This is a story of two different Frank Bantas, father and son. Although their careers were separated by a number of years for unfortunate reasons, they were also remarkably intertwined, and both filled with a measure of success and names familiar to and associated with both of the Bantas. The histories of either Banta have rarely been told, yet both of them had a rich legacy in the early dissemination of recorded ragtime and popular music in the United States and around the world. Some portions of their collective stories are being told here for the first time in decades, or even a century.

Frank P. Banta

The elder Frank Banta was the fourth of five children born in New York City to John William Banta and Frances Green "Fannie" Darrow, the others being Elizabeth C. (9/6/1865-7/28/1866), George A. (12/16/1866-4/28/1870), John W., Jr. (1/2/1869) and Catherine J. "Katie" (12/27/1879). The 1870 and 1880 enumerations both showed John to be a wood carver, although other specifics were not found as to a particular market, such as furniture design or building decoration. Virtually nothing has been reported on Frank's training, but given his early repertoire, it is clear that he learned harmony, theory, sight reading, and works by at least some of the well-known classical composers. In the early 1890s he started making his way as a pianist, and it appeared he was working with some moderately well-known vaudeville folks by 1892, many of them who would become essential as recording artists. A Huntington Long Islander [Long Island, New York] article from October 22, 1892, noted his appearance in a "first class variety entertainment" held at the local opera house, with a number of artists from theatrical entrepreneur Tony Pastor's company in attendance. Suggesting a number of possible connotations concerning either his advanced music education or his status with the group, Frank was mentioned in the article as "Prof. Frank P. Banta."

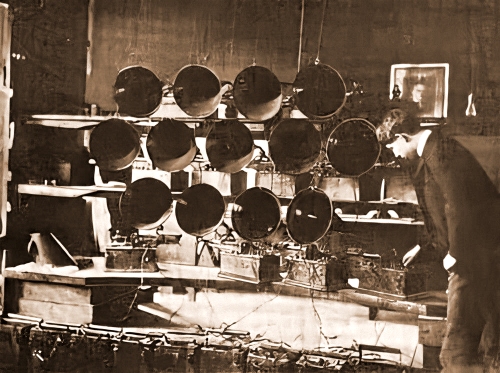

When Thomas Edison first invented what would become known as the phonograph, his intention was that it would be an ideal instrument for dictation and the capture of oration. Similar inventors, including Alexander Graham Bell,

saw it as a means for capturing telephone conversations or even telegraphy. Edison eschewed the idea that his invention should be used for the reproduction of music. However, other inventors sought to improve the acoustical capture and playback properties of phonographs, and by the mid-1890s both Berliner flat discs and Columbia cylinders were being sold to the public with the idea that they could bring great performances into their homes. Both formats had inherent flaws. Cylinders retained a constant speed for either two or four minutes (depending on how the machine was geared), but until around 1902 or so could not be produced in mass, requiring performers to cut ten or so at a time in a day-long session of dozens of performances of the same piece. Those in turn could be copied via a tube to more cylinders, but with a significant loss in fidelity. As for the Berliner-style records, as the needle got closer to the center of the disc the rate of speed through the groove was significantly reduced, changing the fidelity. However, they were easy to reproduce from a single master, allowing for tens of thousands of copies of a single performance. Both, however, were not all that friendly to instruments like the guitar, double bass, or piano, as early recording horns and studio techniques simply could not capture the full breadth or nuances of these instruments.

|

When record companies started looking for material for the public to take home with them, vocalists were at the top of the list, often with a small but loud ensemble, including studio bands assembled for that very purpose. However, for instrumental pieces of popular songs, the banjo had a clear advantage over other instruments in the late 1890s, as it was not only easy to capture by most recording horns, but would carry further on the average playback horn as well.

This property, a knowledge of current popular works, and a name that the public knew, made banjoists like Vess Ossman and his peers valuable commodities in the mid-to-late 1890s. A little late to the game, Edison started issuing music discs in 1896. Although Edison himself was not a big proponent of popular music, he eventually put others in charge of the recording end of his enterprise, stipulating that fine classical works would always be available on his label.

|

He still managed to get some recording dates, possibly as early as 1893, and definitely by the mid-1890s. Frank soon became known as a versatile and capable accompanist. Actually, as the ragtime style of piano playing was still in its infancy, and the poor reputation of the piano on discs, much less the rigors of the recording sessions, were well known to many, there was not all that much competition in the late 1890s in the field of studio pianists. Most of Banta's recorded work was done accompanying singers or banjo players, with very scant solo appearances, due to the difficulties caused by early recording horns and diaphragms. While Frank would record several cylinders for Edison and a handful of discs for Victor over the next few years, the bulk of them would be cut from June of 1902 into late 1903, once the methodology had been perfected for mass reproduction of cylinders. The necessity of playing the same piece fifty times in a day to reproduce 500 cylinders was simply not a appealing option for any soloist, ensemble or vocalist. Given the tone of the piano, the reproduction in the inner grooves of a flat disc were even more of a problem than for many other instruments or certain timbres of voices. As a result, banjos and tenors were among the most recorded subjects of the time, but at that, piano accompaniment was still often desired, which was good business for versatile performers like Frank.

