|

Clifford Frank "Cliff" Hess (June 19, 1891 to June 8, 1959) | |

Known Compositions Known Compositions | |

|

1905

It's a Bird!1914

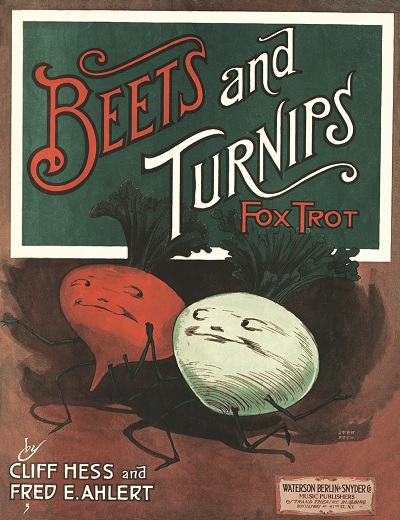

Beets and Turnips: Fox Trot [1]Happiness: A Hesitation Waltz 1915

Bric-A-Brac: Novelty Fox TrotDoodle Bug: Characteristic Rag Ke Aloha (My Love): Hawaiian Waltz Just to Hear Your Voice Again (If Only to Say Goodbye) Popular Rag [2] 1916

Homesickness Blues: Fox TrotThis End Up: One Step Spanish Onion: Eccentric Tango When You Drop Off at Cairo, Illinois [2] 1917

The Ghost WalkRegretful Blues [3] Huckleberry Finn [4,5] Everybody Took a Kick at Nicholas [4,5] While the Years Roll By [4,5] 1918

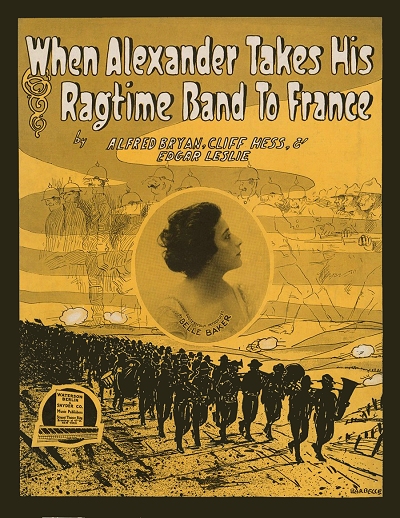

Don't You Remember the Day?Dew Drops Thou Shalt Not Steal Thy Neighbor's Mule When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band to France [6,7] Mary and John [6,7] Mister Moon, How is Everything on No-Man's Land? [8] 1919

On the Trail to Santa Fé(Blue-Eyed, Blond-Haired) Heart-Breaking Baby Doll [8] Sweetie Mine [8] The Wedding of Shimmie and Jazz [9] Freckles [9,10] I Used to Call Her Baby [9,11] What's the Good of Just a Song at Twilight [9,11] Taxation Blues [12,13] East of Suez [12,13] Persian Moon [14] Seven Miles to Arden [15] 1920

The Wedding Bell Blues [9]The Music Salesmen [9] Tom-Boy Girl [9] Marimba [9,16] Pining for Home [9,17] At the Home Brewer's Ball [9,18] 1921

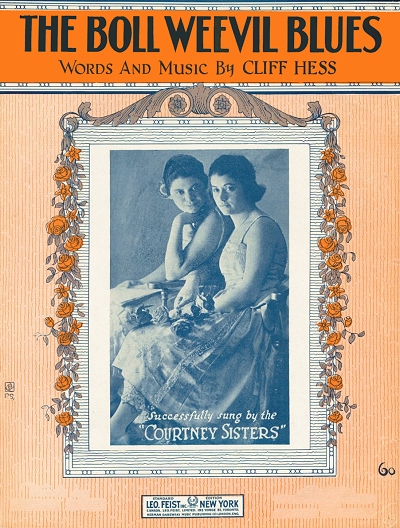

The Boll Weevil BluesOn Honeymoon Isle Brown Eyes, That Give Me the Blues [9] Everybody Called Her Tom Boy Girl [9,10] 1922

While the Years Roll By [4,5,19]Save the Last Waltz for Me [9,19] 1923

Corn on the CobSomehow I'm Always to Blame [20] Bring it With You When You Come [21,22] Shamrock: Musical [13] I Want a Girl Like Mother Was when Mother Was a Girl; Irish Moon; The Two Best Girls I Love 1924

Turn On Your Radio (You Can Listen In onYour Home Town) Blue Ridge Blues [20] I'm a Dreamer Dreaming Love Dreams 1925

FascinationWherever You Go [13] Homeward Bound [13] Wonder Why I Love You Like I Do [25] Hokey Pokey Diddle De Rum [26] 1926

