Harold Pinder, who made one interesting contribution to the ragtime repertoire, did not leave much information about himself behind. It appears, however, that he had his own reasons for doing so, which will become clear as the sad story unfolds. Harold was the only child of leather belt maker Rudolph E. Pinder and his wife Helen E. McEvoy, all born in Massachusetts. The 1900 enumeration showed the family living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and by 1910 they were residing in nearby Hudson, where the census for that year showed Rudolph working from home in the leather business. His son, however, was more interested in the music business.

where the census for that year showed Rudolph working from home in the leather business. His son, however, was more interested in the music business.

where the census for that year showed Rudolph working from home in the leather business. His son, however, was more interested in the music business.

where the census for that year showed Rudolph working from home in the leather business. His son, however, was more interested in the music business.The first publication found by Harold was published when he was 17. It was a song written with one Gladys E. Stone, about whom nothing was found in Boston newspapers or directories. However, by 1918 it was clear that Harold considered himself to be a musician. He had moved to Albany, New York, where he filled out his draft registration. As it was weeks before the end of the war it is unlikely he was ever called up. The following year Harold was listed in the directory for Troy, New York. It was from here that his next three works appeared in print, all under the name Rednip, which was his last name in reverse. The reason he chose this particular pseudonym is unclear, but he retained it for the bulk of his published compositions. A surviving family member noted that he had attended the Julliard School of music, and perhaps graduated, but this was difficult to confirm.

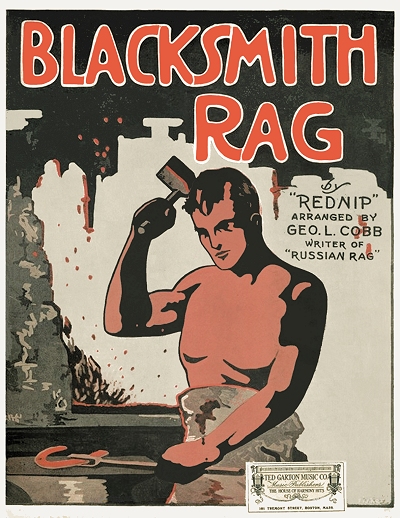

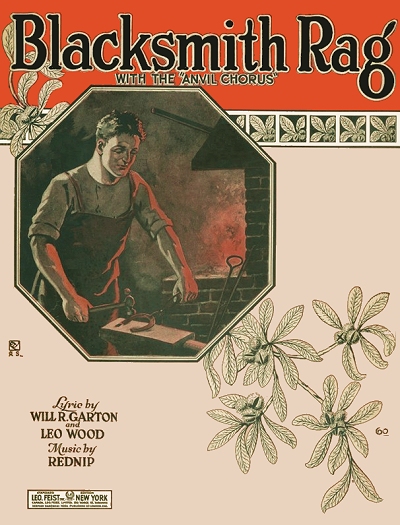

For the 1920 census taken in January, Harold was back in Massachusetts, living again with his parents in Somerville. Rudolph was now working as a belt maker in a factory, and Harold was listed as a music teacher. There was a notice in the Fitchburg [Massachusetts] Daily Sentinel on May 10, 1920, about a concert in which Harold was performing with the Handel Trio. His most notable work was also released during the year. It was Blacksmith Rag, a humorous ragtime take on the famous Anvil Chorus by Giuseppe Verdi, and included apologies to the original composer on the cover. The piece was arranged by George L. Cobb, who was working for the Walter Jacobs Company in Boston at that time. It has been suggested that Pinder sent the work into Cobb as part of the usual flow of compositions received for the Jacobs music magazine, which Cobb edited, and often critiqued new works. However, that would imply that it was published by Jacobs, when in fact, it was issued by Will R. Garton, who also provided lyrics for a song version of the rag. How Cobb became involved is unclear, but it may have been that he was contracted, or was the friend of a friend or the like. He would be the logical choice as his recently issued Russian Rag had been doing very well. The song version was picked up by publisher Leo Feist, and used in a stage presentation titled Babes in the Wood In 1921 Pinder was engaged, as Rednip, for three more melodies, and wrote one additional song of his own, as well as arranging a couple of tunes for other composers.

In the early part of the 1920s, Pinder reportedly played on and off with the band of Paul Whiteman on both piano and ukulele, possibly on a couple of recording dates as well, but was not a permanent member of the organization, nor their primary pianist. Although he later claimed in Daily Tar Heel [Chapel Hill, North Carolina] article to have worked with the group for as long as fifteen years, by the mid-1920s Pinder was no longer traveling with Whiteman Orchestra. The 1926 Boston city directory showed Harold as a pianist. However, it appears he likely left Boston in late 1924, as he also showed up in a city directory for Westbrook, Maine, in 1925 and 1926, where he was working as a store clerk and residing with his father. A circuitous trail which was suggested by a family member and linked backwards from the death of another Pinder led to the discovery that Harold had been married in 1922 or 1923 to Isabel Marguerite Whall (8/6/1902), also of Massachusetts. They had three sons, including Lawrence Damon in 1923, and twins Lee Newman and Robert Emerson on November 16, 1925, all born in Cambridge. Whatever transpired between Harold and Isabel was likely enough that he felt the need to get out of town, far out of town, and with his complicit father.

