It is sometimes difficult to give a complete discussion of some people's lives without including another significant person that was, in many ways, intertwined with them. This is one of those cases. Whereas Harry O. Sutton had a few successes on his own, the bulk of his professional and personal life through his untimely death involved Jean Lenox, although for many years some of the details and even perceptions of their relationship was clouded in unresolved mysteries and uncertainty. In addition to the author's work to untangle this, researcher Sue Attalla helped to clarify some of the details of their relationship, and together we have been able to verify much of the story, some presented here (and on her site) for the first time.

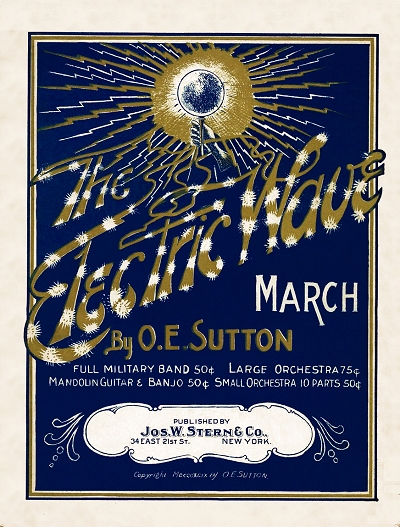

Harry Owen Sutton was born in the small town of Naples, New York, just west of the center of the state. He was one of five children born to musician and music teacher Professor Owen Eugene Sutton and his wife Alice French, the others being Myron Carl (2/6/1880), Gertrude L. (6/1883), and two more who did not survive childhood. Harry almost didn't as well. According to The [Naples] Neapolitan of July 20, 1887, just before he turned six, he fell into a water flue at a local factory, and was saved by the owner, or may have otherwise drowned. There was likely trouble brewing in the Sutton household in the mid-1890s. Owen and Alice were evidently having marital issues, and would soon be divorced, with Owen remarrying in 1893 to another Alice, namely Alice Reynick of Rochester, New York. He would make his home there around 1886, working as a musician and composer, and teaching at the Rochester Conservatory of Music (eventually merged with the D.K.G. Institute, which combined became the Eastman School of Music). He also had several works published there from the late 1880s into the early 1900s. This made Harry a third-generation music professional, since his grandparents, Myron Clark Sutton and Olive Marretta, were both musicians of note who ran a music business in Naples, as well as Sutton's Band led by Myron.

This made Harry a third-generation music professional, since his grandparents, Myron Clark Sutton and Olive Marretta, were both musicians of note who ran a music business in Naples, as well as Sutton's Band led by Myron.

This made Harry a third-generation music professional, since his grandparents, Myron Clark Sutton and Olive Marretta, were both musicians of note who ran a music business in Naples, as well as Sutton's Band led by Myron.

This made Harry a third-generation music professional, since his grandparents, Myron Clark Sutton and Olive Marretta, were both musicians of note who ran a music business in Naples, as well as Sutton's Band led by Myron.By February of 1892, as per the New York State census, 10-year-old Harry was in the process of moving to the home of his paternal aunt Mary Louise Sutton, and her farmer husband, Frank G. Pierce. In fact, the Pierces and Harry were enumerated in both Naples and their home of Richmond, Ontario County, New York, likely one or two days apart, indicating that they were practically on the way home to Richmond as they were counted in Harry's former home. Mary Louise was shown as working in the music business, which may have been the influence of her father. To that end, it appears that she was a professional keyboardist, also having been an organist at the Presbyterian church in Richmond. She also encouraged Harry's continuing music education, probably contributing to it. According to an item found by ragtime researcher Sue Attala, Harry may have given his first public performance at a Presbyterian social in April 1893 in the Pierce home, playing a duet with his aunt. This was followed in June 1895 by a performance of the Presbyterian Junior Christian Endeavor Society, singing I Long to See the Girl I Left Behind at a church event. Harry was further noted in the Neapolitan in other musical and dramatic events through at least 1897.

By mid-to-late 1897, Harry was living in Olean, New York, around 350 miles west of New York City, residing with his divorced mother (she claimed a widowed status in the 1900 census), his two surviving siblings, aunt Nellie D. French and his maternal grandmother Olive D. French. His father was shown to be living in Rochester in 1900 with his second wife and three children, Harry's half siblings, and working as a music composer. Harry hoped for that same success and started writing his own works. A 1911 notice in the Naples Record mentioned the Black Diamond Express, a march reportedly written by Harry around 1893 when he was 12. However, any evidence of this, or even verification of the year of publication was unavailable, making this only a possibility. It also claimed he was already conducting an orchestra at the Academy of Music in Rochester, which is also difficult to substantiate outside of that claim.

