|

Frank Wooster (February 27, 1885 to June 30, 1942) | |

Compositions and Publications Compositions and Publications | |

|

1905

Universal RagThe Brownie Rag [1] (1905/1907) Black Cat Rag [2] When the Evening Bells are Ringing O'er the Sea [3] Going Back to the Farm [3] That Amuses Me [4] Cynthia: Waltzes [5] 1906

Liza, Won't You Let Me Come In [3]My South Sea Island Queen [3] |

1906 (Cont.)

Clarice: Waltzes [5]When the Moon's Behind the Cloud [6] 1907

The Blue Jay Rag

1. w/Max Wilkins

2. w/Ethyl B. Smith 3. w/Clarence Edmunds 4. w/Ida G. Bierman 5. by McNair Ilgenfritz 6. w/Charles H. Martin |

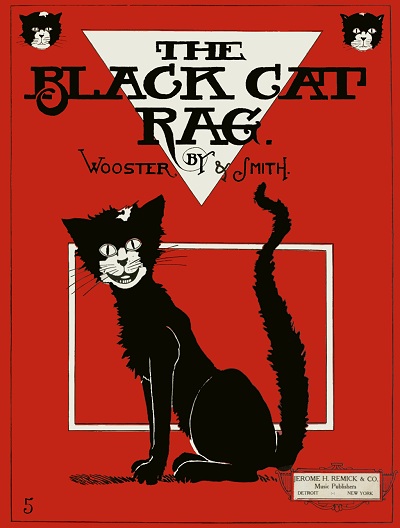

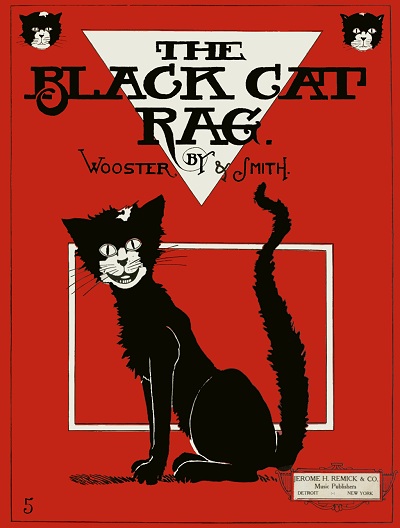

Frank Wooster came to notoriety through a single rag he published with co-composer Ethyl B. Smith, but until this biography was researched, both of them were somewhat of a mystery to the ragtime community, unusual given the popularity of their Black Cat Rag. While the information here is limited, it does tell a story of typical heartbreak met by some who tried very hard to get into the growing music industry, but missed that bubble of success for reasons sometimes difficult to discern, although not for a lack of effort.

Frank was born in St. Louis, Missouri, the only child of Henry Wooster and Josephine Bartholomew. Virtually nothing is known about his musical training or schooling. When Frank was eight years old, his father, a United States Marine, died on December 11, 1893 in the St. Louis U.S. Marine hospital of unspecified causes, leaving Josephine a widow. For the 1900 census, she and Frank were shown living with her parents, former New York residents Vincent and Mary Bartholomew. Vincent was fairly well off and retired, turning 81 that year. The only one in the household with a job was Frank, who was an accounts collector for a local hat store. At some point over the next five years, Frank got the idea in his head that he wanted to go into the music business for himself, and endeavored to do so.

Vincent was fairly well off and retired, turning 81 that year. The only one in the household with a job was Frank, who was an accounts collector for a local hat store. At some point over the next five years, Frank got the idea in his head that he wanted to go into the music business for himself, and endeavored to do so.

Vincent was fairly well off and retired, turning 81 that year. The only one in the household with a job was Frank, who was an accounts collector for a local hat store. At some point over the next five years, Frank got the idea in his head that he wanted to go into the music business for himself, and endeavored to do so.

Vincent was fairly well off and retired, turning 81 that year. The only one in the household with a job was Frank, who was an accounts collector for a local hat store. At some point over the next five years, Frank got the idea in his head that he wanted to go into the music business for himself, and endeavored to do so.The Frank Wooster Co., Music Publishers set up shop in the Commonwealth Trust building at Broadway and Olive streets in 1905 with his first pieces, including Universal Rag and The Brownie Rag. Copying an idea originated by New York publisher Harry Von Tilzer, he put his picture on the cover of most of the pieces with the caption "Frank Wooster - Trade Mark." His 1906 and 1907 listings in the Gould's directory for Saint Louis both show Frank as a music publisher in upper case bold face, so he was serious about it. There are no stories known about rejections from other St. Louis publishers such as Stark and Sons or Thiebes Stierlen, so he may have just wanted to do it by himself, or even for his musical friends.

