J. Bodewalt Lampe wielded perhaps more influence over music of the 1900s and 1910s as an arranger as he did in his capacity as a composer, and some of his arrangements of classic melodies into songs helped keep them alive well into the 21st century. Jens was born to concertmaster/musician Christian Lampe and his wife Sophia Dorothea Nielson in Ribe, Denmark (a name he would later alter and use as a pseudonym). The Lampe family arrived in the United States on September 25, 1873, with Christian listing himself as a bookmaker (book binder), likely a steadier career track for an immigrant. Soon after they settled for a while in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was here that Christian's musical experience put him in leadership of the notable Great Western Band founded in 1867, a touring group made up initially of European musicians, largely of Bohemian export, which continued well into the twentieth century.

The Lampe family arrived in the United States on September 25, 1873, with Christian listing himself as a bookmaker (book binder), likely a steadier career track for an immigrant. Soon after they settled for a while in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was here that Christian's musical experience put him in leadership of the notable Great Western Band founded in 1867, a touring group made up initially of European musicians, largely of Bohemian export, which continued well into the twentieth century.

The Lampe family arrived in the United States on September 25, 1873, with Christian listing himself as a bookmaker (book binder), likely a steadier career track for an immigrant. Soon after they settled for a while in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was here that Christian's musical experience put him in leadership of the notable Great Western Band founded in 1867, a touring group made up initially of European musicians, largely of Bohemian export, which continued well into the twentieth century.

The Lampe family arrived in the United States on September 25, 1873, with Christian listing himself as a bookmaker (book binder), likely a steadier career track for an immigrant. Soon after they settled for a while in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was here that Christian's musical experience put him in leadership of the notable Great Western Band founded in 1867, a touring group made up initially of European musicians, largely of Bohemian export, which continued well into the twentieth century.Jens, J.B., as he was often called, was a child prodigy, particularly on the violin. He also quickly took to trombone, cornet, clarinet, piano, and many other orchestral instruments. In addition to occasional performances with Great Western, he became the first chair violinist for the Minneapolis Symphony at age 16, having trained with Frank Danz. Jens was academy trained in further music instruction. While receiving his training in Chicago around 1888 J.B. met and married Illinois native Josephine H. Dell. Their first child, Walter Lee, was born the next year in Chicago. The couple moved to Buffalo at some point in the 1890s. That is where the couple's daughter Petra M. was born in 1893, as was their son Joseph Dell in 1895, and daughter Dorothy H. in 1897. Jens' father Christian and much of the family remained in Minnesota until after 1900, after which the elder Lampe moved to Atlantic City where he would lead many bands for the remainder of his life. Jens and his brood were shown in Buffalo in the 1900 census with Jens listed as a musical director, and a naturalized citizen, likely through his father's naturalization.

The couple moved to Buffalo at some point in the 1890s. That is where the couple's daughter Petra M. was born in 1893, as was their son Joseph Dell in 1895, and daughter Dorothy H. in 1897. Jens' father Christian and much of the family remained in Minnesota until after 1900, after which the elder Lampe moved to Atlantic City where he would lead many bands for the remainder of his life. Jens and his brood were shown in Buffalo in the 1900 census with Jens listed as a musical director, and a naturalized citizen, likely through his father's naturalization.

The couple moved to Buffalo at some point in the 1890s. That is where the couple's daughter Petra M. was born in 1893, as was their son Joseph Dell in 1895, and daughter Dorothy H. in 1897. Jens' father Christian and much of the family remained in Minnesota until after 1900, after which the elder Lampe moved to Atlantic City where he would lead many bands for the remainder of his life. Jens and his brood were shown in Buffalo in the 1900 census with Jens listed as a musical director, and a naturalized citizen, likely through his father's naturalization.