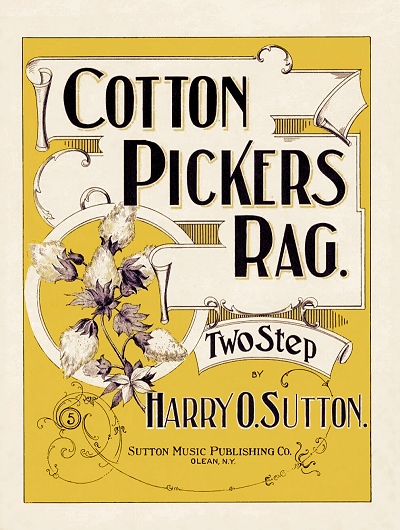

What can be verified is that Sutton's first known published piece, issued in Olean in April of 1898 when he was still 17, was Sweet Nancy Lee, composed to lyrics by Will W. Leland, who was around six years older than Harry. Sutton also copyrighted and self-published (with some assistance) at least three works from Olean in 1899, including Cotton-Picker's Rag, his first published instrumental, followed by a waltz and a cakewalk. Some of the covers indicate a printing showing a New York City address, possibly a proxy, on 14th Street, which was the main publishing street at that time prior to most of the houses moving up to 28th Street. Over the next few years Cotton-Pickers and Aunt Jemima would not only be heard on vaudeville stages, but via early piano rolls as well.

Sutton also copyrighted and self-published (with some assistance) at least three works from Olean in 1899, including Cotton-Picker's Rag, his first published instrumental, followed by a waltz and a cakewalk. Some of the covers indicate a printing showing a New York City address, possibly a proxy, on 14th Street, which was the main publishing street at that time prior to most of the houses moving up to 28th Street. Over the next few years Cotton-Pickers and Aunt Jemima would not only be heard on vaudeville stages, but via early piano rolls as well.

Sutton also copyrighted and self-published (with some assistance) at least three works from Olean in 1899, including Cotton-Picker's Rag, his first published instrumental, followed by a waltz and a cakewalk. Some of the covers indicate a printing showing a New York City address, possibly a proxy, on 14th Street, which was the main publishing street at that time prior to most of the houses moving up to 28th Street. Over the next few years Cotton-Pickers and Aunt Jemima would not only be heard on vaudeville stages, but via early piano rolls as well.

Sutton also copyrighted and self-published (with some assistance) at least three works from Olean in 1899, including Cotton-Picker's Rag, his first published instrumental, followed by a waltz and a cakewalk. Some of the covers indicate a printing showing a New York City address, possibly a proxy, on 14th Street, which was the main publishing street at that time prior to most of the houses moving up to 28th Street. Over the next few years Cotton-Pickers and Aunt Jemima would not only be heard on vaudeville stages, but via early piano rolls as well.Harry may have had a challenging relationship with his father, in part due to the geography issue and considerable distance between Olean and Rochester in a time when trains were the primary means of travel. However, they still shared music as their passion. This was confirmed in early 1900 when they gave a series of concerts in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in the spring of 1900. According to a notice in the Wilkes-Barre Times of March 29, the concerts, held at Jonas Long's Sons' store (a local department store), featured father and son playing their own compositions, including "waltzes, songs, two-steps and popular coon songs." Why they did these free concerts so far from either of their homes is unclear, since promotion of the artists or their employers was usually involved. Whether they did more appearances beyond this is also inconclusive, pending location of any more notices of this type. It is a certainty that Owen would learn of his son's growing success one way or another before he died in 1907.

For the 1900 enumeration, Harry was listed as a musician, and well on the way in that career path. He had been playing various gigs in the area while still based in Olean, and was known to be a capable sight-reader and accompanist. Harry also regularly worked with the local orchestra, probably at the piano. He issued one more work from Olean, a waltz, in 1901. Still living there in early 1903, Harry managed to wrangle a position in New York City at one of the larger publishing houses, Shapiro, Bernstein & Company. As announced in the Music Trade Review of February 7:

The latest man to join the already large staff of Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. is H. O. Sutton. He looks after the orchestrations. Mr. Sutton is a partner in the Sutton Music Publishing Co., of Olean, N. Y.

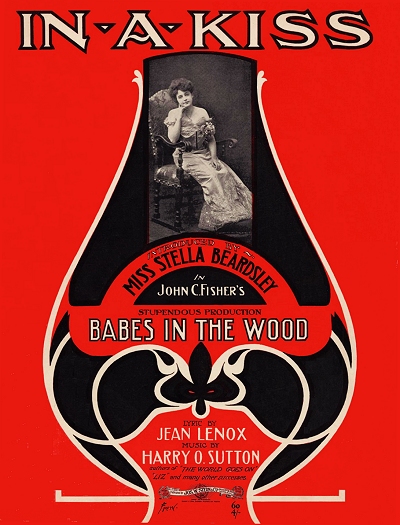

Now entering the big leagues of music, Harry also had a good outlet for distributing his works to a wider audience. There were only three in 1903, all solo efforts, but it was a start. His good fortune would come in short order when he met his real partner, but who she really was left a mystery for later researchers, and perhaps even for Harry in the beginning. Jean Veronica Pearing, born in 1878 on Long Island, New York, she had been living in Brooklyn for some time, and had been writing articles and short stories for magazines in her late teens under the name of Jean Lenox. It is unclear still as to where "Lenox" came from, but she used it for most of her life. Now in her mid-twenties (she took a few years off of that on official document), Jean ran in some of the same circles as Harry and they soon became an item. On September 23, 1903, the couple was married. Although the wedding took place in Manhattan, they may have gone back to Olean, at least for a visit, as some of their earliest collaborations were published there by Harry's small concern.

