There are some stories in the history of American music that have definitive intersections with others, and it can be hard to separate many parts of their story from the other. This is one of them, and while both biographies dealing with this couple do have separate beginnings, and some of the content in the middle is unique to that individual, for the most part they are tandem in many ways. It is a story of one of the more enduring, successful, and at times controversial couples of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley - Gertrude and Max Hoffmann.

and at times controversial couples of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley - Gertrude and Max Hoffmann.

and at times controversial couples of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley - Gertrude and Max Hoffmann.

and at times controversial couples of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley - Gertrude and Max Hoffmann.Katherine Gertrude Hay was born in San Francisco, California, to John Hay and his Irish immigrant bride Katherine Brogan. She was the last of seven children born to the couple, including Mamie (1871), Nellie (1872), John Robert (5/1875), George Henry (3/9/1877), Margaret (9/25/1878) and Rose Marie (10/27/1880). John, who had come west from Maine, was a foreman for a molder works in the fast-growing town by the bay. Katherine's musical and overall education was obtained at a Catholic convent in or near San Francisco. When she left school she started working on the stage in various burlesques or vaudeville theaters around town, billed using a slightly modified variation of her name, Kitty Hayes, beginning perhaps as young as sixteen.

John died within a year of the 1900 enumeration, taken in San Francisco, which showed that Katherine was working as an actress. Around 1900, Katherine was spotted by actress Florence Roberts while playing a French Dancer in an opera at the Alcazar Theater in San Francisco, and she encouraged the soubrette to consider a career in dance. She was working up to ten performances each week, earning a quarter for each performance, totaling around $2.50 in her weekly pay envelope.

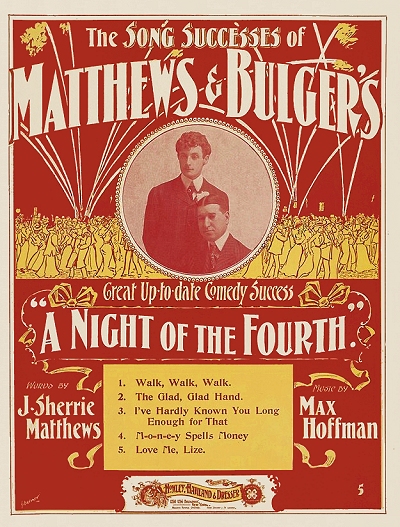

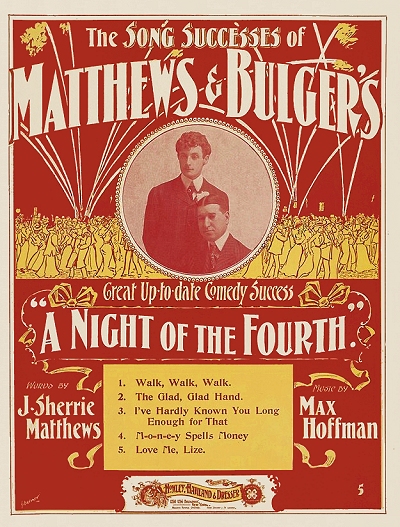

At the age of seventeen Katherine, who was now going as Gertrude Hayes, signed on with a show starring J. Sherrie Matthews and Harry Bulger, and followed them on a continental tour. She had a small role in the musical play The Night of the Fourth by George Ade that started in San Francisco and worked its way through the Midwest in late 1900 toward New York. It received tepid reviews and many adjustments during the trip. The play debuted on Broadway at Hammerstein's on January 21, 1901, and went downhill from there. One review in the New York Dramatic Mirror summed it up as, "absolute drivel, pointless chatter, and purposeless dialogue. Why anyone should have produced such stuff is a question beyond answering." The debacle closed after fourteen performances.

It received tepid reviews and many adjustments during the trip. The play debuted on Broadway at Hammerstein's on January 21, 1901, and went downhill from there. One review in the New York Dramatic Mirror summed it up as, "absolute drivel, pointless chatter, and purposeless dialogue. Why anyone should have produced such stuff is a question beyond answering." The debacle closed after fourteen performances.

It received tepid reviews and many adjustments during the trip. The play debuted on Broadway at Hammerstein's on January 21, 1901, and went downhill from there. One review in the New York Dramatic Mirror summed it up as, "absolute drivel, pointless chatter, and purposeless dialogue. Why anyone should have produced such stuff is a question beyond answering." The debacle closed after fourteen performances.

