Charles Spencer Chaplin (April 16, 1889 to December 25, 1977) | |||

Compositions Compositions | |||

|

(Note that many dates shown represent known or approximate composition dates rather than copyright, since some pieces associated with films were not published or copyrighted until some time after the film's release.)

| |||

Discography Discography | |||

|

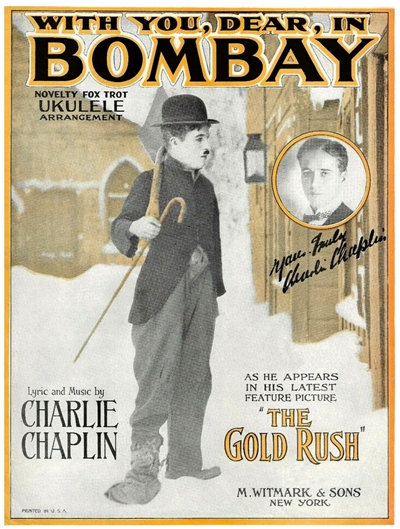

1925

With You, Dear, In Bombay [9]Sing a Song [9,10]

9. Conducting the Abe Lyman Orchestra

10. Vocal by Charles Kaley |

Matrix and Date

[Brunswick 15849/50] 05/??/1925[Brunswick 15872] 05/??/1925 | ||

Pieces About or Associated With Charlie Chaplin Pieces About or Associated With Charlie Chaplin | |||

|

1915

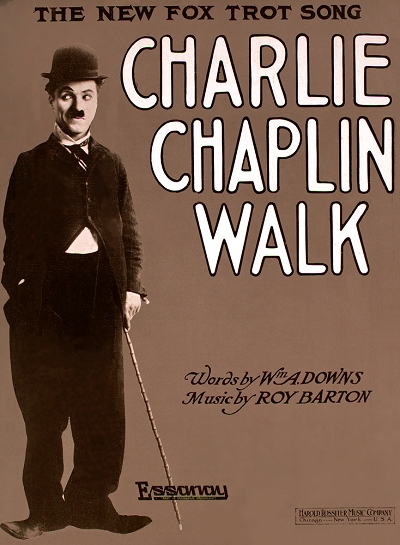

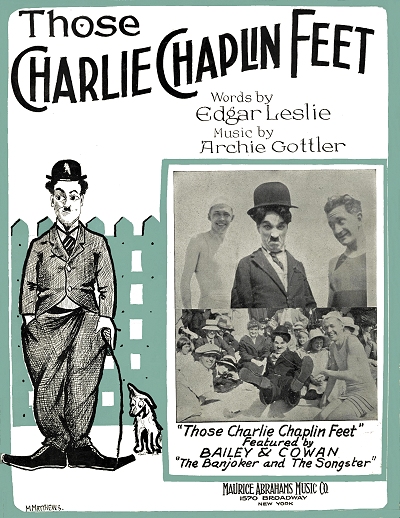

That Charlie Chaplin Walk [William S. Downs & Roy Barton]The Charlie Chaplin Glide [Gordon Strong] The Charlie Chaplin Trot [Gustave Leon] The Charlie Chaplin ["Pauline"] (c.1915) Those Charlie Chaplin Feet [Edgar Leslie & Archie Gottler] Funny Charlie Chaplin [James G. Ellis] Charlie Chaplin's Frolics: Eccentric Dance [Theodore Bonheur] Charlie! Charlie! [Herman Darewski & Dan Lipton] Broadway Is My Home Sweet Home [Meyer Davis, Uriel Davis & Donald M. McLeran] The Moon Shines Bright on Charlie Chaplin (Parody) [Unknown author - Melody of Red Wing by Kerry Mills] 1920

At the Moving Picture Ball [Howard Johnson & Joseph H. Santly]1921

The Kid (Introduced in 'The Kid') [Joe Bren & Haven Gillespie]Charlot (French Fox Trot) [Harold de Mozi, Henry Moreau & Jack Cazol] 1924

Mandalay [Earl Burtnett, & Abe Lyman]1939

Who is This Man (Who Looks Like Charlie Chaplin?) [Tommy Handley] | |||

Filmography Filmography | |||

|

Keystone Studios

1914

Making a LivingMabel's Strange Predicament Kid's Auto Race at Venice A Thief Catcher (Found 2010) Between Showers A Film Johnnie Tango Tangle (Charlie's Recreation) His Favorite Pastime Cruel, Cruel Love The Star Boarder (The Landlady's Pet) Mabel at the Wheel Twenty Minutes of Love [1] Caught in a Cabaret [1] Caught in the Rain [1] A Busy Day [1] The Fatal Mallet Her Friend the Bandit (Lost) [1] The Knockout Mabel's Busy Day Mabel's Married Life [1] Laughing Gas [1] The Property Man [1] The Face on the Barroom Floor [1] Recreation [1] The Masquerader [1] His New Profession [1] The Rounders [1] The New Janitor [1] Those Love Pangs (The Rival Mashers) [1] Dough and Dynamite [1] Gentlemen of Nerve [1] His Musical Career (The Musical Tramp) [1] His Trysting Places [1] Tillie's Punctured Romance [1] Getting Acquainted (A Fair Exchange) [1] His Prehistoric Past [1] Essanay Film Manufacturing Company

1915

His New JobA Night Out The Champion In the Park A Jitney Elopment The Tramp By the Sea Work A Woman The Bank His Regeneration (Cameo only) Shanghaied A Night in the Show Burleque on 'Carmen' 1916

PoliceLife (Unfinished -included in Triple Trouble) A Chaplin Snippet (Unknown Origin. Filmed at a February 1916 Benefit at the New York Hippodrome) 1918

Triple Trouble

1. Keystone Films Directed by Chaplin

All other non-Keystone Films Directed by Charles Chaplin |

Mutual Film Corporation

1916

The FloorwalkerThe Fireman The Vagabond One A.M. The Count The Pawnshop Behind the Screen The Rink 1917

Easy StreetThe Cure The Immigrant The Adventurer Chaplin Studios

1918

How to Make MoviesVarious Scenes with Harry Lauder Scenes shot with Visiting Celebrities First National