but who she really was left a mystery for later researchers, and perhaps even for Harry in the beginning. Jean Veronica Pearing, born in 1878 on Long Island, New York, she had been living in Brooklyn for some time, and had been writing articles and short stories for magazines in her late teens under the name of Jean Lenox. It is unclear still as to where "Lenox" came from, but she used it for most of her life. Now in her mid-twenties (she took a few years off of that on official document), Jean ran in some of the same circles as Harry and they soon became an item. On September 23, 1903, the couple was married. Although the wedding took place in Manhattan, they may have gone back to Olean, at least for a visit, as some of their earliest collaborations were published there by Harry's small concern.

but who she really was left a mystery for later researchers, and perhaps even for Harry in the beginning. Jean Veronica Pearing, born in 1878 on Long Island, New York, she had been living in Brooklyn for some time, and had been writing articles and short stories for magazines in her late teens under the name of Jean Lenox. It is unclear still as to where "Lenox" came from, but she used it for most of her life. Now in her mid-twenties (she took a few years off of that on official document), Jean ran in some of the same circles as Harry and they soon became an item. On September 23, 1903, the couple was married. Although the wedding took place in Manhattan, they may have gone back to Olean, at least for a visit, as some of their earliest collaborations were published there by Harry's small concern.

but who she really was left a mystery for later researchers, and perhaps even for Harry in the beginning. Jean Veronica Pearing, born in 1878 on Long Island, New York, she had been living in Brooklyn for some time, and had been writing articles and short stories for magazines in her late teens under the name of Jean Lenox. It is unclear still as to where "Lenox" came from, but she used it for most of her life. Now in her mid-twenties (she took a few years off of that on official document), Jean ran in some of the same circles as Harry and they soon became an item. On September 23, 1903, the couple was married. Although the wedding took place in Manhattan, they may have gone back to Olean, at least for a visit, as some of their earliest collaborations were published there by Harry's small concern.Until recently, it was unclear what happened after this. However, the marriage originally appeared to have perhaps been annulled. It may have been undertaken in the first place as an unnecessary response to a pregnancy scare that was found to be false, or perhaps some intervention or a realization that they were not meant to be married to each other, although further research indicated that this was not the case. It did not help that over the following years Jean was, at times, referred to as Harry's wife, or Harry as Jean's brother, so the relationship of the two was known to many, but the nature of it varied, depending on the source.

This becomes complicated further as Harry got married again on January 18, 1905, this time to one Vera G. Pearing in Holyoke, Massachusetts. The marriage record showed him claiming it to be his first marriage, another curiosity, but his profession as musician and the home for both of them to be New York City. In addition, Vera claimed her mother to be M.E. Ravenel, which raises questions about the name Jean used for the 1903 marriage application. Although the claimed birth year of 1883 does not match Jean's, the use of Vera instead of Veronica and G. instead of Jean echoes the variants in her mother's name mentioned earlier. There was also the 1905 New York State census which showed the couple residing at the Hotel Markwell in Manhattan, listed as an actor and actress. Thanks to some additional information from fellow ragtime researcher Sue Attalla, there is a concurrence that Jean and Vera were one and the same, but that Jean potentially kept the identities separate for professional reasons at a time when it was difficult enough for a woman to be taken seriously as a songwriter. It should also be considered that she put out misleading statements and stories that further deflected the possibility that she and Harry were anything more than friends – or even siblings. This shrouded identity situation would soon be further confused by another factor.

but his profession as musician and the home for both of them to be New York City. In addition, Vera claimed her mother to be M.E. Ravenel, which raises questions about the name Jean used for the 1903 marriage application. Although the claimed birth year of 1883 does not match Jean's, the use of Vera instead of Veronica and G. instead of Jean echoes the variants in her mother's name mentioned earlier. There was also the 1905 New York State census which showed the couple residing at the Hotel Markwell in Manhattan, listed as an actor and actress. Thanks to some additional information from fellow ragtime researcher Sue Attalla, there is a concurrence that Jean and Vera were one and the same, but that Jean potentially kept the identities separate for professional reasons at a time when it was difficult enough for a woman to be taken seriously as a songwriter. It should also be considered that she put out misleading statements and stories that further deflected the possibility that she and Harry were anything more than friends – or even siblings. This shrouded identity situation would soon be further confused by another factor.

but his profession as musician and the home for both of them to be New York City. In addition, Vera claimed her mother to be M.E. Ravenel, which raises questions about the name Jean used for the 1903 marriage application. Although the claimed birth year of 1883 does not match Jean's, the use of Vera instead of Veronica and G. instead of Jean echoes the variants in her mother's name mentioned earlier. There was also the 1905 New York State census which showed the couple residing at the Hotel Markwell in Manhattan, listed as an actor and actress. Thanks to some additional information from fellow ragtime researcher Sue Attalla, there is a concurrence that Jean and Vera were one and the same, but that Jean potentially kept the identities separate for professional reasons at a time when it was difficult enough for a woman to be taken seriously as a songwriter. It should also be considered that she put out misleading statements and stories that further deflected the possibility that she and Harry were anything more than friends – or even siblings. This shrouded identity situation would soon be further confused by another factor.

