Charles B. Brown was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to German immigrant William Brown and his German bride Carbina Wilhelmina Buchs. His younger siblings included George (1872), Emma (1874), William (1876), Albert (1878), and Wilhelmina (1880). Although he later reported his birth year as 1870, the 1880 enumeration, taken in Kewaskum, Wisconsin, showed him to be eleven, so it was potentially 1869. The record also showed the senior Brown working for the railroad at a train depot. Milwaukee and surrounding areas had a heavy Germanic population by this time, which is, in part, how it became a center for breweries, as well as for fine music.

Milwaukee and surrounding areas had a heavy Germanic population by this time, which is, in part, how it became a center for breweries, as well as for fine music.

Milwaukee and surrounding areas had a heavy Germanic population by this time, which is, in part, how it became a center for breweries, as well as for fine music.

Milwaukee and surrounding areas had a heavy Germanic population by this time, which is, in part, how it became a center for breweries, as well as for fine music.Since so little information about Charles was left behind, and not published, nor even laid down in a family history, it is hard to determine the level of music education he received. However, it was certainly something beyond the usual public-school material, and he likely was given some private lessons in piano, at least one other instrument, and theory and harmony. By 1891 he had relocated south to Chicago, Illinois, and was working as an orchestra musician, and possibly an accompanist. Around 1892, Charles married his Pennsylvania-born wife Cora Thompson. The couple never had surviving children, although two were born and died in the mid-1890s.

When the craze for cakewalks started in 1897, Charles was pretty near to the front of the line in trying to get one into print. While they weren't quite ragtime, his first few pieces from 1898 and 1899 showed a grasp of what the coming music might be. Unfortunately, his titles and the cover images were steeped in the Negro stereotype that was common with so-called "coon" pieces of the era. But to the publishers, who made the decisions on how to market the pieces, this was just business as usual, and the questionable norm at that time. It was also an irony that so many "black" pieces came from the pens of while composers like Charles. Most of Brown's material was in the guise of marches, some with light syncopation and cakewalk rhythms, and given that the public in Chicago and elsewhere was secretly clamoring for this material that was being publicly scorned by classical musicians and clergy, he had little problem finding publishers to take the work. The 1900 census showed Charles and Cora in West Chicago, hosting one boarder, and with Charles listed as a working musician.

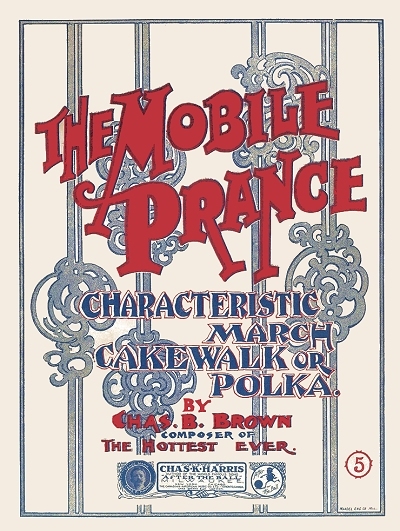

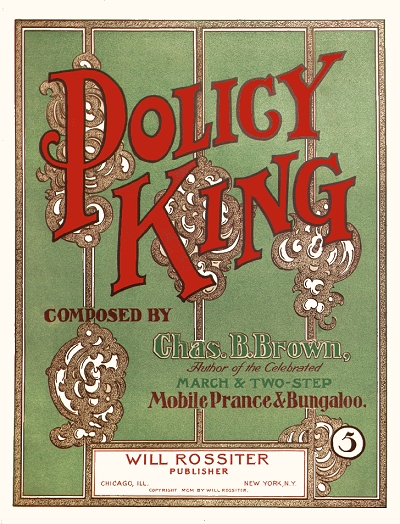

While he continued to work as an orchestra musician, Charles would compose something new now and then, but he was hardly prolific. After the moderately successful tune The Mobile Prance from 1901, he finally hit upon that one piece that other musicians and the public found catchy enough to make it into somewhat of a hit. Over the next decade and more, Policy King, first issued in 1905 by Will Rossiter, would find its way onto a number of piano rolls and recordings, including three of the latter between 1907 and 1917 by banjo player Vess L. Ossman. Charles would never find that measure of popularity with his later pieces, which included several waltzes and marches, but nothing with strong syncopation. Rossiter would reprint Policy King in 1907 shortly after Ossman's initial recording with a new cover, further spurring sales. The 1910 enumeration taken in Chicago confirmed that Brown was still working as an orchestra musician.

he finally hit upon that one piece that other musicians and the public found catchy enough to make it into somewhat of a hit. Over the next decade and more, Policy King, first issued in 1905 by Will Rossiter, would find its way onto a number of piano rolls and recordings, including three of the latter between 1907 and 1917 by banjo player Vess L. Ossman. Charles would never find that measure of popularity with his later pieces, which included several waltzes and marches, but nothing with strong syncopation. Rossiter would reprint Policy King in 1907 shortly after Ossman's initial recording with a new cover, further spurring sales. The 1910 enumeration taken in Chicago confirmed that Brown was still working as an orchestra musician.

he finally hit upon that one piece that other musicians and the public found catchy enough to make it into somewhat of a hit. Over the next decade and more, Policy King, first issued in 1905 by Will Rossiter, would find its way onto a number of piano rolls and recordings, including three of the latter between 1907 and 1917 by banjo player Vess L. Ossman. Charles would never find that measure of popularity with his later pieces, which included several waltzes and marches, but nothing with strong syncopation. Rossiter would reprint Policy King in 1907 shortly after Ossman's initial recording with a new cover, further spurring sales. The 1910 enumeration taken in Chicago confirmed that Brown was still working as an orchestra musician.

he finally hit upon that one piece that other musicians and the public found catchy enough to make it into somewhat of a hit. Over the next decade and more, Policy King, first issued in 1905 by Will Rossiter, would find its way onto a number of piano rolls and recordings, including three of the latter between 1907 and 1917 by banjo player Vess L. Ossman. Charles would never find that measure of popularity with his later pieces, which included several waltzes and marches, but nothing with strong syncopation. Rossiter would reprint Policy King in 1907 shortly after Ossman's initial recording with a new cover, further spurring sales. The 1910 enumeration taken in Chicago confirmed that Brown was still working as an orchestra musician.During the 1910s Charles issued a few more pieces overall than the prior decade, but they were once again more old school waltzes and marches, and nothing in the guise of ragtime or the latest dances. He took control of his work in the early 1910s, and started his own small publishing firm in Chicago. Perhaps a less capable notator or arranger, many of his pieces were arranged by some of his colleagues. Along the line he managed a couple of songs with well-known lyricists, including British immigrant Arthur J. Lamb, but nothing of significance. The 1920 census had Brown listed as a music publisher. His wife Cora passed on in September of 1924 at around age 58, and Charles died in late 1927 at age 58. His death record had him listed as a clerk. They were interred together at Waldheim Cemetery in Chicago.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions