The debate on who "invented," or more properly, who introduced ragtime to the world, or coined the name for the genre, has gone on almost since the music was first heard on stage in New York in 1895 or 1896. Music critics of that time to historians of our own time have also weighed in with varying opinions. However, there are two names that frequently come up in this regard, those of Ben Harney and Ernest Hogan. Both have legitimate claims of a sort as to introducing rag-time music in varying degrees to the stage, usually in song rather than as instrumentals, and both actually come from similar backgrounds, even though Harney was white and Hogan was black. This essay will not fully answer the question, but it will point out the possibility that Hogan may have had a slight edge in several facets of the music. His was also, as will be discovered, what one might call a "rag-time life," fraught with barriers, hilarity, drama, brushes with the law, and a somewhat tragic end.

Early Years

Hogan was born as Reuben Ernest Crowdus in Kentucky on April 17, 1865. While Ernest Reuben has been suggested as his name, it was never shown as such in any official records, so Ernest will be accepted here as his middle name. Crowden and Crowdis have also been seen as a last name, but Crowdus was the most consistently used spelling, and the name of the family that "owned" his father as a slave. The year of birth has also been cited as anywhere from 1860 to 1867. The 1870 and 1880 censuses both clearly show him to have been born in 1865. There are other reasons to warrant off a birth any earlier than that. His father, also Reuben Crowdus, had been a slave on the plantation/estate of William H. and John Crowdus in Franklin, Kentucky. In 1861 he went to war for the Confederacy in the American Civil War as a valet to Ben Hale. However, when Hale's company was captured by Union forces in 1863, Crowdus was granted his freedom and joined the 115 U.S. Colored Infantry, Company I. As such, he was considered a war veteran until his death in 1898, and received a pension later in life, which continued to support his wife until her death in the early 1900s.

It is unclear when Reuben Crowdus married Louise Hale, another former slave who was also from Kentucky, but their oldest son was born within days of the end of the Civil War and the tragic assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

The younger Reuben was followed by Pearl "Perlie" in 1868, Squire in late 1869, Blanch in 1872 and William in late 1879. Louise gave birth to five other children who did not survive infancy. The 1870 and 1880 censuses taken in the siblings' birthplace of Bowling Green, Kentucky, showed the elder Reuben working as a brick maker. They lived in a mixed-race neighborhood of laborers, and were listed as black in both records. (There were some questions of Hogan's actual race asked even during his lifetime, so this confirms his African-American heritage.)

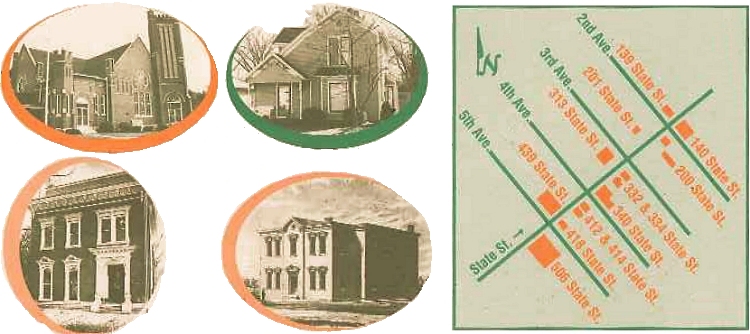

|

One of the interesting facets of Reuben's upbringing, and therefore links to the music, was that he was raised in an area of Bowling Green known as the "Shake Rag" district. Established in 1802 along the northeast end of State Street, the Shake Rag neighborhood, centered around a parcel of land donated to the city in 1802 known as Lee Square, began to expand just after the Civil War. By the early 20th century it was one of the more colored-friendly areas of the country, much less Kentucky, and African-Americans prospered there in numbers, building elaborate homes and successful businesses. But that was not the case at the time of the origins of its name, which is believed to have come from the large quantity of laundry hung on lines in the neighborhood each Monday. As some observers considered those well-worn clothes to be little more than rags, it was the shaking of these when they were removed from the line that allegedly gave the Shake Rag district its unique name. While the etymology of the origin of the word rag-time has evolved to some point of certainty even since the 1990s, and has shown any relationship between cloth rags and the music to be unlikely, this name from his home town still likely put the term "rag" in Reuben's mind, and stuck with him throughout his musical journey.

Ernest, as he preferred to be called, was, by a number of accounts, self-educated, but there may have been some combination of public and family education involved as well. He did not receive formal music education, but had a natural musical acuity. The 1880 census showed that the family was still living in Bowling Green. There were mentions in early biographies of a move to Kansas City in the 1880s, but this may be a misinterpretation from his travels. His first exposure to show business was probably as a pre-teen where he was engaged to play roles in Uncle Tom companies, based in part or as a whole on the infamous Harriet Beecher Stowe play, Uncle Tom's Cabin. He also worked as a singing and dancing pickaninny (a stereotyped version of a Negro child) in some of the increasing number of post-antebellum minstrel shows. One of the most prominent was Pringle's Georgia Minstrels. This experience gave Ernest some familiarity with black minstrelsy and the musical forms that went along with it, many of them the direct ancestors of what would become rag-time. Along the way he picked up the banjo and learned how to play it passably.

Around 1885, based on accounts of Ernest as being 20, he did make it to Kansas City with a traveling company where he met and teamed with an actor named Hogan (full identity unknown, so it may have been a stage name). They struck out on their own and formed an act known as the Hogan brothers, trading on the popular notion of Irish-named teams and themes of that period, even though they were clearly not Irish.

Singing, dancing, and dispensing comedy, they had some minor success on the Midwest circuit in 1885 into 1886. Advertisements in Saint Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, newspapers from a November, 1885, series of shows billed them as an "All-Star Combination." A year later they appeared in Washington, DC, touted as "the far-famed Kickapoo dancers," probably a reference to the Kansas Native-American tribe of the same name, and therefore perhaps another clue to the identity of the other Hogan. Ernest would keep Hogan as his stage name throughout his career, but never hide his true identity, which was often cited in newspaper stories about him.

|

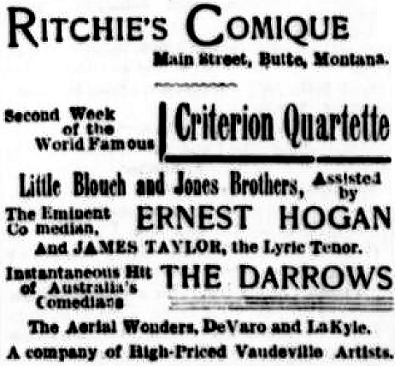

Striking out on his own, Ernest went to San Francisco, California, in 1887, and worked with western minstrel and Negro vaudeville shows for the next few years. An April, 1889, mention in the St. Paul [Minnesota] Daily Globe showed him traveling with Eaton and Parrell's Original Georgia Minstrels, appearing at the Dime Museum. By this time, Ernest had the revered position of final act (second-to-last was also a place of honor), appearing as "Uncle Reuben at Home" with Ernest billed as "the great old-man dialect comedian." The most common billing for Hogan in the early 1890s was either as "The Eccentric Comedian" or "The Eminent Comedian" when appearing at theaters around the western part of the country, including long runs in Minnesota and Montana in 1890 and 1891. In 1890, temporarily based in Chicago, Illinois, Hogan teamed up with partner Henry Eden to form Eden & Hogan's Minstrels, which toured for one season, after which he returned to the west coast.

Back in California, Ernest secured a regular position in shows held at the Bell Union Theater in San Francisco. While there, he wrote one of his first produced plays, In Old Tennessee, in which he played the principal role of an old Negro. It was unusual in that it featured a largely white cast along with a black chorus. On a brief tour the piece was generally well-reviewed.

While in San Francisco, Hogan did not always get newspaper notices in large type, but he was noted for his regular participation in cake-walk events. Cake-walks had been a Negro tradition that went back at least to the 1860s, and were reported on in newspapers as early as 1870. Sheet music depictions of the cake-walk, albeit containing music not as characteristic of the form, appeared in the mid-1870s. It was a social event that was literally what it was named for. The participant couples would dress in their very finest, then walk around the center of the venue in their best show-off gait. Those who walked with the most flair or best outfits would win a cake, sometimes with a golden ring baked into it. There were smaller cakes in successive sizes for second and third places and more.

Early articles describing this event noted that there were musicians present to play for the walk. However, in many cases, dancing, considered by some church-goers as a potentially sinful activity if unregulated, was not allowed. Even early Edison and Mutoscope films of the late 1890s clearly show the practice as a walking or even prancing exercise, but not as a dance. A close cousin to the Cake Walk might be the Virginia Reel, a somewhat more lively activity. One of the many cake-walk events at which Hogan presided was described in the San Francisco [California] Morning Call of March 26, 1892, which reported on the first evening of a two-night event:

|

The shouts and laughter of some 8000 people sealed the success of the much-heralded "cake-walk" at the Mechanic's Pavilion last night. Just exactly what a "cake-walk" is may be best gathered from the accompanying description. Anyway it is an exhibition especially favored by certain circles in colored society, although certain other circles refuse to acknowledge any but the faintest passing interest in it... A cake is the nominal prize in the "walk." Upright judges are appointed, and "style, grace and execution" form the three points for their consideration...