When You Dunk a Doughnut Don' It MakeIt Nice? Baby Face 1927

Swanee Shore [27]1929

Isabella [4,5]Oh My Stock is Going Up with Susie [4,5] Let's Build a Nest for Two [28] I Always Knew it Would Be You [29] 1930

The Hobby Horse ParadeThe Fool's Parade [5] It's a Long, Long Road I'm Travelin' On (But I Got Good Shoes) [5] Ev'rything is Even, Even, Worse Than it Was Before [5,30] 1931

Hello, Better TimesFootlights: Musical Film Saxophone Her; The Secret of a Beautiful Girl; When Love Comes Your Way; The Mill Song; Burning Soles; It Takes the Song of a Bluebird to Chase the Blues Away The Love Department: Musical Film There's an Old Fashioned Cottage 1932

All on Account of YouThe Fireman's Parade Get in the Swim Gossip Song Rodeo Santa Fe Trail Sittin' and Thinkin' of You Sea Legs: Musical Short Same Old Boat; Shake-Shake; Swingin' the Mop 1933

The Double Crossing of Columbus: ShortThe Rhumba Rumble Speaking of Operations: Short Under the Cotton Moon; Lonesome Levee; A Sure Cure for the Blues Pickin' the Winner: Short Pickin' the Winners; The Sweetest Gal in Town The Operator's Opera: Short Walkin' in the Wind with You Use Your Imagination: Short Wouldn't it be Nice The No Man: Short Love Behind a Fan |

1933 (Cont)

Pleasure Island: ShortI'm a Little Co-coa-nut (Shakin' on a Co-coa-nut Tree) Sky Symphony: Musical Short I'm Happy When it Rains; The Spell of the Moon; Men of Steel Twenty Thousand Cheers for a Chain Gang The Sing Sing Serenade Seasoned Greetings: Short Sunny Weather The Mild West: Short Pony Boy; I'll Take 'Em Every Time; Way Down in Texas; Broadway Bubble; Moonlight Memories; A Little Too Late Kissing Time: Short The Bell of San Marco; Drinking Song; All My Life I've Waited for Someone Like You; Love, What Have You Done to Me? Plane Crazy: Short I Feel I'm Safe with You; Make You Feel at Home; Pretty Face; As Long as the Ganges Flows Picture Palace: Short Occupation Song; If It's Love; Born That Way 1934

Private Lessons: ShortSnow Song; Follow Me; Let's Dance; Red Headed and Blue; Yoo Hoo Hoo Manhattan Clock Tale: Short Love and Learn Mardi Gras: Short The Rhythm of the Paddle Wheel; Alone Darling Enemy: Short Pretense; Sweetheart of the Regiment; Forgive and Forget; The Girl Behind the Moon; Tonight's the Night; Frieda Who is That Girl?: Short Is This Love?; Hail Ducania; That Melody from Out of the Past; Who is That Girl?; Brotherhood Song The Winnah: Short School Days; Springfield Song; On Your Toes; It's Just That Kind of a Day; Alma Mater Service with a Smile: Short Service with a Smile; Golf Number; What's You Gonna Do Now? Good Morning Eve: Short Rhythm in the Bow; In Good Old King Arthur's Reign; Lookin' 'Em Over; Down the Road of Time 1935

In This Corner: ShortWhat Are You Doing to Me?; Down in Sunny Minstrel Land; You Gotta Be Seen; My Dream Boat is a Mississippi Show Boat; Minstrel Men of Yesterday The Film Follies: Short Broken Hearts of Hollywood; On the Downtown Express The Lady in Black: Short Show Song; The Lady in the Black Dress Hear Ye! Hear Ye!: Short Adieu to Love Surprise: Short Dixie is Calling; Goodbye, Alma Mater; I'm Don Bolero Vasquero Bolero; If the Volga Flowed Through Dixie Dublin in Brass: Short [31] That's How I Spell "Ireland"; Any Place is Heaven with an Angel Like You; Stop!; You'll Always Have the Right of Way 1936

Rhythmitis: Musical ShortTangle Feet 1937

Captain Blue Blood: Musical FilmNew Orleans; What Do I Have to Do to Be Loved; The King of France Commands Toot Sweet: Musical Film Don't Forget to Ask for Fifi 1938

If I Hadn't Met You [4,32]I Love to Ride on a Choo-Choo Train [32] Never Felt Better, Never Had Less [32] 1942

If I Do, I Ded a Whippin', I Dood It [32,33]1943

The Great Day of Victory!Hostess in the U.S.O. [32] 1952

I'm Gonna Be Busy Dating You, Darling, Monday thru Sunday [32]1953

You Rang the Bell With Me (Ting-a-ling, Ting-a-ling, Ting-a-ling) [32]