Among those was another Missouri native, Max Wilkins, with whom he wrote Brownie Rag, and an 18-year-old St. Louis youth named McNair Ilgenfritz who had written a pair of waltzes. Ilgenfritz went on to be a very competent composer in his own right, albeit not in the ragtime genre, having written several waltzes and two operas. He also did very well in St. Louis real-estate, dying in 1953 with a good-sized fortune. Another associate of Wooster was Clarence Edmunds from Chicago, whose only known songs were those written with Frank as the lyricist. Then, of course, there was the Black Cat Rag co-composed with 18-year-old Ethyl B. Smith. It is not clear who contributed what to this piece, but it was either the music or the cover that helped it to take off. Black Cat Rag is not particularly friendly to many players in the A section since it involves a lot of moving octave work, but the effect is pretty stunning once a player gets it up to speed. In any case, the rag was the first of Wooster's publications that warranted a second, then third printing, and even distribution far beyond St. Louis.

He also did very well in St. Louis real-estate, dying in 1953 with a good-sized fortune. Another associate of Wooster was Clarence Edmunds from Chicago, whose only known songs were those written with Frank as the lyricist. Then, of course, there was the Black Cat Rag co-composed with 18-year-old Ethyl B. Smith. It is not clear who contributed what to this piece, but it was either the music or the cover that helped it to take off. Black Cat Rag is not particularly friendly to many players in the A section since it involves a lot of moving octave work, but the effect is pretty stunning once a player gets it up to speed. In any case, the rag was the first of Wooster's publications that warranted a second, then third printing, and even distribution far beyond St. Louis.

He also did very well in St. Louis real-estate, dying in 1953 with a good-sized fortune. Another associate of Wooster was Clarence Edmunds from Chicago, whose only known songs were those written with Frank as the lyricist. Then, of course, there was the Black Cat Rag co-composed with 18-year-old Ethyl B. Smith. It is not clear who contributed what to this piece, but it was either the music or the cover that helped it to take off. Black Cat Rag is not particularly friendly to many players in the A section since it involves a lot of moving octave work, but the effect is pretty stunning once a player gets it up to speed. In any case, the rag was the first of Wooster's publications that warranted a second, then third printing, and even distribution far beyond St. Louis.

He also did very well in St. Louis real-estate, dying in 1953 with a good-sized fortune. Another associate of Wooster was Clarence Edmunds from Chicago, whose only known songs were those written with Frank as the lyricist. Then, of course, there was the Black Cat Rag co-composed with 18-year-old Ethyl B. Smith. It is not clear who contributed what to this piece, but it was either the music or the cover that helped it to take off. Black Cat Rag is not particularly friendly to many players in the A section since it involves a lot of moving octave work, but the effect is pretty stunning once a player gets it up to speed. In any case, the rag was the first of Wooster's publications that warranted a second, then third printing, and even distribution far beyond St. Louis.There is no way to know if Frank was following the lead of the elder publisher John Stark, who took off for New York City in late 1905. However, after two years in St. Louis, funded largely by Black Cat Rag and a couple of recordings of his Universal Rag, Frank tried to establish himself in Manhattan, which at that time was a brutal environment for the independent publishers. In the substantial shadow of firms like Jerome H. Remick, Shapiro and Harry Von Tilzer, it was hard to get a foothold without good product and good advertising, plus some hefty investment. Even after five years in New York with moderate success pushing a limited scope of products, John Stark had retreated back to St. Louis. Frank set up near Tin Pan Alley at 127 E. 23rd Street, and was listed as a publisher in a special edition of the The Music Trade Review in late 1907. From this location Frank was able to get off another printing of Black Cat Rag and a couple of other pieces in his small catalog. However, no composers were making their way to his door, and that address was occupied by another concern by early 1908, so it is unlikely that he lasted any more than four to six months in New York. Before he left, Wooster sold off his remaining stock to music stores and his plates and catalog rights to dominant publisher Remick. Frank's final known composition, Blue Jay Rag went to John Stark for publication, selling moderately well. Universal Rag found its way onto at least a couple of piano rolls, giving the Wooster name a good boost, but by now it was too late.

From this location Frank was able to get off another printing of Black Cat Rag and a couple of other pieces in his small catalog. However, no composers were making their way to his door, and that address was occupied by another concern by early 1908, so it is unlikely that he lasted any more than four to six months in New York. Before he left, Wooster sold off his remaining stock to music stores and his plates and catalog rights to dominant publisher Remick. Frank's final known composition, Blue Jay Rag went to John Stark for publication, selling moderately well. Universal Rag found its way onto at least a couple of piano rolls, giving the Wooster name a good boost, but by now it was too late.

From this location Frank was able to get off another printing of Black Cat Rag and a couple of other pieces in his small catalog. However, no composers were making their way to his door, and that address was occupied by another concern by early 1908, so it is unlikely that he lasted any more than four to six months in New York. Before he left, Wooster sold off his remaining stock to music stores and his plates and catalog rights to dominant publisher Remick. Frank's final known composition, Blue Jay Rag went to John Stark for publication, selling moderately well. Universal Rag found its way onto at least a couple of piano rolls, giving the Wooster name a good boost, but by now it was too late.

From this location Frank was able to get off another printing of Black Cat Rag and a couple of other pieces in his small catalog. However, no composers were making their way to his door, and that address was occupied by another concern by early 1908, so it is unlikely that he lasted any more than four to six months in New York. Before he left, Wooster sold off his remaining stock to music stores and his plates and catalog rights to dominant publisher Remick. Frank's final known composition, Blue Jay Rag went to John Stark for publication, selling moderately well. Universal Rag found its way onto at least a couple of piano rolls, giving the Wooster name a good boost, but by now it was too late.A 1908 listing in the Gould's directory of Saint Louis showed that Frank was now running the Wooster Collection Company at his old digs in the Commonwealth Trust Building, with the promise of "Nothing Impossible." There is some irony to this as it is likely that Frank tallied up quite a debt in his aborted foray into big time publishing. Even after selling off his assets to Stark and others, he ended up having to work hard to get out of debt. The collection agency not having worked out, Wooster was found in the 1910 census working as a sole cutter in a shoe factory. He showed as having been recently married to Olive "Ollie" Wooster, and lived in a boarding house, making his situation seem even more desperate. As no record of their union was found, it may have been a domestic cohabitation situation, but a short term one as they were clearly separated before even a year was up. way. He and Olive divorced if they were indeed married. Then in mid-1911 Wooster was married to Finnish immigrant Saimi Lydia Kirnamsen. Around 1913 he decided on a change of pace that still involved the publishing business, and he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio where he started working with the Osborne Company, who produced advertising calendars for various trades. Frank and Lydia soon had a daughter, June, named for her birth month of June, 1915. By the time of the 1918 draft he was a well-established salesman for Osborne. For the 1920 enumeration Frank's status had improved quite a bit, and he was moving forward as an advertising man, leaving music behind. Late in the decade Frank went into general advertising in Chicago, Illinois, where he remained the rest of his life.

As of the 1940 census taken in Chicago, Frank and Lydia were living in the same home they had been in for at least a decade, and hosting a niece of Lydia's from Finland, Catherine Kussmaul. Frank showed his occupation as an advertising salesman, while Both Lydia and Catherine were cooks in a Chicago tea room. Wooster had retired from advertising by the time the 1942 draft record was taken in late April of that year. Lydia had died the previous year at age 58, so he was widowed and now living on 67th Street just outside the city center, with his daughter, now June Williams, living nearby. Frank Wooster died suddenly weeks later, just past his 57th birthday. But his legacy remains with us and his short run as a music publisher should still be considered as a worthy effort under trying circumstances. Ethyl and Frank's Black Cat Rag remains popular enough today that it is offered as a mobile phone ring tone by many companies. And midnight-hued felines the world over should be happy with the positive publicity given them by this one vibrant piano rag.

This is the first bio done on Wooster that the author knows of, and it was researched largely through public records, news reports, and the process of elimination. Also, thanks to Saint Louis historian and researcher Bryan Cather who sent some materials providing clarity for the time line.