"Down in the Cotton-fields," was the way the programme read, and the sheet further stated that the entertainment would begin with a plantation festival arranged by Mr. Ernest Hogan, who was later introduced by Senator [Harry] Hamlin as the Ward McAllister of Chicago. At 9 o'clock the cotton-pickers arrived from the fields led by Mr. Hogan disguised as Uncle Eph. They came marching in, 40 couples, singing a plantation melody and carrying baskets of cotton. There were colored folks of all shades and sizes from six-foot Mr. Jackson down to Little Rastus, clad in the vivid blue, green, red and yellow fabrics to popular in the sunny south...

"Ladies and Gemmen," [Hogan] said, with much earnestness, "please keep quiet when de couples is walkin' in pair, 'cos dey might lose de step if youse holler at dem. So please keep quiet." This speech was applauded loud and long, and Mr. Hogan had to signal the band to go ahead to drown the noise.

Sixteen couples in evening dress came marching out. Mr. Hogan and his lady leading, Senator [Hamlin] and his partner brought up the rear. The floor was laid out with chalk, like a tennis court, and along these lines the graceful walkers glided. They made one turn of the course and the sat down for the instructions... They walked in couples up the center, and separated with an elegant bow, the gentlemen going on one side and the ladies the other. Meeting at the end, they marched up the center, only to separate at right angles to meet once more. The form of each couple and single contestant was closely criticized in this preliminary canter.

Then Mr. Hogan, the director, announced that going outside the chalk-lines was not a "foul," and proceeded to send out his flock by fours... This process is to be repeated until only the best are left, and then the final walk for the prizes comes off to-night.

Unfortunately for Hogan, in one of the first reports of many concerning his altercations with the law, he was not able to make it to the cake-walk finale, having been arrested for battery for slapping a man after the previous evening's events as a prelude to a duel. While in custody, a warrant was served on him for having hit a young lady with a cane a few weeks prior. He served a short sentence before he was back on stage in San Francisco. The following year he would be out on the road again, billed as "Ernest Hogan and the Two Little Hogans, Par Excellence of Negro Artists." [The identities of the "Two Little Hogans" were not readily located.] However, Ernest clearly aspired for more than just entertaining at local social events and small town theaters and cabarets, so he would work toward something that he felt much more worthy of his level of talent.

The Road to Fame and Controversy

While in California in 1892, Ernest met Lillian E. Todhunter, the white daughter of a wealthy Sacramento rancher. There have been suggestions that she was an actress or singer, and even some articles suggesting that she attached herself to Hogan in order to gain access to the stage, but no confirmation was found in that regard. While miscegenation was tolerated in parts of the West and Midwest, there were many areas of the country where their relationship was looked upon with a viscerally negative attitude, and was even prohibited by local laws. So their marriage, for which the unofficial wedding was performed on a ship a few miles off the California coastline, was kept relatively private for a few years. They were eventually legally wed in Chicago in August of 1895.

While miscegenation was tolerated in parts of the West and Midwest, there were many areas of the country where their relationship was looked upon with a viscerally negative attitude, and was even prohibited by local laws. So their marriage, for which the unofficial wedding was performed on a ship a few miles off the California coastline, was kept relatively private for a few years. They were eventually legally wed in Chicago in August of 1895.

While miscegenation was tolerated in parts of the West and Midwest, there were many areas of the country where their relationship was looked upon with a viscerally negative attitude, and was even prohibited by local laws. So their marriage, for which the unofficial wedding was performed on a ship a few miles off the California coastline, was kept relatively private for a few years. They were eventually legally wed in Chicago in August of 1895.

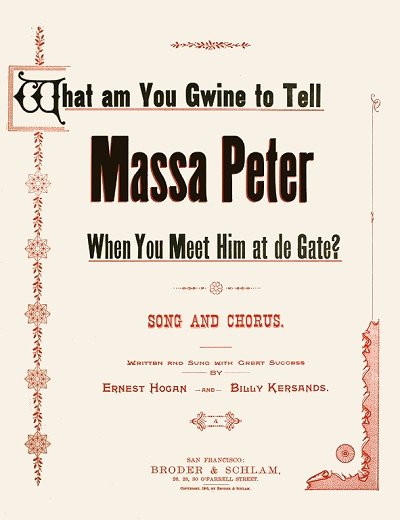

While miscegenation was tolerated in parts of the West and Midwest, there were many areas of the country where their relationship was looked upon with a viscerally negative attitude, and was even prohibited by local laws. So their marriage, for which the unofficial wedding was performed on a ship a few miles off the California coastline, was kept relatively private for a few years. They were eventually legally wed in Chicago in August of 1895.In 1893 Hogan would make his first entry into the world of music composition. With fellow musician and comedian Billy Kersands he penned the pseudo-spiritual What am You Gwine to Tell Massa Peter When You Meet Him at de Gate?, a semi-serious song with a message of repentance for his race. Interestingly enough, while this song was clearly written in what was becoming popular in entertainment as a derived but not fully disingenuous Negro or colored dialect, his next work was not. In 1894, Sweet Little Kate McCoy was published in San Francisco and featured in the July 8, 1894, Sunday Supplement of the San Francisco Call. A solo effort, this piece was, in keeping with his adopted last name, a waltz ballad of Irish persuasion written completely in a genteel English dialect with no real ethnic trace. This would be in great contrast to his next couple of works, one of which would not only define Hogan in the public eye, but haunt him for the remaining thirteen years of his life.

One of the locations that Hogan had appeared in often since his formative years as a minstrel performer was in Kansas City, Missouri, and likely on the Kansas side as well. Either Hogan already had contacts there, or was simply in town when he submitted his next work, La Pas Ma La, to publisher J.R. Bell in 1895. It had a combination of unique factors that would become more popular over the next few years. Using a Negro dialect that more or less called out dance instructions for the dance after which the piece was named, Hogan wrote a melody that had several syncopations in it. The dance itself was a comic step that Ernest had created as the Pasmala while still with the Pringle Minstrel troupe. While the lyrics do not mention the word rag, and therefore rag-time, they do evoke the feeling of the genre which was on the cusp of bursting forth upon the public. Composer Scott Joplin, in his Ragtime Dance ballet of 1902, would use a similar device in his lyrics, and the general melodic meter and cadence would also surface years later in the enduring 1913 hit Ballin' the Jack by black composers Chris Smith and Jim Burris. The rhythm was suggested by the dance step, which was comprised of a jerky hop forward followed by three quick backward steps. While it never found the same favor as the cake-walk, the pasmala was a mildly popular dance within elements of the black community. Another device within the piece that would be found in a number of ragtime tunes a decade later, although not as authentic to the feel of the music, was a largely habanera left hand. The tune was soon released as an instrumental as well, giving it a tenuous claim as the first published instrumental work in the rag-time style.

Another device within the piece that would be found in a number of ragtime tunes a decade later, although not as authentic to the feel of the music, was a largely habanera left hand. The tune was soon released as an instrumental as well, giving it a tenuous claim as the first published instrumental work in the rag-time style.

Another device within the piece that would be found in a number of ragtime tunes a decade later, although not as authentic to the feel of the music, was a largely habanera left hand. The tune was soon released as an instrumental as well, giving it a tenuous claim as the first published instrumental work in the rag-time style.

Another device within the piece that would be found in a number of ragtime tunes a decade later, although not as authentic to the feel of the music, was a largely habanera left hand. The tune was soon released as an instrumental as well, giving it a tenuous claim as the first published instrumental work in the rag-time style.In essence, many historians believe this to be arguably one of the earliest examples of ragtime music. That argument can be tempered by the habanera and other subtle factors. It does bring up another topic, however. Having presided over so many cake-walk events over the prior decade, it is likely that Hogan's exposure to some of the styles of music played at those events helped to form his conception of cakewalk [minus the hyphen to delineate the music from the event] rhythms. There was no one composer or musician who introduced the musical cakewalk into the world, as it was likely more of a co-evolved effort. However, Hogan's fame and importance as a stage presence certainly helped to get this direct predecessor into print.

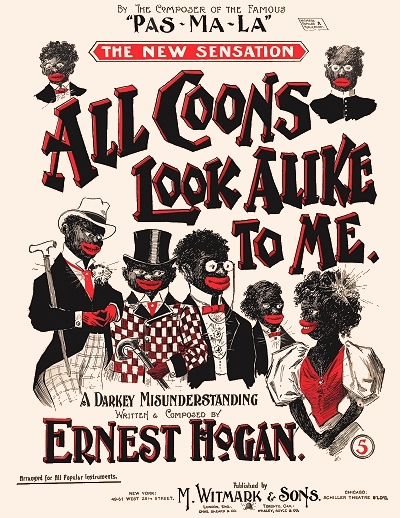

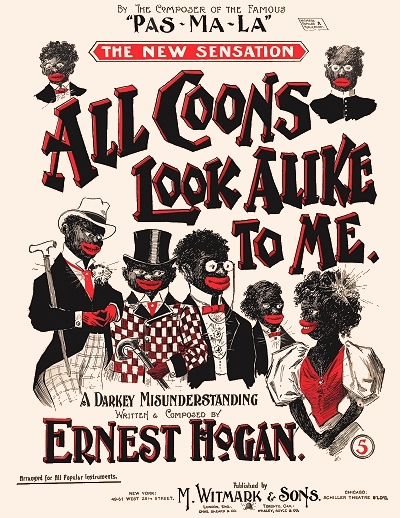

Reuben Crowder's next move was to the place that was the pinnacle of performance locations, New York City. It was there that his next song appeared. The premise of the narrative was suggested by a song he had heard in a Chicago bar, which was a dialog between a "dusky dame" and her "dark suitor," in which she dismissed him for another, saying "All pimps look alike to me." Surprisingly, even in a historical perspective, when Ernest worked to create a similar song for himself, he felt that the derogatory term "coon" would be less offensive than the rather harsh "pimp." There were a number of other terms he could have used, of course. But he ended up with the mildly musical and comical All Coons Look Alike to Me. It was shopped around a bit, then taken to the firm of M. Witmark. It has been suggested that Witmark himself reshaped the verse into something more passable that would better support the chorus. More important was the "Choice Chorus" appended to the end which included a "Negro Rag" accompaniment scored by Max Hoffmann, perhaps the first genuine scored ragtime in print. Then Witmark's professional managers, whose job it was to shop songs around to various performers, managed to get it placed into one of the top shows of 1896, The Widow Jones, starring the bigger than life (and physically larger than many of her co-stars) May Irwin.

