From 1910 forward, when she first came into the public eye, Blanche L. Merrill, the better known of the two Blanche Merrills of New York, was very evasive about personal details, photographs, and more. It may have been more than just privacy, as part of what she was presenting was publicity as well, working in her favor, even if it was not all true. Not all of the answers to Blanche's past were found, but enough pieces were uncovered to at least unravel some of it. And a more recent 2021 visit into her early years coming from a different angle revealed much more than the last iteration of this biography, triangulating through a variety of records that filled in the picture, while still leaving a few questions unanswered.

The traditional birthdate given for Blanche, July 23, 1895, which is part of her official ASCAP biography, can be readily called into question. Her Social Security Administration death record as well as a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania birth listing from hospital records pose the first challenge, both giving a more precise birth date of July 22, 1883, considerably earlier by a dozen years and a day. For this essay, assuming the probability that Blanche was trimming several years off her age, perhaps for novelty and notoriety, the birth date will be assumed not as July 23, but July 22, 1883 as per her official birth and death records.

Blanche was born to Sigmund A. Dreyfoos (sometimes seen as variations Dreyfoose and Dreyfuss), an Ohio native of Germanic parents, and Catherine Elizabeth "Lizzie" Murphy, a New York native of Irish immigrants.  Among her seven siblings were Nellie (1877-11/8/1893), Teresa "Tessie" (11/25/1878), Clara (2/15/1881), and William Wallace (4/6/1888). According to his WWI draft record, Wallace had infantile paralysis which made him a paraplegic in his youth. Three other siblings, died in infancy or childhood. The 1892 New York State census taken in Long Island City in Queens, where the family had moved before Wallace was born, showed Sigmund to be in the liquor business, possibly an importer or dealer. Nellie died in late 1893, and Sigmund would pass in January 1899, leaving Elizabeth a widow. The 1900 enumeration showed her and the four remaining children residing with Elizabeth's widowed sister Margaret in Queens, with Teresa working as a schoolteacher. References to an alumni association for Bryant High School in Queens indicate that Blanche was part of the class of 1902, graduating shortly before she was age 19.

Among her seven siblings were Nellie (1877-11/8/1893), Teresa "Tessie" (11/25/1878), Clara (2/15/1881), and William Wallace (4/6/1888). According to his WWI draft record, Wallace had infantile paralysis which made him a paraplegic in his youth. Three other siblings, died in infancy or childhood. The 1892 New York State census taken in Long Island City in Queens, where the family had moved before Wallace was born, showed Sigmund to be in the liquor business, possibly an importer or dealer. Nellie died in late 1893, and Sigmund would pass in January 1899, leaving Elizabeth a widow. The 1900 enumeration showed her and the four remaining children residing with Elizabeth's widowed sister Margaret in Queens, with Teresa working as a schoolteacher. References to an alumni association for Bryant High School in Queens indicate that Blanche was part of the class of 1902, graduating shortly before she was age 19.

Among her seven siblings were Nellie (1877-11/8/1893), Teresa "Tessie" (11/25/1878), Clara (2/15/1881), and William Wallace (4/6/1888). According to his WWI draft record, Wallace had infantile paralysis which made him a paraplegic in his youth. Three other siblings, died in infancy or childhood. The 1892 New York State census taken in Long Island City in Queens, where the family had moved before Wallace was born, showed Sigmund to be in the liquor business, possibly an importer or dealer. Nellie died in late 1893, and Sigmund would pass in January 1899, leaving Elizabeth a widow. The 1900 enumeration showed her and the four remaining children residing with Elizabeth's widowed sister Margaret in Queens, with Teresa working as a schoolteacher. References to an alumni association for Bryant High School in Queens indicate that Blanche was part of the class of 1902, graduating shortly before she was age 19.

Among her seven siblings were Nellie (1877-11/8/1893), Teresa "Tessie" (11/25/1878), Clara (2/15/1881), and William Wallace (4/6/1888). According to his WWI draft record, Wallace had infantile paralysis which made him a paraplegic in his youth. Three other siblings, died in infancy or childhood. The 1892 New York State census taken in Long Island City in Queens, where the family had moved before Wallace was born, showed Sigmund to be in the liquor business, possibly an importer or dealer. Nellie died in late 1893, and Sigmund would pass in January 1899, leaving Elizabeth a widow. The 1900 enumeration showed her and the four remaining children residing with Elizabeth's widowed sister Margaret in Queens, with Teresa working as a schoolteacher. References to an alumni association for Bryant High School in Queens indicate that Blanche was part of the class of 1902, graduating shortly before she was age 19.There appears to have been some notion as she was approaching 19 that Blanche wanted to go into show business, at least on a small scale. There are mentions of her in local papers such as The Greenpoint [Brooklyn] Daily Star as performing in small-scale shows and events, including one from February 8, 1902, where she performed a solo in a Long Island City High School Association show, and two from March 7 and March 15, 1902, where she sang Our Favorite for the Robert Burns Society at Hettinger's Broadway Hall in Astoria. Blanche also participated in shows for Saint Mary's Catholic Club on Fifth Street, including The Woman Hater in 1905, and The Jolly Bachelors in 1906, both reviewed in the Daily Star. The review of the latter stated that "... [others] and Blanche Dreyfoos managed to take one step higher in the art with which they have been so generously endowed." Blanche's sister Clara participated in the shows as well.