1. w/Fred E. Ahlert

2. w/E. Ray Goetz 3. w/Grant Clarke 4. w/Sam M. Lewis 5. w/Joe Young 6. w/Alfred Bryan 7. w/Edgar Leslie 8. w/Sidney D. Mitchell 9. w/Howard E. Johnson 10. w/Milton Ager 11. w/Murray Roth 12. w/Joe Rosey 13. w/Joseph H. Santly 14. w/Mel B. Kaufman 15. w/Oliver Morosco 16. w/Johnny Black 17. w/Ethel Bridges 18. w/Theodore Morse 19. w/Cliff Hess as Jack Austin 20. w/Cliff Hess as Roy B. Carson 21. w/Cliff Hess as Earl Bray 22. w/Charles Landa & Lew Coby 23. w/Porter Grainger 24. w/Percy Grainger 25. w/Daniel Yates 26. w/Wendell Woods Hall 27. w/Charles A. Bourne 28. w/Frank L. Ventre 29. w/Jacob Coopersmith 30. w/Al White 31. w/Sanford Green 32. w/Abel Baer 33. w/Joe Rines |

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |

|

1919

Freckles [1]Regretful Blues [2] 1920

I'd Like to Find the Fellow that WroteDardanella [3] 1921

Roll On Silvery Moon [4]Remember the Rose [4] 1923

Slipova [4]Corn on the Cob [4] Upright and Grand [5] Corn on the Cob [4,6] Shake Your Feet [4] Covered Wagon Days [4] 1924

All Alone [7]Dreamer of Dreams [7] 1926

For My Sweetheart [8]We Will Meet at the End of the Trail [8]

1. w/Blossom Seeley

2. w/Benny Fields 3. w/Bob Miller 4. Piano duet w/Frank E. Banta |

Matrix and Date

[Victor Trial 12-18-02] 12/18/1919[Victor Trial 12-18-04] 12/18/1919 [Columbia 80104] 12/??/1921 [OKeh 71303] 02/??/1923 [Vocalion 11855] 08/??/1923 [Vocalion 11933] 09/??/1923 [Vocalion 12240] 11/??/1923 [Vocalion 12243/4] 11/??/1923 [Vocalion 139??] 11/??/1924 [Columbia 142830] 10/18/1926

5. w/The Ambassadors

6. w/The Broadway Sycnopators 7. w/Marie Dawson Morrell, violin 8. w/Confidential Charley |

Selected Rollography Selected Rollography | |

|

Ja-Da

The Wedding of Shimmie and Jazz Taxation Blues Show Me How Palesteena La Veeda Pretty Little Cinderella Rose of Washington Square Anytime, Anyday, Anywhere Just Like a Gypsy Wondering I Love You Sunday The West Texas Blues In an Old Fashioned Cottage You're Just Like the Rose Hula Blues Marimba Bright Eyes I Wonder Why I Call You Sunshine Stolen Kisses My Sunny Tennessee [1] Lonesome and Blue Say it With Music [1,2,3,4,5] Wabash Blues [1] Plantation Lullaby [1] The Sneak [1] Don't Think You'll Be Missed [2] Jealous [6] The Love Nest Corn on the Cob Humming Snow Flake East of Suez Somebody Georgia I'll Say She Does I Want to Be Happy [5] My Heart Stood Still When My Shoes Wear Out from Walking

1. w/Frank E. Banta

2. w/Rudolph O. Erlebach 3. w/Phil Ohman |

[Vocalstyle 11302]

[Vocalstyle 11467] [Vocalstyle 11480] [MelODee 2946] [MelODee 2955] [MelODee 3847] [MelODee 3849] [MelODee 3851] [MelODee 3909] [MelODee 3921] [MelODee 4009] [MelODee 4017] [MelODee 4051] [MelODee 4059] [MelODee 4105] [MelODee 4113] [MelODee 4185] [MelODee 4207] [MelODee 4245] [MelODee 4353] [MelODee 4473] [MelODee 4513] [MelODee 4553] [MelODee 4561] [MelODee 4595] [MelODee 4629] [MelODee 4789] [MelODee 5006] [MelODee 5272] [MelODee 203587] [MelODee 204133] [MelODee ????] [MelODee ????] [Duo-Art 1633] [Duo-Art 1661] [Duo-Art 1787] [Duo-Art 10012] [Duo-Art 173015] [Ampico 209511] [Golden Age 1118]

4. w/Henry Lange

5. w/Frank Milne 6. w/Bud Earl |

Many historians are aware of the name of Cliff Hess, and even the average old music lover has seen it now and then, and even heard a bit of his musicality in his limited repertoire of recordings or some of his compositions. But other than the historians, most are not aware that they have been exposed to a lot more of Hess's work than they know, at least in the way it helped to shape some of the early output of another very well-known composer. While he got his start in ragtime, or at least during the ragtime era, Cliff endured well beyond, also creating some of the soundtrack of the Great Depression, much of which was designed to distract people from the reality of the time and help them to escape to a happier place. So now the question might be "Who is this Cliff Hess and why should I know more about him?"

