Frederick Allen "Kerry" Mills (February 1, 1869 to December 5, 1948) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1891

Flirtation Polka1894

Do You Remember Love?1895

Rastus on ParadeShandon Bells: Two Step March 1896

Happy Days in Dixie: Characteristic MarchRastus on Parade: A Song of Color [1] Shandon Bells: Song [2] 1897

At A Georgia Campmeeting: Cake WalkAt A Georgia Campmeeting: A Song in Black Let Bygones Be Bygones [3] Happy Days in Dixie: A Song in Ebony [3] Sweetheart the Time Will Come [3] 1898

Charity Begins at Home [4]1899

Whistlin' Rufus: A Characteristic CakewalkImpecunious Davis: March and Cakewalk Supposing [5] George, Our Second George (We All Turn Out to Welcome Dear Old Dewey) [5] When Dewey Comes Sailing Home [6] Whistlin' Rufus (The One Man Band): Song [7] 1900

Before the DayKerry Mills Lancers: Themes from Previous Cake Walk and Songs 1902

Harmony Moze: Characteristic Two StepFare Thee Well Molly Darling (At the Call of the Roll I'll be There) [8] In the City of Sighs and Tears [9] A Brand Plucked From the Burning [10] I Know She Waits for Me [10] Marie Magee [11] Hail, Holy Light (The Eternal Dawn) [28] 1903

'Leven Forty-Five from the HotelValse Hèléne Valse Primrose: Les Primevères Petite Causerie (A Quiet Chat) L'amour Aux Bois (Cupid's Bower) Me and Me Banjo Just Remember [That] I Love You [9] Like A Star That Falls From Heaven [10] The Duel of Hearts and Eyes [12] I Think of You [13] 1904

Meet Me In St. Louis, Louis [9]When the Bees are in the Hive [12] Just For The Sake Of Society [12] We'll Be Together When the Clouds Roll By [12] Don't Cry Katie Dear [14] Let's All Go Up to Maud's [15] 1905

A Selection by AndyGood-Bye, Sweet Marie [8] I Think I Could Be Awfully Good to You [8] We'll Be Together when the CLouds Roll By [9] Pretty Mary [9] Watch Where the Crowd Goes By [9] So Long Andy Lee [15] 1906

Old Heidelberg: A Characteristic Two StepWhile the Old Mill Wheel is Turning [8] 1907

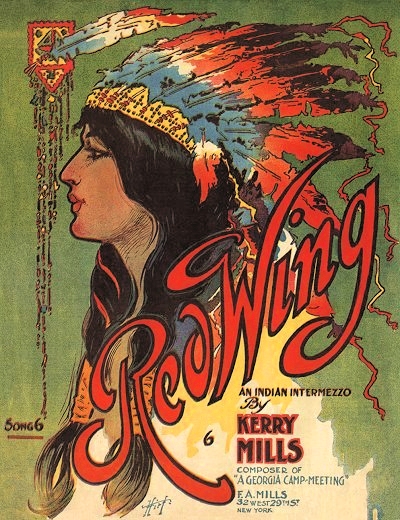

When You Love Her and She Loves YouRed Wing: An Indian Intermezzo Red Wing: An Indian Fable [16] Take Me Around Again [17] Terry, Terry, Terrible Terry [18] 1908

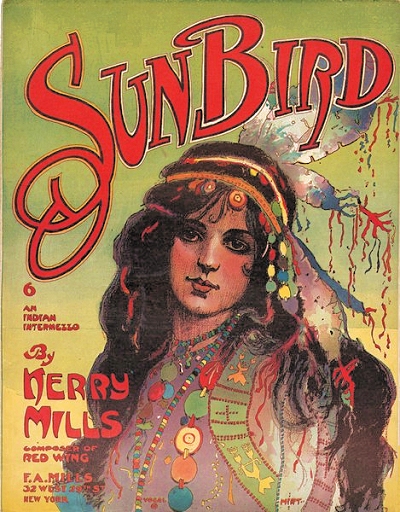

Kerry Mills Barn DanceHallie (A Little Romance) Sweet Sixteens: March Sun Bird: An Indian Intermezzo Stop Making Faces at Me [9] Any Old Port in a Storm [10] If You Were Mine [10] Childhood [12] Sweet Sixteens [12] Sun Bird: Song [16] I'm Tired of Living Without You [17] The Longest Way 'Round is the Sweetest Way Home [18] Under the Chicken Tree [19] 1909

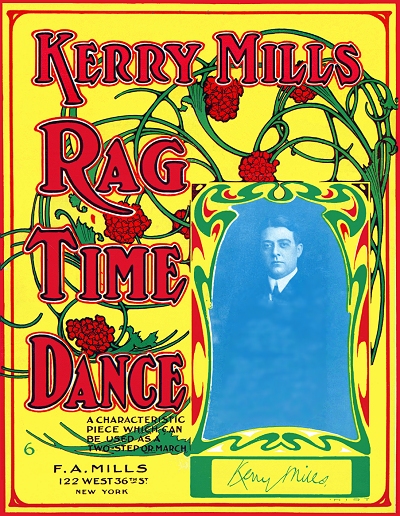

Kerry Mills Rag Time DanceKerry Mills New Barn Dance A Georgia Barn Dance The Scarf Dancer: A Novelty Two Step Lily of the Prairie: Intermezzo Lily of the Prairie: An Indian Fable Sicilian Chimes: A Reverie for Piano That Dreamy Waltz (Cette Valse Revèuse) Ianthe Pass dat Possum: Characteristic March If You But Only Cared, Dear I Want a Little Corner in Your Heart [9] Wreck of the Good Ship, Love [10] Don't Be an Old Maid, Molly [12] I'm Afraid to Sleep Alone [12] Lovins Dovins [12] Where Were You Last Night? [12] Yes She Did (Try to Get Out of Here Tonight) [12] Highland Mary [12] Pass dat Possum: Song [12] When a Pal of Mine Steals a Gal of Mine [12] You'll Have to Ask My Mother [12] We're Almost Home [16] I'd Like to Be the Fellow That Girl is Waiting For [17] I'd Like to Have Your Photograph [17] Take Me Out for a Joy Ride [18] Papa, Please Buy Me an Airship [18] Comical Eyes [20] Margarita [21] It Is Hard to Kiss Your Sweetheart When the Last Kiss Means Good-Bye [23] You're For Me When You're Sweet Sixteen [23] 1910

Valley Flower: IntermezzoValley Flower: Song That Fascinating Ragtime Glide I Want a Man I Can Love Kerry Mills Palmetto Slide Love Thoughts Here Comes the Band |

1910 (Cont)

Marie AnnMy Friend "Jim-a-da-Jeff" Nantucket Kisses for Sale The Wyoming Prance: A Rag Time Two Step Play That Lovey Dove Waltz Some More What Would Become of New York Town (If Broadway Wasn't There) [9] I've Lost My Nannie [9] I'll Have My Opera on the East Side (When Maggie Sings the Old Songs) [9,20] He's Nothing to Me [17] They All Gave Me Something to Remember Them By [17] How Many Have You Told That To? [17] A Little Bit of Jolly Goes a Long, Long Way [20] Father is a Champion Working Man [20] Look Out I'm Going to Steal You [21] I've a Great Big Heart With a Great Big Love [21] You Can't Make Me Stop Loving You [21] That Fascinating Ragtime Glide: Song [21] When the Girl Who Can't Forget You Wants to Know If You've Forgot [23] The Fascinating Widow [24] Rag de Paree [25] Don't You Care Litle Girl? [25] I'll Build a Fence Around You [25] 1911

