touring the Midwest, usually touted as part of the song and dance team of [Al] Brown and [Lew] Cooper as the song part. His output was still relatively sparse, but his significant works of the period included Sly Sal and the descriptive ragtime tone poem Georgia Sunset. While on the road in Ohio, Albert was married to Edna Florence Faraba in June of 1907. Their union would last around two years before they were divorced. From 1907 to 1909 Al's output would increase somewhat, having found two relatively prolific and talented Chicago partners to provide him with lyrics, Roger Lewis and Harold R. Atteridge. With yet another writer, C.P. McDonald, he would write a baseball song that seemed poised to ride on the coattails of the highly-popular Take Me Out to the Ball Game of 1908. However, I Want to Go to the Ball Game simply did not catch on in the same way, languishing with dozens of other such tunes from around the country. With McDonald he would also produce a folio of six other baseball-themed ditties, probably intended for vaudeville acts. A number of engaging instrumentals by Brown also found their way into print via Chicago publishers.

The 1910 census taken in Chicago found Al living with his divorced mother and a divorced "lodger," Peter Pinter, who would actually soon be his stepfather. Al also showed as divorced, and working as a composer of music. His Rag-A-Tag Rag was issued in 1910 along with a number of other interesting songs, most composed with new partner J. Brandon Walsh. Since 1905 he had been part of the vaudeville team of Brown and Cooper, with Al as the instrumentalist and Cooper as the dancer, both singing current popular songs, including Al's, in, according to some reviews, nearly sublime harmony. A review of the team from the November 2, 1907, issue of Variety touted the team's vaudeville debut in New York City:

His Rag-A-Tag Rag was issued in 1910 along with a number of other interesting songs, most composed with new partner J. Brandon Walsh. Since 1905 he had been part of the vaudeville team of Brown and Cooper, with Al as the instrumentalist and Cooper as the dancer, both singing current popular songs, including Al's, in, according to some reviews, nearly sublime harmony. A review of the team from the November 2, 1907, issue of Variety touted the team's vaudeville debut in New York City:

His Rag-A-Tag Rag was issued in 1910 along with a number of other interesting songs, most composed with new partner J. Brandon Walsh. Since 1905 he had been part of the vaudeville team of Brown and Cooper, with Al as the instrumentalist and Cooper as the dancer, both singing current popular songs, including Al's, in, according to some reviews, nearly sublime harmony. A review of the team from the November 2, 1907, issue of Variety touted the team's vaudeville debut in New York City:

His Rag-A-Tag Rag was issued in 1910 along with a number of other interesting songs, most composed with new partner J. Brandon Walsh. Since 1905 he had been part of the vaudeville team of Brown and Cooper, with Al as the instrumentalist and Cooper as the dancer, both singing current popular songs, including Al's, in, according to some reviews, nearly sublime harmony. A review of the team from the November 2, 1907, issue of Variety touted the team's vaudeville debut in New York City:This is the Brown and Cooper's first real New York showing, although they have played several Sunday concerts here-abouts. Cooper has appeared at intervals during the last year with a various assortment of partners. In his present team mate he seems to have struck about the right party. Brown has a nice appearance, a good voice, although not quite as good as he thinks it, and altogether has the makings of a tip-top straight man. At present he is inclined to over play. It may be the effect of the new material, or of the new partner; at any rate Cooper has improved a hundred per cent, since last seen. His Hebrew dialect is not dropped for a moment, and he is acquiring a style distinctly his own, although his appearance suggests his brother Harry strongly. The talk is fairly bright, and there are one or two new bits of business introduced which won solid laughs. The parodies as well as the song used by the "straight" man could be bettered. There is a third party employed in a small way, who is just about good enough to be carried along. When the pair acquire an easy stage presence they should find desirable time.