As a result, banjos and tenors were among the most recorded subjects of the time, but at that, piano accompaniment was still often desired, which was good business for versatile performers like Frank.

As a result, banjos and tenors were among the most recorded subjects of the time, but at that, piano accompaniment was still often desired, which was good business for versatile performers like Frank.

As a result, banjos and tenors were among the most recorded subjects of the time, but at that, piano accompaniment was still often desired, which was good business for versatile performers like Frank.Recording logs and practices into the late 1890s were often lax in identifying personnel on recordings. Therefore, even though there are likely many more recordings featuring Frank P. Banta at the piano than those listed here and in other traditional sources, some of them will never be known for sure. He certainly accompanied a great many Edison artists in the 1890s, including their shining star, banjoist Vess Ossman. He also played some cuts in the early part of the 1900s with another banjoist a few years younger than himself, Fred Van Eps. Fred would play an important role in the Banta legacy within a few years. For the most part, however, Frank's work with many of the start singers of Edison's company, as well as some early cuts for the Consolidated Record Company of 1900 that would become the more famous Victor Records by 1901, was better known throughout the music industry. One of those was the current hit Hello Ma Baby, which is unusual in that it was essentially a ragtime piano solo, one of the few from the early part of the ragtime era.

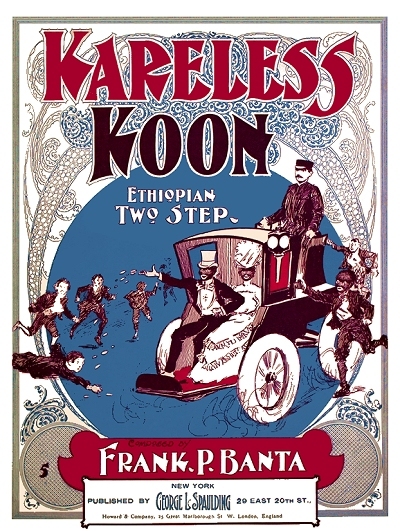

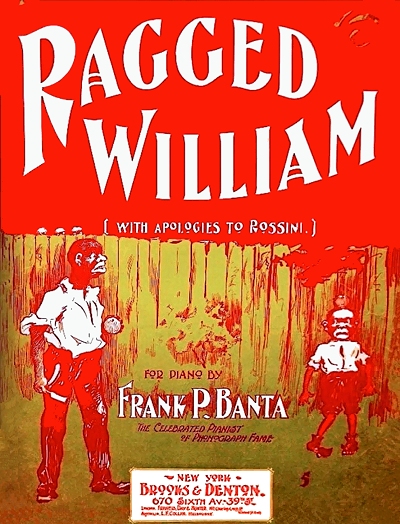

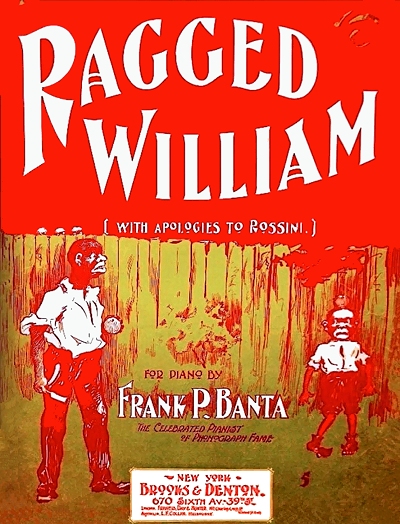

In addition to his recording a performing work, Frank dabbled in composing starting in the mid-1890s with a pair of bicycle-themed pieces at a time when so-called safety bicycles with chain drives and equally-sized wheels were exploding in popularity. In 1899 he turned out his two most representative works. Ragged William was a predictive instrumental, being a mildly syncopated parody on a known classical piece, a reduction of the famed William Tell Overture by Gioachino Rossini. Such parodies would be increasingly popular over the next decade. Kareless Koon was a fine cakewalk that bordered on ragtime, but never quite crossed that line, having a lot of syncopation, but none of it across the barlines. The Town Pump from 1902 was a fine march, but overshadowed by a glut of marches on the market at that time, including a great many from Sousa and the E.T. Paull company. None of his works were great sellers, but just the same, some of his pieces would be recorded by other artists of the period.