1918

A Dog's Life [2]The Bond Shoulder Arms [2] 1919

Sunnyside [2]1921

A Day's Pleasure [2]The Kid [2] The Idle Class [2] 1922

Pay Day [2]1923

The Pilgrim [2]United Artists

1923

A Woman of Paris [2]1925

The Gold Rush1928

The Circus [2,4]1931

City Lights [2]1936

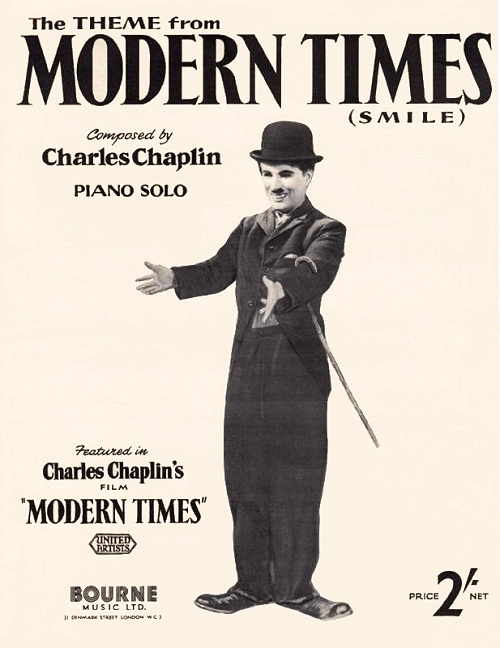

Modern Times [2]1940

The Great Dictator [2,3]1942

The Gold Rush [Redux] [2]1947

Monsieur Verdoux [2,3]1952

Limelight [2,4]1957

A King in New York [2]1959

The Chaplin Revue (Compilation) [2]1967

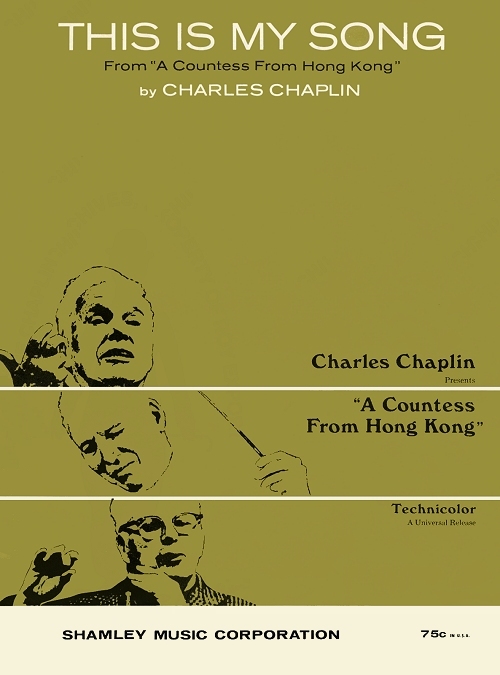

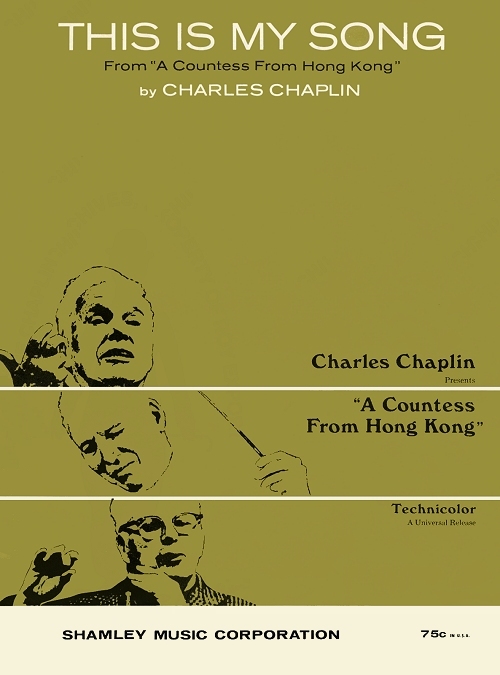

A Countess from Hong Kong [2]Roy Export Company

1975

The Gentleman Tramp2004

The Life and Art of Charles Chaplin

2. Scored or Retro-Scored by Chaplin

3. Oscar™ Nominated 4. Oscar™ Winner | ||

As there has been so much written on the life of Charlie Chaplin, this biography will largely focus on and take into context the parts of his life as a composer and musician, while still covering the major events and time line. Chaplin was not really a ragtime composer per se, but he did what he could to keep music viable in his films by directing the use of certain pieces or genres of pieces, and eventually composing them as well. Many of these works made it into print as far back as the mid-1910s, and a handful endure today. So his music was born out of the melding of ragtime and popular music as it accompanied early silent films, and therefore he should be not be ignored as a composer who drew on that era for some of his work. But he went well beyond that, as will be seen here, and should further be acknowledged for the boldness he displayed in scoring some of his later films as well, putting him also in the category of film composer.

As there has been so much written on the life of Charlie Chaplin, this biography will largely focus on and take into context the parts of his life as a composer and musician, while still covering the major events and time line. Chaplin was not really a ragtime composer per se, but he did what he could to keep music viable in his films by directing the use of certain pieces or genres of pieces, and eventually composing them as well. Many of these works made it into print as far back as the mid-1910s, and a handful endure today. So his music was born out of the melding of ragtime and popular music as it accompanied early silent films, and therefore he should be not be ignored as a composer who drew on that era for some of his work. But he went well beyond that, as will be seen here, and should further be acknowledged for the boldness he displayed in scoring some of his later films as well, putting him also in the category of film composer.Early Years

Charles Spencer Chaplin was born in England to Charles Chaplin and Hannah Hill, both performers in London music halls. Named after his father and his uncle, Spencer Chaplin, Charles had an older brother, Sydney (John Hill) Chaplin (1885), by a different father, whose identity has never been fully confirmed, but is considered by a handful of researchers to be a Sydney Hawkes.![The Girl Was Young and Pretty composed by Charles Chaplin [Sr.] and published in London c.1890 the girl was young and pretty sheet music](/images/youngandpretty.jpg) Charles Chaplin Sr. was a talented actor and singer, and even a published composer. One of his pieces was The Girl was Young and Pretty, the theme of which was later echoed in his 1992 film biography directed by Sir Richard Attenborough. Another was a poignant waltz song called Every-Day Life with lyrics by Harry Boden from 1891. The sheet music advertised that it had been "Composed and Sung with Enormous Success by Charles Chaplin." However, he was also an alcoholic, and ended up separating from Hannah when Charlie was around two. In the 1891 England census Hannah Chaplin is listed as an unemployed professional singer residing with Sydney and young Charles in the St. Mary district. Hannah showed as being married, but without her husband in the household. He was living nearby in the same district in a boarding house with other music hall artists.

Charles Chaplin Sr. was a talented actor and singer, and even a published composer. One of his pieces was The Girl was Young and Pretty, the theme of which was later echoed in his 1992 film biography directed by Sir Richard Attenborough. Another was a poignant waltz song called Every-Day Life with lyrics by Harry Boden from 1891. The sheet music advertised that it had been "Composed and Sung with Enormous Success by Charles Chaplin." However, he was also an alcoholic, and ended up separating from Hannah when Charlie was around two. In the 1891 England census Hannah Chaplin is listed as an unemployed professional singer residing with Sydney and young Charles in the St. Mary district. Hannah showed as being married, but without her husband in the household. He was living nearby in the same district in a boarding house with other music hall artists.

![The Girl Was Young and Pretty composed by Charles Chaplin [Sr.] and published in London c.1890 the girl was young and pretty sheet music](/images/youngandpretty.jpg) Charles Chaplin Sr. was a talented actor and singer, and even a published composer. One of his pieces was The Girl was Young and Pretty, the theme of which was later echoed in his 1992 film biography directed by Sir Richard Attenborough. Another was a poignant waltz song called Every-Day Life with lyrics by Harry Boden from 1891. The sheet music advertised that it had been "Composed and Sung with Enormous Success by Charles Chaplin." However, he was also an alcoholic, and ended up separating from Hannah when Charlie was around two. In the 1891 England census Hannah Chaplin is listed as an unemployed professional singer residing with Sydney and young Charles in the St. Mary district. Hannah showed as being married, but without her husband in the household. He was living nearby in the same district in a boarding house with other music hall artists.

Charles Chaplin Sr. was a talented actor and singer, and even a published composer. One of his pieces was The Girl was Young and Pretty, the theme of which was later echoed in his 1992 film biography directed by Sir Richard Attenborough. Another was a poignant waltz song called Every-Day Life with lyrics by Harry Boden from 1891. The sheet music advertised that it had been "Composed and Sung with Enormous Success by Charles Chaplin." However, he was also an alcoholic, and ended up separating from Hannah when Charlie was around two. In the 1891 England census Hannah Chaplin is listed as an unemployed professional singer residing with Sydney and young Charles in the St. Mary district. Hannah showed as being married, but without her husband in the household. He was living nearby in the same district in a boarding house with other music hall artists.To compound an already difficult situation, Hannah had some mental illness, and her inability to keep jobs required the broken family to move from place to place around Kensington Road, so as to be close enough to the theaters. Yet they still lived in relative comfort above the poverty level. Charles had constant exposure to the stage, and to the music as well. His mother, who worked under the name Lilly Harley, preferred to bring the boys to the theater rather than leave them alone, so they quickly became familiar with the songs of the day, bawdy and otherwise. They would occasionally see Charles Sr. perform as well, even after he had left the family. One of his frequent haunts was the Canterbury Music Hall.

As Charles relayed it in his autobiography, his first time on stage was when he was but five years old. He was backstage at the Aldershot Canteen while Hannah was performing for a group largely made up of soldiers. She was having a rough time of it, her voice cracking during her song. Whether Charles ventured out after she left the stage or whether he was pushed on remains conjecture or hearsay (he claims the latter). However, he took over for his mother, singing two or three songs, one of them being Jack Jones, and picking up coins thrown on stage by the amused audience in response to his work before he left. It was the start of a very long career performing for the public, and was claimed to be his mother's last night on stage.

Following this, Hannah, who had been prone to increasing bouts of laryngitis, was no longer able to work consistently as a singer, leaving the family of three suddenly living day to day in poverty. After a year or so they had to retreat to the workhouses, and at times were separated. Hannah recovered briefly, then had a breakdown. She was sent to Cane Hill Asylum at Coulsdon for recovery,

and Charles and Sydney were sent off initially to live with their father and his mistress Louise for a while. She, in turn, sent them to the Archbishop Temples Boys School, and had a tenuous relationship with Charles and Sydney. This was exacerbated by her drinking as well as their fathers, and the presence of a boy in the home who was four years younger. This was Charles' other half-brother, but he did not know it at that time. After a few months the boys went back again to live their mother after she was released. However, she was not able to properly care for them, and was again committed to the asylum while the boys were sent to a school for paupers. Sydney eventually went to sea and Charlie was at times out on the streets fending for himself.

|

Even as a juvenile performer Chaplin claims he had not yet really discovered music. However, he told of that day in his biography, leaving the impression that he was perhaps eight at the time. Charles had come home to his father's empty house, and bored after a while he wandered out into the streets again to try to find food and solace. As he tells it: "Suddenly, there was music. Rapturous! It came from the vestibule of the White Hart corner pub, and resounded brilliantly in the empty square. The tune was The Honeysuckle and the Bee, played with radiant virtuosity on a harmonium and clarinet. I had never been conscious of melody before, but this one was beautiful and lyrical, so blithe and gay, so warm and reassuring. I forgot my despair and crossed the road to where the musicians were... It was all over too soon and their exit left the night even sadder... It was here that I first discovered music, or where I first learned its rare beauty, a beauty that has gladdened and haunted me from that moment."

Charles first worked as a billed artist in 1898 with a group of pre-teen clog dancers. They were called The Eight Lancashire Lads, and the experience allowed him to hone his agility of movement as well as gain a better sense of timing and rhythm in conjunction with the musical accompaniment. Although the work was necessary to help support his family, he was thoroughly at home on the stage, and became quite acrobatic as a result of his time as a dancer. He reportedly may have also done some singing and a little comedy with this act, but there is no direct billing that fully supports this contention. As of the 1901 England census he was rooming with a troupe of actors, possibly the clog dancers. Like the others, Charles was listed as a "music hall artiste." Neither his mother or Sydney were residing there, but he was one of ten juveniles living in the flat of John Jackson, son of the troupe's leader who himself was all of seventeen. That same year, Charles Sr. finally died at age 37 from cirrhosis of the liver and complications related to alcohol abuse.

