Homer H. Denney was part of the group of Ohio Valley composers that produced compositions steeped with folk heritage. He would consider himself as much a river man as a musician right to the end, and history spans both ragtime and the last segment of the riverboat era in Ohio. Homer was born in Gallipolis, Ohio, on the border with West Virginia, to Zachariah A. Denney and Emma Pauley. He also had a brother, Raymond Denney, born in January 1887.

Homer was born in Gallipolis, Ohio, on the border with West Virginia, to Zachariah A. Denney and Emma Pauley. He also had a brother, Raymond Denney, born in January 1887.

Homer was born in Gallipolis, Ohio, on the border with West Virginia, to Zachariah A. Denney and Emma Pauley. He also had a brother, Raymond Denney, born in January 1887.

Homer was born in Gallipolis, Ohio, on the border with West Virginia, to Zachariah A. Denney and Emma Pauley. He also had a brother, Raymond Denney, born in January 1887.Zachariah was listed as a house painter in 1900 and 1910. He was one of ten children of respected Gallipolis butcher and volunteer fireman Zachariah Denney Sr. and Mary M. Cavin, residents of Ohio since the early 19th century. By 1900 the family had moved to Cincinnati, where Homer would spend most of his life. According to his family, one of his passions became bicycle racing, and he won several races over the years. But the two most enduring interests that would permeate his life were music and boats. That he was able to combine these was a true blessing.

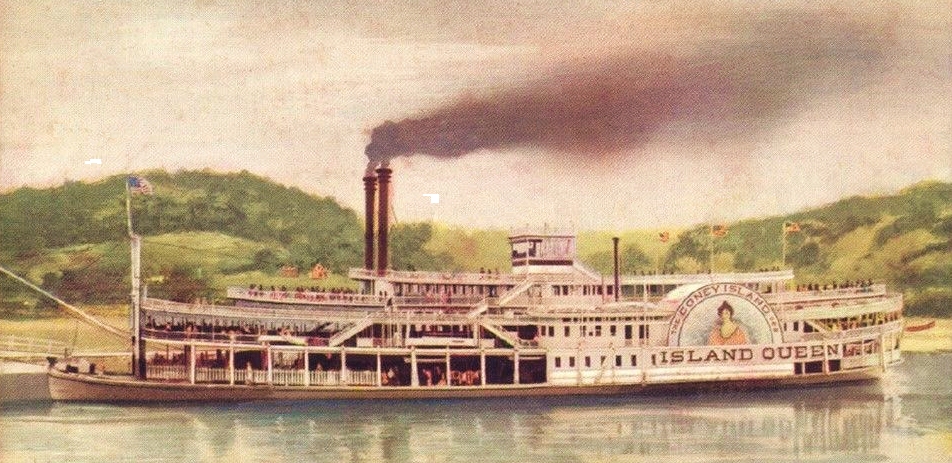

As a child Homer took piano lessons and played for dances and parties. In the 1900 enumeration, at age 14, he was listed as a messenger. The lad had a fascination with the calliope and wanted very much to be given an opportunity to play one to prove himself. That opportunity presented itself when the player on the original paddlewheel steamer Island Queen fell ill in 1901. He did well on his first outing for a 16-year-old, and when the other player died shortly thereafter, he was offered the position.

He did well on his first outing for a 16-year-old, and when the other player died shortly thereafter, he was offered the position.

He did well on his first outing for a 16-year-old, and when the other player died shortly thereafter, he was offered the position.

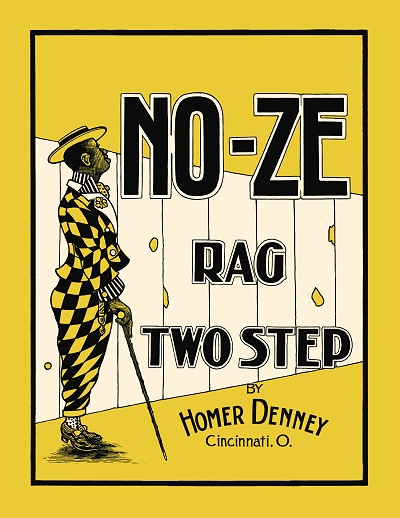

He did well on his first outing for a 16-year-old, and when the other player died shortly thereafter, he was offered the position.The first verified fix on Denney as a musician is in 1905 when he self-published his first rag, No-Ze, in Cincinnati. By this time, he was already making a name for himself as a calliope player on the Ohio River. His next piece, Coney Island Girl, refers to the Coney Island in the river at Cincinnati, which has had a long history of amusement parks and recreation since the late 19th century. The boat he spent most of his life working for during its first and second incarnations was the Island Queen. Built on the frame of the former Saint Joseph, the first Island Queen was launched in 1896, and improved in 1905. It held as many as 3,000 passengers, usually in service from the city to the amusement island, but sometimes for special excursions as far south as New Orleans during Mardi Gras. As a result of his employment on the ship, many of Denney's pieces were fairly simple yet innovative, making the best possible use of the limited yet demanding calliope keyboard. He also played piano on the ship in the interior dining area. His next composition, Water Queen was likely dedicated to the Island Queen.

