|

Charles Leonidas "Lee" Cooke (September 3, 1891 to December 25, 1958) | |||

Known Compositions Known Compositions | |||

|

1910

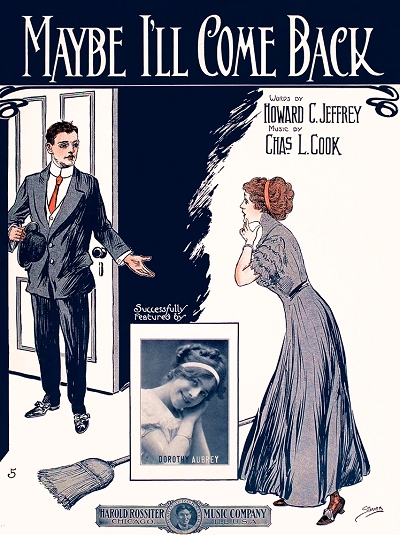

Maybe I'll Come Back [1]1912

Heroes of the Balkans: March Triumphant1913

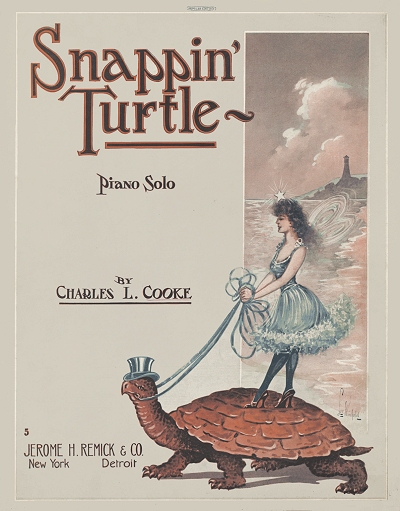

Snappin' Turtle1914

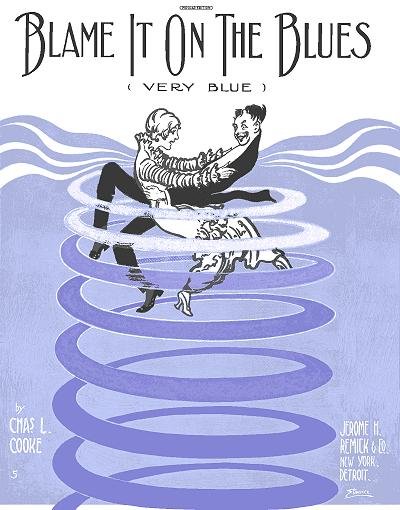

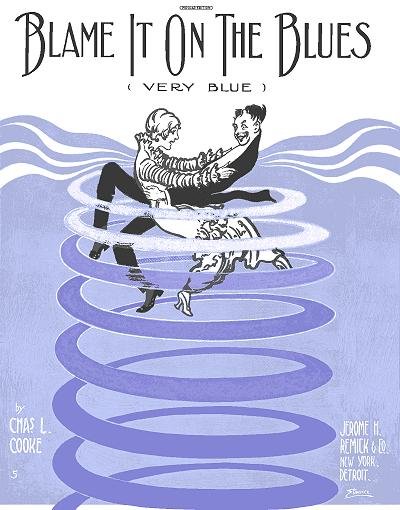

Blame It on the Blues (Very Blue)I Wonder Where My Lovin' Man Has Gone [2,3] 1915

Such is Life1916

Tom Brown's Trilling Tune: A RagBo-Peep [2,4] 1917

You're a Great Big Lonesome Baby [2,5]1918

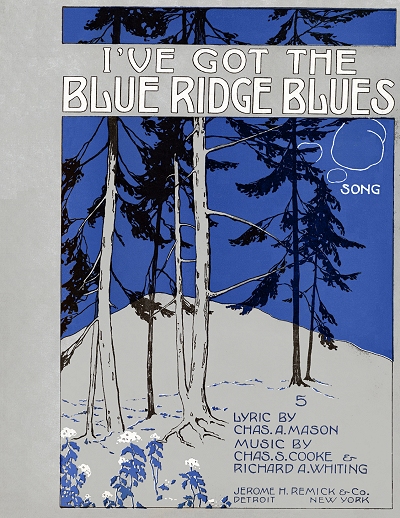

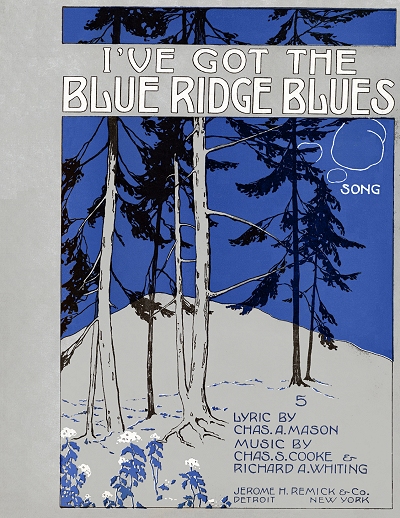

I've Got the Blue Ridge Blues [2,6]1921

Always in My Dreams [7]Goodbye Pretty Butterflies [7,8] Daisy Days [5,9] 1923

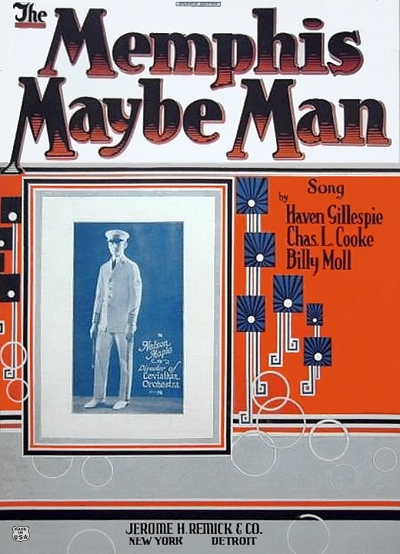

Weddin' Blues [10,11]The Girl of the Olden West [10,11] The Memphis Maybe Man [11,12] 1925