At twelve and a half years of age after a year of odd jobs, and shortly after his mother was recommitted to Cane Hill, Charlie managed to snag a plum role in the C.E. Hamilton Company as Billie the Page Boy in a production of Sherlock Holmes. After getting good reviews in an otherwise poor play staged before the Sherlock Holmes tour, he continued in the role for three seasons. In the fourth season he ended up playing the same role opposite the author of the play. The four years emboldened him as an actor and established his stage presence, but not prepare him for comedy. Now sixteen and a bit cocky, Charlie decided to turn down the next role because it required traveling. As a result, he spent nearly a year not working.

Steady work of any kind was hard to come by, so he was supported in part by Sydney, who had been with British performer and producer Fred Karno's comedy company since 1906. Charles secured some music books and Jewish humor jokes, attempting to make a splash as an ethnic comedian. He was ill-prepared to do direct comedy as opposed to character comedy, and this venture lasted one performance. There were other minor failures on stage as well. Then at age nineteen Charlie, morally supported by Sydney, secured a position with Karno as a replacement actor playing opposite comedian Harry Weldon in a sketch called The Football Match.

Within a week he had a long-term contract with Karno, and his career as a comic actor was finally established.

|

Working in various groups of Karno's traveling organization, Charlie quickly became a star of the sketch and pantomime comedy sketches, and his timing and choices were evidently highly regarded by the boss. It has been noted that his use of music in his act fully availed itself of the possibilities presented in the rhythmic and melodic elements of a tune, adding to the overall essence of his act. The acts often used classic 18th and 19th century melodies accompanied by sound effects or slapsticks to emphasize falls or other actions, which gave his form of comedy its name, even before he became associated with it. Among the actors he worked with during his time with Karno was another future comedy star, was Arthur Stanley Jefferson, known on stage as Stan Laurel. Stan ultimately served as Chaplin's understudy and backup while with the Karno company.

Charlie met a girl in the chorus line named Hetty Kelly and was instantly transfixed by her. His emotions for her became so strong that on their first outing he referred to her as his "nemesis," which she could not understand. Within days he had asked if she loved him, which she felt unfair given that Hetty was just short of sixteen to his nineteen years. Chaplin ended it right there after all of four encounters, but went to her home the following day to say goodbye once more just to be sure. He would never forget Hetty, and subconsciously would search for her over the next 34 years. In fact, when he met her just over a year later she was now seventeen and well-developed, but not the same girl in many ways, so he continued searching.

The Karno company toured Europe a couple of times from 1909 to 1910. At one show in Paris presented at the famous Folies Bergère, composer Claude Debussy was in the audience with a lady friend from the Russian ballet, and asked to meet Charlie after the show. The impressionist composer told him, "You are instinctively a musician and a dancer." While this was clearly a great compliment to Charlie, he was not sure how to reply, and he did not know who Debussy was at that time. However, he eventually knew all to well, noting in his autobiography it was the same year that "Debussy introduced his Prélude à L'Après Midi d'un Faune [Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun] to England, where it was booed and the audience walked out."

Charlie toured Canada and the United States extensively with the American Karno company from late September 1910 to early 1912. They entered the United States on October 1 after having arrived a few days earlier to Quebec on the Cairnrona, and proceeded quickly to New York City for their first engagement of six weeks. Reports that he was the featured star entertainer with the troupe on that trip are not fully supported by newspaper advertising of that time until closer to the end of the tour, which was extended for twenty weeks to the west, another six in New York, and another twenty in the west again. Among the acts that toured was one titled The Wow Wows that featured Charles as "The Original Souse." In late 1912 the core of the Karno company again ventured to America to tour the vaudeville circuit for another year, arriving this time in New York Harbor on October 12 aboard the Oceanic as second class passengers. One of Chaplin's specialties in the Night in an English Music Hall sketch was playing an inebriated souse much older than himself, who randomly invaded the audience, then the stage, with his drunken antics.

One of Chaplin's specialties in the Night in an English Music Hall sketch was playing an inebriated souse much older than himself, who randomly invaded the audience, then the stage, with his drunken antics.

One of Chaplin's specialties in the Night in an English Music Hall sketch was playing an inebriated souse much older than himself, who randomly invaded the audience, then the stage, with his drunken antics.

One of Chaplin's specialties in the Night in an English Music Hall sketch was playing an inebriated souse much older than himself, who randomly invaded the audience, then the stage, with his drunken antics.Stan Laurel remembered several facets of this second trip and recounted some information about Chaplin in a later interview with historian John McCabe. "Charlie carried his violin wherever he could. Had the strings reversed so he could play left handed, and he would practise for hours. He bought a cello once and used to carry it around with him. At these times he would always dress like a musician, a long fawn coloured overcoat with green velvet cuffs and collar and a slouch hat. And he'd let his hair grow long at the back. We never knew what he was going to do next." This concurs with Chaplin's own account of his first trip to the states: "On this tour I carried my violin and cello. Since the age of sixteen I had practised from four to six hours a day in my bedroom. Each week I took lessons from the theatre conductor or from someone he recommended. As I played left handed, my violin was strung left handed with the bass bar and sounding post reversed. I had great ambitions to be a concert artist, or, failing that, to use it in a vaudeville act, but as time went on I realised that I could never achieve excellence, so I gave it up."

It also during the second trip while they were playing in New York City that Chaplin went to the Metropolitan Opera House to see the opera Tannhäuser, something that may have influenced even more his sense of the melding of music and storytelling. According to Charlie: "I had never seen grand opera, only excerpts of it in vaudeville — and I loathed it. But now I was in the humour for it. I bought a ticket and sat in the second circle. The opera was in German and I did not understand a word of it, nor did I know the story. But when the dead Queen was carried on to the music of the Pilgrim's chorus, I wept bitterly. It seemed to sum up all the travail of my life. I could hardly control myself; what people sitting next to me must have thought I don't know, but I came away limp and emotionally shattered."

On the 1912 to 1913 trip Chaplin was clearly the star of the Karno troupe in their primary sketches, A Night in an English Music Hall and The Wow Wows. While on the second American tour, Charlie was witness to, and soon was entranced by the growing medium of motion pictures, now well into their second decade. The notion of putting something into a permanent record that could be viewed by potentially millions in a short time, as opposed to hundreds in a week, was appealing to him, as was the potential in what was a forced pantomime. So near the end of 1913 when his contract with Karno expired, Chaplin decided to achieve his own success in America and left the company to pursue a career in the movies.

The Cinema and Rise to Fame

|

Actress Mabel Normand took up Charlie's cause and insisted that Sennett give him another chance under her tutelage. Although he had issues with a woman directing his acting, Chaplin persevered and came back strong in the next film, Mabel's Strange Predicament.. According to his autobiography Sennett had asked him to dress in a comedy make up of some kind. The famous incident with him finding his new identity was poetically recreated in the 1992 biopic Chaplin starring Robert Downey Jr., but Chaplin's own passage was actually a bit more practical:

I had no idea what makeup to put on. I did not like my get-up as the press reporter [in the previous film Making a Living]. However on the way to the wardrobe I thought I would dress in baggy pants, big shoes, a cane and a derby hat. I wanted everything to be a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large. I was undecided whether to look old or young, but remembering Sennett had expected me to be a much older man, I added a small moustache, which I reasoned, would add age without hiding my expression. I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the makeup made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on stage he was fully born...

[Sennett] stood and giggled until his body began to shake. This encouraged me and I began to explain the character: 'You know this fellow is many-sided, a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure. He would have you believe he is a scientist, a musician, a duke, a polo-player. However, he is not above picking up cigarette-butts or robbing a baby of its candy. And, of course, if the occasion warrants it, he will kick a lady in the rear — but only in extreme anger!'"

In reality, the hat and oversized pants came from the rotund Arbuckle and the shoes from Ford Sterling. The concept itself was evocative of his early years living in poverty and making due with whatever was at hand. While the tramp did appear briefly in Mabel's Strange Predicament, the first film that featured that character, shot the following week, was Kid Auto Races at Venice released in early February 1914. The simple plot had him mugging annoyingly for the camera at a soapbox derby race while directors and cameramen try to keep him out of the picture. The tramp character immediately caught on with audiences, and several more shorts were made featuring Chaplin. He immediately adopted the oversized shoes, baggy pants, and penguin-like walk that made him stand out. Charlie did play a Keystone Kop in one recently discovered short, but once the tramp character was established he rarely veered away from his creation. Little known to most of the public, the tramp also had a name, the French derivative of his own, Charlot.

By the middle of the year Chaplin shorts were drawing crowds, and they were appearing frequently in advertising, often trumping the feature they were playing with. It was clear to Sennett and Chaplin that $150 per week was hardly appropriate any more, and the two tussled over numbers for the remainder of the year. Chaplin also wanted more control over scenarios, editing, and even directing. He was now making $175 per week plus a $25 bonus for each completed film. Sennett and Chaplin were often at odds, but the studio head put up with it because his revenues had increased significantly thanks to Charlie's films. Even before the end of 1914, Chaplin was the most famous movie comedian, and arguably the most famous comic actor in the United States. During his one year contract Charlie appeared in 36 Keystone films, a brutal pace considering the amount of physical action and location shooting done in the early days of film.

