Polly Adelaide Hendricks Hazlewood (Del Wood) (February 22, 1920 - October 3, 1989) | |||

Compositions Compositions | |||

|

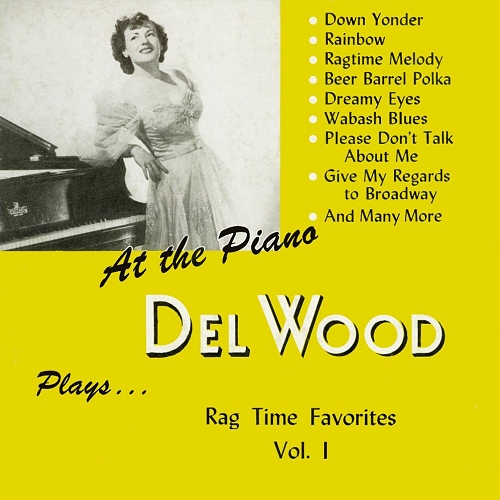

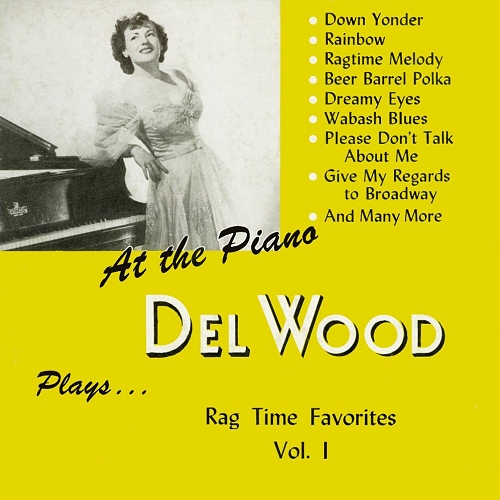

1951

Ragtime Melody [1,2]Runaround 1952

Pickin' and Grinnin'1955

Ivory Corn1956

Gismo Rag1957

Whirl-A-Way |

1958

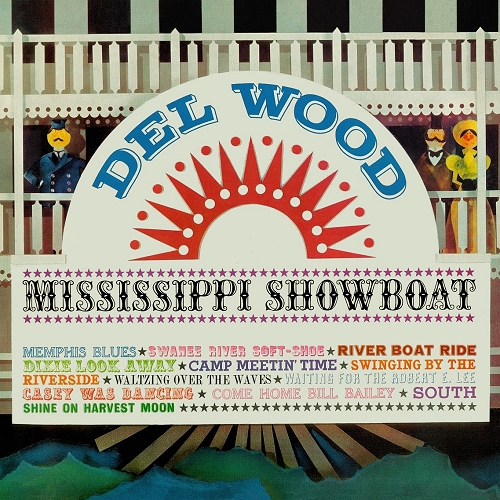

River Boat RideRidin' High 1959

SpeakeasyVarsity Trot Raggin' the Keys What's the Password

1. w/William Beasley

2. w/Dick Stratton | ||

Discography Discography | |||

| |||

Del Wood actually started out life as Polly Adelaide Hendricks on February 22, 1920. Born to iron worker John N. Hendricks and Nellie (Hough) Hendricks, she was the oldest of three girls, including sisters Emily and Margaret, and named after her maternal grandmother. In 1920 the couple was shown living a mile or so outside of incorporated Nashville, Tennessee in rural Davidson County, with John using the name William, perhaps his original given name. Within a couple of years they would appear in the greater Nashville area. On Polly's fifth birthday the family purchased a piano for her to learn on, and she took to it immediately. After three months of lessons it was deemed more logical to wait on those until she could read and write more fluently. Once she was eight and for several years after that she had formal lessons and learned classical music, along with technique, harmony and theory. The Hendricks family was shown in Nashville, Tennessee in the 1930 census with John working as a streetcar conductor. While he owned his home, the family did not have a radio set at this time, but they did have a crystal headphone set. The Hendricks likely had a radio soon enough, as radio would play an important role in Polly's development and desires.

On Polly's fifth birthday the family purchased a piano for her to learn on, and she took to it immediately. After three months of lessons it was deemed more logical to wait on those until she could read and write more fluently. Once she was eight and for several years after that she had formal lessons and learned classical music, along with technique, harmony and theory. The Hendricks family was shown in Nashville, Tennessee in the 1930 census with John working as a streetcar conductor. While he owned his home, the family did not have a radio set at this time, but they did have a crystal headphone set. The Hendricks likely had a radio soon enough, as radio would play an important role in Polly's development and desires.