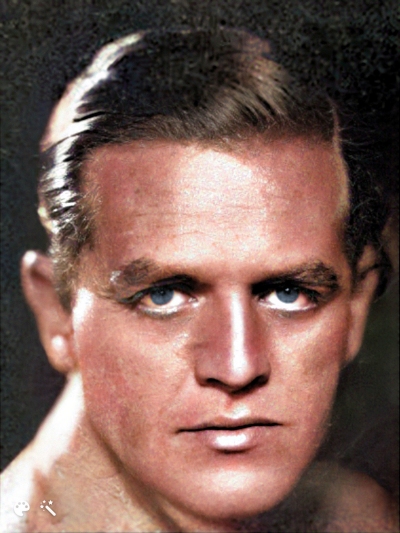

It received tepid reviews and many adjustments during the trip. The play debuted on Broadway at Hammerstein's on January 21, 1901, and went downhill from there. One review in the New York Dramatic Mirror summed it up as, "absolute drivel, pointless chatter, and purposeless dialogue. Why anyone should have produced such stuff is a question beyond answering." The debacle closed after fourteen performances.Not all was lost, at least for Gertrude. The music director at Hammersteins in early 1901, who had also provided the music for the songs in the play, was one Adolph Eugene Victor Maximilian Hoffmann, usually abbreviated to Max Hoffmann (1873-1963). (Note that Hoffmann was often seen as Hoffman in some publications, but the former will be used here.) He was a Polish immigrant who was raised mostly in Saint Paul, Minnesota. There were rumors that his title was Baron, but that appears to have been applied by one of his early press agents. By the late 1890s Max had attained some notoriety as an arranger of ragtime tunes, including his hit Ragtime Medley. He had become the director of the Broadway Theater before 1900, and was also arranging and scoring vaudeville shows as well, writing music specifically for a number of well-known troupes, including those of producers Marcus Klaw & Abraham L. Erlanger. Having composed the music for the play with Matthews, he was engaged to rehearse and conduct the show, touring with it in December and January, and to try out new ideas when needed. Very soon, Gertrude became one of those new ideas. Max was married to singing comedienne Atlanta J. "Attie" Spencer at the time, who had introduced some of his works on the stage during their six-year marriage. However, he would soon leave his wife and set his sights on the vexing and alluring young dancer. Gertrude was named as a co-respondent during their divorce hearings, but given that Attie would quickly remarry within weeks, only to divorce within another year, she was likely partially responsible for the dissolution.

After a whirlwind romance, Gertrude, now eighteen and Max were married on April 7, 1901, virtually hours after his divorce had been granted in Chicago, during a stint in Norfolk, Virginia with the Bijou Musical Comedy Company. Perhaps as a formality they also had a ceremony the following day in Manhattan, New York. Max, Jr. was coincidentally born in Norfolk during another tour of the troupe in December 1902. During that period of 1901 into 1903, Max wrote some of the songs for the Bijou company, and Gertrude would both choregraph and dance in selected numbers. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.

During that period of 1901 into 1903, Max wrote some of the songs for the Bijou company, and Gertrude would both choregraph and dance in selected numbers. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.

During that period of 1901 into 1903, Max wrote some of the songs for the Bijou company, and Gertrude would both choregraph and dance in selected numbers. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.

During that period of 1901 into 1903, Max wrote some of the songs for the Bijou company, and Gertrude would both choregraph and dance in selected numbers. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.Within a few months of their son's birth Gertrude was already dancing at the Paradise Roof Garden on top of the Victoria Theater in New York City, run by no less than Oscar Hammerstein, Sr. The boss was impressed, so Max was hired to write and arrange for them, and Gertrude, all of twenty, was engaged to assist director Frank Tannehill with rehearsals and choreography. Her main assignment was the Punch and Judy Company, a vaudeville revue that played at the Paradise from June through early September of 1903. More opportunities came for Gertrude over the next couple of years as she built her reputation and dance repertoire as both a dancer and creative choreographer.

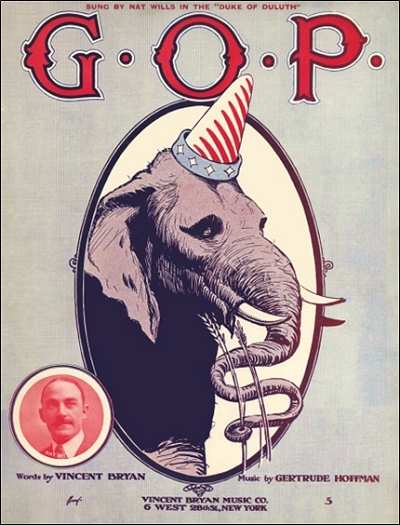

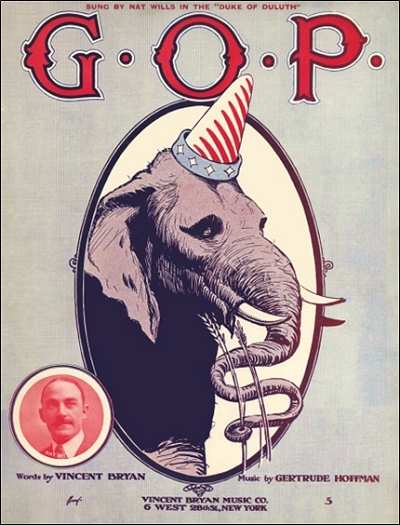

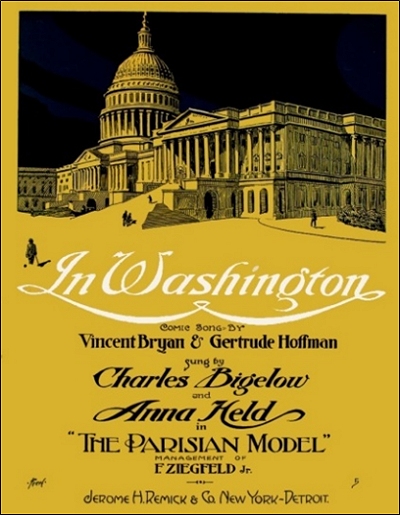

While Gertrude was busy at the Paradise, Max, who had written several solo efforts over the past two years during their tour with the Bijou company, was engaged by Gus and Max Rogers to become their new musical director and composer for their string of popular Rogers Brothers shows, an association that would last for several years, making the couple quite comfortable in their Manhattan home. In 1905 Gertrude teamed with lyricist Vincent Bryan, who had his own small publishing concern at that time, and had been writing with Max. They wrote a few songs that were published over the next several months, the last couple of them issued by Jerome H. Remick. Each piece was likely scored by Max, although he did not take credit. One of them, G.O.P. after the Grand Old [Republican] Party is oddly timed, since the last election had been months before, but was likely associated with the show Fantana, or perhaps The Duke of Duluth. The remainder of the pieces were also from various shows.

In late 1906 theatrical entrepreneur and producer Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., was staging A Parisian Model, a show which saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater. Gertrude provided some of the music for songs used in the production, and was somehow involved on stage during previews. In a scene worthy of the storyline of the film 42nd Street, a lead performer became ill and Gertrude was brought in as a ringer. Performing the song I Just Can't Make My Eyes Behave (ironically the hit but the only one that Max was not involved in writing) in the manner of Ziegfeld's French wife of the time, Anna Held, Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. She would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.

Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. She would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.

Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. She would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.

Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. She would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.The following year, Ziegfeld staged the first of what would become over a quarter of a century of his famed Ziegfeld Follies, which involved both Gertrude and Max behind the scenes. Max was the musical director and a couple of his songs had been interpolated. At some point at least one of Gertrude and Vincent's songs had also been used, and she contributed to the ambitious choreography. Max would have more involvement in the Follies over the next few years as Gertrude found her own way as a free-lance dancer on Broadway. Her most literally arresting act was yet to come.

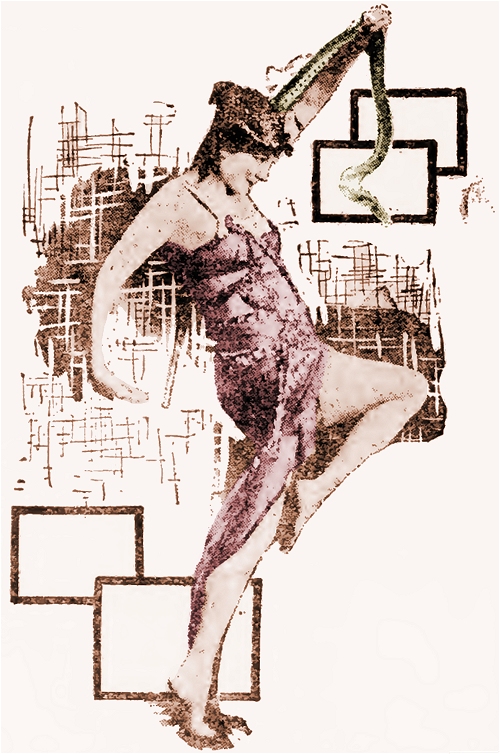

When Richard Strauss first had his 1907 opera Salomé staged at the Metropolitan Opera, it was backed by J. Pierpont Morgan, William K. Vanderbilt and August Belmont, some of the richest men in the world. The story was so shocking that they ended up working to get it removed from the stage. So when Gertrude was offered the sketch A Vision of Salomé, she took the character to heart and strove to replicate her vision of the famed stepdaughter of Herod Antipas who was readily seduced by an over-the-top performance engineered to have her mother's wish fulfilled - that of delivering the head of John the Baptist. While that vision was disturbing enough in print, bringing it to life was too much for many. In fact, after the initial performance, New Yorkers flocked to the theaters in large numbers so they could be equally disgusted by Gertrude's sexually charged performance.

To learn the role and the dance, Gertrude actually went to London with her husband under false pretenses, agreeing to a contract to work in a show with Maude Allan, who was doing a similar dance at that time.

After about a day Gertrude figured out the general crux of the dance, then vacated the theater, sailing back to New York as quickly as possible, creating a legal issue for any future performances in London. Concerning the Strauss production on which Gertrude's performance was derived, Theatre Magazine noted that the part that most "offended" the crowd was when the head was delivered and Salomé increased the erotic fervor with which she danced while kissing the head, something that "sickened the public stomach." Sam M'Kee of the New York Telegraph gave his own account:

|

Suddenly, she turns and sees the head of John the Baptist. She takes it with a combination of eagerness and aversion… places the head before her and in wild abandon, as if to conquer her loathing, begins a tempestuous dance. She is garbed with draperies and gewgaws of a bloody age… but the effect is that she is naked.

Perhaps Gertrude was simply too seductive. Efforts to stop the show did nothing but publicize the staged atrocity, which went on to shock audiences in other cities around the East, even resulting in the occasional arrest or performance canceled by a local judge. One such incident took place in Kansas City, Missouri, in March 1909, where Gertrude and Max were appearing in The Gay White Way at the local Shubert Theater, part of the company's chain. She was arrested for performing in public "bare-footed and bare-ankled and almost bare-kneed," as per the Kansas City Journal. She was enjoined from performing either her famous Salomé dance in that city unless she covered her knees and feet, so she simply danced her similarly garbed Spring Song dance instead. In response to the criticism and the alleged public offense of her audiences, Gertrude gave the Journal the following:

so she simply danced her similarly garbed Spring Song dance instead. In response to the criticism and the alleged public offense of her audiences, Gertrude gave the Journal the following:

so she simply danced her similarly garbed Spring Song dance instead. In response to the criticism and the alleged public offense of her audiences, Gertrude gave the Journal the following:

so she simply danced her similarly garbed Spring Song dance instead. In response to the criticism and the alleged public offense of her audiences, Gertrude gave the Journal the following:Do you hear that?… Did you see that audience? Did you see any people with low brows in that audience? Do they look coarse, unrefined, ill bred? No, certainly they don't. What does the so-called religious element of Kansas City think I am doing over here? Do they think I get out on the stage and wriggle? Do they think the audience giggles?

I have given my dances all over the Eastern section of the United States. I played in the leading cities of New England where the Puritans came from and where their descendants live and thrive and still preach purity. Intellectual audiences, audiences of brain and a taste for art saw my dances. I played to an audience made up entirely of Harvard men while in Boston. I played to an audience made up almost entirely of Yale men when we played in New Haven. When we played in Springfield, Mass., more than half of the audience was composed of girls attending Smith college. They came over thirty miles to see my performance. They represented some of the richest, most intellectual families of the United States. They didn't blush. They had nothing to blush for. They applauded.

Who are these people who rant about something they have never seen? They are hypocrites, to begin with. Why do they seize on this performance, when they have ignored other theatrical performances which might have given them some excuse for going to court? If these people object to my dance why don't they go to your art academies and tear down the nudes. Why don't they close up the art academies and prevent nude women from posing for nude pictures? Why don't they? That's art, they will say, if they have intelligence. So it is. And this dance I give is art, classic art.

Gertrude was similarly arrested in Manhattan on Hammerstein's Roof that same July, and the crux of her case concerned the definition of "tights" and what they should cover. There has long been speculation, even as events were unfolding, that some of these arrests were staged for publicity purposes, although little evidence has been found to either support or deny such charges, which nonetheless ring true. Gertrude would dance other erotic roles in scanty clothing that resulted in the same result over the next few years – selling tickets to a public willing to have their Victorian morals shocked senseless. She was not the only stage persona to bring a salacious Salomé, some suggesting that dancer Ruth St. Denis' was "out-Saloméing all the Salomés." But Gertrude was still one of the most memorable.

She even had reportedly her extremities insured for $2500 per week at one point – or at least a story was leaked that she did – in case anything was damaged and she could not perform. Whether the costs of the arrests were covered by insurance is unknown. Max provided a score for Vision of Salomé for its run starting at the Hammerstein Theatre's Roof Garden, and critic, in attempt to be clever, noted that his "music for the act was vague and blue. Get that? Vague and blue."

|

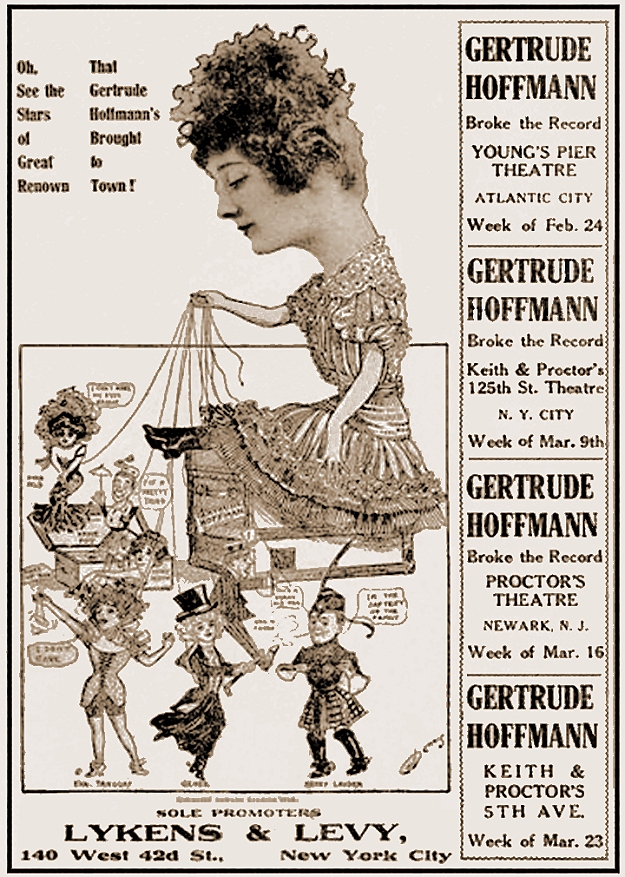

Continuing to provide choreography services to Ziegfeld and Hammerstein, Gertrude tried to elevate the level of serious dance as well. Building on her fame as Salomé, she further created dances based on other historic seductive women, including Cleopatra of Egypt and Scheherazade of 101 Arabian Nights lore. In early 1911 Gertrude brought part of the famed La Saison des Ballet Russes (Session of Russian Ballets) to New York. For the event, Max conducted a 75 piece symphonic orchestra. In addition to dancing, she also became a reasonably good mimic on stage at Hammerstein's Roof Garden of other famous personalities ranging from the equally sultry Eva Tanguay to British music hall singer Vesta Victoria, and even the foppish comic with the large family, Eddie Foy. Max was there in many cases providing musical leadership or input for her act. The 1910 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed Max as a theatrical musician and Gertrude as a theatrical actress, with three years trimmed off her age for good measure.

While Gertrude appears to have all but quit composing after 1911, it is notable that she became famous for a piece composed by her husband, The Gertrude Hoffmann Glide, to which she had a dance routine in the 1912 show From Broadway to Paris at the Winter Garden Theater. Its popularity in both sheet music and recorded form helped to further spread her name and fame around the country. The show itself, which following previews in Boston initially ran from November 1912 to late January 1913, was well received by the critics. As one of them noted:

Anything like remotely intellectual purpose… was made subordinate to what should delight the eye and the ear…

Gertrude Hoffmann, who has added bicycle riding to her other arts, capered through a dance called "The Garden of Girls," which was mythological and poetic and on the plan of the spring dance she used to do in the vaudeville theatres. Then she did some of her imitations. She wore her extravagant dresses that gave her the look of one those that have feathers and bite and sang in a childish treble.

After her run of the show on Broadway, Gertrude planned to tour in her own act. One of the venues she booked was Alexandra Theater in Toronto, Canada, but according to The New York Clipper of March 29, 1913 she was barred from presenting her act as the theatrical censor of the city "saw it in the United States."

From August through October 1913, the Hoffmanns embarked on a national tour with French singer Émilie Marie Bouchad (a.k.a. Mlle. Polaire) and British dancer Lady Constance Stewart-Richardson, each of them bringing along their own music directors as well, and presenting art song and dance, ending in New York City.

|

Gertrude then took her own revue on a national tour through the end of the year. In advertising for talent for her show, she noted that they should be girls 16-18 years old, experience not necessary, and a pretty face and figure were the only requirements. This was the beginning of what would become the famous Gertrude Hoffmann Girls. The opening week was popular enough that it created a dangerous situation at The Playhouse in Wilmington, Delaware, where it was staged. The crowd on Monday night, November 3, 1913, was so great that some people were nearly crushed when the house was opened, and a railing on one of the stairways gave way, sending several customers as much as ten feet down to the floor. Several hundred potential audience members were left out in the cold as all seats were sold and the standing room only section filled immediately. The show received a glowing review, including for the orchestra led by Max.

Up until the end of the tour of the power trio of women entertainers ended, Gertrude's career had been handled for some time by Morris Gest, but he gave up that role "in despair" when he was unable to keep that ball rolling due to Mrs. Richardson and Mlle. Polaire objecting to her near nudity on stage and other errant behaviors. So for a time, Gertrude was facilitating her own booking work. However, in the Spring of 1914 the large United Booking office took over the duties, leaving her free to perform and develop new acts.

Gertrude spent a second year absent from Broadway stage shows, instead playing the bigger vaudeville houses, like the Colonial, B.F. Keith’s, and even the storied Palace in Manhattan. Just the same, she was encountering the occasional boycott when on the road, often from religious groups that found the tone of her act objectionable, and were able to persuade locals to avoid going to her shows, which she had to cancel from time to time. Yet some reviewers insisted that her revue had a lot of merit and that she entertained "without offense." When he was not engaged with other shows, Max traveled with his wife to conduct the orchestra. Yet they still found some time during an occasional hiatus to relax in their new Long Island home, and even participate now and then in local community activities, often as the guests of honor.

|

The 1915 New York census echoed the 1910 record, showing that the Hoffmanns also had two live-in domestics, necessary to help take care of Max, Jr., who was now in his early teens. It would be another busy year for Gertrude and Max. In addition to her own 1915 Revue, which toured into the spring, she was featured in a "vaudevilleized" version of the Max Reinhardt German play Sumurun (sometimes referred to as One Arabian Night), a "wordless play" that had originally opened on Broadway in 1912. It ran at the Palace for at least part of the summer, followed by B.F. Keith's, and then the Orpheum in Brooklyn that fall. This now-famous pantomime featured Gertrude in the title role of a sheik's main slave girl in love with another man, so seductive dancing was clearly involved. There was even a water tank on stage used for a salacious bathing scene involving a bevy of beautiful harem girls. In preparing for the role, she took copper baths to darken her skin. Due to the ongoing war, however, the solution to counter the browning effect, which was made in Germany, was unavailable. So for some months Gertrude went about with an alarmingly dark complexion. Max was at the podium for the full run, providing appropriate music for the pantomime, and both Hoffmanns received positive reviews. Interviewed about her dancing style and her process, Gertrude unabashedly offered the following observations:

Beauty is not only a matter of lines and color… Arms that are regular in line and movement will gradually become rounded and curved in motion and repose through using free, large relaxing movements. Five minutes' practice twice a day should be followed. The swan-like throat is simply the result of dancing, which involves a bending back of the head. The back is always the hardest task to make supple and at the same time stronger. Just simple head bending at first. Then gradually extending the bendings to the waist muscles, always keeping the hips back in place to localize the curve of the back, the vertebrae being inflexible from years of the one straight or bent forward position. It is a slow task to acquire a supple spine, but the natural freedom of body movement gained is well worth the effort. The splendid freedom of hip movements observed in the leaps of my dances is gained through simple skipping and running. Boys naturally run and leap like this, but as soon as a girl puts on long dresses she must act as though in a straitjacket, unless she is fortunate enough to have an athletic court or indoor gymnasium. This big, free action increases the circulation of the abdominal organs, stimulates the digestion and breaks down any superfluous flesh of the waist and hips. By taking these leaps with the arms high above the head, as in playing ball, the hips will become slender, yet rounded, so much desired by every woman. The muscles of the lower leg will grow long, the superfluous flesh around the ankle will give way to thin, hard muscular tissue, and the line of the leg will become long, slender and tapering, so lovely to see in the Greek sculpture preserved for us. By dancing in the bare feet the toes spread in their natural lines, the big toes continue in the straight inner lines of the feet, leaving a free space between the big and the second toes. In the elevations the muscles of the instep are stretched and strengthened, creating a high arch and corresponding high instep.

In 1916, Gertrude was contemplating going into motion pictures. Her asking price was reportedly $40,000 per feature. The figure changed slightly in 1917 with a purported deal to appear in three films for a total of $75,000.

This clearly was high by film actor standards of that time, and as a result she apparently was never in a film—at least none that are extant or documented. Following a late winter tour, she enjoyed a revival of Sumurun in the spring, then got a regular gig at the recently opened Cocoanut Grove venue on the roof of the Century Theatre. She also appeared in the musical Dance and Grow Thin in the theater downstairs, which was led by Max. The Hoffmanns provided a variety of stage fare for both into early 1917, after which they abandoned their posts for new horizons. The first of those was the Gertrude Hoffmann 1917 Revue, which played throughout the spring.

|

World War I was problematic for the entire country, and Broadway and the music world were hit relatively hard as many men were drafted, and some would never return. Through enlistment and draft, Gertrude lost six successive dancing partners in 1916 and 1917. Near the end of the war, many members of the Broadway community were stricken by the Spanish Flu pandemic, which caused the deaths of some of them. To fill in the gap, Gertrude called on her son, Max. Jr., to become her next partner. He had just entered Cornell to pursue a course of study in civil engineering, but Gertrude was desperate, and audiences still were looking for entertainment to forget their woes of the time. Playing in her Revue at the Winter Garden Theater in late 1917, the 16-year-old was evidently up to the task, and smitten by the allure of the stage, quickly become quite adept at both dancing and acting. After a full season he went back to Cornell to finish his degree. Around that same time in the summer of 1918 Max and Gertrude moved into their new custom-built home at Sea Gate on Coney Island.

Touring the country during the early days of World War I, Gertrude and her husband continued to make the headlines now and then for supposedly scandalous behavior. Even as late as 1917 as public morals and fashion trends were evolving, her stage outfits still caused problems for some of the community gatekeepers for public decency. She had upped the ante a bit not only in trimming down her wardrobe for 1918, but now dancing with snakes as well in her Revue for that year. In early December 1918, Gertrude and Max were called into the courtroom in Saint Louis, Missouri, where he assured the judge that even as Salomé she was wearing three layers of tights reaching down to her knees. Two weeks later on Christmas Eve, Max and two others from the company were hauled in front of a magistrate in Omaha, Nebraska, which was a dry state, on the charge of having transported liquor there in the form of wine and champagne from Kansas City, Missouri. Max was later acquitted based on the premise that his car was his home while traveling, and produced a telegram from Gertrude's doctor claiming, thinly, that "champagne was necessary to the health of the star."

Throughout the late 1910s Gertrude pulled in more credits for her work on stage and behind the scenes, mostly with large ensembles in revues or revivals. However, around the time the war ended she made the choice to work as a single - just Gertrude and a small orchestra with no major supporting players. So for part of 1919 she and Max traveled the United States, including longer stints in Chicago, Buffalo and Philadelphia, providing a high-class solo act that was typically courteously reviewed, if not enthusiastically. A smaller-scale tour was undertaken in early 1920, followed by a similar itinerary in 1921, one that introduced her exotic “White Peacock” interpretation.

Just the same, now in her late thirties, Mrs. Hoffmann’s reputation remained intact in a number of ways, as evidenced by this colorful Chicago Tribune review of November 3, 1921:

|

MISS GERTRUDE HOFFMANN is at the Majestic again, with her Madonna countenance and her wicked ways, dancing as serenely as ever through the most disturbing of choreographic incidents. No one can denote a mood of abandoned devilry and be as prim about it as she. This bizarre quality she emphasizes in the first of her offerings, something flamingly barbaric in which she issues from a huge chest wearing nothing much except the chains of a slave to simulate terror and desperate cunning as her new principal dancer M. Leon Barte lays about her with a whip. It is outré and decadent and I suppose I should know what it is all about… And, as always, the fatherly, gray haired Max Hoffmann sits at the piano, getting more blare and infectious rhythm out of his little band of musicians than most conductors can get from a full orchestra.

The Volstead Act of 1919 which spurred the National Prohibition of alcohol starting in 1920 was not kind to vaudeville, an entertainment that, by that time, arguably required a bit of lubrication to enhance the experience. It was much easier to serve up jazz in a speakeasy than it was to dispense illegal liquor in a loosely-formatted theater. So, the postwar full Broadway shows and revues tended to lure the better writers and musicians, while vaudeville houses started to empty. This worked for Max who was both valuable flexible in this regard. However, despite Gertrude's talent, beauty and history, at that time it was a lot to ask people anywhere in the country to come watch a 37-year-old solo dancer with only moderate comedic and singing skills in a sparsely populated venue. By this time, Gertrude was doing less on stage and Max was performing more in front of it. However, she soldiered through with a cheery attitude, as conveyed in a December 1921 interview in the Brooklyn Standard Union:

If you wish to feel young and remain young, you must smile… There have been times in my life when I didn't laugh, when I felt I had the weight of the world on my shoulders, and as a result I had to go to bed and receive medical aid. But that time is past and gone. I no longer have any fear, because I have learned the divine truth, that 'God is love,' so I continually go on my way rejoicing.

In years gone by I would get into a city and if the hotel accommodations were not as I thought they should be, I fussed and fretted — or if the dressing rooms were not large enough to be comfortable, I became hysterical; but now, and for the past few years, I have realized how wrong I used to be, aa a direct result I laugh; it is a great joke. Dear me, when I think of the days and hours of misery I might have saved myself and people around me, and, too, the funny little lines that creep around one's mouth from fretting might never have had a chance to slip upon me had I known then to always smile… I find that smiles are most infectious and when one starts to spread the germ you very shortly find everyone suffering from over-pleasantness…

There is so much sorrow and unhappiness in this old world of ours anyway, that I believe it is part of the task God planned for me, to make others happy, and if in the tiniest way, through smiling or through my work I am able to lighten someone's burden, it will never be said that Gertrude [Hoffmann] did not do her duty.

Gertrude, finding less opportunity for bookings, was still active and restless, feeling a continuing need to contribute to the stage and the art of dance. She was not without work, having created the revue Hello Everybody with Max for the Shuberts in late 1922, and touring with The Mimic World in early 1923.

But as a solo act or headliner, her name was starting to fall further down the list as was the typeface size. This dilemma led to the formation of her own pre-Rockettes chorus line, the highly athletic Gertrude Hoffmann Girls. It was more of an evolution than a formation. They were first mentioned as her all-American ballet troupe of sixteen girls in late 1921 as part of her current traveling show.

|

That group would grow in its fame and repertoire in the early to mid-1920s, becoming the Gertrude Hoffmann Girls in late 1923. Make no mistake that Gertrude was in the middle of it all, although rarely appearing on stage with her bevy of beauties. In addition to this, while Max had formed his own Conservatory of Music in 1923 near their recently acquired Long Island home, Gertrude formed a training school of her own for the dancers. With a noted choreographer and acrobatic instructor, William J. Hermann, she formed the Hoffmann-Herman School that not only instructed the girls in dance, but developed their overall athletic abilities as well. Dancer Ivan Tarasoff also joined the school for a while.

The Gertrude Hoffmann Girls were part of at least two tours of Europe which included appearances at the Hippodrome in London in March 1924 in the show Leap Year, followed by a September date at the Moulin Rouge in Paris for the revue New York-Montmarte. Another tour of both countries was staged in 1925. Both trips included Max in some capacity, most likely as their traveling conductor and music director. In 1925 the troupe played at the Winter Garden Theater in Manhattan in Artists and Models, a Shubert production. Gertrude and her girls danced for two more consecutive seasons at the Winter Garden in 1926 and 1927 in A Night in Paris to a score by fellow female composer Muriel Pollock, and A Night in Spain. They also took Artists and Models and A Night in Paris on the road to Miami in the winter of 1926, complete with Max leading the orchestra. Many of the Hoffmann girls would later be snatched up by other production companies due to their level of talent and training. Given the number of bookings, Gertrude ended up managing multiple dance troupes for various venues, including a unit in Berlin, Germany. She discussed her new endeavor with newspaper reporter George Dritt in July of 1925:

Gertrude Hoffmann isn't so shocking these days, because bare legs have ceased to be a treat. … The name suggested ostracism from Kansas City, denunciation In Cincinnati and Des Moines, censorship in Boston and arrest in New York.

Sandy-haired, slender, cordial Gertrude, however, is no less a dynamic innovator now than in her flashing heyday. Instead of dancing. she is the trainer and impresario of three troupes of dancing girls, now to be seen In London, Paris and New York. And when they step out to win the enthusiastic approval of their beholders, they exhibit with a frankness and abandon which would dazzle the shocked eyes of a dozen years ago.

"These 18 girls don't smoke, drink or dash out on wild parties. They get their fun out of dancing, and turn loose their energy right there. That is why they have so much sparkle. Times have changed, to permit stage dances such as we see now, or to permit the unquestionably artistic tableaux of almost nude figures… I believe that when we reach the degree of frankness when there are no physical taboos between men and women, when they have nothing to conceal from one another, we shall have a better world. We are approaching it. The more a mind is excited at physical revelations, the lower that mind is. I never thought of any body when I was dancing. And if the body is all of me, then I am nothing at all.

"When my girls go out and win praise, some of it comes back to me. I did not stop dancing because I had to, but rather at the peak of [my] success and of a free choice. I consider my girls as material for me to shape, just as I feel that I am putty in the hands of some unseen power which is molding my life. In my dancing and as director, I think I have had the happiest life of any woman on earth."

It is curious, then, that with all this activity, for the 1925 New York census, Gertrude was shown as a housewife, while her husband and a lodger in the home were both listed as musicians.

Meanwhile, Max, Jr., was working the stage as well. Although he had finished his studies at Cornell, his earlier encounter with the stage was too enticing, and he set out attempt a career in show business despite his mother's protestations. While she was in Paris with her troupe, he went around to several casting offices in pursuit of a role. After having appeared in 1922 in a production featuring Nora Bayes at the George M. Cohan theater, He would continue to work his way up through the ranks, including dancing with Ann Pennington in Jack and Jill in 1923, earning his own measure of fame, but not without many public hiccups. Among those was the first of two failed marriages, this one with actress Norma Allison, who was also known as Norma Terris. She had worked with the younger Max in vaudeville before gaining fame in Ziegfeld's production of Showboat in the role of Magnolia, and they co-starred in A Night in Paris as well, making the show a true Hoffmann family affair. But by the late 1920s the couple would be split. He had also been put in charge of one unit of the Gertrude Hoffmann Girls in 1925, which may have been a risky endeavor.

In the spring of 1925, Max and Gertrude ventured to Europe not just for performances, but to celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary, albeit a year early. Upon returning to New York in late May, they held a celebration, and Gertrude commented on the state of their union:

…money, jewels, automobiles and expensive living do not bring happiness or make for a happily married life. Real happiness must come from within. As to growing old—well, if people dwelt not on the subject they could remain young. Pass from one stage of life to the next cheerfully and buoyantly and old age will be long in coming.

Gertrude started dancing again in late 1926, this time as a headliner performing classical dance with her Gertrude Hoffmann Girls taking on other routines. Her last Broadway stage appearances were in the late 1920s.

The Great Depression, the onset of sound films, and the migration of musical talent to Hollywood severely taxed the old school singing and dancing revues on Broadway. The trend was now leaning more towards musicals by Cole Porter, George and Ira Gershwin, as well as material from younger female writers such as Dana Suesse and Kay Swift. The 1930 enumeration, taken in Freeport, Long Island, New York, still listed Max as an orchestra musician, even though he was also continuing to compose and arrange, and Gertrude as a vaudeville dancer, only slightly off the mark. Advertisements from Freeport newspapers of 1929 and 1930 show both of the Hoffmanns teaching music and dance respectively from their Freeport studio.

|

The 1930s are a little vague for information on the couple. Max got some work arranging and writing for movies, which required the occasional stay in Hollywood, but the Hoffmanns still maintained their Long Island home, and Gertrude was working behind the scenes in both New York and Europe. A 1933 notice claimed that she was heading a floor show at the Paramount Grill, a Manhattan supper theater, teaming with French dancer Georges Danilo, and backed by her girls in Talk of the Town. According to a later notice in the New York Evening Post, Georges allegedly missed a cue at their first performance and she "hissed 'Nuts to you' to her foreign partner." The story goes on to claim she found a way to include the phrase in subsequent performances, which Danilo mistook to be a compliment. After a few weeks he was informed by another French employee that it was, in fact, derogatory. At the end of the next performance after a very deep bow he reportedly retorted "Nowtss to you, madame," and quit, thus ending the comeback.

|

In 1935 Gertrude, no longer headlining, traveled with her Continental Revue, advertising 25 people and 18 girls. In the summer of 1936 she staged a ballet for a production of the famous Rudolph Friml operetta Rose Marie in an off-Broadway presentation at Jones Beach Stadium. This was followed by a production of Blossom Time by Sigmund Romberg, based loosely on the life and music of composer Franz Schubert, and staged again by Gertrude at the same venue. Throughout this period there were scattered reports of appearances of the Gertrude Hoffmann Girls throughout the major cities of the US and Europe. They would emerge again near Broadway in late 1938 in a lavish floor show cabaret at the repurposed Paramount Grill, now the Diamond Horseshoe.

After the Hoffmanns temporarily moved west, Gertrude reportedly taught some dance in Hollywood, possibly as the co-director of a dance studio there.

However, they spent part of the mid-1930s touring America and Europe, even as late as 1939, when the growing war in Europe curtailed further appearances. Several biographies cite a short career in films for Gertrude. They are, however, confusing her with a German-born actress, Gertrude Wessen Hoffman, who did have a late in life presence in Hollywood films and television. The Broadway actress appears to have never actually gone before the camera, at least in anything that was released. The Hoffmann's occupations listed in the 1940 census give some clue as to their change in direction, as Gertrude was listed as an opera singer, and Max as a photographic designer. They were living once again in Manhattan in an apartment building with several like-minded creative individuals occupying the same floor.

|

After 1940 little was heard concerning Gertrude or Max, who ostensibly retired. Their son's lifestyle eventually caught up with him, and Max Hoffmann, Jr., died in 1945 in Manhattan at age 43 of a reported stomach ailment. At that same time, it was reported that the senior Max was part of the pit orchestra as a violinist for the ongoing run of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma, the show that largely changed the direction of Broadway pretty far from the institution in which he had started and helped to form. The Hoffmanns permanently relocated to Los Angeles, California, in the early 1950s, taking up residence in West Hollywood in the luxurious Fleur de Lis Apartments. Max died there in May of 1963 at age 89, followed by Gertrude in 1966 at age 83 (despite the fact that the California death index showed a very erroneous birth year of 1877, and her Social Security record showed 1886). Both Max and Gertrude were interred at Grand View Memorial Park and Crematory in Glendale, California.

This article was largely derived from public records and newspaper notices, literally over 1000 of them, contemporary to the lives of the Hoffmanns. Some additional information came from copyright records and IMDB.com, as well as the always reliable reference source, Vaudeville Old and New, by Frank Cullen, Florence Hackman and Donald McNeilly. The NYPL was a good source for photographs and articles on Gertrude.

Compositions

Compositions