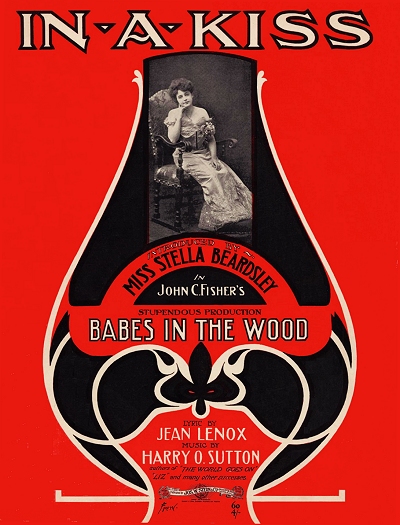

but his profession as musician and the home for both of them to be New York City. In addition, Vera claimed her mother to be M.E. Ravenel, which raises questions about the name Jean used for the 1903 marriage application. Although the claimed birth year of 1883 does not match Jean's, the use of Vera instead of Veronica and G. instead of Jean echoes the variants in her mother's name mentioned earlier. There was also the 1905 New York State census which showed the couple residing at the Hotel Markwell in Manhattan, listed as an actor and actress. Thanks to some additional information from fellow ragtime researcher Sue Attalla, there is a concurrence that Jean and Vera were one and the same, but that Jean potentially kept the identities separate for professional reasons at a time when it was difficult enough for a woman to be taken seriously as a songwriter. It should also be considered that she put out misleading statements and stories that further deflected the possibility that she and Harry were anything more than friends – or even siblings. This shrouded identity situation would soon be further confused by another factor.Jean and Harry started writing songs together in 1904. Their first tune was, appropriately enough, titled Ragtime. It was followed by Kokomo: A Japanese Love Song, based on an instrumental of the same name that he had written, and which made for a minor hit. It was not until 1905 that Jean's name was made, as her contribution to their big hit song was arguably more important than Harry's fine score. The story of the song was relayed by Jean in the March 14, 1908 edition of the Music Trade Review:

We were both ambitious, and between us we came to the conclusion that song writing might be made profitable if we could solve the mighty problem of getting a singer of note to place our efforts before the public. Our first opportunity came unexpectedly. I had been introduced to Miss Eva Tanguay, as a "writer," and with an air of polite boredom Miss Tanguay inquired what sort of writer I was. With my heart thumping at my audacity I murmured "song writer," and whether it was a desire to be polite or whether Miss Tanguay had a well-defined sympathy for the song-writing craft, I have never since been able to discover, Still in quite a sociable way she asked me to write her something. A weak feeling came over me. In my vivid imagination I was already counting prospective royalties.

We were both ambitious, and between us we came to the conclusion that song writing might be made profitable if we could solve the mighty problem of getting a singer of note to place our efforts before the public. Our first opportunity came unexpectedly. I had been introduced to Miss Eva Tanguay, as a "writer," and with an air of polite boredom Miss Tanguay inquired what sort of writer I was. With my heart thumping at my audacity I murmured "song writer," and whether it was a desire to be polite or whether Miss Tanguay had a well-defined sympathy for the song-writing craft, I have never since been able to discover, Still in quite a sociable way she asked me to write her something. A weak feeling came over me. In my vivid imagination I was already counting prospective royalties.As soon as I could rally sufficiently I managed to murmur "delighted, I am sure," or words to that effect. I then asked what sort of song she required. Miss Tanguay, who seemed to regret her hasty commission, remarked "I don't care so long as it's good." That night with the words "I don't care" ringing in my ears, I sat up late—very late—and evolved my first lyric, which has since been presented in a printed form to the public under the title "I Don't Care."

Wise ones have told me that to write that lyric I must have known Miss Tanguay all her life. I consider it quite the prettiest compliment ever paid me.

Even though the song I Don't Care was not quite Jean's first, and certainly not Harry's, it became arguably their most famous work, with several verses that described Tanguay's character and attitude quite well. That would pretty much be that no matter what people thought of the outrageous singer's stage antics, she did not care and would continue to be who she was. Many have followed in Tanguay's footsteps since, even with songs to go along with their mantra, including such 21st century notables as Madonna, Lady Gaga and Meghan Trainor. But as with Tanguay, they needed material to express themselves in that way. Four additional tunes that the couple had written were interpolated into Tanguay's musical play, The Sambo Girl, staged in late 1905. They included a retooling of Ragtime recast as the ethnic tune A Ragtime Jap.

Many have followed in Tanguay's footsteps since, even with songs to go along with their mantra, including such 21st century notables as Madonna, Lady Gaga and Meghan Trainor. But as with Tanguay, they needed material to express themselves in that way. Four additional tunes that the couple had written were interpolated into Tanguay's musical play, The Sambo Girl, staged in late 1905. They included a retooling of Ragtime recast as the ethnic tune A Ragtime Jap.

Many have followed in Tanguay's footsteps since, even with songs to go along with their mantra, including such 21st century notables as Madonna, Lady Gaga and Meghan Trainor. But as with Tanguay, they needed material to express themselves in that way. Four additional tunes that the couple had written were interpolated into Tanguay's musical play, The Sambo Girl, staged in late 1905. They included a retooling of Ragtime recast as the ethnic tune A Ragtime Jap.