On Polly's fifth birthday the family purchased a piano for her to learn on, and she took to it immediately. After three months of lessons it was deemed more logical to wait on those until she could read and write more fluently. Once she was eight and for several years after that she had formal lessons and learned classical music, along with technique, harmony and theory. The Hendricks family was shown in Nashville, Tennessee in the 1930 census with John working as a streetcar conductor. While he owned his home, the family did not have a radio set at this time, but they did have a crystal headphone set. The Hendricks likely had a radio soon enough, as radio would play an important role in Polly's development and desires.

On Polly's fifth birthday the family purchased a piano for her to learn on, and she took to it immediately. After three months of lessons it was deemed more logical to wait on those until she could read and write more fluently. Once she was eight and for several years after that she had formal lessons and learned classical music, along with technique, harmony and theory. The Hendricks family was shown in Nashville, Tennessee in the 1930 census with John working as a streetcar conductor. While he owned his home, the family did not have a radio set at this time, but they did have a crystal headphone set. The Hendricks likely had a radio soon enough, as radio would play an important role in Polly's development and desires.A native and lifetime resident of Nashville, Polly was surrounded by the influences of early country music and the remaining vestiges of ragtime, particularly through the guitar pickers. In spite of her parent's best efforts to encourage a direction towards classical music, the environment in Nashville, plus the early local programming on radio, convinced the teenager that she wanted to play piano in the honky-tonk style. Her dream goal was the Grand Ole Opry, something she would eventually realize in her early 30s. As she later remarked in a 1984 interview, "The classics are such that you are playing someone else's material and you must play them perfectly. In ragtime, you can give it your own interpretation. To me, ragtime and country music are the only true American music forms we have. Ragtime has so much get-up-and-go that it's infectious; it's part of our heritage."

In Nashville directories throughout the 1930s and into the early 1940s, John appeared as a motorman or car operator for the Tennessee Electric and Power Company. In the 1940 census he is listed also as working as a street car operator, employed by the light plant of Nashville (likely the power source). The family lived from the late 1920s through at least 1941 at 1619 Lillian Street just across the Cheatham Lake channel from downtown Nashville. As of 1942, John, now a bus driver, and Nellie were residing a few blocks north at 1036 Eastland Avenue, with only one child left living with them. Polly had moved out by the time of the 1940 enumeration (her whereabouts are uncertain for that record), and in 1941 she was married to Tennessee native Carson Hazlewood (many sources show Hazelwood, but official records use Hazlewood), who was the son of a rural blacksmith. The 1942 Nashville directory shows the couple living in the rear of her parent's home, with Carson employed as sheet metal worker for Tennessee Aircraft Inc., likely turning out defense equipment for the war.

One of Polly's early jobs was selling sheet music as a demonstrator and working in a record store. Shortening her middle and married names (Adelaide Hazlewood) to something easier to remember (and intentionally non-gender specific), Polly adopted Del Wood for the purpose of performance and composition. Del specifically noted that having sold records for many years, she found that women purchased a large number of them, and that they were more inclined to pick those recorded by men. Having a potentially male name did cause a few mix-ups and issues over the years, but she stuck with it. Del started banging around in bands and honky-tonk joints in her 20s. After the war, Carson was seen working as a mechanic for Motor Body Service, but Del, shown this time as Adelaide instead of Polly, did not have an occupation listed. Her father was still driving a bus, but the Hazlewoods no longer lived with her parents.

Del started banging around in bands and honky-tonk joints in her 20s. After the war, Carson was seen working as a mechanic for Motor Body Service, but Del, shown this time as Adelaide instead of Polly, did not have an occupation listed. Her father was still driving a bus, but the Hazlewoods no longer lived with her parents.

Del started banging around in bands and honky-tonk joints in her 20s. After the war, Carson was seen working as a mechanic for Motor Body Service, but Del, shown this time as Adelaide instead of Polly, did not have an occupation listed. Her father was still driving a bus, but the Hazlewoods no longer lived with her parents.