It was a show of respect by Sennett that he did not openly contest Chaplin leaving his organization to work for Essanay Studios (S and A for owners George K. Spoor and cowboy star G.M. "Bronco Billy" Anderson) in 1915 for a great deal more money. News reports of the time put it at over $100,000 for the year. By then, Sydney had also come to the United States, and for a time replaced his brother in Keystone comedies. At Essanay Charlie was given a bit more freedom to develop his gags, and regularly used a stock set of actors for consistency. Among them was a young lady named Edna Purviance and villains Bud Jamison and Leo White. Essanay managed to distribute Chaplin films to every corner of the country and heavily advertised their star property as well. Chaplin films even managed big draws in New York City, where entertainment was available at every turn. However, much of the crowd seeking entertainment from the tramp were immigrants who still did not have command of the English language, and did not really need to in order to grasp the universal pantomime slapstick that Charlie was mastering.

News reports of the time put it at over $100,000 for the year. By then, Sydney had also come to the United States, and for a time replaced his brother in Keystone comedies. At Essanay Charlie was given a bit more freedom to develop his gags, and regularly used a stock set of actors for consistency. Among them was a young lady named Edna Purviance and villains Bud Jamison and Leo White. Essanay managed to distribute Chaplin films to every corner of the country and heavily advertised their star property as well. Chaplin films even managed big draws in New York City, where entertainment was available at every turn. However, much of the crowd seeking entertainment from the tramp were immigrants who still did not have command of the English language, and did not really need to in order to grasp the universal pantomime slapstick that Charlie was mastering.

News reports of the time put it at over $100,000 for the year. By then, Sydney had also come to the United States, and for a time replaced his brother in Keystone comedies. At Essanay Charlie was given a bit more freedom to develop his gags, and regularly used a stock set of actors for consistency. Among them was a young lady named Edna Purviance and villains Bud Jamison and Leo White. Essanay managed to distribute Chaplin films to every corner of the country and heavily advertised their star property as well. Chaplin films even managed big draws in New York City, where entertainment was available at every turn. However, much of the crowd seeking entertainment from the tramp were immigrants who still did not have command of the English language, and did not really need to in order to grasp the universal pantomime slapstick that Charlie was mastering.

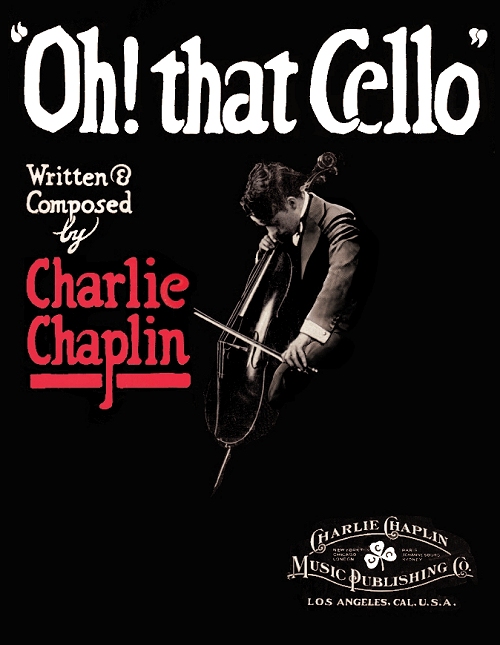

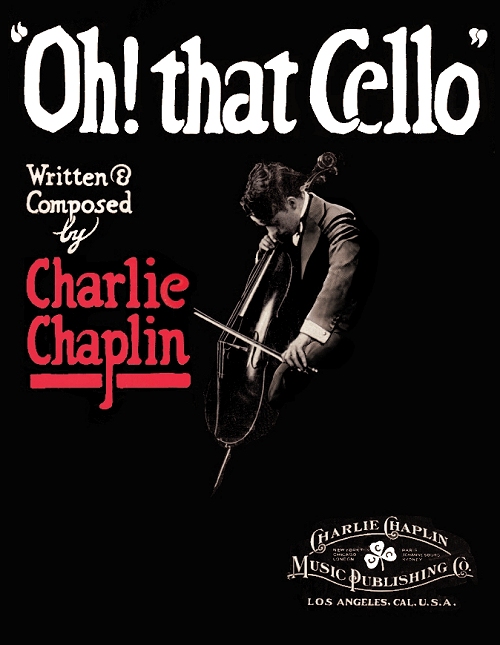

News reports of the time put it at over $100,000 for the year. By then, Sydney had also come to the United States, and for a time replaced his brother in Keystone comedies. At Essanay Charlie was given a bit more freedom to develop his gags, and regularly used a stock set of actors for consistency. Among them was a young lady named Edna Purviance and villains Bud Jamison and Leo White. Essanay managed to distribute Chaplin films to every corner of the country and heavily advertised their star property as well. Chaplin films even managed big draws in New York City, where entertainment was available at every turn. However, much of the crowd seeking entertainment from the tramp were immigrants who still did not have command of the English language, and did not really need to in order to grasp the universal pantomime slapstick that Charlie was mastering.Charlie had another trick up his sleeve as well, making an attempt at a popular song in 1915.He sought to have his music heard in America. When Oh! That Cello was self-published in 1915 it had a slow start. But after a piano roll of it was released the following year the name association caused some head scratching and curiosity in the music industry, as reported in The Music Trade Review of September 9, 1916.

CONSIDERABLE anxiety has been expressed in various quarters to know whether the Charles Chaplin who appears as the composer of "Oh that 'Cello" in the August bulletin of the Q R S Co. is in reality he of the slap-stick motion picture comedy fame. The Q R S Co. aver that it is the simon pure Charles. He is doing quite a bit of composing nowadays between acts, so to speak, and moreover is publishing his own compositions. "Oh that 'Cello" is quite pleasing even to the ear of one who does not revel in the popular music of the day. Lee Roberts [main arranger and vice president of QRS] made a hand played roll of it and has a nice letter from the real Charles written from Los Angeles giving his permission for its inclusion in the Q R S catalog.

Even before the discovery that Chaplin was a composer, composers discovered Chaplin, and in 1915 alone no less than eight pieces named for Charlie or his feet were in the stores. The most popular of them were That Charlie Chaplin Walk and Those Charlie Chaplin Feet. The reason such a comic association between music and Chaplin's screen persona seemed so natural is that it often was. Chaplin, like many other fine comic actors, knew that there were layers of rhythm within the concept of "comic timing." Even today, scripts for television and movies often use the term "take a beat" or "two beats" at times, informing the actor to pause for an amount of time that would be analogous to the current pace of the action. Sennett often had musicians in his employ to provide not only mood music but rhythm to help the flow of action for the actors.

The reason such a comic association between music and Chaplin's screen persona seemed so natural is that it often was. Chaplin, like many other fine comic actors, knew that there were layers of rhythm within the concept of "comic timing." Even today, scripts for television and movies often use the term "take a beat" or "two beats" at times, informing the actor to pause for an amount of time that would be analogous to the current pace of the action. Sennett often had musicians in his employ to provide not only mood music but rhythm to help the flow of action for the actors.

The reason such a comic association between music and Chaplin's screen persona seemed so natural is that it often was. Chaplin, like many other fine comic actors, knew that there were layers of rhythm within the concept of "comic timing." Even today, scripts for television and movies often use the term "take a beat" or "two beats" at times, informing the actor to pause for an amount of time that would be analogous to the current pace of the action. Sennett often had musicians in his employ to provide not only mood music but rhythm to help the flow of action for the actors.

The reason such a comic association between music and Chaplin's screen persona seemed so natural is that it often was. Chaplin, like many other fine comic actors, knew that there were layers of rhythm within the concept of "comic timing." Even today, scripts for television and movies often use the term "take a beat" or "two beats" at times, informing the actor to pause for an amount of time that would be analogous to the current pace of the action. Sennett often had musicians in his employ to provide not only mood music but rhythm to help the flow of action for the actors.Chaplin sometimes did the same, and he also knew the importance of both acting and editing in such a way that music played to his films, the big end factor over which he had virtually no control over at that time, would naturally find a sweet spot through his pacing. Many of the songs about Chaplin fit that mold nicely, and were not only used to accompany some of his films but sold in the lobbies as well. Others were featured on stage, managing to make the presence of Charlie known even at the popular Ziegfeld Follies. Chaplin himself made it known that certain popular piece might even inspire action sequences or scenarios. "Simple little tunes gave me the image for comedies. In one called Twenty Minutes of Love, full of rough stuff and nonsense in parks, with policemen and nursemaids, I weaved in and out of situations to the tune of Too Much Mustard, a popular two step in 1914. The song Violetera set the mood for City Lights, and Auld Lang Syne the mood for The Gold Rush."

Chaplin's first Essanay film was made at their Chicago headquarters, a place he deplored. So he went to their studio in Niles, California, which was situated near the San Francisco Bay area and featured very usable old-west scenery. During the process of making his fourteen films at Essanay Charlie's musical proclivities became better known to his colleagues. He bought a higher quality violin, perhaps favoring it over the cello. It was said that he would "scrape away" at the instrument for several hours at night. As he and the other actors were often housed next to the studio at Niles, Chaplin staying in the surprisingly sparse quarters of millionaire Bronco Billy, they would often suffer through sleepless nights listening to Chaplin trying to master the instrument. That misery did not last long. After four more films Chaplin retreated to Southern California and rented a studio near downtown Los Angeles for the remaining Essanay films.

|

After a successful but sometimes choppy run with Essanay in 1915, Sydney arranged a lucrative agreement for his brother for $670,000 ($10,000 per week plus a $150,000 signing bonus) with the Mutual Film Corporation for twelve two-reel comedies in 1916, one per month. Mutual wisely gave him more or less carte blanche in terms of artistic control, content and personnel. The same was true in terms of time, because as the Mutuals went along Chaplin required a longer shooting and editing schedule. The initial twelve months stretched into just over eighteen. However, every one of the twelve films has remained a classic for nearly a century, and Chaplin stated in his autobiography that it was the most productive and happiest period of his career.