Despite these forays into local theater, before or during 1906, 22-year-old Blanche went to the teacher training school at Columbia University in New York City in order to obtain a public school teaching certificate. While at least one interviewer claims she went to Barnard College, the former is more likely given family finances and proximity. However, her life interests lay in a different direction. Through various local productions in Queens and Brooklyn, Blanche's name, still as Dreyfoos, became known to a couple of performers as somebody who had a knack for writing and delivering comedy, and comic songs in particular. Mentions of her in the reviews of the shows helped her stand out to some certain readers and their friends.

While at least one interviewer claims she went to Barnard College, the former is more likely given family finances and proximity. However, her life interests lay in a different direction. Through various local productions in Queens and Brooklyn, Blanche's name, still as Dreyfoos, became known to a couple of performers as somebody who had a knack for writing and delivering comedy, and comic songs in particular. Mentions of her in the reviews of the shows helped her stand out to some certain readers and their friends.

While at least one interviewer claims she went to Barnard College, the former is more likely given family finances and proximity. However, her life interests lay in a different direction. Through various local productions in Queens and Brooklyn, Blanche's name, still as Dreyfoos, became known to a couple of performers as somebody who had a knack for writing and delivering comedy, and comic songs in particular. Mentions of her in the reviews of the shows helped her stand out to some certain readers and their friends.

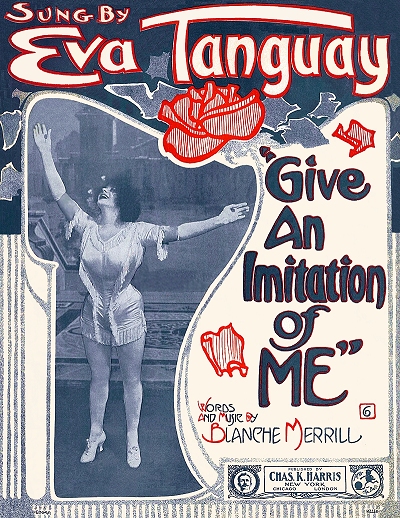

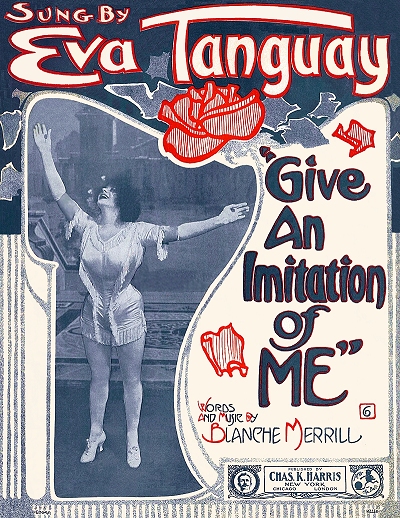

While at least one interviewer claims she went to Barnard College, the former is more likely given family finances and proximity. However, her life interests lay in a different direction. Through various local productions in Queens and Brooklyn, Blanche's name, still as Dreyfoos, became known to a couple of performers as somebody who had a knack for writing and delivering comedy, and comic songs in particular. Mentions of her in the reviews of the shows helped her stand out to some certain readers and their friends.The one with the most import was Eva Tanguay. Eva was otherwise known as the "I don't care" girl for her singing of that particular song of the same name, as well as her general attitude. Having attended theatrical performances regularly since her late teens, Blanche was taken by the singer at a 1910 performance and reportedly wrote Give an Imitation of Me for her, then filing it away after having second thoughts. She was finally convinced to submit the number to Miss Tanguay who took a liking to it and the author. Eva was not so surreptitious about her stage sexuality and titillation, and in Blanche she found somebody who could cleverly present her with songs that were both entertaining and unlikely to cause too much trouble. This from a woman who came out on the stage wearing nothing but a scanty outfit made of dollar bills. The formal introduction of Blanche L. Merrill (the origin of that nom de plume is still a mystery) to the music world was published in the Music Trade Review of July 16, 1910, although the age reference has been determined to be a bit off:

YOUNG WOMAN WRITES TANGUAY SONGS.