The Old Town is Looking Mighty GoodTonight [10] You've Got the Wrong Number But the Right Girl [10] The Fascinating Widow: Musical Put Your Arms Around Me [25] Everybody Likes a College Girl [25] The Eltinge Moorish Dance Waltz for Piano I'm Only a Fair Sun Bather [24] Love is the Theme of My Dream [24] Don't You Make a Noise [24] Valse Julian [24] Always Keep a Fellow Guessing (If You Want His Love) [24] I'm to Be a Blushing Bride [25] To Take a Dip in the Ocean [25] The Rag Time College Girl [24] 1912

If You Go Home to Your Husband, I'll Haveto Go Home to My Wife When You Get it Tuned Up, Play Us Something [21] 1913

You're the Fairest Little Daisy that Grows inthe Garden [26] 1914

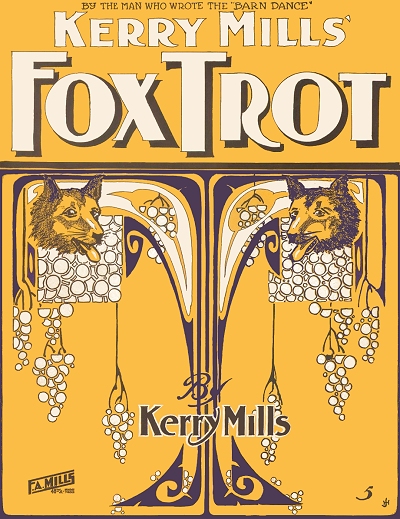

Kerry Mills Turkey TrotKerry Mills Fox Trot Me and Mandy Lee [26] Who's Your Lady Friend? [26] She's Dancing Her Heart Away [26] The Kingdom of Love [26] When I Come Back [26] (You'll Find it Out) Mighty Soon [26] 1915

Kerry Mills Cake WalkPeace Everlasting: March (I'll Come Back To You) When It's All Over [27] Cakewalk with Me [29] My Rose of Another Day [31] Why Do We Love the Baby's Hands? [31] My Consolation [31] My Sweetest Day [30,31] Caddie [32] It's a Long Time Till We Meet Again [32] Heaven Will Be More Beatiful Now That You Are There [32] 1916

The Owl's CotillionDaisies in the Dell My Heart and I A Little Bird Told Me 1918

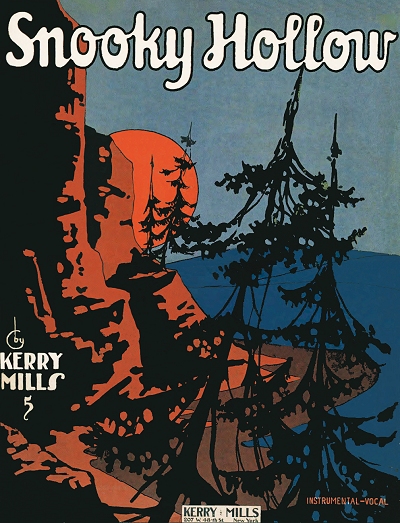

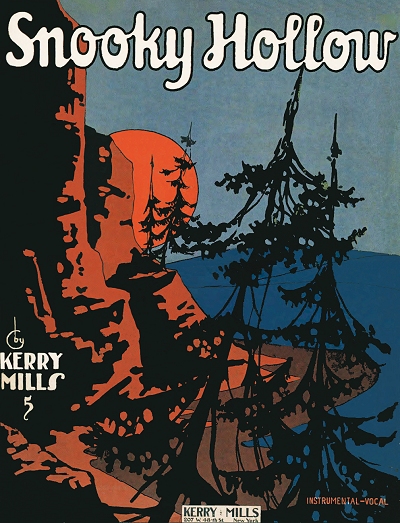

Snooky Hollow: SongTeach Me to Be a Brave Soldier, One Like My Daddy Is Now 1919

The Geisha Girl in TokioTokio: Fox Trot on Chorus from Geisha Girl Floating Down the Old Monongahela Under the Teakwood Tree 1920

Spooney Hollow1921

Della-RheaSomebody: Song-Trot 1922

Lovable Eyes: Song-TrotStar of Dawn: Reverie

1. w/George F. Marion

2. w/Genevieve McCloud 3. w/Charles Shackford 4. w/George Taggart 5. w/Arthur Trevelyan 6. w/John Langdon Heaton 7. w/W. Murdock Lind 8. w/Will D. Cobb 9. w/Andrew B. Sterling 10. w/Arthur J. Lamb 11. w/George M. Cohan 12. w/Alfred Bryan 13. w/John Ernest McCann 14. w/Jack Tarr 15. w/Joseph C. Farrell 16. w/Thurland Chattaway 17. w/Edward Rose 18. w/Ren Shields 19. w/Irving Jones 20. w/Bartley C. Costello 21. w/Edgar Leslie 22. w/George W. Meyer 23. w/Robert F. Roden 24. w/E. Ray Goetz 25. w/Sam M. Lewis 26. w/Louis Wolfe Gilbert 27. w/Lew Brown 28. w/W.C. Kreusch 29. w/Arthur Jackson 30. w/Andre de Takacs 31. as Avery St Clair 32. as Pierre Morin |

Frederick Allen Mills enjoyed a career with a true duality, and great success in both facets of his years as a composer (Kerry Mills) and a publisher (F.A. Mills). Somehow he managed to keep these facets separate as he did his identities, yet made it all work together. Not much has been written on Mills beyond his role in popularizing cakewalks and his three biggest hits, but this account will hopefully fill out some more details about his life and times in the music business.

Frederick was born to Frederick Mills and Annie Lund in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania less than half a decade after the end of the Civil War. He had two sisters, one older, Florence (1863), and one younger, Caroline (1877). His father Fred was listed as a lecturer, but in what field is unclear. Mr. Mills toured often and spent quite a bit of time away from home, as is evidenced in various city and local census listings. The 1870 census taken in Philadelphia showed Annie residing with two of her sisters, as well as Florence and baby Frederick, while her husband was not listed. Mills moved his family to Detroit, Michigan in the mid-1870s, where Carrie was born, and they are found there in the 1880 census.

According to an early biography of Mills, he began studying music at age eight, with his main focus initially on the violin, as per his father's wishes. By the time the elder Frederick died around 1884, his musical performances helped to contribute to the family income. In his late teens Frederick claims he was given the position of the musical director of the Casino Roller Rink in Detroit, managing and directing an orchestra. Around 1887 he was awarded a scholarship that allowed him to attend the Chicago Musical College, run by Florenz Ziegfeld, Sr., from that time through at least 1892. For at least the last two years Mills was also an instructor at the institution. For extra income he played second violin with the Jacobsohn String Quartette, a university sponsored group under a Professor Jacobsohn, and claimed to be one of the more notable groups of that kind in the country. In 1891 his first known published work, Flirtation Polka, was issued in Oskaloosa, Iowa, by the C.L Barnhouse Company.

For extra income he played second violin with the Jacobsohn String Quartette, a university sponsored group under a Professor Jacobsohn, and claimed to be one of the more notable groups of that kind in the country. In 1891 his first known published work, Flirtation Polka, was issued in Oskaloosa, Iowa, by the C.L Barnhouse Company.

For extra income he played second violin with the Jacobsohn String Quartette, a university sponsored group under a Professor Jacobsohn, and claimed to be one of the more notable groups of that kind in the country. In 1891 his first known published work, Flirtation Polka, was issued in Oskaloosa, Iowa, by the C.L Barnhouse Company.