Mutual allowed Chaplin to form his own separate production arm named Lone Star Productions. In spite of his success with the tramp, the character was not featured in all of these shorts. In The Fireman he is obviously a fireman in and The Cure Chaplin plays an alcoholic who checks into a sanatorium. One of most unique Mutuals, One A.M., features Chaplin as an adventurous bachelor who arrives home quite inebriated and has to negotiate the hazards of his own home in order to get to bed, or something like a bed. There is a clear rhythmic pace in this solo effort that is punctuated by a wall clock with an oversized widely swinging pendulum. In The Vagabond he played a saloon violinist who rescues a girl from a cruel gypsy master. In it he is seen playing in his usual left-handed manner. The Rink, Easy Street and The Pawnshop have also remained favorites.

Chaplin's new role as a comic leading man opened many doors to him, but also brought obligations. He was asked to do benefits and promote causes.

In one instance he did a benefit at the famous Hippodrome in New York City. A filmed snippet remains that is thought to be from that benefit. It shows Chaplin in his guise as a musician, conducting the band half seriously while clowning around with them. Even though the appearance was staged, it had an air of spontaneity and joy. His fame also brought him many visitors and admirers. Among those wer two men that Chaplin himself had admired for some time, pianists Ignace Jan Paderewski and Leopold Godowsky, the latter who posed with Charlie in late 1916. There is no account of any lessons being given in either music or comedy during that visit. Chaplin also built up a fine ensemble cast and crew. In addition to his leading lady and constant companion Edna Purviance, who he was romantically involved with during 1916 and 1917, he brought in his half-brother Sydney as both agent and manager, and added a comic giant villain, Scottish import Eric Campbell, to his stock company. Charlie had known the 6'4" Campbell from the Karno company, and he was described as a very gentle giant. During the Mutual run Campbell lost his wife to sickness, and subsequently got involved in a sham marriage. Sadly, after the last Mutual production was finished, Eric died instantly in a tragic car accident on Wilshire Blvd. in December 1917, the result of too much alcohol.

|

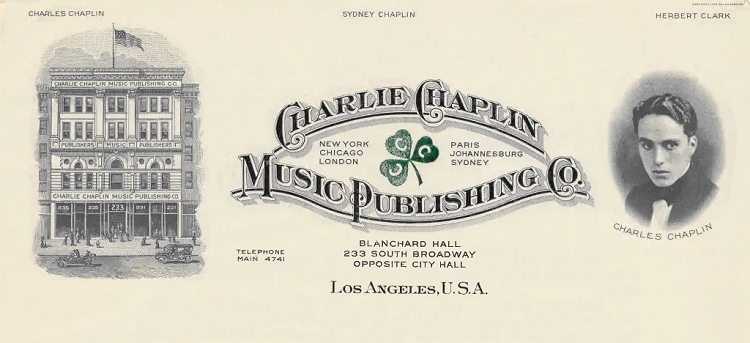

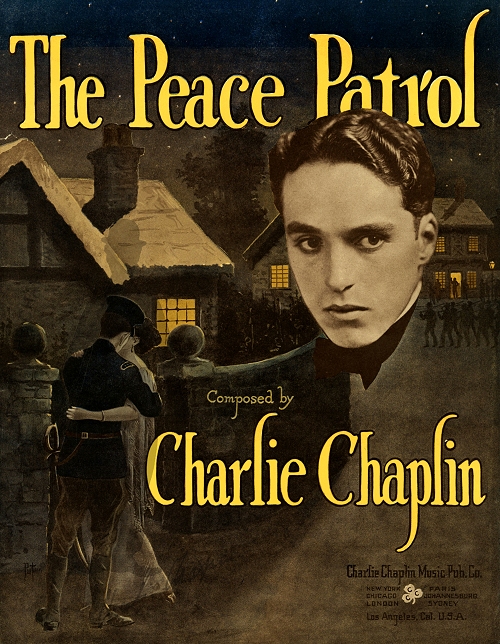

To further extend his control over his end products, Charlie had formed the Charles Chaplin Music Company with comedian and pianist Bert Clark to publish Oh! That Cello. He likely had big plans for that concern, but in its short life of perhaps two months or so only two more pieces were published. The Peace Patrol was a simple but lyrical instrumental march.

While he was negotiating with the Mutual Company in New York City, Chaplin appeared at a benefit concert at the Hippodrome on February 20, 1916. There he led Sousa's band in the Poet and Peasant Overture, followed by The Peace Patrol, perhaps its only public performance in his lifetime. This composition was followed by There's Always One You Can't Forget, a sentimental piece about his first true love, Hetty Kelly. (In 1921 he found out that Hetty had died during the flu pandemic which devastated him.) As for his publishing activities, Chaplin recalled that, "[Bert and I] had rented a room three storeys up in a down town office building and printed two thousand copies of two very bad songs and musical compositions of mine — then we waited for customers. The enterprise was collegiate and quite mad. I think we sold three copies, one to Charles Cadman, the American composer, and two to pedestrians who happened to pass our office on their way downstairs."

|

In the latter half of 1917 after nearly 18 months, Charlie left Mutual, where he later said he had enjoyed the best period of his life. He signed with First National for a contract of eight two-reel films (some would be longer). The money and freedom they gave him in addition to what he had earned from Mutual allowed Chaplin to build his own studio in Hollywood (presently the home to Disney's Jim Henson Studios). Chaplin remembered that "At the end of the Mutual contract, I was anxious to get started with First National, but we had no studio. I decided to buy land in Hollywood and build one. The site was the corner of Sunset and La Brea and had a very fine ten-room house and five acres of lemon, orange and peach trees. We built a perfect unit, complete with developing plant, cutting room, and offices." He met with resistance from a local residential neighborhood who opposed the encroachment, but ultimately was allowed to built by the city council. Sydney also joined him in this effort, becoming Charlie's manager. He played a comic role of a food vendor in Chaplin's first film for the company, A Dog's Life, released in 1918.

He played a comic role of a food vendor in Chaplin's first film for the company, A Dog's Life, released in 1918.

He played a comic role of a food vendor in Chaplin's first film for the company, A Dog's Life, released in 1918.

He played a comic role of a food vendor in Chaplin's first film for the company, A Dog's Life, released in 1918.From the time of the Great War (World War I) on there was some obvious controversy concerning Chaplin's patriotism towards the United States, more a reflection of his perceived political views than anything. One that persisted was that he tried to avoid the draft or enlistment. This is not true, and he indeed filled out a draft card on June 5, 1917, listing himself as moving picture comedian working for the Lone Star Company, the name of the production company he had formed at Mutual. In fact, it has been reported that Chaplin made three attempts [at least two confirmed] to enlist in either the American or British armies, and was rejected for one or another reason. At 5'6" and a mere 125 pounds he was a bit slight to be a soldier. Even though he was not a naturalized citizen, that fact did not make him ineligible. He had wanted to enlist in the British Army, but his Mutual contract stipulated that he remain the United States until it was fulfilled. Not knowing this, soldiers in the British army adopted a nasty parody, sung to Red Wing by Kerry Mills, called The Moon Shines Bright on Charlie Chaplin, suggesting he be sent to the Dardanelles where a bloody campaign had taken place.

It is known that Chaplin was seen as an important entity in his capacity as an actor, as he was not yet involved with so-called subversive organizations or activities. He was also quite active in promoting the sale of bonds during a national tour with Mary Pickford, best friend Douglas Fairbanks, and actress Marie Dressler. This was followed by a short called The Bond, made at his own expense, which was used by the Federal Government to further promote sales. It explained several types of bonds, including friendship and marriage, ending with the most important type, Liberty Bonds. A final scene showed him wielding a larger mallet with "Liberty Bonds" painted on it, which he used to successfully pummel the Kaiser (played by Sydney), in a comical manner, of course. One of his early films through First National was the war-themed feature Shoulder Arms, which was a large success at the box office and considered by historians to be the best World War I film actually during the conflict. In it, Sydney reprises his role as the much abused Kaiser.

By mid 1917, most theaters in the United States had house musicians playing either piano or organ, or in some cases ensembles ranging from three piece groups to orchestras. In smaller towns it would often be a piano teacher or her star student playing classical tunes or the latest popular songs and rags to the films for some extra cash. For the most part, with few exceptions, there were no definitive music scores for movies, especially for the shorts.

D.W. Griffith had commissioned scores for a couple of his feature films, but they were typically only used in the very largest metropolitan centers and not reduced to a piano or organ score. The following year would see the introduction of theme songs associated with films, but one song a score did not make.

|

Chaplin was well aware of this shortfall, and in particular recognized how the proper underscore would add to the emotional import of the action on the screen. Along with some other directors and producers his company sent out simple suggestions for the type of music to play for each scene, even with some popular titles. While this was not the same as a score, the guidance provided more consistency for film goers as long as the local musicians were capable of following these directions.

The first hint of coming disasters in his life came about in 1918 when Charlie, then 29, married a popular 18-year-old actress, Mildred A. Harris, a quickly formed union predicated on a pregnancy that turned out to be a false alarm. While their relationship seemed to be smooth at the start, things quickly fell apart after Mildred actually did get pregnant, then gave birth to a son, Norman Spencer Chaplin. Sadly, the child died at three days old on July 10, 1919. The couple was never able to fully reconcile, and Charlie set out on a series of affairs that occasionally made it into the press, not helping his image or his questionable marriage.

