William John Donaldson (April 21, 1891 to December 16, 1954) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1915

When You Sit Beside the Fireside in Winter [1]1916

Cold TurkeyThe Original Chateau Three Step Prepare the Eagle to Protect the Dove (That's the Battle Cry of Peace) [1] 1917

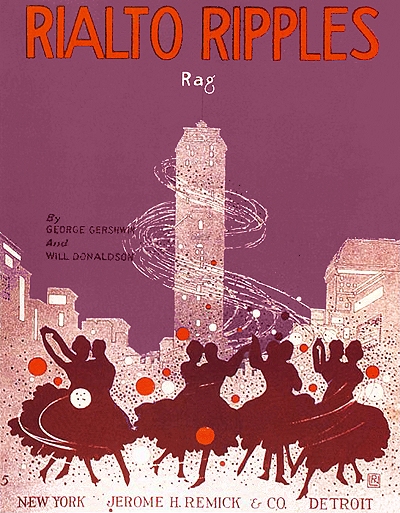

Rialto Ripples: Rag [2]Are We Downhearted? No! No! No! [3] There's a Little Bit of Green in Everybody [3] 1919

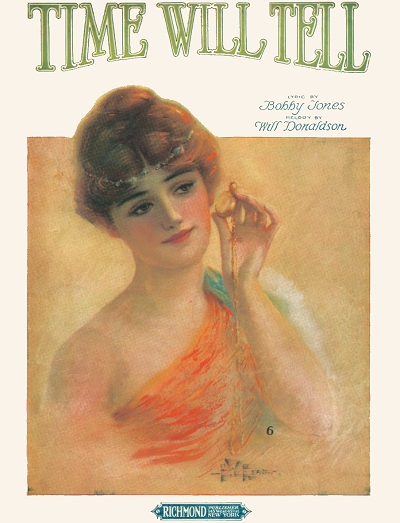

Play Me That Tune (Ya-Da-De-Dum-Dum) [4]China Dragon Blues [4] Good-Bye Pal [4] All That I Know of Love (I Learned from You) [5] Everybody's Crazy Over Dixie [5,6] Time Will Tell [6] 1920

A Trip to Hitland: Musical [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]Laughing Vamp Underneath the Skies (of Home Sweet Home) I'm Telling You You're Just Around the Corner from Heaven (When You're Just Around the Corner from Home) We Will Still Be Together (You and I) Scissors Wow Think of Me (I'll Think of You) 1921

Tell Her at Twilight [9]Write and Tell Your Mammy I'm Coming [9,10] 1922

Cannibola [10,14]1923

How Stayed to Cheer Mrs. Paul Revere whenPaul Revere Rode Away? When You Come to the End of the Lane [10] Oh! How She Lied to Me [17] Oh Sister, Aint' That Hot [17] I Don't Know Nobody, and Nobody Knows Me [18] Love Ain't Blind No More [18] Won't You Be My Sweet Man [18] Rainy Nights [18] Childhood Blues [19] 1924

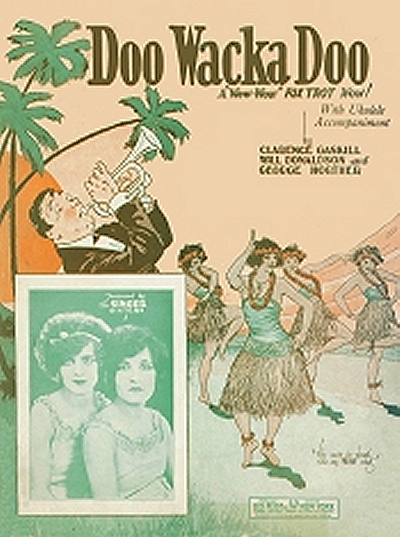

Down in Charleston: Charleston WaltzDown in Wah-Wah Town [11,20] In the Shade of Her Parasol [17] Doo Wacka Doo [20,21] Come Back to Me (When they Throw You Down) [22] Tell Me if You Know (Here is Question Number One) [23] 1925

When I Got Home This Ev'ning She WasThere [20] 1926

The Cohens and KellysStep on the Blues [24] 1927

Le Reve de L'Apache (The Apache's Dream)Rhapsody for Saxophone Gold Digger [25] Why Can't We Be Sweethearts All Over Again? [26] I've Got the Eggs in the Nest (And the Nest All Feathered for You) [10,27] How Ya Gonna Keep Your Wig Warm in a Wigwam When it Ain't Warm in the Wintertime?) [10,28] South Wind [10,29] |