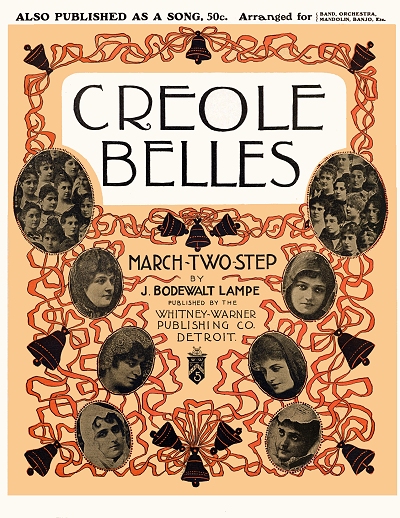

The couple moved to Buffalo at some point in the 1890s. That is where the couple's daughter Petra M. was born in 1893, as was their son Joseph Dell in 1895, and daughter Dorothy H. in 1897. Jens' father Christian and much of the family remained in Minnesota until after 1900, after which the elder Lampe moved to Atlantic City where he would lead many bands for the remainder of his life. Jens and his brood were shown in Buffalo in the 1900 census with Jens listed as a musical director, and a naturalized citizen, likely through his father's naturalization.J.B.'s first two compositions came out in Buffalo under the label of The Lampe Music Company, the second being a march written for a local newspaper, the Buffalo News. He also arranged and published a small quantity of works by other Buffalo composers, one of them being the unusual The Pork Packer's Daughter by Carrie Pratt. His logo was cleverly based on his last name, an oil lamp with notes popping out of the flame outlet. Then in 1900, Lampe self-published his most enduring hit, Creole Belles, a cakewalk which came near the latter part of popularity for that dance, but with a chorus melody in the B section that would easily remember and often emulated. It was quickly picked up by Whitney-Warner publishers in Detroit due to recordings by no less than John Philip Sousa's band under co-leader Arthur Pryor. As was the vogue with early cakewalks, a song version soon followed. Whitney Warner in turn was folded into the new firm of Jerome H. Remick & Company, and they published subsequent editions from 1905 on. Through the fame from the highly melodic Creole Belles and his proven abilities as a conductor and arranger, Lampe found work as a professional arranger with Whitney Warner, then with the Richmond Music Company, a New York City music jobber.

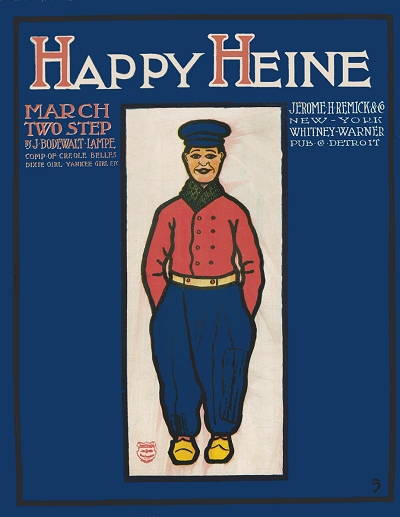

By 1904, with a few other marches and syncopated pieces under his belt, Lampe was pulled to New York to work for Remick, by now the predominant publisher of popular rags and songs, and remained there for nearly two decades. It is also where he and Josephine raised their children Walter, Petra, Dorothy, and most importantly, Joseph Dell, who would one day be his father's employer. In August 1907 Lampe purchased a spacious home at the corner of Petersville Road and Grant Street, Stephenson Park, New Rochelle, just off the Long Island Sound. While employed primarily as an arranger, soon to head that department for the publisher, he also managed to turn out some fine marches and lightly syncopated pieces. Among his more popular entries acquired by Remick were Dixie Girl, Happy Heine, and The Yankee Girl, the latter likely a nod to a popular logo for a tobacco product of that era which may have itself been inspired by a successful Colorado mine. The Happy Heine name was soon conveyed to race cars, boats, and the piece was even adopted by the 18th Infantry Regiment soon after they returned from duty in the Philippine Islands in 1905.