For extra income he played second violin with the Jacobsohn String Quartette, a university sponsored group under a Professor Jacobsohn, and claimed to be one of the more notable groups of that kind in the country. In 1891 his first known published work, Flirtation Polka, was issued in Oskaloosa, Iowa, by the C.L Barnhouse Company.After his schooling in Chicago, Frederick returned to Detroit to teach violin and play for concert engagements. He procured a teaching position at the University School of Music in Ann Arbor in 1892, and according to his own recollection in a 1909 biography became head of the violin department there, concertizing on the instrument within the next couple of years. This appears to have been a separate campus indirectly associated with Michigan University, as Dr. Edward Berlin has noted that there was no music department at the Ann Arbor campus at that time. (The University of Michigan School of Music, Theater and Dance notes on its website that it was established in 1880, separate from the parent university itself until around 1929.) It was during this period in his life that Frederick Mills encountered the cakewalk while touring as a musician.

The Cakewalk, both the dance and the musical form, was somewhat untamed at that time. While there are many different elements that contributed to its origin and development, the essence of it was a high stepping dance created by blacks who were actually imitating in exaggeration some of the wild and fancy steps they had seen white people execute. It was also the name of the social event, where each couple dressed in their finest clothes. The couple who won with the best walk would literally "take the cake," the prize that was traditional at these events, thus the name.

Mills worked with it to create a better template for both the rhythms and form of the dance. His first cakewalk was reportedly completed, or at least copyrighted in 1893 or 1894. Rastus on Parade is considered by many historians to be the first syncopated cakewalk composed. It is more likely that it was the first one that was notated in a coherent manner to make it viable to publish. In spite of this, Mills found rejection by a number of publishers who did not care for it or know what to do with the piece. However, he believed in both Rastus on Parade and the culture it represented. Mills was said to have adopted the cakewalk as a refined musical protest to the vulgar racial stereotypes that were becoming common in the many "coon songs" that were making the rounds at that time. By 1895, finding this exciting new form more appealing than the classical music he had been performing, and frustrated with the treatment he was getting from publishers, Mills decided to move to New York City and start his own firm. It was there that both the firm of F.A. Mills and the composer Kerry Mills, a derivative of a nickname for Frederick, were born.

In spite of this, Mills found rejection by a number of publishers who did not care for it or know what to do with the piece. However, he believed in both Rastus on Parade and the culture it represented. Mills was said to have adopted the cakewalk as a refined musical protest to the vulgar racial stereotypes that were becoming common in the many "coon songs" that were making the rounds at that time. By 1895, finding this exciting new form more appealing than the classical music he had been performing, and frustrated with the treatment he was getting from publishers, Mills decided to move to New York City and start his own firm. It was there that both the firm of F.A. Mills and the composer Kerry Mills, a derivative of a nickname for Frederick, were born.

In spite of this, Mills found rejection by a number of publishers who did not care for it or know what to do with the piece. However, he believed in both Rastus on Parade and the culture it represented. Mills was said to have adopted the cakewalk as a refined musical protest to the vulgar racial stereotypes that were becoming common in the many "coon songs" that were making the rounds at that time. By 1895, finding this exciting new form more appealing than the classical music he had been performing, and frustrated with the treatment he was getting from publishers, Mills decided to move to New York City and start his own firm. It was there that both the firm of F.A. Mills and the composer Kerry Mills, a derivative of a nickname for Frederick, were born.

In spite of this, Mills found rejection by a number of publishers who did not care for it or know what to do with the piece. However, he believed in both Rastus on Parade and the culture it represented. Mills was said to have adopted the cakewalk as a refined musical protest to the vulgar racial stereotypes that were becoming common in the many "coon songs" that were making the rounds at that time. By 1895, finding this exciting new form more appealing than the classical music he had been performing, and frustrated with the treatment he was getting from publishers, Mills decided to move to New York City and start his own firm. It was there that both the firm of F.A. Mills and the composer Kerry Mills, a derivative of a nickname for Frederick, were born.Rastus on Parade actually made a fairly good splash in its initial run, and through good marketing, Mills managed to get it onto vaudeville stages around Manhattan, and possibly even the entertainment districts of Coney Island. It was not rejected by the black population either, some of who found it refreshing to have some form of their music in print in a positive way. In short order, Mills hired a lyricist to make it into a song, a move that furthered the appeal of the piece now that it was singable. He also sought out more similar material to be published under his new label, and soon became a friend to many on the developing Broadway stage who needed a home for their collective works. Within two years of his launching Mills had a decent catalog of marches, two steps and waltzes, plus early cakewalk songs by stars of the vaudeville houses, including Ben Harney. He also appeared to be a champion of black composers in vaudeville who were writing their own songs and cakewalks. Other items in the Mills catalog included ballads, such as the maudlin hit Asleep in the Deep. But Mills felt he needed a follow-up hit of his own to move things forward.

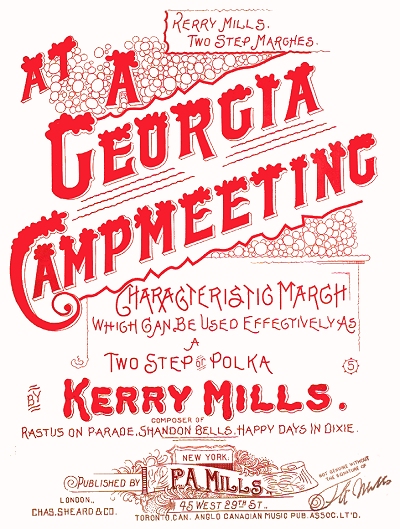

It was in 1897 that Mills composed the cakewalk that would become the admired model for the musical form for the business, and would make it the first true dance sensation of New York's fabled Tin Pan Alley. At a Georgia Campmeeting (originally titled A Georgia Campmeeting with "At" added as an afterthought) was his attempt to further the music form while explaining its role. In the forward to the piece Frederick wrote: "This march was not intended to be part of the Religious Exercises... but when the young folks got together, they felt as if they needed some amusement. A Cake Walk was suggested, and held in a quiet place near by - hence this music." It became the template he had hoped for, but not without a second bout of rejections as he tried to place the piece with larger publishers for better distribution. Undaunted, he released it under his own label and got it easily placed on stages throughout the Eastern seaboard.

At a Georgia Campmeeting (originally titled A Georgia Campmeeting with "At" added as an afterthought) was his attempt to further the music form while explaining its role. In the forward to the piece Frederick wrote: "This march was not intended to be part of the Religious Exercises... but when the young folks got together, they felt as if they needed some amusement. A Cake Walk was suggested, and held in a quiet place near by - hence this music." It became the template he had hoped for, but not without a second bout of rejections as he tried to place the piece with larger publishers for better distribution. Undaunted, he released it under his own label and got it easily placed on stages throughout the Eastern seaboard.

At a Georgia Campmeeting (originally titled A Georgia Campmeeting with "At" added as an afterthought) was his attempt to further the music form while explaining its role. In the forward to the piece Frederick wrote: "This march was not intended to be part of the Religious Exercises... but when the young folks got together, they felt as if they needed some amusement. A Cake Walk was suggested, and held in a quiet place near by - hence this music." It became the template he had hoped for, but not without a second bout of rejections as he tried to place the piece with larger publishers for better distribution. Undaunted, he released it under his own label and got it easily placed on stages throughout the Eastern seaboard.