Do You Ever Dream of Me [13]Then Maybe I'll Come Back to You [14,15,16] Ho-Lo-E-Dee, O Lovie Answer Me [17] The Roses are Jealous of You [18] 1926

Pro Arte [Manuscript]Messin' Around [19] 1938

On the Banda Isles in the Banda SeaLazy Lute [Piano w/Clarinet or Tenor Saxophone] |

1940

Sing Song Swing1941

We Are Americans Too [20,21]1949

Blue Destiny: Fourth Movement [22,23]1951

The Big Stick Blues March [22]Sweetness [24] Gobble, Gobble, Gobble: Our Thanksgiving Turkey Song [25]

1. w/Howard C. Jeffrey

2. w/Richard A. Whiting 3. w/Earle C. Jones 4. w/Raymond B. Egan 5. w/Gus Kahn 6. w/Charles A. Mason 7. w/Jack Yellen 8. w/Abe Olman 9. w/Walter Blaufuss 10. w/Egbert A. Van Alstyne 11. w/Haven Gillespie 12. w/Billy Moll 13. w/Dave Goldye 14. w/William Dillon 15. w/Mike Costello 16. w/Dan De Julius 17. w/Fritz Zimmerman 18. w/C.J. Kennedy 19. w/Johnny St. Cyr 20. w/Eubie Blake 21. w/Andy Razaf 22. w/William Christopher Handy 23. w/Alberte Chiaffarelli 24. w/Bernie Grossman 25. w/George C. Noyes | ||

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |||

| |||

Known Broadway Show Arrangements Known Broadway Show Arrangements | |||

|

1930

Brown Buddies [111 Perf.]1932

Yeah Man [2 Perf.]1933

Shady Lady [30 Perf.]1939

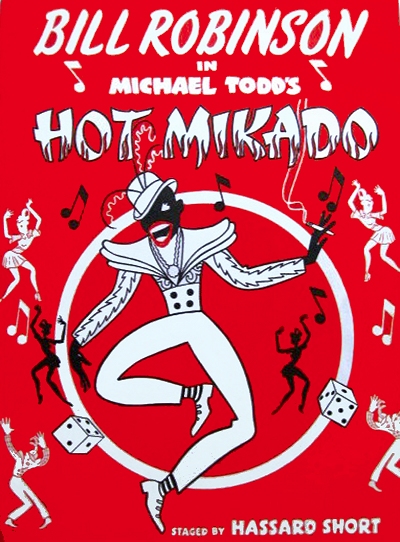

The Hot Mikado [85 Perf.]1940

John Henry [7 Perf.]All in Fun [3 Perf.] Cabin in the Sky [156 Perf.] 1941

Viva O'Brien [20 Perf.]Sons O' Fun [742 Perf] |

1942

Banjo Eyes [126 Perf.]1944

Follow the Girls [888 Perf.]1946

Three to Make Ready [327 Perf.]1950

Happy as Larry [3 Perf.]1952

Shuffle Along [4 Perf.]1954

The Boy Friend [485 Perf.] | ||

While there have been a number of essays published on Charles L. Cooke both on the web and in traditional print sources, many of them have had troubling variances between them on a number of facets of his life. An attempt has been made here to obtain the best possible verifiable information to construct a more accurate time line and account for at least the major milestones of his variegated life in music. While he was mostly forgotten at the time of his death in 1958, some of Cooke's tunes have remained popular in the ragtime and jazz worlds, and many more have been given new life. Hopefully this entry will help to do the same.

The first disagreement concerning Cooke's life was when it started. Many sources cite 1891, which is correct, but 1887 has also been given due to data on his WWI draft record and the 1920 census. The 1930 and 1940 censuses and his WWII draft record directly suggest 1891. What was not noted in these sources was the 1900 and 1910 enumerations, both of which clearly show him to be 9 and 19 respectively, with September of 1891 explicitly shown in 1900. Given the obvious difference between a 9-year-old and 13-year-old, it is unlikely his parents made such an error - twice, in fact. This matters as to his age when he started both his writing and musical careers, and where he was when these events happened, since they were sometimes reported by his age rather than the year. In this case, September 3, 1891, is clearly the firm date of birth, and will assumed for this essay.

What was not noted in these sources was the 1900 and 1910 enumerations, both of which clearly show him to be 9 and 19 respectively, with September of 1891 explicitly shown in 1900. Given the obvious difference between a 9-year-old and 13-year-old, it is unlikely his parents made such an error - twice, in fact. This matters as to his age when he started both his writing and musical careers, and where he was when these events happened, since they were sometimes reported by his age rather than the year. In this case, September 3, 1891, is clearly the firm date of birth, and will assumed for this essay.