In mid-1902, with a new molding process in place that allowed for reliable mass-duplication of cylinders based off one master, the Edison Company launched into a flurry of recording activity. Whereas in the past only one or two pieces could be captured in a day, albeit 25 to 50 times, the new process allowed the musicians to do between one and three takes, then move on to another piece. Instead of an artist being responsible for perhaps three to five titles in a month, it was now possible to do as many as twenty. In order to build up their inventory, the Edison recording laboratory went into overdrive, keeping Frank gainfully employed for much of the next year and longer. He was also mentioned for many live performances in a positive light, including the New Rochelle [New York] Pioneer of October 18, 1902:

the new process allowed the musicians to do between one and three takes, then move on to another piece. Instead of an artist being responsible for perhaps three to five titles in a month, it was now possible to do as many as twenty. In order to build up their inventory, the Edison recording laboratory went into overdrive, keeping Frank gainfully employed for much of the next year and longer. He was also mentioned for many live performances in a positive light, including the New Rochelle [New York] Pioneer of October 18, 1902:

the new process allowed the musicians to do between one and three takes, then move on to another piece. Instead of an artist being responsible for perhaps three to five titles in a month, it was now possible to do as many as twenty. In order to build up their inventory, the Edison recording laboratory went into overdrive, keeping Frank gainfully employed for much of the next year and longer. He was also mentioned for many live performances in a positive light, including the New Rochelle [New York] Pioneer of October 18, 1902:

the new process allowed the musicians to do between one and three takes, then move on to another piece. Instead of an artist being responsible for perhaps three to five titles in a month, it was now possible to do as many as twenty. In order to build up their inventory, the Edison recording laboratory went into overdrive, keeping Frank gainfully employed for much of the next year and longer. He was also mentioned for many live performances in a positive light, including the New Rochelle [New York] Pioneer of October 18, 1902:The fifth annual banjo concert by the New Rochelle Banjo Club, in Y.M.C.A. Hall, on Wednesday evening, was very creditably given and thoroughly enjoyed by an audience of two hundred people. Professor H.S. Six prepared an excellent program of vocal and instrumental music and recitations... Frank P. Banta proved himself a very skillful pianist and his performance as accompanist in a large measure served to make easy the work of the soloists and to complete the ensemble music.

At a time when there were different recording and playback systems, mainly cylinder and variants on disc, many artists recorded for multiple studios in non-competing formats, in part because the concept of exclusivity and recording contracts were still a few years off. That being said, the majority of credited work for Frank P. Banta was recorded on Edison cylinders, with a few Victor discs, and those largely, at least in theory according to some historians, with Ossman in late 1903. A lot of the material was fluff, but a few of pieces, like Bill Bailey, Won't You Please Come Home, were genuine hits, as was almost anything sung by the dynamic Billy Murray. Frank was on track to be perhaps the most-recorded pianist capable of competently playing ragtime and popular music styles during the first decade of the twentieth century, and was often promoted as a rag-time pianist in print advertisements for recordings and live performances. He was even engaged to play for Prince Henry of England during a visit to the United States after he expressed a desire to hear some rag-time music. Among the pieces Frank played during his command performance at the University Club was his own clever William Tell sendup in rag. With that type of publicity, Banta was gaining credibility as one of the better white performers of the new musical style. However, a potential long-term career in performance was not to be - at least for the elder Frank Banta.

Frank E. Banta - Early Years

Frank P. Banta had been married in Manhattan, New York, on December 4, 1895, to Elizabeth V. "Lizzie" Riley. His only son, Frank Edgar Banta, was born nearly ten months later on September 28, 1896. Traditional sources have shown an 1897 birth year, but two draft registrations for 1918 and 1942, most census records, and official New York City birth records insist on 1896 as the actual year of birth.

This is curiously at odds with the 1900 census, which showed 1897, but given other solid evidence, that entry was likely an anomaly or a calculation error on the part of the enumerator. Similarly, references to him as "Frank Banta, Jr." are also incorrect, given that he did not share his father's middle name. The 1900 enumeration listed Frank P. Banta as a musician as expected. Also in the household was Mary Dougherty, age 55, who was listed as a domestic. Later records would show her as Elizabeth's aunt, so whether she played both roles is unclear, but she was likely a relation who was lending a helping hand. Mary would eventually stay with the Banta family into the 1920s. Frank E. was followed by one sister, Prudence C. (4/18/1901).

|

It is probable that the younger Frank was influenced at a very early age by listening to his dad practice or perform, and also likely from collected records or cylinders of singers and even Vess Ossman as accompanied by Frank P. that were inevitably found in the Banta home. Associations with the artists that the father played with both on record and on stage also rubbed off on the son, perhaps even through visits to the home for get-togethers. It is uncertain how young Frank E. was when he started playing, or even emulating his father at the keyboard, but with a piano in the home it was probably by the time he was five or six. In a June 13, 1960, interview published in the October, 1960, issue of Record Research #30, Banta clearly recalled quite a bit about his musical father:

He wrote songs with JESS DANDY and was an early associate of the WITMARKS music publishing house. If they wanted to steal an unpublished song from a musical show or revue on Broadway, they would buy a pair of tickets for him and mother. He would copy down the melody on manuscript paper as the performer sang it, and submit same to publisher. In those days it was piracy. Today it's payola.