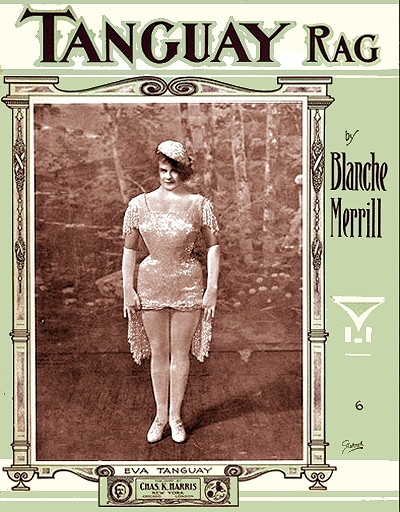

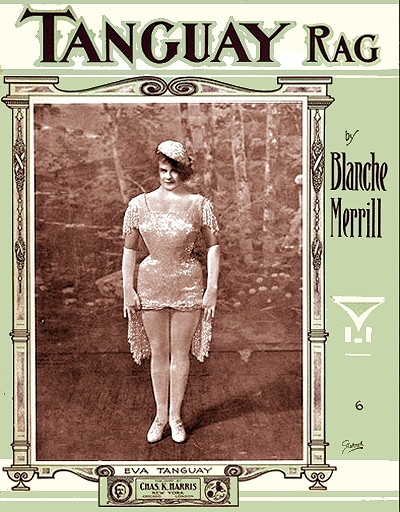

In addition to her numerous accomplishments, already recognized, please add one more to the genius of Eva Tanguay, says Joshua Lowe in the Morning Telegraph. What may be described as an Eva Tanguay "find" is a young woman, still in her teens, the daughter of a prominent family living in the wilds of Long Island, who bids fair to shine as one of the country's foremost lyric writers and popular composers. Her name is Blanche Merrill and she is so modest that she refuses to sit for a photograph or to supply me with any details of herself. All that I can learn is that in some mysterious way she was discovered by Miss Tanguay and that the "I Don't Care" comedienne employed her to write "The Tanguay Rag," "Give An Imitation of Me," "Egotistical Eva," "I Can't Help It," "Whistle and Help Me Along," and several other attractive ditties to be exclusively used by Miss Tanguay.

Indeed, Blanche's first known published pieces were the ones described in the article, issued by Charles K. Harris in New York. There are some indications that she may not have accepted payment for her first one or two pieces, but this is difficult to confirm. The Tanguay Rag in particular had a short burst of success in Eva's act. However, all of the sequestration and keeping certain details from the press were possibly a ploy to not only keep Merrill a bit closer to Tanguay at the time, but to get even more publicity for having a supposedly teen-aged writer in her camp. She was also cautious in the beginning in trusting songwriting as a viable income. The 1910 census taken in Queens showed that Blanche and her three siblings were still residing with their mother in Queens, with Eva listed as a public-school teacher, sharing that occupation with both Clara and Theresa.

However, all of the sequestration and keeping certain details from the press were possibly a ploy to not only keep Merrill a bit closer to Tanguay at the time, but to get even more publicity for having a supposedly teen-aged writer in her camp. She was also cautious in the beginning in trusting songwriting as a viable income. The 1910 census taken in Queens showed that Blanche and her three siblings were still residing with their mother in Queens, with Eva listed as a public-school teacher, sharing that occupation with both Clara and Theresa.

However, all of the sequestration and keeping certain details from the press were possibly a ploy to not only keep Merrill a bit closer to Tanguay at the time, but to get even more publicity for having a supposedly teen-aged writer in her camp. She was also cautious in the beginning in trusting songwriting as a viable income. The 1910 census taken in Queens showed that Blanche and her three siblings were still residing with their mother in Queens, with Eva listed as a public-school teacher, sharing that occupation with both Clara and Theresa.

However, all of the sequestration and keeping certain details from the press were possibly a ploy to not only keep Merrill a bit closer to Tanguay at the time, but to get even more publicity for having a supposedly teen-aged writer in her camp. She was also cautious in the beginning in trusting songwriting as a viable income. The 1910 census taken in Queens showed that Blanche and her three siblings were still residing with their mother in Queens, with Eva listed as a public-school teacher, sharing that occupation with both Clara and Theresa.Even though Blanche was later known largely as a lyric writer, she wrote the music for a number of her pieces, including these first few. After some minor successes in 1911 she was teamed up with Leo Edwards, allowing Blanche to focus on her clever lyrics while he provided appropriate music. After a collaboration that they had published by Leo Feist, Charles Harris took action, hiring Edwards as a staff composer to work specifically with Blanche, who by now was part of the staff, and to be available for other lyricists in the Harris fold.