Many have followed in Tanguay's footsteps since, even with songs to go along with their mantra, including such 21st century notables as Madonna, Lady Gaga and Meghan Trainor. But as with Tanguay, they needed material to express themselves in that way. Four additional tunes that the couple had written were interpolated into Tanguay's musical play, The Sambo Girl, staged in late 1905. They included a retooling of Ragtime recast as the ethnic tune A Ragtime Jap.In the interim, Harry had been a partner in the Theatrical Music Supply Company on 28th Street, partnering with F.W. Helmick and a few others. According to The Music Trade Review of August 12, 1905, the company went into receivership in the summer of 1905 due to issues with Helmick's management, so he perhaps wanted a more stable position in the publishing world following that incident. As to the process that Harry and Jean sometimes used for songs, one not uncommon in the songwriting world even more than a century later, the following story, which may stretch the truth just a little, was relayed in the Music Trade Review of October 14, 1905:

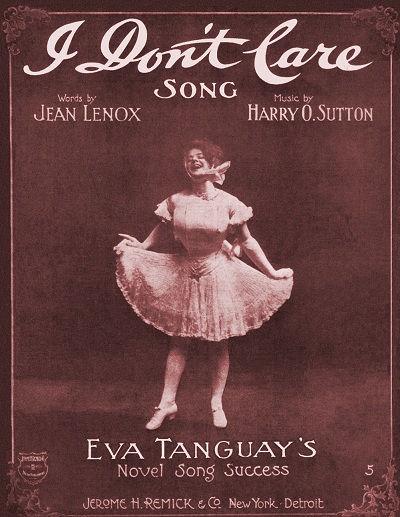

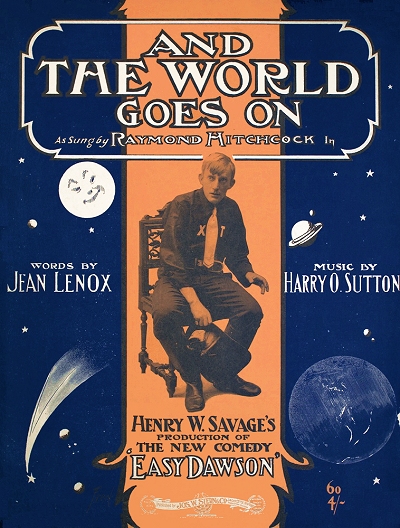

The true story of how that remarkably catchy song in "Easy Dawson," "And the World Goes On," was written, few persons believe, but they are persons who have not met Jean Lenox. The song was written for Mr. Henry W. Savage in exactly 12 minutes, and the music ditto. A phenomenal feat to all appearances, but the fact remains that 12 minutes from the time the first telephone bell rang a messenger, sent by Miss Lenox, was on his way to Mr. Harry O. Sutton, the composer, with the scribbled lines, and in 12 minutes more he, too, had done his stunt. The combined efforts of the clever pair, therefore, covered less than one-half hour to turn out the popular song.

Among other things, this article either demonstrated or at least gave the illusion that Jean and Harry were not married and lived at separate addresses. At least one of those situations was not true. Sutton and Lenox, who allegedly had penned a deal with Joseph Stern in 1904 to be their exclusive publisher, continued to write together and turn out hits. Their ability to do so, in addition to a shift in allegiance to their publisher, was profiled in the Music Trade Review of March 3, 1906:

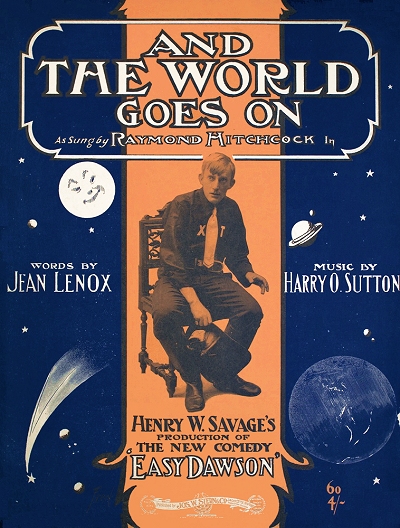

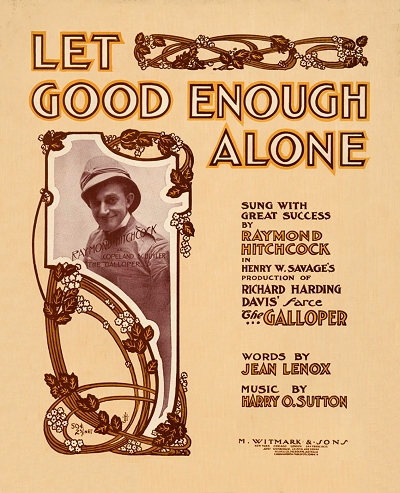

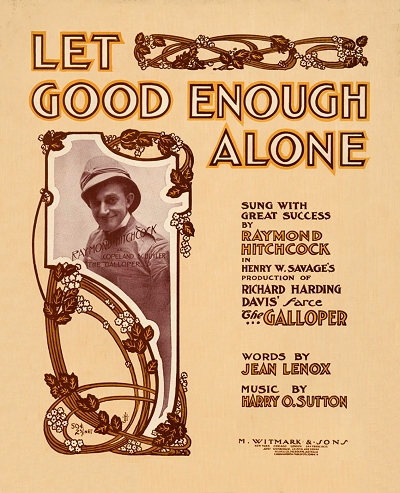

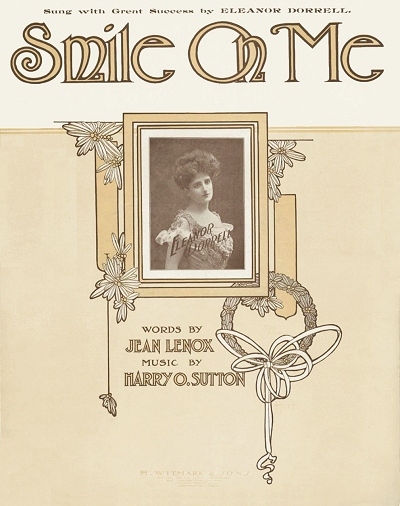

Although the youngest team of song writers known to the realm of popular music, at least so far as the length of their term of co-partnership is concerned, Lenox and Sutton have already established for themselves a prominent and permanent reputation. They have just signed an agreement with M. Witmark & Sons, making that firm the exclusive publishers of their compositions. With the signing of the contract they handed the Witmarks a hit in the song, "Let Good Enough Alone," now being sung in "The Galloper" by Raymond Hitchcock, who is taking his audiences by storm with its aid. This fine comedian previously sang "The World Goes On," by the same writers, in "Easy Dawson." The team of Lenox and Sutton is composed of Jean Lenox and Harry O Sutton, an exceptionally talented and brilliant pair, who have, within a very short time, written some remarkable successes, among them "Smile on Me," sung by Eddie Leonard, Virginia Earle and a host of other bright lights of the musical stage—another recent Witmark hit.

Other noteworthy songs from their pen, which are soon to see daylight, are "Persuasion" and "Love Dreams." These will be featured by such popular professionals as Eva Tanguay, Anna Laughlin, Adele Ritchie, Truly Shattuck, Pauline Hall, Blanche Ring, Irene Bentley, George Primrose and many others who have sung their compositions heretofore…

By the end of 1906 Lenox and Sutton would also attempt a full operetta on a story that had already been done in European opera, The Rose of Castile. While it was briefly staged in vaudeville, at least one reviewer deemed it as, "a bit ambitious and rather above the complete appreciation of ordinary vaudeville audiences." So in the spring of 1908, the behind-the-scenes show business couple decided to step in front of the proscenium. Jean turned out to be a moderately effective stage performer with Harry at the piano, and as such found a way to create a spectacle almost worthy of Tanguay, as described in this March 25, 1908 article in the Music Trade Review:

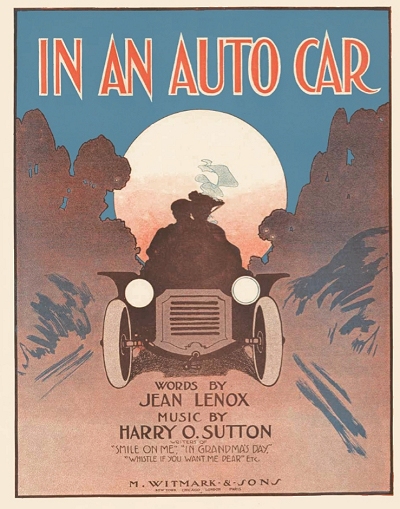

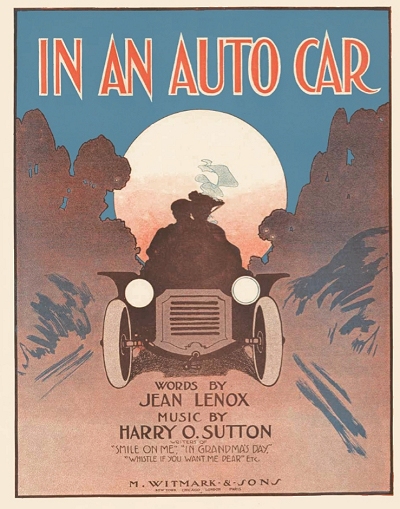

On Monday night Easton, Pa., was treated to a novelty in vaudeville which made the oldest inhabitant sit up in his seat and piously exclaim "B'gosh." When the neatly painted front drop of the theater, on which the advertisements of the local tradespeople are neatly inscribed, arose on a perfectly dark stage displaying what looked for all the world like a flying automobile with flaring headlights, in which was seated a dainty girl with fluffy golden hair blowing in all directions, the town constable arose and in all his majesty demanded that the occupants of the car consider themselves under arrest for exceeding the speed limit.