While working for Remick, Lampe was responsible for putting palatable arrangements into the hands of not only the general public, but a number of working musicians as well. Among his efforts included folios of dance music, the popular Star Dance Folios from 1907 on, and of film music as well for theater pianists. He also had a knack for popularizing semi-classical or exotic pieces, among them being Song of India (which would later become a big-band hit), March of the Wooden Soldiers, and Aloha Oe, the latter which predicated a long-lasting craze for Hawaiian tunes and a ukulele in every parlor. This extended to the folios, which included Songs of Scotland and Songs of Ireland in the 1910s. J.B. further touched and fine-tuned many piano rags and ragtime-era works by composers including Charles Daniels, George Botsford, Jean Schwartz, Egbert Van Alstyne, George W. Meyer, Fred S. Stone (also a fine arranger and bandleader), and even a composition by future arranger Ferdé Grofé.

the popular Star Dance Folios from 1907 on, and of film music as well for theater pianists. He also had a knack for popularizing semi-classical or exotic pieces, among them being Song of India (which would later become a big-band hit), March of the Wooden Soldiers, and Aloha Oe, the latter which predicated a long-lasting craze for Hawaiian tunes and a ukulele in every parlor. This extended to the folios, which included Songs of Scotland and Songs of Ireland in the 1910s. J.B. further touched and fine-tuned many piano rags and ragtime-era works by composers including Charles Daniels, George Botsford, Jean Schwartz, Egbert Van Alstyne, George W. Meyer, Fred S. Stone (also a fine arranger and bandleader), and even a composition by future arranger Ferdé Grofé.

the popular Star Dance Folios from 1907 on, and of film music as well for theater pianists. He also had a knack for popularizing semi-classical or exotic pieces, among them being Song of India (which would later become a big-band hit), March of the Wooden Soldiers, and Aloha Oe, the latter which predicated a long-lasting craze for Hawaiian tunes and a ukulele in every parlor. This extended to the folios, which included Songs of Scotland and Songs of Ireland in the 1910s. J.B. further touched and fine-tuned many piano rags and ragtime-era works by composers including Charles Daniels, George Botsford, Jean Schwartz, Egbert Van Alstyne, George W. Meyer, Fred S. Stone (also a fine arranger and bandleader), and even a composition by future arranger Ferdé Grofé.

the popular Star Dance Folios from 1907 on, and of film music as well for theater pianists. He also had a knack for popularizing semi-classical or exotic pieces, among them being Song of India (which would later become a big-band hit), March of the Wooden Soldiers, and Aloha Oe, the latter which predicated a long-lasting craze for Hawaiian tunes and a ukulele in every parlor. This extended to the folios, which included Songs of Scotland and Songs of Ireland in the 1910s. J.B. further touched and fine-tuned many piano rags and ragtime-era works by composers including Charles Daniels, George Botsford, Jean Schwartz, Egbert Van Alstyne, George W. Meyer, Fred S. Stone (also a fine arranger and bandleader), and even a composition by future arranger Ferdé Grofé.At night Lampe led bands or created and directed musical programs for public parks, private parties, hotels, opera houses, and theaters, all while working his way up to a managerial position with Remick. If that's not enough, Lampe contributed either arrangements or compositions to a number of well-known musicals of the 1900s through the early 1920s, including The Chocolate Soldier by Oscar Strauss, Baron Trenck - The Pandour by Felix Aldini, Honeydew by Efrem Zimbalist, and the popular Passing Shows of 1919 and 1921. There were periods when he would get on the road and tour with Lampe's Grand Concert Band, and even plied his talents as a church organist now and then.

While many composers used pseudonyms, they did not often apply those to arranging credits. However, Lampe did both, applying an alteration of the name of his birth place to become Ribé Danmark, under which he first composed the effective and ebullient Glad Rag in 1910, and which appeared on scattered publications from Remick for a decade. His take on the Turkey Trot was performed throughout the country, helping keep the animal dance craze very much alive. Among his more innovative entries was A Vision of Salome composed specifically for Isadora Duncan who was performing the Dance of the 7 Veils regularly. Many of his pieces quickly found their way to cylinders and discs, further spreading knowledge of his name among musicians and the public.

