The tale of Miss Billie Brown starts out as one full of incredible promise, but sadly ends with her evident potential cut short by mortality. Yet even after she was gone she managed to have some impact in the world of recorded music, crossing race lines and transcending age and the ages. Some of the mystery of who she really was will be revealed here.

It should first be noted throughout all the research the author has done on over 500 women composers of the ragtime era and beyond that nearly half of them seemed to age less than ten years in at least one or two decades of their life, sometimes as little as a remarkable three years per ten. There are ways to see around this decision of vanity to find their actual age, which makes a difference when discussing when they first started composing. However, in the case of Miss Brown, or perhaps her mother, this exaggeration was not only extreme but started at a markedly early age, perpetuating a myth that has fooled many researchers, including this author. Thanks to some information sent by researcher Nora Hulse, a better accounting of Miss Brown's overall life can be assembled. Billie and her mother even fooled the State of Missouri, claiming on her death certificate that she was but eighteen and born in 1903, leaving off up to possibly nine years. Now, here is something more like the truth.

Billie was born as Irene Anderson in or near Eureka Springs, Arkansas, in 1894 (possibly 1895) to Swedish father Charles Anderson and either Illinois or Arkansas-born mother Edith P. "Eddie" Welker. Edith died at some point prior to 1900, and although Irene showed as living with Charles and his new wife Maud in Chicago for the 1900 census, that may have been a placeholder reference as she was concurrently listed, same birth month but one year off, as living in Eureka Springs with William B. Brown of Ohio and Anna Welker of Kansas, a childless couple who had been married since 1886. As of that enumeration, William was listed as a saloon owner [scribbled in over the word "carpenter" which is crossed out], and Irene was specifically noted as their "adopted daughter". Given that earlier census records are typically more accurate, and that the 1900 census specifically had both month and year included, 1894 is the most likely year of birth, far from the 1903 year given on her death certificate.

a childless couple who had been married since 1886. As of that enumeration, William was listed as a saloon owner [scribbled in over the word "carpenter" which is crossed out], and Irene was specifically noted as their "adopted daughter". Given that earlier census records are typically more accurate, and that the 1900 census specifically had both month and year included, 1894 is the most likely year of birth, far from the 1903 year given on her death certificate.

a childless couple who had been married since 1886. As of that enumeration, William was listed as a saloon owner [scribbled in over the word "carpenter" which is crossed out], and Irene was specifically noted as their "adopted daughter". Given that earlier census records are typically more accurate, and that the 1900 census specifically had both month and year included, 1894 is the most likely year of birth, far from the 1903 year given on her death certificate.

a childless couple who had been married since 1886. As of that enumeration, William was listed as a saloon owner [scribbled in over the word "carpenter" which is crossed out], and Irene was specifically noted as their "adopted daughter". Given that earlier census records are typically more accurate, and that the 1900 census specifically had both month and year included, 1894 is the most likely year of birth, far from the 1903 year given on her death certificate.As for the relationship between Edith and Anna, they were evidently cousins rather than sisters, both residents of Carroll County, Arkansas, in the early 1890s, each having been married there. Charles was shown in subsequent enumerations with Maud and daughter Clarice, born in 1899, in Illinois, with no trace of Irene, giving the identification of the correct parents and the adoption by the Browns more credence. No definitive death record was found for Edith Welker, but it is implied in a family tree as before 1900.

Little is known of Irene’s earliest years, but they likely included some musical exposure owing to her exposure to her adoptive father’s saloon. Little is known of her earliest years, but they likely included some musical exposure owing to the saloon business. In addition to that, William was the mayor of Eureka Springs during part of the decade, apparently from 1901 to 1903, and a member of the Odd Fellows, which implied that he was relatively well off for the area. This speaks to the ability to afford private piano lessons, which seems likely, given her talent as it later blossomed. An August 29, 1905 notice in the Daily [Little Rock] Arkansas Gazette reporting on an incident in Eureka Springs noted that:

James Castineau, ex-policeman was today held in seven hundred and fifty dollars bail to await the action of the grand jury, charged with attempt to assault Irene Anderson, ten years old, adopted daughter of ex-Mayor W.B. Brown. Feeling against Castineau is strong.