At this moment, however, the lights went up to disclose that the dangerous automobile was nothing more alarming than a grand piano made, by the way, by Paul G. Mehlin & Sons, at which Miss Jean Lenox was seated and from which she rendered a clever little song entitled "In an Auto Car." Subsequently dressed in all sorts of delightful costumes which our "Man on the Street" being a mere man and totally unacquainted with the intricacies of feminine garb dare not attempt to describe, Miss Lenox sang five whole songs—count 'em—entitled, "All the Boys Look Good to Me," "Acushla," "I'd Rather Be Like Pa," and "Whistle if You Love Me, Dear." It may be said that the writer has been whistling ever since he heard this number…

As a performer, a critic in Variety noted that: "Miss Lenox has a sweet appearance, but is without voice, and delivers her songs in a hesitating, uncertain manner, all but amateurish. As a 'straight' singer Jean Lenox will not upset vaudeville." As for her partner, "Harry O. Sutton assisted on the piano, and acquitted himself admirably." Despite the pan, the pair were signed up for thirty-five weeks on the Keith & Proctor vaudeville circuit in June. Not long after this, a syndicated article appeared noting that Jean had been offered a position as an editor for a well-known women's magazine, complete with a "flattering salary," based on her prior experience as a writer. Evidently now enamored with the stage, she turned down the position in favor of her music.

Although the reason is not clear, Jean had to undergo emergency surgery in July of 1908. By the fall she was recovered enough to resume her songwriting and stage appearances plugging her material composed with Harry as well as her stage routines. One tune of 1908 that received a great deal of universal praise was In Grandma's Day, which was suggested by her own grandmother's discouragement at the type of songs she had been writing to that point. Her response was a fine ballad that was rife with nostalgia, and attempted to honor grandmas everywhere. After trio of works issued in 1909 following, Lenox and Sutton had no further joint publications. This was probably due to the onset of tuberculosis in Harry, which eventually took his life. According to a March 17, 1909 article in the Naples News, Harry had suffered a bout of typhoid fever in the summer of 1908, and claimed he perhaps had overworked himself in subsequent months, now convalescing in Allentown, near the Appalachian Mountains, looking for an "open air cure" for the early stages of tuberculosis. Yet another article in the Naples News in early 1911 suggests that his sickness went back as far as 1907. Another notice at the time of Harry's death indicated that while in Allentown he was working for the Harned-Early Department Store in their music department. Whether or not Jean was there is unclear, but it seems likely that she remained in New York City for at least some of this period.

One tune of 1908 that received a great deal of universal praise was In Grandma's Day, which was suggested by her own grandmother's discouragement at the type of songs she had been writing to that point. Her response was a fine ballad that was rife with nostalgia, and attempted to honor grandmas everywhere. After trio of works issued in 1909 following, Lenox and Sutton had no further joint publications. This was probably due to the onset of tuberculosis in Harry, which eventually took his life. According to a March 17, 1909 article in the Naples News, Harry had suffered a bout of typhoid fever in the summer of 1908, and claimed he perhaps had overworked himself in subsequent months, now convalescing in Allentown, near the Appalachian Mountains, looking for an "open air cure" for the early stages of tuberculosis. Yet another article in the Naples News in early 1911 suggests that his sickness went back as far as 1907. Another notice at the time of Harry's death indicated that while in Allentown he was working for the Harned-Early Department Store in their music department. Whether or not Jean was there is unclear, but it seems likely that she remained in New York City for at least some of this period.

One tune of 1908 that received a great deal of universal praise was In Grandma's Day, which was suggested by her own grandmother's discouragement at the type of songs she had been writing to that point. Her response was a fine ballad that was rife with nostalgia, and attempted to honor grandmas everywhere. After trio of works issued in 1909 following, Lenox and Sutton had no further joint publications. This was probably due to the onset of tuberculosis in Harry, which eventually took his life. According to a March 17, 1909 article in the Naples News, Harry had suffered a bout of typhoid fever in the summer of 1908, and claimed he perhaps had overworked himself in subsequent months, now convalescing in Allentown, near the Appalachian Mountains, looking for an "open air cure" for the early stages of tuberculosis. Yet another article in the Naples News in early 1911 suggests that his sickness went back as far as 1907. Another notice at the time of Harry's death indicated that while in Allentown he was working for the Harned-Early Department Store in their music department. Whether or not Jean was there is unclear, but it seems likely that she remained in New York City for at least some of this period.

One tune of 1908 that received a great deal of universal praise was In Grandma's Day, which was suggested by her own grandmother's discouragement at the type of songs she had been writing to that point. Her response was a fine ballad that was rife with nostalgia, and attempted to honor grandmas everywhere. After trio of works issued in 1909 following, Lenox and Sutton had no further joint publications. This was probably due to the onset of tuberculosis in Harry, which eventually took his life. According to a March 17, 1909 article in the Naples News, Harry had suffered a bout of typhoid fever in the summer of 1908, and claimed he perhaps had overworked himself in subsequent months, now convalescing in Allentown, near the Appalachian Mountains, looking for an "open air cure" for the early stages of tuberculosis. Yet another article in the Naples News in early 1911 suggests that his sickness went back as far as 1907. Another notice at the time of Harry's death indicated that while in Allentown he was working for the Harned-Early Department Store in their music department. Whether or not Jean was there is unclear, but it seems likely that she remained in New York City for at least some of this period.The 1910 census for Jean showed her living alone in New York City, listed as a literary writer, although locating any periodicals that she may have been writing for was met with no success. Harry was also living in Manhattan, but showed that he had been widowed, which was sometimes used to negate the connotation of being divorced. (An obituary even suggested his second wife was living in St. Louis, but no evidence of that was found.) Just the same, no clear evidence of any divorce has been located to date. Harry was caring for his son Lloyd Carl (1907 - some sources show him as Loyd, but his signature verified it to be Lloyd) in addition to his own widowed mother, although given that her name was Mary E. it was most likely Jean's mother helping to raise her grandson, and she had been misidentified by the enumerator. He was listed as the manager of a music publishing house, which would have been M. Witmark & Sons at that time. The question would then be posed as to whether Lloyd was also Jean's son, and if so, why the separation. If not, then there would be a clear reason for that separation. It is probable that Jean still wanted to be viewed as single and independent, but not as an unwed mother. On Lloyd's marriage record years down the road, his mother was listed as Vera, but on his death record as Jean, making his parentage clearer.