1928

The Dark MadonnaDanse Barbare Speed Maniacs Chevrons: March Gorgonzola Stone Mountain Black Jack: March Piggly Wiggly Sultan of Swat: Baseball One-Step 1929

Hurrah for the Wonder Bakers! Yo-Ho!Yo-Ho! Yo-Ho! [30] 1937

Come to the Barn [31,32]We're On Our Way [31,32] Life is Sweet Again [33,34] 1938

March Moderne1940

I Can't Resist You [33]1941

Spellbound [33]Uncertain/ASCAP

Onions Bring Memories of YouI Gave You a Rose by the River of Dreams Femmes Qui Sont Ici Les [35] Mon Coeur est a Barcelona [36] Ne Cherchez Pas C'est l'Amour [37]

1. w/Harry T. Bunce

2. w/George Gershwin 3. w/Ray Sherwood 4. w/Irving Caesar 5. w/Rubey Cowan 6. w/Bobby Jones 7. w/Leon Flatow 8. w/Jimmy Brown 9. w/Bernie Grossman 10. w/Billy Frisch 11. w/Nat Vincent 12. w/Billy Baskette 13. w/Sam Ehrlich 14. w/Al Siegel 15. w/Ted Shapiro 16. George Fairman 17. w/Harry White 18. w/Joseph H. "Jo" Trent 19. w/Ed Porray & Irving Bibo 20. w/Clarence Gaskill 21. w/George Horther 22. w/Billy Rose 23. w/Al Koppel 24. w/Con Conrad & Otto Harbach 25. w/Edward "Duke" Ellington 26. w/Jan Barger, Charlie Warren & Roy Turk 27. w/Jack Meskill 28. w/Billy Hueston 29. w/Alfred Solman 30. w/Frank Moulan 31. w/Muriel "Molly" Pollock Donaldson 32. w/Madge Tucker 33. w/Ned Wever 34. w/Harold Lambert 35. w/Paule Emile G. Briollet & Paul Auguste Van Trappe 36. w/Marcel Israel & Joseph A. Vincentelli 37. w/Andre Despax Louis & Lucien Pierre Paul Rives |

Known Rollography Known Rollography | |

|

1916

Cold Turkey - One Step [Will Donaldson] - Uni-Record 202827Adeste Fideles [Trad] Assisted by E. Bergeson "with Beautiful Chime Effects" - Connorized 10276 1919

Everbody's Crazy Over Dixie [Jones/Donaldson/Cowan] - Rythmodik Song Roll J104393 | |

Will Donaldson had a hand in the start of a career of one of the great American composers, but in the end did not do too badly for himself either. Born in New York to hotel keeper John Henry Donaldson and his wife Rosanna Teresa "Rose" Riley, Will was the youngest of their three surviving children out of five. He had two older sisters, Beatrice (6/1879) and Agnes (2/1883). An older brother, Edward (10/1880), died in his early twenties. By the time of the 1900 census, John had become a shipping clerk, a position he would remain in for the rest of his life. Will's early musical training went beyond normal New York School System classes, as he attended the Pratt Institute, and was a part of the recently formed Art Students League.

Will's early musical training went beyond normal New York School System classes, as he attended the Pratt Institute, and was a part of the recently formed Art Students League.

Will's early musical training went beyond normal New York School System classes, as he attended the Pratt Institute, and was a part of the recently formed Art Students League.

Will's early musical training went beyond normal New York School System classes, as he attended the Pratt Institute, and was a part of the recently formed Art Students League.By 1910 Will, still living with his family in Brooklyn, was working as a theater pianist, playing for the early Ziegfeld star Elizabeth Brice (no relation to Fannie Brice) and Adele Rowland among others. Within a few years he also accompanied early superstar Elsie Janis when she was in London in the mid-1910s. Will started making his way through both Vaudeville and movie houses over the next several years. He started arranging and producing piano rolls in 1915, and one of his first compositions appeared that same year, with more in 1916. Will he soon had a job as arranger and plugger with Jerome H. Remick and J.B. Haviland, perhaps in a free-lance capacity. His 1917 draft record showed him to be a composer with Haviland as his employer, and also indicated poor eyesight as a handicap that likely kept him out of the trenches in World War I.

