|

Charles Hunter (May 16, 1876 to January 23, 1906) | |

Compositions Compositions

| |

|

1899

Tickled to Death1900

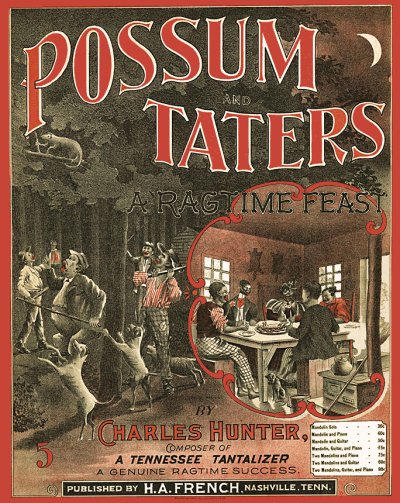

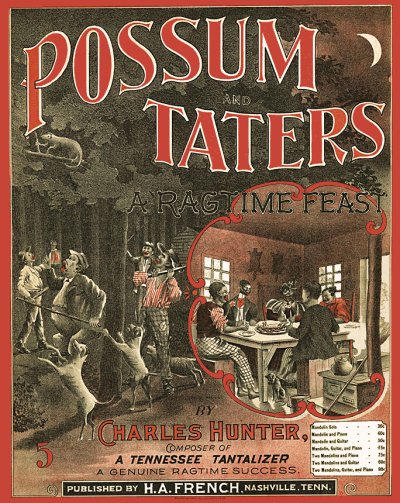

A Tennessee TantalizerPossum and Taters 1901

Cotton BollsQueen of Love 1902

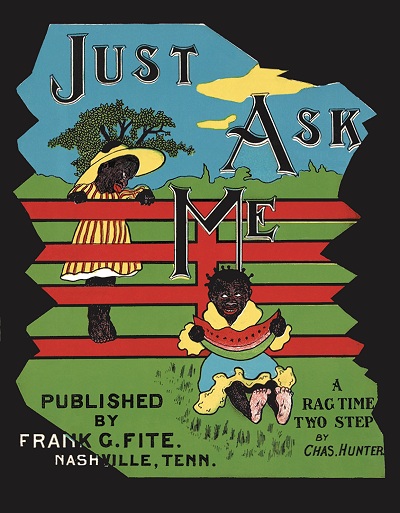

Just Ask Me |

1903

Why We Smile1904

Back to LifeJosephine (Opera) [1] Davy 1905

Seraphine Waltzes

1. w/W.V. Reynolds

|

Charles Hunter was born in Columbia, Tennessee, to saddle maker Jordan Hunter and his bride Fannie Hackney. He was one of five siblings, including Thomas (1867), Blanche (7/12/1868), James (1871) and Lena (1874). The 1880 census showed young Charlie as living in Columbia with his mother's parents, James and Isabell Hackney, his father Jordan, uncle William Hunter, and his older siblings. The fate of his mother is not known, but Jordan was listed as a widower. Charlie's blindness was not indicated on the census form, so it may have actually come soon after that rather than at birth as has often been reported. Growing up in an area that was full of talented black musicians, there was no shortage of aural folk influence for Hunter's keen ear to pick up. As a youth he was sent to the Nashville School for the Blind where sight-impaired students were taught trades, and of course how to blend into society as best they could.

As a youth he was sent to the Nashville School for the Blind where sight-impaired students were taught trades, and of course how to blend into society as best they could.

As a youth he was sent to the Nashville School for the Blind where sight-impaired students were taught trades, and of course how to blend into society as best they could.