From Riverboats to The King's Secretary

Clifford Hess was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the only child of garment worker Frank C. Hess and his bride Elizabeth Marie Fischer. The 1900 census taken in Cincinnati described Frank as a clothing cutter. Cliff was largely educated in Cincinnati, receiving some private instruction in music, theory and harmony along the way. He was either precocious enough or experienced enough to have his first known instrumental work, It's a Bird, issued by Cincinnati publisher Groene in 1905 when he was still only 14-years-old. From his mid-to-late teens Cliff worked as a pianist on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers on various packets and riverboats. He later told the Music Trade Review that during this time he had "a full chance to study the harmonies of the negro [sic] deck hands." By 1910 Cliff had settled, for a time, in Chicago, Illinois. He was found in the 1910 enumeration living there as a boarder, and working as an actor in the theatre, although more likely a singing pianist.

Cliff was largely educated in Cincinnati, receiving some private instruction in music, theory and harmony along the way. He was either precocious enough or experienced enough to have his first known instrumental work, It's a Bird, issued by Cincinnati publisher Groene in 1905 when he was still only 14-years-old. From his mid-to-late teens Cliff worked as a pianist on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers on various packets and riverboats. He later told the Music Trade Review that during this time he had "a full chance to study the harmonies of the negro [sic] deck hands." By 1910 Cliff had settled, for a time, in Chicago, Illinois. He was found in the 1910 enumeration living there as a boarder, and working as an actor in the theatre, although more likely a singing pianist.

Cliff was largely educated in Cincinnati, receiving some private instruction in music, theory and harmony along the way. He was either precocious enough or experienced enough to have his first known instrumental work, It's a Bird, issued by Cincinnati publisher Groene in 1905 when he was still only 14-years-old. From his mid-to-late teens Cliff worked as a pianist on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers on various packets and riverboats. He later told the Music Trade Review that during this time he had "a full chance to study the harmonies of the negro [sic] deck hands." By 1910 Cliff had settled, for a time, in Chicago, Illinois. He was found in the 1910 enumeration living there as a boarder, and working as an actor in the theatre, although more likely a singing pianist.

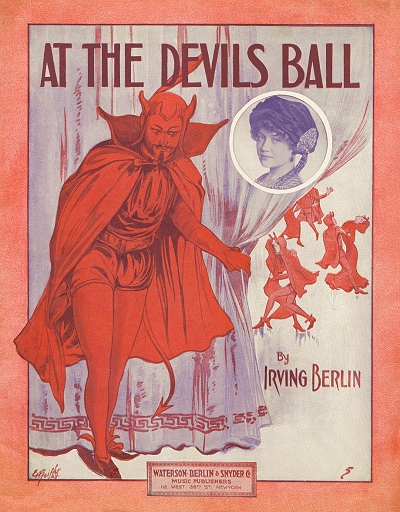

Cliff was largely educated in Cincinnati, receiving some private instruction in music, theory and harmony along the way. He was either precocious enough or experienced enough to have his first known instrumental work, It's a Bird, issued by Cincinnati publisher Groene in 1905 when he was still only 14-years-old. From his mid-to-late teens Cliff worked as a pianist on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers on various packets and riverboats. He later told the Music Trade Review that during this time he had "a full chance to study the harmonies of the negro [sic] deck hands." By 1910 Cliff had settled, for a time, in Chicago, Illinois. He was found in the 1910 enumeration living there as a boarder, and working as an actor in the theatre, although more likely a singing pianist.For the next couple of years, Cliff worked in theaters and with vaudeville shows, sometimes going on the road with one or another singer or troupe. He often worked as an arranger for a show, providing a harmonized piano score at the very least. This put him in good stead with the Chicago branch of the growing New York firm of Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, the latter two being composers Irving Berlin and Ted Snyder. He was working there as a song plugger at the very least, and possibly a copyist or arranger, when good fortune came his way in the form of one of his bosses who he had potentially not previously met since Berlin lived in New York City. While Irving was a talented songwriter, he knew pretty much from lyrics and melody, yet had to be helped with harmonizing and scoring a song, since he could not read or write music, and was limited to performing only in the key of F# major, which was commonly if unkindly referred to as the "nigger key" during that period. [Berlin had five special transposing pianos built for him so he could accompany singers in any key just by sliding the keyboard under the action to the desired key.] As for Hess' role in Berlin's life, it was instantiated by Berlin's handicap, as per a later account in an Edison Records flyer advertising Billy Murray's recording of In My Harem.:

Mr. Berlin has had little practical instruction in music, and, although he plays the piano exceptionally well he plays by ear only. At the time "In My Harem" was written, Mr. Hess was working in the Chicago office of the Waterson, Berlin and Snyder Company. Berlin went to Chicago on the 20th Century Limited and worked out this tune in his head while on the train. When in Chicago he played it over (all on the black keys, as he always does) and Mr. Hess sat by him and wrote it down on paper as he played it. This struck the composer as a great time-saving device, for Mr. Hess afterwards transposed it into a simpler key, and arranged it in its less complicated commercial form.