Al and Lew toured the west coast venues in 1910 and 1911. On the second tour they were also engaged with the female team of Mendis and Moulton, the latter being Gertrude Virginia Moulton. The professional engagement turned into a personal one which culminated in a marriage on July 11, 1911. However, this union also seemed doomed, as by 1913 both were single once again. Being on the road seems to have limited Al's capacity to write much beyond what was used in the act, but he did turn out a handful of works from 1911 to 1912. By that time, he and Lew had broken up their act, and Al spent more time at home in Chicago, occasionally going to New York for performances or professional contacts.

|

Where Al went or what he was doing in 1914 is unclear. He may have simply taken some time off after the rigors of working and reworking the large 1913 production, as well as recovery from his second divorce. There were no known compositions from him registered that year. He eased back in to the business in 1915, dividing his time between Chicago and New York City. Among the productions he was involved with included Merry Moments, a free show that was part of the dining experience at Reisenweber's Restaurant on Columbus Circle. (Within the next two years, some of the first ensemble jazz heard in New York would emerge from the same venue.) He was prominently mentioned in a Variety review of the show in their December 31, 1915 edition:

"Merry Moments… was produced by Ned Wayburn, runs in two sections, tastily costumed, and is much longer than the customary show of this sort. It is likewise much better. That it is both is almost wholly due to the main principal in it, Al B. White, a good and clean looking young fellow who hasn't a rival as a revue leader. If there is a better general cabaret entertainer than he is, this city hasn't seen him… There are three or four other principals and eight chorus girls. (Miss) Bobby Folsom is second to White. She sings several numbers and should develop. The girl has ginger, looks nice enough, but needs a little tuition… The best songs were "The Rocky Road to Dublin" (White), "Wibbly Wobbly Walk" (Miss Folsom), "20th Century Rag" (White), "Open and Close the Door" (Yiddish) (White), "Is There Still Room for Me 'Neath the Old Apple Tree?" (White), "No One Can Keep Me Away from You" (White and Folsom), "Hello. Hawaii, How Are You?" (Folsom), "Paris" (White). There are 22 numbers in all.… Al W. Brown composed the specially written music. He wrote the "No One Can Keep You Away from Me" number that is quite pleasing. Mr. Brown also leads the orchestra, more difficult than may be imagined in this odd shaped room for a show. The musicians are at the far end. It is trying for them to follow a singer, so far away, as the music drowns out the voice, but they do exceptionally well. The two Reisenweber orchestras are combined for the free show period… Reisenweber's, in the ball room, has secured a neat light effect in an unique way, getting the same effect very simply that many of the restaurants only have secured after dotting the walls and ceilings with hundreds of colored incandescents. It's worth a trip to Columbus Circle to see this "Merry Moments" show. It easily runs ahead of any free revue New York has had.

Merry Moments kept Al engaged into March of 1916. He then co-wrote two separate musical comedies in 1916 with Roger Lewis, both of them whimsical looks at childhood in some regard. Based on continuing advertisements, both Melodyland and especially Mother Goose were relatively successful entertainments and alternatives to the pricier Follies brand of show. In the middle of the year he teamed up with Bobby Folsom for a vaudeville act that the pair continued into 1919. The Great War in Europe, of course, largely occupied the country by that time, and as with most composer, Brown contributed a couple of pieces into the large pot of war-themed songs. On his draft record, submitted in Chicago during the last call of September 12, 1918, he noted that he was still residing with his mother and stepfather, and working as a vaudeville performer and pianist at large with his own team of Folsom and Brown. That year had been a particularly prolific one for Al, including some more war numbers, one of them highly sentimental, and the last of them touting the American victory and the return home of the Yankee soldiers.

Backing down from the vaudeville travel in 1919, Brown wrote at least two musicals in addition to a few songs. The Hare Hunter, the heavily advertised one-act produced by and starring Harry Welton and Marjorie Marshall, with the entire score by Al, did moderate business in New York and on the road. This was followed by a musical revue combining a number of stage songs from other shows by other composers with five of his own pieces penned with lyricist Haven Gillespie to a book by Joseph T. Burrowes, the latter who may have also been an associate producer. Touted as an "All Chicago Revue" with the optimistic title of You'll Like It, it turns out that most of the Chicago and New York reviewers of the production had the opposite reaction. One example was found in the New York Clipper of May 28, 1919:

"You'll Like It" … was given its first performance last night at the Playhouse and proved to be one of the least entertaining shows this city has ever seen. It is, in fact, the weakest thing put on the Chicago stage since "When the Rooster Crowed," with which it vies for first place in the unentertaining class.