Father was of slight stature and had a subtle sense of humor. Great natural talent. Composed, arranged and directed orchestra. He wrote a piece called "Halimar," an oriental rondo which was quite popular in the '90s. Also a lancers which was danced as they do the La Raspa today called Children's Games...

After his sister Prudy was born, it looked like the Bantas would be living the ragtime life in style. Then it suddenly stopped. As of September of 1903, Frank had started suffering from chronic interstitial nephritis for the next two months, potentially from an auto-immune issue or ingested toxin, in addition to at least a decade of asthma. The combination ultimately took the life of Frank P. Banta on November 30, 1903, at age 33½. The announcement in the New York Herald only noted that there would a funeral at the Church of Saint Ignatius Loyola on 84th Street on December 2, where a requiem mass would be celebrated, something reserved for parishioners of at least some standing in the church. Members of the Musical Mutual Protective Union, as well as the Aschenbroedel Verein, a Germanic professional orchestral musicians social and benevolent association established in New York City, were openly invited to pay their respects. This was followed by a burial at Trinity Cemetery. As for the Edison company and Banta's recorded legacy, it may have seemed a little eerie to some, but business was business, and Frank's last ten or so cylinders were released posthumously over the next several weeks.

The 1905 New York census showed the widowed Elizabeth living alone in Manhattan with her two children, but no occupation or means of support was listed. She may have been helped along in those first years by the decent amount that Frank had earned from recording and performance dates, and organizations such as those invited to the funeral also tended to help surviving families of the members for at least a short while. At some point over the next couple of years Elizabeth's aunt Mary Dougherty took up permanent residence with the family. The 1910 census showed Elizabeth working as a saleslady in a corset house, and there were two lodgers in the home to help defray expenses. The Bantas lived at 1286 Lexington Avenue near East 86th Street in the Yorkville neighborhood on the upper east side of Manhattan, not far from Gracie Mansion, the mayoral residence. As per his 1960 interview, Frank recalled his early formal musical training:

The Bantas lived at 1286 Lexington Avenue near East 86th Street in the Yorkville neighborhood on the upper east side of Manhattan, not far from Gracie Mansion, the mayoral residence. As per his 1960 interview, Frank recalled his early formal musical training:

The Bantas lived at 1286 Lexington Avenue near East 86th Street in the Yorkville neighborhood on the upper east side of Manhattan, not far from Gracie Mansion, the mayoral residence. As per his 1960 interview, Frank recalled his early formal musical training:

The Bantas lived at 1286 Lexington Avenue near East 86th Street in the Yorkville neighborhood on the upper east side of Manhattan, not far from Gracie Mansion, the mayoral residence. As per his 1960 interview, Frank recalled his early formal musical training:I studied under a local [Yorkville] piano teacher named Frank Hauser from nine years of age to about fifteen. Hearing PAUL WHITEMAN's orchestra for the first time provided a real thrill... [As Whiteman and his orchestra were not playing on the East Coast until 1920, this is a curious juxtaposition.]

My first job was a wedding I played at age of about fourteen with a fiddler for one dollar each. They were friends of the family and we worked about seven or eight hours. The next year I played in dancing school for weekly dances with a five-piece orchestra on 86th Street near Third Avenue. The side men got. two dollars each. I was the leader and got paid two fifty.

My next inspiration was FELIX ARNDT. I replaced him with FRED VAN EPS (Banjo Orchestra and Trio) at age seventeen playing dance dates and recording at age eighteen with [the] VAN EPS TRIO on Victor. This was "On the Dixie Highway"... backed by "Teasing the Cat." The trio consisted of banjo, saxophone and piano. Van Eps was among the first to recognize the saxophone as a "new sound". He would write obbligato in style of cello part as there were no sax parts published around 1914-1918... For five or six years the extra pianist working for FRED VAN EPS was none other than GEORGE GERSHWIN. [It was actually closer to three years.] Imagine that great talent being my stand-in!

