|

Abraham Holzmann (August 19, 1874 to January 16, 1939) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1899

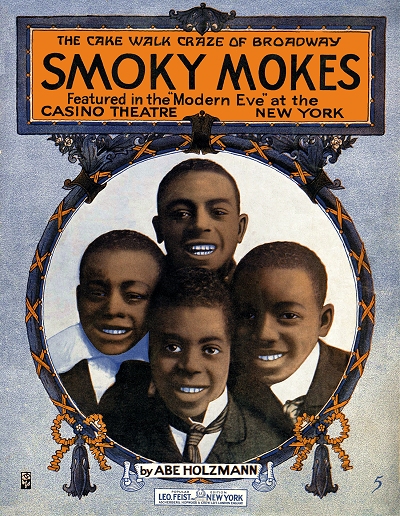

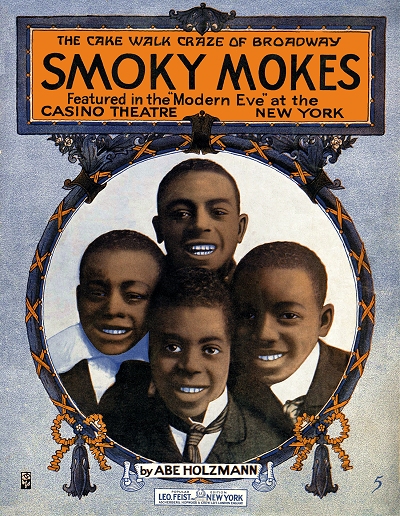

Smoky MokesBunch o' Blackberries Smoky Mokes (Song) [1] You'll Have to Transfer 1900

Hunky DoryBunch o' Blackberries (Song) Calanthe: Waltzes 1901

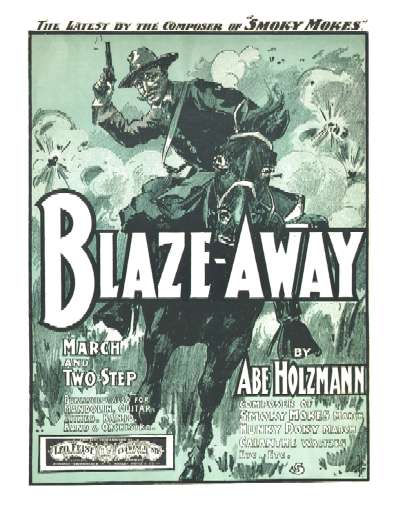

Affinity MarchBlaze-Away! Jumping-Jacks Jubilee The Hand that Rocks the Cradle Rules the World [2] 1902

Blaze AwayAlagazam Symphia: Waltzes 1903

Alagazam (Song)1904

Uncle Sammy (Inst)Uncle Sammy (Song) Spirit of Independence Nyomo: A Mexican Love Song 1905