What was not noted in these sources was the 1900 and 1910 enumerations, both of which clearly show him to be 9 and 19 respectively, with September of 1891 explicitly shown in 1900. Given the obvious difference between a 9-year-old and 13-year-old, it is unlikely his parents made such an error - twice, in fact. This matters as to his age when he started both his writing and musical careers, and where he was when these events happened, since they were sometimes reported by his age rather than the year. In this case, September 3, 1891, is clearly the firm date of birth, and will assumed for this essay.

What was not noted in these sources was the 1900 and 1910 enumerations, both of which clearly show him to be 9 and 19 respectively, with September of 1891 explicitly shown in 1900. Given the obvious difference between a 9-year-old and 13-year-old, it is unlikely his parents made such an error - twice, in fact. This matters as to his age when he started both his writing and musical careers, and where he was when these events happened, since they were sometimes reported by his age rather than the year. In this case, September 3, 1891, is clearly the firm date of birth, and will assumed for this essay.Charles was one of three children born in Louisville, Kentucky, to Charles Cooke (no definitive middle name or initial) and his wife Elizabeth "Hattie" Gains. One of the other children was Thelma Louise (6/1896), while another sibling died in infancy. The 1900 enumeration shows the family living in Louisville, with the elder Charles working as a "maker of fishing reels." At some point before 1910, Hattie died, leaving the elder Charles a widower. The 1910 census did not include Thelma, and her disposition was not ascertained from that record, but at fourteen she may have been living with another family member. It showed the elder Charles working in a tobacco factory, and the younger one, now 19, employed in the same place as a janitor. It is notable that many established sources claim that the Cookes were in Detroit, Michigan, before 1910, but the April census belies this. They probably relocated later in the year, and possibly even considered Chicago, Illinois, as a potential home as well, given what transpired before the year was out.

They probably relocated later in the year, and possibly even considered Chicago, Illinois, as a potential home as well, given what transpired before the year was out.

They probably relocated later in the year, and possibly even considered Chicago, Illinois, as a potential home as well, given what transpired before the year was out.

They probably relocated later in the year, and possibly even considered Chicago, Illinois, as a potential home as well, given what transpired before the year was out.Cooke later claimed to have been interested in music very early in his life, and having composed original pieces starting when he was eight-years-old, at the beginning of the ragtime era. He was educated in Louisville public schools, but given the family's circumstances, it seems unlikely that he received much in the way of individual professional music instruction. Yet his musical skills at the piano and his understanding of instrumentation allowed him to form an eight-piece band in Louisville around 1906 when he was fifteen, suggesting the possibility that he was mentored by one or more Louisville musicians in or out of the school system. Again, claims that he was working in bands in Detroit at age eighteen are contradicted by the 1910 census. However, possibly as early as late 1910, the Cookes had relocated to Detroit, Michigan, which appears to have been more favorable to them in the financial sense. Thelma moved with her father and brother, and would marry there in 1916 when she turned twenty.

Even before his presence was established in Detroit, 19-year-old Charles had his first tune published. It was a somewhat visceral comic number with lyrics by Howard C. Jeffrey, and found some popularity decades after it was issued. At that time, it may have been amusing for a man, obviously not a gentleman, to tell his lady, "I will come back when the elephants roost in the trees, I will come back, when the whales make love to bees, I will come back when the sun refuses to shine, and President Taft is a cousin of mine…" With slight lyrical alterations, it enjoyed later performances by Marlene Dietrich and Judy Garland. As the number, obviously intended for vaudeville performers, was published in Chicago by Harold Rossiter and copyrighted on December 30, 1910, it is possible that Charles put his toe in the water in that city to see how he might fare. However, he was soon becoming established as a musician in Detroit by 1911.

Among the first musical organizations that Charles worked for in his new home was the orchestra run by Fred St. Clair Stone, one of the main organizers of the powerful black musicians union in Detroit, most likely as a pianist, but possibly as a leader in training. This stint ended abruptly in early 1912 when Stone died as the result of a trolley car mishap. However, he was quickly absorbed into the organization run by Stone's primary rival, Benjamin Shook. In this group he also played piano, but began writing dance arrangements as well. There are reports that he had his own side group during the early-to-mid-1910s, Cookie and His Ginger Snaps, but this is hard to pin down. In any case, Cooke's first published work, Heroes of the Balkans, appeared in 1912 in Detroit, issued by the dominant house of Jerome H. Remick. It was closely followed by the piece Snappin' Turtle in 1913. In the interim, Charles was married to Canadian immigrant and fellow musician Lynthen Virginia Hyder on October 23, 1912. Their daughter Virginia Louise was born in either 1914 or 1915, as later records vary as to her actual age.

This stint ended abruptly in early 1912 when Stone died as the result of a trolley car mishap. However, he was quickly absorbed into the organization run by Stone's primary rival, Benjamin Shook. In this group he also played piano, but began writing dance arrangements as well. There are reports that he had his own side group during the early-to-mid-1910s, Cookie and His Ginger Snaps, but this is hard to pin down. In any case, Cooke's first published work, Heroes of the Balkans, appeared in 1912 in Detroit, issued by the dominant house of Jerome H. Remick. It was closely followed by the piece Snappin' Turtle in 1913. In the interim, Charles was married to Canadian immigrant and fellow musician Lynthen Virginia Hyder on October 23, 1912. Their daughter Virginia Louise was born in either 1914 or 1915, as later records vary as to her actual age.

