Glover Compton is one of those frustrating ragtime figures who is often mentioned and was everywhere playing with everyone, yet little concrete information can be found directly about him. His narrative was also part of the core of the 1950 book They All Played Ragtime, including parts of the extensive interviews of Glover taken by authors Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis. Yet even that left several holes in his overall story. This biography represents an attempt to fill in more than has often been seen on this reportedly beloved and often busy ragtime performer.

Glover's mother, Laura Compton, had her first child, Maud, at just 13 or 14 years old. She was listed in the 1880 census in Bergin Knob, Kentucky, married to 22 year old farm laborer John Compton, and as 19 herself, with Maud as 1 year old. However, all subsequent records give her birth year as 1866 or 1867, so there may have been some obvious but understandable deception in this case. When she was around 17 to 18, Laura gave birth to Glover in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, about 50 miles north from Bergin Knob. The birth year is most consistently shown as 1884 on most documents, but on his draft record in 1918 it shows as 1883. His death record shows 1884, so that is the most consistent date. Laura was shown in Harrodsburg in 1900 working as a cook and as having been widowed. In that same census, Glover was listed as a boot black, a common occupation for black teens at that time. They also had two lodgers in their home, possibly for income reasons. Note that while his name was often shown as J. Glover Compton, he was listed consistently as Glover Compton on census records and travel manifests, and as Glover John Compton on his 1918 draft record. The origin of the J. Glover derivation of his name is unclear, but he may have originally been John Glover Compton after his father, having changed it by his teens.

Compton's name first appears as a pianist/entertainer in Louisville, Kentucky around 1904. The best-known pianist in town was "Piano Price" Davis, who fostered Compton to some extent and hooked him up with occasional jobs, sometimes by simply not showing up to his own gigs in favor of gambling instead. One venue mentioned was Jimmy Boyd's Café at 10th and Walnut where he played upstairs for $10.50 a week. Compton also says he visited the fair in St. Louis in 1904, but did not play in any venues there. It was during a 1904 musical tour to Louisville that a slightly disgruntled Tony Jackson, tired of the road, first met Compton. The two soon became friends, performing for a time at the Cosmopolitan Club. They also wrote a song together, which remains unpublished, but Compton recorded it in his later years. That piece, The Clock of Time, was reportedly repurposed in 1922 by composer J. Berni Barbour as the salacious My Daddy Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll), the song which ultimately provided the name for the genre of Rock and Roll. Jackson eventually went back to New Orleans for the next couple of years. It wasn't long before Glover was well regarded for his playing skills and reliability. But he didn't stay put for very long, choosing the life of an itinerant pianist for the next several years. In 1906 he spent time in Chicago playing at Elite Number 1 on State Street, run by Art Cardozo and Teenan Jones.

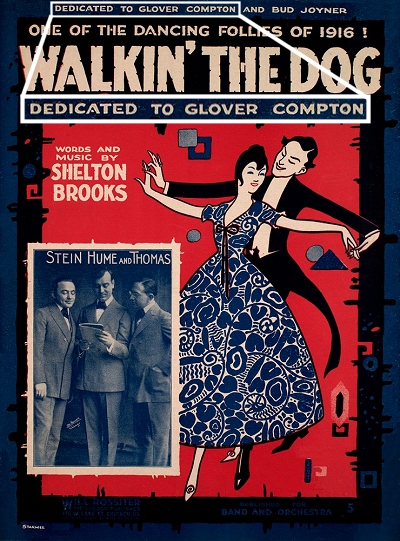

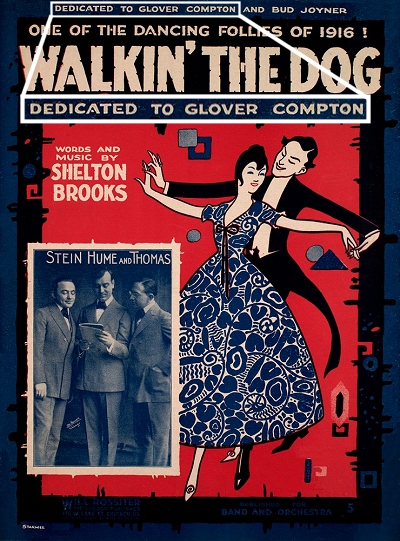

Despite his travels, Glover remained based in Louisville, and was listed there in 1910 in both the Kentucky and Federal census records with his mother Laura working as a laundress, and Glover as a dance hall musician. During his travels he spent time in Wyoming, Washington, New York and Chicago, the latter where he met up with one long-time partner and one partner from the past.  The long-time partner was singer Nettie Lewis who he married around 1911. Chicago became Compton's new home base, and he moved his mother Laura there as well. One of his most frequent haunts when he wasn't on the road was the Elite Club on South State Street, which also featured notable musicians like Jelly Roll Morton and Earl Hines during its 18-year life. The other partner was Tony Jackson, who had come to Chicago from New Orleans for good, and the two quickly got back together. They worked as a dual piano act from time to time over the next several years. Glover and Jackson exchanged many ideas as well, expanding the scope of how each of them played. Another occasional playing partner and friend was composer Shelton Brooks, who in 1916 dedicated his piece Walkin' the Dog to Compton and local actor Bud Joyner.