It is possible that Harold violated the law to the point where he was being pursued, either by Massachusetts officials or agents set on him by his wife, or just shunned a life of domestication with children. In any case, he left while she was still pregnant with the twins, first making his way South, then to the Midwest. During this time, in what appears to have been an effort to disappear and start a new life, much easier in a time before Social Security and other record keeping, Harold affected the professional pseudonym Paul Weber Weston. It appears that Isabel was possibly able to secure a divorce before 1930 [the family has never been certain about this], but little else. The 1930 census showed Harold as Paul residing in Omaha, Nebraska, divorced and working as a cake maker in a local bakery. In fact, it appears that Paul steered clear of the music business for the at least the next few years, except for maybe some non-professional appearances. His ploy may have worked, at least for a while, since Isabel, now living in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania with Lawrence and running a beauty parlor, showed as widowed. The other two boys were living with nearby relatives.

On January 31, 1934, Paul, who was still on the move, was married to Ruby C. Cox in Carter County, Tennessee. They soon settled in Boone, North Carolina, where Paul ran a photography business and store. It was during this period of time that he, according to a surviving family member, "invented several pieces of development machinery in a mass production type of development of film," something similar to what would later be used in drugstores and one hour photomats.

Easing back a little from his self-imposed musical exile, Paul secured a Hammond D-100 organ for his home, and became adept at jazz. Before long, he added a third independent three-octave keyboard on top of the two-manual organ with an early electronic generator similar to a synthesizer, likely used for chimes or special effects sounds. He finally went on extended gigs as a jazz organist, touring parts of North America along with his instrument. However, he should not be confused with the better-known orchestra leader Paul Weston [b.1912], who was also touring the country at this time with his own somewhat famous group.

|

The 1940 enumeration showed the Westons living in Boone, with Paul claiming a California birth, although that may have been an enumerator error. His former wife and three sons were living in San Francisco, California, at the time of that census, having relocated there in the late 1930s. Shortly after this, when World War II was underway, Paul secured a contract with the Sheraton Hotel chain, playing at some of their key locations in the North during the summer months, and the Southern U.S. during the winter, taking his travel trailer and organ with him. During his tours he tended to use Paul Weber as his billed name, rather than Weston, perhaps to avoid any confusion with the bandleader. After the war was over, Weston went back into photography and spent more time in Boone, relegated at that time to playing on the local radio station, as well as special events in town. A picture of him at WSB in Atlanta suggests he still traveled for performances from time to time. Unfortunately, Paul lost a leg to diabetes, but was able to compensate for this loss by concocting a device that let him control the organ volume pedal with what was left of that leg.

The jig was finally up for Paul/Harold at some point in the early 1940s. A CBS network radio show titled The Missing Heirs, which was designed to track people allegedly due inheritances by telling their story and hoping somebody would recognize them, put Pinder in the spotlight. Apparently, his Yankee accent, which stood out in drawl-ridden North Carolina, gave him away, plus other aspects of his life. A woman from nearby Cove Creek, North Carolina, called the program with an identification, and an attorney soon came knocking. Harold had little choice but to admit to his deception in order to claim what was possibly his father's inheritance. This exposed him to both his old and new families, but details of how this ultimately worked out are not being made public out of respect for surviving family members. Isabel and his sons did get a decent share of this inheritance. It may explain how he was able to so readily afford his traveling organ setup. No further compositions were found under any of his collective names, so any income from written music would have been nil by this time. Interestingly enough, he kept using the Weston alias, including for the 1950 census which showed both Paul and Ruby as photo shop proprietors in Todd, North Carolina, about 12 miles from Boone.

There were a number of mentions of Paul as an organist in the Daily Tar Heel from the early-to-mid 1950s. When he eventually died at age 62 in July of 1962 as Paul Weston, his mother's correct name was put on the death certificate, but his father was curiously listed as Rudolph Weston. Paul/Harold had succumbed to a "cerebral vascular accident brought on by diabetes and heart disease." When his son Lawrence passed on in Reno, Nevada, in 1994 (as Lawrence Damon Pindar - a slight variation in spelling), the information on his death certificate pointed to Harold Pinder as his father, which is how the rest of the information came to light, thanks to a family member who set this search in motion in 2013. Not all musician stories that we post here have a happy ending, but to Harold's credit (or George L. Cobb's), Blacksmith Rag is still performed today at various ragtime events in the United States.

Thanks go to Terri Pinder Wyatt who suggested this search based on a clue that Harold might have been her grandfather, which he ultimately was, and that his name had changed, which as it turns out it had. Also to surviving members [names withheld as a courtesy] of both Paul and Ruby's families, who were kind enough to share Pinder's pictures and additional information, both as an interesting story and a cautionary tale of the ragtime/jazz musician's life!

Compositions

Compositions