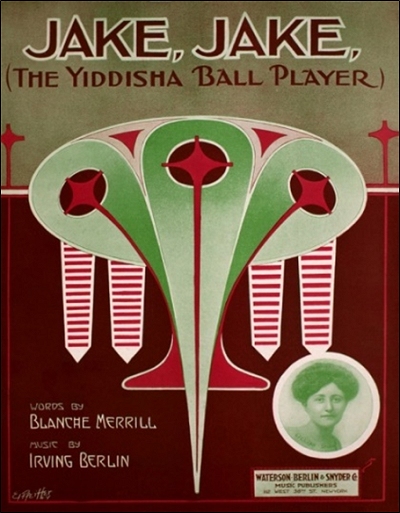

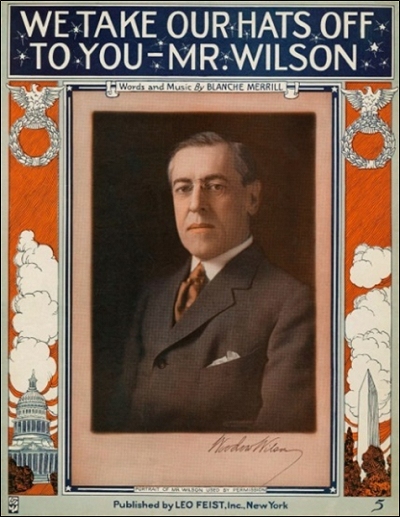

Merrill and Edwards songs made the rounds on Broadway as well as the vaudeville stage, and by 1913 the team was well known for their clever ditties. In 1914 Blanche wrote some material with no less than another rising star, Irving Berlin. Jake, Jake, the Yiddisha Ball Player did quite well as a comic number on the New York stages. Her song We Take Our Hats Off to you, Mr. Wilson, saluting the current president, was also a hit. By the time 1915 came around Blanche was also trying her hand at writing short vaudeville acts, including The Burglar, which was advertised as having been performed by Maurice Burkhardt, according to the Daily Standard Union. Another, The Musical Devil, performed by an actress named Yvette Rubel, known as "the Miniature Prima Donna." One rising star who took a keen interest in the acts, the Wilson song, and Blanche in particular, was a woman recently employed by Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., for his famous Follies. Her name was Fanny Brice, and she would further propel Blanche to behind-the-scenes stardom while the writer did the same for the effervescent Brice in return.

In a 1925 interview published in the Saturday Evening Post, Brice noted how Merrill had already been pegged as an adaptable writer who was able to custom fit material to nearly any actress' stage persona. Among those listed in addition to Tanguay were Stella Mayhew, Rita Bolan, Lillian Shaw and Rae Samuels. Her material was also expanded into entire sketches for some of these performers, and by the mid-1910s copyrights started appearing for the acts as well, written by or co-written with Blanche.

Among those listed in addition to Tanguay were Stella Mayhew, Rita Bolan, Lillian Shaw and Rae Samuels. Her material was also expanded into entire sketches for some of these performers, and by the mid-1910s copyrights started appearing for the acts as well, written by or co-written with Blanche.

Among those listed in addition to Tanguay were Stella Mayhew, Rita Bolan, Lillian Shaw and Rae Samuels. Her material was also expanded into entire sketches for some of these performers, and by the mid-1910s copyrights started appearing for the acts as well, written by or co-written with Blanche.

Among those listed in addition to Tanguay were Stella Mayhew, Rita Bolan, Lillian Shaw and Rae Samuels. Her material was also expanded into entire sketches for some of these performers, and by the mid-1910s copyrights started appearing for the acts as well, written by or co-written with Blanche.Brice engaged Merrill to write some custom material for a September 6, 1915 performance at the Palace Theater, then later for the next edition of the Ziegfeld Follies act after a failed showing in February of that year. The reviews of the Palace engagement performances in September and then February 1916 clearly spoke volumes about a new hitch in Brice's step on stage, and a character rendition that fit her perfectly. The material that Blanche worked up for Fanny, and continued to provide for the next few years, helped the actress to develop her Sadie Salomé character and wry stage wit. It was a two-way street that built up both the reputations and bank accounts of each of them. Curiously, the 1915 New York State census showed Blanche still living with her mother (listed as Catherine) and older sisters, still shown as schoolteachers. All three daughters dropped their ages by several years, showing themselves as younger than their brother Wallace, who had become an attorney.