The long-time partner was singer Nettie Lewis who he married around 1911. Chicago became Compton's new home base, and he moved his mother Laura there as well. One of his most frequent haunts when he wasn't on the road was the Elite Club on South State Street, which also featured notable musicians like Jelly Roll Morton and Earl Hines during its 18-year life. The other partner was Tony Jackson, who had come to Chicago from New Orleans for good, and the two quickly got back together. They worked as a dual piano act from time to time over the next several years. Glover and Jackson exchanged many ideas as well, expanding the scope of how each of them played. Another occasional playing partner and friend was composer Shelton Brooks, who in 1916 dedicated his piece Walkin' the Dog to Compton and local actor Bud Joyner.

The long-time partner was singer Nettie Lewis who he married around 1911. Chicago became Compton's new home base, and he moved his mother Laura there as well. One of his most frequent haunts when he wasn't on the road was the Elite Club on South State Street, which also featured notable musicians like Jelly Roll Morton and Earl Hines during its 18-year life. The other partner was Tony Jackson, who had come to Chicago from New Orleans for good, and the two quickly got back together. They worked as a dual piano act from time to time over the next several years. Glover and Jackson exchanged many ideas as well, expanding the scope of how each of them played. Another occasional playing partner and friend was composer Shelton Brooks, who in 1916 dedicated his piece Walkin' the Dog to Compton and local actor Bud Joyner.

The long-time partner was singer Nettie Lewis who he married around 1911. Chicago became Compton's new home base, and he moved his mother Laura there as well. One of his most frequent haunts when he wasn't on the road was the Elite Club on South State Street, which also featured notable musicians like Jelly Roll Morton and Earl Hines during its 18-year life. The other partner was Tony Jackson, who had come to Chicago from New Orleans for good, and the two quickly got back together. They worked as a dual piano act from time to time over the next several years. Glover and Jackson exchanged many ideas as well, expanding the scope of how each of them played. Another occasional playing partner and friend was composer Shelton Brooks, who in 1916 dedicated his piece Walkin' the Dog to Compton and local actor Bud Joyner.In the mid-1910s wanderlust struck Compton again for a while. There is a story about Glover that comes from when he worked on the Barbary Coast in Northern California, as early as January of 1913 by his own reckoning. One of his favored venues there was the St. Francis club between Pacific and Broadway. According to West Coast pianist Sid Le Protti who he met there, Le Protti played one of his original tunes for Compton who quickly learned it. In 1915 Le Protti heard his tune played again, but this time it was named Canadian Capers. Evidently Compton had played it back in Chicago at the repeated request (with the lure of dollar tips) of pianist Henry Cohen, and Cohen collaborated with three of his friends to "compose" the piece Canadian Capers, which included Le Protti's melody in the B strain. At a later time when Le Protti asked Cohen about this, the latter pointed to Compton as the one who taught him the melody, and when asked if he could use it, Compton had no argument. Compton confirmed this story at some point as well.

It is known that Compton was on the road in the latter part of the 1910s, but work in playing ragtime was not always available. He says he "palled around with Jelly Roll Morton" during the latter's visit to the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition San Francisco. Most of the local performers played at the Exposition because the Barbary Coast clubs were temporarily shut down during the event. Then he went back to Chicago for part of late 1916 through early 1917, playing with Nettie at the Panama Café until it was shut down. Another act playing there, the Panama Trio which included Florence Mills and Ada "Bricktop" Smith, helped forge a friendship with the latter that would later provide him a great European connection.

From late 1917 to 1918 Glover and Nettie spent six months down in Los Angeles at the Waldorf Cafe while Jelly Roll played at the Cadillac. While they did perform along the Barbary Coast following that gig, Compton's September 1918 draft record shows him employed as a porter for the Southern Pacific Railroad, with the couple living in the Oakland/Alameda area. He also appeared in 1920 voter rolls there, although by mid-1919 he and Nettie went up to Seattle, Washington for a while where he played at the Entertainer's Night Club on Main Street with a small combo. The Comptons were shown there as late as January of 1920 in the census, sharing quarters with some of the other entertainers. Glover is listed as a "cabaret musician" and Nettie as a "cabaret actress." Curiously his birth state is listed there as Missouri, yet it is clearly the same person. Since the 1920 census was not taken consistently at that same time across the country, they managed to show up in it again in February in Chicago, back with Laura, who was working as a cook, and now with Nettie's mother living there as well. It is also indicated that Glover owned his home at 3641 Prairie Avenue, so it is probable Laura had been living in it while the couple had their adventures out west.

With the jazz age in full swing in Chicago, Glover readily adapted his style, and was soon playing with musicians such as jazz and blues singer Alberta Hunter, clarinetist Jimmie Noone, and drummer Ollie Powers, both of the latter disciples of leading jazz performer Joseph "King" Oliver. For the next few years he would travel back and forth between Chicago and Seattle with small bands. Compton recorded a couple of energetic sides in 1923 with Ollie Powers' Harmony Syncopators later known as J. Glover Compton and the Syncopators. Glover's group performed for some time at the Oriental Café on South State Street, in the former location of their old haunt, the Panama Café. There he worked with both Ms. Hunter and Nettie. Another mentioned venue was the Dreamland Café where Oliver would join Compton's band on

Monday afternoons for "Blue Monday" sessions. He also ventured to New York on a few occasions, cutting a couple of sides with Hunter as well (although incorrectly billed as Grover Compton). The sultry singer had also recorded with Duke Ellington and Perry Bradford during that period. Yet Compton was not able to achieve the status of many of his peers, perhaps in part because he was not writing his own material as most of them were. Even in some travels with Jelly Roll Morton he was relegated to the role of relief guy and sidekick. This frustration eventually drove him to try Europe, and starting in 1926 he spent much of the next 13 years commuting between Chicago and Paris via New York. Compton was obviously not living full-time in Europe like some of his peers, including the notorious soprano sax player Sidney Bechet, and appeared in Chicago in the 1930 census as an accompanist, Nettie with no occupation listed, and rooming with some other vaudeville actors.

|

Compton settled in at a cafe started by Chicago expatriate, Ada "Bricktop" Smith whom he had reconnected with. It was the famous Chez Bricktop in Paris. Ada had first invited Compton over to France in 1926 after her pianist was killed by his girlfriend in a dare situation that he finally lost. Glover played there with the existing group, The Palm Beach Six. Compton was described during this period as an early version of Willie "The Lion" Smith, a consummate entertainer, complete with the cigar hanging out of his mouth, the large repertoire, and his direct engagement with the audience. Another place he frequented was the Royal Box in Paris owned by Joe Zelli. While the time spent in Paris seemed to be good for Glover's career and finances, it did not help his status in the U.S. as many simply forgot who he was. But the French knew who he was, particularly after the famous shooting incident of December 20, 1928.

Many of the transplanted musicians were gathered at Bricktop's early that morning when an argument broke out between soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet and banjoist Gilbert McKendrick. The cause was evidently a dispute about chord changes of all things, which Bechet found offensive to his musical intellect. Another story had to do with who had failed to buy a round of drinks. Whatever the cause, Compton, who already had an ambiguous relationship with Bechet going back several years, evidently tried to intervene. As McKendrick emerged from the bar, Bechet, who had gone to fetch his firearm, started shooting. McKendrick was completely missed, but two witnesses were wounded, and Compton was shot in the leg. Both men got 15 months but served a year. Compton spent several months in the hospital, and says that Bechet and McKendrick had promised to pay his bill, but they were never able to. When released in 1929, Bechet found out that Compton was planning on suing him for compensation for the wound. Bechet quickly got word to Compton to watch out for his other leg, and the suit idea quickly evaporated. Even though Bechet and McKendrick became friends to some degree, Compton remained on Bechet's bad side from that point on. Fortunately for Glover, Bechet and McKendrick were asked to depart France permanently soon after their sentence was served. Compton continued to play at Bricktop's, eventually favoring a long-term gig at Harry's New York Bar owned by jockey Ted Sloane, also in Paris.

Glover and his wife continued to cross the Atlantic into the late 1930s, with one final voyage documented in October 1939. He came back to New York City this time, forced in part by the onset of war in Europe, playing in a jazz piano joint, reportedly the type where people are there to drink and talk, not to listen to music. Within a couple of years, the Comptons returned to Chicago, and he reassociated himself with Noone for many years. Author Rudi Blesh found him there in 1949, and interviewed him at length for his upcoming book They All Played Ragtime, getting a wealth of information (although not entirely accurate) about various ragtime players in the Windy City.

The 1950 enumeration showed Glover and Nettie in Chicago, with Glover touted as night club entertainer. In the early 1950s he opened his own bar in Chicago, a place where he could have some control over the playing environment. It was here that he spent his last few years, and seems likely that it's where his 1956 taped interview set with archivist Birch Smith took place, Compton's only true recorded piano solos. Another artist that spent considerable time with Compton and befriended him was rising star Johnny Maddox from Gallatin, Tennessee. Johnny had a considerable number of memories and interesting stories about Compton from talking with him in Chicago.

Glover Compton suffered a debilitating stroke in 1957, and finally succumbed in 1964 at age 80. We have only one piano rag - which may or may not actually be his (he claimed he wrote the music to Chris Smith's Honky-Tonky Monkey Rag) - and a handful of recordings to remember him by, but we also have great stories and his evident influence on some of his peers as part of the makeup of the collective of ragtime performance.

Thanks to Adam Swanson who provided a couple of extra elements on Compton, and Australian historian Bill Egan who came up with more of his association with Ada Smith. Some of the narrative comes from They All Played Ragtime by Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, and from unpublished notes by Rudi Blesh, but the bulk was pieced together by the author from recordings and public and private archival records.

Compositions

Compositions