Irving Berlin (Israel Isidore Balim/Baline) (May 11, 1888 to September 22, 1989) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1907

Marie from Sunny Italy [w/Nick Nicholson]1908

The Best of Friends Must PartQueenie, My Own [w/Maurice Abrahams] 1909

DorandoI Just Come Back To Say Good-Bye Just Like The Rose Oh, What I Know About You Yiddle, on Your Fiddle, Play Some Ragtime That Mesmerizing Mendelssohn Tune Before I Go and Marry I Will Have a Talk With You I Just Came Back to Say Good-Bye I Didn't Go Home At All [5] Someone's Waiting For Me {We'll Wait Wait Wait} [5] Sadie Salome Go Home! [5] Wild Cherries Rag (Song) [4] Christmas-Time Seems Years and Years Away [4] She Was A Dear Little Girl [4] If I Thought You Wouldn't Tell [4] Some Little Something About You [4] I Wish That You Was My Gal, Molly [4] No One Could Do It Like My Father [4] Oh! Where is My Wife Tonight? [4,6] Next to Your Mother, Who Do You Love? [4] Stop That Rag (Keep On Playing, Honey) [4] Do Your Duty Doctor (Oh! Oh! Oh! Doctor) [4] Sweet Marie, Make-a Rag-a-time Dance Wid Me [4] My Wife's Gone to the Country! [4,6] Someone Just Like You, Dear [4] Good-Bye Girlie (and Remember Me) [4] 1910

Sweet Italian LoveYiddisha Eyes Run Home and Tell Your Mother Wishing Stop! Stop! Stop! Come Over, and Love Me Some More Try it on Your Piano That Kazzatsky Dance Dat Draggy Rag Angelo Innocent Bessie Brown It Can't Be Did [unpublished] Alexander and His Clarionet [4] Colored Romeo [4] Call Me Up Some Rainy Afternoon [4] Telling Lies [w/Henrietta Blanke Belcher] Thank You, Kind Sir! Said She [4] Kiss Me, My Honey, Kiss Me [4] How Can You Love Such a Man? [4] Dreams, Just Dreams [4] Herman, Let's Dance That Beautiful Waltz [4] Oh, How That German Could Love [4] Sweet Italian Love [4] Bring Back My Lena to Me [4] If the Managers Only Thought the Same as Mother [4] I'm A Happy Married Man [4] I'm Going on a Long Vacation [4] Oh, That Beautiful Rag [4] Piano Man [4] Is there Anything Else I Can Do For You? [4] Wishing [4] Dear Mayme, I Love You! [4] When I Hear You Play That Piano, Bill! [4] I Love You More Each Day [4] That Opera Rag [4] The Dance of the Grizzly Bear [w/George Botsford] 1911

When You're In Town In My Home TownOne O'Clock in the Morning I Get Lonesome How Do You Do It Mabel On Twenty Dollars A Week My Melody Dream: A Song Poem The Whistling Rag He Promised Me When it Rains, Sweetheart, When it Rains Business is Business Rosey Cohen Alexander's Ragtime Band I Beg Your Pardon Dear Old Broadway Dat's-A My Gal Don't Take Your Beau to the Seashore Yiddisha Nightingale Molly-O Oh-Molly Bring Me a Ring in the Spring That Monkey Tune Bring Back My Lovin' Man Meet Me Tonight Woodman, Woodman, Spare That Tree! Everybody's Doin' It Now Cuddle Up When You Kiss An Italian Girl When I'm Alone I'm Lonesome You've Got Me Hypnotized The Ragtime Violin You've Built a Fire Down in My Heart That Mysterious Rag [4] Spanish Love [4,7] Sombrero Land [4,8] After the Honeymoon [4] Down to the "Folies Bergere" [4] Don't Put Out The Light [5] Ephraham Played Upon the Piano [7] Dog Gone That Chilly Man [7] Yankee Love [8] There's a Girl in Havana[8] Virginia Lou [w/Earl Taylor] The Dying Rag [w/Bernard Adler] 1912

The Yiddisha ProfessorThe Ragtime Mocking Bird Goody, Goody, Goody, Goody, Good A True Born Soldier Man I'm Going Back To Dixie When I Lost You That's How I Love You Follow Me Around Spring and Fall: A Tone Poem That Society Bear Don't Leave Your Wife Alone If All the Girls I Knew Were Like You Antonio You'd Better Come Home The Rag-time Jockey Man Down in My Heart Wait Until Your Daddy Comes Home The Ragtime Soldier Man My Sweet Italian Man When I'm Thinking Of You When That Midnight Choo, Choo, Leaves For Alabam' Take a Little Tip From Father Call Again Pick, Pick, Pick, Pick on the Mandolin Antonio A Little Bit of Everything Do It Again Keep Away From the Fellow Who Owns an Automobile I'm Afraid Pretty Maid I'm Afraid Becky's Got a Job in a Musical Show I've Got To Have Some Lovin' Now The Elevator Man (Going Up! Going Up! Going Up!) Come Back to Me, My Melody [4] Take a Little Tip From Father [4] I Want To Be In Dixie [4] When Johnson's Quartet Harmonize Lead Me To That Beautiful Band [8] The Million Dollar Ball [8] He Played it on His Fid, Fid, Fiddle Dee-Dee [8] Hiram's Band [8,9] Alexander's Bag-Pipe Band [8,9] 1913

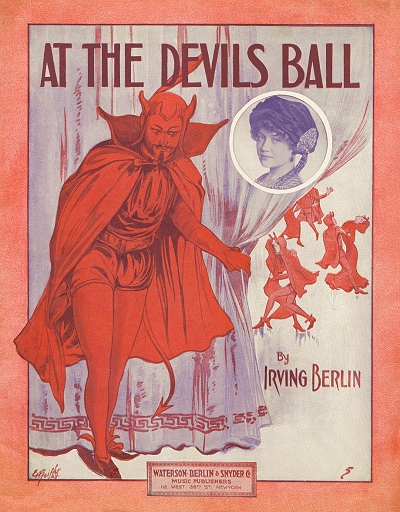

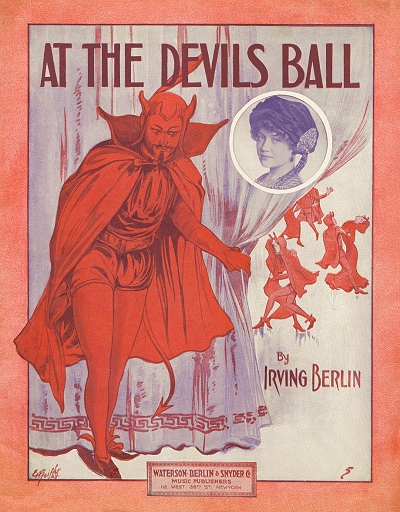

San Francisco BoundSomebody's Coming To My House You Picked a Bad Day Out to Say Good-Bye Happy Little Country Girl Snooky Ookums Keep On Walking Down in Chattanooga Take Me Back Daddy Come Home If You Don't Want Me, Why Do You Hang Around? At the Devil's Ball Tra-la, La, La! He's So Good To Me The Monkey Doodle Doo The Old Maid's Ball The Apple Tree and the Bumble Bee In My Harem Abie Sings an Irish Song Welcome Home That International Rag Anna Liza's Wedding Day We Have Much to be Thankful For Kiss Your Sailor Boy Goodbye You've Got Your Mother's Big Blue Eyes They've Got Me Doin' It Now: Medley I Was Aviating Around [1,7] There's a Girl in Arizona [10,5] The Ki-I-Youdleing Dog [w/Jean Schwartz] Jake, Jake, (The Yiddish Ball Player) [11] Pullman Porters Parade [1] 1914

This is the LifeThat's My Idea of Paradise I Want to Go Back to Michigan (Down on the Farm) They're On Their Way To Mexico Come to the Land of the Argentine When It's Night Time Down in Dixieland If You Don't Want My Peaches (You Better Stop Shaking the Tree) Furnishing a Home For Two If I Had You God Gave You To Me He's a Rag Picker The Haunted House Always Treat Her Like a Baby If That's Your Idea of a Wonderful Time - Take Me Home I Love to Quarrel With You Along Came Ruth It Isn't What He Said (But the Way He Said It) Follow the Crowd Stay Down Here Where You Belong Morning Exercises Fox Trot He's a Devil in His Own Home Town [10] Watch Your Step: Musical Office Hours What is Love? The Dancing Teacher The Minstrel Parade Let's Go Around the Town They (Always) Follow Me Around Show Us How To Do The Fox Trot When I Discovered You [8] The Syncopated Walk Metropolitan Nights I Love to Have the Boys Around Me Settle Down in a One-Horse Town Chatter Chatter Ragtime Opera Medley (Old Operas in a New Way) Move Over (Won't You Play a) Simple Melody Look At Them Doing It Lock Me in Your Harem and Throw the Key Away Homeward Bound (added 1915) I Hate You (added 1915) Lead Me to Love (added 1915) I've Got a Go Back to Texas (printed 1916) 1915