As of the April 1910 census the family was still living in Eureka Springs, and William still owned a saloon, but Irene was now referred to as Willie Anderson, perhaps after her adoptive father, or a hint as to her middle name. Her age, which should have been 15, was noted as 14, implying an 1895 birth year (the census was taken in April two months before her birthday).

It is clear that the Brown's adopted daughter showed extraordinary musical talent at the piano even before her teens, and Billie either had some public school training or, more likely, some private tutelage for both piano performance and harmony and theory. This was the case for other composers who similarly were in such an environment, where visiting pianists might teach them a thing or two before they left town. Sadly, disharmony entered the household, and Anna appears to have left William, moving to Kansas City with Willie as early as 1911, based on a possible listing found in that year's city directory, and no later than 1913.

Mother and daughter surfaced in 1915 at Libbie Dwyer's Rooming house on Locust Street on the Missouri side of Kansas City. Anna's daughter was now referred to as Billie Brown, modifying her first name again and changing her birth last name. Her heart was clearly in music, and she started in the trade at a fairly young age (until recently thought perhaps to be in her early teens), even garnering a mention at age 20 or 21 in the Music Trade Review of October 30, 1915:

DEVELOPING MUSIC BUSINESS.

Two Kansas City Women Who Are Doing Well with the Century and McKinley Lines.

Two Kansas City Women Who Are Doing Well with the Century and McKinley Lines.

The Owl's Nest Music Shop, operated by Miss Lenore Rudd and Miss Billie Brown, is installing a cabinet for its teachers' musical literature. The young women have been handling the Century Edition, having a complete line, and they have the past week received the McKinley Edition. They are fully equipped for teachers, and also they are building a good reputation for always having everything anybody wants in the sheet music line.

Miss Rudd was for several years manager of the sheet music department of the Jones Store Co., and previous to that had been with other sheet music departments. Miss Brown was Miss Rudd's assistant at the Jones Store.

It was implied in that mention that even before this time that Billie had gone to work to help support herself and her mother, as well as nurture her talent. Owl Music, where she spent some years, was actually the small music department of the Owl Drug Store. That same year, as noted in the city directory, she also went to work as a pianist playing for diners at the Finance Cafeteria, which was situated in the basement of the Finance Building in downtown Kansas City.

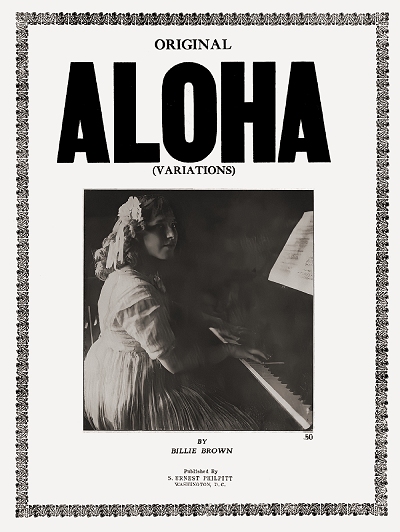

It was also in 1915 that one of the first two publications with Billie's name on them appeared. One was a simple set of variations of the increasingly popular Aloha Oe by Queen Lili'uokalani of Hawai'i. The other one was an arrangement of the song Shower of Kisses, which was composed by her mother. It was mentioned in a 1915 publication and advertised on the back cover of Aloha Oe, but copyrighted in 1916. Both were published by the store as the Owl's Nest Publishing Company, jobbed out as a vanity printing in Kansas City. The cover of Aloha Oe has a picture of what is likely Billie dressed down to look much younger than her probable age of 21 at that time.

No other music has been found from 1916 or 1917. Anna was still living on Locust Street during that period, and in the 1916 city directory she also listed music as her occupation. It appears that Billie was living elsewhere at the time of that listing, further supporting the 1894 birth date. In 1918 both of them were paired up again at 1214 Cherry Street. That year mother and daughter published another piece through the Owl Music Shop, The Star and the Rose. It garnered enough attention that the piece was picked up the following year by composer and publisher Fred Heltman of Cincinnati, Ohio, who enhanced and rearranged the piece with a violin obligato, adding his name to the composer credit, and thus increasing Miss Brown's credibility at age 25, even though an age closer to 16 or 17 was being claimed. In the 1919 directory both were back at 1009 Locust Street.

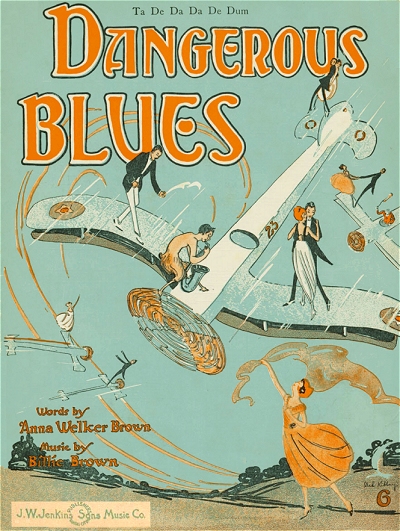

Billie appears to have continued to write and play throughout the next couple of years, and had a number of pieces that she reportedly had tried to get published elsewhere, but with little success. Around 1920 when the Owl Music Store went out of business she went to work for J.W. Jenkin's Sons Music, the largest in Kansas City, Missouri. She appeared as their employee in the 1921 city directory. At some point her employer recognized her obvious writing talent, and in 1921 took on Billie's Dangerous Blues (Ta De Da Da De Dum), with lyrics by her mother, Anna Welker Brown. The near-immediate success of this publication signaled the start of a career as a composer, and perhaps performer, and garnered Billie nationwide attention in the trade, and across color lines. Dangerous Blues was arranged for popular bands, and was recorded by The Original Dixieland Jazz Band (6/7/1921), black blues singer Mamie Smith (5/20/1921), and black pianist/composer Eubie Blake. The piece quickly went into a second printing, and there was the promise of much more on the way.

The piece quickly went into a second printing, and there was the promise of much more on the way.

The piece quickly went into a second printing, and there was the promise of much more on the way.

The piece quickly went into a second printing, and there was the promise of much more on the way.Then suddenly it was tragically over in early December, as Billie contracted the deadly disease smallpox and died on December 4. December 24 has been erroneously reported, but the death certificate is clear on the date. It is also clear on a 1903 year of birth, which is part of the reason researchers considered her to be much younger than her actual 26 or 27 years. This was exacerbated by the report of her passing in the Music Trade Review of January 14, 1922:

DEATH OF BILLIE BROWN REGRETTED

Youthful Composer a Victim of Smallpox Epidemic in Kansas City

Youthful Composer a Victim of Smallpox Epidemic in Kansas City

The composer of "Dangerous Blues" is dead. "It does not seem possible to us here in the office where she came from day to day and brought her cheerfulness and happy heart," said E. G. Ege, manager of the music publishing department of the J. W. Jenkins' Sons Music Co., of Kansas City, "but she is gone."

Billie Brown was scarcely eighteen [sic] years old, and had just entered upon what promised a brilliant career as a composer of popular music. She was identified with the retail store of J. W. Jenkins' Sons Music Co., and demonstrated in the piano department, and had from a child composed little things which she played on occasion. She sent her "Dangerous Blues" to a dozen music publishers, only to have it returned. She came to the Jenkins store and asked for a position of some sort to help her support herself and her mother, and was employed to play the piano. One day she was playing "Dangerous Blues" and Mr. Ege, attracted by its unusual character, stopped and asked her what was the name of the piece. She told him, and the conversation following resulted in the company paying her $100 for the composition.