The result was an instant hit from day one, one which would allegedly eclipse a million copies in sales [hard to verify this statement]. It was also recorded to a cylinder before the year was out by white singer Len Spencer, followed in short order by another one with Vess Ossman at the banjo. While this all translated into a positive success, the negative ripple effect was much worse. The word "coon" as associated with African-Americans dated back to the 1830s, and was indeed used in the title of a very popular piece of 1834, The Zip Coon, later known as Turkey in the Straw. Coon was reportedly a play on "raccoon," given that creature's propensity for stealing food amongst other things. The term "coon song" had been used in the 1880s as well, but not all that universally. Many such songs had even been written by black composers, and performed by them on stage while they were ironically wearing black-face makeup. In fact, Ernest had done the same thing. But May Irwin managed to make All Coons Look Alike to Me a notorious hit that helped to make her one of the original "coon shouters," a trend of white performers singing songs in Negro dialects, which spread across the United States over the next year. Hogan's piece has historically been considered by many to be the first major "coon song" that spawned hundreds of others, some of them even moderate hits. It also gave the white population, at least those who dared, a new universal racial slur, and a way to make fun of or even antagonize people of color, simply by humming or whistling the tune. Many black performers who had respect for the popularity of the piece nonetheless sometimes substituted that one word for anything else that made sense and was less derogatory. Given the trend that it ignited, and the way it was used to incite or deride others as well, this one song, which earned as much as $26,000 for Ernest over the next thirteen years, was also his one major regret, as he admitted in an interview before his death:

But May Irwin managed to make All Coons Look Alike to Me a notorious hit that helped to make her one of the original "coon shouters," a trend of white performers singing songs in Negro dialects, which spread across the United States over the next year. Hogan's piece has historically been considered by many to be the first major "coon song" that spawned hundreds of others, some of them even moderate hits. It also gave the white population, at least those who dared, a new universal racial slur, and a way to make fun of or even antagonize people of color, simply by humming or whistling the tune. Many black performers who had respect for the popularity of the piece nonetheless sometimes substituted that one word for anything else that made sense and was less derogatory. Given the trend that it ignited, and the way it was used to incite or deride others as well, this one song, which earned as much as $26,000 for Ernest over the next thirteen years, was also his one major regret, as he admitted in an interview before his death:

But May Irwin managed to make All Coons Look Alike to Me a notorious hit that helped to make her one of the original "coon shouters," a trend of white performers singing songs in Negro dialects, which spread across the United States over the next year. Hogan's piece has historically been considered by many to be the first major "coon song" that spawned hundreds of others, some of them even moderate hits. It also gave the white population, at least those who dared, a new universal racial slur, and a way to make fun of or even antagonize people of color, simply by humming or whistling the tune. Many black performers who had respect for the popularity of the piece nonetheless sometimes substituted that one word for anything else that made sense and was less derogatory. Given the trend that it ignited, and the way it was used to incite or deride others as well, this one song, which earned as much as $26,000 for Ernest over the next thirteen years, was also his one major regret, as he admitted in an interview before his death:

But May Irwin managed to make All Coons Look Alike to Me a notorious hit that helped to make her one of the original "coon shouters," a trend of white performers singing songs in Negro dialects, which spread across the United States over the next year. Hogan's piece has historically been considered by many to be the first major "coon song" that spawned hundreds of others, some of them even moderate hits. It also gave the white population, at least those who dared, a new universal racial slur, and a way to make fun of or even antagonize people of color, simply by humming or whistling the tune. Many black performers who had respect for the popularity of the piece nonetheless sometimes substituted that one word for anything else that made sense and was less derogatory. Given the trend that it ignited, and the way it was used to incite or deride others as well, this one song, which earned as much as $26,000 for Ernest over the next thirteen years, was also his one major regret, as he admitted in an interview before his death: [All Coons Look Alike to Me] caused a lot of trouble in and out of show business, but it was also good for show business because at the time money was short in all walks of life. With the publication of that song, a new musical rhythm was given to the people. Its popularity grew and it sold like wildfire... That one song opened the way for a lot of colored and white songwriters. Finding the rhythm so great, they stuck to it ... and now you get hit songs without the word 'coon.' Ragtime was the rhythm played in backrooms and cafes and such places. The ragtime players were the boys who played just by ear their own creations of music which would have been lost to the world if I had not put it on paper.

While any claim to All Coons being the first published ragtime tune are nebulous and suspect at best, it was the first popular tune of the genre, and within a year would be touted that way. There were other contenders in the field holding forth in 1896, including the aforementioned Ben Harney from Kentucky, and his New York-born protégé Mike Bernard. May Irwin's role in popularizing the music momentarily put aside, Harney and Bernard could be considered as the first white performers, or more specifically, pianists, of the new hyphenated rag-time genre. Harney was the first to reportedly use the word in public. It should further be noted that San Francisco by way of Chicago composer Theodore H. Northrup, with whom Hogan would pen some pieces, arguably had the first published piece in print that linked the pasmala with ragtime, his own Louisiana Rag. But it was Ernest Hogan who was the first Negro performer and writer of the genre that received credit and acclaim for his work.

|

As for naming "rag-time": Music critics from as early as 1898 strained their own credulity in trying to suggest some etymology for the word rag-time, but most failed. The common conception was that the melodic rhythms were torn up into bits like rags, as in ragged-time, or that the form originated from poor black musicians who wore them. Even the originators themselves seemed hard-pressed to come up with an explanation. Note that the earlier reference to Hogan growing up in the "shake rag" district of Bowling Green, while a nice association to make, had no role in naming the music, and to that end, Harney may have actually been the first to publicly coin the word, which was probably already being thrown about casually by 1896. It is a combination of references, most of them associated with either a type of dance, or more likely a dance event, called a "rag." Such rag events were known of even in the early 1880s, and even noted ragtime publisher John S. Stark wrote an article published in Saint Louis in November, 1901, that further tied the music to such events. There were also a number of mentions in Midwest newspapers from the mid-1890s about parties referred to as rent rags, essentially a home concert for which an admission was charged in order to raise rent money. But by 1900, the origin mattered less than the currency of the music, for, as one period song said, Everything in America is Ragtime. Harney, Bernard, and Hogan were among the earliest beneficiaries of this trend.

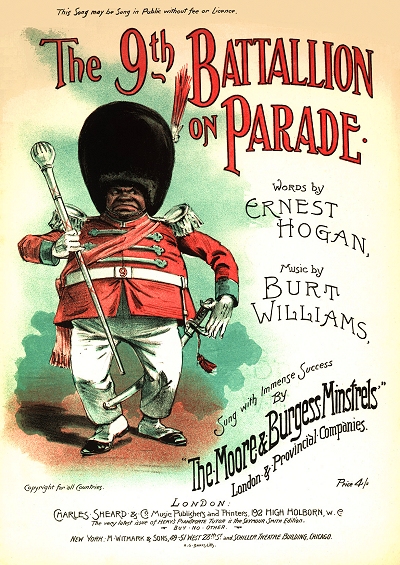

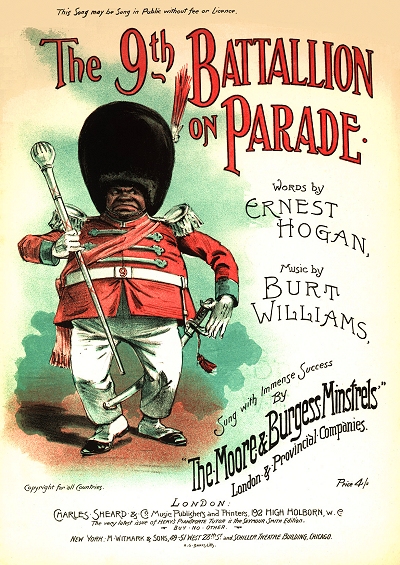

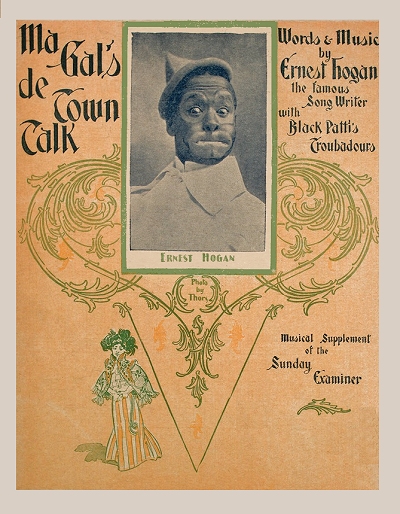

Now considered a valuable commodity for his comedy and musical ability, Hogan was recruited into a black vaudeville troupe known as the Georgia Graduates, with which he toured during the last part of 1896 well into 1897. Then he went another step up the ladder, integrated into the more famous company known as the Black Patti Troubadours. It was founded by singer Matilda Sissieretta Jones, an African-American soprano who sang operatic numbers after the style of her European namesake, Italian singer Adelina Patti. Also in the troupe were black composers Bob Cole and Billy Johnson, as well as comedians Bert Williams, with whom he wrote The 9th Battalion Parade, and Williams' comedic partner George Walker. It was most likely during his year touring with the Black Patti company that Hogan gained his billing as "The Unbleached American," a title referring to both his pigment and nationality. During his stint with the show he was ostensibly the major male star, as well as the master of ceremonies. He also wrote and published a few more songs from 1897 into 1898, plus had some additional pieces incorporated into the Black Patti shows. Then, opportunity came knocking for Mister Crowdus, and he readily answered the call.