When You're Down in Louisville (Call On Me)When I Leave the World Behind My Bird of Paradise The Voice of Belgium Cohen Owes Me Ninety Seven Dollars Homeward Bound Sailor Song I'm Going Back to the Farm I Love To Stay At Home Let's Go Around The Town While the Band Played An American Rag Araby Si's Been Drinking Cider Stop! Look! Listen!: Musical Blow Your Horn Give Us a Chance I Love to Dance And Father Wanted Me to Learn a Trade The Girl on the Magazine I Love a Piano That Hula Hula A Pair of Ordinary Coons Take Off a Little Bit Teach Me How To Love The Law Must Be Obeyed Ragtime Melodrama When I Get Back to the U.S.A. Stop! Look! Listen! I'll Be Coming Home with a Skate On Everything in America is Ragtime 1916

When the Black Sheep Returns to the FoldI've Got a Sweet Tooth Bothering Me (Pull It Out, Pull It Out, Pull It Out) The Friars Parade He's Getting Too Darn Big For A Small Town I'm Down in Honolulu (Looking Them Over) Hurry Back to My Bamboo Shack In Florida Among the Palms I'm Not Prepared The Chicken Walk When I'm Out With You Until I Fell in Love With You 1917

Smile and Show Your DimpleHow Can I Forget (When There's So Much to Remember) There Are Two Eyes in Dixie It Takes An Irishman To Make Love For Your Country and My Country Mr. Jazz Himself Wasn't It Yesterday? Poor Little Rich Girl's Dog I'll Take You Back To Italy The Road That Leads To Love Whose Little Heart Are You Breaking Now? Someone Else May Be There While I'm Gone My Sweetie From Here to Shanghai Dance and Grow Thin: Musical Way Down South (There's Something Nice About the South) [11] Birdie [11] Cinderella Lost Her Slipper [11] Mary Brown [11] The Kirchner Girls [11] Don't Look at Me [11] Letter Boxes (Just Placed in New York) [11] Dance and Grow Thin [12] Let's All Be Americans Now [5,12] 1918

The Cohan Revue of 1918: Musical [13]Polly Pretty Polly (Polly With A Past) Show Me the Way When Ziegfeld's Follies Hit the Town Our Acrobatic Melodramatic Home Spanish The Eyes of Youth (See the Truth) All Dressed Up in a Tailor-Made The Potash and Perlmutter Ball A Man is Only a Man King of Broadway The Wedding of Words and Music The Gathering of the Slaves The Slave Dance A Bad Chinaman from Shanghai Down Where the Jack O'Lanterns Glow The Old Maid Blues Who Do You Love? Their Hearts are Over Here When the Curtain Falls Over the Sea Boys I'm Gonna Pin a Medal on the Girl I Left Behind The Devil Has Bought Up All The Coal The Blue Devils of France [2] I Have Just One Heart For Just One Boy [3] You're So Beautiful [3] Come Along to Toy Town [3] I Wouldn't Give That For The Man Who Couldn't Dance [3] The Circus is Coming to Town [3] It's the Little Bit of Irish [3] Good-Bye France (You'll Never Be Forgotten) [3] Yip Yip Yaphank: Army Musical [3] Hello, Hello, Hello Bevo What a Difference a Uniform Will Make Mandy The Ragtime Razor Brigade Ding Dong Come Along, Come Along, Come Along Love Interest Jazz Land (Dream on Little) Soldier Boy Send a Lot of Jazz Bands Over There Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning Kitchen Police (Poor Little Me) (I Can Always Find a Little Sunshine) in the Y.M.C.A. We're on Our Way To France 1919

The Canary. Fox Trot [3] [W.B. Kernell]Was There Ever a Pal Like You? Everything is Rosie Now for Rosie [10] Sweeter Than Sugar (Is My Sweetie) I Lost My Heart in Dixie Land When My Baby Smiles Revolutionary Rag I Wonder Nobody Knows (and Nobody Seems to Care) The New Moon I Left My Door Open and My Daddy Walked Out Eyes of Youth The Hand That Rocked My Cradle Rules My Heart I Never Knew [w/Elsie Janis] Ziegfeld Follies of 1919: Musical You'd Be Surprised I've Got My Captain Working For Me Now I'd Rather See A Minstrel Show The Follies Minstrels Mandy (from Yip Yip Yaphank) Harem Life I'm the Guy Who Guards the Harem (And My Heart's in My Work) A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody Prohibition You Cannot Make Your Shimmy Shake On Tea [w/Rennold Wolf] The Near Future A Syncopated Cocktail My Tambourine Girl Look Out For The Bolsheviki Man We Made the Doughnuts Over There 1920

Beautiful Faces (Need Beautiful Clothes)But! (She's Just a Little Bit Crazy About Her Husband - That's All) Lindy I'll See You in C-U-B-A After You Get What You Want You Don't Want It Home Again Blues [w/Harry Akst] Ziegfeld Follies of 1920: Musical Come Along I'm a Vamp from East Broadway [w/Harry Ruby & Bert Kalmar] The Girl of My Dreams Leg of Nations Come Along: Ziegfeld Sextette Poor Floradora Girl Chinese Fantasy: Chinese Firecrackers Tell Me Little Gypsy Bells The Syncopated Vamp 1921

There's a Corner Up in HeavenDrowsy Head [w/Vaughn De Leath] I Like It All By Myself The Passion Flower At the Court Around the Corner Music Box Revue of 1921: Musical What's in the Queer-Looking Bundle? Where Am I? We Work While You Sleep We'll Take the Pilot to Ziegfeld Dancing the Seasons Away Behind the Fan In a Cozy Kitchenette Apartment My Ben Ali Haggin Girl My Little Book of Poetry A Play Without a Bedroom Say It With Music Everybody Step I Am a Dumbell The School House Blues They Call It Dancing The Legend of the Pearls An Interview with Irving Berlin 1922

Some Sunny DayHomesick Music Box Revue of 1922: Musical Lady of the Evening Pack Up Your Sins and Go to the Devil |

1922 (Cont)

Crinoline DaysPorcelain Maid Will She Come from the East? Mont Martre The Little Red Lacquer Cage Bring on the Pepper Diamond Horseshoe Three Cheers for the Red, White and Blue I'm Looking For a Daddy Long Legs Take a Little Wife 1923

Tell All the Folks in Kentucky (I'mComin' Home) Too Many Sweethearts Tell Me with a Melody When You Walked Out Someone Else Walked Right In Music Box Revue of 1923: Musical An Orange Grove in California Love to Do the Strut Little Butterfly Climbing Up The Scale Learn to Do the Strut The Waltz of Long Ago One Girl Tell Me a Bedtime Story Maid of Mesh 1924

The Happy New Year BluesAll Alone Lazy What'll I Do Music Box Revue of 1925: Musical Tell Her in the Springtime Listening In the Shade of a Sheltering Tree Where is My Little Old New York Alice in Wonderland Don't Send Me Back to Petrograd Unlucky in Love The Call of the South Rockabye Baby Who Tokio Blues 1925

Venetian IslesRemember Don't Wait Too Long Blue Skies Always The Cocoanuts: Musical The Guests The Bellhops Why Do You Want to Know Why? (added 1927) Family Reputation Ting-a-Ling, the Bells 'll Ring (revised 1926) Lucky Boy Why Am I a Hit with the Ladies? A Little Bungalow Florida By the Sea The Monkey Doodle Doo Five O'Clock Tea They're Blaming the Charleston We Should Care Minstrel Days Tango Melody Gentlemen Prefer Blondes When My Dreams Come True The Tale of a Shirt 1926

We'll Never KnowThat's a Good Girl Just a Little Longer How Many Times? Everyone in the World is Doing the Charleston At Peace With The World Because I Love You I'm On My Way Home 1927

The Song is Ended but the Melody Lingers OnWhat Does it Matter? Russian Lullaby Together, We Two Ziegfeld Follies of 1927: Musical We Want to be Glorified Ribbons and Bows Shaking the Blues Away Ooh, Maybe It's You Rainbow of Girls It All Belongs To Me It's Up to the Band Jimmy Learn to Sing a Love Song Tickling the Ivories What Makes Me Love You? The Jungle-Jingle You Gotta Have "IT" [w/Eddie Cantor] Now We are Glorified Why Must We Always Be Dreaming/ Learn to Sing a Love Song My New York 1928

Roses of YesterdayCoquette Sunshine How About Me? Marie Where is the Song of Songs For Me To Be Forgotten (Good Times With Hoover) Better Times With Al Yascha Michaeloffsky's Melody I Can't Do Without You 1929

Mammy: MovieTo My Mammy Here We Are Looking At You (Across the Breakfast Table) Let Me Sing and I'm Happy In the Morning Hallelujah: Movie Swanee Shuffle Waiting at the End of the Road Puttin' On the Ritz: Movie Puttin' on the Ritz With You 1930

Just a Little WhileThe Little Things in Life Reaching For The Moon 1931

Me!Beggin For Love I Want You for Myself 1932

I'm Playing With FireI'll Miss You in the Evening How Deep is the Ocean (How High is the Sky?) Say It Isn't So Face the Music: Musical Lunching at the Automat Let's Have Another Cup O' Coffee (And Let's Have Another Piece of Pie) Torch Song You Must be Born with It On a Roof in Manhattan (Castles in Spain) My Beautiful Rhinestone Girl Soft Lights and Sweet Music I Say It's Spinach Drinking Song Dear Old Crinoline Days I Don't Want to be Marries Manhattan Madness 1933

I Can't RememberMaybe I Love You Too Much I Never Had a Chance As Thousands Cheer: Musical How's Chances? Heat Wave Majestic Sails at Midnight Lonely Heart The Funnies To Be or Not To Be Easter Parade (Her Easter Bonnet) Supper Time Our Wedding day (I've Got) Harlem on My Mind Through a Key Hole Not For All the Rice in China 1934

Moon Over NapoliSo Help Me Butterfingers 1935

Top Hat: MovieTop Hat, White Tie and Tails No Strings (I'm Fancy Free) Cheek to Cheek The Piccolino Isn't This a Lovely Day? 1936

Follow the Fleet: MovieI'd Rather Lead a Band Get Thee Behind Me Satan We Saw the Sea But Where Are You? Let's Face the Music and Dance I'm Putting All My Eggs In One Basket Let Yourself Go 1937

On the Avenue: MovieHe Ain't Got Rhythm On the Avenue The Girl on the Police Gazette Slumming on Park Avenue On the Steps of Grant's Tomb I've Got My Love To Keep Me Warm Swing Sister This Year's Kisses You're Laughing at Me 1938

God Bless America (1918/1938)Alexander's Ragtime Band: Movie Now It Can Be Told My Walking Stick Marching Along with Time Carefree: Movie Since They Turned Loch Lomond Into Swing Carefree Change Partners The Night is Filled With Music I Used To Be Color Blind The Yam 1939

Second Fiddle: MovieWhen Winter Comes I Poured My Heart Into a Song An Old-Fashined Tune Always is New I'm Sorry For Myself Back to Back The Song of the Metronome 1940

If You BelieveA Man Chases A Girl (Until She Catches Him) Louisiana Purchase: Musical The Letter Apologia Sex Marches On Louisiana Purchase It's a Lovely Day Tomorrow Outside of That I Love You You're Lonely and I'm Lonely Dance With Me (Tonight at the Mardi Gras) Latins Know How What Chance Have I With Love? The Lord Done Fixed Up My Soul Fools Fall in Love Old Man's Darling - Young Man's Slave? You Can't Brush Me Off I'd Love to be Shot from a Cannon with You Wild About You It'll Come To You 1941

When This Crazy World is Sane AgainWhen That Man is Dead and Gone A Little Old Church in England Arms For The Love of America Any Bonds Today? Angels of Mercy 1942

I Threw A Kiss In The OceanThe President's Birthday Ball Me and My Melinda This is the Army: Musical This is the Army, Mister Jones I'm Getting Tired So I Can Sleep My Sergeant and I are Buddies I Left My Heart at the Stage Door Canteen The Army's Made a Man Out of Me Mandy (from Yip Yip Yaphank) That Russian Winter What the Well Dressed Man in Harlem Will Wear American Eagles With My Head in the Clouds Aryans Under the Sun Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning (1918) How About a Cheer for the Navy This Time My British Buddy (added 1943) Ve Don't Like It (added 1943) Holiday Inn: Movie I'll Capture Her Heart Singing You're Easy to Dance With White Christmas (1942/1948) Happy Holidays Holiday Inn Let's Start the New Year Right Abraham Be Careful, It's My Heart Song of Freedom Plenty to be Thankful For 1943

Take Me With You Soldier Boy1944

What are We Gonna Do with All the Jeeps?There are No Wings on a Foxhole All of My Life 1945

I'll Dance Rings Around YouHeaven Watch the Philippines Just a Blue Serge Suit Oh, To Be Home Again Everybody Knew But Me Blue Skies: Movie Getting Nowhere (Running Around in Circles) You Keep Coming Back Like a Song A Serenade to an Old-Fashioned Girl A Couple of Song and Dance Men 1946

Annie Get Your Gun: MusicalColonel Buffalo Bill I'm a Bad Bad Man Doin' What Comes Natur'lly The Girl That I Marry You Can't Get a Man with a Gun There's No Business Like Show Business They Say it's Wonderful Moonshine Lullaby Ballyhoo My Defenses are Down Wild Horse Ceremonial Dance I'm an Indian Too Adoption Dance Take it In Your Stride (cut) I Got Lost in His Arms Who Do You Love I Hope I Got the Sun in the Morning Anything You Can Do (I Can Do Better) I'll Share it All With You Let's Go West Again 1947

A Couple of SwellsThe Freedom Train Help Me to Help My Neighbor Kate (Have I Come Too Early, Too Late) Love and the Weather Easter Parade: Movie Steppin' Out With My Baby It Only Happens When I Dance With You Better Luck Next Time Drum Crazy A Fella With an Umbrella 1948

What Can You Do With a General?1949

I'm Beginning To Miss YouThe Honorable Profession of the Fourth Estate Miss Liberty: Musical Extra! Extra! I'd Like My Picture Took The Most Expensive Statue in the World Little Fish in a Big Pond Let's Take an Old-Fashioned Walk (originally The Race Horse and The Flea) Homework Paris Wakes Up and Smiles Only for Americans Just One Way To Say I Love You Miss Liberty The Train You Can Have Him The Policemen's Ball Follow the Leader Jig Me an' My Bundle Falling Out of Love Can Be Fun Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor Mister Monotony (cut) The Pulitzer Prize (cut) 1950

FreeCall Me Madam: Musical Mrs. Sally Adams The Hostess with The Mostes' on the Ball Washington Square Dance Lichtenburg Can You Use Any Money Today? Marrying for Love (Dance to the Music of) The Ocarina It's a Lovely Day Today The Best Thing For You (Would be Me) Something to Dance About Once Upon A Time Today They Like Ike You're Just in Love (I Wonder Why?) 1952

For The Very First TimeI Like Ike 1953

Sittin' in the SunSayonara White Christmas: Movie (We'll Follow) The Old Man Sisters The Best Things Happen While You're Dancing Snow Count Your Blessings Instead of Sheep Choreography Mandy (from Yip Yip Yaphank) Love, You Didn't Do Right by Me Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning (1918) Gee, I Wish I Was Back in the Army 1954

A Sailor's Not a Sailor ('Til a Sailor's BeenTattooed) My House Was On Fire I'm Not Afraid 1956

IKE for Four More Years1957

I Keep Running Away From YouYou Can't Lose the Blues with Colors 1962

Mr. President: MusicalLet's Go Back to the Waltz In Our Hide-Away The First Lady Meat and Potatoes I've Got To Be Around The Secret Service It Gets Lonely in the White House Is He The Only Man In The World? They Love Me Pigtails and Freckles Don't Be Afraid of Romance Laugh it Up Empty Pockets Filled With Love Glad to be Home You Need a Hobby The Washington Twist The Only Dance I Know I'm Gonna Get Him Once Every Four Years Song for a Belly Dancer This is a Great Country 1966

An Old-Fashioned Wedding(added to Annie Get Your Gun)

1. as Ren. G. May

2. as Private Irving Berlin 3. as Sergeant Irving Berlin 4. w/Ted Snyder 5. w/Edgar Leslie 6. w/George Whiting 7. w/Vincent Bryan 8. w/E. Ray Goetz 9. w/A. Baldwin Sloane 10. w/Grant Clarke 11. w/Blanche Merrill 12. w/George W. Meyer 13. w/George M. Cohan |

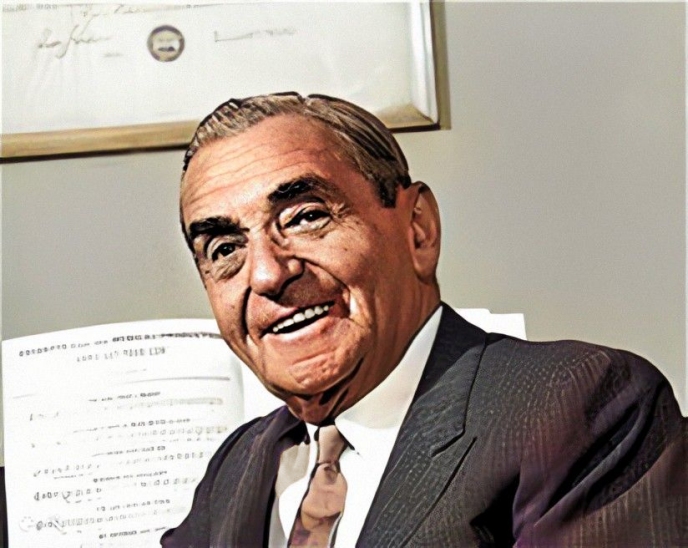

Irving Berlin, perhaps more than any other composer of the first half of the 20th Century and beyond, represents America and American Music at its finest. Given his background it becomes even more extraordinary when one understands his contributions to this adopted country of his. Berlin also managed to stay right on the cusp of popular forms to which he was contributing, not mastering them, but certainly writing into them well. It is likely that he wrote AND published more songs than any other popular song writer in history, wrote hundreds of unpublished or unpublishable tunes as well, and likely created more pieces than any other 20th century writer as both composer and lyricist. He was also quirky, but in spite of not being a movie star in stature, he was a true American favorite among the public and among the stars as well. From truly humble beginnings Berlin managed to build a musical empire and a legacy that is hard to match and remains with us in the 21st century.