Loveland: WaltzesYankee Grit Good Old Timers 1906

Flying ArrowMandy |

1907

Cowperthwait Centennial MarchOld Faithful 1908

Get on the Raft With Taft [3]A Great Event: The Santa Claus March 1909

Love Sparks: Waltzes1910

Blaze of Glory1911

The Winning Fight: March1912

The Spirit of Independence1913

The Whip1914

First Love (Premier Amour): Waltz1915

A-la-carte1916

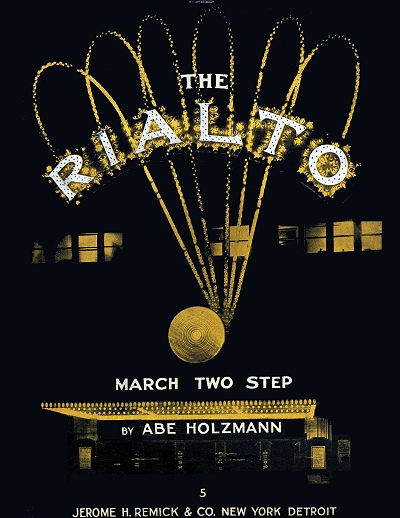

The Rialto1922

Jack Canuck1931

Blaze-Away! (Song) [4]St. Louis Times Military March

1. w/W. Murdoch Lind

2. w/Carroll Fleming 3. w/Harry D. Kerr 4. w/Jimmy Kennedy |

Abraham Holzmann was born in New York City in 1874 to Hungarian immigrant (interchangeable with German as many sources cite) Jacob Holzmann and his Louisiana born wife Isabella Finkel. According to the 1880 census the family was living in New York with Jacob working in wholesale tobacco, and Abraham's sister Charlotte "Lottie" had been added to the family (1/31/1877), later followed by sister Ester "Estelle" (7/8/1881). Jacob soon became a cigar manufacturer himself. The family is next seen in official records taking a trip to Hamburg, and possibly on to Hungary, in August of 1889.  What happened to the family in the 1890s is unclear. However, Abe's father Jacob, 20 or more years older than his bride, passed away while on business in Chicago, Illinois, on October 20, 1891. His mother soon remarried to Aschel Worms, who was of German descent. This added 2 stepsisters and 3 stepbrothers into Abe's extended family, and an additional brother was born to the couple. Two other children born to Isabella had died before 1900. During the mid-part of the 1890s, Abe received a fine music education, learning skills in notation, music theory and harmony, and piano performance. Some of this was evidently learned in Germany, but much of his education was received at the New York Conservatory of Music. And where did all this training lead him? Into the emerging genre of American popular music.

What happened to the family in the 1890s is unclear. However, Abe's father Jacob, 20 or more years older than his bride, passed away while on business in Chicago, Illinois, on October 20, 1891. His mother soon remarried to Aschel Worms, who was of German descent. This added 2 stepsisters and 3 stepbrothers into Abe's extended family, and an additional brother was born to the couple. Two other children born to Isabella had died before 1900. During the mid-part of the 1890s, Abe received a fine music education, learning skills in notation, music theory and harmony, and piano performance. Some of this was evidently learned in Germany, but much of his education was received at the New York Conservatory of Music. And where did all this training lead him? Into the emerging genre of American popular music.

What happened to the family in the 1890s is unclear. However, Abe's father Jacob, 20 or more years older than his bride, passed away while on business in Chicago, Illinois, on October 20, 1891. His mother soon remarried to Aschel Worms, who was of German descent. This added 2 stepsisters and 3 stepbrothers into Abe's extended family, and an additional brother was born to the couple. Two other children born to Isabella had died before 1900. During the mid-part of the 1890s, Abe received a fine music education, learning skills in notation, music theory and harmony, and piano performance. Some of this was evidently learned in Germany, but much of his education was received at the New York Conservatory of Music. And where did all this training lead him? Into the emerging genre of American popular music.

What happened to the family in the 1890s is unclear. However, Abe's father Jacob, 20 or more years older than his bride, passed away while on business in Chicago, Illinois, on October 20, 1891. His mother soon remarried to Aschel Worms, who was of German descent. This added 2 stepsisters and 3 stepbrothers into Abe's extended family, and an additional brother was born to the couple. Two other children born to Isabella had died before 1900. During the mid-part of the 1890s, Abe received a fine music education, learning skills in notation, music theory and harmony, and piano performance. Some of this was evidently learned in Germany, but much of his education was received at the New York Conservatory of Music. And where did all this training lead him? Into the emerging genre of American popular music.In 1898, Abe got a job as a pianist, and perhaps composer, with the fledging firm of Feist and Frankenthaler, started by Leo Feist and Joe Frankenthaler. The combination would make at least Feist and Holzmann famous for some time. With the popularity of cakewalks on the rise, Abe was allegedly asked by Leo (perhaps it was more like a mutual conversation) to compose one of them. According to an account by Feist that was published in 1920 in the Brooklyn Standard Union:

He called it 'Echoes of the South,' because echoes of anything was good. But that wasn't my practice. If it's the style to do one sort of thing, I do something else. I never imitate. So I called it by the name of 'Smoky Mokes.' I built that from a memory of an old chimney sweep of my infant days—his name had been Moke, and I tried Moke the Smoke and Moke's Smoke, and finally set on Smoky Mokes. At first real bands wouldn't put such a crazy name on their programmes. But it went over like a shot, and it was the biggest hit of the day.