While at Remick, Donaldson met and befriended 16-year-old George Gershwin who had been hired the prior year as a song plugger. Gershwin had repeatedly been thwarted in his efforts to get his employer, or more directly manager Mose Gumble, to do anything with his own compositions. Donaldson helped him in some way with George's only rag, Rialto Ripples, making it the sole Remick publication of a Gershwin tune at that time. Will's role is unclear, whether it be as an arranger making the piece playable for the average player, or actually adding some content to the challenging work. In any case, he got co-credit for the rag, and Gershwin got the boot soon after by Gumble who made it clear he should "leave composing to the composers." [Gumble later conceded that this was far from one of his finest decisions.] Donaldson was a friend and admirer of Gershwin for many years thereafter, as noted in later correspondence between the two men.

[Gumble later conceded that this was far from one of his finest decisions.] Donaldson was a friend and admirer of Gershwin for many years thereafter, as noted in later correspondence between the two men.

[Gumble later conceded that this was far from one of his finest decisions.] Donaldson was a friend and admirer of Gershwin for many years thereafter, as noted in later correspondence between the two men.

[Gumble later conceded that this was far from one of his finest decisions.] Donaldson was a friend and admirer of Gershwin for many years thereafter, as noted in later correspondence between the two men.Having proven himself as a capable song writer, in addition to composing some interesting instrumentals, one being the well regarded syncopated waltz The Original Chateau Three Step, Donaldson was readily able to get music into print for several years. However, he was also a very capable pianist, and did some audio recordings for a couple of companies, including Edison's Diamond Disc label. Even before he was in print, at some point around 1915 Will started working with Rythmodik Music Corporation, a branch of the Aeolian Piano Roll Company. According to roll historian Robert Perry there is a good chance Will was on staff, as his name showed up on a number of "hand-played" rolls in the capacity of arranger or perhaps third hand; "Assisted by W.E.D." [which might also indicate fellow composer Walter Donaldson]. For his first two years this was pretty much exclusively applied to rolls recorded by Pete Wendling, but by the time Aeolian dropped their Rythmodik line in late 1920 he had appeared with other artists as well. Only one Rythmodik roll credits him as the sole artist, playing his own piece Everybody's Crazy Over Dixie in 1919. One of the people he likely met during these years was artist Muriel Pollock who would become his wife around 1933. There is no indication he was ever involved in the creation or editing of her piano roll performances.

As of 1920 Will was still living with his mother Rose and sister Beatrice, listed simply as a composer of music. It was in this year that a number of New York songwriters, including publisher Ted Shapiro and lyricists Nat Vincent and Billy Baskette pooled their talent into a stage show called A Trip to Hitland. The sheet music shows anywhere from eight to ten names for composer credit on each piece. In spite of the title, it turned out no hits. After a couple of dry years, Will had a strong showing in 1923, the same year that he joined ASCAP, which had been founded in 1914. In addition to working with Joseph "Jo" Trent on pieces that would be included at one point or another in the hit musical Runnin' Wild, which introduced the Charleston into the world, he co-wrote Oh Sister, Ain't That Hot, which became a substantial jazz age hit still performed and recorded in the 21st century.

The following year Will took a 1920s catch phrase and with a couple of lyricists turned it into another hit, Doo Wacka Do, a term that eventually became as annoying to some as "vo-de-o-do" due to its frequent usage. Around 1926, Will, who had been a movie pianist off and on, started composing some works specifically for film performance, including one for what became a series spanning silent and sound films, The Cohens and Kellys. Some of his works were spread out over a series of folios released in 1928. In 1927, and some historians speculate even earlier, he co-composed a tune with Duke Ellington called The Gold Digger, part of the Ellington standard playbook for many years. One group that Donaldson was briefly involved with was the Edisongsters, a male trio with Will as the accompanist and arranger. They were broadcast as an Edison Radio presentation every Monday evening. The singers were Jack Parker, Frank Luther and Phil Dewey. Another group active into the 1930s was the Men About Town, for which he performed and ultimately created over 2000 vocal arrangements.