Del started banging around in bands and honky-tonk joints in her 20s. After the war, Carson was seen working as a mechanic for Motor Body Service, but Del, shown this time as Adelaide instead of Polly, did not have an occupation listed. Her father was still driving a bus, but the Hazlewoods no longer lived with her parents.After a decade of building repertoire and reputation, Del spent some time as a staff pianist at WLBJ in Bowling Green, Kentucky, while maintaining her job working as a payroll clerk for the Tennessee Department of Health. Her first recordings were done in a non-union studio above a grocery store playing piano for various artists. One evening one of the recording session was interrupted by a visit from the local police department. They were under the impression that the room was being used as a brothel, and left rather embarrassed when they discovered nothing but musicians and microphones. The 1950 census showed Adelaide and Carson living just outside of Nashville. He was listed as a mechanic for a bus company, and despite her claims of a state job (the timing is uncertain), Del was shown as a saleslady in a department store, possibly one of her side gigs.

It was at WLBJ that Del was heard playing Down Yonder among other pieces, which led to a gig with a recording group called Hugh `Baby' Jarrett and his Dixieliners. The pianist who was to come to one of their late 1950 sessions did not show up, evidently due to a hangover, so Del was called in on short notice to handle keyboard duties for the recording. She did not know the song Little Liza Jane which they wanted to record, so instead went ahead with the more familiar Down Yonder among the other cuts at the session. While not the first piece of hers released by the label, it would be the most notable one when it finally escaped the studio in 1951.

This event led to the first of many recording sessions for the Tennessee Records label featuring Del starting in late 1950, eventually allowing her to quit her job and pursue the long-held dream. Down Yonder soon became a national hit in both the Country and Pop categories in Billboard, and is considered to be the first million-selling record by a female artist, and possibly the first million selling instrumental out of Nashville. She later asserted that even in the 1940s, "a lot of Nashville people weren't too proud of country music. They had their nose in the air and it was the highbrow stuff regardless of it was music or what else. It was the city of colleges, the city of churches, everything but country music." Once Nashville became "Music City U.S.A." the local attitude changed considerably. It is important to note that until the late 1940s, the majority of labels in the recording business were in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. There were many independents in the area, but little commercial recording activity in Nashville.

Why did Down Yonder become such a hit? Singer Al Jolson who could sell almost anything had trouble making much headway with this piece. Composed in 1921 by L. Wolfe Gilbert, it was not only an intended follow up to Waiting for the Robert E. Lee which he co-wrote with Lewis F. Muir in 1912, but actually stole some lines outright from the earlier song. But it simply did not get much play, being a ragtime song introduced in the jazz era. However, Wood was able to exploit it with a unique hybrid sound of country and ragtime that resonated at the beginning of a massive nostalgic musical revival in the United States. It didn't hurt that airplay on Nashville station WSOK, which reached most of the eastern half of the country, mixed it in with other cuts from Tennessee, Bullet, Cherokee, and assorted local labels. This is important because of the mix of not only country music, but also black rhythm and blues in a time before Motown and rock and roll, and even before the Chess and Sun labels were in full swing. So all types of music lovers heard it. This was also a transitional time in music when the Swing Era was long over but Rock and Roll was still finding a voice. People wanted some alternative to Be Bop or forms of music harder to access, which meant everything from Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford to Pee Wee Hunt and, yes, Del Wood.

Composed in 1921 by L. Wolfe Gilbert, it was not only an intended follow up to Waiting for the Robert E. Lee which he co-wrote with Lewis F. Muir in 1912, but actually stole some lines outright from the earlier song. But it simply did not get much play, being a ragtime song introduced in the jazz era. However, Wood was able to exploit it with a unique hybrid sound of country and ragtime that resonated at the beginning of a massive nostalgic musical revival in the United States. It didn't hurt that airplay on Nashville station WSOK, which reached most of the eastern half of the country, mixed it in with other cuts from Tennessee, Bullet, Cherokee, and assorted local labels. This is important because of the mix of not only country music, but also black rhythm and blues in a time before Motown and rock and roll, and even before the Chess and Sun labels were in full swing. So all types of music lovers heard it. This was also a transitional time in music when the Swing Era was long over but Rock and Roll was still finding a voice. People wanted some alternative to Be Bop or forms of music harder to access, which meant everything from Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford to Pee Wee Hunt and, yes, Del Wood.