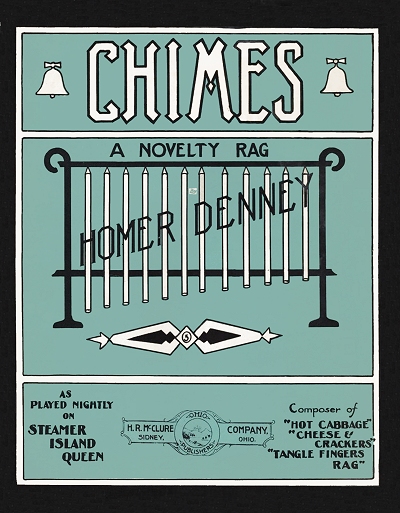

Homer was married in early 1906 to Bertha Kraft, and on December 28, 1908, their daughter June Deloris was born. One other child had not survived infancy. By 1907 Homer was starting to make somewhat of a name for himself on the river. That same year, one of Homer's more notable rags, Hot Cabbage, was self-published. He followed this up with the popular Cheese and Crackers. Both of these first-rate works were soon picked up by larger publishers. The same was the case with Chimes, perhaps his best-known rag.

It was inspired by the sight of a group of children at a dock and their excitement at the approach of the Island Queen and the sound of Homer's calliope. By 1910 he listed in both the Federal Census and the Ohio Miracord as a steam boat musician living in Cincinnati. His partially obscured age appears to be 20, but it is likely 24. Homer's widowed mother-in-law, Jennie Kraft, was living with the couple by then, as she would through most of her remaining life.

|

Denney did not meet the same success with his next two rags, Monograms and Ham Bones as he had with Chimes. He also co-wrote an ethnic Jewish piece with comedian Ben Rafalo, but it had a limited shelf life. Ironically, one of the pieces most associated with him was Caliope Rag, actually composed by brothers Sylvester and Charles Hartlaub. Homer was known for his nightly performances of this popular piece, and its wide distribution helped make him somewhat famous. Another such piece was The Queen Rag by Floyd Willis.

In an article written later in his life, he clearly explained that it took more than musical acumen to play his chosen instrument:

A steam calliope is very hard to play. It takes strength to press the keys down. A calliope is a set of thirty-two [sometimes more] whistles tuned to a definite pitch. The ranges is from 'C' to 'F', a little over two octaves. There are 200 pounds of steam coming up through the valve which makes eight pounds of pressure on each note. Every finger has to push down eight pounds of steam to make a sound, and to keep the note on pitch the finger has to hold down the note with that eight pounds of steam pressure, otherwise it will be off pitch when even slightly released. Everyone cannot sustain notes against the steam pressure which accounts for its sound out of tune. I had strong fingers and it was not hard for me.

The Island Queen was a well-known ship, running between Cincinnati and Coney Island, with various entertainers on board, but Denney reportedly being the star. Given the sheer decibel volume of a typically steam calliope, he was hard to avoid in any event.

The ship carried some 4,000 passengers at a time, and was covered with around 7,000 electric lights. For longer excursions there was a 20,000 square foot dance floor, for which Denney often led the ship's dance orchestra. Homer continued to work on it for some time, and in an additional capacity in 1914 as the tuner of new steam calliopes built at the Thomas J. Nichol factory, most of them built by Nichol himself. But either Homer's personal fortunes started to sag or that of the steamer's ownership, affected by World War I in part.

|

By 1917 Denney had long since ceased composing, and his frequency on the ship is uncertain. He was instead primarily employed at the Universal Car Company as an inspector and motor tester, as listed on his draft record, and shows the same position as of the 1920 enumeration. On April 27, 1922, the roof and some of the decks collapsed on the Island Queen, putting it out of commission for a few months. After it was repaired, on November 4, 1922, the Island Queen burned along with other ships at the Cincinnati docks. As it turns out, the backup employment option was a good plan for the Denney family. During the gap and well beyond, Denney continued to play a Tangley air pressure calliope in the Shrine Circus, being an active member of the Shriners. In the interim, the G.W. Hill was pressed into service, and Denney managed to get some work on it until the new ship was ready. He also kept busy with his own small orchestra that played both in town and later on the replacement sidewheeler.