Early Years

This great American was either born in Mogilev (modern day Belarus) or Tyumen, Siberia (Tehmen according to his 1942 draft record, but at variance with other records), Russia in 1888 as Israel Isidore Beilin (some sources show Balim, to Jewish parents Moses Balim and Lena Leah Yarchin (some sources show Lipkin. The 1900 enumeration shows his birth year at 1887, which would be biologically impossible given Augusta’s birthdate, therefore, 1888 is widely accepted as accurate. Israel’s father was a cantor who sometimes worked as a shochet (the person who kills animals in a kosher manner for sale and consumption) as well to support his wife and six children, including Sarah (5/1878), Benjamin (9/1881), Rebecka (5/1883) and Augusta (4/1886), two to four others having died before or in their teens. In the face of the increasing pogroms and oppression of Jews in Russia, Baline moved his family to the United States when Israel, the youngest sibling, was just five. Perhaps the first hint of the coming name change, the family is shown on the arrival list of the Rhynland on September 14, 1893, as the Beilin family, and were shown on Ellis Island records as Baline, but it is not clear whether they actually adopted the Berlin last name when they immigrated. Baline was used for the 1900 census.

Moses found work in New York certifying Kosher meat before it went to market, while his wife kept house. When Israel was around eight his father died, leaving the boy and his older brothers and sisters (one already working as a domestic) in the position of helping their mother survive in the New York ghetto. So, he and his siblings went to work as news butchers, delivery boys, and whatever odd jobs they could find, usually at the sacrifice of sufficient schooling. He picked up some singing skills as well, although the boy never had formal training in piano, voice, or even harmony and theory. He was simply a natural.

In 1902 Izzy, as he was often referred to, left home to make try to find his own way in the world. The fourteen-year-old sang in bars, or on the streets, and continued to do whatever odd jobs he could find. The hardships he encountered would stick with him throughout his life, as even though he eventually had more money that he could imagine, he was still very cautious with it. This reality may have also formed his work ethic, feeling the need to always be productive. A side job for the boy was as a song plugger or demonstrator (as a vocalist) for Harry Von Tilzer, but this was not steady work. Still, it placed him in Tony Pastor's famed Vaudeville house, and got him some notice among musicians.

By 1906, at 18, Izzy had a job as a singing waiter at Callahan's, and then Pelham's Cafe in Chinatown (some sources also cite a place called Nigger Mike's). Since a rival pub had their own song published in 1907 (it was increasingly easy to get a song into print in Manhattan by this time), the owner asked Izzy if he help to write one for Pelham's. Baline fitted lyrics to a melody by the cafe's pianist, Nick Nicholson, and in short order, Marie from Sunny Italy became the first of his songs in print. This was quite a feat as he was still having some difficulty with English, as Russian had been spoken in his home, and Yiddish was the common language on the streets, but he showed a propensity for clever rhyming. Izzy made a whopping 37 cents in royalties, but he gained something more - his famous name. The cover artist and printer misread the name and put it down as "I. Berlin," but since it sounded much more Americanized, he adopted Irving Berlin as his legal name. (Note that this is the most common story, although the Ellis Island arrival list cannot be discounted as a contributing possibility).

The published effort managed to gain Berlin some small fame, and he next found himself singing at Jimmy Kelly's establishment, a bit closer to Tin Pan Alley than he had previously been. Encouraged by the minor sucess of Marie, and in spite of what was still an English handicap, Berlin set out to contribute lyrics to more tunes. In some cases, he would create a set of lyrics and be in search of an existing melody or a potential writer for that melody. In the year following Marie this translated into a total of two more pieces. However, 1909 would prove to be the year of his emergence as a great lyricist. Remember that Babe Ruth was initially known for his pitching prowess, so that the immigrant Berlin was utilized as a pitcher of lyrics makes for a better story, once his other true talent was revealed. Berlin had been experimenting with his own melodies, which had to be hummed to a pianist who would translate them. Through watching, he soon learned enough tricks to be able to pound out his own melodies, albeit usually transcribed by a copyist or arranger.

The incident that spurred him on to be a music writer involved another early song, Dornado. Irving had his own definitive idea about how the melody for the piece should sound, but the collaborator who transcribed it came out with something quite different. So Berlin struck out to find someone who could literally translate the melody, and Dornado was born. It got him enough notice that Ted Snyder, who had recently come from Chicago and opened both Seminary Music and Ted Snyder Publishing in Manhattan, hired Berlin as a staff lyricist in early 1909. According to Berlin's obituary, he had taken a lyric to Snyder for consideration in late 1908. The newly minted publisher asked to hear the melody. Even though Irving had not considered adding his own tune to the lyric, he improvised one on the spot, hummed to Snyder's pianist/arranger, and performed it right away. Snyder was impressed enough to bring Berlin into the fold in short order. His hiring was announced in the New York Clipper on March 20, 1909:

A NEW VERSATILE SONG WRITER.

Irving Berlin, a Gifted Young Composer, Signs with the Ted Snyder Music Co.

Irving Berlin, a Gifted Young Composer, Signs with the Ted Snyder Music Co.

A lad, scarcely out of his teens, possessing remarkable talent as a popular song writer, has just signed a five year contract with the Ted Snyder Music Company. His name is Irving Berlin, and although a little over twenty years of age, the young scribe has developed an ability of more than ordinary quality. He writes all manner of songs, with a facility that is astonishing because of the fact that he has never been endowed with any musical training.

Henry Waterson, of the Ted Snyder Company, immediately recognized in young Berlin talent out of the ordinary. Encouraging him in the pursuit of his vocation, Messrs. Waterson and Snyder induced Berlin to perfect several manuscripts which they immediately proceeded to put into press. Three of these are particularly novel and valuable. They are entitled, respectively: "Sadie Salome Go Home." a comic dialect; "Dorandor!" an Italian humorous ditty, and "No One

Could Do It Like My Father," another witty efusion.

Further oddities from this writer's pen are shortly to follow and the Ted Snyder firm will push them with the same profitable vigor as has been evidenced in their famous "My Dream of the U.8.A." and "Beautiful Eyes* numbers.

Berlin and Snyder quickly turned out She Was a Dear Little Girl, which was quickly interpolated into a show on Broadway, giving them some momentum. Snyder then tried Berlin with another newcomer, Edgar Leslie, and their song Sadie Salome, Go Home eventually helped Fannie Brice land her long-time job with the Ziegfeld Follies.

While Berlin lyrics were fitted to the music of a few other Snyder composers, it soon became evident that he and Snyder were a good match, and they started turning out a number of appreciably good tunes on a regular basis. Two rags that were turned into songs with Berlin's lyrics, George Botsford's Dance of the Grizzly Bear, and Snyder's own Wild Cherries, translated into good sales for the company. Snyder also let Irving work with transcribers to turn out his own songs, including two early lasting efforts, Yiddle, on Your Fiddle, Play Some Ragtime and That Mesmerizing Mendelssohn Tune, both from 1909. In 1910, the output from Berlin as well as his collaborations with Snyder exploded in quantity, although other than Grizzly Bear there were no enormous successes. He appears in the 1910 census as Irving Berlin, head of household, living with his mother and his sister Augusta, his occupation that of Music Writer. The following year, 1911, would prove to be the turning point in Berlin's writing career, and his earliest major success was also touched with a bit of controversy.

Gaining Success

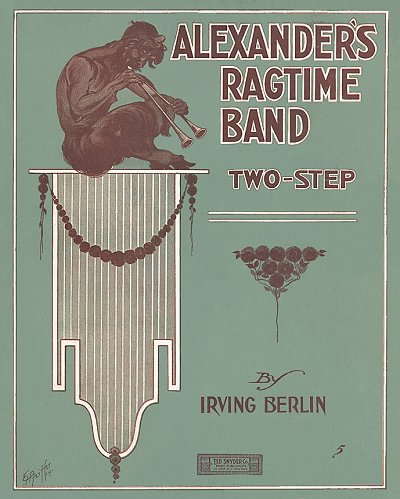

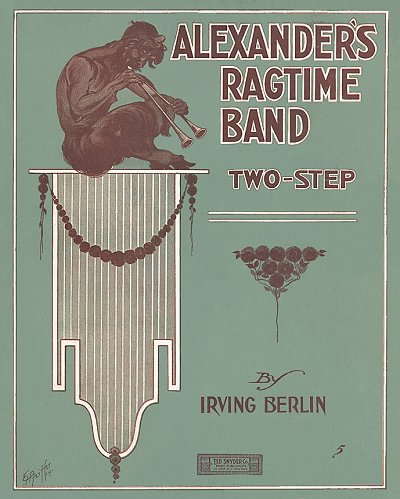

Having become more competent as a pianist, albeit in a limited fashion, but more valuable also as one who could recognize good work when it came across his desk, Berlin was also utilized to review the works of other composers for publication, and became Snyder's right hand man. One of these composers was Scott Joplin, who in 1911 was shopping his opera Treemonisha around Tin Pan Alley in hopes of getting it in print, and raising money to stage it. There is a good chance that the score came across Berlin's desk. Later in that year with the help of Snyder arranger Alfred Doyle he re-purposed an earlier unsuccessful song, Alexander and His Clarinet, with a new verse, a tune we all now know as Alexander's Ragtime Band. This new verse was highly similar to the original melody of Joplin's A Real Slow Drag which closed the opera. In fact, it was reported by Joplin's surviving wife, Lottie Stokes Joplin, that he likely altered the melody afterwards so it did not match the verse to Alexander's Ragtime Band. A newspaper notice of that time also noted that Joplin was looking for Mr. Berlin on a certain matter, which may have been concerning the potentially subconscious plagiarism. The issue was never fully resolved, but the facts seem plausible.

Berlin was also utilized to review the works of other composers for publication, and became Snyder's right hand man. One of these composers was Scott Joplin, who in 1911 was shopping his opera Treemonisha around Tin Pan Alley in hopes of getting it in print, and raising money to stage it. There is a good chance that the score came across Berlin's desk. Later in that year with the help of Snyder arranger Alfred Doyle he re-purposed an earlier unsuccessful song, Alexander and His Clarinet, with a new verse, a tune we all now know as Alexander's Ragtime Band. This new verse was highly similar to the original melody of Joplin's A Real Slow Drag which closed the opera. In fact, it was reported by Joplin's surviving wife, Lottie Stokes Joplin, that he likely altered the melody afterwards so it did not match the verse to Alexander's Ragtime Band. A newspaper notice of that time also noted that Joplin was looking for Mr. Berlin on a certain matter, which may have been concerning the potentially subconscious plagiarism. The issue was never fully resolved, but the facts seem plausible.

Berlin was also utilized to review the works of other composers for publication, and became Snyder's right hand man. One of these composers was Scott Joplin, who in 1911 was shopping his opera Treemonisha around Tin Pan Alley in hopes of getting it in print, and raising money to stage it. There is a good chance that the score came across Berlin's desk. Later in that year with the help of Snyder arranger Alfred Doyle he re-purposed an earlier unsuccessful song, Alexander and His Clarinet, with a new verse, a tune we all now know as Alexander's Ragtime Band. This new verse was highly similar to the original melody of Joplin's A Real Slow Drag which closed the opera. In fact, it was reported by Joplin's surviving wife, Lottie Stokes Joplin, that he likely altered the melody afterwards so it did not match the verse to Alexander's Ragtime Band. A newspaper notice of that time also noted that Joplin was looking for Mr. Berlin on a certain matter, which may have been concerning the potentially subconscious plagiarism. The issue was never fully resolved, but the facts seem plausible.

Berlin was also utilized to review the works of other composers for publication, and became Snyder's right hand man. One of these composers was Scott Joplin, who in 1911 was shopping his opera Treemonisha around Tin Pan Alley in hopes of getting it in print, and raising money to stage it. There is a good chance that the score came across Berlin's desk. Later in that year with the help of Snyder arranger Alfred Doyle he re-purposed an earlier unsuccessful song, Alexander and His Clarinet, with a new verse, a tune we all now know as Alexander's Ragtime Band. This new verse was highly similar to the original melody of Joplin's A Real Slow Drag which closed the opera. In fact, it was reported by Joplin's surviving wife, Lottie Stokes Joplin, that he likely altered the melody afterwards so it did not match the verse to Alexander's Ragtime Band. A newspaper notice of that time also noted that Joplin was looking for Mr. Berlin on a certain matter, which may have been concerning the potentially subconscious plagiarism. The issue was never fully resolved, but the facts seem plausible.The chorus of Alexander's Ragtime Band is similarly constructed from existing tunes, including the Reveille bugle call and Stephen Collins Foster's Old Folks at Home (Swanee River). While there is not a lick of actual ragtime syncopation in the piece, it quickly became and has stayed as an anthem of the ragtime era, and it permanently cemented Berlin's name in the songwriting world. The piece was immediately recorded by the Victor Military Band, and even played on the Titanic's maiden (and final) voyage the following year. It has been recorded endlessly by all stripes of music artists, including Ray Charles in a unique arrangement. In the late 1930s a movie was made based on the song. Even in its original printings at least 40 different entertainers were featured on the various covers of the piece. A piano solo version was also available for a while, likely arranged by Doyle. All of this success from one publication, and yet Irving was just beginning his contributions to the Great American Song Book.

With Alexander's Ragtime Band, Berlin readily found the pulse of the American music consumer, and did all he could to feed it. It would be some time before he started turning out his famed romantic ballads, but for now he simply became a song machine, with many songs centered around dance or ragtime. He turned enough ragtime-centric songs to be deemed "King of Ragtime Songs," (which should not be confused with syncopated piano ragtime). Even though there were only a couple of scant mentions of him in the news prior to May of 1911, he was suddenly a big item in music and entertainment stories, and his name remained in the press for decades to come.

In 1911 and 1912 Berlin and Snyder continued to turn out a tidal wave of tunes, and all told there was a new Berlin song every four to five days, an astonishing feat. His output in 1911 and 1912 alone eclipsed that of the lifetime output of most successful ragtime writers and many popular writers as well.

The popularity that Berlin songs were gaining were also very evident to his employer, who had concerns that he would have to either pay more than he could afford to keep Berlin around, or that his new star might jump ship for a better company. The best thing he could do was to offer Berlin a partnership. So on December 13, 1911, Snyder and his financial partner, Henry Waterson, renamed the firm Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, entitling Irving to a share of profits, including from his own substantial works. For many years their office was above the famed Strand Theater in Manhattan. Berlin would remain a publisher to the end of his career.

|

It should be noted that because of his limitations as a pianist, which were extreme in 1911 and 1912, that Berlin never wrote piano ragtime, nor would he write true jazz or stride. He was and would remain a writer of popular songs. However, Irving was in some sense a proponent of ragtime, reporting on it and encouraging it through his songs. During the ragtime era the ratio of popular songs (verse and chorus tunes that were about any number of topics but not classically composed) to rags, or even rags and intermezzos combined, was at least 20 to 1, and maybe higher. So with Alexander's Ragtime Band, That Mysterious Rag, Oh, That Beautiful Rag and similar tunes, Berlin was simply voicing, or in some cases creating more interest in the music. The success of a song was clear even back then. It needs a good topic and a good musical hook that is easy to remember as well as hum. So for capturing the essence of the ragtime era and making it live far beyond its rumored end in the late 1910s, even with limited syncopation in some of his 1910s pieces, Berlin could very much be considered a viable composer of ragtime, even if not piano rags.

Riding high on his successes, Irving gained confidence in himself and his stature as a musician. It should be noted that throughout his career this was never a solo effort, as he never completely gained the necessary skills to notate and arrange his own tunes. With his rudimentary piano skills, which as legend tells it centered around playing the black keys, usually in F# major (unkindly referred to by many as the "nigger key"), he was able to play sufficient melody and chords to get the general notion of a piece across. It may have influenced many of the pentatonic qualities of his early melodies. However, there was usually a ghost writer at his side who turned his ideas into a salable product. Usually in the music industry this person was cited as an arranger, and indeed a few Berlin pieces did have an arranging credit. But for the most part, whether it was initially his decision or that of the other firm's partners, Berlin's name usually stood alone. Among the assistants were composer Cliff Hess, who worked with Berlin from around 1913 to 1918, and later Arthur Johnston, and then Helmy Kresa. In some cases a co-composer credit might have been fitting as they worked out some of the chord changes, but it became a Berlin tradition that if it was his melody it was his song. It also became increasingly clear during 1912 and 1913 that he was better able to fit his own lyrics to a proper melody, and collaborations with a handful of lyricists started diminishing, particularly as his solo efforts flew off the store shelves.

It also became increasingly clear during 1912 and 1913 that he was better able to fit his own lyrics to a proper melody, and collaborations with a handful of lyricists started diminishing, particularly as his solo efforts flew off the store shelves.

It also became increasingly clear during 1912 and 1913 that he was better able to fit his own lyrics to a proper melody, and collaborations with a handful of lyricists started diminishing, particularly as his solo efforts flew off the store shelves.

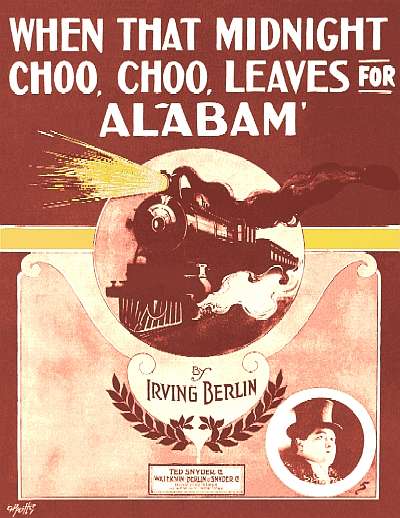

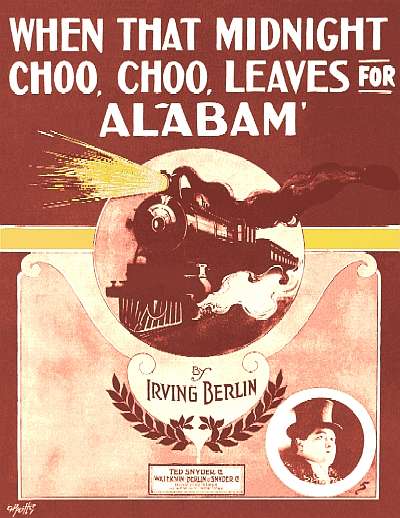

It also became increasingly clear during 1912 and 1913 that he was better able to fit his own lyrics to a proper melody, and collaborations with a handful of lyricists started diminishing, particularly as his solo efforts flew off the store shelves.Irving's induction into ballads came about in a somewhat tragic way. Riding high on the success of his great ragtime hit, Berlin dated Dorothy Goetz, sister of one of his earlier lyricists, E. Ray Goetz, and they married a few weeks later in February of 1912. They took a honeymoon in Cuba where she contracted typhoid fever, finally succumbing to it in June. Berlin was devastated and unsure how to express his grief over the loss. Goetz suggested that he simply write a ballad about his feelings, and When I Lost You became the first of his many heart-wrenching ballads. He would show up as still single on his 1917 draft record, and remained a widower in the 1920 census. However, a tragedy of this proportion would not strike again in his otherwise charmed life.

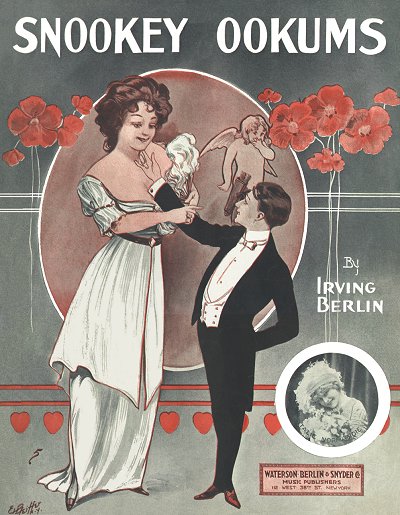

That same year of 1912 he had another monster hit with When That Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam' which quickly found its way to the vaudeville stage, and the following year would yield a number of fine tunes, including the comedy hit Snooky Ookums. On two tunes of that year, published with another firm, he was credited as Ren. G. May, an anagram for Germany, of which the principal city was, of course, Berlin. He also used this credit to record the tunes, still being a pretty fair singer. As for his introduction to Hess in 1913, it set in motion his paradigm of having a personal assistant at his beck and call for most of the rest of his career. Hess had been hired by the Chicago branch of Waterson, Berlin & Snyder as a song demonstrator, and perhaps a copyist as well. It was there he first met his future boss in early 1913, as was later notedas per a later account in an Edison Records flyer advertising Billy Murray's recording of In My Harem.:

Mr. Berlin has had little practical instruction in music, and, although he plays the piano exceptionally well he plays by ear only. At the time "In My Harem" was written, Mr. Hess was working in the Chicago office of the Waterson, Berlin and Snyder Company. Berlin went to Chicago on the 20th Century Limited and worked out this tune in his head while on the train. When in Chicago he played it over (all on the black keys, as he always does) and Mr. Hess sat by him and wrote it down on paper as he played it. This struck the composer as a great time-saving device, for Mr. Hess afterwards transposed it into a simpler key, and arranged it in its less complicated commercial form.

Almost immediately, in early 1913, Hess found himself in Manhattan, having been hired by Berlin as a full-time "private secretary," which really was more like his right hand assistant in regards to Berlin's composing. Up to this point, Irving had engaged other composers or arrangers at associated with Snyder at need in order to help him flesh out his tunes with a simple accompaniment.

This included composers George Botsford, George Meyer and Edgar Leslie. Cliff, however, was the first of a handful of assistants hired specifically to be at Berlin's bidding whenever the muse struck. There was probably a little more to Berlin's need to have Hess around. It would be understandable that the grieving Berlin would want company to keep him distracted. To that end, Hess actually took up residence in Berlin's apartment, and when he wasn't assisting Irving with his latest song, perhaps deciding on the chord progression for a verse or one specific chord change, or tending to the composer's business affairs, he could be heard performing on some of the New York stages, working as an accompanist for some singers, or even writing his own material. But Berlin was the first priority in his life at that time, for which he received an adequate stipend. The sometimes arduous process was described in an article by writer Rennold Wolf in the August, 1913, issue of Green Book Magzine:

|

Hess resides with Berlin at the latter's apartment in Seventy-first Street; he attends to the details of the young song-writers's business affairs, transcribes the melodies which Berlin conceives and plays them over and over again while the latter is setting the lyrics. When Berlin goes abroad Hess accompanies him.

Hess' position is not so easy as it might at first appear, for Berlin's working hours are, to say the least, unconventional. And right here is to be mentioned the real basis of Berlin's success. It is industry—ceaseless, cruel, torturing industry There is scarely a waking minute when he is not engaged either in teaching his songs to a vaudeville player, or composing new ones.

His regular working hours are from noon until daybreak. All night long he usually keeps himself a prisoner in his apartment, bent on evolving a new melody which shall set the whole world to beating time. Much of the night Hess sits by his side, ready to put on record a tune once his chief has hit upon it. His regular hour for retiring is five o'clock in the morning. He arises for breakfast at exactly noon. In the afternoon he goes to the offices of Watterson [sic], Berlin and Snyder and demonstrates his songs.

That Hess could, in some regards, be considered a co-composer of many of the fine Berlin tunes of 1913 to 1918 creates a question without an easy answer in most cases. Yes, he provided some of the harmonic content that supported the melodies, and may have even worked some lyrical alterations by suggestion. But, as with Irving's other long-term assistants, he was paid to write and advise, and the words and music were still Berlin's. Later case law would suggest otherwise, as there were rulings showing that the harmonic direction of a song, such as in the blues, could provide sufficient difference between similar melodic lines, so history would be in favor of Cliff and his successors as per that credit. In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them.

Yes, he provided some of the harmonic content that supported the melodies, and may have even worked some lyrical alterations by suggestion. But, as with Irving's other long-term assistants, he was paid to write and advise, and the words and music were still Berlin's. Later case law would suggest otherwise, as there were rulings showing that the harmonic direction of a song, such as in the blues, could provide sufficient difference between similar melodic lines, so history would be in favor of Cliff and his successors as per that credit. In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them.

Yes, he provided some of the harmonic content that supported the melodies, and may have even worked some lyrical alterations by suggestion. But, as with Irving's other long-term assistants, he was paid to write and advise, and the words and music were still Berlin's. Later case law would suggest otherwise, as there were rulings showing that the harmonic direction of a song, such as in the blues, could provide sufficient difference between similar melodic lines, so history would be in favor of Cliff and his successors as per that credit. In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them.

Yes, he provided some of the harmonic content that supported the melodies, and may have even worked some lyrical alterations by suggestion. But, as with Irving's other long-term assistants, he was paid to write and advise, and the words and music were still Berlin's. Later case law would suggest otherwise, as there were rulings showing that the harmonic direction of a song, such as in the blues, could provide sufficient difference between similar melodic lines, so history would be in favor of Cliff and his successors as per that credit. In the end, while some of Cliff's contributions are evident to even amateur Berlin scholars, including the piano accompaniment, other facets are hard to separate from between the pair. Indeed, in spite of the output of Hess compositions, with more than two dozen other writers, Berlin's name does not appear with his on any one of them.As far as the effectiveness of their methodology for turning out popular tunes in short order, Irving demonstrated this ability during a trip to England to perform at the Hippodrome, as recounted in the Music Trade Review of July 12, 1913:

WRITING RAGTIME TO ORDER.

Irving Berlin Gives Representative of London Newspaper Interesting Demonstration of the Manner in Which He Dashes Off Hits in Record Time.

Irving Berlin Gives Representative of London Newspaper Interesting Demonstration of the Manner in Which He Dashes Off Hits in Record Time.

With the ragtime craze at its height in England, the recent arrival of Irving Berlin, the successful song writer and exponent of that form of melody, created about as much interest as would a visit from the head of one of the reigning houses on the Continent.

Following the stories from New York regarding Mr. Berlin's ability to dash off a song and sell it for a couple thousand dollars, all in a few minutes, a representative of the Daily Express, of London, called on him for a practical demonstration, and from it wrote the following story:

"Upon receiving the request for a song to order, Mr. Berlin said:

"'Usually, I get my rhythm and melody complete before I give them to the "arranger." This is a pretty hard test, but I'll try.'

"He did. He walked about four miles doing it, in the course of two hours. He was never still a moment. "At the finish a new ragtime had grown before its listeners, all complete, from the introduction and vamp to the final chord of the chorus. Afterwards he made up the words.

"This is how he did it. The 'arranger' [Cliff Hess] sat at the piano, pencil and paper ready. Irving Berlin started a one-step up and down the room, snapping his fingers and jerking his shoulders as he went. He did this for some time. It was the divine afflatus on marionette wires.

"Suddenly he stopped, leaned over the 'arranger,' and 'La-ta-ta-ta-tatata,' he began. 'That's the

opening line.'

"The 'arranger' wrote down the precious notes and played them.

"'Fine,' said Irving Berlin; and off he went again, up and down, to and fro, dancing a one-step to imaginary tunes rollicking through his mind.

"'Play it again,' he said, with a snap of his fingers. A minute passed. Irving Berlin clapped his hands to his ears and changed the direction of his walk. It came slowly, but when it did come there was a burst of half a dozen bars.

"So, gradually, the ragtime is built up."

'Play it once more. I want to get back to the key,' he says, after a half-hour's ineffectual lum-tum-tums.'

"Finally, the chorus, the most difficult of all. It has to be catchy, it has to trip and slide, and stop, and drop from key to key and be lifted back again. It has to 'go.'

"With a rush the thing is finished. It has been fitted together like a puzzle, intricate little pieces of melody running haphazard nowhere and fading abruptly as other strains follow, with just a semblance of the motif to keep it together."

The title of the on-the-spot song was "That Humming Rag." By the end of the hour it was evident to the press that Cliff Hess might have been the real talent in the room, and some items were published suggesting that Berlin was perhaps not so talented after all, barely able to play and unable to notate. Actually, this incident could have gone another way, and with the help of his loyal secretary, he managed to found a way out. When trying to plan his subsequent performance at the London Hippodrome the next day, and overcome any potential bad press all at once, Irving came to the conclusion that all of his existing material had already been spread around London, and that he needed something new as a diversion. With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.

barely able to play and unable to notate. Actually, this incident could have gone another way, and with the help of his loyal secretary, he managed to found a way out. When trying to plan his subsequent performance at the London Hippodrome the next day, and overcome any potential bad press all at once, Irving came to the conclusion that all of his existing material had already been spread around London, and that he needed something new as a diversion. With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.

barely able to play and unable to notate. Actually, this incident could have gone another way, and with the help of his loyal secretary, he managed to found a way out. When trying to plan his subsequent performance at the London Hippodrome the next day, and overcome any potential bad press all at once, Irving came to the conclusion that all of his existing material had already been spread around London, and that he needed something new as a diversion. With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.

barely able to play and unable to notate. Actually, this incident could have gone another way, and with the help of his loyal secretary, he managed to found a way out. When trying to plan his subsequent performance at the London Hippodrome the next day, and overcome any potential bad press all at once, Irving came to the conclusion that all of his existing material had already been spread around London, and that he needed something new as a diversion. With the dutiful Hess at his side, they worked far into the night, having to mute the piano in the hotel room at the Savoy as best they could using bath towels to address complaints from other guests, and had at least half of That International Rag completed by sunrise. Before show time the song was completed and Berlin had it memorized. Berlin sang this piece in a modest tone with Hess at the piano, and quickly silenced the critics while engaging the audience with something new and effective. With Cliff's support, and yet while keeping him in the background, Berlin triumphed over the British, and then Europe, and never looked back. Like his other "rag" songs, there was virtually no "ragtime" in That International Rag other than the word "rag," but with Cliff's peppy accompaniments, the melodic issues in terms of the lack of syncopation were readily overcome.While popular songs and ragtime-oriented and dance tunes were helping Berlin make his name, there was another inevitability awaiting him, and it was literally just up the street from his office.

Broadway Beginnings

Almost since his collaboration with Snyder began, Irving Berlin songs had found their way into shows on Broadway and 42nd Street through interpolation, and given his past dealings with Tony Pastor he was no stranger to the stage either. However in 1914, Berlin finally released one of the first ragtime-based (more in name than in style) musicals (by today's standards musicals of that time would be considered revues) on Broadway. Few stage musicals at that time, perhaps with George M. Cohan's (who wrote a song lauding Irving Berlin melodies a year later) being the exception, had songs by any one composer, but Berlin did provide the majority of them for Watch Your Step. His original stated intent was to write a "ragtime opera," although he ended up with a pretty decent revue featuring some syncopation and lots of dancing.

had songs by any one composer, but Berlin did provide the majority of them for Watch Your Step. His original stated intent was to write a "ragtime opera," although he ended up with a pretty decent revue featuring some syncopation and lots of dancing.

had songs by any one composer, but Berlin did provide the majority of them for Watch Your Step. His original stated intent was to write a "ragtime opera," although he ended up with a pretty decent revue featuring some syncopation and lots of dancing.

had songs by any one composer, but Berlin did provide the majority of them for Watch Your Step. His original stated intent was to write a "ragtime opera," although he ended up with a pretty decent revue featuring some syncopation and lots of dancing.For the debut Berlin and his producers already had an ace in the hole, utilizing the recent popularity of the famous dancing couple Vernon and Irene Castle as his stars. Taking some queues from the Ziegfeld Follies, there were even some extravagances displayed on the stage, including a sizable medley of popular opera themes with some syncopation added. The combination of talents in the show made it a great success, and it played initially for 175 performances, a good run at that time. Most of the songs also ended up in print and were sold in the lobby as well as in stores, an added bonus. For the purposes of publishing this show the composer formed his own company, Irving Berlin, Inc., but still remained with Waterson and Snyder who published his popular tunes. One of the tunes in this show quickly gained hit status and eventually became a standard, the finely double-layered Simple Melody (later renamed Play a Simple Melody). The following year he contributed the majority of pieces for Stop! Look! Listen!, which ran for a respectable 105 performances. The standout hit of that show, still with us today, was I Love a Piano, reportedly his favorite tune of all time.

After a rather uneventful, and somewhat less prolific year in 1916, Berlin contributed to another show in 1917, Dance and Grow Thin, and tackled the latest musical craze - jazz - with some supposed jazz of his own. The word, which had proliferated into popular usage from late 1916 on, was new, but many song titles started featuring it, including Berlin's own Mister Jazz, Himself. He then did a rare collaboration with the other more established big fish in the Broadway pond, George M. Cohan, and their co-written The Cohan Revue of 1918 previewed on New Year's Eve and ran for 96 performances. Berlin also published the bulk of Cohan's pieces from this period.

Some time before that, not yet a U.S. Citizen, Irving was drafted into the United States Army late in 1917, and assigned to Camp Upton at Fort Yiphank. He very quickly took advantage of this situation by writing about it, one of the earliest pieces being a protest song (especially for the musician's lifestyle), Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning. In an effort to keep to his true talent, he persuaded the brass to let him stage an Army-based show utilizing enlisted men, and they agreed. Now not having to keep to regulation hours, Berlin completed Yip Yip Yiphank and staged 32 performances of it utilizing 350 troops. While there was no Over There embedded in the work, two of the songs went on to become big standards, one of them held back for two decades. Mandy, which many associate with the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919, was actually first heard in the Army show, but retooled a year later.

While there was no Over There embedded in the work, two of the songs went on to become big standards, one of them held back for two decades. Mandy, which many associate with the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919, was actually first heard in the Army show, but retooled a year later.

While there was no Over There embedded in the work, two of the songs went on to become big standards, one of them held back for two decades. Mandy, which many associate with the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919, was actually first heard in the Army show, but retooled a year later.

While there was no Over There embedded in the work, two of the songs went on to become big standards, one of them held back for two decades. Mandy, which many associate with the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919, was actually first heard in the Army show, but retooled a year later.However, a more somber tune which was prepared for the Army show ended up being pulled, perhaps even before the first performance. It would not be until 1938 that Berlin would pull out the everlasting God Bless America for its first public performance by singer Kate Smith on Armistice Day of that year. It has since become the most revered and most sung tune in America composed by a Russian Jew simply trying to survive the army. The publications of Yip Yip Yiphank were printed with his promotion clearly shown, composed by Sergeant Irving Berlin. On February 6, 1918, Irving Berlin became a naturalized citizen of his adopted country.

Since Irving ended up not actually going into combat he was able to maintain a good songwriting pace, and soon after the war he increased the scope of his own firm, taking on works by other composers as well, finally leaving Waterson, Berlin & Snyder at the end of 1918. In 1919 Florenz Ziegfeld, no stranger to Berlin tunes, asked him to contribute as much as he could to that year's Follies. Along with a revamped version of Mandy he came up with what would become the signature Ziegfeld anthem, A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody.

In the January 1920 census he is shown as a widower living in Manhattan with a secretary and a housekeeper, his occupation as an author of songs. That same year, Berlin similarly contributed a bounty of tunes to Ziegfeld for the 1920 Follies, but he had something else in the works. Carefully using his considerable profits from his musical endeavors, Berlin decided to exercise more control over the environment that his musicals would be in, as well as the availability of a place to stage him, and along with his new partner Sam Harris financed the construction of his own 1025 seat Music Box Theater on 45th Street. The opening show there was his Music Box Revue of 1921 which ran for a rather astonishing (at that time) 440 performances. Three more similar revues were staged over the next four years, each with declining attendance and shorter runs, although still far from tepid. The last of these Music Box Revues in 1925 featured Fannie Brice, but ran for only 194 performances.

The Music Box Theater remained busy with other productions that leased it, and is still in business in the 21st century. In 2007 ownership passed from the Berlin estate to the Shubert Theater Organization.

The majority of Berlin's song output from this period was what was featured in the Revues, but there were some notable exceptions. He was also able to use his name as leverage on the covers, many of the titles starting with his name, such as "Irving Berlin's All Alone," something most publishers shied away from. But they weren't publishing such the most prolific songwriter of the age either.

|

In 1924 Irving started to date socialite Ellin Mackay, 15 years younger than himself, who would become his second wife. But there seemed to be many obstacles in the way of his convincing her to marry him. Among them, his Jewish heritage and upbringing in poverty, contrasted with the fact that she was a devout Irish-American Catholic and heiress to the Comstock Lode mining fortune. Some of his more stirring ballads came as a direct result of songs he wrote for Ellin, including All Alone, Remember, and the wistful weeper What'll I Do. Finally he won her with singing (a plot theme repeated in the movie Holiday Inn several years later), and just before they were married in January of 1926 he wrote the simple and elegant Always for her as well, assigning all of the (considerable) income from the song to Ellin. She was immediately disinherited by her father, and for a time they were snubbed by many members of society for the inter-faith marriage. Irving and Ellin had a daughter, Mary Ellin, within the year. Linda Emmett and Elizabeth Peters would follow, as would Irving Berlin Jr. who would sadly die in childbirth.

Following the traveling patterns of Berlin throughout the 1920s, particularly after marrying Ellin, becomes quite an endeavor, since he is listed on dozens of ship manifests going to Europe, the United Kingdom, the Bahamas, Hawaii, and other exotic ports of call. Berlin liked cruises, but when called upon to perform or accompany (as best he could) on these trips he was often stymied by his F# playing. So he had either four or five special transposing pianos built for him which allowed the keys to slide back and forth underneath the action, facilitating his playing in a suitable key for any occasion. One of these usually accompanied him on a cruise ship, one in the theater, one at the office, one at home, and there may have been a spare. One of these unique pianos resides today in the American History collection of the Smithsonian Institution.

Irving's cleverness would pay off for both him and a group of brothers looking for a vehicle that would exploit their singularly unique talents. So in 1925, based on a book by playwright Irving Kaufman, he came up with a nearly schizophrenic set of songs for The Cocoanuts starring the Marx Brothers in their recently redefined personas as Groucho, Chico, Harpo, Zeppo and Gummo. The first incarnation would run 276 performances, with the brothers constantly adjusting the material to the point where it worked flawlessly. It was revived in 1927 with an additional tune for another healthy run, cementing their inevitable success.

Berlin's biggest song of 1926 would turn out to be Blue Skies, soon to become a standard through the voice of a new kid on the block, crooner Bing Crosby, who would be a great proponent of Berlin songs. His final contribution to the stage in the 1920s was for the 1927 Ziegfeld Follies, one of the most ambitious years of Ziegfeld's career in which the entrepreneur staged four shows at one time. That same year brought the beautiful instrumental Russian Lullaby. However, through Bing and the Max Brothers and other connections, a new medium was soon to call for the great Berlin.

Hollywood, Then Back to Broadway

While Berlin songs sold well throughout the country, they were mostly performed live in New York through the 1920s. However, in 1927, as synchronized sound film became a possibility, a Vitaphone short came out called The Little Princess of Song starring 13-year-old Sylvia Froos, singing Blue Skies. There was enough interest in the piece that Al Jolson, no stranger to Berlin songs by this time, used it for his pivotal "live dialog" scene in The Jazz Singer shortly thereafter, with Bert Fiske playing an offstage piano while Jolson mimed his own playing. The movie, that scene in particular, was a sensation, and Blue Skies certainly did not suffer. It went on to be heard on recordings and in movies a panoply of styles, including one 21st (or 24th) century rendition by singer/actor Brent Spiner as Data in the tenth Star Trek movie. But it also meant that Berlin songs could potentially be heard virtually anywhere as performed by stars of the screen. In the early days of sound when dialog was still difficult to capture, but music was much easier to record, many of the earliest sound films became musicals, and they drew on whatever they could find in order to both have new material and capitalize on the subsequent sales of sheet music or records. Berlin was happy to oblige this new trend, and stepped up to the plate.

The movie, that scene in particular, was a sensation, and Blue Skies certainly did not suffer. It went on to be heard on recordings and in movies a panoply of styles, including one 21st (or 24th) century rendition by singer/actor Brent Spiner as Data in the tenth Star Trek movie. But it also meant that Berlin songs could potentially be heard virtually anywhere as performed by stars of the screen. In the early days of sound when dialog was still difficult to capture, but music was much easier to record, many of the earliest sound films became musicals, and they drew on whatever they could find in order to both have new material and capitalize on the subsequent sales of sheet music or records. Berlin was happy to oblige this new trend, and stepped up to the plate.

The movie, that scene in particular, was a sensation, and Blue Skies certainly did not suffer. It went on to be heard on recordings and in movies a panoply of styles, including one 21st (or 24th) century rendition by singer/actor Brent Spiner as Data in the tenth Star Trek movie. But it also meant that Berlin songs could potentially be heard virtually anywhere as performed by stars of the screen. In the early days of sound when dialog was still difficult to capture, but music was much easier to record, many of the earliest sound films became musicals, and they drew on whatever they could find in order to both have new material and capitalize on the subsequent sales of sheet music or records. Berlin was happy to oblige this new trend, and stepped up to the plate.

The movie, that scene in particular, was a sensation, and Blue Skies certainly did not suffer. It went on to be heard on recordings and in movies a panoply of styles, including one 21st (or 24th) century rendition by singer/actor Brent Spiner as Data in the tenth Star Trek movie. But it also meant that Berlin songs could potentially be heard virtually anywhere as performed by stars of the screen. In the early days of sound when dialog was still difficult to capture, but music was much easier to record, many of the earliest sound films became musicals, and they drew on whatever they could find in order to both have new material and capitalize on the subsequent sales of sheet music or records. Berlin was happy to oblige this new trend, and stepped up to the plate.The Cocoanuts finally made it to film via Paramount in 1929, but more than half the tunes were cut from the movies, because without intermissions like live stage shows, people seemed less likely to sit through a full two hour production. However, MGM and other studios would eventually find a way to pack almost as much music into a film as a stage production, often focusing on a single composer for those films. One Berlin song composed in 1929 for a film released in 1930 would actually have four more resurgences over the next few decades, and is clearly an exciting standard today. Written just ahead of the depression, Puttin' On the Ritz (for the film of the same name) combined ragtime and jazz with danceability in a song about snooty rich people. It was retooled in 1946 for Fred Astaire in the movie Blue Skies, becoming much more popular with the newer lyrics. Mel Brooks made it a centerpiece of his 1974 film Young Frankenstein, and later in 2007 as a huge production number for the stage version of the story. And in the early 1980s Danish singer called Taco Ockerse made it into a techno-pop retro-hit in Europe and the United States.

In 1929 ragtime veteran Al Jolson asked for more material for his new film career, and ended up with five new Berlin songs in My Mammy, released 1930. One more film keeping Irving busy was Hallelujah with another pair of songs. While traveling to Hollywood to facilitate the incorporation of his tunes into film from time to time, Berlin still stayed firmly based in Manhattan while not off on a cruise ship. He is shown there in the 1930 census with Ellin and Mary Ellin, a self-employed composer of music.

Notable films over the next decade that would feature Berlin music include Top Hat (1935), featuring Cheek to Cheek; Follow the Fleet (1936), featuring Let's Face the Music and Dance; the all-Berlin film On the Avenue (1937); another Berlin song extravaganza filled with ragtime-era classics

- Alexander's Ragtime Band (1938); and Carefree (1938). At least a dozen more films of the decade featured Berlin pieces, old and new, albeit in a less musical context. Yet Irving remained dedicated to the live stage as well.

|

Broadway took quite a hit during the Great Depression as it was much less expensive to create and distribute a film than it was to employ fifty or more people every night for a stage production. So some of them were scaled back or less performances held. Just the same, there were enough people in Manhattan well enough off and in need of entertainment that the producers pressed on, including Berlin and Harris. In 1932 he came out with the political satire Face the Music, and the following year with a play lauding the new president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in As Thousands Cheer, a play in which cast members played several different roles, perhaps a cost-cutting measure. This show ran more than a year, achieving 400 performances in the first run. It also had an embedded tune called Heat Wave which found plenty of favor in the 1950s when sexy new star Marilyn Monroe infused new meaning into it.

Another piece, which started out in 1917 as Smile and Show Your Dimples, was retooled with the same melody into the piece Her Easter Bonnet. It eventually found success when it was later retitled as Easter Parade, although it took five film appearances before the piece would take off. Berlin's publishing empire remained consistent and busy throughout the 1930s as well, and he had the good fortune to have been contracted by Walt Disney to put many of that studio's works into print, including all of the songs from the stellar hit, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and later Pinocchio and Dumbo.

The face of Broadway would change in the wake of musicals such as Snow White and The Wizard of Oz where gradually the songs featured in these stories would actually be part of the story, forwarding the plot, rather than just assembled for the sake of putting a song at a certain point in the story. Many consider the dawn of the modern musical to be Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma in 1943, and it does contain the elements of character-based songs that have more context within the story than if sung alone. However, Berlin approached this concept fairly successfully in 1940, at age 52, with the satirical comedy Louisiana Purchase, a similar idea to that of Oklahoma. It ultimately ran a respectable 444 performances, and in 1941 was made into a less than successful Paramount film with Bob Hope in the lead. Given the tone of the musical and the story emphasis on the songs, it yielded no lasting hits. In the 1940 census the Berlin family was living together in Manhattan, including Ellen, and their daughters Mary Ellen (13), Linda L. (8) and Elizabeth I. (3). They also had 1 live-in nurse and four servants. In spite of how well things were going for the other composer, there were other worries in the world at that time, and they came to a head in December of 1941 with the American entry into World War II. Again, Sergeant Irving Berlin would be there to rally for the cause.

The Berlin Renaissance