Many aspects of the life of "Cow Cow" Davenport have either been lost to time or altered/enhanced to some degree by selective memory and speculation, so we will likely never know the whole story. However, it can also be clarified to some degree to present a more accurate representation on who he was and what his actual contributions to the music world were. This essay looks to correct some previous reporting on aspects of his life and clarify others of one of the originators of the boogie-woogie piano style, albeit more of a blues performer overall.

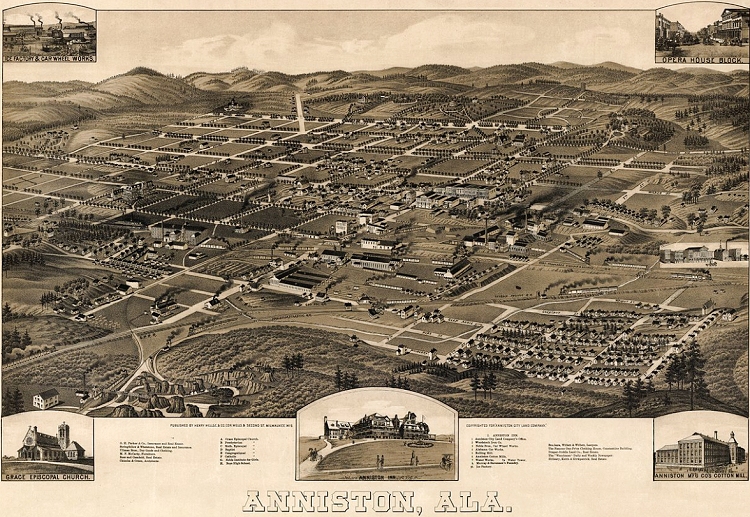

He was born Charles Edward Davenport in Anniston, Alabama, to Clem Davenport and his wife Queen Cary. Charles' other siblings included Annie (9/1886), Rosa L. (12/1889), Martha L. (9/1895), Mary Jane (5/1898), Queen V. (3/1900), Gertrude P. (1902) and Louis J. (9/1904).

Two others did not survive their first few years of life. While the traditional birth year for Charles has been shown as 1894, as per his World War II Draft Record, the 1900 enumeration shows a specific month and year of April, 1891. In addition, the 1910 enumeration suggests 1892, as do selected other documents and multiple obituaries published in December of 1955, citing his age as 63 at the time of death, collectively pointing to 1892. While it is rare that a parent will get the age of one of their children wrong before they are ten, it is possible. That given, either 1891 or 1892 will be an accepted year of birth for this essay, and 1894 will be dismissed given clear evidence to the contrary.

|

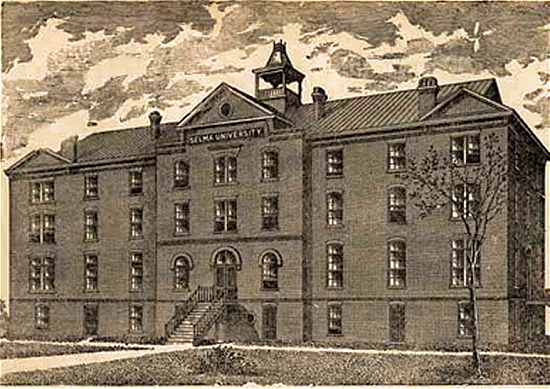

Times have historically been known to be difficult for black families in Alabama in the 1890s and early 1900s. However, Clem managed to get by, supporting his large brood working as a delivery man for a retail grocery store, and Queen took in laundry at their home, as per the 1900 and 1910 enumerations. By 1910, Annie was working as a public-school teacher, and Charlie, now around 18, as a laborer in what appears to have been a pipefitters shop (the listing is difficult to read). By this time, Charles had reportedly been playing the keys for several years, having first learned on a church organ from his mother who played for their church, and then on a piano. He focused on popular works and styles of the time, mainly ragtime in a Southern style. Clem evidently had objections to his son leaning in this direction, hoping instead that he might become a man of the cloth. He sent his son off to Selma University from 1910 into 1911, a Baptist college and theological seminary. This move might be questioned due to the family's financial status, but the school may have been reasonably priced or subsidized by the church, so his attendance there remains a probability. Charles' time at the seminary was short because of his propensity to play the piano a bit too "freely" at one or more formal functions. In his own words from The Jazz Record of December, 1944, Davenport stated that:

|

At that school I could play piano like I wanted to… I'd get invitations to all the socials, and I would play. At that time they didn't allow them to dance, but they would march up a breeze. [Note that a Cakewalk can be regarded as a march of some kind since it is stepped in rhythm on the beat.] Quite naturally with my old ragtime playing, when they'd get to corners they'd kind of shake themselves.

He also said that "the girls got so frisky they couldn't march in time." This incident, perhaps more than one of them, resulted in his expulsion from the school, and as per Davenport himself, became the inspiration for the well-known tune Mama Don't Allow It. (The true authorship of this song has also been challenged over the decades, and may actually have been adapted by W.C. Handy. Davenport recorded and possibly wrote Mama Don't Allow No Easy Riders Around Here, which may be some of the cause of the confusion.)

The style of playing that Davenport, mostly self-taught, was working out would eventually morph into one of many flavors of what would called "boogie woogie." It seems to have started out as "boogie," which is a reference to the "bogeyman" or "boogerman," an export from England and Europe representing the devil or a bad spirt who would visit naughty children and scare them out of bad behavior. Charles claimed that he dubbed his playing style and compositions as "boogie music," which reflected pretty much anything played in "joints where nice people did not go." The "woogie" was more or less a rhyming add on that helped to match the moniker to the basic rhythm of the style. Whether it was Charles who actually coined the name or not is unclear, as there are others who have made or simply earned that same claim, including brothers Hersal Thomas and George W. Thomas of Arkansas who had even published pieces of this nature by the early 1920s. The bass line of at least one boogie style was already known even before that, having appeared in print in Weary Blues by composer/arranger Artie Matthews in 1915. So even though Davenport may have had a bit more of a solid claim on this than "Jelly Roll" Morton did concerning the invention of jazz, it nonetheless remains a claim that is somewhat up for grabs.

Accounts of the next several years are vague. It is unclear if Charles was allowed back into his home, but it does appear he stayed in Alabama throughout much of the 1910s, probably not far from Anniston. In the Jazz Record interview he recounted at least part of this time as a learning experience:

So I drifted to Birmingham… There I was first hired as a piano player, in a place down on 18th Street. Then I began to hear other people play. There weren't so many competitors at that time. By me not knowing [how to read] music I had to make up the stuff to play. The others would get interested in me and gang around the piano.

Another account from Frank Harriott in Ebony Magazine of July, 1950, put in him in Atlanta, which may not be as likely as Birmingham, but possible. He recounted that Davenport was playing in honky tonks and backrooms of bars in the Black Bottom district, which was largely comprised of saloons and houses of prostitution. He also reportedly worked in a brothel for a few dollars a week plus room and board. This was accompanied by a claim that he was "scared of sporting women," and therefore did not get involved with them. Claims that he also worked in Storyville brothels in New Orleans are suspect at best, considering they were closed in 1917, and given his known travel and geography, might be dismissed as a misinterpretation of his time in Birmingham. Charles evidently went back to Anniston for a while, as noted on his June 5, 1917 draft record. It showed that he was working for his mother, Queen, at a restaurant she was running at the time, employed as a musician. It also showed (the writing is not clear) the presence of a wife and possibly a child. It is not clear who this was as his first known wife did not fit in this time line, so it may remain a mystery union, or a contrived reason to seek a deference from the draft.

Charles' first job in vaudeville came about around 1918 in Augusta, Georgia, where he played in a theater for films as well as dancers and interludes between acts. Among those he claimed to work with were Gertrude Williams and Bessie Smith, the latter who was just beginning what would be a tumultuous singing career, and that they stayed in the same boarding house at the rear of the theater. There is also mention of his working in Haeg's Circus in Macon, Georgia, as a blackface minstrel.

It is clear that Davenport worked for more than a year, possibly two, in a carnival and refined his entertainment skills while he was engaged there. But accounts that he did this shortly after leaving the Seminary are inaccurate.

The most likely time period for him traveling with the carnival of Lebanese immigrant Khalil G. Barkoot would be perhaps late 1918 or 1919 into perhaps 1921. It was a large show that had been established decades prior, and they even had their own special train in which to travel around the Eastern United States. Despite the public image of carnivals by that time, a writer for the Wheeling [West Virginia] Intelligencer gave them a somewhat dramatic promotion in a May 25, 1922 notice:

|

![K.G. Barkoot Carnival advertisement from June, 1922, Wheeling [West Virginia] Intelligencer barkoot carnival advertisement from june, 1922](/images/barkoot_ad.gif)

A few years ago, it will be remembered, carnivals were not on a very high plane, and shows of a suggestive nature were the features. "It appeared that a Moses was needed to lead the carnival men out of the wilderness, and it was K. G. Barkoot who undertook the task and pointed the way, and the same K. G. Barkoot has reaped the harvest of public confidence, and with this tangible asset has gone onward and upward the past twenty-three years to phenomenal success…" said James Bane… who saw the Barkoot shows recently in an Ohio city.

A show of this nature, with its shows and riding devices, furnishes pleasure to the entire family. They can enjoy the band concert and free attractions even if they do not spend a dime in the "Joy Zone."

Charles' participation in this show was clearly of benefit as it gave a wider public exposure to his persona and music, as well as the converse of him experiencing the world through his work on the stage. He was briefly mentored by pianist Bob Davis, who had got him the job with Barkoot. However, at one point he felt somewhat threatened when a 'real' piano player came into the organization, and he started to depend on some of his other talents to retain his position with the show. According to the account Jazz Record of December, 1944:

[Bob Davis] was the first man who ever showed me one key to the other, [such as] a-flat to c-sharp. Before that I didn't know but one key, and they called me a one-key piano player… I could always play for myself but couldn't play for anybody else. Quite naturally with women I had to learn different keys. He'd sit down and hum the show over to me and the different keys to girls to sing in. That was a great day's work for me, to learn to play in those different keys.

At that time it wasn't very many people knew music, so when they found another piano player that was the end of me. They din't like to fire me because I'd been with them. But I could sing, so I got on stage, started to sing my own songs. And I began to write songs I wanted to sing. These conditions in the south caused me to write the Jim Crow Blues."

Thus Davenport started to pursue a career as an entertainer. Either when he was still with Barkoot or shortly thereafter, around 1921 to 1922, he was married to blues singer and pianist Helen Rivers, but since official records were not located, it is hard to place this accurately in his time line. They were married for around a year before she left to pursue her own life and career. According to Charles in later years, he took it rather hard, but it may have inspired his signature piece. Even if there is an exaggeration in this, it makes for a story representative of his process:

I was so blue I commenced to get drunk. I went from honky tonk to honky tonk drinking everything I could get my hands on. When I walked out on stage that night I could hardly stand up straight. But I had sense enough to pretend like it was part of the act. I made up some words right there on the spot and began to sing my sadness:

Lord I woke up this morning, my gal was gone;

Fell out my bedside, hung my head and moaned.

Went down to State and I couldn't be satisfied;

I had those Railroad Blues, but I just too mean to cry.

In its original incarnation this song was the Railroad Blues, despite the fact that there were several pieces by this name in the early-to-mid-1920s. Likely composed between 1923 and 1925, this piece soon morphed into a more evolved song and instrumental boogie tune with a new name, as per a quote from the New York Daily News, June 4, 1942:

Cow Cow got his name while writing a blues song, part of which described a switchman boarding a train from the cowcatcher. "The word 'cow' seemed to stick in my mind… One night in a theater I ended a song with 'Nobody here can do what papa-cow cow-can do.' When the audience wanted to get acquainted with me after the show, they addressed me as 'Papa Cow Cow.' From then on ever since I have been called such a moniker."

Virtually immediately, Charles became the much more memorable Cow Cow Davenport, and he used that name professionally, as well as often in his personal life. This gave him a unique identity, and perhaps also some expectations of what could be expected from a growing crowd of quoted-name performers of the 1920s. Soon after leaving Barkoot, and this his failed marriage, Davenport joined the black-centric Theater Owners Booking Association, commonly known as TOBA. They provided a sort of union and booking outlet for black performers on a limited but effective vaudeville-type of circuit around the East and Midwest. Some of this work spilled into other vaudeville circuits as well, which translated into a variegated learning experience for the pianist, and exposure to other musicians, especially in the important center of publishing, New York City.

Charles met rising and moderately talented blues singer Dora Carr either during a stint in Macon, Georgia, or possibly while they were on the TOBA circuit (accounts vary on this).

She quickly latched on to him, reportedly to the point of repeated insistence that he be her pianist, and perhaps more. By inference and vague accounts, they possibly had a romantic relationship as well, although not one that resulted in another marriage for Davenport. Charles further claimed that he wanted to learn to sing better, so he derived some extra benefit from their relationship. From 1923 to perhaps 1926, he was Dora's primary accompanist and singing partner, and with a couple of other musicians they formed the TOBA act Davenport & Company. They mostly did comedy numbers and some blues songs on the circuit. Charles and Dora either left or were laid off from the tour in mid-1923 in New Orleans (in 1944, Davenport stated "We laid off in New Orleans," so the reason is vague). While playing there for a while, they met OKeh record producer and talent scout Ralph S. Peer who had been engaged in the remote recording of rural musicians in the South since June of 1923. He recommended that the couple make their way to Manhattan and engage in both recording and performance there.

|

It was in either in New Orleans or New York City that Davenport became acquainted with successful black composer and publisher Clarence Williams, possibly through his former partner Armand Piron who was still active in the Crescent City. Despite some questionable claims to having co-written songs he merely published, Williams still did a great service to black musicians in music of that time. With Davenport he co-wrote and published at least one song, You Might P'izen [Poison] Me, in 1924. It was recorded by OKeh Records in late January of that year, albeit with Williams at the piano, accompanying the singing of Davenport and Carr. Another Davenport composition, [Hurry and] Bring It On Home Blues, found its way to the B-side, with Williams again on the keys based on the laid-back playing style. (Although some sources credit the playing to Davenport, existing data and the style of performance indicate otherwise.)

What happened to Cow Cow and Dora over the next nineteen to twenty months is unclear, but they likely rejoined TOBA or another vaudeville circuit touring the Midwest, and possibly did some stints in New York. Davenport stayed in touch with Williams, who may have been peripherally responsible for getting him a 1925 date with Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, where many fine black musicians had preceded him over the past few years. He cut What It Takes and likely one or two more sides, but they remained unissued. One potential reason is that he may have had a signed a contract with OKeh, but this is difficult to confirm. He also recorded, or at least provided an editable template for both Cow Cow Blues and Hurry and Bring it On Home Blues for the Vocalstyle player piano roll company, recorded or issued late in the year. He claimed that he carted many of the rolls from store to store to promoted and sell them, but encountered resistance because "they didn't know what it was all about."

One potential reason is that he may have had a signed a contract with OKeh, but this is difficult to confirm. He also recorded, or at least provided an editable template for both Cow Cow Blues and Hurry and Bring it On Home Blues for the Vocalstyle player piano roll company, recorded or issued late in the year. He claimed that he carted many of the rolls from store to store to promoted and sell them, but encountered resistance because "they didn't know what it was all about."

One potential reason is that he may have had a signed a contract with OKeh, but this is difficult to confirm. He also recorded, or at least provided an editable template for both Cow Cow Blues and Hurry and Bring it On Home Blues for the Vocalstyle player piano roll company, recorded or issued late in the year. He claimed that he carted many of the rolls from store to store to promoted and sell them, but encountered resistance because "they didn't know what it was all about."

One potential reason is that he may have had a signed a contract with OKeh, but this is difficult to confirm. He also recorded, or at least provided an editable template for both Cow Cow Blues and Hurry and Bring it On Home Blues for the Vocalstyle player piano roll company, recorded or issued late in the year. He claimed that he carted many of the rolls from store to store to promoted and sell them, but encountered resistance because "they didn't know what it was all about."Cow Cow and Dora were back in the OKeh studio in October, 1925, and this time Williams, who had some control over the situation, sanctioned Davenport to play for the tracks. The October 1, 1925 session resulted in four sides. On Good woman's Blues, Black Girl Gets There Just the Same and Fifth Street Blues, Davenport played in a slower blues style that was perhaps influenced by Williams and other peers, and belied his rough and tumble boogie woogie style. He also sang very competently and bantered a bit with Dora. Then came the initial recording of the tornado that was Cow Cow Blues. While some have argued that this was the first recording of boogie woogie, it was actually predated nearly two years by George Thomas with his rendition of The Rocks on Gennett. However, it is the earliest track cast in his unique grinding boogie style. Dora sang a fine blues and provided some exclamations over Cow Cow's persistent riffs.

There is some question of the authorship of the piece, since the main left-hand riff at the beginning of each strain sounds nearly identical to the trio of Trilby Rag, which was written by composer Carey Morgan in 1915. There is little doubt that this popular vaudeville rag was heard by Davenport at some point during his time on stage. It can be, and has been argued, that the strain used by Morgan had been around for a while as well, and Morgan may simply have been the first to notate it. Even if it is a reuse of the theme, Trilby Rag executes the pattern on a major seventh pattern, while Davenport leans more toward an authentic blues-driven minor seventh pattern with some rhythmic variations in both hands. So the correct assessment may be that Cow Cow Blues was influenced by Trilby Rag, but is not fully a copy (a point to which the author, who has regarded the tune as a partial plagiarism for many years, is willing to concede after some careful analysis). That strain would also be copied or reused by other boogie woogie and blues players for several decades to come, and was further reused by Davenport now and then.

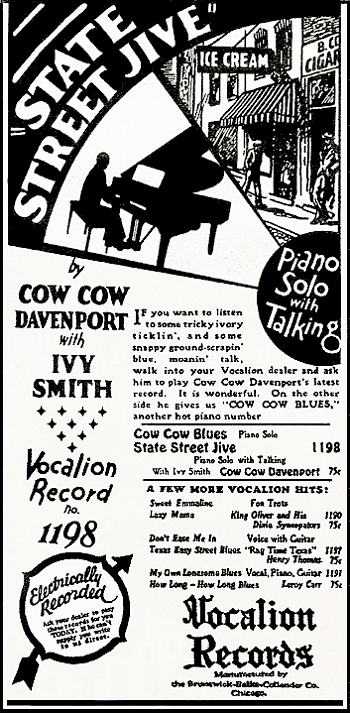

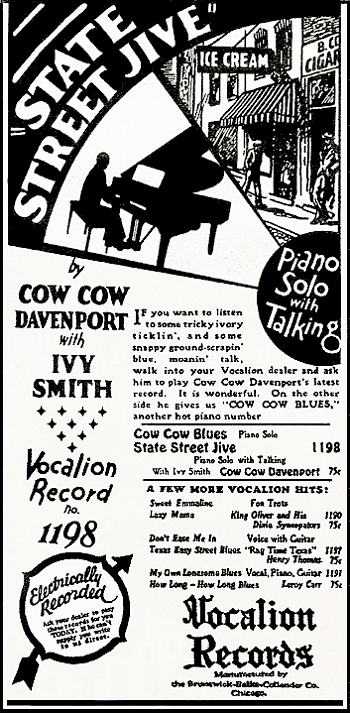

Charles and Dora had one more session at OKeh in early 1926. Then, at some point during the year, she lost interest in her accompanist and found another man, leaving Charles a solo act. He still managed to find work around Chicago, and may very well have exercised some indirect influence on some future boogie players a bit younger than himself, Chicago residents Meade "Lux" Lewis and Albert Ammons, and recent transplant from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Clarence "Pine Top" Smith. He also made friends with Jimmy Yancey, who was a bit closer to him in age. Other than the Thomas brothers, most of the core of boogie woogie players were present and performing in Chicago and nearby towns in the 1927-1929 time period. For Cow Cow, this included recording dates for Paramount Records accompanying a few instrumentalists with a small ensemble in early 1927. These sessions yielded not only his experiential and telling Jim Crow Blues, but some of Davenport's first tracks cut with the largely unknown blues singer Ivy Smith.

He still managed to find work around Chicago, and may very well have exercised some indirect influence on some future boogie players a bit younger than himself, Chicago residents Meade "Lux" Lewis and Albert Ammons, and recent transplant from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Clarence "Pine Top" Smith. He also made friends with Jimmy Yancey, who was a bit closer to him in age. Other than the Thomas brothers, most of the core of boogie woogie players were present and performing in Chicago and nearby towns in the 1927-1929 time period. For Cow Cow, this included recording dates for Paramount Records accompanying a few instrumentalists with a small ensemble in early 1927. These sessions yielded not only his experiential and telling Jim Crow Blues, but some of Davenport's first tracks cut with the largely unknown blues singer Ivy Smith.

He still managed to find work around Chicago, and may very well have exercised some indirect influence on some future boogie players a bit younger than himself, Chicago residents Meade "Lux" Lewis and Albert Ammons, and recent transplant from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Clarence "Pine Top" Smith. He also made friends with Jimmy Yancey, who was a bit closer to him in age. Other than the Thomas brothers, most of the core of boogie woogie players were present and performing in Chicago and nearby towns in the 1927-1929 time period. For Cow Cow, this included recording dates for Paramount Records accompanying a few instrumentalists with a small ensemble in early 1927. These sessions yielded not only his experiential and telling Jim Crow Blues, but some of Davenport's first tracks cut with the largely unknown blues singer Ivy Smith.

He still managed to find work around Chicago, and may very well have exercised some indirect influence on some future boogie players a bit younger than himself, Chicago residents Meade "Lux" Lewis and Albert Ammons, and recent transplant from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Clarence "Pine Top" Smith. He also made friends with Jimmy Yancey, who was a bit closer to him in age. Other than the Thomas brothers, most of the core of boogie woogie players were present and performing in Chicago and nearby towns in the 1927-1929 time period. For Cow Cow, this included recording dates for Paramount Records accompanying a few instrumentalists with a small ensemble in early 1927. These sessions yielded not only his experiential and telling Jim Crow Blues, but some of Davenport's first tracks cut with the largely unknown blues singer Ivy Smith.A number of historians and researchers have tried to pin down some kind of identification on Ivy Smith (seen on one set of recordings as Iva Smith, but with no definitive results. Smith may have been a stage name, and it is possible that she was really Iva France It is unclear if she was paired with Charles for the recording sessions, or if he found her while performing somewhere. Their first session was at Paramount in January of 1927, followed by another one in April, which collectively yielded seven sides, along with a few more which had Charles accompanying cornetist B.T. Wingfield and violinist Leroy Pickett. Ivy turned out to be a capable blues singer, but was not found on the regular circuits with the others like Bessie Smith or Ma Rainey. Her performances were a bit more subtle but, to some, persuasive in many regards, particularly to Davenport's laid back accompaniments.

Davenport was relatively busy in the recording study over the next two years, largely for Vocalion in 1928 and Gennett in 1929 in Richmond, Indiana. In 1928 he recorded a few tracks with Ivy, who was uncredited on some, offering more vocal commentary than anything else. There were a number of sides with accompaniment for singer "Hound Head" Henry (whose real identity remains obscured), some written with Billy Dunn and finding their way into published form. Some of Henry's vocals could be termed novelty blues, as he tended to make a lot of noise, laughing, crying, imitating train and boat whistles, and even bird calls. A few more sides were done with Jim Towel and Memphis Joe. Throughout these, Davenport's accompaniment was steady and consistent.

There were a number of sides with accompaniment for singer "Hound Head" Henry (whose real identity remains obscured), some written with Billy Dunn and finding their way into published form. Some of Henry's vocals could be termed novelty blues, as he tended to make a lot of noise, laughing, crying, imitating train and boat whistles, and even bird calls. A few more sides were done with Jim Towel and Memphis Joe. Throughout these, Davenport's accompaniment was steady and consistent.

There were a number of sides with accompaniment for singer "Hound Head" Henry (whose real identity remains obscured), some written with Billy Dunn and finding their way into published form. Some of Henry's vocals could be termed novelty blues, as he tended to make a lot of noise, laughing, crying, imitating train and boat whistles, and even bird calls. A few more sides were done with Jim Towel and Memphis Joe. Throughout these, Davenport's accompaniment was steady and consistent.

There were a number of sides with accompaniment for singer "Hound Head" Henry (whose real identity remains obscured), some written with Billy Dunn and finding their way into published form. Some of Henry's vocals could be termed novelty blues, as he tended to make a lot of noise, laughing, crying, imitating train and boat whistles, and even bird calls. A few more sides were done with Jim Towel and Memphis Joe. Throughout these, Davenport's accompaniment was steady and consistent.Cow Cow really launched into his most productive period in 1929 at both Vocalion and Gennett, recording not only with Ivy again (listed on some tracks as Ruby Rankin), but the Southern Blues Singers (who he probably joined on vocals) and guitarist and vocalist "Lovin'" Sam Theard. Despite this, it is some of solos which stand out, particularly his Atlanta Rag. Unlike Cow Cow Blues, this is almost a direct lift from the aforementioned Trilby Rag by Carey Morgan, excising the B section and launching into the trio in the same key. A couple of original sections or variations follow this. It remains a vivacious performance of ragtime that is likely not too far off from what was heard in the mid-to-late 1910s, and could also support that he had actually worked in Atlanta at some point, thus the reference in the title. Was it an original? This would be a matter of perspective and analysis for musicologists to sort out. However, it was a popular record just the same. Overall, he cut around 34 issued sides that year, with several more takes unissued, which was a pretty good volume for a black piano player at that time, particularly one not engaged in some of the more mainstream popular music trends. It was reported that he was also a staff arranger, composer and talent scout for black producer Mayo Williams, the head of the Vocalion label, which was the Brunswick Records race record subsidiary. During this time, he made a steady $85 per week, and was able to afford a relatively nice apartment at 35th and Wabash. He also later recalled that he believed Paramount, where Williams had previously worked, owed him some $3,000 in royalties from sales of his 1927 sessions.

Around this same period, Meade "Lux" Lewis had already recorded his iconic Honky Tonk Train Blues, although its release was delayed for well over a year, and Clarence "Pine Top" Smith had cut his entirety of sides for Vocalion between December of 1928 and his untimely death in early 1929, sessions that Cow Cow perhaps rightfully claims to have facilitated. He had not only said he found Smith playing in Pittsburgh in late 1927 or early 1928. According to Davenport by way of performer/promoter Art Hodes in the Jazz Journal of May 1959:

I happened to hit Pittsburgh at the Star Theater on [Wylie] Avenue. Being a piano player I would go around to all the honky-tonks in town. I went with a friend of mine to the Sachem Alley, and there I met Pine Top Smith. He had heard my "Cow Cow Blues," wanted to meet me. He sat down playin'. Didn' know what he was playin', so I said, 'Boy, look here, you sure have got a mean boogie woogie.' Pine Top didn't know what he was playin' nohow. I began to tell him what it was, then he tried to sing it. He never could rhyme it together, just said 'Come up here gal, to this piano… playin' my boogie woogie'.

In essence, Davenport claims to have given Pine Top the name of his most identifiable piece that also helped to define the genre, which may be a bit of a stretch, but the story is included here for context. Note that according to historian and performer Bob Pinsker, Wylie Avenue (misspelled as Wile in the article) was in the center of the black community of Pittsburgh during that era. According to Cow Cow he encouraged Smith to move his family to Chicago. There he roomed in the same building as Ammons and Lewis, and all of them played on the same party circuits as Davenport. It was through the popular recording of Pine Top's Boogie Woogie that word of both the type and the name of the music spread outward from Chicago, and Charles was somehow involved with it. However, he failed to get either Ammons or Lewis into Vocalion that year, and by 1930 it was pretty much too late to do so.

Note that according to historian and performer Bob Pinsker, Wylie Avenue (misspelled as Wile in the article) was in the center of the black community of Pittsburgh during that era. According to Cow Cow he encouraged Smith to move his family to Chicago. There he roomed in the same building as Ammons and Lewis, and all of them played on the same party circuits as Davenport. It was through the popular recording of Pine Top's Boogie Woogie that word of both the type and the name of the music spread outward from Chicago, and Charles was somehow involved with it. However, he failed to get either Ammons or Lewis into Vocalion that year, and by 1930 it was pretty much too late to do so.

Note that according to historian and performer Bob Pinsker, Wylie Avenue (misspelled as Wile in the article) was in the center of the black community of Pittsburgh during that era. According to Cow Cow he encouraged Smith to move his family to Chicago. There he roomed in the same building as Ammons and Lewis, and all of them played on the same party circuits as Davenport. It was through the popular recording of Pine Top's Boogie Woogie that word of both the type and the name of the music spread outward from Chicago, and Charles was somehow involved with it. However, he failed to get either Ammons or Lewis into Vocalion that year, and by 1930 it was pretty much too late to do so.

Note that according to historian and performer Bob Pinsker, Wylie Avenue (misspelled as Wile in the article) was in the center of the black community of Pittsburgh during that era. According to Cow Cow he encouraged Smith to move his family to Chicago. There he roomed in the same building as Ammons and Lewis, and all of them played on the same party circuits as Davenport. It was through the popular recording of Pine Top's Boogie Woogie that word of both the type and the name of the music spread outward from Chicago, and Charles was somehow involved with it. However, he failed to get either Ammons or Lewis into Vocalion that year, and by 1930 it was pretty much too late to do so.Once the Great Depression hit, the music industry was one of the earliest entities that suffered, with the exception of those involved in radio. Consumers suddenly had no taste to spend their shrinking dollars on records, much less needles or new phonographs, and instead invested in radio receivers. In fact, to track this trend, the 1930 Federal census had a column asking if there was a radio set in the enumerated households. Cow Cow and Ivy managed one final hurrah down in Richmond at Gennett in June, but there would be no apparent recording opportunities after that. At least two sources indicate that Charles was married to an Iva France, and given that the act continued for a while and that for one session Ivy was billed as Iva, this helps to solidify the probability that they were one and the same. Charles and Ivy were performing in Chicago and on various vaudeville circuits as The Chicago Steppers from 1928 to 1930. Around that time, he obtained a bus, charging it against his expected Paramount royalties, and hired a small troupe of performers to help enhance his road show. They saw some success in Kansas City, Missouri, but started to experience resistance once they reached Dallas, Texas. Live shows were now considered luxuries. At their final stop in Mobile, Alabama, the troupe disbanded. Davenport had no recourse other than pawning his bus to pay his troupe. He would earn a little and get it back on a few occasions, only to pawn it again. Authorities caught on to this, and Davenport ended up in jail (possibly for fraud). According to a later recollection as relayed by Art Hodes:

They caught me and gave me six months in Camp Kilby, out from Montgomery. It gave me a chance to think. All my show folks left, bus gone and me in prison. I couldn't do any farm work, in fact, I couldn't do anything. I had never worked before. After I got my whippings they decided I couldn't work. They put me with the old men as a gardener. Naturally, I sat down on the ground. I caught pneumonia. It must have settled in my right arm.

Now broke and experiencing some arthritis and mild paralysis in his right arm, Charles decided to not return to hard-hit Chicago, as did many other musicians of the period. He worked briefly in Florida for Haeg's Circus on stage as a minstrel, but ended up opting out of this life as it took a toll on his body. Cow Cow eventually relocated his home base to Cleveland, Ohio, which is where his sister Martha had settled, and where he would continue to return for the rest of his life. In the interim, he rejoined the dying TOBA circuit trying to adapt to the new reality of the economic downturn and changing trends in music. At some point between 1936 and 1937 he met Peggy Taylor (possibly born as Carrie Williams), a singer and dancer who utilized snakes in her act. For whatever reason, Cow Cow found her hard to resist, and endeavored to join forces with her, even in his diminished capacity. They teamed up with Charles fronting her show. "I got a cowboy hat and went on the front to talk." Given the type of show it was, it is no surprise that they ended up having issues with law enforcement for various infractions, some of them undoubtedly dealing with snakes and unpaid debts.

In the interim, he rejoined the dying TOBA circuit trying to adapt to the new reality of the economic downturn and changing trends in music. At some point between 1936 and 1937 he met Peggy Taylor (possibly born as Carrie Williams), a singer and dancer who utilized snakes in her act. For whatever reason, Cow Cow found her hard to resist, and endeavored to join forces with her, even in his diminished capacity. They teamed up with Charles fronting her show. "I got a cowboy hat and went on the front to talk." Given the type of show it was, it is no surprise that they ended up having issues with law enforcement for various infractions, some of them undoubtedly dealing with snakes and unpaid debts.

In the interim, he rejoined the dying TOBA circuit trying to adapt to the new reality of the economic downturn and changing trends in music. At some point between 1936 and 1937 he met Peggy Taylor (possibly born as Carrie Williams), a singer and dancer who utilized snakes in her act. For whatever reason, Cow Cow found her hard to resist, and endeavored to join forces with her, even in his diminished capacity. They teamed up with Charles fronting her show. "I got a cowboy hat and went on the front to talk." Given the type of show it was, it is no surprise that they ended up having issues with law enforcement for various infractions, some of them undoubtedly dealing with snakes and unpaid debts.