This stint ended abruptly in early 1912 when Stone died as the result of a trolley car mishap. However, he was quickly absorbed into the organization run by Stone's primary rival, Benjamin Shook. In this group he also played piano, but began writing dance arrangements as well. There are reports that he had his own side group during the early-to-mid-1910s, Cookie and His Ginger Snaps, but this is hard to pin down. In any case, Cooke's first published work, Heroes of the Balkans, appeared in 1912 in Detroit, issued by the dominant house of Jerome H. Remick. It was closely followed by the piece Snappin' Turtle in 1913. In the interim, Charles was married to Canadian immigrant and fellow musician Lynthen Virginia Hyder on October 23, 1912. Their daughter Virginia Louise was born in either 1914 or 1915, as later records vary as to her actual age.

This stint ended abruptly in early 1912 when Stone died as the result of a trolley car mishap. However, he was quickly absorbed into the organization run by Stone's primary rival, Benjamin Shook. In this group he also played piano, but began writing dance arrangements as well. There are reports that he had his own side group during the early-to-mid-1910s, Cookie and His Ginger Snaps, but this is hard to pin down. In any case, Cooke's first published work, Heroes of the Balkans, appeared in 1912 in Detroit, issued by the dominant house of Jerome H. Remick. It was closely followed by the piece Snappin' Turtle in 1913. In the interim, Charles was married to Canadian immigrant and fellow musician Lynthen Virginia Hyder on October 23, 1912. Their daughter Virginia Louise was born in either 1914 or 1915, as later records vary as to her actual age.One of Cooke's more enduring compositions would appear in 1914. Blame It on the Blues is a very well thought-out piano rag that clearly sounds like an orchestral reduction in many regards. The syncopations are varied throughout, and the B-section demonstrates several aspects of popular dance band music, including melodic shifts and a two-bar break in the middle. The trio challenges both hands with cross-interaction, and while less lyrical in some regards is still memorable. It was a good seller for Remick, and nearly four decades later was revived during the 1950s, most notably by Barbary Coast pianist Paul Lingle. The piece was also heavily advertised by Remick in New York trad papers such as Variety, touting it as "A $5,000 Instrumental Number… Great for Dancers—Great for Dumb Acts—Great for Overtures." It was followed up with a fox-trot in 1915, Such is life, which sounds like a song title but was just an instrumental composition. Both pieces were soon made into player piano rolls.

Charles continued to work for the Shook organization throughout most of the rest of 1910s. His June 1917 draft record showed him as employed by Shook and playing at the Griswold Hotel in Detroit. It also included a physical description of Cooke as tall and slender, and showed that, possibly for reasons of simplicity, had shortened his middle name to Lee instead of Leonidas. He claimed his sole support of wife and child as a reason for deferment, and evidently was never called up. This record clearly contradicts claims found in some biographies that he had moved to Chicago in 1910. However, soon after, possibly by the end of 1917, Charles disengaged from residency with the Shook orchestra and finally did move west to Chicago, where he started leading his own groups.

He claimed his sole support of wife and child as a reason for deferment, and evidently was never called up. This record clearly contradicts claims found in some biographies that he had moved to Chicago in 1910. However, soon after, possibly by the end of 1917, Charles disengaged from residency with the Shook orchestra and finally did move west to Chicago, where he started leading his own groups.

He claimed his sole support of wife and child as a reason for deferment, and evidently was never called up. This record clearly contradicts claims found in some biographies that he had moved to Chicago in 1910. However, soon after, possibly by the end of 1917, Charles disengaged from residency with the Shook orchestra and finally did move west to Chicago, where he started leading his own groups.

He claimed his sole support of wife and child as a reason for deferment, and evidently was never called up. This record clearly contradicts claims found in some biographies that he had moved to Chicago in 1910. However, soon after, possibly by the end of 1917, Charles disengaged from residency with the Shook orchestra and finally did move west to Chicago, where he started leading his own groups.Among the first of those orchestras was for the dance hall at Riverview Park, a trolley or amusement park just north of the downtown area. Cooke was reportedly responsible for the contracting of all musicians who performed at the park, and would remain there for at least three years during the warmer times of year, playing at hotels or other dance halls during the winter months as per scant newspaper notices, and potentially some piano or organ solo gigs as well. That same year of 1918 saw another important publication titled I've Got the Blue Ridge Blues. Set to lyrics by Charles A. Mason and co-composed with well-known white composer Richard A. Whiting, it was issued by Jerome H. Remick in New York, who had been responsible for some of Cooke's earlier works. Somehow, through either a publisher or clerical error, he was attributed as Chas. S. Cooke, including in the initial copyright record. However, since he wrote other works with both gentlemen, it is clearly a simple misattribution. The song quickly got some traction, and was even adopted for a short while by Al Jolson as one of a flurry of interpretations into his stage show Sinbad at the Winter Garden Theater for the 1918-1919 season.

During his time at Riverview, Cooke began to attract the attention of music fans as well as skilled musicians, and some of them migrated to his orchestra from other Chicago area organizations. His work as a bandleader entailed creating a varied palette of fine arrangements,

but left little time for composition, so his output throughout the late 1910s and early 1920s was scant. The January 1920 enumeration showed him and his family in Chicago hosting three boarders, with Charles listed as a band musician. Curiously, however, Charles and Lynthen were married - again - in Toledo, Ohio, on May 10, 1920. Although a record exists for their 1912 marriage, and in spite of them having already had a child, Lynthen showed as not having been married before on the certificate. Given her origin as a Canadian, this may have had something to do with immigration status, but nothing appears to survive explaining this unusual move, including crossing state lines. By this time, Lynthen was no longer listed as a musician.

|

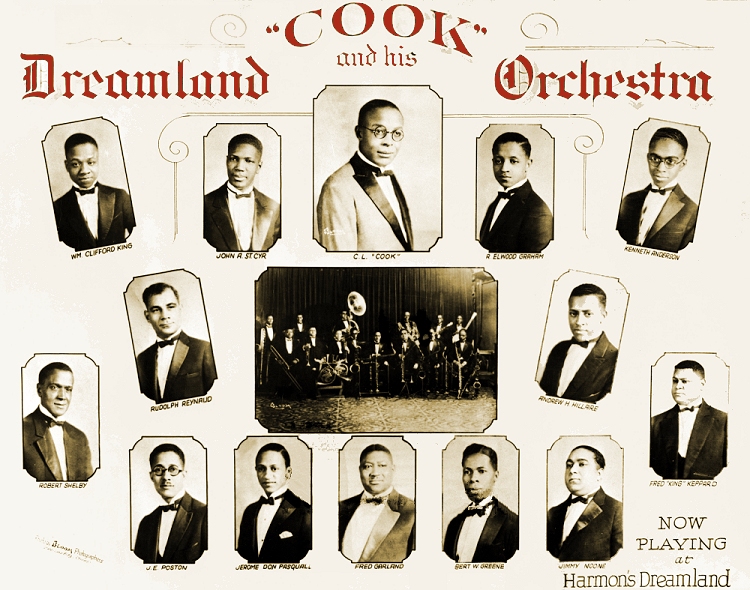

By the early 1920s, Cooke had an office in the State-Lake Building in downtown, and was not only doing musical contracting, but writing arrangements for orchestras in other theaters around town. He also started taking advanced music classes at the Chicago Musical College. The time line is a bit unclear on this, but he evidently graduated with a Bachelor of Music in 1922, later obtaining a Doctor of Music in 1926, both from the Chicago Musical College. [The Chicago College of Music is also mentioned in some later articles as an additional school he attended.] It was at this time, and perhaps even prior to it, that Charles acquired the nick name of "Doc" Cooke, which stuck with him throughout his career. In the interim, he took over the bandleader duties at Patrick "Paddy" Harmon's Dreamland Ballroom [and roller skating rink], located on the near west side at 1761 West Van Buren Street, with a 16-piece orchestra (although sizes varied over the years). Harmon would often lease the ballroom on the Municipal Pier during the summer months, and the group would often play there as well. Advertising often showed the group as "Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra," dropping the 'e' off his last name. This was also a back and forth variance that would continue for many years, with his name often spelled correctly on sheet music and official records, but usually as Cook in association with his orchestra. His notoriety was such that even in 1922 he was mentioned in advertising with other bands in The Billboard for featuring pieces in his repertoire, such as the popular Shreveport Blues.

Harmon would often lease the ballroom on the Municipal Pier during the summer months, and the group would often play there as well. Advertising often showed the group as "Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra," dropping the 'e' off his last name. This was also a back and forth variance that would continue for many years, with his name often spelled correctly on sheet music and official records, but usually as Cook in association with his orchestra. His notoriety was such that even in 1922 he was mentioned in advertising with other bands in The Billboard for featuring pieces in his repertoire, such as the popular Shreveport Blues.

Harmon would often lease the ballroom on the Municipal Pier during the summer months, and the group would often play there as well. Advertising often showed the group as "Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra," dropping the 'e' off his last name. This was also a back and forth variance that would continue for many years, with his name often spelled correctly on sheet music and official records, but usually as Cook in association with his orchestra. His notoriety was such that even in 1922 he was mentioned in advertising with other bands in The Billboard for featuring pieces in his repertoire, such as the popular Shreveport Blues.

Harmon would often lease the ballroom on the Municipal Pier during the summer months, and the group would often play there as well. Advertising often showed the group as "Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra," dropping the 'e' off his last name. This was also a back and forth variance that would continue for many years, with his name often spelled correctly on sheet music and official records, but usually as Cook in association with his orchestra. His notoriety was such that even in 1922 he was mentioned in advertising with other bands in The Billboard for featuring pieces in his repertoire, such as the popular Shreveport Blues.Among the more notable musicians that played in Cooke's group were banjoist Johnny St. Cyr, clarinetist Jimmy Noone, saxophonist Joe Poston, and, most notably, dynamic trumpet player Freddie Keppard. In fact, on both records and in advertising, Keppard was often featured alongside Cooke, given his star power. At a time when jazz was coming into its own in Chicago, Cooke's orchestra was in the forefront along with Joseph "King" Oliver and his Creole Band, and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, although Cooke's organization was a bit larger than theirs, and geared more towards ballroom dancing. He did, however, have smaller ensembles as well, which were comparable to the makeup of what are now considered traditional jazz bands. While Cooke had Keppard, Oliver had both himself and, for a while, Louis Armstrong, so history seems to have favored him just a bit more, perhaps in part because of their New Orleans roots which informed their style of playing.