In an extensive and enlightening article in the December 12, 1914 edition of The Music Trade Review, J.B. contributed an somewhat revealing article on music arranging. Given the merits of the text and the insight it gives into not only Remick but the core of the music industry in general, it was deemed worthwhile to quote the majority of it here.

If we go back a few years there was a time when popular music publishers did not believe it necessary to have their publications properly edited; and a composer who could arrange his own music was looked upon with more or less suspicion. There were also a number of superstitions connected with the publishing of popular music. For instance, they would have nothing published in the key of D as that key was considered a "Jonah," and in the case of a song being rushed upon the market before it had been proof-read, on its proving a hit, the publishers would never correct it, as that also was considered unlucky.

Some composers still believe that the editor would spoil their works, which accounts for much of the trash on the market to-day. It is possible that this belief is due to the class of musicians with whom the publishers did business,

whose knowledge was confined to the most elementary rules of harmony and composition. A thorough knowledge of musical science does not hamper or limit the composer, as is believed by so many; on the contrary it enlarges his scope and gives him unlimited resources.

|

Jerome H. Remick & Co., I believe, were one of the first publishers to see the advantage of their publications carefully edited before placing them on the market, as it had been observed that there has never been a hit which did not have real musical merit.

Very few of the popular composers know anything about the theory of music. When one of our composers get an idea for a song or instrumental number as soon as it is sufficiently completed to be taken down, we turn him over to one of our arrangers. The arranger takes down the composition just as the composer plays it, both melody and accompaniment, whether the harmony is correct or not. Then we revise it, putting it into correct musical form, adjust the lyric to the melody in case of a song, and it is then ready for publication. After it has been accepted the order comes to put the number into work. We send the music to our engravers, and in a short time we get back proofs of the plates, which we correct and at the same time we order a title page. The artist then presents us with a sketch and afterwards a drawing of something that will be appropriate for a title page, which is then made into plates. A high-class song would not have a highly colored title page, nor would we put a plain black and white title page on a popular song. At the present time the vogue seems to be something in three or four colors for a popular song.

The professional department then begins working on the song, and we get out professional copies which are given to the performers. We arrange and print vocal orchestrations in from three to seven keys of each song. If it is a good seller we make dance arrangements of it for band and orchestra. It then follows, of course, that we arrange it for vocal quartet, male, mixed and female trios, duets, mandolin, guitar and banjo, etc.

In the arranging room, of which F. C. Collinge is the head, are mostly copyists, only one or two arrangers staying there in case of emergency. Most of our arrangers take their work home, preferring to work in the quietness of their own studios. Among our staff of arrangers are the following well-known musicians: Hugo Frey, James C. McCabe, Wm. J. C. Lewis, Ribe Danmark [Lampe, himself, of course] and others…

The matter of pay for the arranging and copying of music has always been a problem. Years ago we had a flat rate, as for example, we paid a certain sum for an orchestration arrangement consisting of ten parts and piano;

but, it must be considered that when one song is short and simple and the other one is long and difficult, this method of payment is unfair to the man arranging a long song. We finally evolved the system of paying by the actual number of measures in a composition on the basis I mentioned. A good copyist makes from 50 to 75 cents per hour, according to his speed, while an arranger earns from 75 cents to $1.25 per hour.

|

We keep the originals in our library of every song or piece, and we arrange that the house also has a copy of everything that is published. These are numbered and entered into a book. Our librarian knows the compositions by their number and can put her hands on any of them at a moment's notice.

The fact that there is no piano or other musical instrument of any kind in the arranging department has always been a matter of comment by our visitors. Our explanation is that we arrange by rule and not by ear. To get arranging experience a musician must spend a certain number of years in an orchestra, otherwise his knowledge for arranging will only be in the abstract and not in the concrete. There are two elements entering into arranging — instrumentation and orchestration. Instrumentation is the acquiring of a correct knowledge of all the instruments, their limits, their possibilities and their relation to the other instruments. Orchestration is the art of knowing how to devise parts for these instruments to a given musical composition. A thorough knowledge of harmony is necessary to the arranger.

We have recently been engaged in the compiling of music particularly adaptable for photo-plays with the music carefully arranged to follow the film and composed to order when necessary. We are making a careful study of this new field and believe that it has unlimited possibilities. In this department have been made also the orchestrations for the larger part of New York biggest musical productions, such as "The Chocolate Soldier," "Adele," "The Midnight Girl," "Ziegfeld's Follies," "Little Boy Blue," etc.

I need hardly say here that the style in music changes as frequently as the fashions. For instance, the coon songs which were in such vogue several years ago are now no longer popular. At the present time we are having what might be called the conversational song, and the one-step song. The former is the music that is now being used with the popular fox trot. The one-step can be traced back to the beginning of music. Marching and walking are natural movements, and while other rhythms may come and go, this movement will always remain, although its name changes every once in a while.

The notion of having no pianos in the arranging room contrasted greatly with the very paradigm of composers and arrangers pounding on pianos, which is allegedly what gave Tin Pan Alley its name. However, it spoke well of the inherent musicianship of those working with Lampe. As promised, folios of film music were issued starting in 1914 from Jerome Remick, which much of the music directly edited or even composed by Lampe. He was also one of the founding charter members of ASCAP, which established their initial membership on March 24, 1914.

In the mid-1910s, J.B. sent his younger son Joseph Dell, who would later be known as just Dell, to Germany to study music. Dell Lampe would return to become a bandleader in his own right before the 1910s were through. He was back in the United States by 1917, and on his draft record showed Jerome H. Remick as his employer, working as a music editor, probably under his father's supervision.

|

Throughout the 1910s Lampe performed at company events and many charitable functions as well, including some with his wife and daughters on vocals. On October 27, 1918, the Lampe family suffered the loss of their son Walter in a Manhattan hospital. He had been in an army camp a few days prior, so the potential cause of death might have been due to the Spanish flu pandemic which was starting to overspread the globe at that time. Nine days later, a grieving Josephine, who had contracted the deadly flu, passed in a hospital in the Bronx. Overwhelmed by this level of tragedy, Lampe stopped playing publicly, eventually retreating to his office to turn out arrangements and folios.

After a couple of years of recovery, Lampe was found in the 1920 enumeration lodging with Joseph Dell and his wife and in-laws, Frederick Phillips and family. Later in the year he remarried to Millicent E. Krachehl and moved to Queens. In 1921, J.B. was hired by famed bandleader Vincent Lopez to create contemporary arrangements for his Hotel Pennsylvania Orchestra, and to teach him the art as well. Dell also used his father as his primary arranger while the younger Lampe was making the rounds with Lopez and Paul Whiteman, finally landing a long-term run at the Trianon Ballroom on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. While not composing any more, J.B. started arranging for Edward B. Marks in 1922, the last piece with his credit on it showing up shortly after his death in 1929.

A 1922 advertisement cites J.B. as having been the concert master of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra for many years, but how that arrangement worked while he was still working in New York is unclear. He did, however, create specific arrangements for the Lopez group recordings on Edison and O-Keh discs. Reports of J.B. in Chicago for short stays also appeared from 1922 to around 1926. He also founded his own company, the Lampe Music Writing Concern, located at 1595 Broadway, where he spent his final years working. J. Bodewalt Lampe died at home in Queens at age 59 in May 1929. He was laid to rest in nearby Woodlawn Cemetery. Lampe left behind a considerable imprint in both piano and instrumental music that even affected the birth of movie scoring in the late 1920s. Creole Belles remains a favorite into the 21st century for vintage dance bands, traditional jazz bands and ragtime pianists.

Compositions

Compositions