In the interim, he rejoined the dying TOBA circuit trying to adapt to the new reality of the economic downturn and changing trends in music. At some point between 1936 and 1937 he met Peggy Taylor (possibly born as Carrie Williams), a singer and dancer who utilized snakes in her act. For whatever reason, Cow Cow found her hard to resist, and endeavored to join forces with her, even in his diminished capacity. They teamed up with Charles fronting her show. "I got a cowboy hat and went on the front to talk." Given the type of show it was, it is no surprise that they ended up having issues with law enforcement for various infractions, some of them undoubtedly dealing with snakes and unpaid debts.The couple would move in together and get married in Cleveland around 1937, at least they might have as a legal record is hard to find. Then Peggy went to work for the city. Charles also took advantage of some of the Federal programs getting people back to work, and took a job with the WPA, becoming a supervisor for some Cleveland recreational programs. He had all but given up on show business, yet kept in contact with Mayo Williams, who was now working for Decca Records following their acquisition of Vocalion. Mayo finally responded to Davenport in mid-1938 to set up a recording session. However, it was not quite in time. Davenport had suffered a severe stroke early in the year which debilitated his playing ability, adding to the physical woes he was already experiencing. The May 8, 1938 New York City session resulted in just five usable sides. Cow Cow could not play, so was reduced to providing vocals for the pieces, while accompanied by Decca house musicians who were also engaged that day to record with vocalist Jimmie Gordon. Sammy Price, who had worked with Cow Cow previously in some capacity, was at the piano. This was likely a frustration since Davenport perhaps hoped for a comeback of some kind, yet his body defied him in that effort. To add to that frustration, at the end of the year some of his Chicago disciples, mainly Lewis and Ammons joined by Pete Johnson, would stage a musical coup that put boogie woogie front and center before the American public, albeit only for about four years.

This was likely a frustration since Davenport perhaps hoped for a comeback of some kind, yet his body defied him in that effort. To add to that frustration, at the end of the year some of his Chicago disciples, mainly Lewis and Ammons joined by Pete Johnson, would stage a musical coup that put boogie woogie front and center before the American public, albeit only for about four years.

This was likely a frustration since Davenport perhaps hoped for a comeback of some kind, yet his body defied him in that effort. To add to that frustration, at the end of the year some of his Chicago disciples, mainly Lewis and Ammons joined by Pete Johnson, would stage a musical coup that put boogie woogie front and center before the American public, albeit only for about four years.

This was likely a frustration since Davenport perhaps hoped for a comeback of some kind, yet his body defied him in that effort. To add to that frustration, at the end of the year some of his Chicago disciples, mainly Lewis and Ammons joined by Pete Johnson, would stage a musical coup that put boogie woogie front and center before the American public, albeit only for about four years.The 1940 census showed Cow Cow and Peggy, lodging in the home of Clarence Fuller in Cleveland. She was listed as a laborer of some kind and he was shown to be a supervisor for a recreational bath house. For the 1942 draft, Davenport was shown working for a WPA Training School in nearby Collinwood. He suffered another stroke in 1942 that further deteriorated his pianistic abilities, which had been on the mend. Then there was the release of Cow Cow Boogie which hit the stores and the airwaves in 1942. It was one of the first discs to emerge from fledging Capitol Records which had just been started by Johnny Mercer, and helped to put them on the map. With a vocal by seventeen-year-old Ella Mae Morse accompanied by Freddie Slack and his orchestra, it was essentially a cowboy song with a mild boogie woogie left hand, but it was not boogie woogie, nor was it Davenport's. Whether composers Don Raye and Gene DePaul, who had written the tune for the Abbott and Costello Film Ride 'Em Cowboy, actually knew who Charles was, or were perhaps just playing on the title they had heard in the past is unclear.

Just the same, the tune has been recorded several times since the original 1942 track, and very often improperly associated with the real Cow Cow Davenport, who could only wish he had the income derived from the song. (Reports that he had actually written the song and then subsequently signed the rights away for $500 are difficult to substantiate, and given the style, unlikely. He does appear to have possibly sued for use of the title, receiving a $500 out of court settlement.)

|

Despite the confusion, there was some developing residual interest in the original Cow Cow Blues and associated recordings, which led to some new interest in him, and a turn of fortune to a degree. Price, who had accompanied Davenport at the Decca sessions, recorded his own version of Cow Cow Blues in 1940, followed by pianist Bob Zurke's orchestra a few months later. In an article from that period it was stated that he found "the going a little tough these days, but hoped he has not been forgotten in the realm of hot music." His rediscovery was also helped a bit by jazz/boogie woogie pianist and journalist Art Hodes, who had been playing and discussing jazz recordings and artists on the radio since around 1938 as well as writing articles for Jazz Information, and later Jazz Record magazines (the latter associated with a similarly named record label). He was introduced to Cow Cow by Herb Abramson during a visit to New York in which Cow Cow was trying to sell some of his compositions to publishers. Hodes asked him to do his afternoon show on June 3, 1942, on WNYC. It was advertised as an interview with the "father of modern boogie-woogie. In the interim, Charles found temporary work as an attendant in the men's room at the Onyx Club. While he was not playing particularly well, his singing and stories got him through the interview and impressed Hodes as well. This resulted in publicity, then record sales, then further interest by Hodes who felt that this pioneer had been wrongfully neglected to some extent by the public, and even by some of his peers.

The vogue for boogie woogie had all but passed as World War II gained momentum, although some of it found its way into the popular swing music of the period. Charles oscillated between Cleveland and New York through the next several years, and slowly regained his strength enough to play relatively competently once again. He would take day jobs washing dishes or as a men's room attendant, while working small clubs at night. With the assistance of Hodes Cow Cow recorded at least four more sessions. One of them was for J. H. Alderton, Junior's small Comet label in 1945, resulting in eight released sides. He also cut sides for Solo Art and the Jazz Record label, none of which were released. An additional session with Circle Records facilitated by author and historian Rudi Blesh included interviews with Charles and Peggy. Hodes utilized him as an editor for Jazz Record Magazine for a while. Cow Cow was part of a Blue Note concert held at Town Hall in New York in 1945. Back in Cleveland he got a semi-regular gig at the Starlite Grill. However, one of his proudest achievements was facilitated in part by Hodes and his circle of friends.

An additional session with Circle Records facilitated by author and historian Rudi Blesh included interviews with Charles and Peggy. Hodes utilized him as an editor for Jazz Record Magazine for a while. Cow Cow was part of a Blue Note concert held at Town Hall in New York in 1945. Back in Cleveland he got a semi-regular gig at the Starlite Grill. However, one of his proudest achievements was facilitated in part by Hodes and his circle of friends.

An additional session with Circle Records facilitated by author and historian Rudi Blesh included interviews with Charles and Peggy. Hodes utilized him as an editor for Jazz Record Magazine for a while. Cow Cow was part of a Blue Note concert held at Town Hall in New York in 1945. Back in Cleveland he got a semi-regular gig at the Starlite Grill. However, one of his proudest achievements was facilitated in part by Hodes and his circle of friends.

An additional session with Circle Records facilitated by author and historian Rudi Blesh included interviews with Charles and Peggy. Hodes utilized him as an editor for Jazz Record Magazine for a while. Cow Cow was part of a Blue Note concert held at Town Hall in New York in 1945. Back in Cleveland he got a semi-regular gig at the Starlite Grill. However, one of his proudest achievements was facilitated in part by Hodes and his circle of friends.As early as the mid-1930s, Cow Cow had applied for entry into ASCAP, based both on publications of his works and his volume of original tunes on record. Despite claims that racism was at a minimum in that organization, there were still some biases against certain classes of artists and composers, and boogie woogie appears to have had a stigma attached to it. Once it became more popular in the early 1940s through white artists, as well as promoters like Hodes and John Hammond of Columbia Records, the odds increased in Charles' favor. Finally, through the efforts of Hodes and his friend, Columbia record producer George Avakian, Charles Davenport became a certified member of ASCAP in 1946, and was then entitled to receive royalties for recordings and sheet music sales of his work. While this was a minimal amount at best, it still was considered a victory of sorts by all involved.

After an appearance at the Stuyvesant Casino in New York in 1948, Charles finally all but gave up on making a living in music and spent the remainder of his years in Cleveland with Peggy. He found work at Thomson Products, a postwar defense plant, where he stayed as long as he was able. As the honky tonk and boogie woogie revivals of the late 1940s took hold there was more interest in the pioneer player once again, and he was included in at least one lecture event at Cleveland College in late 1949. Clarence Williams also published a couple of folios that included transcriptions of Cow Cow Blues and various other works.

The 1950 census, taken in Cleveland, raises a question as to his actual overall status. It showed Charles as without an occupation, Peggy, under her last name of Taylor, working as a crafts instructor at a local recreation center, and both of them as widowed rather than married, which again raises the question of whether they had done so legally. It might be an enumerator error, or, if intentional, deflective for some unknown reason. Peggy is further shown as a roomer in Davenport's home.

|

Even in his early sixties, Charles still persisted in being relevant. In a July 3, 1955 article in a Cleveland newspaper, he made it clear that he was not ready to retire, and even had three songs prepared for publication at that juncture.

Those old boogie-woogie blues will soon be rolling out again for a famous old-time who refuses to give up—Cow Cow Davenport. Twelve years ago he picked up a cup of coffee and was startled to fine he couldn't hold it. That was the start of a stroke that cost him his piano-playing career. But not his life-long love for music…

A week from tomorrow he will have another musical "opening," his own record shop at 7706 Kinsman Avenue S.E. … Cow Cow's top time, himself, was in Chicago in the 30's… Altogether he wrote 133 songs and has 89 on the market.

Who's his favorite? The late great Thomas Wright (Fats) Waller.

Cow Cow's wife, the former Carrie Williams [as per the earlier reference, this was likely Peggy], wrote "I can't Sleep" for Montana Taylor in 1944 and has three other songs completed. She is considered to be the first woman to introduce jazz into the midwest [sic]. Today she is a craft instructor at the Kinsman Home Center and active in the Gilpin Players of Karamu House.

However, his new career was not to last for very long. Continued hardening of the arteries finally took the self-proclaimed originator of boogie woogie just a few months later in December of 1955 in Cleveland, and he was interred in Evergreen Cemetery in nearby Bedford Heights. Davenport's work lives on through contemporary performances of his original works, echoes of his style, such as Mess Around by Ray Charles (also covered by Elvis Presley in Viva Las Vegas), which is a reworking of the Cow Cow Blues and its original source, Trilby Rag. There are also collections of his recordings in digital format, available on CDs, downloads and YouTube. Whether or not he actually originated boogie woogie, he was certainly one of the primary parents of the genre and should be perpetually remembered as such.

A number of disparate sources were called on for this challenging essay, most of them with fragmented and sometimes conflicting information on Davenport. An amalgamation of these, and mostly of short essays and articles written about him during his lifetime were averaged out along with the usual demographic sources to construct a relatively accurate narrative, but time lines are still uncertain, given the conflicting stories. Logs and lists of known recordings also helped a bit with locating Charles during each period, as did newspapers and scant directory listings. Special thanks go to boogie woogie performer and historian Carl "Sonny" Leyland for providing some of the newspaper articles referenced for this essay.

Known Copyrighted/Published Compositions

Known Copyrighted/Published Compositions