As a youth he was sent to the Nashville School for the Blind where sight-impaired students were taught trades, and of course how to blend into society as best they could.The tall red-headed boy's natural acuity for the piano made him suitable to learn the trade of tuning, so he left the school prepared to pursue a career as a piano technician with the Jesse French Piano Company in Nashville. Although he had received little if any formal musical training during this time, Charles spent his free time creating at the piano, soaking in the influences of Nashville folk music from all races along with some of his own ideas. It is conceivable that his blindness helped shield him from some of the race issues that other white musicians sometimes encountered. However, in an area where little ragtime was being played and virtually none was published, it is a partial mystery as to where he learned the style so adeptly.

At the age of 23 his first rag, Tickled to Death, was published by Frank G. Fite of Nashville, as his employer was not in the publishing business. It quickly reached far beyond Tennessee in its overall popularity, and was frequently found on phonograph records and piano rolls throughout the ragtime era. Henry A. French, Nashville's largest publisher of that time, bought some of his subsequent works. French enjoyed great success with Hunter in his catalog, and invested well in the sheet music cover art for his works. In a 1903 article in the Music Trade Review, French made that success clear:

To show you how my publishing business is prospering... let me tell you that I recently gave an order for 35,000 copies of three different publications of mine - 'Possum and Taters,' 25,000, and 5,000 each of 'Tennessee Tantalizer' and 'Queen of Love' two-step. All of these numbers are by Charles Hunter. The order I have just placed makes a second edition of 5,000 each of 'Tantalizer' and 'Queen of Love' and a total of 40,000 copies of 'Possum and Taters.' ... This has been one of the best years I have ever known. I am very well satisfied with present conditions, and am sanguine as to the fall trade.

To show you how my publishing business is prospering... let me tell you that I recently gave an order for 35,000 copies of three different publications of mine - 'Possum and Taters,' 25,000, and 5,000 each of 'Tennessee Tantalizer' and 'Queen of Love' two-step. All of these numbers are by Charles Hunter. The order I have just placed makes a second edition of 5,000 each of 'Tantalizer' and 'Queen of Love' and a total of 40,000 copies of 'Possum and Taters.' ... This has been one of the best years I have ever known. I am very well satisfied with present conditions, and am sanguine as to the fall trade.In truth, those were substantial numbers at that time for instrumental pieces distributed by a Southern publisher, especially for a single composer.

The 1900 census showed Hunter in Nashville, Tennessee, boarding with the Thompkins family, his occupation listed as a piano tuner. In 1902, Charles was sent to St. Louis as a representative of French to bolster the piano operations in the firm's store there. One of the first notices of him in St. Louis was in the St. Louis Republic on January 2, 1903:

ATTRACTIVE PROGRAMMES. In the [Central Branch of the Y.M.C.A.] auditorium a programme of music and recitations began at 7:30 o'clock. The High School Glee Club sang several songs. Others on the programme were Miss Laura Lang and Miss Jenny May, who recited; Miss Maybelle H. Day, whistling soloist; Charles Hunter, pianist and vocalist, and Jerome Colona, violin solist.

Fite once again issued one of Hunter's more ambitious works, Just Ask Me. One of his last compositions was Back to Life, surprisingly picked up by a New York publisher, Charles K. Harris, late in the year, although ironically a bit close to his death. It may actually have been composed in response to the poor health Hunter had reportedly experienced for some time, and a partial recovery due to his altering his lifestyle in a positive manner. It had reportedly been compromised for some time in part because of many distractions he found in St. Louis. Being an anomaly of sorts among the pianists in the ragtime venues there, Hunter evidently found himself welcomed in many places, and took full advantage of the hospitality, often to the detriment of his job, although there is no mention of him ever playing in "colored bars" such as Turpin's Rosebud. As with many other performers who lived and played hard, the alcohol and carnal activity took a toll on his body. Trying to pull himself out of this destructive low point, Hunter managed to see the error of his ways and attempted to return to a healthier mode of living. On October 21, 1905 he was married to Estelle F. Inch. However, it was around this same that the tuberculosis that was starting to ravage his worn body was discovered. The disease finally took him on January 23, 1906, just 13 weeks after his marriage and a little short of his thirtieth birthday.