Being a top personality in show business, his endorsement was sought out by many companies, one comical example which was relayed in The Music Trade Review of December 21, 1918:

Charlie Chaplin received a letter from a certain manufacturer of musical instruments, proposing to present him with a saxophone providing he would be photographed with it, and permit the maker to use the indorsement [sic] for advertising purposes. Not being particularly interested in the saxophone but appreciating the gentleman's courtesy, Mr. Chaplin in part replied: "If you happen to have a spare 'Strad' violin knocking about that you don't want, well, you might send it on. I will have my picture taken with it, and I will give you a letter to the effect that I can thoroughly recommend it."

On February 5, 1919, with his new studio fully built and in production for a year now, Charlie joined one of the earliest ongoing efforts to promote individualistic freedom and support for film makers. Along with Sydney and their actor friends Mary Pickford (America's sweetheart), Douglas Fairbanks (America's screen hero), William S. Hart (America's favorite cowboy) and legendary director David W. Griffith, the group formed the United Artists production and distribution company. They had heard, in part through a woman detective they had hired, that some of the larger studios and distributors were banding together, which would have created a monopoly in the business, with little of the money going to the artists.

As was Chaplin's hope, the idea behind this organization was to allow the stars to be their own bosses. Through UA they had to do their own financing for projects, but they also were able to reap more of the profits, which had traditionally gone to the producers of films. Yet at the time he helped form the organization, Charlie still had an obligation of six films to complete with First National in order to exercise that freedom. Charles and Mildred appeared in the 1920 census living 674 Oxford Way in Beverly Hills with a live-in chef and his wife. They both listed their occupation as a motion picture actor and actress respectively.

|

In 1919 he completed two more films, the unusual three reel Sunnyside and the more traditional two rell A Day's Pleasure, the latter of which included several potential vomiting jokes. His next film for them was a six-reel feature, The Kid, starring child actor Jackie Coogan (who would later act as Uncle Fester on The Addams Family) along with Chaplin. Much more than a comedy it went through a variety of emotions including tragedy, sentiment and pure pathos. Charlie wanted this particular release to have something more attached to it. So The Kid was distributed with fairly specific cue sheets with title lists, and in some packages music as well. While this was not a Chaplin score per se, it helped him realize something much closer to the overall intent and emphasized the importance in which he held music as an important entity and even a character in his films. Joe Bren and Haven Gillespie wrote a song specifically for the film, but there is some uncertainty as to whether this piece was included in the official recommendations.

There may have been more music composed during the final stages of the film, but Charlie would not have time to tend to that. Mildred had filed for divorce and was reportedly attempting to seize his assets. In the process she had also publicly accused him of being a "red," or a Bolshevist sympathizer, the first time he would have to counter such a charge. Charlie had already moved out and was living in the Los Angeles Athletic Club, rather than at the apartment he had built at his studio. He had stirred the waters by suggesting that Harris was engaging in lesbian activities with other young actresses. Concerned that the authorities may move in, in the middle of the night Chaplin grabbed all of the film stock from The Kid and with Sydney's assistance moved it to a hotel room in Salt Lake City, Utah, where the editing was completed by Charlie himself. Upon the discovery that he was in Utah, where the authorities did not arrest or extradite him, one newspaper article observed of the 31-year-old star that "Charlie's hair is growing gray." Even without the full suggested score that he had hoped to assemble for the premier events, the movie was a huge hit and his reputation was kept intact. Mildred ended up with some of their joint property and a $100,000 settlement in November 1920. She would overspend and be bankrupt within two years.

Needing a break after the traumatic events involving The Kid, and the efforts involved in his next film, The Idle Class, in which he played two roles, Charlie sailed for England on the Olympic in late August, 1921, arriving in Southampton, England, on September 1. While he was aware he had achieved some level of fame on the continent and in his original home of London, Chaplin was quite awe struck and moved by the reception he received there. He also met with author H.G. Wells, but his hopes for a private meeting were dashed by the large crowds hanging around their rendezvous point.

There were also some dissenters in London who had misunderstood his role in the Great War, so he ended up more or less escaping his original home and the mix of joy and angst he found there.

|

He left for Paris, then Berlin, and there met with Albert Einstein and his wife. Everywhere he went Charlie was met by large crowds who revered his talent, and underscored how universal his pantomime comedy, which transcended language barriers, actually was. Back in Paris Charlie reluctantly appeared at a benefit showing of The Kid, then retreated back to London. There he was able to spend more time with Wells and a number of British dignitaries who sought an audience with him. After a seven week vacation, Chaplin returned to New York, then Hollywood to resume his work with new energy. On the returning passenger list on the Berengaria, dated October 17, 1921, his nationality is listed as English. However it was apparently and inaccurately altered on February 7, 1936, with English written over with Hebrew for unknown reasons.

Chaplin made two more films to finish off his First National contract, Pay Day and The Pilgrim. While there was no specific score composed for these at that time (some of his early films would be scored in later years by Chaplin), they were accompanied by the same sort of cue sheets as had been sent out with The Kid. But as his films progressed, he was already experimenting more with composition, and in his leisure time was engaged ever more with performance.

Having made his first million and more, Charlie first procured a Brambach Welte-Mignon reproducing piano in late 1919. In 1922 he bought a Bilhorn Telescope Organ, a portable device that allowed him to take his music on the set with him. Chaplin then had an expensive Robert-Morton Pipe Organ installed in his new Beverly Hills mansion as it was being built in 1923. It was reported that he often sat at it for hours at a time playing older melodies and composing new ones. The procurement of the instrument was described in the music trade magazine Presto on February 3, 1923:

Movie fans in the country seldom realize the true character of their screen stars. Screen action, plot, and the vehicle representing our favorite doesn't always fully interpret the temperament of the actor.

It may be news to many readers that Charlie Chaplin is a clever musician, playing violin, piano and organ with unusual skill. The first intimation that many of Chaplin's friends and followers knew of this musical talent was the placing of an order for a Robert-Morton organ to be installed in his new [Beverly Hills] home in the course of construction. This is one of the finest, residences in the Hollywood district. In the music room provision was also made for an echo organ and a special roll device will also be installed on the instrument.

It is expected that Charlie will "shoulder arms" over the console of the new instrument when the Pipes of Pan are playing in the springtime.

Now one of the richest entertainers in the world, Chaplin was certainly enjoying and reveling to some degree in the spoils, which sent a mixed message to some fans and critics. In the September 2, 1922 Music Trade Review, Los Angeles music columnist Marshall Breeden made the observation that Chaplin had once "told this writer that in the early days of his stage life, and later in pictures, he strove to be artistic. He did not look only for the money. Now to him money comes, but he certainly is the one outstanding man in the world who comes closest to the border line between comedy and tragedy." In many ways those words were predictive as well.

Creativity and Chaos

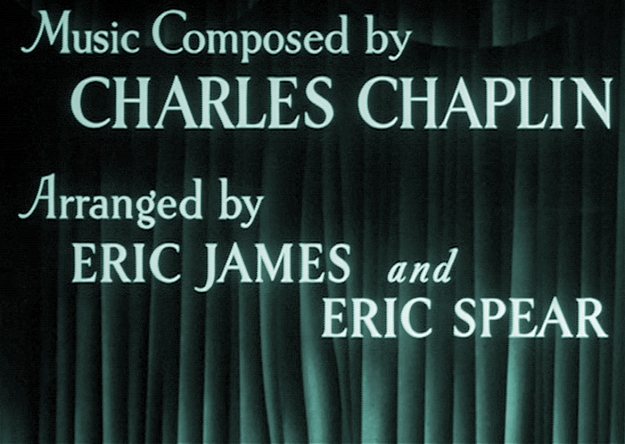

In 1923 Charlie was free from First National, and ready to start on his contract signed with his own collective company, United Artists. With ready financing, his own studio, and the support of many of his peers, he was finally afforded the freedom to make films on his terms and his schedule. It would take nineteen years for him to fulfill his eight film contract, but they included his four most notable masterpieces, all of which had scores by the director and star as well.

|

His first effort with UA in 1923 was A Woman of Paris. Unlike his previous films, this one was a romantic drama, not a comedy, and while it was written and directed by Chaplin, he only appeared in it for a few seconds. It was in part a vehicle for his long time leading lady and former romantic partner, Edna Purviance, to help her launch a dramatic career. But by this time Chaplin was already involved with other partners, including serial millionaire divorcée Peggy Hopkins Joyce who had inspired the film. While A Woman of Paris was received very well by the critics and his peers, the public did not seem to care for it very much, and it did poorly at the box office. There was no specific score known to exist when the film was first released, just the cue sheets. However, A Woman of Paris would be the very last film he would score at age 86, when he went into the studio with his arranger, Eric James, and tried to breathe new life into the movie with appropriate music.

There was again some trauma in his life while working on A Woman of Paris. After a number of affairs, he became involved with a Polish actress named Pola Negri. While he had managed to keep many of the earlier dalliances off the radar, the relationship with Negri, which allegedly included a one month engagement that was most likely contrived by the press, became quite public. Whether this was for publicity purposes or not has not been ascertained for certain, but many aspects of Pola's time in the United States clearly were dramatized for public consumption. At the same time that Mildred announced her intentions to remarry, she also lashed out at Charlie and Pola, calling their romance "funny," and that he would never the same after the "marital lessons I taught him." The stormy relationship ended after the engagement debacle, with Negri feigning major heartbreak.