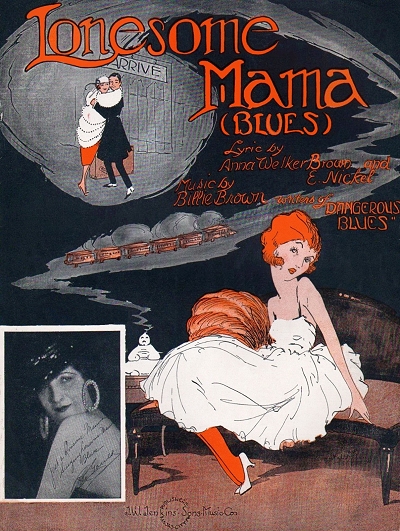

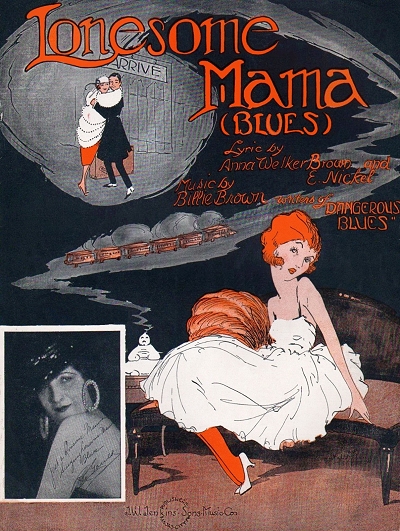

"Dangerous Blues" was first published in the Spring of 1921 and was an instant success, more than a million copies having been sold. By the first of July the sales had grown to such proportions that the Jenkins firm felt that they were justified in changing the contract with Billie Brown and of paying her a royalty instead. They therefore handed her a check for $500 and told her to write more songs. Two of these will be released in January, one of them, "Lonesome Mama Blues," appearing on the 1st, and the other, "Lullaby Moon," on the 15th. There are some others to follow later which the brilliant little composer had finished before her untimely death last week from smallpox.

True to their word, Jenkins released the other two blues. Lonesome Mama Blues got some traction and was recorded as well. Lullaby Moon was a lovely ballad that demonstrated Billie's versatility as a writer. However, her most outstanding legacy was clearly Dangerous Blues, especially as represented in the recording by black blues singer Bessie Smith who made the piece sound like it was from the pen of a seasoned composer of her own race, not a teen-aged white girl.

In the 1922 Kansas City directory, Anna Brown, now living at 620 E. 9th, listed herself as a music writer. As it was, one other song co-composed with her late daughter was released in 1924. Even though Anna was still around in the early 1930s, William Brown considered himself as widowed in the 1930 census taken in Eureka Springs. This may have been the result of the pain from losing his adopted daughter. Fortunately, she has not been lost to history, her one iconic piece is still performed over a century later, keeping the name and memory of Billie Brown alive.

Thanks to the late historian Nora Hulse for sending along information that helped to make this account of Miss Brown's life much more accurate than previously published, as well as information on William Brown's stint as mayor from ragtime era researcher Reginald Pitts. The author has confirmed these findings and augmented them with further research. The contention of Billie being the adopted daughter of the Browns is based on circumstantial evidence and the 1900 census. It is very probable that no official adoption record was filed in rural Arkansas as laws were not uniform and rather lax at that time outside of larger municipalities. However, the recognition of school systems and the government that Irene/Billie was their adopted daughter acts as a proxy to support the intent of adoption as a likely fact. The mention in the Arkansas Gazette of 8/29/1905 further reinforces this likelihood. While questions continue to be raised about her actual age, it makes little sense that a 12-year-old would be working in a music store rather than going to school, and less that she had prior experience working for the store manager, and even less that she would warrant a directory listing at an address other than her mother's. So it is fairly evident that the contention that Billie Brown was 18 when she died is false, likely part of a facade being kept up by Anna Welker and others close to the girl. The author is highly confident of the content of this article relating to Billie Brown and her time line.

Compositions

Compositions