Stardom and Heartbreak

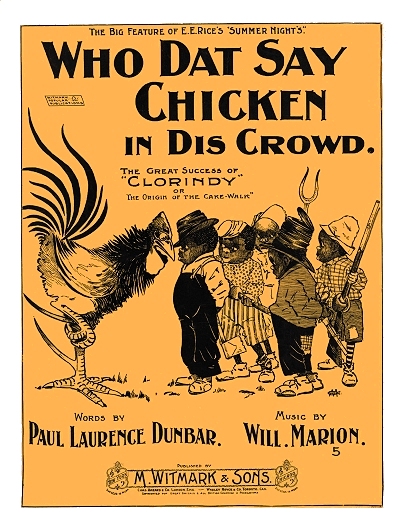

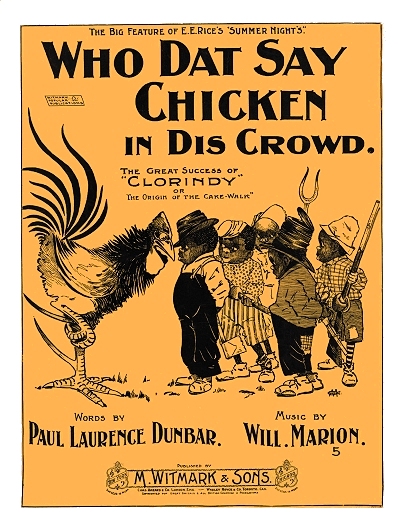

By 1898 Ernest had the name and gravitis to do what had been unthinkable even a few years earlier — become a star of the "legitimate" New York stage. Composer Will Marion Cook, an esteemed mulatto musician with a difficult and prickly demeanor, had also aspired for equality in the musical world, looking to put black theater and music on equal footing with that of the white crop of writers of stage musicals. With esteemed poet Paul Laurence Dunbar he wrote Clorindy: or the Origin of the Cake Walk. It was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing the cause of the race through a carefully crafted libretto and music. Hogan was bought in as the star of the show, and had enough pull that he applied some editing to Dunbar's libretto and lyrics. While it did not play in an indoor theater, with some sympathetic assistance from the Casino Theater Roof Garden orchestra leader, John Braham, the show opened at their roof venue on July 5, 1898.

It was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing the cause of the race through a carefully crafted libretto and music. Hogan was bought in as the star of the show, and had enough pull that he applied some editing to Dunbar's libretto and lyrics. While it did not play in an indoor theater, with some sympathetic assistance from the Casino Theater Roof Garden orchestra leader, John Braham, the show opened at their roof venue on July 5, 1898.

It was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing the cause of the race through a carefully crafted libretto and music. Hogan was bought in as the star of the show, and had enough pull that he applied some editing to Dunbar's libretto and lyrics. While it did not play in an indoor theater, with some sympathetic assistance from the Casino Theater Roof Garden orchestra leader, John Braham, the show opened at their roof venue on July 5, 1898.

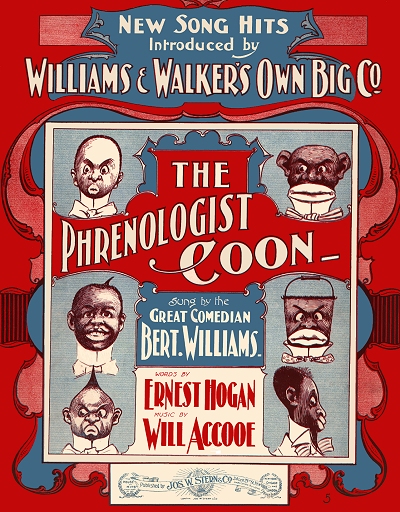

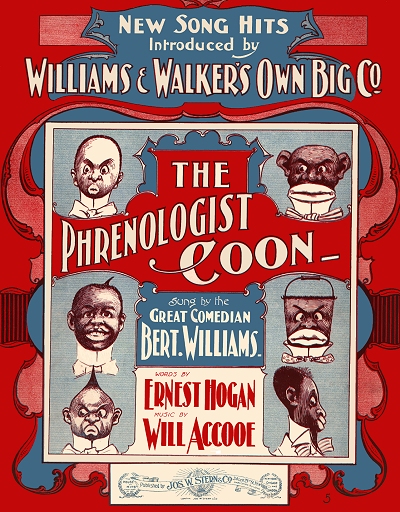

It was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing the cause of the race through a carefully crafted libretto and music. Hogan was bought in as the star of the show, and had enough pull that he applied some editing to Dunbar's libretto and lyrics. While it did not play in an indoor theater, with some sympathetic assistance from the Casino Theater Roof Garden orchestra leader, John Braham, the show opened at their roof venue on July 5, 1898.Clorindy enjoyed nearly six months of success in the press and with the public, three of them in a touring company, albeit mostly with its expected target audience, which were the blacks of New York City and surrounding areas. It received fine reviews in mainstream papers as well, so managed to hook in some curious white theater-goers and those with an interest in the music itself. In spite of the good reviews, Cook's musically educated mother was evidently nonplussed with Clorindy. She reportedly cried after hearing it, lamenting her son's evident turnabout from a high classical education on the violin composing in low popular music forms, saying to him, "I've sent you all over the word to study and become a great musician, and return such a nigger!" This both hurt and inspired him to elevate the status of Negro music by infusing it with classical music ideals and paradigms, making it more sophisticated while not denying the source material as coming from his race. As for Hogan, his performance of some of the particular pieces, including the moderate hit Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd, both increased his value as a popular stage performer, and helped to further reinforce his personal association with the coon or lazy Negro stereotype that his race was already fighting. Songs from Clorindy in addition to his own works, many with exaggerated stereotyped cover images, actually became popular with white audiences and performers who tended to lampoon the blacks, and made inflammatory labels like "coon," "darkie" and "nigger" more socially acceptable through performance, counter to the intent of some of the writers and the wishes of black leaders. The lyric content of some of the songs from that period was even more disturbing in its degrading and sometimes even violent content concerning blacks.

There was, however, a positive effect from the popularity of Hogan and Clorindy, as well as that of Irwin, Bernard and Harney. Rag-time, as it was still being spelled in the late 1890s, a music associated with the black population of the United States (although arguably more of a collective amalgamation of both black and white music forms and melodies) was gaining popularity, and its originators and proponents benefitted in many ways from what was clearly a new and uniquely American music. There were inane arguments as early as the last two years of the century as to who the single originator, of which there was none, of the music was. Competitions among pianists started to pop up, echoing those of banjo players who had been holding forth with their own playing competitions for two decades. One of the largest, which involved Mike Bernard, was held on January 23, 1900, sponsored by Richard K. Fox and his famous social tabloid, the pink-covered National Police Gazette. While Hogan was not involved with this contest, his by-now familiar All Coons song was played in varying styles by many of the contestants, as it was one of the most popular songs inherently associated with rag-time music. It is unclear if Bernard, who prevailed over the event, also played it. But what was important is that through the efforts of Hogan and his associates, America now had its own musical identity, and it was growing in popularity every week. Consider that when a musical style or genre, even one that does not have lyrics associated with many of its pieces, is so powerful that it creates endless debates in the press, and is even banned by some local musicians unions, it must have really had a significant impact on the public.

(although arguably more of a collective amalgamation of both black and white music forms and melodies) was gaining popularity, and its originators and proponents benefitted in many ways from what was clearly a new and uniquely American music. There were inane arguments as early as the last two years of the century as to who the single originator, of which there was none, of the music was. Competitions among pianists started to pop up, echoing those of banjo players who had been holding forth with their own playing competitions for two decades. One of the largest, which involved Mike Bernard, was held on January 23, 1900, sponsored by Richard K. Fox and his famous social tabloid, the pink-covered National Police Gazette. While Hogan was not involved with this contest, his by-now familiar All Coons song was played in varying styles by many of the contestants, as it was one of the most popular songs inherently associated with rag-time music. It is unclear if Bernard, who prevailed over the event, also played it. But what was important is that through the efforts of Hogan and his associates, America now had its own musical identity, and it was growing in popularity every week. Consider that when a musical style or genre, even one that does not have lyrics associated with many of its pieces, is so powerful that it creates endless debates in the press, and is even banned by some local musicians unions, it must have really had a significant impact on the public.