Composed in 1921 by L. Wolfe Gilbert, it was not only an intended follow up to Waiting for the Robert E. Lee which he co-wrote with Lewis F. Muir in 1912, but actually stole some lines outright from the earlier song. But it simply did not get much play, being a ragtime song introduced in the jazz era. However, Wood was able to exploit it with a unique hybrid sound of country and ragtime that resonated at the beginning of a massive nostalgic musical revival in the United States. It didn't hurt that airplay on Nashville station WSOK, which reached most of the eastern half of the country, mixed it in with other cuts from Tennessee, Bullet, Cherokee, and assorted local labels. This is important because of the mix of not only country music, but also black rhythm and blues in a time before Motown and rock and roll, and even before the Chess and Sun labels were in full swing. So all types of music lovers heard it. This was also a transitional time in music when the Swing Era was long over but Rock and Roll was still finding a voice. People wanted some alternative to Be Bop or forms of music harder to access, which meant everything from Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford to Pee Wee Hunt and, yes, Del Wood.

Composed in 1921 by L. Wolfe Gilbert, it was not only an intended follow up to Waiting for the Robert E. Lee which he co-wrote with Lewis F. Muir in 1912, but actually stole some lines outright from the earlier song. But it simply did not get much play, being a ragtime song introduced in the jazz era. However, Wood was able to exploit it with a unique hybrid sound of country and ragtime that resonated at the beginning of a massive nostalgic musical revival in the United States. It didn't hurt that airplay on Nashville station WSOK, which reached most of the eastern half of the country, mixed it in with other cuts from Tennessee, Bullet, Cherokee, and assorted local labels. This is important because of the mix of not only country music, but also black rhythm and blues in a time before Motown and rock and roll, and even before the Chess and Sun labels were in full swing. So all types of music lovers heard it. This was also a transitional time in music when the Swing Era was long over but Rock and Roll was still finding a voice. People wanted some alternative to Be Bop or forms of music harder to access, which meant everything from Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford to Pee Wee Hunt and, yes, Del Wood.The early recordings were usually done at either the WSM radio studio or in Tennessee Record's small studio. The company had been started by Alan Bubis, Reynold Bubis, Howard Allison and William Beasley in 1949, but not until Down Yonder did they have any hits of significance. The first cuts were pressed directly to 78 RPM records on a lathe, but by 1952 Del and others at Tennessee were recording to magnetic tape. Some of those early masters have deteriorated a great deal over the decades, so the early 33 1/3 and 45 RPM records remain the best sounding source of those early days. Along the way, Del started composing some of her own pieces, including the catchy Ragtime Melody, which like Down Yonder had been covered by pianist Lou Busch on Capitol Records. In late 1951, to get around a conflict with the local union which had put them on the unfair list for violating work periods and wage scales, the owners shut down Tennessee Records. Union musicians such as Wood, who joined after her contract had been signed, were advised to do no further work for the company. Bubis and Beasley relocated their operation, signed a new union contract, and renamed their studio as Republic Records, trying to bring their biggest star back with them.

This began a bit of a mess for Wood and Republic. While Wood was not under contract, she cut four sides (possibly more) with Decca Records on March 29, 1952. The tracks went unissued for over a year. By early 1953, Del had been recording for Republic, and finally signed a contract with them on February 9. Later in the year, Decca, capitalizing on her growing success, released their four sides. Republic Records and Wood filed suit alleging that Decca was breaching her contract with Republic by releasing the sides, even though they were recorded before the Republic Records contract was signed. The crux of the complaint was whether or not Wood had violated her contract with Tennessee Records, even though it had been sidelined by the union. In the end, it was determined that her contract with Republic Records negated her earlier contract with Tennessee Records, and since as a member of the union she could not work for Tennessee Records from November 1951 on, no further harm could have been to the company while they were in violation or on the unfair list. In the first judgment rendered in February, 1954, Republic was awarded $46,455.04 by the courts. However, on appeal, the suit against Decca was finally dismissed in 1956 by the United States 6th Circuit Court of Appeals as ultimately being without merit given the absence of proven harm during the contract dispute.

The crux of the complaint was whether or not Wood had violated her contract with Tennessee Records, even though it had been sidelined by the union. In the end, it was determined that her contract with Republic Records negated her earlier contract with Tennessee Records, and since as a member of the union she could not work for Tennessee Records from November 1951 on, no further harm could have been to the company while they were in violation or on the unfair list. In the first judgment rendered in February, 1954, Republic was awarded $46,455.04 by the courts. However, on appeal, the suit against Decca was finally dismissed in 1956 by the United States 6th Circuit Court of Appeals as ultimately being without merit given the absence of proven harm during the contract dispute.