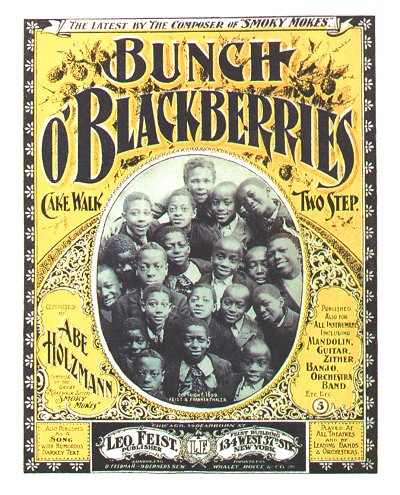

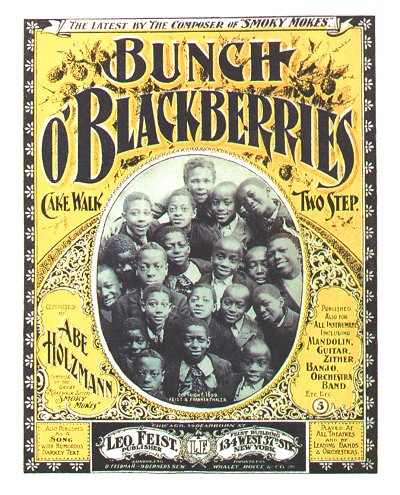

Feist and Frankenthaler released Smoky Mokes, and then Bunch O' Blackberries, into the wild. The covers, most likely chosen by Feist or his staff, showed different groups of little black boys, thus serving as visual puns for both of the titles but not necessarily intended as stereotyping. Smoky Mokes was dedicated to composer and journalist Monroe H. Rosenfeld, who may have helped Abe with connections in New York. Both pieces did well and were soon picked up by John Philip Sousa for his band thanks to some heavy promotion by Feist. Reports suggest that Sousa himself rarely conducted the rags or cakewalks his band performed, usually delegating that responsibility to his assistant Arthur Pryor. Reception was evidently mixed at first, but the pieces ended up selling quite well during the Cakewalk craze of 1900-1904, and were often recorded as well. The following is an excerpt from the New York Herald of Sunday, January 13th, 1901, which was reprinted on the back of another Feist publication in promoting Hunky Dory, a 1900 entry by Holzmann that featured the same style cover as the previous cakewalks. It is a colorful combination of fact and hyperbole. Corrections or comments are [in brackets].

GERMAN [sic] COMPOSER WHO WRITES AMERICAN CAKEWALK MUSIC

There is in this country at the present time a celebrated writer of classical music [nothing known of before 1899] whose propensity for composing darkie dances has given him an international reputation. His name is A. Holzmann and he is a German [sic] of high musical education. His knowledge of bass and counterpoint is thorough, and his standard compositions bear the stamp of harmonic lore, which makes his proclivity for the writing of the popular style of music the more remarkable. Still, he continues to compose the latter, and with such unqualified success that his name has now become associated with the leading successes in this line in the country.

When John Philip Sousa [more likely Pryor] raised his baton to the opening measures of Composer Holzmann's famous "Smoky Mokes" last season, the noted bandmaster's audience was nonplussed. Then surprise gave way to delight and vociferous applause. Persons in the audience consulting their programmes discovered a new genius in their midst. From that hour the name of Holzmann was a byword for American cakewalks, and "Smoky Mokes" re-echoed upon the pianos of a million music lovers. Then followed "A Bunch of Blackberries" and other famous oddities in Southern music by the same composer.

An interesting idea of the American love for the Antonín Dvorák theme in the plantation melody is seen in Composer Holzmann's latest creation, "Hunky Dory". As can be gleaned from the accompanying extract of this quaint composition, the music is a happy combination of the cake walk and the two-step. the melody is rhythmical and full of jingling originality and tempts one's feet to impulsive action. The HERALD presents this unique creation to its readers from Composer Holzmann's original manuscript [more likely from one of the publisher's plates]. The dance will be simultaneously produced in England, France and Germany during the coming month, and is already in vogue with the leading orchestras and bands in this country.