(although arguably more of a collective amalgamation of both black and white music forms and melodies) was gaining popularity, and its originators and proponents benefitted in many ways from what was clearly a new and uniquely American music. There were inane arguments as early as the last two years of the century as to who the single originator, of which there was none, of the music was. Competitions among pianists started to pop up, echoing those of banjo players who had been holding forth with their own playing competitions for two decades. One of the largest, which involved Mike Bernard, was held on January 23, 1900, sponsored by Richard K. Fox and his famous social tabloid, the pink-covered National Police Gazette. While Hogan was not involved with this contest, his by-now familiar All Coons song was played in varying styles by many of the contestants, as it was one of the most popular songs inherently associated with rag-time music. It is unclear if Bernard, who prevailed over the event, also played it. But what was important is that through the efforts of Hogan and his associates, America now had its own musical identity, and it was growing in popularity every week. Consider that when a musical style or genre, even one that does not have lyrics associated with many of its pieces, is so powerful that it creates endless debates in the press, and is even banned by some local musicians unions, it must have really had a significant impact on the public.

(although arguably more of a collective amalgamation of both black and white music forms and melodies) was gaining popularity, and its originators and proponents benefitted in many ways from what was clearly a new and uniquely American music. There were inane arguments as early as the last two years of the century as to who the single originator, of which there was none, of the music was. Competitions among pianists started to pop up, echoing those of banjo players who had been holding forth with their own playing competitions for two decades. One of the largest, which involved Mike Bernard, was held on January 23, 1900, sponsored by Richard K. Fox and his famous social tabloid, the pink-covered National Police Gazette. While Hogan was not involved with this contest, his by-now familiar All Coons song was played in varying styles by many of the contestants, as it was one of the most popular songs inherently associated with rag-time music. It is unclear if Bernard, who prevailed over the event, also played it. But what was important is that through the efforts of Hogan and his associates, America now had its own musical identity, and it was growing in popularity every week. Consider that when a musical style or genre, even one that does not have lyrics associated with many of its pieces, is so powerful that it creates endless debates in the press, and is even banned by some local musicians unions, it must have really had a significant impact on the public.When the Clorindy tour, integrated into a larger body known as the Senegambian Carnival in the fall, left New York for other locations, Ernest, mindful of his singular success in that town, decided to stay. He joined the company of John W. Isham's Octoroons late in the year, and continued into the spring. In May he appeared in the show Captain Kidd, staged in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and for which he was the only non-white cast member, a unique honor. Then came a real test of Hogan's fortitude and resourcefulness.

A new touring troupe known as Curtis' Afro-American Minstrels was assembled by novice theatrical entrepreneur M.B. Curtis, with the mission of taking American entertainment to an international audience. Looking for star power, Curtis sought out Hogan, and signed him to a contract, giving him top billing and the title of "Director of Amusements." Unfortunately, due to the timing, this prevented Ernest from starring in Cook's next show, Jes' Lak White Folks, which had reportedly been written with him in mind. Along with another Curtis troupe member, comic Billy McClain, Ernest concocted the one-act comedy My Friend from Georgia, which they performed as part of the Curtis group on a tour that took them to New Zealand and the continent of Australia. However, another similar troupe, O.M. McAdoo's Minstrels, had beat them to the punch by two weeks in July of 1899. The competition meant diminished audiences and slimmer box office receipts.

Curtis had neither the business acumen or experience to overcome this obstacle. This misfortune meant that he was not able to pay his actors and musicians, and reportedly even pulled a revolver on them when they became insistent. This understandably resulted in defections, including McClain, who went to work for the competition. When Curtis disappeared with the remaining funds, Hogan and fifty or so others were left stranded in Australia.

|

Ernest managed to form his own troupe of 29 out of the remnants of the Curtis company with some unique content, and from the fall of 1899 into the winter of 1900 played several dates, largely around Brisbane on the east coast, which bolstered his reputation as a viable entertainer. Reviews of Hogan's performances were generally good throughout the run, The show earned him enough to get boat fare to travel as far as the recently acquired territory of Hawai'i. Ernest had arranged for the company to be booked at the Honolulu Orpheum theater starting on March 17, with the goal of earning enough to take the company on a steamship back to the United States in early April. Reviews there were generally all good, if steeped in racist terms. One of the read: "We all have our uses 'tis said, and Hogan's predestination in life must have been to make cheery the waste places. He is the funniest coon, the most original coon, the coon with the most contagious laugh that ever ate a watermelon or craved a chicken." The entire run was quite successful. However, when they were ready to depart on April 12, it was suddenly noticed that Hogan and his troupe were Negros, and they were not allowed to board the Canadian-Australian R.M. Steamship Company vessel Miowera owing to a "lack of cabin space," an allegation later proven to be blatantly false. Even worse, they were not refunded their prepaid reservation money.

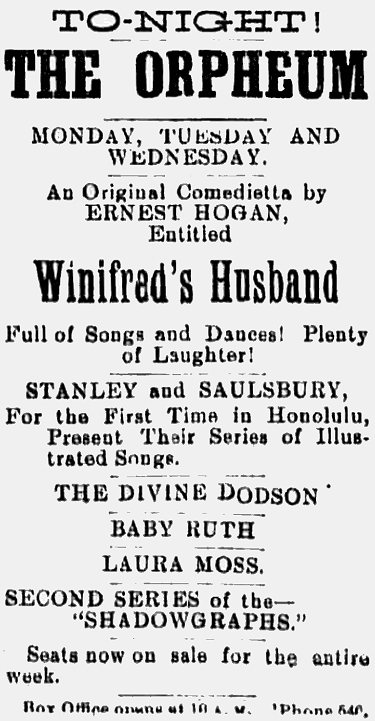

Working with legal counsel to try and get their refund through twenty nine suits filed on behalf of the company at $586,000, Hogan also figured they might as well keep busy and work during their extended stay. Over the next six weeks he wrote and produced three entirely new shows in order to keep audiences coming to the Orpheum, including A Country Coon, Winifred's Husband and a variation of 'Round the World in 80 Days, in addition to having earlier revived Uncle Tom's Cabin. Hogan's troupe became genuinely beloved stars while in Honolulu, participating in everything from local competitions to charity baseball tournaments and benefit concerts, receiving several accolades and awards from the islanders. Finally, by late May, successful negotiations were made with a shipping line that was more amenable to people of color. Having made a point in the newspaper of paying all of their accrued debts before departure, Ernest and his troupe finally got back to the United States mainland in June, nearly a year after he had left for Australia. He had most certainly earned his keep along the way, and became an even more viable commodity as a black entertainer, and now producer. As an after-the-fact but still important triumph, Hogan obtained his refund and much more in a settlement with the errant shipping company in August of that year owing to three of the twenty-six suits being settled in their favor to date.

By the time of the 1900 census taken on June 9, Ernest was supposedly back in Manhattan. This particular enumeration has at least a couple of curiosities associated with. First, it seems unlikely he was actually back from Hawai'i when the data was taken, given the departure date of the ship. Furthermore, he was listed as white, even though the remaining parameters were relatively accurate, showing him as an actor. Lillian was also in the home, and listed as a seamstress, not directly related to show business in any regard. Where this becomes interesting is that in the summer of 1897 it was reported in the press that Lillie had filed for divorce from her husband, and that he had filed his own counter-suit, similarly asking for divorce. One of the stories from late July, 1897, further noted that at that time she was in New York trying to "patch up peace with her dusky husband." Their truce evidently held for some time, but theirs was a contentious relationship, likely exacerbated by racial differences and outside pressure, as well as nearly a year apart. The couple was separated by the end of 1900 and were soon divorced.

One of the stories from late July, 1897, further noted that at that time she was in New York trying to "patch up peace with her dusky husband." Their truce evidently held for some time, but theirs was a contentious relationship, likely exacerbated by racial differences and outside pressure, as well as nearly a year apart. The couple was separated by the end of 1900 and were soon divorced.

One of the stories from late July, 1897, further noted that at that time she was in New York trying to "patch up peace with her dusky husband." Their truce evidently held for some time, but theirs was a contentious relationship, likely exacerbated by racial differences and outside pressure, as well as nearly a year apart. The couple was separated by the end of 1900 and were soon divorced.

One of the stories from late July, 1897, further noted that at that time she was in New York trying to "patch up peace with her dusky husband." Their truce evidently held for some time, but theirs was a contentious relationship, likely exacerbated by racial differences and outside pressure, as well as nearly a year apart. The couple was separated by the end of 1900 and were soon divorced.Cook had not fared well with Jes' Lak White Folks, and was unable to convince a reticent Dunbar to help him retool it. Black writer James Weldon Johnson stepped in to mediate, and eventually ended up writing the libretto and most of the lyrics that became The Cannibal King, which opened in London in mid-1899. It was brought back to New York with some success, but Cook also wanted his prior show staged, now that Hogan was back in town. Ernest was able to step into the lead role of the show almost as soon as the secured the use of the Cherry Blossom Grove Roof Garden Theater very near Times Square, and Dunbar stepped in to do some tweaking. Of his demeanor while working with the author, Johnson later described Ernest as: "expansive, jolly, radiating infectious good humor, provoking laughter merely by the changing expressions of his mobile face."

Jes' Lak White Folks was staged closer to an actual Broadway theater than any previous black-written, produced and cast show. It was just on the outdoor roof portion, rather than inside. However, the timing of its opening in the summer of 1900 became rather unfortunate for Ernest, and a sharp contrast to the treatment he had received just months before in Hawai'i. Late on August 12, after the show had been playing for a couple of months, there was a fight between a white and black man at the corner of 41st Street and Eighth Ave, not far from Times Square. While there are a couple of reports suggesting that the white man escalated the conflict by whistling the tune All Coons Look Alike to Me, inciting the rage of the black man, this may have been an effort by the press to raise the stakes of the conflict after the fact. In any case, the white man hit the black one with a club or blackjack, and the black man, one Arthur Harris, responded with a knife. It turns out that he had mortally wounded an off-duty police officer named Robert J. Thorpe. This, of course, set the white population into a rage, exacerbated when Thorpe finally died of his injuries on the 14th. August 15th was his well-publicized wake, for which a large crowd gathered outside the officer's Ninth Avenue home. The summer heat and the emotions of the day prevailed over common sense, creating conditions for a race riot starting roughly around 11 PM, which spread from the Tenderloin district on the west side over to Times Square.