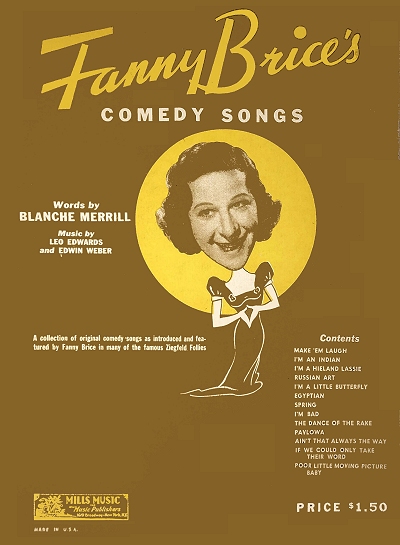

No matter the composer, and there were select others besides Leo, it was Blanche's lyrics and Fanny's delivery that sold the songs, literally, since the sheet music was often available in the lobby after the show. Some of the pieces, however, appear to have been kept out of publication and in Brice's exclusive domain, not showing up in print until a 1939 compilation of her songs with lyrics by Blanche was released. One of her favorites, which was alluded to in the Brice biographical stage musical Funny Girl, was The Dying Swan, performed with her characteristic Yiddish humor. Somehow, Blanche made a connection with Fanny's ethnic side that created a palpable chemistry when carefully assembled. A good example of this was I'm An Indian (a variation on The Yiddish Indian) written for Why Worry in 1918. While the play did not last long, Fanny's version of and love for the piece endured, ending up in her iconic 1928 short film My Man, then again in abbreviated form in the 1945 MGM film Ziegfeld Follies.

By the early 1920s the relationship between Fanny and Blanche had cooled, but the reasons may be somewhat complicated. It was reported that Merrill had a rather loud difference of opinion with Ziegfeld on what her role in the Follies of 1919 (largely composed by Irving Berlin) should be, and she was summarily dismissed by the boss. It is also probable that Fanny's contract with Ziegfeld, a savvy negotiator, prohibited her from working with songwriters outside of the organization while under his employ. Fanny enjoyed being employed, and likely complied for that reason.

and she was summarily dismissed by the boss. It is also probable that Fanny's contract with Ziegfeld, a savvy negotiator, prohibited her from working with songwriters outside of the organization while under his employ. Fanny enjoyed being employed, and likely complied for that reason.

and she was summarily dismissed by the boss. It is also probable that Fanny's contract with Ziegfeld, a savvy negotiator, prohibited her from working with songwriters outside of the organization while under his employ. Fanny enjoyed being employed, and likely complied for that reason.

and she was summarily dismissed by the boss. It is also probable that Fanny's contract with Ziegfeld, a savvy negotiator, prohibited her from working with songwriters outside of the organization while under his employ. Fanny enjoyed being employed, and likely complied for that reason.Outside of her work with Brice, Blanche had again collaborated with Irving Berlin for the moderate hit show Dance and Grow Thin in 1917, which debuted at the Cocoanut Grove on the roof of Ziegfeld's Century Theatre. The firm of Waterson, Berlin and Snyder placed her under contract, partly to secure publishing and performance royalties from the production. While it was well-reviewed in the New York and trade papers, including several kind mentions of Merrill's contributions, a lot of the focus was on dancer Gertrude Hoffmann, who had made waves not too far back in her lascivious stage dance as Scheherazade, not disappointing here with a classy strip tease. That same year, Blanche was listed in the Manhattan directory under Dramatic Authors. The 1920 directory had a similar listing with an office at 1531 Broadway, and she listed herself as a writer for the census taken that January, still living in Queens with her mother and three siblings.

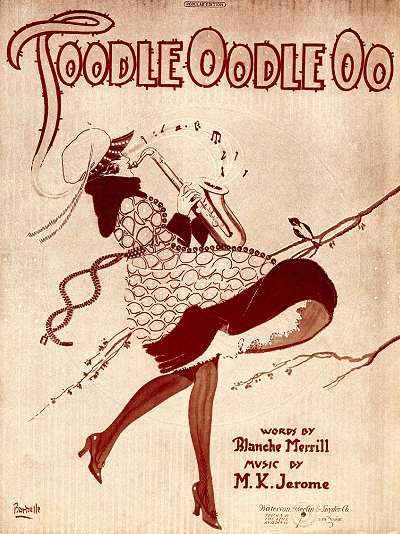

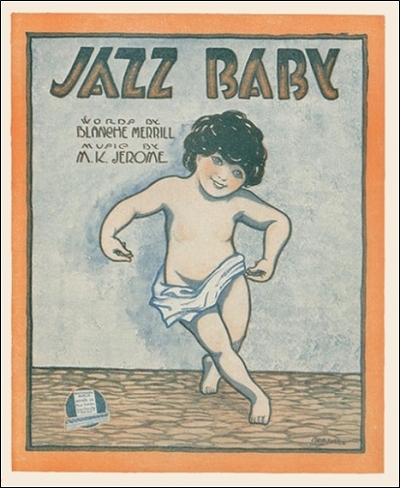

Another teaming from 1919 was working out pretty well. With composer Maurice K. Jerome, Blanche turned out a number of catchy songs in 1919, including one titled Jazz Baby. One of the first recordings was by James Reese Europe and his 369th U.S. Infantry Band in 1919. The tune caught on slowly, but it would not go away. In 1926 the rights were acquired by General Mills and the lyrics reworked, possibly by Jerome, to "Have You Tried," an advertisement for Wheaties cereal. This version was also loosely applied to the Wheaties-sponsored Abbot and Costello television show in the 1950s. Beyond that, Jazz Baby remained popular for decades, and was incorporated as a whole into the 1920s-themed movie Thoroughly Modern Millie in 1967. (It did not, however, survive the transition of the movie into a stage musical in 2004.)