The crux of the complaint was whether or not Wood had violated her contract with Tennessee Records, even though it had been sidelined by the union. In the end, it was determined that her contract with Republic Records negated her earlier contract with Tennessee Records, and since as a member of the union she could not work for Tennessee Records from November 1951 on, no further harm could have been to the company while they were in violation or on the unfair list. In the first judgment rendered in February, 1954, Republic was awarded $46,455.04 by the courts. However, on appeal, the suit against Decca was finally dismissed in 1956 by the United States 6th Circuit Court of Appeals as ultimately being without merit given the absence of proven harm during the contract dispute.

The crux of the complaint was whether or not Wood had violated her contract with Tennessee Records, even though it had been sidelined by the union. In the end, it was determined that her contract with Republic Records negated her earlier contract with Tennessee Records, and since as a member of the union she could not work for Tennessee Records from November 1951 on, no further harm could have been to the company while they were in violation or on the unfair list. In the first judgment rendered in February, 1954, Republic was awarded $46,455.04 by the courts. However, on appeal, the suit against Decca was finally dismissed in 1956 by the United States 6th Circuit Court of Appeals as ultimately being without merit given the absence of proven harm during the contract dispute.Her early success with Down Yonder had been turned into appearances on the Grand Ole Opry, a combination show and music promotion organization launched in 1925, and on the radio almost from the start. Her first appearance was on November 13, 1952, and subsequent appearances led to an eventual full-time gig with the show starting in late 1953, thus fulfilling her long-time dream. She considered 13 to be her lucky number from that time on. Starting in 1954, RCA Victor, under the supervision of the highly skilled young guitarist and music supervisor Chet Atkins, built a new state of the art studio in Nashville, noting the number of recording and radio stars that were emerging from that city, and wanting to capitalize on it. They grabbed a great deal of talent as soon as they could, and there was plenty of it close by. Chet, in turn, worked as a liaison with, and sometimes producer for some of his Nashville friends, and it is likely that he was the one who helped secure Del Wood a recording contract with the new guys in town. So her fame of the past few years finally culminated with a contract from RCA Victor around 1955, where she would make some of the first country/honky-tonk stereo recordings in the late 1950s.

While nothing else that Del recorded enjoyed the same success as the original Down Yonder had, including a higher quality re-recording of the piece in the RCA studio, her offerings over the next decade were frequent and consistent. It may be that the simple ensemble feel of the 1951 and 1952 tracks felt more genuine or organic than the slick studio versions turned out by RCA with the high end recorders, compression and echo they applied. Her albums still sold fairly consistently over the next several years, usually to glowing reviews all around the country, and they helped Del to gain the title "Queen of the Ragtime Pianists", sometimes shared in the 1960s with junior fellow plunker Jo Ann Castle.

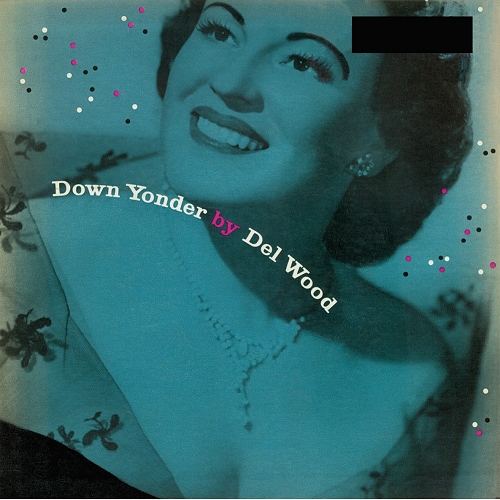

RCA was also very careful about copying the format of the descriptive liner notes, readable by browsers in the record stores, that had been working so well for Capitol Records and their line of honky-tonk piano albums, most by Lou Busch. To that end, they went with nickel-plated Colt revolvers blazing on her first album for them in 1955, named after her most famous hit, Down Yonder:

If, when we think of honky-tonk or barroom piano, we envision its exponent as a man, it is only to be expected - for almost since the days of the Gold Rush, of nickel beer and wild saloons, this has been a special property of the hard-drinking, cigar-chewing male. Since the days when pianos were laboriously packed on mule trains into mining towns and lumber camps, he has sat happily ensconced at his instrument - derby askew, sleeve garters in prominent display - pounding out his strangely tinkling, harmonically unique creations, and hoping against hope that some few kind souls will leave their drinks long enough to feed the kitty. Man it has always been, and man it will always continue to be - but, of course, there is invariably someone who will appear to break any tradition. And, although she neither smokes Havanas, wears galluses [suspenders] or tight bow ties, Del Wood is by any standards a masterful member of that ragtime coterie, a modern counterpart of all those merry musicians who made the nineties gay and the twenties roaring. In anybody's league, she plays a mean piano...

If there is any one adjective which fits Del Wood's piano stylings it is undoubtedly "refreshing." Whether it be in such old-time favorites as Twelfth Street Rag (which is obviously, as Del admits, her favorite), The Darktown Strutters' Ball, Ida!, and the redoubtable Down Yonder; in such off-beat selections as Home Sweet Home, Aloha Oe and That Naughty Waltz; or in such engaging novelties as Tie Me to Your Apron Strings Again, Ivory Corn and Smoky Mountain Polka, Del's attack is both bumptious and vastly entertaining, And, although we are listening in the comfort of our own homes, we could swear that what we hear is emanating from some dark mahogany bar and that, instead of drinking the pre-bedtime milk, we are blowing the foam from a schooner of suds.

BILL ZEITUNG - Radio Corporation of America, ©1955

In addition to her recording work and the Grand Ole Opry, Del was a regular member of the Prince Albert network show, which originated from Station WSM, and was also featured soloist, often with Little Jimmie Dickens, on both radio and its newer threatening cousin, television. The Grand Ole Opry would soon follow suit on a local, than nationally syndicated basis. The Opry and RCA also insisted on tours, so she started traveling America from coast to coast, convincing them that ragtime was back to stay, country music was not all that hokey, and to please buy her albums. There were reportedly attempts made by the Bubis brothers to either win her back or entertain the idea of another breach of contract lawsuit, but they were spending enough time already on the one against Decca, so ultimately lost out on both counts.

Del ultimately cut six albums with RCA Victor, at least a couple of them produced and even played on by Atkins. There also several singles released of tracks that did not appear on the albums. This period from 1956 to 1959, consisting of stress from the lawsuits, increased exposure to the public, more touring, and more recording, took a toll on her relationship with her husband. Del was finally divorced from Carson Hazlewood in the late 1950s. During this time she found a kindred spirit at the Opry in the form of singer Patsy Cline. As Wood stated in a later interview, one of the reasons they became close friends was because "we were sharing [domestic] problems of a similar nature."

more touring, and more recording, took a toll on her relationship with her husband. Del was finally divorced from Carson Hazlewood in the late 1950s. During this time she found a kindred spirit at the Opry in the form of singer Patsy Cline. As Wood stated in a later interview, one of the reasons they became close friends was because "we were sharing [domestic] problems of a similar nature."

more touring, and more recording, took a toll on her relationship with her husband. Del was finally divorced from Carson Hazlewood in the late 1950s. During this time she found a kindred spirit at the Opry in the form of singer Patsy Cline. As Wood stated in a later interview, one of the reasons they became close friends was because "we were sharing [domestic] problems of a similar nature."

more touring, and more recording, took a toll on her relationship with her husband. Del was finally divorced from Carson Hazlewood in the late 1950s. During this time she found a kindred spirit at the Opry in the form of singer Patsy Cline. As Wood stated in a later interview, one of the reasons they became close friends was because "we were sharing [domestic] problems of a similar nature."With changing musical tastes entering the 1960s, it was hard for Del to find a center on which to continue to sell her honky-tonk style. Country music was already heading more in the pop-music direction, and the honky-tonk craze had all but played itself out except on a couple of TV variety shows, such as Lawrence Welk where Jo Ann Castle resided. Her work at the Opry was her mainstay in the early to mid 1960s, but she did cut some albums and singles with Mercury Records during this period. Most of the content was pop songs and familiar standards played in her inimitable honky-tonk style, but little of authentic ragtime. There were even some rehashes of earlier material, including another redo of Down Yonder, albeit with unexplainable sporadic vocals interspersed throughout the performance of this and other tracks. One album from Columbia Records was released, but nothing much came of that. Even RCA Victor's repurposing of some of her 1950s material had tepid sales. Looking for new direction in her life, she adopted a son around 1967 named Wesley and raised him on her own.