The new oil powered steamer Island Queen built on a steel hull was launched in 1925, and with it, a resurrection of Denney's career as a dedicated calliope player. He was able to salvage the original calliope after the fire 1922, as it had miraculously stayed above the water line. Homer rebuilt it so it could be sold to the new ship.

His newly resurrected instrument was made on a substantial iron frame, and the echoes of nostalgia for riverboats made them popular again, in part due to Edna Furber's novel Showboat, soon to become a Jerome Kern stage musical. Denney rode this wave for many more years, right on through the Great Depression. The 1930 census lists him as a musician on the ship. As of the late 1930s he was an employee of the waterworks for City of Norwood where the family had moved years before.

|

Around that same time, after a bout with pneumonia, doctors had advised him to move out west to boost his survival chances. Denney responded by staying in Ohio, but taking a hiatus from the ship, and he took up farming for a while. He bought his own tractor and used it not only to work his farm properties, but by the early 1940s was also keeping the weeds and grass in check around Norwood. The 1940 Census lists him as an automobile inspector for the safety check lane for the county. Having obviously recovered from his illness, he continued to play on the Island Queen literally through the last gasp of its second life. Homer also built his own small boats and even a houseboat which he often resided in between trips on the Island Queen.

Many steamships during World War II had been retrofitted and repainted for military transport and war related purposes. After the war they were taken to the ship yards in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for repainting and refitting back into their civilian functions. The Island Queen was moored at Pittsburgh on September 8, 1947, when a welder's torch set off fumes from a fuel tank, causing a major explosion. The crew and a number of passengers had come up to Pittsburgh where the work was being done, including Denney, and most of them had left the ship to go into town. Denney had literally just walked off the ship with his camera when the explosion occurred, and ended up taking most of the only photographs of his beloved second home on the water going up in flames, along with 19 remaining crew members trying to fight the fire from the dock. All that was left of his beloved calliope was the steel frame and four brass keys. Homer returned to Cincinnati in a pair of borrowed overalls, as all of his belongings, except his camera, had been destroyed. Having no instrument to play on, he was forced into retirement from his riverboat days. One of the end results of a career playing an instrument as loud as a jet plane was that he was mostly deaf by that time. Years of playing a mere four feet from the pipes took a permanent toll. However, he kept his day gig, as the 1950 census showed him still engaged as a meter repairman for the Norwood Water Works.

In his following years Homer played his custom Tangley Calliope in parades, and electric organs in other venues. In fact, he had not played an organ before, but secured a gig only two weeks after purchasing a portable electric model.

Among his regular organ haunts were the Cincinnati Gardens, home of many sporting events, and the Palace Gardens Skating Rink which had a very unique grand organ. He continued to supervise his farm properties and even dabbled in real estate. Still, Denney was ready at any time to lend his musical talents, often gratis, to the city of Cincinnati for parades, Shriners events, and even the Cincinnati Reds baseball team at Crosley Field starting in 1952. Homer said he enjoyed that venue the most since it was a place where he could "turn loose the volume, because the louder I play the better it sounds." He also took an interest in crank street organs (the type often associated with monkey grinders), not only restoring them but also creating rolls for them by hand. Denney did own one large instrument, a Wurlitzer 105. He wrote about his time on the river, and helped to leave a legacy about the golden days of steamships on the Ohio and the Mississippi.

|

Denney was a guest at the first St. Louis Ragtime Festival in the 1960s, according to coordinator Trebor Tichenor and performers Mike Montgomery and John Arpin, but he did not play, perhaps due to his hearing issues. It has been said that he never talked about the rags he had composed in earlier years. When his wife passed on in the late 1960s, Homer lived with his daughter June (Rotunno) in Madeira, Ohio. His last known gig was in 1971 when the Coney Island amusement park in Cincinnati was closed. In his last few months in 1975 he lived in the Ohio Masonic Home in Springfield. Homer Denney left us in September of that year, just as a new generation of ragtime fans started discovering some of the great folk rags of the ragtime era, including those of the well-known calliopist.

Thanks go to the remaining members of the Denney family, including his granddaughter Judy Carr, who willingly provided a great deal of background information on the composer. This allowed the author to finally pinpoint his evasive and clearly misspelled 1900 census entry. Also, to performer and historian Fred Hoeptner who provided some additional information on Denney through a back issue of the Rag Times. More can be found on Denney and the Island Queen at the comprehensive www.steamboats.org. A fine series of pictures of the ship and its travails is available online from the Cincinnati Libray at wiki.cincinnatilibrary.org/index.php/Island_Queen. Also, thanks to Jeremy Stevenson who uncovered the rare Sammy's Wigglin' Dance.

Compositions

Compositions