It was due to some kind of physical or mental deterioration on the part of the otherwise highly-talented Felix Arndt, composer of the iconic early piano novelty Nola named for his future wife Nola Locke, that made it difficult for him to perform reliably on recordings with Van Eps. Arndt continued to arrange piano rolls brilliantly and to compose until his death from the Spanish Flu pandemic in late 1918. However, Van Eps needed somebody of a similar caliber to provide a solid but interesting foundation for his banjo playing. Fred had actually known and briefly played with the elder Banta in 1902 and 1903 for a couple of live appearances, and possibly worked with him on a recording session covering some of Vess Ossman's work. Even more than a decade later the reputation of Frank P. Banta had some gravitas, so it was not too much of a stretch for Fred to take on the younger Frank Banta as an accompanist, and even as a musical apprentice.

Improvements in horn and diaphragm technologies, as well as disc materials, had made recording of the piano more viable by 1916 when Frank started recording, so there were more opportunities for his playing to be heard and to stand out. Having originally worked his brother Bill on banjo, Van Eps was more or less cajoled into employing Victor staff drummer Eddie King to replace the second banjo. When Banta first joined him on the Pathé recordings, Fred had brought in saxophonist Nathan Glantz as the third member of the trio, a combination he much preferred. Victor caught on that the Pathé discs were well received, and relented, giving the increasingly popular Van Eps a great deal of say on what and how he recorded. By the end of 1917, having made recordings on Columbia, Pathé, Emerson and Victor, the Van Eps trio were clearly as popular other period stars, including Nora Bayes, Al Jolson, the Peerless Quartet, and Billy Murray, having clearly eclipsed the reputation of Vess Ossman by this time. Banta had also been worked with drummer Howard Kopp on some important solo ragtime tracks, his first Columbia records, which included Nat Johnson's Calico Rag. He had worked with a couple of other artists on Columbia and Pathé as well. However, Van Eps, as well as Victor, had their own plans for the pianist, which would clearly put him in the public eye.

The Victor Artists

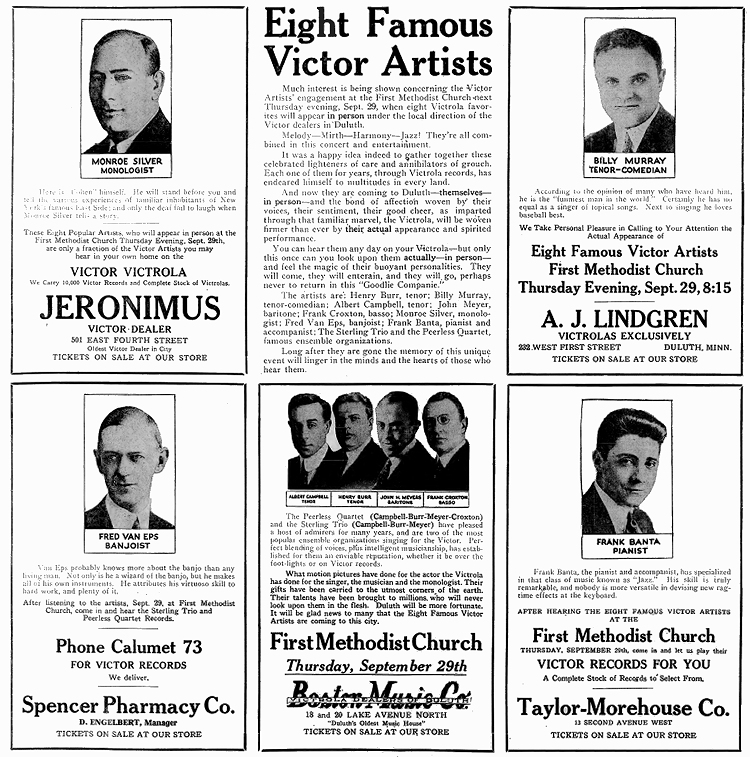

In 1915 singer Henry Burr (Harry H. McClaskey) helped to put together a power group of their top recording artists from the Victor and other record companies, sending them on an annual tour around the United States to present concerts in a variety of venues, all to promote their records. They even played records at some of the presentations to show how clean and clear they were, such demonstrations being common amongst both recording companies and phonograph manufacturers. For the first two seasons of the tour the star banjo attraction was Vess Ossman. However, in 1917, he not only quit recording altogether (according to some sources being either threatened by or tired of being compared to Van Eps), but owing to "creative differences" with the group's leader and manager Burr, quit the group as well. Van Eps was asked to replace Ossman almost immediately in May of 1917, and thus began his run with "The Record Makers" or the "Eight Famous Record Artists," two of the many names given the touring group.