It was soon after that when Hogan exited the Cherry Blossom Grove to the street, accompanied by George Walker and Clarence Logan, personal assistant to Williams and Walker who had been on the tour to Hawai'i. Hogan in particular was quickly recognized by those who had seen his picture in the newspaper or on sheet music covers, and it took only one person shouting "Get Ernest Hogan!" and "Get George Walker!" to set an angry mob into motion. Walker and Logan managed to get in a car, but it was attacked after a few blocks. Walker managed to escape, but Logan was eventually pulled from the car and beat unmercifully before he was rescued by police. As for Hogan, he literally ran for his life for several blocks, escaping into the Marlborough Hotel at 36th and Broadway. Plainclothes officer Detective Madden, who happened to be at the hotel to deal with the mob, kept them at bay with his revolver until Hogan could make a clean escape in a cab. Ultimately some fifty people were injured and several killed in the bloody four hour riot, to which over 700 policeman were dispatched. Hogan was shaken to his core, and ended his run with Jes' Lak White Folks in short order, judiciously choosing instead to go on the road in vaudeville until racial tensions cooled in Manhattan.

As for Hogan, he literally ran for his life for several blocks, escaping into the Marlborough Hotel at 36th and Broadway. Plainclothes officer Detective Madden, who happened to be at the hotel to deal with the mob, kept them at bay with his revolver until Hogan could make a clean escape in a cab. Ultimately some fifty people were injured and several killed in the bloody four hour riot, to which over 700 policeman were dispatched. Hogan was shaken to his core, and ended his run with Jes' Lak White Folks in short order, judiciously choosing instead to go on the road in vaudeville until racial tensions cooled in Manhattan.

As for Hogan, he literally ran for his life for several blocks, escaping into the Marlborough Hotel at 36th and Broadway. Plainclothes officer Detective Madden, who happened to be at the hotel to deal with the mob, kept them at bay with his revolver until Hogan could make a clean escape in a cab. Ultimately some fifty people were injured and several killed in the bloody four hour riot, to which over 700 policeman were dispatched. Hogan was shaken to his core, and ended his run with Jes' Lak White Folks in short order, judiciously choosing instead to go on the road in vaudeville until racial tensions cooled in Manhattan.

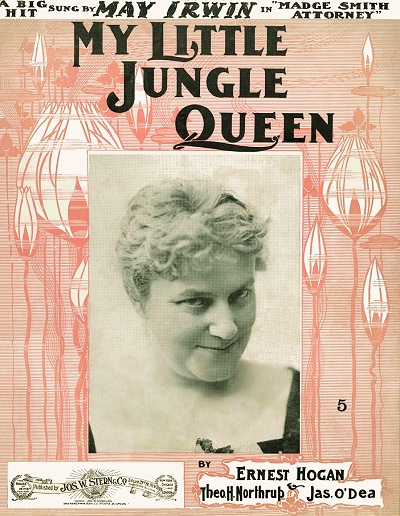

As for Hogan, he literally ran for his life for several blocks, escaping into the Marlborough Hotel at 36th and Broadway. Plainclothes officer Detective Madden, who happened to be at the hotel to deal with the mob, kept them at bay with his revolver until Hogan could make a clean escape in a cab. Ultimately some fifty people were injured and several killed in the bloody four hour riot, to which over 700 policeman were dispatched. Hogan was shaken to his core, and ended his run with Jes' Lak White Folks in short order, judiciously choosing instead to go on the road in vaudeville until racial tensions cooled in Manhattan.In December, Hogan came back to New York to contribute some songs to a May Irwin vehicle titled Madge Smith, Attorney He teamed with well-known white composers Theodore Northrup and James O'Dea for a series of character songs making up much of the material in the show. Of them, My Little Jungle Queen became a moderate hit, as did The Jack-O'Lantern Coon. Even though he could and did write a few pieces on his own, including De Congregation Will Please Keep Their Seats for his vaudeville tour, Hogan knew to depend on other established sources, working with them to get the best possible material for his act.

Taking to the road again briefly, Hogan was back in town by the early spring of 1901. He settled in to the New York Theater just off Times Square at 44th and Broadway, which was a high-class vaudeville house, ultimately playing there for forty weeks. His $300 per week salary as a headliner allowed him to purchase a three-story home on 134th Street in the heart of Harlem. Up to that point, many southern black migrants who came to New York had gone up to that area, which started more or less at 125th Street north of Central Park. Hogan, however, was the first black star of an important stature to settle there, and he would soon be followed by many others, making Harlem a black hot spot from the 1910s well into the 1930s.

That fall, Hogan, remembering how well he had been treated in Honolulu, returned to Hawai'i with his company in November. While there, he was joined once again in December by Billy McClain who had come with another show, and they teamed up as they had during their Australian run. McClain's wife Madame Cordelia as joined in with the company. As with before, Hogan received many fine accolades in the Hawaiian Star and Honolulu Republican papers. An amusing little item on him appeared in the Maui News by way of the New York Clipper on December 7, 1901, highlighting his fine sense of humor:

Not long ago [Hogan] was rehearsing his act and songs at the Orpheum, where the music is under direction of E. M. Rosner, a most capable musician in this particular branch of the business. At a certain place in one of Hogan's numbers he introduced [a] dance. This day he seemed unable to catch on to the dance part and made several false starts. Finally Rosner exclaimed:

"Well, Hogan, what's matter with your feet to day?"

"I don't know, Mr. Rosner. Something's wrong, but what it is I can't tell. Let me try it again."

The trial was made, and still Hogan's feet failed to make good with the music. After two or three more attempts he stopped short as if struck by a thought.

"By the way, Mr. Rosner," said he, "what key are you playing the music in?"

"In the key of F," was the answer.

"I knew it - I knew it, said Hogan. "There's where the difficulty is. I never could dance in any key but G."

While there, Hogan and the gang again participated in benefit appearances and other special events. After twelve very successful weeks, Hogan and company left in February of 1902 to return to the mainland. It was his last appearance in the Hawai'ian islands. Back in New York, McClain and Hogan made some appearances in various vaudeville houses in New York, and started hatch a plan for a new show to be launched in the fall. In the interim, Ernest had found love again, and decided to do something about it.

Back in New York, McClain and Hogan made some appearances in various vaudeville houses in New York, and started hatch a plan for a new show to be launched in the fall. In the interim, Ernest had found love again, and decided to do something about it.

Back in New York, McClain and Hogan made some appearances in various vaudeville houses in New York, and started hatch a plan for a new show to be launched in the fall. In the interim, Ernest had found love again, and decided to do something about it.

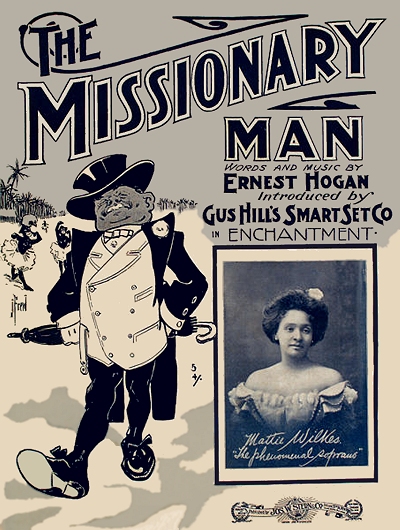

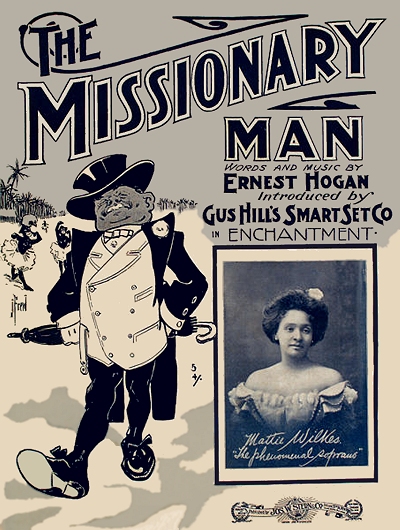

Back in New York, McClain and Hogan made some appearances in various vaudeville houses in New York, and started hatch a plan for a new show to be launched in the fall. In the interim, Ernest had found love again, and decided to do something about it.It is not clear when Hogan met the young mulatto soprano and actress Mattie V. Wilkes (b.1878). While some sources have reported that they met during a run of The Military Man, this show was not launched until 1903 after they were wed, with Hogan heading the cast, and Mattie as part of it. A more viable suggestion was that Hogan was introduced to Mattie by George Walker in 1899 during her run in The Policy Players. They would marry on May 11, 1902.