At a Georgia Campmeeting (originally titled A Georgia Campmeeting with "At" added as an afterthought) was his attempt to further the music form while explaining its role. In the forward to the piece Frederick wrote: "This march was not intended to be part of the Religious Exercises... but when the young folks got together, they felt as if they needed some amusement. A Cake Walk was suggested, and held in a quiet place near by - hence this music." It became the template he had hoped for, but not without a second bout of rejections as he tried to place the piece with larger publishers for better distribution. Undaunted, he released it under his own label and got it easily placed on stages throughout the Eastern seaboard.Within months the cakewalk in general had taken over youth and young adults in both black and white communities around the country, creating giddiness for the younger generation while causing some shock and concern for the older generation. Both At a Georgia Campmeeting and Rastus were made famous by the teams of Williams and Walker Genaro and Bailey on the vaudeville stage. There were many imitators of Mills, and they were often compared to At a Georgia Campmeeting. Many met the challenge, but somehow his was among the most memorable of melodies. A song version soon followed. It didn't hurt that Mills made a couple of deft acquisitions for his catalog either. One in particular, Asleep in the Deep, by Arthur J. Lamb and H.W. Petrie, was a mega hit, especially with stage singers in the basso-profundo field given its final sinking notes. By the end of 1897, the music industry had at least some idea that F.A. Mills was a force to be reckoned with.

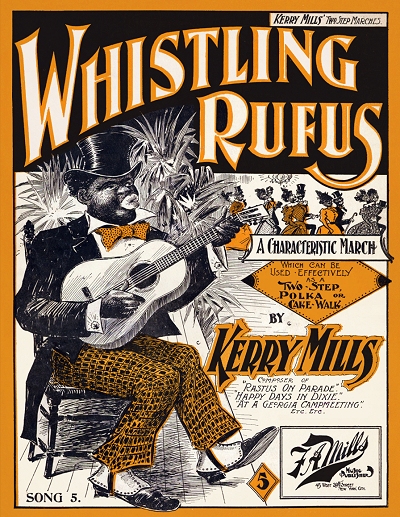

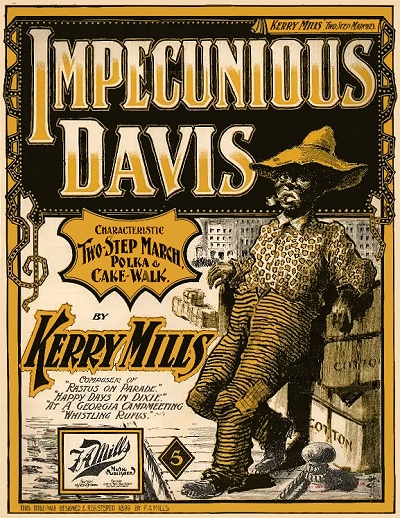

In early 1899 another Kerry Mills work, Whistling Rufus, did well in the stores as a cakewalk which was soon followed by an unfortunate "coon song" version. In either guise, it created so much buzz that advance orders for his next announced piece, the colorfully named Impecunious Davis, were an unheard of 256,000 copies. It ultimately sold around 750,000 copies, a first rate showing for an instrumental piece. In just four years, Mills, through his own compositions and those of others he had published, had created a craze as well as a place of some respectability for what many considered to be an Afro-American music form. Starting in 1899, some of his cakewalks found their way onto cylinders and discs, including recordings by banjoist Vess L. Ossman and the band of John Philip Sousa. Historian Galen Wilkes points out that Whistling Rufus was probably committed to cylinders and discs many more times during the early 20th century than At a Georgia Campmeeting. In a span of around four years, Frederick Mills as Kerry had managed to make what was considered to be a black music safe for consumption by a white audience.

In either guise, it created so much buzz that advance orders for his next announced piece, the colorfully named Impecunious Davis, were an unheard of 256,000 copies. It ultimately sold around 750,000 copies, a first rate showing for an instrumental piece. In just four years, Mills, through his own compositions and those of others he had published, had created a craze as well as a place of some respectability for what many considered to be an Afro-American music form. Starting in 1899, some of his cakewalks found their way onto cylinders and discs, including recordings by banjoist Vess L. Ossman and the band of John Philip Sousa. Historian Galen Wilkes points out that Whistling Rufus was probably committed to cylinders and discs many more times during the early 20th century than At a Georgia Campmeeting. In a span of around four years, Frederick Mills as Kerry had managed to make what was considered to be a black music safe for consumption by a white audience.

In either guise, it created so much buzz that advance orders for his next announced piece, the colorfully named Impecunious Davis, were an unheard of 256,000 copies. It ultimately sold around 750,000 copies, a first rate showing for an instrumental piece. In just four years, Mills, through his own compositions and those of others he had published, had created a craze as well as a place of some respectability for what many considered to be an Afro-American music form. Starting in 1899, some of his cakewalks found their way onto cylinders and discs, including recordings by banjoist Vess L. Ossman and the band of John Philip Sousa. Historian Galen Wilkes points out that Whistling Rufus was probably committed to cylinders and discs many more times during the early 20th century than At a Georgia Campmeeting. In a span of around four years, Frederick Mills as Kerry had managed to make what was considered to be a black music safe for consumption by a white audience.

In either guise, it created so much buzz that advance orders for his next announced piece, the colorfully named Impecunious Davis, were an unheard of 256,000 copies. It ultimately sold around 750,000 copies, a first rate showing for an instrumental piece. In just four years, Mills, through his own compositions and those of others he had published, had created a craze as well as a place of some respectability for what many considered to be an Afro-American music form. Starting in 1899, some of his cakewalks found their way onto cylinders and discs, including recordings by banjoist Vess L. Ossman and the band of John Philip Sousa. Historian Galen Wilkes points out that Whistling Rufus was probably committed to cylinders and discs many more times during the early 20th century than At a Georgia Campmeeting. In a span of around four years, Frederick Mills as Kerry had managed to make what was considered to be a black music safe for consumption by a white audience.In the 1900 census, Frederick was shown living in Manhattan with his recently widowed mother and his sisters, listed as a publisher of music. He had also purchased a ranch near Greenwood Lake in southern New York State where he enjoyed leisure activities like quail hunting and fishing. In early 1900, Mills and his business partner William C. Kreusch incorporated as The Mills Supply Company of New York, with an initial capital stock of $15,000. Their intent was to deal in sheet music, books and novelties, and they established the firm at 48 West Twenty-ninth street in Tin Pan Alley near mid-town Manhattan. The imprint on the sheets remained as F.A. Mills.

Among those engaged to promote Mills songs on stage was six-year-old James Duffy, who with his father had a mildly popular vaudeville act on the B.F. Keith Circuit and a regular gig at Tony Proctor's theater. Another was prominent ballad singer Thomas F. Kelley. In a move to also promote the instrumental qualities of Mills publications, a catalog of first violin and Bb cornet parts was released of virtually everything song they offered. Even though At A Georgia Campmeeting was meeting with continuing success, one song from 1900 gave the Mills house a great deal of visibility, The Fatal Rose of Red by J. Fred Helf. Maudlin ballads were still in style, and this one took the New York stages and parlors by storm for a time.

Another was prominent ballad singer Thomas F. Kelley. In a move to also promote the instrumental qualities of Mills publications, a catalog of first violin and Bb cornet parts was released of virtually everything song they offered. Even though At A Georgia Campmeeting was meeting with continuing success, one song from 1900 gave the Mills house a great deal of visibility, The Fatal Rose of Red by J. Fred Helf. Maudlin ballads were still in style, and this one took the New York stages and parlors by storm for a time.

Another was prominent ballad singer Thomas F. Kelley. In a move to also promote the instrumental qualities of Mills publications, a catalog of first violin and Bb cornet parts was released of virtually everything song they offered. Even though At A Georgia Campmeeting was meeting with continuing success, one song from 1900 gave the Mills house a great deal of visibility, The Fatal Rose of Red by J. Fred Helf. Maudlin ballads were still in style, and this one took the New York stages and parlors by storm for a time.