It may actually have been composed in response to the poor health Hunter had reportedly experienced for some time, and a partial recovery due to his altering his lifestyle in a positive manner. It had reportedly been compromised for some time in part because of many distractions he found in St. Louis. Being an anomaly of sorts among the pianists in the ragtime venues there, Hunter evidently found himself welcomed in many places, and took full advantage of the hospitality, often to the detriment of his job, although there is no mention of him ever playing in "colored bars" such as Turpin's Rosebud. As with many other performers who lived and played hard, the alcohol and carnal activity took a toll on his body. Trying to pull himself out of this destructive low point, Hunter managed to see the error of his ways and attempted to return to a healthier mode of living. On October 21, 1905 he was married to Estelle F. Inch. However, it was around this same that the tuberculosis that was starting to ravage his worn body was discovered. The disease finally took him on January 23, 1906, just 13 weeks after his marriage and a little short of his thirtieth birthday.

It may actually have been composed in response to the poor health Hunter had reportedly experienced for some time, and a partial recovery due to his altering his lifestyle in a positive manner. It had reportedly been compromised for some time in part because of many distractions he found in St. Louis. Being an anomaly of sorts among the pianists in the ragtime venues there, Hunter evidently found himself welcomed in many places, and took full advantage of the hospitality, often to the detriment of his job, although there is no mention of him ever playing in "colored bars" such as Turpin's Rosebud. As with many other performers who lived and played hard, the alcohol and carnal activity took a toll on his body. Trying to pull himself out of this destructive low point, Hunter managed to see the error of his ways and attempted to return to a healthier mode of living. On October 21, 1905 he was married to Estelle F. Inch. However, it was around this same that the tuberculosis that was starting to ravage his worn body was discovered. The disease finally took him on January 23, 1906, just 13 weeks after his marriage and a little short of his thirtieth birthday.

It may actually have been composed in response to the poor health Hunter had reportedly experienced for some time, and a partial recovery due to his altering his lifestyle in a positive manner. It had reportedly been compromised for some time in part because of many distractions he found in St. Louis. Being an anomaly of sorts among the pianists in the ragtime venues there, Hunter evidently found himself welcomed in many places, and took full advantage of the hospitality, often to the detriment of his job, although there is no mention of him ever playing in "colored bars" such as Turpin's Rosebud. As with many other performers who lived and played hard, the alcohol and carnal activity took a toll on his body. Trying to pull himself out of this destructive low point, Hunter managed to see the error of his ways and attempted to return to a healthier mode of living. On October 21, 1905 he was married to Estelle F. Inch. However, it was around this same that the tuberculosis that was starting to ravage his worn body was discovered. The disease finally took him on January 23, 1906, just 13 weeks after his marriage and a little short of his thirtieth birthday.Less than a month after Hunter's death a curiosity was introduced. In the February, 1906, issue of the Intermezzo magazine issued by publisher John Stark, a work was included titled Davy, "from the Opera (Josephine)." It showed Hunter as the composer of this tune, set to lyrics by W.V. Reynolds, and arranged by St. Louis composer David Socrates DeLisle. It is little more than a mildly syncopated strophic song, but the lyrics refer directly to the 1904 Lewis and Clark Exposition (World's Fair). This led to the discovery that a copy of the entire opera, listed with music by Hunter and words by Reynolds, was copyrighted in 1904, and a manuscript currently resides at the Unversity of Missouri Columbia, although in microfilm form. This further indicates that the production was originated by George S. Hill. There is still no evidence of a performance, but that at least one of the pieces was typeset is an indication of intent. More of this work will be explored in the near future.

I would like to add a personal note of thanks to Barry Morgan who sent information on Hunter's marriage certificate and obituary. He had also mentioned the possibility of the song, Davy, composed for the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. Performer/Historian Vincent Johnson managed to send along a scan of that piece, which led to other discoveries as of November, 2017. More will be presented when it becomes available.