Doc Cooke would, however, create his own legacy through a series of fine recordings made between 1924 and 1928. The first round were cut for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, where many other jazz pioneers such as Oliver, Armstrong, and "Jelly Roll" Morton had also recorded.Doc Cook and his Dreamland Orchestra cut six sides for Gennett in early 1924, taking what were likely the most popular or unique tunes from their repertoire, including one of Cooke's own compositions, The Memphis Maybe Man. It would be two and a half years before the group recorded again, this time in Chicago at the Columbia Records studios. That session would be followed two weeks later by his only sides for Okeh Records, this time reverting to an older band name, Cookie's Gingersnaps, comprised of a subset of the orchestra. There were three more sessions with Columbia in 1926, 1927 and 1928, all but one as Doc Cook and his 14 Doctors of Syncopation. It should be noted that Cooke was the conductor or bandleader on these sessions, and apparently did not play himself. While he played organ or piano at the ballroom, it is not entirely clear while he chose to not perform on the discs.

The first round were cut for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, where many other jazz pioneers such as Oliver, Armstrong, and "Jelly Roll" Morton had also recorded.Doc Cook and his Dreamland Orchestra cut six sides for Gennett in early 1924, taking what were likely the most popular or unique tunes from their repertoire, including one of Cooke's own compositions, The Memphis Maybe Man. It would be two and a half years before the group recorded again, this time in Chicago at the Columbia Records studios. That session would be followed two weeks later by his only sides for Okeh Records, this time reverting to an older band name, Cookie's Gingersnaps, comprised of a subset of the orchestra. There were three more sessions with Columbia in 1926, 1927 and 1928, all but one as Doc Cook and his 14 Doctors of Syncopation. It should be noted that Cooke was the conductor or bandleader on these sessions, and apparently did not play himself. While he played organ or piano at the ballroom, it is not entirely clear while he chose to not perform on the discs.

The first round were cut for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, where many other jazz pioneers such as Oliver, Armstrong, and "Jelly Roll" Morton had also recorded.Doc Cook and his Dreamland Orchestra cut six sides for Gennett in early 1924, taking what were likely the most popular or unique tunes from their repertoire, including one of Cooke's own compositions, The Memphis Maybe Man. It would be two and a half years before the group recorded again, this time in Chicago at the Columbia Records studios. That session would be followed two weeks later by his only sides for Okeh Records, this time reverting to an older band name, Cookie's Gingersnaps, comprised of a subset of the orchestra. There were three more sessions with Columbia in 1926, 1927 and 1928, all but one as Doc Cook and his 14 Doctors of Syncopation. It should be noted that Cooke was the conductor or bandleader on these sessions, and apparently did not play himself. While he played organ or piano at the ballroom, it is not entirely clear while he chose to not perform on the discs.

The first round were cut for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, where many other jazz pioneers such as Oliver, Armstrong, and "Jelly Roll" Morton had also recorded.Doc Cook and his Dreamland Orchestra cut six sides for Gennett in early 1924, taking what were likely the most popular or unique tunes from their repertoire, including one of Cooke's own compositions, The Memphis Maybe Man. It would be two and a half years before the group recorded again, this time in Chicago at the Columbia Records studios. That session would be followed two weeks later by his only sides for Okeh Records, this time reverting to an older band name, Cookie's Gingersnaps, comprised of a subset of the orchestra. There were three more sessions with Columbia in 1926, 1927 and 1928, all but one as Doc Cook and his 14 Doctors of Syncopation. It should be noted that Cooke was the conductor or bandleader on these sessions, and apparently did not play himself. While he played organ or piano at the ballroom, it is not entirely clear while he chose to not perform on the discs.The quantity of original Cooke compositions increased slightly from 1923 to 1925, but much of his publishing work was doing arrangements for Jerome H. Remick, Ted Browne, and other music houses. None of his own works from this period really became jazz or orchestra standards, as there was a glut of similar music issued at this same time on records, piano rolls, and sheet music,

with only a few hundred tunes rising to the top as perennial favorites. Whatever the reason, it appears that Charles stopped publishing in 1926, and it is possible his compositions were only heard on his last few records or at orchestra performances. In 1927 Cooke and his Doctors of Syncopation left Harmon's Dreamland for the Casino Dance Hall at the White City Amusement Park, located at 63rd and South Parkway. They also continued their partial residency at the ballroom on the Municipal Pier, which was renamed the Navy Pier in 1927, and did occasional concert and dance hall tours throughout the upper-Midwest.

|

The 1930 enumeration, taken on April 3, showed Cooke still residing in Chicago, listed as a dance hall musician. Lynthen and Virginia, on the other hand, were now back in Detroit, residing with a number of Lynthen's relatives, including nieces, a nephew, and two widowed aunts. As there was no apparent occupation shown for anybody in the household, and Lynthen showed as still married, it is possible that Charles was supporting them from Chicago. It is unclear when the move back to Detroit was made, but she would remain there throughout the remainder of her life. Charles, however, would not be in Chicago much longer. Many of his stars, including Noone and Keppard, had moved on, some leading groups of their own. Just a week after the enumeration, a notice in The Billboard of April 12 announced the beginning of their season, albeit on an abbreviated two night a week schedule, creating variety for the venue, but less work for each group:

In keeping with the policy of always adopting new ideas, the management of the White City ball rooms will introduce a different orchestra in the Casino each succeeding Wednesday, starting April 9. Doc Cook and his Doctors of Syncopation are the current attraction there. They will continue to play each Saturday and Sunday, including the Sunshine Matinees on Sunday afternoons…