Another was prominent ballad singer Thomas F. Kelley. In a move to also promote the instrumental qualities of Mills publications, a catalog of first violin and Bb cornet parts was released of virtually everything song they offered. Even though At A Georgia Campmeeting was meeting with continuing success, one song from 1900 gave the Mills house a great deal of visibility, The Fatal Rose of Red by J. Fred Helf. Maudlin ballads were still in style, and this one took the New York stages and parlors by storm for a time.While Frederick was riding high on his success as both a publisher and composer, it could easily have been a short-lived wave because only three years after he made the cakewalk a staple, piano ragtime and ragtime songs with their more complex and varied rhythms were starting to encroach on the rapidly dating cakewalk. He also had many New York and Chicago performers promoting his pieces, and composer Pete Carroll was an active staff member who was apparently on good terms with many Manhattan performers, getting them to endorse the Mills output. Another member added in 1901 was Frederick J. Hamill who migrated from a position at the Windsor Music Company. Singer Bert Morphy also signed on in 1901, but by the end of the year he would instead go to work for rival publisher E.T. Paull. Among his top employees was Maxwell Silver who ardently promoted the firm. Silver stayed with the firm until its eventual demise in 1915. Mills himself as a composer did not respond immediately to evolving musical trends, but he managed to slip some rags and rag songs into his catalog to help keep it current. In 1902, his Harmony Mose provided at least one entry from Kerry Mills that could be considered a rag. Finally in January of 1902, Mills filed an incorporation to publish music, with his company officially renamed as Kerry Mills Inc.

In 1902, his Harmony Mose provided at least one entry from Kerry Mills that could be considered a rag. Finally in January of 1902, Mills filed an incorporation to publish music, with his company officially renamed as Kerry Mills Inc.

In 1902, his Harmony Mose provided at least one entry from Kerry Mills that could be considered a rag. Finally in January of 1902, Mills filed an incorporation to publish music, with his company officially renamed as Kerry Mills Inc.

In 1902, his Harmony Mose provided at least one entry from Kerry Mills that could be considered a rag. Finally in January of 1902, Mills filed an incorporation to publish music, with his company officially renamed as Kerry Mills Inc.Two of the company's professional managers left the firm in 1901. The first was Paul J. Knox who had been with Mills since he moved to New York. The other, Charles Gebest, left the company to manage The Four Cohans. This worked out in the publisher's favor, however, as the Mills catalog got another boost around this time with addition of Broadway whiz kid George M. Cohan, who had recently separated from his family to strike out on his own. Cohan started publishing his songs with Mills over the next several years. By the time his big hits George Washington Jr. and Forty Five Minutes from Broadway were produced, F.A. Mills had sheet music in homes all around the United States. But there was one particular part of the U.S. that would be his next focus.

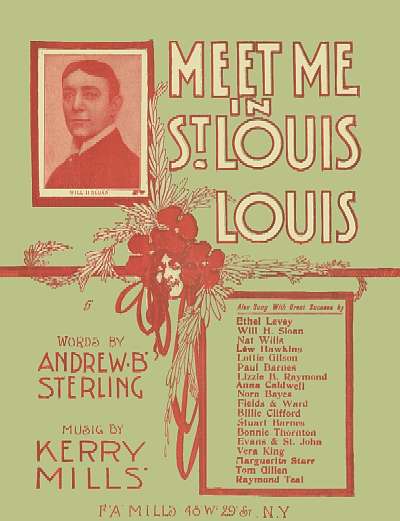

Everybody was talking about the fair. That was the 1904 Louis and Clark World Exposition in St. Louis, originally due to open in 1903, but due to technical issues, such as the necessity of building a power plant for the millions of lights around the fairgrounds, was delayed by nearly a year. This only added to the allure, and for composers all over, the opportunity to capitalize on the buzz around this must-see event. While there were many fine marches and rags in print by opening day, as well as songs extolling the joys of strolling down the Entertainment Pike, somehow Mills and his infrequent partner Andrew B. Sterling hit upon the right formula. Their song Meet Me In St. Louis, Louis, a pleasant comic waltz with a gaggle of extra verses added for good measure, almost instantly became a national hit due to its simplicity and memorable nature. To cap things off, that and some of his other pieces, like Me and Me Banjo, were recorded on Victor by the band of Sousa alumni Arthur Pryor, and many other early recording artists, including Billy Murray. Mills had repeated the success of Georgia Campmeeting in an even shorter time span, and the piece was quickly adopted as the unofficial anthem of the sensational 1904 event. It was natural, of course, that he attend the fair, which he did in the summer of 1904.

and the piece was quickly adopted as the unofficial anthem of the sensational 1904 event. It was natural, of course, that he attend the fair, which he did in the summer of 1904.

and the piece was quickly adopted as the unofficial anthem of the sensational 1904 event. It was natural, of course, that he attend the fair, which he did in the summer of 1904.

and the piece was quickly adopted as the unofficial anthem of the sensational 1904 event. It was natural, of course, that he attend the fair, which he did in the summer of 1904.For the next two years it appears that Mills was more Frederick than Kerry, concentrating on the publishing end of the business, which was going well in Manhattan and beyond. He had officially become a part of what was now being called "Tin Pan Alley," the lower Manhattan song factory comprised of many recently formed houses, including Jerome H. Remick, Harry Von Tilzer, and Ted Snyder. Mills, operating at that time on West 29th Street, would have his next hit in 1907, reviving him in a big way. Ever since Hiawatha by Charles N. Daniels (as Neil Moret) was published in 1902, and in spite of the fact it was named for the town, not the Native American prince, so-called "Indian-Themed" tunes had been increasingly in vogue. While a couple of these had appeared in the Mills catalog, there were none by the publisher/composer himself. This was remedied with the publication of Red Wing: An Indian Intermezzo early in the year, a piece that has similarities to The Merry Peasant by Robert Schumann, which may have served merely as inspiration. It was quickly followed by Red Wing: An Indian Fable with lyrics added by Thurland Chattaway. This was further supplemented by an edition with a quartet rendition of the chorus appended to the song. The beautiful Hirt cover helped propel this piece in all its forms to the front of the pack, where it remained for many years. A century and more later, Red Wing is among the most popular, and most singable of the songs from this genre. The following year, a Native American girl from the Winnebago reservation was breaking into films, and trying to lay claim as the inspiration for the song, as her name was Princess Redwing. While there is no definitive evidence as to her connection to either way, the publicity did help to sell even more copies well beyond the normal distribution circuit of F.A. Mills Music.

While there is no definitive evidence as to her connection to either way, the publicity did help to sell even more copies well beyond the normal distribution circuit of F.A. Mills Music.

While there is no definitive evidence as to her connection to either way, the publicity did help to sell even more copies well beyond the normal distribution circuit of F.A. Mills Music.

While there is no definitive evidence as to her connection to either way, the publicity did help to sell even more copies well beyond the normal distribution circuit of F.A. Mills Music.In the summer of 1907 Frederick's uncle died, leaving behind a considerable estate of around $600,000 that was shared between him and his sister. Some of it was invested into his own firm, but much of it would disappear into debt over the next several years. He also entered into an enterprise with four other publishers, creating The American Music Stores, a large retail outlet, which opened on 40th Street in early June. Mills was president of the short-lived company. The goal was to combat the wanton price cutting of department stores and five and dime stores who often used music as a loss leader, usually to the detriment of dedicated music stores and the publishers. A similar operation, United States Music Stores, was attempted by another cadre of publishers around the same time. Neither lasted terribly long, with sales reverting back to small music stores and the usual retail outlets.