Harry was caring for his son Lloyd Carl (1907 - some sources show him as Loyd, but his signature verified it to be Lloyd) in addition to his own widowed mother, although given that her name was Mary E. it was most likely Jean's mother helping to raise her grandson, and she had been misidentified by the enumerator. He was listed as the manager of a music publishing house, which would have been M. Witmark & Sons at that time. The question would then be posed as to whether Lloyd was also Jean's son, and if so, why the separation. If not, then there would be a clear reason for that separation. It is probable that Jean still wanted to be viewed as single and independent, but not as an unwed mother. On Lloyd's marriage record years down the road, his mother was listed as Vera, but on his death record as Jean, making his parentage clearer.

Harry was caring for his son Lloyd Carl (1907 - some sources show him as Loyd, but his signature verified it to be Lloyd) in addition to his own widowed mother, although given that her name was Mary E. it was most likely Jean's mother helping to raise her grandson, and she had been misidentified by the enumerator. He was listed as the manager of a music publishing house, which would have been M. Witmark & Sons at that time. The question would then be posed as to whether Lloyd was also Jean's son, and if so, why the separation. If not, then there would be a clear reason for that separation. It is probable that Jean still wanted to be viewed as single and independent, but not as an unwed mother. On Lloyd's marriage record years down the road, his mother was listed as Vera, but on his death record as Jean, making his parentage clearer.

Harry was caring for his son Lloyd Carl (1907 - some sources show him as Loyd, but his signature verified it to be Lloyd) in addition to his own widowed mother, although given that her name was Mary E. it was most likely Jean's mother helping to raise her grandson, and she had been misidentified by the enumerator. He was listed as the manager of a music publishing house, which would have been M. Witmark & Sons at that time. The question would then be posed as to whether Lloyd was also Jean's son, and if so, why the separation. If not, then there would be a clear reason for that separation. It is probable that Jean still wanted to be viewed as single and independent, but not as an unwed mother. On Lloyd's marriage record years down the road, his mother was listed as Vera, but on his death record as Jean, making his parentage clearer.By 1910 the Sutton/Lenox songs had all been written, although Jean wrote a couple more with other composers. On February 23, 1911, Harry Owen Sutton died of tuberculosis at age 29 in Brooklyn. A couple of the obituaries mentioned Jean as the wife he left behind, even though Harry had been reportedly widowed. Some even persisted in referring to Jean as his sister. He was laid to rest in Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York. It was then decided that Lloyd would come to live with Jean, who despite claims to the contrary in some public records, was clearly closest thing to family that Harry had left, mother or not. The 1915 New York census taken in Manhattan showed Jean as a literary writer, Lloyd as her nephew, and a German immigrant maid, likely engaged to care for the boy

After sending Lloyd to Washington, DC around 1917 to reside with her brother Thomas and mother Mary, Jean went out west to Hollywood to try her hand at film writing and acting. In the late spring of 1919, she returned to Manhattan. Then it appears that she either tired of New York, or more likely became ill and retreated to Washington, DC, where Lloyd and Mary still lived. Jean Lenox died there on August 24, 1919. It is unclear what took her life, but pulmonary tuberculosis is suspected. The 1920 enumeration taken in Washington, however, did help to answer one question. It showed Thomas Pearing as the head of household, working as a board of health clerk, hosting his mother Mary as well as Lloyd, who was listed as his nephew, making it evident that without Jean's intervention to claim otherwise, he was clearly her son. Lloyd went on to work as a jeweler, sadly dying divorced and alone from pneumonia complicated by the ravages of alcoholism, at age 45 in 1952 in Salem, Oregon. Just the same, both Jean and Harry left some unanswered questions behind, particularly concerning their marital status and relationship as a whole.

There remains at least one other unanswered question. Several works by Harry and Jean were afforded copyright renewal in the 1930s, and were ostensibly done so showing "©Jean Lenox as author of w[ork]." Thomas had died before this time, also of tuberculosis, so it was clearly not him. Could this have been Lloyd or some other relation? Admittedly the vetting process for who submitted recopyrighting of work was rather insufficient at that time, so we may never know who submitted these, or who was collecting any supposed royalties from sales, as ASCAP does not have a record of this since she never joined and Harry died before it was formed in 1914. Hopefully some of these mysteries will be solved in the future.

There were a number of variegated sources used to compile this article, including public and government records, and several newspaper articles and periodicals. Special thanks to fellow researcher Sue Attalla who helped to untangle and de-mystify what the author had already suspected about the Lenox-Sutton relationship, which led to more confirming factors on various parts of their lives. You can read her detailed take on this at https://www.sueattalla.com/

Compositions

Compositions