Ernest and Billy revamped My Friend from Georgia as the core of their act, an effort supported and promoted by white entrepreneur Gus Hill. Mattie would tour with her husband and Mr. and Mrs. McClain on the vaudeville circuit around the Northeast, including Providence, Boston and Syracuse. With the help of Hill, they created a new ensemble called The Smart Set, with their initial feature titled Enchantment staged starting in late September. It had a book by S.B. Casson and music by Hogan and others, arranged by James F. Dougherty. The core of the group was comprised of Hogan and McClain along with their wives. They received high praise, tumultuous applause, and largely positive reviews published in newspapers from Philadelphia to Albany and Syracuse. The hit of the show appeared to be Missionary Man by Hogan and lyricist Steve Cassin. While the quartet and their company traveled through the end of the year, according to later reports the union between Ernest and Mattie was never really a happy one, although it ultimately came down to a he-said/she-said situation.

Even though they continued to work together on stage into February of 1903, it was reportedly on August 17, 1902, when the newlyweds had their fateful fight. According to a court record, Mattie claimed that around midnight on the 17th that her husband had "without any cause or provocation, brutally, violently and cruelly assaulted me by repeatedly striking me with his clenched hand and kicking me upon the body; that he dragged me across the floor, out into the hallway and threw and kicked me down two flights of stairs; that as a result thereof I was helplessly confined to my bed for two days, suffering excruciating pain and agony; that on the said occasion the defendant divested me of my clothing, tore the same from my body and in the presence of numerous, and divers persons drove me from the house in view of many persons. In the condition aforesaid—almost entirely nude and naked." The result was that she reportedly eventually lost her voice, the one thing that had helped her to earn $50 per week on the stage.

There were a litany of additional charges in the complaint, including language and epithets that the newspapers refused to print, which Mattie claims had been lobbed at her during their fall tour. The primary witness to the August event and others like it was Mattie's mother, who was residing with the couple. Mattie further claimed that she had been trying to obtain a separation, but that Ernest was planning on denying her that satisfaction, much less any divorce or alimony. Her mother echoed the same sentiment. This did not echo the Ernest Hogan that most people knew, and showed a potentially dark side uncharacteristic of his usual demeanor. With virtually no other witness coming forward, the court was put in the position of deciding the outcome based on the he said/she said testimony during the late February, 1903, trial. It was also suspicious that she was able to continue in shows into early 1903, right up to the opening of the initial Smart Set appearance in New York City in late February just a day before Hogan's arrest. However, in spite this relatively misogynistic era in history, Mattie's case was given some due consideration. That Hogan had filed for voluntary bankruptcy just three weeks prior was also considered in the balance of charges, and as a potential trigger for Mattie's action six months after the fact.

The primary witness to the August event and others like it was Mattie's mother, who was residing with the couple. Mattie further claimed that she had been trying to obtain a separation, but that Ernest was planning on denying her that satisfaction, much less any divorce or alimony. Her mother echoed the same sentiment. This did not echo the Ernest Hogan that most people knew, and showed a potentially dark side uncharacteristic of his usual demeanor. With virtually no other witness coming forward, the court was put in the position of deciding the outcome based on the he said/she said testimony during the late February, 1903, trial. It was also suspicious that she was able to continue in shows into early 1903, right up to the opening of the initial Smart Set appearance in New York City in late February just a day before Hogan's arrest. However, in spite this relatively misogynistic era in history, Mattie's case was given some due consideration. That Hogan had filed for voluntary bankruptcy just three weeks prior was also considered in the balance of charges, and as a potential trigger for Mattie's action six months after the fact.

The primary witness to the August event and others like it was Mattie's mother, who was residing with the couple. Mattie further claimed that she had been trying to obtain a separation, but that Ernest was planning on denying her that satisfaction, much less any divorce or alimony. Her mother echoed the same sentiment. This did not echo the Ernest Hogan that most people knew, and showed a potentially dark side uncharacteristic of his usual demeanor. With virtually no other witness coming forward, the court was put in the position of deciding the outcome based on the he said/she said testimony during the late February, 1903, trial. It was also suspicious that she was able to continue in shows into early 1903, right up to the opening of the initial Smart Set appearance in New York City in late February just a day before Hogan's arrest. However, in spite this relatively misogynistic era in history, Mattie's case was given some due consideration. That Hogan had filed for voluntary bankruptcy just three weeks prior was also considered in the balance of charges, and as a potential trigger for Mattie's action six months after the fact.

The primary witness to the August event and others like it was Mattie's mother, who was residing with the couple. Mattie further claimed that she had been trying to obtain a separation, but that Ernest was planning on denying her that satisfaction, much less any divorce or alimony. Her mother echoed the same sentiment. This did not echo the Ernest Hogan that most people knew, and showed a potentially dark side uncharacteristic of his usual demeanor. With virtually no other witness coming forward, the court was put in the position of deciding the outcome based on the he said/she said testimony during the late February, 1903, trial. It was also suspicious that she was able to continue in shows into early 1903, right up to the opening of the initial Smart Set appearance in New York City in late February just a day before Hogan's arrest. However, in spite this relatively misogynistic era in history, Mattie's case was given some due consideration. That Hogan had filed for voluntary bankruptcy just three weeks prior was also considered in the balance of charges, and as a potential trigger for Mattie's action six months after the fact.In the end, the parties made up and the charges were ultimately dropped or at least settled. Ernest and Mattie would work together on stage through most of 1903. However, she dropped the name Hogan, a probable indicator of her intention to divorce the star, which she eventually did in 1904. The Smart Set company, which Hill sometimes referred to as the "Royal Senegambian Opera Company," cut a swath through the entertainment world throughout 1903, leaving behind many satisfied theater-goers in their wake. For a new production in the fall, The Smart Set took Hogan's Missionary Man song and turned it into an farce for an entire vaudeville act which was well-reviewed throughout its run. Ernest and Mattie also did a duo act at the Orpheum for a while to great acclaim.

Ernest landed in court over a song in 1904 in a case that eventually had some influence not only over future publishing contracts but copyright law for both white and black composers. In November of 1902, Hogan and fellow composer James Tim Brymn signed a three-year contact with the firm of Joseph Stern stating that their increasingly popular works would published exclusively by that firm. In spite of such contracts, jumping from firm to firm was common at that time, and there were loopholes. As a measure of reinforcement, and perhaps a statement of potential mistrust of the composers, they were also asked to spend some time at the firm each day either writing or demonstrating their wares, and at least earning their keep at $10 per week, paid against their royalties.

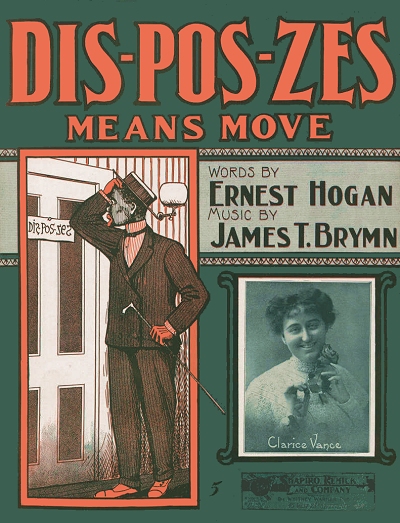

Hogan and Brymn composed D-i-s! P-o-s! Z-e-s! Means Move in early 1904. It was interpolated into a show where it was sung by Clarice Vance. Many theatrical companies or producers had standing deals with certain publishers that they felt trumped the contracts of their composers, and even some interpolated works ended up under another emblem once they were on Broadway. D-i-s! P-o-s! Z-e-s! was evidently turned down by Stern, then offered to Shapiro, Remick & Company in March of 1904, an action that Shapiro found to be in violation of the contract he held with the composers. A loophole in their contract, particularly in Brymns, that they could terminate during specific time periods if two of their pieces weren't published during that period, was found to be the mitigating factor in a 1905 appeal that overturned the original 1904 judgment against Shapiro, Remick. Following that, there were often two sets of contracts for composers concerning pieces published by show producers and those not included in shows. It also helped to better establish rights of contracts and royalty arrangements for composers of color.

Changing the World - One Theater at a Time

Ernest continued with the Smart Set company in 1904, mostly on the road. However, near the end of the year, either because of the legal entanglements, marriage issues, another pending show he had been working on, or other external forces, he abdicated his position to black composer and entertainer Sherman H. Dudley.  In early 1905, Will Dixon, another black composer and conductor, formed the Memphis Students company along with Will Marion Cook. Hogan was brought on as their chief comedian and comic singer. This elite company originally frequented the vaudeville theaters of New York, including Proctor's and Hammerstein's. In 1906 they were reformed as the Tennessee Students and a company of 17 performers launched a musical tour of Europe that lasted into 1907. There have been mentions that he may have been married to a woman named Louise around this time, and she helped him organize the Students, but such mentions were difficult to corroborate in public records and contemporary sources.

In early 1905, Will Dixon, another black composer and conductor, formed the Memphis Students company along with Will Marion Cook. Hogan was brought on as their chief comedian and comic singer. This elite company originally frequented the vaudeville theaters of New York, including Proctor's and Hammerstein's. In 1906 they were reformed as the Tennessee Students and a company of 17 performers launched a musical tour of Europe that lasted into 1907. There have been mentions that he may have been married to a woman named Louise around this time, and she helped him organize the Students, but such mentions were difficult to corroborate in public records and contemporary sources.

In early 1905, Will Dixon, another black composer and conductor, formed the Memphis Students company along with Will Marion Cook. Hogan was brought on as their chief comedian and comic singer. This elite company originally frequented the vaudeville theaters of New York, including Proctor's and Hammerstein's. In 1906 they were reformed as the Tennessee Students and a company of 17 performers launched a musical tour of Europe that lasted into 1907. There have been mentions that he may have been married to a woman named Louise around this time, and she helped him organize the Students, but such mentions were difficult to corroborate in public records and contemporary sources.

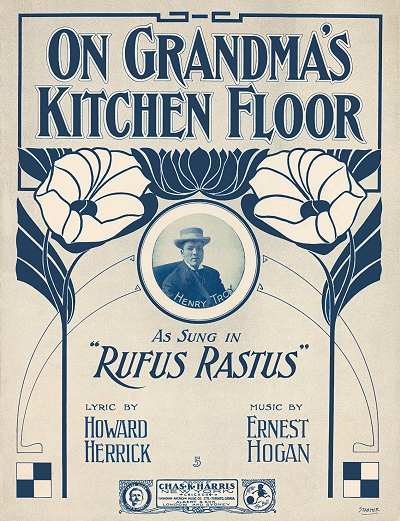

In early 1905, Will Dixon, another black composer and conductor, formed the Memphis Students company along with Will Marion Cook. Hogan was brought on as their chief comedian and comic singer. This elite company originally frequented the vaudeville theaters of New York, including Proctor's and Hammerstein's. In 1906 they were reformed as the Tennessee Students and a company of 17 performers launched a musical tour of Europe that lasted into 1907. There have been mentions that he may have been married to a woman named Louise around this time, and she helped him organize the Students, but such mentions were difficult to corroborate in public records and contemporary sources.Although Ernest had been a part of the Students, he was also concurrently working on another production along with fledgling composer Joe Jordan. From 1902 to 1905 they worked sporadically with William D. Hall on a libretto and Frank Williams as a lyricist on a show that eventually morphed into the musical Rufus Rastus. It debuted off-Broadway in late 1905 and played on Broadway from at the American Theatre, the Metropolis Theatre, then the West End Theatre, between January and March of 1906, with Ernest filling the starring role of the production when he wasn't on the road with the Tennessee Students. Even with a fragmented two month run, Rufus Rastus was considered to be a relative success for black theater on Broadway. While it was not as successful as some of the work written and staged by Will Marion Cook, it was still part of a cluster of shows that set a paradigm for black-oriented stage shows which would not be eclipsed for around two decades.

In spite of his involvement with the Tennessee Students, Hogan signed a five year contract in late 1905, which according to the Music Trade Review of September 2, was with producers Hurtig and Seamon, and which assigned him "to head a company of negro [sic] comedians in a new musical comedy called 'The Funny Folk Minstrels,' by William D. Hall of Philadelphia." For reasons beyond his control, Ernest would not be able fo fulfill the term of that contract. He was stretched thin as it was between all of the projects he was involved with.

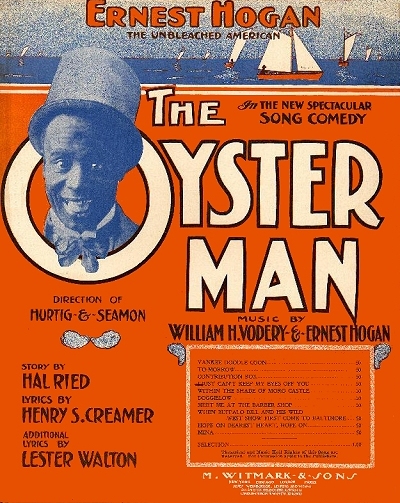

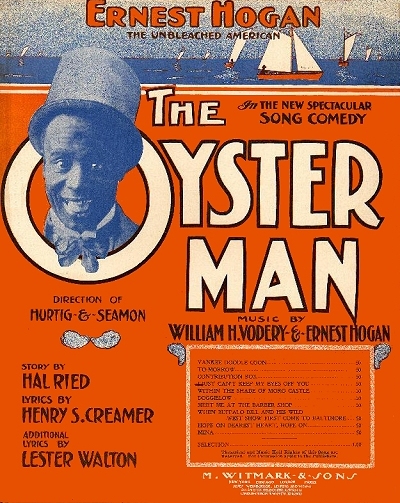

Another one had its genesis while he was with the Students in Chicago, playing at the Pekin Theatre. The moderately successful black comedy team of Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles approached Ernest with a sketch they had written titled The Oyster Man. Hogan showed interest in it, and encouraged them to develop it into a bigger book. He engaged help from lyricist Henry Creamer and Lester Walton, and wrote the music for the production along with Will Vodery. The Oyster Man debuted off-Broadway at the Fourteenth Street Theater on November 25, 1907. It played in a few theaters on and off Broadway through the next month, then went on tour in 1908. However, the tour did not have its star on board, his role having been taken over by John Rucker.

Hogan had become ill with tuberculosis during 1907, and barely survived the first week of The Oyster Man. After a period of recuperation he rejoined the show in Boston, but collapsed not long into that run, an event which closed the production down. He spent much of 1908 in and out of hospitals and sanatoriums. His absence from the stage was also lauded frequently throughout the year. In a regular column written by Walton in the New York Age of October 8, 1908, he noted that Ernest was feeling much better, and that his attending physician said that "the chances are favorable for his ultimate recovery." That same column noted that The Oyster Man was not likely to be resurrected anytime soon, much less any other "colored show." Indeed, not until Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle completed Shuffle Along in the 1920s would there be another successful black-written and produced show on Broadway.

He spent much of 1908 in and out of hospitals and sanatoriums. His absence from the stage was also lauded frequently throughout the year. In a regular column written by Walton in the New York Age of October 8, 1908, he noted that Ernest was feeling much better, and that his attending physician said that "the chances are favorable for his ultimate recovery." That same column noted that The Oyster Man was not likely to be resurrected anytime soon, much less any other "colored show." Indeed, not until Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle completed Shuffle Along in the 1920s would there be another successful black-written and produced show on Broadway.

He spent much of 1908 in and out of hospitals and sanatoriums. His absence from the stage was also lauded frequently throughout the year. In a regular column written by Walton in the New York Age of October 8, 1908, he noted that Ernest was feeling much better, and that his attending physician said that "the chances are favorable for his ultimate recovery." That same column noted that The Oyster Man was not likely to be resurrected anytime soon, much less any other "colored show." Indeed, not until Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle completed Shuffle Along in the 1920s would there be another successful black-written and produced show on Broadway.

He spent much of 1908 in and out of hospitals and sanatoriums. His absence from the stage was also lauded frequently throughout the year. In a regular column written by Walton in the New York Age of October 8, 1908, he noted that Ernest was feeling much better, and that his attending physician said that "the chances are favorable for his ultimate recovery." That same column noted that The Oyster Man was not likely to be resurrected anytime soon, much less any other "colored show." Indeed, not until Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle completed Shuffle Along in the 1920s would there be another successful black-written and produced show on Broadway.Ernest was surrounded by friends and admirers throughout his ordeal. In fact, it was reported by Walton in the January 14, 1909, edition of the New York Age that many of them had recently met at his residence, during which they formed a vaudeville performers organization, the Colored Vaudeville Association, their intent to be a "beneficial and elevating organization." They could also come to the aid of those in need, including their beloved comedian host. However, it was too late to save Reuben Crowdus. Seventeen months after his diagnosis, Reuben succumbed to the tuberculosis on May 20, 1909, in his Bronx residence, surrounded friends and family, including his mother and his attorney. The tributes were grand and well-attended, and St. Benedict Catholic Church made an exception to the rule of not having a funeral on the Sabbath by hosting his on the Sunday following his death. The pallbearers list read like a who's who of the black entertainment world of 1909. He was then sent back to Bowling Green, Kentucky, where he remains to this day.

When the dust settled, Bert Williams became the prime colored comedian of Broadway, including a good long run with the highly regard and entertaining Ziegfeld Follies. Many of the others that he had worked with, including George Walker, would be dead by the early 1910s, either due to their sometimes-reckless lifestyles, or from other external menaces. However, any black "stars" over the next several years would appear in predominately white shows. While many, such as Ford Dabney and James Reese Europe would find a measure of fame as musicians, few would take the stage as performers doing their own brand of material until Sissle, Blake, R.C. McPherson (Cecil Mack) and James P. Johnson came forth in the 1920s with their innovative music. After that, Broadway slowly became homogenized, followed some decades later by Hollywood. Yet for all that Hogan did to forward those of his race, he was haunted to the time of his death by that one piece with that one word, which ironically would not have become nearly as famous if he had not been so engaging when performing All Coons Look Alike to Me.

The question remains as to whether or not Reuben Crowdus of Bowling Green, Kentucky, was the inventor of ragtime, or at least its first major promoter of color. The latter posit is most likely the case, and easy to support. Still, it took well over a century after his birth and nearly as century after his peak for him to be properly recognized outside of a few historical writings. Over the past decade and more, Bowling Green has been promoting their role in black history, touting Ernest Hogan as one of their own. In 2014, just short of 150 years after his birth, a show written by Michael Aman titled The Unbleached American starring Johnny Lee Davenport in the initial production at the Stoneham Theater in the north part of Boston, Massachusetts. There is hope that Ernest Hogan may yet make it to Broadway in a new century.

As for how he was remembered at the time of his death, Lester Walton noted the following in his own assessment of the life of Reuben Crowdus a week after his death:

Ernest Hogan was not what one would term a man of education. But he was a student at all times, a man of common sense, a good judge of human nature, farseeing and philosophical; one void of selfishness, aggressive to a degree, a man of impulses and full of magnetism. His main fault was that, although he knew how to make money, he did not possess the ability to keep it. But that fault was one that worked more to his own detriment than to others, and does not detract one whit from the fact that during life he accomplished great good for his race, and advanced the standing of the colored members of the theatrical profession.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions