|

George Washington Thomas (March 9, 1883 to March 6, 1937) Hersal Thomas (September 9, 1906 to June 2, 1926) | |

Known Compositions (Geo. W. Thomas by default) Known Compositions (Geo. W. Thomas by default) | |

|

1914

It's Hard to Find a Lovin' Man That's True1916

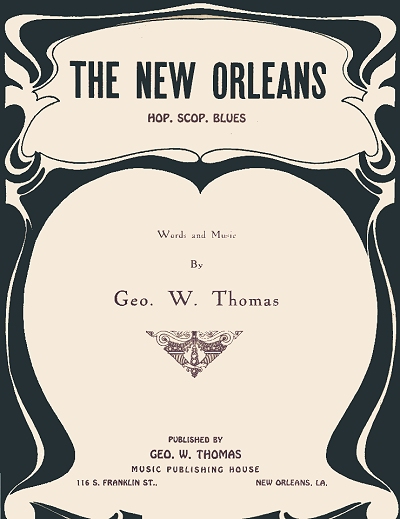

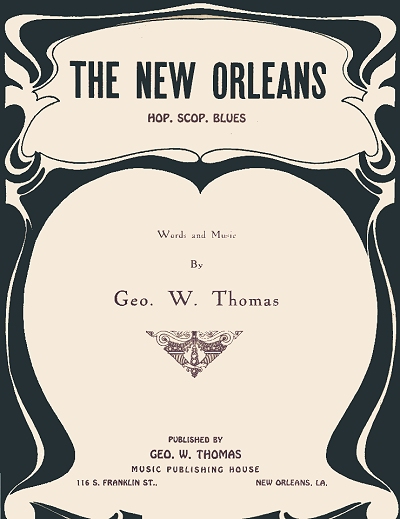

The New Orleans Hop Scop BluesDon't Say Nothing 1917

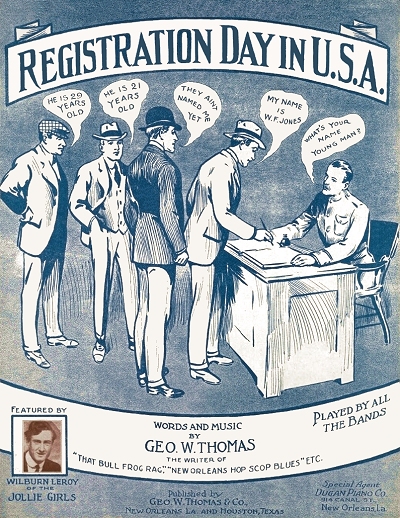

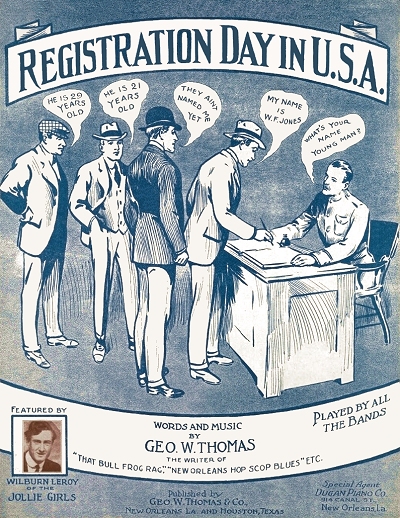

That Bull Frog RagThat Rat-Proof Rag Registration Day in U.S.A. Be Careful, Mr. Strange Man: Rag-Blues If That's Your Company, You're in Right 1919

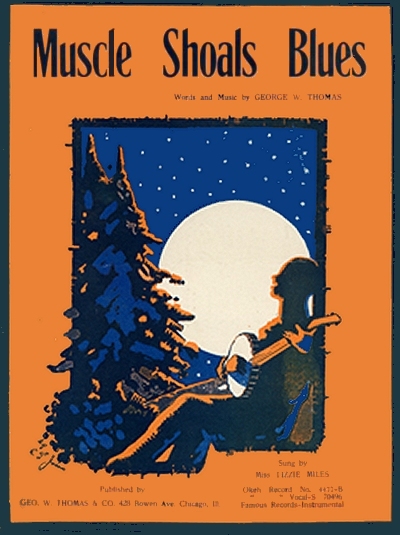

The Houston Blues (A Southern Overture)Muscle Shoals Blues Sweet Baby Doll [1] 1920

Gert Anna Waltz (So Sweet)I'm Goin' to That Jazz Ball, That's All [2] Love Will Live [2] I'll Give You a Chance to Make Good [2] I Can't Be Frisky Without My Whiskey [3] 1921

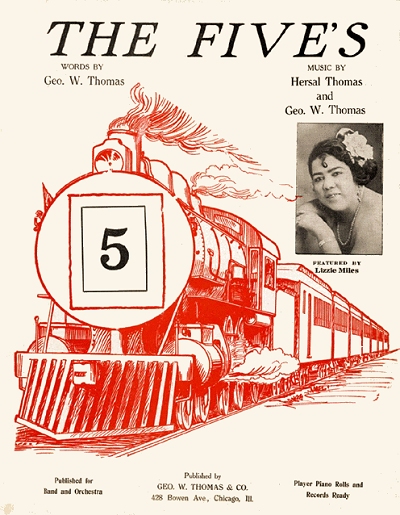

Oh Angel Eyes It's All for YouI Love My Boy Better Than I Do Myself [4] The Fives [4] The World Will Miss You, Roosevelt [5] 1922

At SundownThe Rocks 1923

I've Got a Man of My OwnFeed That Mule Listen to Ma Shorty George Blues [4] Up the Country Blues [6] I Ain't No Sheik, Just Sweet Papa, That's All [7] You Have a Home Somewhere [8] Mammy's Little Brown Rose [9] I've Found a Sweetheart [10] 1924

Wash Woman BluesMorning Dove Blues Caldonia Blues [6] Underworld Blues [6] Trouble Everywhere I Roam [6,11] Sweet Mama, That's All [7] Leaving Me Daddy is Hard to Do [12] 1925

Fish Tail DanceSix Foot By Two I Must Have It Adam and Eve Had the Blues Put It Where I Can Get It I've Stopped My Man |

1925 (Cont.)

I Can't Feel Frisky Without My Liquor [3]Suitcase Blues [11] Hersal Blues [11] The Gambler's Dream [11] Worried Down with the Blues [13] Sunshine Baby [14] 1926

Lonesome Room BluesI Keeps My Kitchen Clean Rest Yo' Hips Gut Struggle Blues I'm Goin' to That OKeh Ball Life is What You Make It Darling Love Me Long Hog's Grunt Sho is Hot They Needed a Piano Player in Heaven, So They Sent for Hersal I Feel Good [11] Dead Drunk Blues [11] A Jealous Woman Like Me [11] Have You Ever Been Down? [11] Bed Room Blues [15] Pig Meat [16] Boot It Boy, Boot It [17] 1927

Gary BluesHave You Ever Been Down? I've Got to Be Loved Block Avenue Blues [18] Harbor Blues [18] 1928

Butcher Shop Blues1936

I Don't Love Nobody But You *

1. w/Wilbur LeRoy

2. w/M. Lauretta Green 3. w/W.E. Hunter 4. w/Hersal Thomas 5. w/Adolph Atkins 6. w/Sippie Wallace 7. w/Tom Scott 8. w/Billy Jahncke 9. w/E. Goins Iseli 10. w/P. Rudd 11. by Hersal Thomas 12. w/Vera Hinton 13. w/Hociel Thomas 14. w/Rose McMahon 15. w/Ethel Bynum 16. w/Lettie Williams 17. w/Constance Griswold 18. w/Addie Rodgers * Unpublished |

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |

|

1923

The Rocks [1]Shorty George Blues [1,2] Up the Country Blues [1,2] Houston Blues [1,2] I Got a Man of My Own [1,2] 1925

Suitcase Blues [3]Morning Dove Blues [3,4,5] Devil Dance Blues [3,4,5] Every Dog Has His Day [3,4,5] Hersal Blues [3] Worried Down with the Blues [3,6] Fish Tail Dance [3,6] Wash Woman Blues [3,7] Morning Dove Blues [3,7] Being Down Don't Worry Me [3,4,8] Advice Blues [3,4,9] Murdrer's Gonna Be My Crime [3,4] The Man I Love [3,4] Gambler's Dream [3] Sunshine Baby [3] Adam and Eve Had the Blues [3] Put It Where I Can Get It [3] Wash Woman's Blues [3] I've Stopped My Man [3] 1926

Deep Water Blues [3,6,9]G'Wan I Told You [3,6,9] Listen to Ma [3,6,9] Lonesome Hours [3,6,9] A Jealous Woman Like Me [3,4,9] Special Delivery Blues [3,4,9] Jack o' Diamonds Blues [3,4,9] The Mail Train Blues [3,4,9] I Feel Good [3,4,9] A Man for Every Day in the Week [3,4,9] Kitchen Blues [3,10] Bed Room Blues [1,11] * Rest Yo Hips [1,11] * 1928

Harbor Blues [12]You Just Keep Can't Keep a Good Woman Down [1,12] Butcher Shop Blues [12] Dead Drunk Blues [12] 1929

Fast Stuff Blues [1]Don't Kill Him In Here [1]

1. George W. Thomas [or as Clay Custer]

2. w/Tiny Franklin 3. Hersal Thomas 4. w/Sippie [Thomas] Wallace 5. w/Joseph "King" Oliver [tpt] 6. w/Hociel Thomas 7. w/Thomas' Muscle Shoal Devils |

Matrix and Recording/Release Date

[OKeh S71290] 02/??/1923[Gennett 11696] 12/20/1923 [Gennett 11698] 12/20/1923 [Gennett 11700] 12/20/1923 [Gennett 11701] 12/20/1923 [OKeh 8964] 02/24/1925 [OKeh 8965] 02/24/1925 [OKeh 8966] 02/24/1925 [OKeh 9166] 05/??/1925 [OKeh 9167] 05/??/1925 [OKeh 9168] 05/??/1925 [OKeh 9169] 05/??/1925 [OKeh 9170] 05/??/1925 [OKeh 73557] 08/20/1925 [OKeh 73558] 08/20/1925 [OKeh 73566] 08/25/1925 [OKeh 73567] 08/25/1925 [OKeh 9471] 11/11/1925 [OKeh 9472] 11/11/1925 [OKeh 9473] 11/11/1925 [OKeh 9474] 11/11/1925 [OKeh 9475] 11/11/1925 [OKeh 9476] 11/11/1925 [OKeh 9520] 02/24/1926 [OKeh 9521] 02/24/1926 [OKeh 9522] 02/24/1926 [OKeh 9546] 03/01/1926 [OKeh 9547] 03/01/1926 [OKeh 9548] 03/01/1926 [OKeh 9559] 03/03/1926 [OKeh 9560] 03/03/1926 [OKeh 9561] 03/03/1926 [OKeh 9570] 03/04/1926 [Columbia 142440] 07/14/1926 [Columbia 142441] 07/14/1926 [Gennett 13713] 05/03/1928 [Gennett 13716] 05/03/1928 [Gennett 13718] 05/03/1928 [Paramount L0018] 11/??/1929

8. Rudolph Jackson [sax]

9. w/Louis Armstrong [tpt] 10. w/Lillian Miller 11. Ethel Bynum 12. Lillian Miller * Unissued |

George Washington Thomas, named after both his father and the man known as the "Father of Our Country," was himself a father of, or at least major contributor to, the piano style that would evolve into boogie-woogie. His brother Hersal also became a big component of that movement before his life was tragically cut short. There are many details of their lives that remain a mystery, in part because of lack of proper research in the past, and in part due to the way in which many black people were improperly counted or documented, or just plain ignored, during a difficult period in American history. As much pertinent information as is now known and can be confirmed concerning George and Hersal has been included here, with anything that is speculation or simply unknown clarified as such. Even with the lack of information, their collective stories are an important part of the barrelhouse child of ragtime, founded in southern Texas and Louisiana, and evolved in Chicago.

George was one of as many as thirteen known children born to George Washington Thomas and Fannie Bradley, of which only eight survived to 1900. The others included Florence (6/1880), Josephine (6/1886), Callie (4/1888), Lucille (7/1891), Willie (10/1894), John H. (6/1896), Beulah "Sippie" (11/1/1898), Myrtle (1902), and Hersal (9/9/1906). Some accounts of Hersal's life give him a 1909 or 1910 birth, but the 1910 enumeration proves otherwise.

George Thomas, Sr., was born in Alabama near the beginning of the Civil War, so possibly born into slavery. Fannie was born in Arkansas shortly after the end of the war, and while her mother was from Virginia, her father had been one of the last batch of slaves imported directly from Africa in the 1830s. They were living in Plum Bayou in central Arkansas when most of their children, including George, Jr., were born, but had relocated to southern Texas by 1898 when Beulah came into the world. The 1900 and 1910 enumerations found the family living in the greater Houston area. While the elder George was a day laborer, taking on whatever work came along in 1900, Fannie was contracting out as a seamstress, and even George, Jr., was listed as a salesman, but the specific job description is unclear on the census. While it has also been written that George, Sr., was a deacon at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Houston, this is not fully substantiated in any directory listings or census records, so if he was it was a part time job, and no evidence was found that he was ordained. As there are multiple stories about the Thomas children participating in the church music programs in some capacity, his involvement with Shiloh leadership is not in question.

her father had been one of the last batch of slaves imported directly from Africa in the 1830s. They were living in Plum Bayou in central Arkansas when most of their children, including George, Jr., were born, but had relocated to southern Texas by 1898 when Beulah came into the world. The 1900 and 1910 enumerations found the family living in the greater Houston area. While the elder George was a day laborer, taking on whatever work came along in 1900, Fannie was contracting out as a seamstress, and even George, Jr., was listed as a salesman, but the specific job description is unclear on the census. While it has also been written that George, Sr., was a deacon at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Houston, this is not fully substantiated in any directory listings or census records, so if he was it was a part time job, and no evidence was found that he was ordained. As there are multiple stories about the Thomas children participating in the church music programs in some capacity, his involvement with Shiloh leadership is not in question.

her father had been one of the last batch of slaves imported directly from Africa in the 1830s. They were living in Plum Bayou in central Arkansas when most of their children, including George, Jr., were born, but had relocated to southern Texas by 1898 when Beulah came into the world. The 1900 and 1910 enumerations found the family living in the greater Houston area. While the elder George was a day laborer, taking on whatever work came along in 1900, Fannie was contracting out as a seamstress, and even George, Jr., was listed as a salesman, but the specific job description is unclear on the census. While it has also been written that George, Sr., was a deacon at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Houston, this is not fully substantiated in any directory listings or census records, so if he was it was a part time job, and no evidence was found that he was ordained. As there are multiple stories about the Thomas children participating in the church music programs in some capacity, his involvement with Shiloh leadership is not in question.

her father had been one of the last batch of slaves imported directly from Africa in the 1830s. They were living in Plum Bayou in central Arkansas when most of their children, including George, Jr., were born, but had relocated to southern Texas by 1898 when Beulah came into the world. The 1900 and 1910 enumerations found the family living in the greater Houston area. While the elder George was a day laborer, taking on whatever work came along in 1900, Fannie was contracting out as a seamstress, and even George, Jr., was listed as a salesman, but the specific job description is unclear on the census. While it has also been written that George, Sr., was a deacon at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Houston, this is not fully substantiated in any directory listings or census records, so if he was it was a part time job, and no evidence was found that he was ordained. As there are multiple stories about the Thomas children participating in the church music programs in some capacity, his involvement with Shiloh leadership is not in question.It was originally at school and church where George, and later Hersal and Beulah, found their passion for music. George would soon take up not only the piano, but cornet and saxophone as well. However, it was in the traveling tent shows featuring playing and singing styles not heard in church that the the Thomas siblings found their direction. George heard and then played ragtime and blues. Beulah remembered slipping out through her bedroom window many evenings to sneak into tents where she heard some of the earliest incarnations of the blues and popular songs. This was not well received by the parents at first, given that ragtime was "the devil's music," but it seemed there was little they could do to stop their children from learning that new music. Around 1903 to 1904, George was married to Octavia Malone. They had one child together, Hociel, born on July 10, 1904. Records are unclear on what happened, but Octavia died at some point between 1905 and 1907. The 1910 census showed George, now working as a musician, as widowed, and Hociel listed as one of his siblings. She was ultimately raised by both her grandmother Fannie and aunt Beulah, the latter who would play a big role in her life.

One of the up and coming musicians making the rounds in Houston in the early 1910s was Clarence Williams as part of the Benbow Stock Company. He would later own a publishing empire and amass a large collection of compositions, albeit not all of them actually his. He and George played in many of the same Texas theaters. Initially, even though Clarence was a decade younger than George, his talent was such that he would play in the pit band, while George was the pianist for the silent films, as well as an intermission performer. They became fast friends for a time, and George followed Clarence to New Orleans around 1913 (some accounts claim 1914). Williams had already spent considerable time and had some roots in town, and was soon engaged to manage and play at a succession of nightclubs. Around 1915 Clarence and George formed a publishing company which initially released Clarence's work. The pair would plug songs that they sold from either a store front or door-to-door. Hersal would soon follow his older brother to New Orleans, and while residing with him also learned the piano very quickly, soon excelling in his craft.

He and George played in many of the same Texas theaters. Initially, even though Clarence was a decade younger than George, his talent was such that he would play in the pit band, while George was the pianist for the silent films, as well as an intermission performer. They became fast friends for a time, and George followed Clarence to New Orleans around 1913 (some accounts claim 1914). Williams had already spent considerable time and had some roots in town, and was soon engaged to manage and play at a succession of nightclubs. Around 1915 Clarence and George formed a publishing company which initially released Clarence's work. The pair would plug songs that they sold from either a store front or door-to-door. Hersal would soon follow his older brother to New Orleans, and while residing with him also learned the piano very quickly, soon excelling in his craft.

He and George played in many of the same Texas theaters. Initially, even though Clarence was a decade younger than George, his talent was such that he would play in the pit band, while George was the pianist for the silent films, as well as an intermission performer. They became fast friends for a time, and George followed Clarence to New Orleans around 1913 (some accounts claim 1914). Williams had already spent considerable time and had some roots in town, and was soon engaged to manage and play at a succession of nightclubs. Around 1915 Clarence and George formed a publishing company which initially released Clarence's work. The pair would plug songs that they sold from either a store front or door-to-door. Hersal would soon follow his older brother to New Orleans, and while residing with him also learned the piano very quickly, soon excelling in his craft.

He and George played in many of the same Texas theaters. Initially, even though Clarence was a decade younger than George, his talent was such that he would play in the pit band, while George was the pianist for the silent films, as well as an intermission performer. They became fast friends for a time, and George followed Clarence to New Orleans around 1913 (some accounts claim 1914). Williams had already spent considerable time and had some roots in town, and was soon engaged to manage and play at a succession of nightclubs. Around 1915 Clarence and George formed a publishing company which initially released Clarence's work. The pair would plug songs that they sold from either a store front or door-to-door. Hersal would soon follow his older brother to New Orleans, and while residing with him also learned the piano very quickly, soon excelling in his craft.In 1916, George issued his first rendition of The New Orleans Hop Scop Blues. It was part of the breed of twelve-bar blues that had been in print for several years now. However, in the third section, an articulated left hand was notated using grace notes for the lower tone. This created a pseudo boogie bass. Some music historians consider this to be the origins of the boogie sound, and ultimately boogie-woogie. While George did not invent this paradigm, and had possibly heard it some years prior in a tent show, he was able to notate a version of it. However, this strain had also been making the rounds up north in Saint Louis, Missouri. In 1915, publisher John Stark issued Weary Blues by the gifted composer Artie Matthews. Both of the first two sections are twelve-bar blues, and the first contains a pattern that would later find its way in a modified form into Pine Top Smith's famous Boogie-Woogie. The second section contains a fully articulated bass line that, short of the flatted seventh on the tonic, is a full-fledged boogie bass. So while Thomas was early in the game as far as getting the style into print, he still a year behind. There is some irony that Stark, the man who issued the first classic piano rags, may have also published the first boogie piano piece in print.

While New Orleans Hop Scop Blues was not a hit initially, it did establish George as both a publisher and composer. As a player with a strong left hand, he soon earned the nickname "Gut Bucket George," for his pounding bass. He issued a couple of unique rags in 1917 as well as a number of songs with his own lyrics. Hersal learned these pieces and many more, and started playing them with other New Orleans musicians, including Joseph "King" Oliver and his protégé Louis Armstrong. Even in his early teens he was highly regarded for his acumen. Oliver would soon move to Chicago, Illinois, part of a migration of NOLA musicians that would make their way up to the windy city after World War I had ended. George remained in New Orleans for a while, issuing more tunes, and working more with his younger sister Beulah. She was now part of the household as well. Beulah and Hersal spent time both in Houston and New Orleans during this period. On his September 12, 1918, draft record, George noted that he was working for a music publishing company, and that his reason for a deferment was "one half thumb missing on right hand to first joint." This may explain his preference to compose and run the company rather than to perform, although he did quite a bit of the latter. The 1920 enumeration taken in New Orleans showed him working as a musician and lodging with Alice Jackson and her family. By this time, Fannie, who had been widowed around two and a half years prior, was running a boarding house in Houston. Hersal was staying with her at the time the record was taken.

This may explain his preference to compose and run the company rather than to perform, although he did quite a bit of the latter. The 1920 enumeration taken in New Orleans showed him working as a musician and lodging with Alice Jackson and her family. By this time, Fannie, who had been widowed around two and a half years prior, was running a boarding house in Houston. Hersal was staying with her at the time the record was taken.

This may explain his preference to compose and run the company rather than to perform, although he did quite a bit of the latter. The 1920 enumeration taken in New Orleans showed him working as a musician and lodging with Alice Jackson and her family. By this time, Fannie, who had been widowed around two and a half years prior, was running a boarding house in Houston. Hersal was staying with her at the time the record was taken.

This may explain his preference to compose and run the company rather than to perform, although he did quite a bit of the latter. The 1920 enumeration taken in New Orleans showed him working as a musician and lodging with Alice Jackson and her family. By this time, Fannie, who had been widowed around two and a half years prior, was running a boarding house in Houston. Hersal was staying with her at the time the record was taken.Among the standout tunes that George had composed while in New Orleans was his Muscle Shoals Blues, named for a treacherous stretch of shallows and rapids on the Tennessee River in northern Alabama near Chattanooga, Tennessee. It contained several patterns and melodic lines that were gathered in a sense, much in the way W.C. Handy had been doing, then modified by George and put into print. This would become a popular blues for many years. It was apparently only copyrighted in New Orleands, but not published until he moved to Chicago in 1920. It was one of the first pieces recorded by a young Thomas "Fats" Waller in 1922. George also started writing tunes with Hersal, now all of fourteen in 1920, and performing them with Beulah.

Beulah Thomas had gone to New Orleans around 1913, and ended up marrying Frank Seals while all of sixteen. The marriage was short-lived, and gave Beulah a solid foundation for her blues singing and lyrics. She tried to break into a traveling tent show and ended up being an assistant to a snake dancer in a reptile show. However, her unique singing skills were soon discovered, and before she was twenty she became known at the "Texas Nightingale." During the late 1910s she met and married Matthew Wallace who was a gentleman, but also a gambler. He tried to participate with her in the music business, helping to write some of her songs, and even acting as her manager and announcer. However, due to his gambling issues, this marriage also ultimately failed in the late 1920s, and Beulah had more material to work with for her sometimes visceral and raww lyrics. Even before then, she had a new stage name, taking her second husband's last name and combining it with a derivative of the state she was sometimes identified with, Mississippi. By 1920 she was "Sippie" Wallace, and retained that name for the rest of her career. She had also been a surrogate mother to Hersal while they were in New Orleans, and to Hociel as well. To her young niece she became a mentor, and taught her all she knew about singing the blues.

Around 1921, George followed many of his peers to Chicago, bringing his publishing company - now wholly his - with him. He reissued some of his previous numbers under his Chicago imprint, and started taking on compositions by other writers. He also played with some local groups and occasionally as a soloist or accompanist for other singers, including his sister who joined him some time later. Hersal also moved in with his big brother in 1922. By this time, he had become a competent and forceful pianist with a definitive barrelhouse left hand and a feeling for the blues as well. At just 16, Hersal contributed to a piece that became a standard for Chicago barrelhouse pianists in short order.

George had already composed The Rocks which had a boogie bass line with blues riffs in multi-part form. With Hersal he composed The Fives, which many music historians believe is the first published boogie-woogie with a boogie bass line throughout. While it may not have been the first one passed around and played frequently, that it was the first in print is an arguably valid claim. As with some earlier pieces, including Hiawatha (1901) by Charles Daniels, George noted that he based the left hand on the rhythm of the trains, and included other facets of rail travel. Specifically, he was referring to a journey from Chicago to San Francisco, with the fives being both the arrival time, and as noted in George's lyrics, the train number:

While it may not have been the first one passed around and played frequently, that it was the first in print is an arguably valid claim. As with some earlier pieces, including Hiawatha (1901) by Charles Daniels, George noted that he based the left hand on the rhythm of the trains, and included other facets of rail travel. Specifically, he was referring to a journey from Chicago to San Francisco, with the fives being both the arrival time, and as noted in George's lyrics, the train number:

While it may not have been the first one passed around and played frequently, that it was the first in print is an arguably valid claim. As with some earlier pieces, including Hiawatha (1901) by Charles Daniels, George noted that he based the left hand on the rhythm of the trains, and included other facets of rail travel. Specifically, he was referring to a journey from Chicago to San Francisco, with the fives being both the arrival time, and as noted in George's lyrics, the train number:

While it may not have been the first one passed around and played frequently, that it was the first in print is an arguably valid claim. As with some earlier pieces, including Hiawatha (1901) by Charles Daniels, George noted that he based the left hand on the rhythm of the trains, and included other facets of rail travel. Specifically, he was referring to a journey from Chicago to San Francisco, with the fives being both the arrival time, and as noted in George's lyrics, the train number:Here come number 5 she makes a mile a minute, Gee she run so fast this morning she broke the limit.

Oh! goodness how that west bound what I mean that West bound train does run.

Engineer looked at his watch and said if I'm alive, We'll be in Frisco tomorrow morn sure at Five.

Oh! goodness gee I've got the Frisco I mean the Frisco evening Fives.

It was this piece that helped to inspire a generation of boogie-woogie pianists, including Clarence 'Pine Top' Smith, Meade 'Lux' Lewis,, Pete Johnson, Jimmy Yancey and Albert Ammons among others. Hersal was the premiere performer of the piece, for which he had co-written some of the musical licks. Between that and other pieces in his catalog, George was starting to see his business thrive a bit more, and as 1923 rolled around he found his compositions making the round on records and piano rolls. Pretty soon he allegedly recorded The Rocks for OKeh records using the pseudonym Clay Custer for some unknown reason. However, his direct involvement in this recording has been challenged, and it may have been Hersal or even composer/performer Harry Jentes who provided the performance. Late in the year George traveled to Richmond, Indiana, to accompany Tiny Franklin for several tracks on the Gennett label, four of which were ultimately released.

Sippie was also gaining traction in Chicago, and had toured in 1923 and 1924 on the T.O.B.A. (Theater Owner's Booking Association) circuit, creating an audience as well. Hersal often went along as her accompanist, as did Hociel as a sort of understudy. George worked in some capacity with the Kimball Music Company, and also had his own performing group, the Muscle Shoals Devils, who according to a Music Trade Review notice in the December 9, 1922, issue, had also made some recordings of his pieces. (The recordings mentioned were evidently not released.) George received fair treatment within the music trades as well, as they published color-blind articles about his success, such as this one from the Music Trade Review of January 26, 1924:

Why George W. Thomas Music Co.'s Music Sells Readily Explained by Head of Firm.

"We have a very gratifying number of hits on our list because we sensed what the music buying public wanted and provided it. It is something that any business man can understand," said George W. Thomas, head of the George W. Thomas Music Co., 428 Bowen avenue, Chicago, this week. Mr. Thomas understands the music market. He is an accomplished musician and his orchestra, The Nine Muscle Shoals Devils, has been a theater feature in many cities in the country for the past year. Properly gauging the market, Mr. Thomas two years ago brought out "Muscle Shoals Blues," his first number. It won immediate success because it was "different." "The world wants dancing music, and, tunefulness apart, wants something not reminiscent of hundreds of dances that have gone before," said Mr. Thomas. "It is a waste of energy for the composer or publisher to plagiarize a winner. The music buying public is too wise today. And people who love to dance, even if they do not play music, are quick to appreciate novelty in melody and theme in a new song."

"I Ain't No Sheik," the second of the Geo. W. Thomas Music Co.'s productions, repeated the successes of "Muscle Shoals Blues." It has the swing and go that made the dancing folk want it. After that the production of a number by the Chicago house quickly resulted in big sales. Bands [and] orchestras are eager to play a Thomas number at the earliest and dealers find it good business to stock and feature it.

In 1925 and into 1926 both George and Hersal did a number of recording dates with OKeh.

On some sessions Hersal accompanied Sippie, and he also played behind his niece Hociel. Although Hersal had written Gambler's Dream about Sippie's second husband, it was Hociel who took the reins when it was recorded and gave it a deep and mournful take of her own. Virtually all of their sessions were for OKeh Records in their Chicago studio, and all were done prior to the acquisition of the company by Columbia Records in mid-1926. Many enduring unpublished hits were committed to disc, including Hersal's Suitcase Blues, referring to the rigors of travel. It and Wash Woman Blues have remained in the standard boogie-woogie repertoire since they were introduced. Some of the sessions included Oliver in 1925, and then Armstrong in 1925 and 1926 with a variation on his Hot Five ensemble, adding in clarinetist Johnny Dodds and banjoist Jonny St. Cyr. Many of those tunes were written by one or more of the siblings. All seemed to be going well for the Thomas brothers and their family.

|

|

But there would soon be tragedy within the family as well. The Thomas's sister Willie (sometimes seen as Lillie) died in late 1925. She had been partly responsible for putting the musical bug in Sippie, and always encouraged her brothers to excel as well. On June 2, 1926, [as per Michigan death records and a mention in the Chicago Defender on June 12, debunking the July 3 date commonly given] Hersal was performing at Penny's Pleasure Palace in Detroit, Michigan when he was suddenly taken ill. It is unclear what happened that evening, but most reports point to ptomaine poisoning from the food, possibly pork and beans, as the probable cause of the malady. He died just a couple of months short of his 20th birthday, and was shipped back to Houston for burial. The Defender article, as noted by music historian/performer Bob Pinsker, mentioned a wife as well, but no record has been found to indicate that Hersal was ever legally married, so this may have been a speculation by or misinformation given to the reporter. Hersal's sudden death hit both Sippie and George very hard. George briefly continued some of his musical activity for a time, including some recordings, and a surge of compositions throughout the remainder of 1926. One of them was a moving tribute to his late brother. However, his output eventually dropped off as the late 1920s approached.

After nearly two years of relative silence other than a few copyrights and publications, George cut a pair of sides with Lillian Miller for Gennett in 1928, then for Paramount records in 1929. Sippie had been recording again as well. Fairly soon, the onset of the Great Depression would also place some demand on blues singers, particularly on disc and on the radio, so this was encouraging at the very least. However, George would not be not be so active during that time. While most traditional sources have no firm consensus on how or even when he died, the most common story was recounted in later years by Sippie to her manager Ron Harwood, so it is a second hand story at best. He was told that George "was running after a departing street car in the winter and slipped on the ice while reaching for the grab bar and broke his back. While recovering at home, there was a fire and he fell while trying to make it down the stairs and died in the hospital." The latter part actually turned out to be accurate, so it is unclear if there was ever a streetcar debacle. His official record of death in Chicago from March 6th, 1937, three days short of his 54th birthday, shows that he survived several years longer than virtually all previous accounts have noted. The cause was a broken back from falling down a flight of steps. According to Pinsker, who had also uncovered this information, the weather in Chicago around that time did not involve freezing temperatures or adverse conditions, casting doubt on his having slipped on ice, so the fire theory may still be in play. It also did not mention if the steps were inside or outside. The main question that this death date adjustment brings up is what was George doing for the seven years prior to this? The death certificate, with information provided by a neighbor who knew only the basics about George, showed him as a "music writer," but copyright records of anything new from his hand other than one 1936 unpublished copyright were not readily found for the period of 1929 to 1935 (two 1929 copyright transfers were of earlier works). Of some interest also is that he was shown as having been divorced, but a search of marriage records from 1920 to 1935 turned up nothing that matched, so that may have been another misunderstanding by the neighbor. George W. Thomas was laid to rest appropriately enough in Restvale Cemetery in nearby Alsip, Illinois.

Both Sippie and Hociel went on as blues singers, with Sippie getting the most notice in that field. By 1929 she was based in Detroit, Michigan, where Hersal had died. As it was hard for Sippie to get steady work during the Depression in what was becoming a crowded niche field, she pulled back from blues for a while, working as a church organist, choir director and worship singer for the Leland Baptist Church, while still doing occasional gigs. However, Wallace came back to the forefront as a blues singer in the 1960s, working on several occasions with Louis Armstrong, and eventually warranting a Grammy™ nomination in 1983. She continued to work until she suffered a stroke in the spring of 1986 after a performance. Beulah Sippie Wallace died on her 88th birthday later in the year.

Hociel toured for a time with Louis Armstrong, then retired soon after Hersal's death. She tried to resurrect her career in the mid-1940s, but after a vicious fight in 1950 with one of her other sisters left that sister dead and Hociel partially blinded, she retired and died soon after in 1952 of heart failure in Oakland, California.

As for the legacy of Hersal and George, they are remembered as pioneers in the field of boogie-woogie piano, particularly in context with their Texas heritage, even though George was born in Arkansas, and their recordings are still available today on CDs or through downloads. Most contemporary boogie-woogie artists, including Bill Westcott, Bob Seeley, Carl "Sonny" Leyland and Neville Dickie have at least some Thomas brothers tunes in their repertoire, keeping that rolling beat alive and kicking.

Most of the material for this book was collected from Federal and municipal government sources, newspaper items, discographies, copyright records, and information conveyed over time by Sippie Wallace in various sources. Some corrected information on the dates of death of both brothers was provided by California performer and researcher Robert Pinsker, which helped to debunk some of the soft information on this topic given by Sippie or others with faulty memories. His input is invaluable in this case, and helps to solve some questions that have long been unanswered. Bob's fine article on George W. Thomas can be found at sandiegoragtime.com. In spite of a careful search through multiple sources, a definitive cause of death beyond potmaine poisoning was not found for Hersal, so the information here which has been commonly distributed is accepted as plausible, even if not perfectly accurate. It has been speculated that some musicians were poisoned by jealous rivals in Detroit, Chicago, and other locales, and while this speculation has also been applied in Hersal's case, it cannot be substantiated and is therefore dismissed as hearsay, and relatively unlikely. For more information on Sippie Wallace, there are several fine books on women who sang the blues from the 1920s to 1950s, and she is present in pretty much all of them, as well as Hociel Thomas in most of them.