Beyond that, Jazz Baby remained popular for decades, and was incorporated as a whole into the 1920s-themed movie Thoroughly Modern Millie in 1967. (It did not, however, survive the transition of the movie into a stage musical in 2004.)

Beyond that, Jazz Baby remained popular for decades, and was incorporated as a whole into the 1920s-themed movie Thoroughly Modern Millie in 1967. (It did not, however, survive the transition of the movie into a stage musical in 2004.)

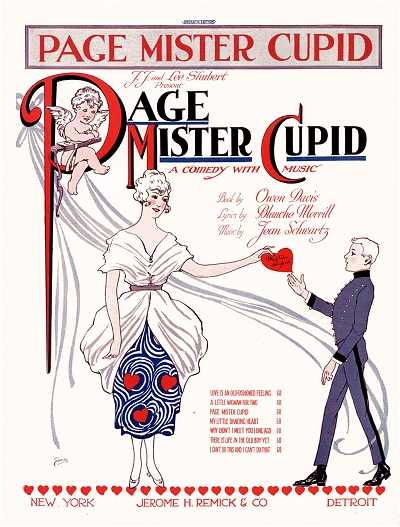

Beyond that, Jazz Baby remained popular for decades, and was incorporated as a whole into the 1920s-themed movie Thoroughly Modern Millie in 1967. (It did not, however, survive the transition of the movie into a stage musical in 2004.) Blanche moved on to work with the Shuberts in 1919, first composing works for the Shubert Gaieties of 1919. That same year she would team up with composer Jean Schwartz to rewrite a failed show titled Girls into a musical comedy, one she may have hoped to be her biggest hit of all, Page Mister Cupid. It did not turn out any stellar hit songs, and while the score was published, it apparently never made it to a full-fledged Broadway stage, closing out of town.

For many years, Merrill had been making a very healthy living with writing specialty songs for Brice and others, sometimes commanding prices in the low five figures, far more than Tin Pan Alley publishers were willing to invest. This made the songs for certain performers more or less proprietary. Consistent delivery of good content was essential in this regard. However, Blanche got in some trouble again when she failed to properly complete a musical comedy she had been contracted to complete, very possibly the failed Page Mister Cupid. Fanny and Blanche reunited in 1921 while Brice was between Follies appearances and created new custom material for vaudeville. Somehow, Fanny was able to gain permission to do Blanche's material in the 1923 edition of the Follies, and there was further collaboration in 1924 for the Music Box Revue.

In 1923 Blanche again made headlines for a rather remarkable gesture. She had met with noted actress Mollie Fuller who after a forty-year career had suffered more than half a decade of blindness. Blanche saw how disheartened Mollie was, not being able to perform any more, and wrote a play especially for her that would facilitate and actually utilize her condition in a positive way. Twilight, which was written in such a way as to mask Mollie's disability, renewed interest in the actress and was well received in its limited run. Fuller also spoke voluminously about her clever benefactor and the opportunity she had been given by Blanche to grace the stage one more time.

Blanche saw how disheartened Mollie was, not being able to perform any more, and wrote a play especially for her that would facilitate and actually utilize her condition in a positive way. Twilight, which was written in such a way as to mask Mollie's disability, renewed interest in the actress and was well received in its limited run. Fuller also spoke voluminously about her clever benefactor and the opportunity she had been given by Blanche to grace the stage one more time.

Blanche saw how disheartened Mollie was, not being able to perform any more, and wrote a play especially for her that would facilitate and actually utilize her condition in a positive way. Twilight, which was written in such a way as to mask Mollie's disability, renewed interest in the actress and was well received in its limited run. Fuller also spoke voluminously about her clever benefactor and the opportunity she had been given by Blanche to grace the stage one more time.