During the Vietnam War, Del became part of one of the Grand Ole Opry package tours that entertained troops overseas in 1968. Her recordings after the late 1960s were infrequent at best, but she did continue to tour when she could. Wood was also the first woman president to serve a term in the Nashville Musicians Union Local 257. She was also present at the grand opening of the new $43 million entertainment complex that the Opry opened in 1974, as it had outgrown the much smaller 1891 auditorium in downtown Nashville. In later years she joined many Opry veterans in expressing displeasure at the direction it had been taking during the 1970s, often minimizing exposure of the older stars in favor of new and often untested talent. This was inevitable given the shift from radio to television, and the surge of popularity of "new country" in the 1980s. Still, she signed a new long term contract with the Atlas Artist Bureau in late July 1978.

Controversy found Wood and the Opry in 1979, when the organization was all but accused of racism in one instance, trying to find a balance between alienating long time fans and appearing progressive. Soul singer James Brown was booked for the show on Saturday, March 4. He was invited by regular cast member Porter Waggoner, but many of the other performers called Brown's appearance "a slap in the face," owing to the nature of his music style. "What's he going to sing? Papa's Got a Brand New Bag?" asked singer Justin Tubb. Del was called on as a diplomat for the sake of the press. She denied the protests had anything to do with James Brown being black. "It's not an anti-black issue. We're proud of black country entertainers like DeFord Bailey, O.B. McClinton and Charley Pride. But I'm against James Brown's music on the stage of the Opry because I love the Opry and what it stands for." The house manager, Jerry Strobel, had to counter by pointing out that other non-country music artists had performed on the broadcast over the years, including Paul McCartney, Carol Channing, Ann Margaret, Perry Como, and even former President Richard Nixon who played with a yo-yo on stage. In the end, Brown did a fine job and the protest evaporated.

In 1984 Miss Polly Hendricks was once again given an opportunity to shine in her element, and also to be memorialized on film. She played five songs in the theatrical release Rhinestone in which a an aspiring country singer from Tennessee, played by her friend Dolly Parton, comes to New York to find success, and ends up teaching country singing to a cab driver played by Sylvester Stallone. In an interview concerning the film in the Daily Reporter of February 3, 1984, Wood sounded off on a number of items:

After 30 years as a ragtime-style pianist for the Grand Ole Opry, Del Wood still needs to practice... "I'd never go on the Opry without first doing a run-through," the 63-year-old performer says. "If I live to be a 100 [sic], I'm going to do the best I can."

Even after 58 years at the keyboard, she says she enjoys playing as much as ever - despite literally thousands of rendition of her famous tune, "Down Yonder."

"I love it. It's been my heartbeat - second only to my son and family," she said. "I want to play what the public wants to hear. If I don't do 'Down Yonder' on stage, someone wants to hear it backstage. It's still my most requested number." The song, she says, "has a bounce to it, get-up-and-go, that down-home Southern flavor that's attractive to the ear."

Wood has recorded 26 albums and 60 singles and is on the road an average of one to two weeks a month. She has appeared throughout Europe and the Far East, and only Minnie Pearl with 44 years on the Grand Ole Opry has logged more time on the famous country music show.

"My music has opened doors socially and financially that I couldn't have opened with a court order," said Wood, a payroll clerk for the public health department before her entertainment career...

"I've never had any desire to sing," she said. "I do all I want to do with my 10 fingers." ...

[On Rhinestone] "It's one of the greatest thrills of my life," she said. "At my age, it's something I never expected..."

"He's a genius," Wood said of Stallone. "I had no idea he could sing country music."

Del's appearances on the Grand Ole Opry continued literally until just before her death at 69 from a stroke on October 3, 1989. She was warmly and widely remembered on her death, and in the 21st century remains an integral part of the Opry's prestigious musical history. Wood felt that more so than her many recordings, the best legacy she left behind was Wesley, who she managed to raise mostly on her own. Her fans might find both facets to be of great importance to her legacy. Ms. Wood was interred in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Nashville.

Wood was important in that she not only exemplified many of the possible connotations of the honky-tonk label, mixing country with pop music in an old-time piano style, but for the audiences she brought to both forms of music through her crossover pieces. She also made it clear that a woman's place was... well... wherever she wanted to be, making a good living in a male-dominated genre. Her forceful playing was equal or superior to many of her contemporaries, and her considerable output and original compositions showed great innovation at times, and consistency at the very least at all times.