Among the participating artists, of which there only a couple of minor rotations from 1917 through 1922, was manager Henry Burr; Billy Murray, whose popularity on disc rivaled and at times eclipsed that of Al Jolson; singer Albert Campbell (a.k.a. Frank Howard) from the famous Peerless Quartet; singer John H. Meyer, who with Campbell had been a part of the Sterling Trio;

basso singer Frank Croxton, also a part of the Peerless Quartet; Jewish comedian and monologist Monroe Silver; and, at Van Eps insistence, Frank Banta. He replaced composer/pianist Theodore Morse, who was, according to Fred, "a swell fellow and one of the greatest writers of popular songs this country has known, but he simply couldn't play the piano the way Frank Banta could." The group was heavily advertised wherever they went, and their performances well-attended. At prices from .50 cents to $2.00 per seat, they were also affordable and accessible to most of the public. By 1920, when they all had contracts with Victor, they became Victor's "Eight Famous Phonograph Artists." The tours, which included stints in Canada where Van Eps and Banta recorded on HMV, were typically three to four months each spring into the early summer.

|

Differences with the sometimes volatile Burr, some of which had led to Ossman's departure, appeared to be commonplace during the group's history, as the comedy singing team of Arthur Collins and Byron Harlan were among those who also left the troupe due to constant bickering with the leader. But for a time, Van Eps and Banta got along well during their travels, noting that they usually had first-class accommodations wherever they went, and made sure they were always well-dressed. At one point, Fred was accidentally handed a check for the group's take for a performance, and found the number to be at least double what he would have expected, even accounting for Murray being the top-paid artist in the group. He and some of his peers decided to comically strike on the boss, storming upon him with fake beards like anarchists. The joke continued for some time, and they formed their own internal group, the Order of Beards, of which Frank was a charter member.

The January, 1920, census showed Frank continuing to reside with his mother and sister in Manhattan while not on tour, along with his grand aunt Mary Dougherty. In another groundbreaking and somewhat historical move, the Van Eps Trio, with Bill Van Eps on the banjo, was engaged to shoot an eight minute long sound film in 1921 titled A Bit of Jazz. Being one of the early experimental films using the 21 frame-per-second synchronized sound-on-disc Photo-Kinema system developed by Orlando Kellum, it made Frank one of the first jazz pianists to perform in a synchronized-sound film. Due to poor acoustical horn sound recording and a lack of theaters equipped with the necessary equipment to display the film, Kellum's system and the few films shot on it went nowhere, particularly after subsequent electrically-recorded sound-on-film and the Vitaphone sound-on-disc systems took off. This film still exists in a restored 24 fps version at the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

In early 1921, Van Eps went into business with Burr in order to build his own line of custom banjos. After a year or so of great success as banjo manufacturers, Burr and Van Eps began to butt heads concerning their respective roles in the company and the handling of finances. By July of 1922, Fred left the Victor Eight to pursue other leads, including the growing of his banjo business. The official statement to the world through the July, 1922 issue of Talking Machine World was that an increasing level of engagements in New York City kept Fred from touring with the group any longer. He was replaced by saxophonist Rudy Wiedoeft. Frank chose to stay with the Victor Famous Eight until 1928, when they finally disbanded, having served their purpose for more than a decade.

The decision nearly terminated his professional relationship with the mentor who had given him his big break, although they did record a few more tracks into 1923. Still, as the necessary foundation for all of the other artists on the Victor Famous Eight tour, Frank had now developed his own fame, playing for more or less the entire show both as soloist and accompanist. One of his performances was described in the December 10, 1921 issue of the Music Trade Review:

|

ONE of the most impressive sights that the Commentator has ever witnessed is the marvelous terpsichorean display by Frank Banta's swallow coat tails. Banta, introduced by Billy Murray as Mrs. Banta's son Frankie, is the piano-playing member of the Eight Famous Victor Artists, who graced Chicago Orchestra Hall and the trade with their benign presence recently. Banta is the most artistic desecrator that ever lived. His pet stunt is desecrating, syncopating, jazzing or otherwise taking liberties with the big operatic things. While preserving the melody, he can make the Miserere from "II Trovatore" sound like an Irish wake. We have heard him do it. We have not heard him handle Chopin's Funeral March so that it sounded like a bunch of cabaret frequenters shimmying", but we do not doubt that he could do it. Yet, in all fairness to Frank, we must say that his desecrations entertain. He makes genial fun of the classics in a delightful way which makes you suspect that he really loves them; and knows them, too...

Frank Banta's coat tails are becoming classic. Everyone from the humblest member of the trade press to the greatest piano plutocrat or talking machine magnate can obtain entertainment, edification and soul food from the Banta coat tails. Long may they wave!