Around 1926, Will, who had been a movie pianist off and on, started composing some works specifically for film performance, including one for what became a series spanning silent and sound films, The Cohens and Kellys. Some of his works were spread out over a series of folios released in 1928. In 1927, and some historians speculate even earlier, he co-composed a tune with Duke Ellington called The Gold Digger, part of the Ellington standard playbook for many years. One group that Donaldson was briefly involved with was the Edisongsters, a male trio with Will as the accompanist and arranger. They were broadcast as an Edison Radio presentation every Monday evening. The singers were Jack Parker, Frank Luther and Phil Dewey. Another group active into the 1930s was the Men About Town, for which he performed and ultimately created over 2000 vocal arrangements.

Around 1926, Will, who had been a movie pianist off and on, started composing some works specifically for film performance, including one for what became a series spanning silent and sound films, The Cohens and Kellys. Some of his works were spread out over a series of folios released in 1928. In 1927, and some historians speculate even earlier, he co-composed a tune with Duke Ellington called The Gold Digger, part of the Ellington standard playbook for many years. One group that Donaldson was briefly involved with was the Edisongsters, a male trio with Will as the accompanist and arranger. They were broadcast as an Edison Radio presentation every Monday evening. The singers were Jack Parker, Frank Luther and Phil Dewey. Another group active into the 1930s was the Men About Town, for which he performed and ultimately created over 2000 vocal arrangements.

Around 1926, Will, who had been a movie pianist off and on, started composing some works specifically for film performance, including one for what became a series spanning silent and sound films, The Cohens and Kellys. Some of his works were spread out over a series of folios released in 1928. In 1927, and some historians speculate even earlier, he co-composed a tune with Duke Ellington called The Gold Digger, part of the Ellington standard playbook for many years. One group that Donaldson was briefly involved with was the Edisongsters, a male trio with Will as the accompanist and arranger. They were broadcast as an Edison Radio presentation every Monday evening. The singers were Jack Parker, Frank Luther and Phil Dewey. Another group active into the 1930s was the Men About Town, for which he performed and ultimately created over 2000 vocal arrangements. In the late 1920s and later Will was working as a voice coach for radio artists, and was also involved with either writing commercial jingles or adapting them. Among them was a song for the Wonder Bread company used often on the radio. ASCAP records indicate, although it is hard to confirm for certain, that he likely adapted the popular song Mm Mm Good into the well known jingle used to this day by Campbell Soups. Donaldson had gotten married to Josephine Plant around 1926. However, the 1930 enumeration showed him lodging in Manhattan alone. As it turns out, Josephine was ill for some time, and lost her battle on December 27, 1933. It is unclear, however, if they were still married at that time. It appears that he married his musical sweetheart Muriel Pollock around 1933. Their son Theodore D. "Ted" Donaldson who was born in August, presumably in 1933, so possibly before or around the time they were married. This distinction remains unclear in the research.

Will, like Muriel, traveled back and forth for a few years between Hollywood and New York, depending on the type of engagements they were needed for. However, with a regular radio broadcast and Broadway appearances, many with her musical "Lady Bug" partner Vee Lawnhurst, Muriel was mostly grounded in New York City for the decade. The 1940 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed the couple and their son living on West 55th, both listed as musicians working in broadcasting. With Muriel he wrote The Boys and Girls Quiz Book in 1940. Will's 1942 draft card, also taken in Manhattan, showed him working for Air Features Incorporated (AFI), a clearing house and distribution arm of the American Federation of Radio Artists which would later become AFTRA. Around 1942 or 1943 the Donaldsons relocated to California for good, and Will became known as a vocal coach for the Hollywood studios, as well as finding work with both movie and recording studios. Even the Donaldson's son Ted had become a stage and radio actor when he was four in New York, eventually appearing in some movies as a talented child performer. His big screen debut was with Cary Grant in 1943. The family lived at 1422 N. Alta Vista Blvd. in Los Angeles throughout most of the 1940s and 1950s.

After the war Will spent his remaining years living in Hollywood. The 1950 enumeration showed no occupation for Muriel, while Will was teaching in a voice studio, and Ted was regularly acting in radio shows. Will passed on at the end of 1954. On July 1, 1955, Muriel and Ted donated the Will Donaldson Collection of Theodore Drieser Books and Manuscripts to the UCLA Special Collections Department. Muriel survived Will until 1971 when she died at age 76. Thanks to sheet music and the magic of piano rolls, records and films, the important legacy of Will and Muriel remains with us.

Thanks go to New Zealand piano roll historian Robert Perry who contributed information on Donaldson's involvement with Rythmodik.