Almost immediately, in early 1913, Hess found himself in Manhattan, having been hired by Berlin as a full-time "private secretary," which really was more like his right hand assistant in regards to Berlin's composing. Up to this point, Irving had engaged other composers or arrangers at associated with Snyder at need in order to help him flesh out his tunes with a simple accompaniment.

This included composers George Botsford, George Meyer and Edgar Leslie. Cliff, however, was the first of a handful of assistants hired specifically to be at Berlin's bidding whenever the muse struck. There was probably a little more to Berlin's need to have Hess around, since he had recently lost his first wife, Dorothy Goetz, sister of lyricist E. Ray Goetz, just months after they had married. It would be understandable that the grieving Berlin would want company to keep him distracted. To that end, Hess actually took up residence in Berlin's apartment, and when he wasn't assisting Irving with his latest song, perhaps deciding on the chord progression for a verse or one specific chord change, or tending to the composer's business affairs, he could be heard performing on some of the New York stages, working as an accompanist for some singers, or even writing his own material. But Berlin was the first priority in his life at that time, for which he received an adequate stipend. The sometimes arduous process was described in an article by writer Rennold Wolf in the August, 1913, issue of Green Book Magzine:

|

Hess resides with Berlin at the latter's apartment in Seventy-first Street; he attends to the details of the young song-writers's business affairs, transcribes the melodies which Berlin conceives and plays them over and over again while the latter is setting the lyrics. When Berlin goes abroad Hess accompanies him.

Hess' position is not so easy as it might at first appear, for Berlin's working hours are, to say the least, unconventional. And right here is to be mentioned the real basis of Berlin's success. It is industry—ceaseless, cruel, torturing industry There is scarely a waking minute when he is not engaged either in teaching his songs to a vaudeville player, or composing new ones.

His regular working hours are from noon until daybreak. All night long he usually keeps himself a prisoner in his apartment, bent on evolving a new melody which shall set the whole world to beating time. Much of the night Hess sits by his side, ready to put on record a tune once his chief has hit upon it. His regular hour for retiring is five o'clock in the morning. He arises for breakfast at exactly noon. In the afternoon he goes to the offices of Watterson [sic], Berlin and Snyder and demonstrates his songs.

That Hess could, in some regards, be considered a co-composer of many of the fine Berlin tunes of 1913 to 1918 creates a question without an easy answer in most cases. Yes, he provided some of the harmonic content that supported the melodies, and may have even worked some lyrical alterations by suggestion. But, as with Irving's other long-term assistants, he was paid to write and advise, and the words and music were still Berlin's. Later case law would suggest otherwise, as there were rulings showing that the harmonic direction of a song, such as in the blues, could provide sufficient difference between similar melodic lines, so history would be in favor of Cliff and his successors as per that credit. In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them. In any event, Hess seemed content for a while, and was allowed some liberties during his tenure.

In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them. In any event, Hess seemed content for a while, and was allowed some liberties during his tenure.

In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them. In any event, Hess seemed content for a while, and was allowed some liberties during his tenure.

In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them. In any event, Hess seemed content for a while, and was allowed some liberties during his tenure.Some of their methodology was recounted in the first Berlin biography, As Thousands Cheer, written by Laurence Bergreen, echoing some British newspaper articles as well as an August 1913 edition of Variety and the July 12, 1913, edition of the Music Trade Review. Distilled down here is that one particular event in which Berlin was, in a sense, publicly exposed for his true abilities, and lack thereof, for the first time. Shortly after Cliff had been hired, Irving was invited to perform, as best he could, in London. As was customary for him, he held a press conference once arriving, which while decidedly an American custom and clearly not British, was still effective in getting him publicity. Since the audiences at the Hippodrome were limited, he felt that the exposure in the press would spread his name to more people in the United Kingdom. This one could have hurt his career. He admitted during the event that he could not read or write music, but with the help of his secretary he could still turn out fine songs in short order. To that end, he asked for a suggestion and got one. For the next hour, Irving worked on That Humming Rag, banging out notes with one finger, while Cliff endeavored to score the piece on the spot. By the end of the hour it was evident to the press that Hess might have been the real talent in the room, and some items were published suggesting that Berlin was perhaps not so talented after all, barely able to play and unable to notate. Some of the press was just matter of fact about it, such as in this description of the incident:

A musician sat at the piano. Mr. Berlin began to hum and to sway in the motion of ragtime. Round and round the room he went while the pianist jotted down the notes. Mr. Berlin stopped occasionally: "That's wrong, we will begin again." A marvelous ear, a more marvelous memory, he detects anything amiss in the harmony and he can remember the construction of his song from the beginning after humming it over once. The actual melody took him an hour. Then he began on the words. While he swayed with the pianist playing the humming gave way to a jumble of words sung softly. And out of the jumble came the final composition above. This is how most of his ragtime melodies have been evolved. For one melody he must cover several miles of carpet.