There is some irony, yet some logic to Banta's recording patterns of the period. Given the three major formats still extant at the time, vertically cut cylinders, vertically cut records, and the more common laterally cut records like Victor and Columbia, there was more a level of necessity by artists to record on each format so they could get their products into the consumer's homes than there was a sense of exclusivity. Contracts were common for publishers, but not as much for record studios at that time. Still, it does stand out that during his many years on the Victor tour that Frank actually recorded more on a variety of non-Victor labels from 1918 to 1924, including Columbia, Emerson, Gennet, Pathé, Brunswick, Banner, HMV, and a few smaller concerns, working primarily as an accompanist for a wide variety of performers in addition to Van Eps. Among them were Harry Akst, pianist for composer Irving Berlin, and composers/pianist Cliff Hess, with whom he would lay down a number of duets both on disc and piano roll. Even before his final recordings with Van Eps in 1923, Frank was a valuable and popular commodity, and even though he rarely recorded alone, he was still quite independent by that time.

Novelties and Ivory Dreams

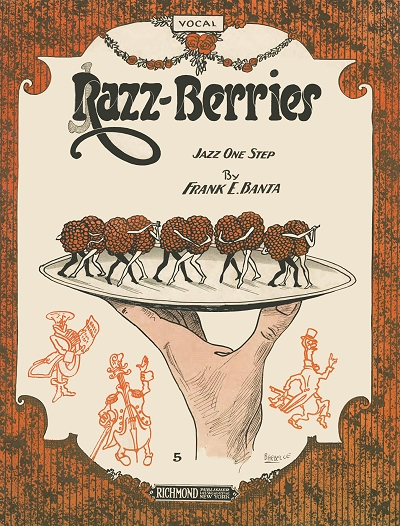

Frank had already dabbled in composing as early as 1917, one of his pieces, Razz-Berries, having been not only published, but recorded by the Van Eps trio. It was popular enough that it was also made into a song, a common practice of the time. Midnight was another minor hit from 1920, but helped to further establish Frank as a composer with some talent. His big break came in 1923 with a novelty cleverly titled Upright and Grand, co-composed with Peter De Rose. Banta later said of De Rose that: "Pete and I were kids together in Yorkville. Another great talent.

He never learned to read music, but how he could compose." Upright and Grand was recorded shortly after its conception by The Ambassadors orchestra with Frank at the piano. It has since become the work for which he is best known. In 1924 he came out with another novelty one-step, in addition to a piano solo titled Prudy, after his younger sister.

|

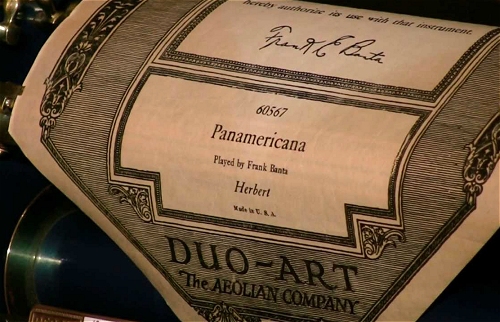

Starting in late 1916, Banta's talent as an arranger as well as performer was applied to the increasingly popular medium of piano rolls. Most of the work he recorded over the next decade was for the Aeolian Piano Company, largely on their expression roll line of Duo-Art releases, many of which were also released without expression on their Melodee [sometimes seen as Mel-O-Dee] line. Frank was engaged for a couple of tours with other Melodee artists in the early 1920s when he wasn't out with the Eight Famous Victor Artists. Among them was Harry Akst and female whiz Edythe Baker. He also cut a few rolls their main competitor, Ampico. A handful of specialty rolls with Banta's name attached to them were released by Wilcox & White, Angelus, De Luxe, and a few smaller brands, some of them being co-opted duplicates of his work for the major labels. It is difficult to get a handle on the total number of rolls for which Frank (or editors he worked with) was responsible between 1917 and 1927, but it was clearly in excess of two hundred fifty. Some of them were also played as four-hand arrangements with a few other pianists.

In early 1925, a time which was the advent of electrically-recorded records, Frank worked primarily for Victor, and was promoted even more heavily during the four remaining tours by the Eight Popular Victor Artists group. One of the first electrical recordings that was commercially released was a 12" disc of the artists in what was titled A Miniature Concert, making it a historic release in terms of both format and content. From this point forward, the piano, and not to long after, thanks to the insistence Edward "Duke" Ellington, the upright bass, would become major components of recorded music.

Banta was now a star in his own right. He was relatively busy working the stage, recording studio dates, piano roll sessions, and the Victor appearances, so did no composing over the next few years.