The piece is the work of Joseph Burrowes and Al W. Brown who, in lieu of anything like a book, have strung together brief travesties of successful stage works, including "Chu Chin Chow," "The Riddle Woman," "Scandal" and "The Masquerader." Between these burlesques, songs and dances were given by Irene Williams, Bobbie Folsom, Valerie Walker, Paul Rahn, Mis Fung Gue and Harry Haw. Among the others in the show were Al Fields, who worked hard with his material. But even his cleverness availed little. Lydia Barry and Morton and Moore were in the same boat as Fields.

Likely discouraged by this reception, another period with no copyrights from Al W. Brown followed. The only 1920 issue was of his 1919 intermezzo Gypsiana adapted into a song. The 1920 enumeration taken in Chicago still had Al residing with his mother and stepfather, listed as a music writer. However, he would soon permanently relocate to New York City. Once there in mid-1921, Brown established a studio near Broadway with the intent of working as a contractor to either write or musically direct shows, as per his running advertisements in Variety and other papers:

However, he would soon permanently relocate to New York City. Once there in mid-1921, Brown established a studio near Broadway with the intent of working as a contractor to either write or musically direct shows, as per his running advertisements in Variety and other papers:

However, he would soon permanently relocate to New York City. Once there in mid-1921, Brown established a studio near Broadway with the intent of working as a contractor to either write or musically direct shows, as per his running advertisements in Variety and other papers:

However, he would soon permanently relocate to New York City. Once there in mid-1921, Brown established a studio near Broadway with the intent of working as a contractor to either write or musically direct shows, as per his running advertisements in Variety and other papers:Dear Friends:— A Line or so, to let you know I've opened up a studio; where I will write a song that's bright, for any situation. My stuff you see, I guarantee, arranging is my specialty; and furthermore, I'll make and score, a perfect orchestration.

You know, a skit to make a hit, should have a special song in it, and I invite you day or night, to call when you're in town, for now and then stuff from my pen is relished by the booking men.

My name insures, Sincerely yours, Al. W. Brown, 148 W. 45th St.

Al was successfully engaged for both the music and lyrics ot the 1922 edition of the musical revue Broadway Brevities, calling on the magazine of the same name as its premise. Debuting at the Winter Garden Theater in New York in the summer where it ran for 18 weeks, followed by a similar stint in Chicago, it went on the road in December on the Columbia Theater Circuit to great acclaim. Touted as a "big girly revue," it made Brown a popular entity once again. It was noted in the July 4, 1923 edition of Variety that Al had been engaged by producer Eddie Daley not only for the Broadway Brevities of 1923, which he managed to complete, but for a new show called Runnin' Wild. The latter property soon went to George White and was famously completed by James P. Johnson, Aubrey L. Lyles and R.C. McPherson (as Cecil Mack). Whether Brown could have come up with something to equal the popular of Johnson's tune The Charleston is probably not up for debate. However, the 1923 edition of Broadway Brevities met with only a little less success than 1922.

On November 30, 1923, Al was married to Pennsylvania native and singer Ethel Steele in Manhattan, and they settled into his apartment on 72nd Street. However, his writing activity had all but ceased by that time. Brown had hyper-thyroid issues, with an overactive gland that soon manifested itself into a goiter around his neck. Beginning in the late winter of 1924 he went in for a series of surgeries at the Manhattan Hospital to address this major health issue. It became the unfortunate focus of his life for much of 1924, curtailing his performing and songwriting activity completely. As the goiter took over his neck it slowly started to asphyxiate him. During a surgery on November 28, 1924, just two days before his 1st wedding anniversary with Ethel, Al lost his battle with the disease. Variety of December 10, 1924, noted that he was one of four "Tin Pan Alley" songwriting lights lost in a ten-day period, including Tommy Gray, Bobby Jones, and the dynamic New York March King E.T. Paull. He was cremated and his memory faded into the place where many of the blue collar variety of Broadway songwriters went. Even at that, one of his shows, the aptly-named What Next, had a tour in the summer of 1926. Al W. Brown may be less remembered in the 21st century, but for his fine melodies and hard behind-the-scenes work, he still deserves a spot as one of the shining lights of the "Great White Way," as well as his Chicago musical heritage.

The bulk of the information found on Brown came from government records, sheet music covers, and a wealth of newspaper accounts. Just the same, more light could be shed on his earlier years of the 1890s, including confirmation or lack thereof of his role in Song of the Type Writer Girl. Any such additional information would be both welcomed and acknowledged in this essay. Just click on my head on the main page of the site to send an email.