When trying to plan his performance and overcome any potential bad press all at once, Irving came to the conclusion that all of his material had already been spread around London, and that he needed something new as a diversion. With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.

With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.

With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.

With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.Cliff began to have his own voice in 1914, co-composing the vaudeville number Beets and Turnips with Fred Ahlert. From that point on he managed several of his own musical works every year, some of them even moderate hits. On June 19, 1915, Cliff was married to Canadian Dorothy H. Marosco, and established his own residence, while still working regularly with Berlin. He also took the occasional break from Irving, as evidenced by his known independent activities. This included a few more instrumentals issued by various publishing houses, ranging from his Doodle Bug Rag to a characteristic Hawai'ian number, a genre gaining some traction at that time. Hess was also one of the performers in the revue Stop! Look! Listen!, which debuted on Christmas Day, 1915, and ran for three months. In 1916 he produced a tango, Spanish Onion, and a moderate fox trot, Homesickness Blues. He also established his own office at the Strand Theater Building, still citing Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, who occupied that location, as his employers as of the first draft for World War I in June of 1917. The Hess household must have been bustling, as he listed himself as the sole supporter of not only his wife, but his mother-in-law, father and mother. Late in the year, Cliff got a flush job accompanying actress and singer Dorothy Jardon on a national wartime tour of vaudeville theaters, which lasted into the spring of 1918.

On His Own At Last

Around the time that Cliff ended his ongoing professional relationship with Berlin in the latter half of 1918, he had one parting shot, which was likely an homage to his now-former boss. Hess managed to turn out somewhat of a hit based on one of Berlin's biggest hits of the past decade, Alexander's Ragtime Band, with his own war-based number, When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band to France. Berlin moved on to using Arthur Johnson as his ghost writer throughout the 1920s, following Cliff's model for the most part. As for Hess, he teamed with a number of lyricists, not showing any particular allegiance to them, although appearing to favor Howard E. Johnson and Sidney D. Mitchell for a while following the Great War. The 1920 census had Cliff and Dorothy living in Manhattan, without all of the relations found in their apartment three years prior, and with Cliff listed as a songwriter with his own office. Now experience, and having made a name for himself, Hess was on the verge of another phase of his career.

Hess managed to turn out somewhat of a hit based on one of Berlin's biggest hits of the past decade, Alexander's Ragtime Band, with his own war-based number, When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band to France. Berlin moved on to using Arthur Johnson as his ghost writer throughout the 1920s, following Cliff's model for the most part. As for Hess, he teamed with a number of lyricists, not showing any particular allegiance to them, although appearing to favor Howard E. Johnson and Sidney D. Mitchell for a while following the Great War. The 1920 census had Cliff and Dorothy living in Manhattan, without all of the relations found in their apartment three years prior, and with Cliff listed as a songwriter with his own office. Now experience, and having made a name for himself, Hess was on the verge of another phase of his career.

Hess managed to turn out somewhat of a hit based on one of Berlin's biggest hits of the past decade, Alexander's Ragtime Band, with his own war-based number, When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band to France. Berlin moved on to using Arthur Johnson as his ghost writer throughout the 1920s, following Cliff's model for the most part. As for Hess, he teamed with a number of lyricists, not showing any particular allegiance to them, although appearing to favor Howard E. Johnson and Sidney D. Mitchell for a while following the Great War. The 1920 census had Cliff and Dorothy living in Manhattan, without all of the relations found in their apartment three years prior, and with Cliff listed as a songwriter with his own office. Now experience, and having made a name for himself, Hess was on the verge of another phase of his career.