As for the "classical music" that Holzmann was a "celebrated writer" of, searches through a number of fairly substantial databases have turned up nothing of note before his initial 1899 entries, which were popular. As with the mistaken identity of German origin, perhaps he was simply known for playing or arranging classical music, for if he was composing such works then it appears they were not being published, even if performed. Following his initial successes, which were considerable, Holzmann worked as an arranger and staff for Feist, and did come out with a few intermezzos and waltzes that were fairly well crafted in late 19th century style. But his major output followed popular trends, including more cakewalks, marches, songs, and even some American Indian lore music, prescient in the latter half of the 1901-1910 decade. The 1900 enumeration showed Abe living in Manhattan with his parets, step-siblings, and sisters. He was listed as a music composer and Lottie as a piano teacher.

As with the mistaken identity of German origin, perhaps he was simply known for playing or arranging classical music, for if he was composing such works then it appears they were not being published, even if performed. Following his initial successes, which were considerable, Holzmann worked as an arranger and staff for Feist, and did come out with a few intermezzos and waltzes that were fairly well crafted in late 19th century style. But his major output followed popular trends, including more cakewalks, marches, songs, and even some American Indian lore music, prescient in the latter half of the 1901-1910 decade. The 1900 enumeration showed Abe living in Manhattan with his parets, step-siblings, and sisters. He was listed as a music composer and Lottie as a piano teacher.

As with the mistaken identity of German origin, perhaps he was simply known for playing or arranging classical music, for if he was composing such works then it appears they were not being published, even if performed. Following his initial successes, which were considerable, Holzmann worked as an arranger and staff for Feist, and did come out with a few intermezzos and waltzes that were fairly well crafted in late 19th century style. But his major output followed popular trends, including more cakewalks, marches, songs, and even some American Indian lore music, prescient in the latter half of the 1901-1910 decade. The 1900 enumeration showed Abe living in Manhattan with his parets, step-siblings, and sisters. He was listed as a music composer and Lottie as a piano teacher.