His 1926 output alone was beyond impressive, many of the records made with various members of the Artists group. In 1928, after the dissolution of the Eight Famous Victor Artists, a group which had served its purpose for 14 years, he went over to the UK and Europe with the Victor group The Revelers as their pianist, playing variety houses and concert halls in London, Paris, Berlin, and points in-between. Europe, France in particular, was hungry for American music at that time, particularly hot jazz and novelty-type piano playing. The trip was such a success and a moneymaker that they returned in 1929. The latter year also saw the last of Banta's novelty compositions, Laurette and Dorothy. As he did not marry until late in his life, it is unclear who either of these women might have been, or if they were just random names chosen as titles.

|

Both the 1925 and 1930 censuses showed Frank living now living north of Manhattan and Harlem in the Bronx area of New York City with his mother, working as a theater musician. Prudence was married in 1926 to Doctor Leslie Suter Blakeman. Radio had discovered Frank Banta in the late 1920s, and by 1930, just as the Great Depression was setting in, there was a clear shift by music lovers with decreasing budgets from buying sheet music and phonograph records to obtaining radio sets instead. The latter was, of course, the least expensive way to keep current, even if the music was not always on demand. Over the next several years, Banta would have a radio presence, but almost none in records. Most piano roll companies had gone out of business by the early 1930s, with QRS one of the few that remained, having bought up the stock of many other concerns. The only Banta rolls from this decade were reissued from early releases. The Revelers with Banta at the piano also made one final trip to Europe in 1931.

In the 1930s Frank became a regular presence on the NBC network, both as a soloist and with other artists. One of the shows he was featured on was the Manhattan Merry-Go Round which originated in New York City from NBC affiliate WEAF. He was also frequently heard on the Mutual Broadcasting System from MBS affiliate WOR. Frank was regularly employed as an accompanist for NBC and MBS singers, usually credited at the end of the program if not before. His most frequent performance partner from around 1930 until nearly the end of the decade, was pianist Milton Rettenberg, although they surprisingly never made records together. He also worked with xylophone player Sam Herman, who had toured in the last years of the Eight Famous Victor Artists, and with saxophonist Rudy Wiedoeft, both artists with whom he had made several Victor records. At one point Frank accurately claimed to be a part of 30 or more broadcasts every week. When not on the air he fronted his own small orchestra for various engagements.

Frank continued to live with his mother, Elizabeth, in Bronx. Tragedy struck the family when Prudence died in 1937 at the age of 36. In the latter part of the 1930s, as scripted shows and swing orchestras started to dominate the airwaves, Frank's name began to appear in the radio listings with less frequency. There were few mentions of Rettenberg during 1937 and 1938, but they did reunite for a series of broadcasts in 1939 with fresh contemporary material. In 1940 Frank was briefly teamed with famed duo pianist Victor Arden (Lewis John Fuiks), who had spent two decades with the likes of pianists Phil Ohman and Adam Carroll on records and piano rolls, as well as on Broadway. However, it was a short union, and soon Frank was mostly on his own. The 1940 census showed him living on University Avenue in Bronx with his mother, listed as a musician in broadcasting.

After 1941 there was little found on Banta. No longer popular on radio, and perhaps simply having chosen to eschew the rigors of broadcasting in an increasingly competitive field, listings for him evaporate during the years of World War II. There are indications in the late 1940s and early 1950s that he migrated to the Novachord, an instrument from the Hammond Organ company that some consider to be the world's first polyphonic synthesizer. As they were only built from 1939 to 1942, it is also possible that he was playing a standard Hammond organ, and that the press applied an incorrect name to his instrument. The 1950 cenumeration showed him living in Bronx, New York, with his mother, listed as a piano player in radio braodcasting. His obituary stated that he became "semi-retired" in 1951. Most of Frank's public performances of the 1950s appear to have been for the Bronx Rotary Club, of which he was a member and the designated pianist.

It has long been thought that Banta was a bachelor. However, he appeared to have married at some point between the late 1940s and mid-1950s, possibly following the death of his mother Elizabeth in 1955, to a woman known only as Cecilia at this time. Around 1962 he and Cecilia relocated from Bronx to Avon by the Sea in Monmouth County, New Jersey. Frank Banta, second generation popular pianist from a family that pioneered in the field of recording and accompaniment, died in Avon by the Sea just days before the end of 1968 at age 72, leaving Cecilia as a widow. He is buried near his parents and sister at the historic Trinity Cemetery on the upper west side of Manhattan.

This article was primarily written from original research by the author through information derived from public records, newspapers, periodicals, and recording logs and lists. There is always room for a little more information, especially for the period of 1942 to 1960, and the identity of Frank's late-in-life wife Cecilia. Fortunately for us, there is a wealth of material still available of both of the Banta's fine playing available in digital format. I can highly recommend for the younger Frank the Rivermont CD release Upright and Grand, consisting of his known solo piano works, and carefully assembled by Rivermont's own Bryan Wright, who is also a fine performer. Many of the Edison recordings of the elder Frank Banta can be found on YouTube in various grades of quality, as can Frank E. Banta's piano rolls. Also, thanks to historian/performer Andrew Greene for helping to pin down some of the Mel-O-Dee roll matrix numbers.

Frank P. Banta Compositions

Frank P. Banta Compositions  Selected Discography for Frank P. Banta

Selected Discography for Frank P. Banta