Hess managed to turn out somewhat of a hit based on one of Berlin's biggest hits of the past decade, Alexander's Ragtime Band, with his own war-based number, When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band to France. Berlin moved on to using Arthur Johnson as his ghost writer throughout the 1920s, following Cliff's model for the most part. As for Hess, he teamed with a number of lyricists, not showing any particular allegiance to them, although appearing to favor Howard E. Johnson and Sidney D. Mitchell for a while following the Great War. The 1920 census had Cliff and Dorothy living in Manhattan, without all of the relations found in their apartment three years prior, and with Cliff listed as a songwriter with his own office. Now experience, and having made a name for himself, Hess was on the verge of another phase of his career.Even before the end of the war, consumers seemed more interested in popular music than ever, and manifested that interest in the purchase of phonographs and player pianos. To that end, they also needed a constant supply of content for these machines. Cliff was among those who was helping to provide both. His first known venture into recording did not turn out so great for unknown reasons. He accompanied the newly-formed duo of Blossom Seeley and Benny Fields, for whom he had been playing since early 1918, on two sides, one for each of them, at the Victor Studios in New York in December of 1919. Another one followed in March, 1920, with singer and cornetist Bob Miller. But none of them were ultimately released. There may have been simply a recording defect or a performance that had flaws and was not approved by the music director. He also made a handful of piano rolls for Vocalstyle around the same time, including the highly popular nonsense tune, Ja Da.

Cliff found a three new gigs in short order. First, he started working with the Leo Feist firm as a composer, arranger and promoter. Then, Cliff had got a taste of Broadway, or at least off-Broadway life, having worked with Joseph Santly on a number of small one-act musical comedies from 1920 into at least 1927, sometimes as lyricist and sometimes as music composer. Many of them yielded some usable published material. These were usually performed initially on the B.F. Keith vaudeville circuit, then later as independently produced by Santly. Hess would also write several fine short entertainments on his own, including On With the Dance in 1922. Finally, he got hired on in late 1919 with the MelODee piano roll company as a talent. His positions were highlighted in the March 20, 1920, edition of the Music Trade Review:

One of the popular and successful members of the Melodee music roll recording staff is Cliff Hess, a young musician and pianist of unusual ability, who is able to interpret the popular airs of the day on the player-piano in an individual yet musicianly style. Mr. Hess' recordings are constantly becoming more popular as their interesting character is more generally appreciated, and whether it is his playing of "Throw Out the Mason and Dixon Line" or some more serious work, his playing is right.

Mr. Hess, who as a song writer is associated with the professional studios of Leo Feist, Inc., has been in the music game for about ten years, coming to New York about five years ago as secretary for Irving Berlin, for whom he also arranged many numbers. He is responsible for such numbers as "Homesickness Blues," "Huckleberry Finn," "When Alexander Takes His Band to France," "I Used to Call Her Baby," "Heart-Breaking Baby Doll," etc. He has also had some experience in the production field, being associated with E. Ray Goetz in writing "Step This Way," for Lew Fields, and at the present time is responsible for the music of several tabloid musical comedies in vaudeville, among them Pat Rooney's "Rings of Smoke" and "Ye Song Shoppe."

In a short time, Cliff would take charge of MelODee's recording department, arranging for other artists, and cutting many fine renditions of popular tunes for the company as well over the next three years. He also continued his slow but steady output of compositions, coming up with The Boll Weevil Blues in 1921, and the novelty tune Corn on the Cob in 1923. Among his associates and friends were composer/pianists Zez Confrey and Frank E. Banta. They also toured parts of the United States promoting their music and recordings. In various pairings these fine pianists often performed piano duets at public events. Banta and Hess cut some sides for Columbia, OKeh and Vocalion Records. Cliff had the distinction of having made one of the earliest recordings of Banta's Upright and Grand in 1923 with The Ambassadors Orchestra, backed by his Corn on the Cob performed with Banta. There may be a few other recordings with Hess accompanying an artist, but they are hard to identify. Otherwise, he was primarily a soloist not a steady member of a recording dance band. Hess and Banta also collaborated on a few MelODee rolls. By this time, Cliff's publishing affiliation was with Jack Mills Music, who issued many famous novelty tunes of the 1920s.

Since 1920, both Banta and Hess had also been artists for DuoArt reproducing rolls, with which both had offered duets and many solo performances. But Cliff was inclined, as were many of his peers, towards the fast-growing medium of radio broadcasting, even to the point where he wrote a tune, Turn on Your Radio (And Listen In on Your Home Town), which Mills promoted as the "official song of radio broadcasting stations... [to be] used as an overture or opening song." It was successfully introduced by Ben Selvin and His Moulin Rouge Orchestra even before it was published. Cliff's indirect involvement with an affiliation between DuoArt's parent company Aeolian and growing electronics giant RCA was noted in a Music Trade Review article on May 5, 1924:

Following the appointment of the Aeolian Co. as distributor for the products of the Radio Corporation of America, regular programs by artists recording for the Duo-Art piano or Vocalion Red Records have been broadcasted from Station WJY operated by the Radio Corporation and located atop the Aeolian Hall. The first program was presented by Monroe Silver, the originator of the "Cohen" records, Irving Kaufman, the popular tenor, and Frank Banta and Cliff Hess, pianists. All four artists play for Vocalion records and the last two also record for Duo-Art rolls.

By the end of the year, Brunswick Records in Chicago would purchase Vocalion and Aeolian records from Aeolian, so Hess was more or less without his audio recording outlet, and went back to rolls and other pursuits. He would divide his time over the next several years between composing, writing the one-acts, and performing on the radio. The demand for piano rolls was diminishing as radio gained popularity, so there was not much of his playing found in that medium after 1925. The 1925 New York census and 1930 Federal enumeration both showed Cliff and Dorothy residing in their home in Flushing, Queens, on Long Island in New York. At some point over the next few years, Dorothy would disappear from Cliff's life, likely from a divorce given that she put the home up for sale in mid-1935. This was also a time of career transition, perhaps evolution, that would keep Hess busy for several more years.

The East Coast Hollywood Venture

The coming of sound to film was a boon to the industry between 1927 and 1929. However, since the technology had made it difficult to record dialog without extraneous noise, and since the public was thirsting for entertainment and spectacle to go with the sound, musicals were highly popular and somewhat profitable properties. By 1930, dramas, comedies, and even early horror films and serials were in production. However, musicals would not go so much out of style for the next three decades, even the lesser ones which were later known as B movies or second features.

While most films by the mid-1930s were being made in Hollywood, California, many were still produced in New York and New Jersey, primarily because there was still a lot of talent to be found there on the stage and in the recording studios. Cliff had picked up on this, and by 1931 his services as a composer and arranger were called upon to add musical highlights to either short musicals - twenty minutes to less than one hour in length - or even some comic shorts that only required one or two tunes. In fact, his initial plunge came when Warner Brothers needed a song in a hurry for the musical short Angel Cake, and they went to their music arm, Remick Music, who sent them to Cliff. He provided what they needed within an hour, relaying the final result over the telephone. His work with films really picked up in 1933, and while some of the work was done on the East Coast, Cliff had to take the occasional trips to Hollywood to do rewrites, and to work with other musicians involved with a project. It was a plum position for a less famous composer to be in during the Great Depression when work for many musicians and composers who had made their fame in the 1910s was hard to come by, particularly during the shift from early jazz to swing and blues. Hess managed to keep relatively busy into 1937, primarily writing for Vitaphone shorts produced by Warner Brothers. It is probable that not all of his work received proper credit during these years, so some projects he worked on remain an unknown quantity.

Fading From View and Legacy

Now divorced from Dorothy, Hess married again, probably in late 1935 or 1936. His second wife was Dorothea Deyo, sometimes understandably mistaken in the scant accounts of his life with his Canadian wife Dorothy. Dorothea was a decade younger than either Cliff or Dorothy. This was probably her second marriage as well. The 1940 census showed a daughter named Georgia, who had taken or was given Hess as her last name, and had been born in New Jersey around 1927. Cliff had also relocated to Readington, New Jersey, in the late 1930s. In the 1940 enumeration he still claimed work as a songwriter, as he did for the 1942 World War II Draft.

By this juncture, Cliff, now in his fifties, was not writing for films anymore, and other than a smattering of war-related tunes was also not really composing works for publication. His last writing partner was Abel Baer, with whom he had composed works from 1938 to 1943, then again in the early 1950s with a pair of semi-popular entries. Still, the 1950 enumeration, taken in East Orange, New Jersey, showed Cliff still declared as a songwriter in the enterainment business. Around 1953 or 1954, Cliff and Dorothea relocated to Brownsville, Texas. He passed on there in 1959 from congestive heart failure, less than two weeks before his 68th birthday. He was cremated and interred at Brookside Memorial Park in Brownsville. Dorothea followed Cliff to the cemetery in Houston in 1962, the victim of a malignant lymphoma.

The overall legacy of Cliff Hess is less that of a musical star and more of a background or middle tier musician. He was, however, an important component of the growth and evolution of popular music in the United States and the western world. His work was clearly part of the DNA of America's overall catalog, including many of Irving Berlin's compositions, and his piano rolls are still heard on digital recordings and YouTube videos. His cheery tunes brought, even if momentarily, a lightness to the heart of filmgoers at a time when the world seemed dark. Even his ragtime tunes, in small quantity, are performed a century and more later, inducing smiles. He was, in so many ways, the working man's musician.

Much of the content of this essay came from goverment records, sheet music, scattered discographies and rollographies, and a variety of periodicals and newspaper articles featuring or including Cliff Hess. Most good books on Irving Berlin, which also cite early magazines and newspapers, will mention Cliff, and are worth obtaining for even more information into the process and Tin Pan Alley in general. This includes Songs from the Melting Pot: The Formative Years and Irving Berlin, both by Charles Hamm. Corrections, comments, or additions to the lists at the left are welcomed. Just click on the author's head at the top of the window.