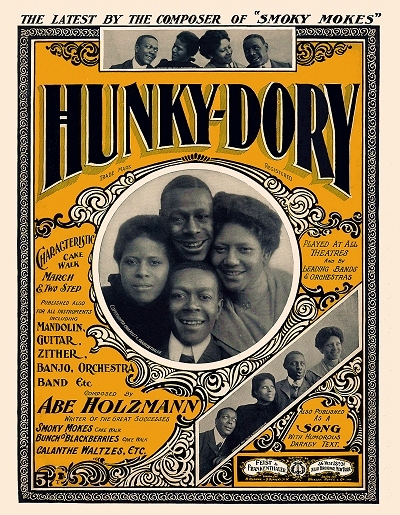

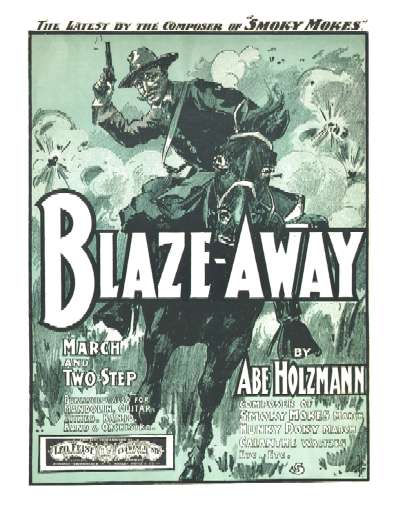

As with the mistaken identity of German origin, perhaps he was simply known for playing or arranging classical music, for if he was composing such works then it appears they were not being published, even if performed. Following his initial successes, which were considerable, Holzmann worked as an arranger and staff for Feist, and did come out with a few intermezzos and waltzes that were fairly well crafted in late 19th century style. But his major output followed popular trends, including more cakewalks, marches, songs, and even some American Indian lore music, prescient in the latter half of the 1901-1910 decade. The 1900 enumeration showed Abe living in Manhattan with his parets, step-siblings, and sisters. He was listed as a music composer and Lottie as a piano teacher.In 1901 one of Abe's best loved marches emerged. Titled Blaze Away, it appears to be a tribute to Rough Rider turned President Theodore Roosevelt, who may be the figure depicted on the cover. As with many of Holzmann's other works, this was picked up by Sousa's band, and became popular with circus bands as well. It turned out to be his last substantial hit on piano rolls and early band records as well. Uncle Sammy, a 1904 patriotic march, also proved to be somewhat popular for more than a decade. Displaying a softer side, Abe composed Loveland Waltzes in 1905, which saw a number of piano roll and phonograph renditions for many years. He contributed to the growing cache of Native-American themed pieces with Flying Arrow in 1906. One curious entry in 1907 was his Cowperthwait Centennial March, celebrating the 100th anniversary of a Manhattan carpet and furniture department store, Cowperthwait & Sons. This one was distributed by the store, rather than by publisher Feist.

In 1908 Abe came out with three fine pieces, including one campaign song for William Howard Taft's Presidential run, The Whip which was essentially a train wreck march based on a popular melodrama, and Old Faithful, which was aimed at dog lovers and their trusted pets. Early that year Holzmann made a ten-week promotional trip for Feist to most of the larger cities in the United States where they did direct business. As he told The Music Trade Review just prior to his mid-January departure, "My trip has no actual business significance, inasmuch as my intention is to visit the trade socially, if only to express Mr. Feist's appreciation for their untiring efforts in pushing his publications... Another reason for my tour is that my new march 'Old Faithful' has already shown signs of popular approval, and of course I will endeavor to interest the retailer in this number, which I think is going to be an enormous seller." Abe married Isabelle "Belle" Fishblatt on April 26, 1906. Their daughter Natalie Holzmann was born on June 2, 1909.

Abe married Isabelle "Belle" Fishblatt on April 26, 1906. Their daughter Natalie Holzmann was born on June 2, 1909.

Abe married Isabelle "Belle" Fishblatt on April 26, 1906. Their daughter Natalie Holzmann was born on June 2, 1909.

Abe married Isabelle "Belle" Fishblatt on April 26, 1906. Their daughter Natalie Holzmann was born on June 2, 1909.For the 1910 census the Holzmanns were shown as living with her parents, and he is the manager of a music publisher, which was Leo Feist. However, in February 1912 Abe left Feist, and by March he had gone to work for the dominant New York and Detroit house of Jerome H. Remick & Company. He was hired by Remick to manage the Band and Orchestra department. They were responsible for creating and distributing complete orchestrations of current Remick tunes for orchestras and bands to perform. Around the same time, he was appointed the bandmaster of the Mecca Shrine Band in New York. Holzmann's output had been consistently light, if significant, but was trimmed to only one piece annually from 1909 to 1916, albeit each piece saw a measure of success to go with its accompanying hype. In 1915 Feist capitalized on a resurgence of the cakewalk with a reissue of Smoky Mokes, bringing renewed exposure to Holzmann and fellow cakewalk composer Kerry Mills whose At a Georgia Campmeeting was also enjoying fresh sales 16 years after it release. One late march was the winner of a 1916 contest for the composition of a piece to open the new Rialto Theater in Manhattan. Holzmann's The Rialto won out over fifty other entries, and quickly found its way to a popular piano roll as well.

In 1916 Abe finally retired from composition in order to manage affairs on a larger scale at Remick. He made his mark on some retail and distribution practices within the company, and was featured in a Music Trade Review article of June 16, 1917 on this very topic, part of which is quoted here:

Abe Holzmann, Manager of the Band and Orchestra Department of Jerome H. Remick & Co., Tells Why the Sheet Music Dealer Should Be the Logical Distributor of Orchestrations

One of the problems of the sheet music trade has been that of deciding on the exact status of the retail dealer as an efficient distributor of band and orchestra music. During the past few years the dealer has had accorded more general recognition as a distributor of that class of music, although it has been maintained by some publishers that the most satisfactory method was that of direct distribution from the publisher to the band or orchestra leader.

...The Review interviewed Abe Holzmann, manager of the band and orchestra department of Jerome H. Remick & Co., who is known personally to practically every band and orchestra leader in the country, but in every case where it is possible he prefers the leader to deal directly with the dealer in his locality.