Blanche saw how disheartened Mollie was, not being able to perform any more, and wrote a play especially for her that would facilitate and actually utilize her condition in a positive way. Twilight, which was written in such a way as to mask Mollie's disability, renewed interest in the actress and was well received in its limited run. Fuller also spoke voluminously about her clever benefactor and the opportunity she had been given by Blanche to grace the stage one more time.In her 1925 interview for the Saturday Evening Post, Brice talked rather glowingly about Blanche and their decade-long collaboration, but by that time they had more or less finished with their relationship. Merrill herself made that point clear in a poem published in May 1925, in Variety, claiming that she was Fanny's "use [sic] to be writer," and now "the only one feeling blue," an indicator that it was likely Brice who ended things. But even the story behind that was complicated, as Fanny had recently lost her first true love, convicted gambler and securities thief Julius "Nicky" Arnstein, after which she had become involved with another songwriter lyricist, Billy Rose. Blanche had clearly met Rose as well, and had a rather low opinion of him as a human being. It may have been either personal animosity or professional jealously and exclusivity that caused Rose to have Fanny choose between them.

Even in the short years before sound came to film, Hollywood beckoned anybody they found with promise, and Blanche heard that call in 1925 when she was engaged by producer Joseph M. Schenck to go west and write scenarios (plot descriptions as opposed to a script with dialogue) for some of his projects. As relayed in Variety on December 19, 1925:

[Blanche] is now at work preparing a story for the Schenck unit and Mlss [Norma] Talmadge expects to begin work within a very short time on the well-known Belasco play [Kiki], while negotiations have been opened by Mr. Schenck to secure the screen rights of a current Broadway success for Constance Talmadge and the services of a famous director to do the picture.

Mr. Schenck's recent acquisition of famous stage writers for screen work given [sic] him what is recognized as one of the greatest staffs in Hollywood. Edward Clark, a playwright with a number of successful stage plays to his credit, has moved his family from New York and intends to make Hollywood bis permanent home. He and Miss Merrill were placed under contract as a result of the producer's recent visit to New York.

Blanche took a chance in doing this since her contract with Schenck (some would later would call him Skunk for his dealings) precluded her from writing for vaudeville during the trial period of six months. While in Hollywood during the first half of 1926, she was loaned out to other studios, including recently-founded MGM and Laskys' Famous Players, essentially working as a sort of dramaturg to improve some of their scenarios.

Near the end of the period, she was engaged to adapt a story for The Duncan Sisters, called Topsy and Eva. Blanche's take on it was ultimately rewritten by other participants, but some of the failure of the end product was deflected toward Blanche, and her Schenck contract ended, sending her packing.

|

Remaining in the west, Blanche started writing for various artists on the Orpheum Circuit, mostly for their theaters in Los Angeles and San Francisco, California. At the same time, she was still contributing sketches to New York area vaudeville acts, ostensibly either by mail or the occasional visit back East. She had a few successes during her time out West, but they were often diminished compared to what she had been realizing in prior years. Blanche copyrighted a handful of vaudeville sketches, but little in the way of songs for over a decade with American copyrights. In fact, other than writing, she all but disappeared from public view during this period. This was the peak time as a performer for the "other" Blanche Merrill, who was living in Newark, New Jersey, and playing with her own orchestra in Pleasant Valley, New York. There appears to have been little confusion during that time, but even Willie "The Lion" Smith, who had been married to the New Jersey Blanche Merrill, couldn't help but think every time he saw the name, wondering which Blanche it was until he caught the context.

Blanche's next big trip was to England, where she arrived in late 1929, just after the Wall Street crash. She was engaged by Walter Fehl and Murray Leslie to come up with material for them, including sketches and songs. She also wrote some for Dora Maugham, who was Fehl's wife. The end result was well-reviewed by British papers and perhaps put some pep in her step, as she was further engaged to write for other acts. She remained in London until October 1930 when she finally returned to New York City, just as the Great Depression was deepening and live shows were less well attended than the less expensive films from Hollywood. But vaudeville, in the beginning of its death throes, was not done yet, so there was still work to be had. Merrill did allow Rosetta Duncan, of the Duncan sisters for whom she had written in Hollywood, to utilize some of her earlier narrative songs in Rosetta's act in mid-1931, as well as some more material presented by Belle Baker, although it appears to have been earlier copyrighted works, not new material. Dora Maugham also came over from the UK and Merrill collaborated with her for some new material, as did prior clients Lillian Shaw and Irene Ricordo. Blanche herself was not a performer, at least once she started writing, so did not appear on stage. The few mentions of a Blanche Merrill playing in vaudeville were most likely of the pianist-bandleader and singer living in Newark.

In 1936 Blanche started renewing a number of her earlier copyrights, including a few pieces not published before. She was living in Jackson Heights, Borough of Queens, New York, at that time. According to columnist Walter Winchell, Merrill had spent some time and effort trying to gain admission to the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), but had been refused since 1933. It may have been Winchell's public comment that was enough of a bump for this prodigious writer to have her name added to the ASCAP roster in 1936, which even after the struggle was likely quite satisfying for her. It may not have hurt that Winchell also mentioned Blanche as being very ill at Roosevelt Hospital following an unspecified operation.