After somewhat of a break following Red Wing, Mills was inspired to compose again, as his output increases from 1908 to 1910. There are also indications that he was able to hire more competent help to run the business and decision side of his publishing house, giving him more time to compose. In May of 1908, Max Silver went out to the Pacific Coast to try and secure better sales in the growing region. As reported in the trades, "There can be no question that he will receive a hearty welcome wherever he makes up his mind to stay over, as he is essentially a 'good fellow,' as well as a first-class entertainer."

Following the success of Red Wing, Mills as Kerry tried again in 1908 with Sun Bird, which did not move nearly as well. There was a setback to the firm in the second week of December, 1908, when a fire destroyed the general offices and much of the unshipped music stock which was stored on the upper floors. This forced the firm to move to a new location in a hurry in order to get back to business. In 1909 he tried his hand at the Native American genre again with Lily of the Prairie in both intermezzo and song form, resulting in a similar tepid response as that given for Sun Bird. Going back to the style which gave him his initial success, Mills penned Kerry Mills Rag Time Dance and A George Barn Dance, which appeared to give the music consumer more of what they were looking for - easy to play and melodic foot stompers suitable for dancing. Frederick also stepped up his songwriting, with a number of contributions featuring lyrics of Alfred Bryan, a busy man in the music business at that time. There were no big hits, but man of their songs were respectable sellers, as indicated by the volume of remaining copies. For reasons that are unclear, their composing relationship appears to have ended in 1909, as no Mills/Bryan songs are found in later years.

This forced the firm to move to a new location in a hurry in order to get back to business. In 1909 he tried his hand at the Native American genre again with Lily of the Prairie in both intermezzo and song form, resulting in a similar tepid response as that given for Sun Bird. Going back to the style which gave him his initial success, Mills penned Kerry Mills Rag Time Dance and A George Barn Dance, which appeared to give the music consumer more of what they were looking for - easy to play and melodic foot stompers suitable for dancing. Frederick also stepped up his songwriting, with a number of contributions featuring lyrics of Alfred Bryan, a busy man in the music business at that time. There were no big hits, but man of their songs were respectable sellers, as indicated by the volume of remaining copies. For reasons that are unclear, their composing relationship appears to have ended in 1909, as no Mills/Bryan songs are found in later years.

This forced the firm to move to a new location in a hurry in order to get back to business. In 1909 he tried his hand at the Native American genre again with Lily of the Prairie in both intermezzo and song form, resulting in a similar tepid response as that given for Sun Bird. Going back to the style which gave him his initial success, Mills penned Kerry Mills Rag Time Dance and A George Barn Dance, which appeared to give the music consumer more of what they were looking for - easy to play and melodic foot stompers suitable for dancing. Frederick also stepped up his songwriting, with a number of contributions featuring lyrics of Alfred Bryan, a busy man in the music business at that time. There were no big hits, but man of their songs were respectable sellers, as indicated by the volume of remaining copies. For reasons that are unclear, their composing relationship appears to have ended in 1909, as no Mills/Bryan songs are found in later years.

This forced the firm to move to a new location in a hurry in order to get back to business. In 1909 he tried his hand at the Native American genre again with Lily of the Prairie in both intermezzo and song form, resulting in a similar tepid response as that given for Sun Bird. Going back to the style which gave him his initial success, Mills penned Kerry Mills Rag Time Dance and A George Barn Dance, which appeared to give the music consumer more of what they were looking for - easy to play and melodic foot stompers suitable for dancing. Frederick also stepped up his songwriting, with a number of contributions featuring lyrics of Alfred Bryan, a busy man in the music business at that time. There were no big hits, but man of their songs were respectable sellers, as indicated by the volume of remaining copies. For reasons that are unclear, their composing relationship appears to have ended in 1909, as no Mills/Bryan songs are found in later years.Some time before 1910, the Mills family moved across the Hudson to Montclair, New Jersey, meaning he was now commuting to work in Manhattan, unusual since a vast majority of composers and most publishers chose to live in Manhattan, Brooklyn, or another close by borough. Frederick was shown living in Montclair in the 1910 census as F.A. Mills, still unmarried, as a publisher of music, with Annie, Florence and Caroline. While his output that year was fairly decent for both himself and his publishing catalog, there were no long lasting hits like those of his past and business started to decline. In 1911 Mills enjoyed a minor surge with The Rag Time College Girl, which was one of several songs he had contributed to the stage musical The Fascinating Widow starring female impersonator Julian Eltinge. A reboot of an earlier version by Otto Hauerbach, it ran for 56 performances on Broadway.

Perhaps dispirited, or overwhelmed by the business end of his firm, Frederick's own compositional output ceased in 1912 and 1913. In his role as publisher Mills became more involved with important business affairs for a time. However, he nearly made a misstep along the way. The short version of the story is that composer Lewis F. Muir had encountered sometime-lyricist and writer L. Wolfe Gilbert on the street in New York. After a brief exchange between them, with Muir criticizing Gilbert's critiques, they challenged each other to come up with a song. That evening, or thereabouts, they came up with two; a ballad and a "Dixie" song. Then the two independently took their collaborations out to publishers. Gilbert reportedly ended up in the office of F.A. Mills Publishing, and as the legend goes, in Frederick's office. After demonstrating the numbers Mills expressed some interest in the ballad. However, he told Gilbert that the Dixie song would not pass muster, as such songs were by now old hat. An indignant Gilbert left the office, but forgot to take his copies with him. When Gilbert later returned to retrieve the manuscripts, Mills admitted that he had not been able to get that tune out of his head, and agreed to give it a run. Within weeks, several of Broadway's top performers were singing Waiting for the Robert E. Lee, which a century and more later remains an often performed example of the best of the ragtime era.

However, he nearly made a misstep along the way. The short version of the story is that composer Lewis F. Muir had encountered sometime-lyricist and writer L. Wolfe Gilbert on the street in New York. After a brief exchange between them, with Muir criticizing Gilbert's critiques, they challenged each other to come up with a song. That evening, or thereabouts, they came up with two; a ballad and a "Dixie" song. Then the two independently took their collaborations out to publishers. Gilbert reportedly ended up in the office of F.A. Mills Publishing, and as the legend goes, in Frederick's office. After demonstrating the numbers Mills expressed some interest in the ballad. However, he told Gilbert that the Dixie song would not pass muster, as such songs were by now old hat. An indignant Gilbert left the office, but forgot to take his copies with him. When Gilbert later returned to retrieve the manuscripts, Mills admitted that he had not been able to get that tune out of his head, and agreed to give it a run. Within weeks, several of Broadway's top performers were singing Waiting for the Robert E. Lee, which a century and more later remains an often performed example of the best of the ragtime era.

However, he nearly made a misstep along the way. The short version of the story is that composer Lewis F. Muir had encountered sometime-lyricist and writer L. Wolfe Gilbert on the street in New York. After a brief exchange between them, with Muir criticizing Gilbert's critiques, they challenged each other to come up with a song. That evening, or thereabouts, they came up with two; a ballad and a "Dixie" song. Then the two independently took their collaborations out to publishers. Gilbert reportedly ended up in the office of F.A. Mills Publishing, and as the legend goes, in Frederick's office. After demonstrating the numbers Mills expressed some interest in the ballad. However, he told Gilbert that the Dixie song would not pass muster, as such songs were by now old hat. An indignant Gilbert left the office, but forgot to take his copies with him. When Gilbert later returned to retrieve the manuscripts, Mills admitted that he had not been able to get that tune out of his head, and agreed to give it a run. Within weeks, several of Broadway's top performers were singing Waiting for the Robert E. Lee, which a century and more later remains an often performed example of the best of the ragtime era.