This was followed by an alleged affair with actress Marion Davies, who was known to have been involved with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. In the end she stayed with Hearst, but their affair allegedly resurfaced a few times through the early 1930s. False stories have persisted concerning Chaplin and Davies, stating they were involved in the murder of Charlie's friend, film producer Thomas Ince, on Hearst's yacht on November 18, 1924, when Hearst mistook Ince for Chaplin and shot him a jealous rage. The supportable facts that put this falsehood are that the relationship between Chaplin and Davies is hard to pin down, Chaplin was confirmed to have not been on the yacht that weekend, and that Ince actually died from a heart ailment a day after being removed from the yacht with a case of acute indigestion. Chaplin's aid and chauffer Kono reportedly claimed that Ince was bleeding from a bullet wound to the head when he was brought off the yacht. The case was closed even before the persistent rumors took hold. It harmed Hearst's career, but not Chaplin's.

Chaplin's next film, one of the masterpieces, was inspired by the tales of the men who in the winter of 1897-1898 braved the cold and brutal Klondike, having scaled either Chilkoot Pass or White Pass into Canada with the hope of finding gold in the fields near Dawson several hundred miles downstream. The Gold Rush would start out with a legendary shot recreating the treacherous climb up Chilkoot Pass, filmed near Truckee in Northern California, and using a deft combination of comedy and pathos, told the story of a simple and unfortunate tramp miner who eventually earned his keep, even though he seemed to have lost the girl of his dreams.

having scaled either Chilkoot Pass or White Pass into Canada with the hope of finding gold in the fields near Dawson several hundred miles downstream. The Gold Rush would start out with a legendary shot recreating the treacherous climb up Chilkoot Pass, filmed near Truckee in Northern California, and using a deft combination of comedy and pathos, told the story of a simple and unfortunate tramp miner who eventually earned his keep, even though he seemed to have lost the girl of his dreams.

having scaled either Chilkoot Pass or White Pass into Canada with the hope of finding gold in the fields near Dawson several hundred miles downstream. The Gold Rush would start out with a legendary shot recreating the treacherous climb up Chilkoot Pass, filmed near Truckee in Northern California, and using a deft combination of comedy and pathos, told the story of a simple and unfortunate tramp miner who eventually earned his keep, even though he seemed to have lost the girl of his dreams.

having scaled either Chilkoot Pass or White Pass into Canada with the hope of finding gold in the fields near Dawson several hundred miles downstream. The Gold Rush would start out with a legendary shot recreating the treacherous climb up Chilkoot Pass, filmed near Truckee in Northern California, and using a deft combination of comedy and pathos, told the story of a simple and unfortunate tramp miner who eventually earned his keep, even though he seemed to have lost the girl of his dreams.Wanting even more control over the music involved with the film, Charlie actually did write some specific music for The Gold Rush, and in the midst of filming stopped long enough to visit a recording studio in May, 1925, and record two pieces, conducting Abe Lyman's Cocoanut Grove Orchestra from the Brunswick single. The session was reported on in the Music Trade Review of July 18, 1925:

Film Comedian an Able Left-Handed Violinist and Recently Conducted Orchestra in Making of Brunswick Record

Few of the admirers of Charlie Chaplin, the well-known film comedian, know that he is a composer or that he is much of a musician. As a matter of fact, however, he is quite accomplished in this direction He studied the violin in his youth and is one of the few left-handed bow-players the world has known. He is also a conductor as was demonstrated by his ability in directing Abe Lyman's Cocoanut Grove Orchestra when they recently made the recording of his new song "With You, Dear, In Bombay." This record was made for the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Co. Chaplin not only wielded the baton on this occasion but himself played the violin solo part of the recording.

It is said that the Brunswick Co. has inaugurated a special publicity department and will feature this Chaplin recording. "With You, Dear, In Bombay" is published by M. Witmark & Sons. Chaplin wrote both the words and music. It is a lively fox-trot with an appealing swing and very tuneful melody. The Witmark Co. will exploit the number on a wide scale.

Copies of the piece, which were included in the road show and big city premieres of the film, were available in the theater lobby. The cover featured a picture of Charlie standing in the snow in the elaborate Klondike town set constructed for the film at his studio.

The B-side of With You, Dear, In Bombay was Sing a Song co-written with and arranged by Gus Arnheim, but it was a forgettable tune. This music would be revisited in 1942 when The Gold Rush was scored for its sound re-release.

|

The chaos that had, for the most part, only mildly infiltrated the amorous comedian's life to that point, came to the forefront while filming The Gold Rush. While filming The Kid he had engaged a nearly 13-year-old girl named Lillita Louise MacMurray as an angel in a dream sequence, one in which ironically he had flirted with and kissed the girl. She came around looking for work, and Charlie decided to use her as the femme fatale for his new film. Now 16, and renamed as Lita Grey, Chaplin followed what had become a pattern and became romantically involved with the girl during the initial filming in 1924. The affair led to a pregnancy, which led to a more or less forced marriage, which led to shutting the production down while Chaplin dealt with this tenuous situation. Their union was a difficult one from the start, but they would stay together long enough not only for her to give birth to Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr., but also their second son Sydney Earle Chaplin soon after.

Chaplin had to scrap all the scenes with Lita and now employed an film extra who had recently arrived from Chicago, Georgia Hale. The pace of filming was no faster, even though the plot was changed very little during that period.

Even while Lita was pregnant with their second child, Chaplin started an affair with a willing Hale. Their relationship had a bittersweet ending that was later reflected in the sound re-release of the film in 1942, where the final scene with the two characters kissing was excised with a much less romantic shot of them walking into the background.

|

The Gold Rush was liked by virtually everybody who saw it, and it further established Chaplin as one of the best film makers of the era. It remains on the top lists of not only the American Film Institute but the Library of Congress and National Film Registry as well. However, there is a distinction to be made between the original and the 1942 re-release which Chaplin himself helped to score from certain selections, and composed some of the music as well. It is more often this version, with narration instead of inter-titles, which is the better preserved and more revered one, in part because of his direct musical involvement.

In addition to his original cues and songs (arranged by professionals but selected by the director), Chaplin liberally utilized Romanze, Opus 118, No. 5, by Johannes Brahms, the folk song Coming Through the Rye, portions of Flight of the Bumblebee by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and the main waltz theme from Sleeping Beauty by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Even though he did not compose all of the cues, these choices should not be dismissed as many film makers since that time have used similar classical pieces either as placeholders or suggestions to inform their hired composers, or in a stylized manner that suits their film, much as Chaplin did. It showed more than just an appreciation of classical music, going further to reinforce the actions or emotions on the screen with an underscore that was appropriate and not distracting. The few complaints about the 1942 release were more about the rapid-fire narration style of Chaplin than anything else.

After a short period of recovery, Chaplin purchased another reproducing piano, an Ampico, for his home in 1926. That same year he started on The Circus, a film based on love triangle themes that had been previously visited, most notably in his Mutual film The Vagabond. The making of this film was complicated by a legal battle that started with Lita filing for divorce from her famous husband. To the press she wailed that Charlie was starving her and his two sons, while in reality he was giving the lawyers checks, but they were rejected because they were not big enough. Charlie brought charges of defamation against Lita and her attorneys.

The battle became so intense that he had to stop production for nearly eight months while Charlie fought against a seizure of his studio as a marital asset. It was also beset by other issues, such as winds bringing down the main circus tent set, film exposures that proved to be unusable, and a fire that burned all of the standing sets and props.

|

At the end of the divorce ordeal both parties dropped their charges and reached an amicable settlement of around $825,000 to support young Charlie and Sydney. It also helped to temporarily get rid of the distraction from the press. However, just prior to the last day of shooting when they took the circus wagons out of town to a friendlier location, the wagons were stolen as part of a college student prank for use as a bonfire. There were other perils while shooting the film, such as Charlie doing stunts on a high wire, and inside a lions cage for a reported 200 takes with the unfriendly beasts. Their mother, Hannah, also died during the filming seven years after having been brought over to the United States. Charlie and Sydney housed her in relative comfort in Glendale, California, until her death. Several years afterwards the half-brothers found out that they had yet another half-brother through their mother, Wheeler Dryden, who had been raised by Charlie Sr.

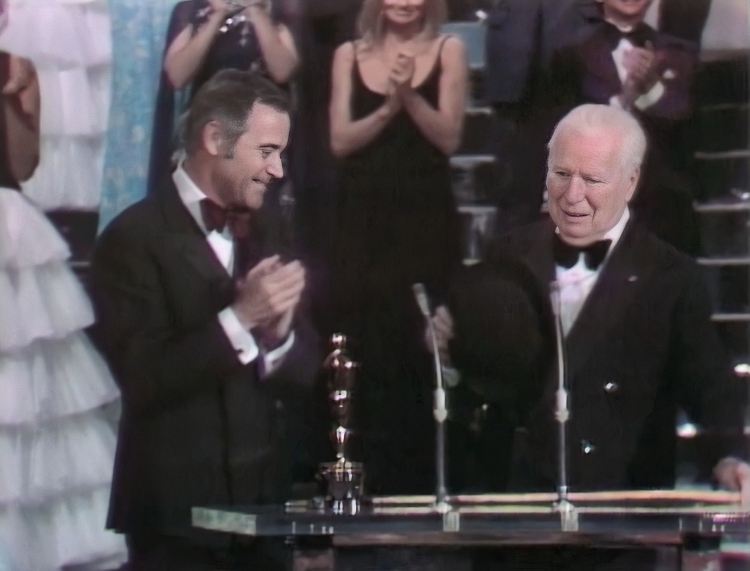

The Circus was warmly met by the public, and it was enough to earn him his first Academy Award at the very first Academy Award ceremony in 1929 (the term Oscar™ was not yet in use) for "Versatility and genius in writing, acting, directing and producing." He had originally been nominated in several categories, but the Academy instead decided to give him the uncontested special award instead. Had it been a sound film they likely would have had to add "composing," making Chaplin one of the only film stars in history to excel in all five categories (he would later win an Oscar™ for a film score and was considered for one for choreography as well). Chaplin's direct involvement with the work of his favorite and most tolerant cameraman, Rollie Totheroh, might have also brought a consideration for cinematography. When he dictated his biography in 1964, Charlie made only a passing mention the film in the book at all, perhaps because of its painful relationship with the nasty public divorce and his mother's last years.

In the 1930 census, Charles Jr. and Sydney were living with Lita's grandmother, Louise Curry, at 521 North Beverly Drive in Beverly Hills. Lita was listed as living next door at 523 North Beverly Drive. Both were comfortably well off, showing as owning their expensive homes, paid for, no doubt, by Charlie. He was residing at 1103 Cove Way in Beverly Hills, with four Japanese servants and the wife and two sons of one of them, Robert K. Sato. Friendly rival comic actor Buster Keaton, who was listed on the same page just above Chaplin, was living three blocks off on Hartford Way, but would be gone from that household within a year.

Coping with Sound and Soundtracks

For his next act, Charlie would embark on perhaps the most difficult film journey of his career that not only tested his creativity in every way, but his resolve and limited patience as well. Even before The Circus had been released, the entire landscape of the motion picture changed with the release of the Warner Brothers synchronized sound film The Jazz Singer in the late fall of 1927.

Even though most of the dialogue of that film used inter-titles, there was one scene in which star Al Jolson interacted live with his screen mother while playing Blue Skies which clearly showed the potential for sound. Other than Chaplin, Jolson was likely the biggest star in show business at that time, yet the public had seen much less of him since he was known for stage and sound recordings. Nearly overnight, however, many of Chaplin's previous efforts were overshadowed by the introduction of practical sound films.

|

Early conversion to sound was not inexpensive for theaters, and in order to accommodate both the synchronized discs of the Vitaphone system from Warner Brothers and the more practical sound on film system from Fox and Lee DeForest, even more equipment had to be installed. Yet by the end of 1928, with almost all of the major studios producing sound films in either format, more than half of the theaters in the United States had made the investment in one or the other system, or both, since that was what the ticket-buying public was crying for. By 1930 silent films would be all but gone.

For Chaplin this conversion presented a multiplicity of problems. For starters, his older films, most shot at an average of 18 frames per second, would not show correctly on the newer sound projectors which displayed films at 24 frames per second. Conversion of older films was costly, so the public soon accepted that silent films would simply look faster than sound films. He had often used undercranking of the film to his advantage to speed up certain portions, and would continue to, but the conversion of an entire film was a different matter.

The bigger problem was that the very thing that made him a star had the potential to be totally negated by sound. Chaplin was a pantomime artist. Many of his films used far less inter-titles than those of his peers, because the action was fairly obvious. Therefore, with only a little change in inter-titles to reflect the country of exhibition, his films did not need translation in any country. They were nearly as funny or moving in Hong Kong as they were in Paris, Berlin or St. Louis, Missouri. Spoken sound would immediately make each film an American or English language film. The use of dialog also negated some of the broad movements of pantomime, which would have been deemed overacting in conjunction with speech.

He was also clear, as were many critics, that sound film had its place as far as presenting musical numbers, but dialog had gotten by just fine with inter-titles for over two decades.

|

City Lights had already gone through several alterations during 1929 and into 1930, most of them for story points. Scenes were shot dozens or even hundreds of times in order to capture a subtlety or an angle, and most were discarded. In the background, Charlie was concerned about how well a silent film would play when the public was asking for sound. He did some experimental takes with sound for one or two days on a couple of dialog scenes, then abandoned that concept. In the end, Charlie proposed that the only difference between this film and his previous efforts was that there would be a unified score distributed with the film by way of a soundtrack. This was the culmination of what he had been trying to do since The Kid.

It was Chaplin himself who either composed or selected the pieces for the entire score of City Lights. He engaged Arthur Johnson and Alfred Newman to arrange and orchestrate his choices, but there was no question who was in charge of the overall execution of the music. While Chaplin was not well trained in Western notation or harmony and theory, he had an innate sense of the emotional and action aspects of the right music. Calling on one of his favorite composers, Richard Wagner, as well as accurately predicting virtually every film composer from Max Steiner (whose score for King Kong in 1933 is regarded as the first fully original film underscore) to John Williams, Charlie worked with specific musical motifs assigned to a character, location or incident.

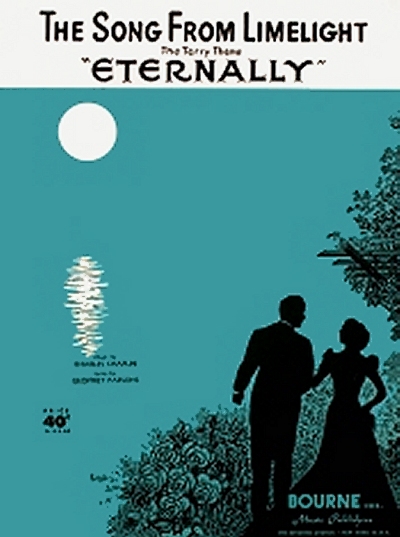

For the blind flower girl, played by the engaging but problematic Virginia Cherrill, he selected La Violetera (Who Will Buy My Violets) by José Padilla. Chaplin himself composed two other themes for her, one related to her simple but poor flat (apartment), and the other for emotional reflective close-ups. Additional musical devices composed by Chaplin include a fanfare which opens the film and is heard in a few places announcing another pending calamity, and a galop reminiscent of those of the 1890s or early 1900s for some of the action scenes. There is also a theme for his tramp character as he wanders through the lonely city, appropriately enough played on cello, although not by Chaplin himself. A faster theme played on the bassoon was used to accentuate his humorous moments.

Another predictive device was to substitute speaking with or through a saxophone for prattling dialog, similar to what would be used for adult speech in the Peanuts cartoons of the 1960s to 1990s. The rest of the cues were composed or cut to the action on the screen, also predictive of cartoon scoring of the late 1930s and beyond.

|

Chaplin did stray from his traditional background which included a healthy dose of classical and older popular music, and called on contemporary forms to keep the film current and vital. For a scene where he and the millionaire character played by Harry Myers go to some of the hotspots in town, a bustling jazz theme played by a smaller ensemble is used. It is contrasted with a Latin rhumba for a party at the millionaire's mansion. A dramatic motif was used in association with the suicide attempt of the millionaire, in addition to two different themes for his highly contrasting drunken and sober moods. A couple of other familiar themes were inserted as well; a snippet of Scheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov played in two different timbres, and the more common How Dry I Am often used by arrangers for scenes involving alcohol. Most of the sound effects were also done with instruments with the exception of, literally, bells and whistles.

While most films of the time were using underscore sparingly, often interspersed with on-screen musical numbers, the entire soundtrack for City Lights codified his abilities and instincts not only as a composer but as a competent score writer, which requires a different skill set. Musically he was able to clearly define comedy, pathos, wistfulness, whimsy, and even love. Everything from English music hall motifs and ragtime through classical, jazz and loosely defined tangos. Some of the themes from City Lights were also rescored and used in a clever fashion by director Attenborough in the 1992 film Chaplin.

There were many issues with the film, including the contentious relationship between the director and his co-star, Virginia Cherrill. He considered her an amateur in every way, and even fired her at one point. After a failed attempt at trying to fit Georgia Hale into the role, he brought Cherrill back to finish the film. After more than two years, City Lights was finally unveiled to a wary public in January, 1931. In spite of the lack of dialog and Chaplin's concerns about the public's reception, City Lights was an enormous financial success, just right for audiences in the deepening Great Depression who needed a heartwarming story that favored the poor over the rich. It was critically acclaimed as well, not only for the acting and writing, but for the effective use of music.

He was uncertain about how it was to be perceived by the public, now yearning for talkies. The first sneak preview to a half-full house did not go well. The Los Angeles premiere, where Charlie sat with the Einsteins, was interrupted in the middle by the manager who wanted to talk about his new theater. But Charlie was more worried about New York, which could make or break his valiant effort. He rented the 1150 seat George M. Cohan Theater on 42nd Street for $7,000 per week for eight weeks, paid to fit it for sound films, then set out to charge more ($0.50 to $1.00) for his showing than most other movie theaters in New York were doing. In the end, Chaplin's instincts won out, and they trumped most of the nearby theaters in terms of attendance and profits. City Lights, the semi-silent gamble, was a critical and public success, much needed after his failed marriage and faltering career.

Chaplin had reached a new zenith in the creative process of the cinema. It would be five years until he unveiled his next act, and something else quite new where his fans was concerned. However, the news mongers were able to find enough to keep him in the press, and Chaplin's sometimes unraveling life certainly gave them material.

New Horizons - The World Tour