It may have been Winchell's public comment that was enough of a bump for this prodigious writer to have her name added to the ASCAP roster in 1936, which even after the struggle was likely quite satisfying for her. It may not have hurt that Winchell also mentioned Blanche as being very ill at Roosevelt Hospital following an unspecified operation.

It may have been Winchell's public comment that was enough of a bump for this prodigious writer to have her name added to the ASCAP roster in 1936, which even after the struggle was likely quite satisfying for her. It may not have hurt that Winchell also mentioned Blanche as being very ill at Roosevelt Hospital following an unspecified operation.

It may have been Winchell's public comment that was enough of a bump for this prodigious writer to have her name added to the ASCAP roster in 1936, which even after the struggle was likely quite satisfying for her. It may not have hurt that Winchell also mentioned Blanche as being very ill at Roosevelt Hospital following an unspecified operation.In the interim, as reported in the trades, Blanche had been sending scripts to radio stations in hopes of selling some. A few of them were accepted, but largely by some of her prior clients, such as the Duncan Sisters. Hoping to have a base from which to do business both in music and theater, she opened an office in associated with publisher Irving Mills of Mills Music. During that time, the biggest boon was the 1939 folio of Fanny's earlier songs published by Mills. Brice had become popular on radio, particularly playing her Baby Snooks character, which Merrill was not responsible for. However, that didn't stop the public from showing at least some interest in the earlier songs that defined Fanny during her years with the Ziegfeld Follies, and both Mills and Merrill benefited from taking a chance on the folio. There was also a mention of a musical titled Night Music which opened in New York in 1940, although it is not clear if Blanche's contributions to this show were new or recycled from earlier writing. The 1940 enumeration showed Blanche, using the last name of Dreyfoos, and her widowed sister Clara still residing in the Jackson Heights area of Queens, with Clara as a schoolteacher, and Blanche a writer of lyrics, claiming to be but 40, a mere 16 and a half years shy of her actual age of 56.

Over the next several years Blanche was engaged to write or modify material for Broadway revues, some for which she did not receive credit, so it is hard to pin down which shows she was involved in. A lot of activity was muted by World War II, which had taken precedence in the public eye, but Blanche still made small contributions here and there to stage and possibly radio. Once the war ended, she was engaged again by the Duncan Sisters to either recycle or write some new material for an act they staged in San Francisco in 1946. She copyrighted some of the unpublished works, not all of which may have been in the revue, in 1947. According to a Variety notice around the same time, Blanche was composing her autobiography in novel form and wholly in rhyme as if it were poetry or lyrics. However, traces of any publication, which was allegedly by Random House, were not found in our research, so it may never have come to fruition despite its reported completion. The 1950 census showed Blanche, again as Dreyfoos, residing in Queens with Clara, showing no occupation, and claiming to have never been married.

Even at age 67 in 1951, it turns out that Blanche was not done with her creative input into the expanding landscape of media. Several years prior she became known to Imogene Coca,

best remembered now for her association with Sid Caesar on Your Show of Shows in the early days of modern broadcast television. In a failed show from 1940 that she had been involved with writing, that starred, among others, Pert Kelton (Marians' mother in The Music Man on both stage and screen) and vaudevillian Joe Cook, whom she had undoubtedly crossed paths with before, Blanche had made an acquaintance with Coca that would come to fruition years later. In the interim, she had written some specialty numbers for Coca. In 1951, she was asked to step up to the plate once again and provide Coca with material for the earliest of the Your Show of Shows broadcasts on NBC television according to a notice in Variety in May 1951. Blanche initially agreed, but within a few months of taking the gig she seemed to have figured out what television was, and perhaps would be over the coming decades. By January of 1952 she had tired of the routine and demands of what she may have considered inane programming for television (given Sid Caesar's demeanor and humor, this may not have been far off the mark) and protested in a long poem sent to Variety in January 1952. Lamenting not only the similarities to radio and lack of originality or social importance as opposed to the message sponsors were trying to get across to the public, she cleverly, in her own way, eviscerated what would with the decade be referred to by Newton N. Minow of the FCC as "a vast wasteland." This obviously did not sit well with the network, but it remains unclear as to whether she quit before she was fired. Either way, Blanche was now retired at 68.

|

Beyond that, Blanche appears to have sadly faded into the woodwork and ridden into the sunset, living out her life in Jackson Heights with her sisters. She died there in late 1966 at age 83. Blanche had been preceded by Wallace in 1939 and Teresa in 1958, and was survived by Clara who passed in early 1971, the last of the Dreyfoos family. Some of her pieces, including Jazz Baby, have survived through performances into the 21st century, and much of the material she wrote probably lives in Old Time Radio broadcasts still extant in the digisphere. And then, there will always be Fanny Brice, and their intertwined fame and relationship. Blanche may never go away, but is that such a bad thing?

Compositions

Compositions