However, he nearly made a misstep along the way. The short version of the story is that composer Lewis F. Muir had encountered sometime-lyricist and writer L. Wolfe Gilbert on the street in New York. After a brief exchange between them, with Muir criticizing Gilbert's critiques, they challenged each other to come up with a song. That evening, or thereabouts, they came up with two; a ballad and a "Dixie" song. Then the two independently took their collaborations out to publishers. Gilbert reportedly ended up in the office of F.A. Mills Publishing, and as the legend goes, in Frederick's office. After demonstrating the numbers Mills expressed some interest in the ballad. However, he told Gilbert that the Dixie song would not pass muster, as such songs were by now old hat. An indignant Gilbert left the office, but forgot to take his copies with him. When Gilbert later returned to retrieve the manuscripts, Mills admitted that he had not been able to get that tune out of his head, and agreed to give it a run. Within weeks, several of Broadway's top performers were singing Waiting for the Robert E. Lee, which a century and more later remains an often performed example of the best of the ragtime era.Near the end of 1912 he and the firm of M. Witmark & Sons filed a joint action against Standard Music Rolls, arguing that their practice of including lyric sheets with song rolls was a violation of the 1909 Mechanical Music Rights law. They won a temporary injunction against Standard in January 1913, in spite of the argument that the lack of lyric sheets made the rolls a less viable commodity for customers. In short order, the practice of stamping lyrics on the rolls was adopted. Since Standard had already stopped distributing the lyric sheets as soon as the suit was filed, the final verdict, rendered in July 1915, awarded the plaintiff of six cents, described as compensation for nominal damages.

In short order, the practice of stamping lyrics on the rolls was adopted. Since Standard had already stopped distributing the lyric sheets as soon as the suit was filed, the final verdict, rendered in July 1915, awarded the plaintiff of six cents, described as compensation for nominal damages.

In short order, the practice of stamping lyrics on the rolls was adopted. Since Standard had already stopped distributing the lyric sheets as soon as the suit was filed, the final verdict, rendered in July 1915, awarded the plaintiff of six cents, described as compensation for nominal damages.

In short order, the practice of stamping lyrics on the rolls was adopted. Since Standard had already stopped distributing the lyric sheets as soon as the suit was filed, the final verdict, rendered in July 1915, awarded the plaintiff of six cents, described as compensation for nominal damages.In the meantime in 1914 Mills had once again returned to the form that had worked so well for him, bringing out Kerry Mills Turkey Trot and Kerry Mills Fox Trot to capitalize on these two latest dance crazes. It appears, based on subsequent records, that Frederick was married around 1914 as well to Theresa Marion Leavey. Late in 1914 Mills was contemplating a move to 47th Street near Times Square where many other publishing firms had opened offices or relocated. Not helping issues was the failure of a Gilbert tune, Buy a Bale of Cotton for Me, for which Mills had gratefully accepted a loan of $20,000 from George Cohan to help pay for promotion of the tune. The promotion was not enough for a mediocre song, and as Mills put it, "Cotton went down to the lowest level in history. The boll weevil won by a knockout." Even though Cohan tore up the note promising payback of the debt, other deep issues were looming on the horizon which would impede Frederick's forward progress.

Around this time and into 1915, the Cakewalk enjoyed a brief twenty year anniversary revival, which gave a further boost to some of the early Mills works. However, it was not enough to stave off recent problems with the diminishing and aging catalog. The end result was reported in the Music Trade Review of July 3, 1915 as follows:

Fred (Kerry) Mills, doing business as a music publisher under the title of F. A. Mills, Inc., was petitioned into bankruptcy last week by Daniel F. Clancy, Alfred Anderson and Maxwell Silver, it being alleged that preferential payments had been made to certain creditors. No definite statement regarding the assets or liabilities of the concern have been made public. It is declared that an effort will be made to free the business from difficulties and continue it... The present difficulty is attributed to general business depression and a lack of really successful numbers.

By August Mills had "filed schedules in bankruptcy, with liabilities of $62,293 and assets of $1,724." The assets, including "pianos, piano stools, desks, filing cabinets, and the usual office equipment material," were ultimately sold off at auction on November 12, 1915. In the meantime, his son, Frederick Allen, Jr., had been born in September.

Frederick's troubles continued even after the bankruptcy filing. One example was notice in 1916 stating that: "Daniel L. McCarthy, of New York, has sued Frederick A. Mills, music publisher, in the Circuit Court to recover on a promissory note for $10,000. The note, it is declared, was given by Mr. Mills to Geo. M. Cohan, the actor and playwright, who assigned it to McCarthy." Similar suits for smaller amounts were also filed. Now largely insolvent, Mills ended up selling much of his catalog to other publishers. His pieces were initially bought by the clearing house of Maurice Richmond of the Richmond Music Company for a bit over $3,000, later to be sold to and republished by houses as diverse as Walter Jacobs, Oliver Ditson, Paull Pioneer and Jack Mills, with many of the copyrights bought up by Jerry Vogel from the 1930s to 1950s. He also had to part with his large colonial home in Montclair in September of 1916.

The note, it is declared, was given by Mr. Mills to Geo. M. Cohan, the actor and playwright, who assigned it to McCarthy." Similar suits for smaller amounts were also filed. Now largely insolvent, Mills ended up selling much of his catalog to other publishers. His pieces were initially bought by the clearing house of Maurice Richmond of the Richmond Music Company for a bit over $3,000, later to be sold to and republished by houses as diverse as Walter Jacobs, Oliver Ditson, Paull Pioneer and Jack Mills, with many of the copyrights bought up by Jerry Vogel from the 1930s to 1950s. He also had to part with his large colonial home in Montclair in September of 1916.

The note, it is declared, was given by Mr. Mills to Geo. M. Cohan, the actor and playwright, who assigned it to McCarthy." Similar suits for smaller amounts were also filed. Now largely insolvent, Mills ended up selling much of his catalog to other publishers. His pieces were initially bought by the clearing house of Maurice Richmond of the Richmond Music Company for a bit over $3,000, later to be sold to and republished by houses as diverse as Walter Jacobs, Oliver Ditson, Paull Pioneer and Jack Mills, with many of the copyrights bought up by Jerry Vogel from the 1930s to 1950s. He also had to part with his large colonial home in Montclair in September of 1916.

The note, it is declared, was given by Mr. Mills to Geo. M. Cohan, the actor and playwright, who assigned it to McCarthy." Similar suits for smaller amounts were also filed. Now largely insolvent, Mills ended up selling much of his catalog to other publishers. His pieces were initially bought by the clearing house of Maurice Richmond of the Richmond Music Company for a bit over $3,000, later to be sold to and republished by houses as diverse as Walter Jacobs, Oliver Ditson, Paull Pioneer and Jack Mills, with many of the copyrights bought up by Jerry Vogel from the 1930s to 1950s. He also had to part with his large colonial home in Montclair in September of 1916.In spite of this disheartening loss, Mills still attempted to put something on the market in 1915 and 1916. The Owl's Cotillion was self-published in Montclair on his Music Craftmasters label, the only entry that appears to have been released under that moniker with his name, although three other titles were registered that same year as Frederick Mills. There were at least seven other pieces copyrighted under Music Craftmasters, all of them using pseudonyms, including Why Do We Love the Baby's Hands? as Pierre Morin, likely written to honor the birth of his son. It is probable that Mills used pseudonyms to both disassociate these works from his early ragtime material, and to hide, at least publicly, from issues dealing with his current bankruptcy and financial troubles. His name did not appear on the initial copyrights, but he was revealed as the composer when he re-copyrighted these works in 1943. The firm was shown as located in Grand View, New York, a part of Nyack, about thirty miles northeast of Montclair. Of some interest is My Sweetest Day, composed as Avery St. Clair, with a rare set of lyrics by sheet music cover artist Andre C. de Takacs, who had also done a few of the Music Craftmasters covers. At least some of these works were on the market, but apparently only for one printing.