"It is with pleasure that the house of J. H. Remick & Co. sees the recognition which has been and is being given the sheet music dealer as a distributor of band and orchestra music," declared Mr. Holzmann, "and it is with considerable pride that we point to the fact that our house was one of the first to offer such recognition. We have found that the policy has proven most successful and it has paid to continue it.

"We not only cater to the dealer for the purpose of getting him to handle our publications, but we want him to feel that in handling them he is doing so at a liberal profit. We insure this profit by placing our band and orchestra publications in his hand at 15 cents each. He is expected to sell them at 25 cents and we stick to that price ourselves, to protect the dealer from being undersold. The dealer who handles orchestrations properly, and gives real attention to the department, will find that it attracts trade to his store and increases the sale of piano copies and other forms of music...

"We not only cater to the dealer for the purpose of getting him to handle our publications, but we want him to feel that in handling them he is doing so at a liberal profit. We insure this profit by placing our band and orchestra publications in his hand at 15 cents each. He is expected to sell them at 25 cents and we stick to that price ourselves, to protect the dealer from being undersold. The dealer who handles orchestrations properly, and gives real attention to the department, will find that it attracts trade to his store and increases the sale of piano copies and other forms of music..."Remick & Co. have evolved a special system for placing their band and orchestra publication on the market. In the first place, no such music is published unless it goes before what I term a 'board of censors' and this eliminates the chance of dead numbers being issued. All numbers are only selected after careful consideration and after the song or instrumental number has been demanded by orchestra leaders in various parts of the country..."

Another feature of the Remick publications and one in which Mr. Holzmann takes first prize is the care that is being given to the editing of every piece of music and for that matter to every detail of its production, plates, paper and printing being of first quality. Every proof must pass through three hands for correction as insurance against error.

"Conditions affecting bands and orchestras throughout the country were never better," declared Mr. Holzmann, "and while there are still many old timers in the active ranks, a newer element has made its appearance and is steadily gaining in strength..."

"The publishers of New York," he continues, "have seen a change come over the methods of distributing band and orchestra music. In the past, the dealer only ordered such publications as were actually in demand and for which he had calls and made no effort to carry a stock of that sort of music. The dealer, however, is constantly being recognized to a greater degree and this fact has proven beneficial to both the retailer and the publisher. It would seem that even closer co-operation between these two important trade factors is to be looked for in the near future..."

As the war effort increased in Europe in 1916 and 1917, many of Holzmann's earlier marches, such as Uncle Sammy and The Winning Fight found new popularity on roll and record. On his 1918 draft record he and Isabelle were shown as living across the Hudson in East Orange, New Jersey, near Thomas Edison's haunt of West Orange. He also appeared as a Remick manager in the 1920 enumeration. In 1923 Holzmann finally joined ASCAP nearly a decade after it was formed.

Being a civic minded individual and somewhat of a community leader as well as one in publishing, Holzmann was active in a number of groups, including the Masonic Lodge, Elks Club, and the Knights of Pythias. It appears he continued in his capacity as a manager at Remick until around 1924 when he went to work as the band and orchestra department leader at rival Shapiro, Bernstein & Company. In the firm's announcement of his acquisition, they noted that: "He has traveled at one time or another in practically every State in the Union and his first-hand knowledge of orchestra requirements in every part of the country stands him in good stead."

For the 1930 census Abe still listed himself as a publisher of music, although the firm name is not shown. His daughter Natalie, now 20, was also contributing to the household, working as a secretary in a local brokerage. The following year, lyricist Jimmy Kennedy, who had made a hit out of John W. Bratton's Teddy Bear's Picnic by adding lyrics to it, did the same for Blaze Away. While not as popular as the Bratton piece, it did see renewed interest for a short time. The timing, however, coming out during the depths of the Great Depression, did not favor great success. Holzmann left music publishing in late 1933, and spent the remainder of his life working as the advertising manager for The International Musician, the paper for the International Federation of Musicians, based in Newark, New Jersey. He died in East Orange in January 1939 at age 64, just as prosperity was coming around the corner. Holzmann lives on, however, in the traditional jazz groups and ragtime bands that continue to perform his most popular pieces in their concerts.