In an unfortunate incident that fall in late November, what was left of the orchestra came back from a break one evening during a multi-week dance marathon held at the Chicago Coliseum, only to find that their instruments, which represented their livelihood, had all been stolen. As it was the beginning of the Great Depression and they were already working a reduced schedule in competition with other groups,

their probability of continuing regular employment as black musicians was already endangered. To make things worse, the promoter had failed to pay rent for the dance hall, and the event was canceled in progress. This was a major blow, and it resulted in the dissolution of the Doctors of Syncopation. Now that it was every man for himself, Cooke chose to relocate where the slim prospects were just a bit more in his favor. For Cook, however, he already had his foot in the door of his next home of opportunity, New York City.

|

Charles already had several connections and opportunities in New York, in part because of his continuing association with Jerome H. Remick, although they had been sold to a Hollywood studio by that time, and in part due to his friendship with several New York composers, musicians and producers. He had already created an orchestration for the musical Brown Buddies with a book by Carl Rickman and music by Joe Jordan and many others. Starring Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, it was enough of a success in the fall of 1930 and during a subsequent tour in 1931 that Cooke was instantly in demand for his snappy and effective arrangements. The next show in 1932, the revue Yeah Man was a victim of the Depression and a weak cast, lasting only 2 performances. Living in Manhattan since late 1930, Cooke became a fixture with the Crescendo Club, a successor of sorts to the pioneering Clef Club of the ragtime era. He also arranged works both for dance orchestras around town and for Broadway. There is also a question of whether or not he was still composing his own works, but simply not publishing them, and if he may have still recorded or conducted recordings. One clue to the latter which raises this question was seen in The Billboard o July 7, 1934:

Doc Cook and his Recording Orchestra are working thru New Jersey. Combo is booked to play the Whitehouse (N.J.) dance carnival in August and then are scheduled to tour North and South Dakota, Iowa, Oklahoma and Texas.

While no recordings under his name appear to exist past 1928, it is possible that his group served as a backup for singers or solo instrumentalists for sessions now and then, and perhaps even for radio, although the latter was limited for all but a few black musicians. Among those that Cooke became a confidant of and eventually an assistant to in the mid-1930s was the inimitable W.C. Handy. Now in his 60s, Handy was losing his vision, but not his drive. Cooke took over some the arranging duties for Handy's publishing firm during this period. In October of 1939, Handy arranged for the second in a series of concerts given by ASCAP at Carnegie Hall. The October 2 performance was reviewed positively by many papers, including the New York Sun:

As an amiable gesture of fraternity, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers last night turned over the conduct of the second concert of its series in Carnegie Hall to the Negro musicians of its membership. Thus, in one evening was reviewed the range of inclusiveness that is characteristic of the whole organization, for the program began with serious symphonic works by William Grant Still, Dr. Charles L. Cooke and James P. Johnson, programmed to examples of minstrelsy by Clarence Williams, Will Marion Cook and Shelton Brooks, and concluded on the high note of Louis Armstrong's trumpet.

Dr. Cooke's "Sketches of the Deep South" were both more conservative and less vertebrate in structure. There was a provision for spirituals in this section (several of them curiously noted as being "by" Harry T. Burleigh and Nathaniel Dett, who presumably merely arranged them) and much warm-timbered singing by the Abyssinian Choir and the Juanita Hall ensemble.

[There was an] informal minstrel show by the Crescendo Club, made up of Harlem's most prominent composers. [Also in attendance were Louis Armstrong, Claude Hopkins, Cab Calloway and their orchestras] who re-affirmed the Negro's preeminence in the field of contemporary jazz. The hall was crowded.

Fittingly the evening ended with a rendition of Handy's famed St. Louis Blues. Of note, neither Joe Jordan or Cooke, both part of the event, yet members of ASCAP, but their inclusion was a harbinger of the obvious. In 1940, Cooke was granted membership in that important musical organization.

Fittingly the evening ended with a rendition of Handy's famed St. Louis Blues. Of note, neither Joe Jordan or Cooke, both part of the event, yet members of ASCAP, but their inclusion was a harbinger of the obvious. In 1940, Cooke was granted membership in that important musical organization.Just prior to the Carnegie Hall event, Charles had made another splash on Broadway with a rearrangement of the Gilbert and Sullivan classic operetta, The Mikado. His version was titled The Hot Mikado, starring Bill Robinson and a cast of 150, and produced by no less than Michael Todd. After originating on Broadway in March of 1939, it toured through part of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic into 1940, with Cooke holding the baton for at least part of the run. This was followed by the drama John Henry and the musical revue All In Fun, both in 1940, orchestrated and conducted by Cooke, albeit both for very short runs. The 1940 census showed him living in Manhattan and working as a music arranger in a music store, most likely Handy's. Meanwhile, in Detroit, Lynthen was still showing as married to Charles, living with some family members as the head of household, and again with no occupation. The state of their marriage was something not publicly found, but it may have been a continuing arrangement of some kind with support given by Charles. Lynthen was difficult to locate after 1940, but as Cooke's obituary stated he had left a widow behind, and no other marriages were found, it is probable that they stayed married through the end of his life.

In addition to his Broadway and concert work, Cooke was also providing arrangements for Radio City Music Hall, and even conducting now and then. He also reportedly held an executive post with the RKO organization in some capacity, perhaps for some of their New York theaters, but in what capacity is unclear. There are no IMDB listings for him as either a composer or arranger, so it was likely not for films, at least in a credited capacity. Cooke was also an active member of the Negro Actors Guild, Musicians Local 802, and eventually the W.C. Handy Foundation for the Blind.

so it was likely not for films, at least in a credited capacity. Cooke was also an active member of the Negro Actors Guild, Musicians Local 802, and eventually the W.C. Handy Foundation for the Blind.

so it was likely not for films, at least in a credited capacity. Cooke was also an active member of the Negro Actors Guild, Musicians Local 802, and eventually the W.C. Handy Foundation for the Blind.

so it was likely not for films, at least in a credited capacity. Cooke was also an active member of the Negro Actors Guild, Musicians Local 802, and eventually the W.C. Handy Foundation for the Blind.One of Charles' more important works on the cusp of World War II was co-written with well-known composers Eubie Blake and Andy Razaf, both quite active in the New York music scene. It was titled We are Americans Too, and acording to a syndicated article from May 1941, it was "inspired by the series of articles under that head in New York's precedent-smashing P.M and published by Handy Brothers (W.C.) Music Co., Inc." For Harold Robbins Music Charles produced a Choral Collection of Negro Spirituals for Mixed Voices in 1942. For Miller Music he did arranged a folio of popular Hawaiian songs for S.A.T.B. in 1944. There was also another Broadway success during war. Cooke provided many of the orchestrations for the hit show Sons o' Fun at the Winter Garden Theater in 1941, which ran for over two years, and for Banjo Eyes starring veteran performer Eddie Cantor, which ran for several months in 1942. These were followed up by contributions to Follow the Girls in 1944 which ran over two years. Later, in 1946, he both provided orchestrations for and conducted the revue Three to Make Ready starring Ray Bolger, which ran for the better part of a year on Broadway. So Charles was clearly remaining active in musical circles even as he was approaching his 60th year. However, by the late 1940s he had left Manhattan for a residence in Wurtsboro, New York, roughly an hour northwest of the city.

The 1950s were at least three decades removed from the ragtime that Cooke had grown up with, then outgrown in many respects. Yet at the same time there was a popular revival of the music of the 1910s and 1920s, although in a stylized nostalgic manner that was not an accurate reflection of the original. Still, there were artists who tried to present it as it was. Cooke's expertise was called in 1952 for two projects that harkened back to this era. For one, he ably assisted W.C. Handy for a record album that served as an audio biography of his life.

Handy was pretty much blind by this point, but still narrated the album, singing and playing the guitar throughout. Cooke arranged orchestrations for the effort, and played piano as well, accompanying the New York Choral Ensemble under Dr. Karl Adler for the project. That same year he helped Eubie Blake retool his pioneering 1921 show Shuffle Along for what became a disappointing four show run.

|

At age 62, Cooke decided to go into the music publishing business, however briefly, as announced in the Pittsburgh Courier of December 20, 1953:

Tackling the complicated and lucrative business of music publishing, a new firm of three highly competent music men has set itself up smack in the heart of Broadway. Known as MWC Associates and operating two firms Rae, Cox & Cooke and Enrica Music, the outfit has opened its doors to all persons concerned with all phases of music.

Teddy McRae, Eddie Wilcox and Dr. Charles L. Cooke are three of Tin Pan Alley's most respected musicians. All are members of ASCAP in high standing. Their offices are located at 1697 Broadway, near 53rd St.

This may have been in association with his latest and one of his last musical efforts, which was completed under trying circumstances. Charles had been contracted to provide orchestrations for the American adaptation of the recent British stage hit, The Boy Friend. There is little doubt that his acumen with dealing of music of the 1920s and in the style of that era helped to land him this lucrative job. When it debuted on Broadway the show was an instant hit, running well over a year. The Pittsburgh Courier of October 16, 1954, highlights the challenges that Cooke was experiencing at this juncture in his life:

There seems to be nearly as much talk about the orchestrations as the songs and dances in Broadway's latest musical hit, "The Boy Friend." Credit for dreaming up the "roaring twenties" sounds, complete with ukes, banjoes, wailing saxes and tinkling triangles goes to Charles L. Cooke and Ted Royal.

For Cooke this latest success comes after a painful year in which, as a result of a stroke, he has been paralyzed. Formerly right-handed, the talented musician has had to learn to do his music-making left-handed..

The effects of the stroke lingered throughout the next few years, and after the success of The Boy Friend, virtually nothing else was heard from or about Cooke. He died at his Wurtsboro home on Christmas Day, December 25, 1958, the result of another stroke. Aside from his obituary and the usual ASCAP announcement in the death notices, there was virtually nothing said in remembrance of him until the 1970s and the second revival of ragtime and traditional jazz. The recordings of Cooke's orchestras eventually made it to vinyl, and then digital formats, and his tunes, particularly Blame It on the Blues, have been and are still played at copious festivals featuring this type of music. His importance as a trained and educated musician and his contributions to American music should not be forgotten, and should be recognized as those of a talented individual, not just as a skilled musician of color. That he was regarded as an equal by many of his white peers speaks loudly as to his universal appeal and tacit refusal to be shunned because of his race. That he also proudly stood up for and embraced his race amidst all the difficulties faced by blacks in the business of music should further elevate the historical status of the talented Doctor Cooke.

This biography was culled largely from newspaper articles, album liner notes, and the usual assemblage of government records. Given the challenges it makes to other Charles L. Cooke web and print biographies, particularly in scope of information and the time line, I will gladly endeavor to point anybody interested to sources of most of what is in the article, which is also cited inline.