Frederick formed a new publishing firm in 1918. As announced in The Music Trade Review of August 17, 1918: "F. A. Mills, who several years ago was prominent among the popular publishers, has again entered the field. His new firm is incorporated under the name of Kerry Mills, Inc., Kerry being the name by which he is best known." It initially brought out one song for the war effort, and the throwback piece Snooky Hollow. Subsequent years saw an output of one piece a year from the aging composer, who appears to have finally put his pen down in 1922. The 1920 census failed to turn up Frederick, but Theresa and Frederick, Jr., were residing with her parents in Manhattan, indicating a probable separation. She showed as married, perhaps eschewing a divorce, most likely being an Irish Catholic like her Irish immigrant parents. This status continued until his death, although in the 1930 and 1940 enumerations Theresa declared herself as widowed.

His new firm is incorporated under the name of Kerry Mills, Inc., Kerry being the name by which he is best known." It initially brought out one song for the war effort, and the throwback piece Snooky Hollow. Subsequent years saw an output of one piece a year from the aging composer, who appears to have finally put his pen down in 1922. The 1920 census failed to turn up Frederick, but Theresa and Frederick, Jr., were residing with her parents in Manhattan, indicating a probable separation. She showed as married, perhaps eschewing a divorce, most likely being an Irish Catholic like her Irish immigrant parents. This status continued until his death, although in the 1930 and 1940 enumerations Theresa declared herself as widowed.

His new firm is incorporated under the name of Kerry Mills, Inc., Kerry being the name by which he is best known." It initially brought out one song for the war effort, and the throwback piece Snooky Hollow. Subsequent years saw an output of one piece a year from the aging composer, who appears to have finally put his pen down in 1922. The 1920 census failed to turn up Frederick, but Theresa and Frederick, Jr., were residing with her parents in Manhattan, indicating a probable separation. She showed as married, perhaps eschewing a divorce, most likely being an Irish Catholic like her Irish immigrant parents. This status continued until his death, although in the 1930 and 1940 enumerations Theresa declared herself as widowed.

His new firm is incorporated under the name of Kerry Mills, Inc., Kerry being the name by which he is best known." It initially brought out one song for the war effort, and the throwback piece Snooky Hollow. Subsequent years saw an output of one piece a year from the aging composer, who appears to have finally put his pen down in 1922. The 1920 census failed to turn up Frederick, but Theresa and Frederick, Jr., were residing with her parents in Manhattan, indicating a probable separation. She showed as married, perhaps eschewing a divorce, most likely being an Irish Catholic like her Irish immigrant parents. This status continued until his death, although in the 1930 and 1940 enumerations Theresa declared herself as widowed.At some point in the mid-1920s, Frederick left the east coast for California. He appears there as still married yet living alone in the 1930 census, and listed as a writer. Efforts to find samples of his writing in his last two decades came up rather nebulous, with no confirmable information. It may have been for a magazine or newspaper, and not published books. However, given his location in the early 1930s in Hollywood, variously on Normandie Avenue until 1934 and Melrose Ave through the late 1930s, he was most likely writing or editing for the film industry, or even in radio. As Mills had copyrighted some musical works under pseudonyms in prior years, it is possible that he could have done so while he was writing. He gained admission into ASCAP in 1932.

Frederick spent his final years alone in Los Angeles. By the time of the 1940 enumeration Frederick had moved from Hollywood, and again claimed only to be a writer. Across the country in the Bronx, New York, Theresa, showing as widowed, and Frederick, Jr., were still residing with her Leavey siblings. From around 1939 to 1948, the former composer and publisher, who frequently heard At a Georgia Campmeeting incorporated into various Hollywood films, lived in Hawthorne, just off Imperial Highway, next to the current southeast corner of Los Angeles International Airport.

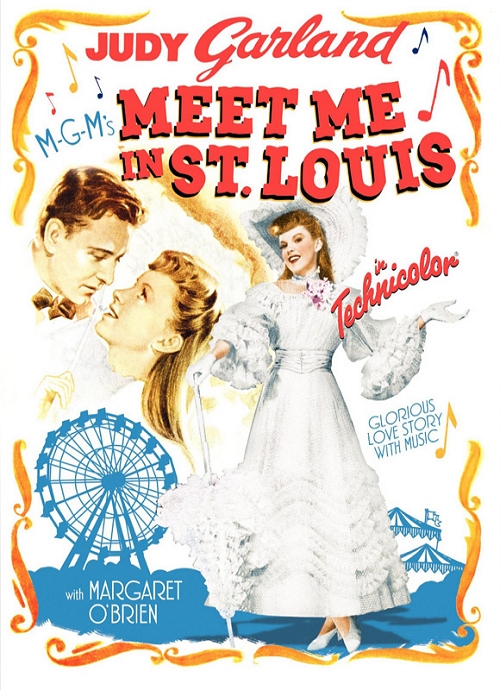

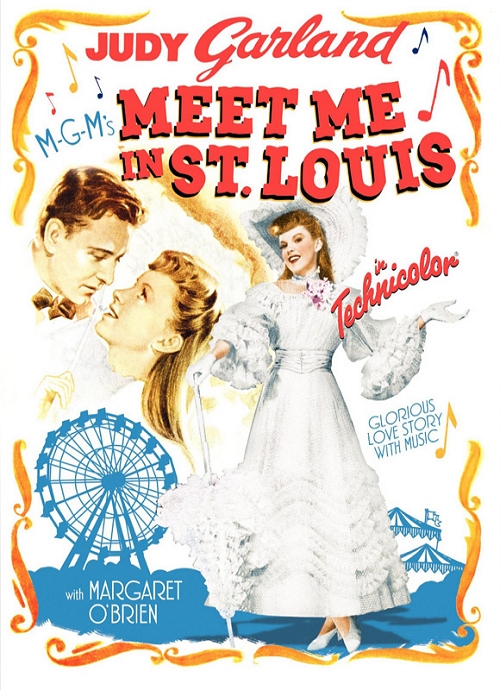

Mills had one final moment of fame in 1944 when his famous song, Meet Me In St. Louis, was used as the title and theme for a Vincent Minnelli film produced by MGM, and starring Judy Garland. Copies of a couple of his works in this ragtime-rich film can be seen on the piano in some scenes. Mills shows up in California voter rolls, usually as a writer, in 1942, 1944, 1946 and 1948, passing on as a result of throat cancer in near obscurity in December of 1948. Fortunately his music has remained anything but through continuing popularity of St. Louis, Red Wing, the Georgia Campmeeting, and many more examples from the white composer who successfully helped to popularize black music at the beginning of the ragtime era.

A few pieces of information on the composer were derived from a 1999 Rag Times article on Mills written by historian Richard Zimmerman. Thanks go to John Paul Biersach who has helped uncover some additional Mills compositions not readily found by researchers writing on him. He also generously provided confirmations and some additional information on Mills that enhanced this essay. Also, Dr. Edward Berlin for information regarding Mills' claims concerning his early position at the University of Michigan.