James Sylvester Scott (February 12, 1885 to August 30, 1938) | |

Ragtime Compositions Ragtime Compositions | |

|

1903

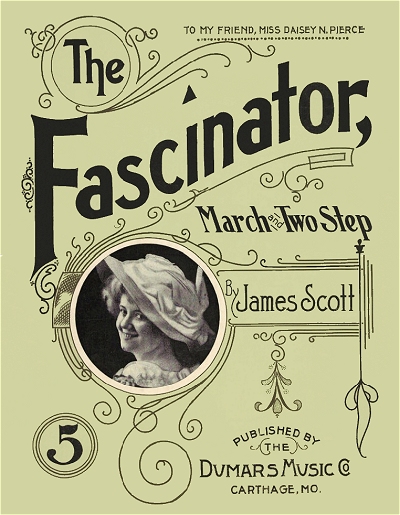

A Summer BreezeThe Fascinator 1904

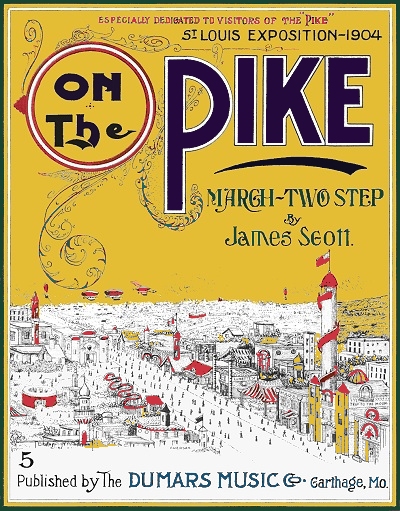

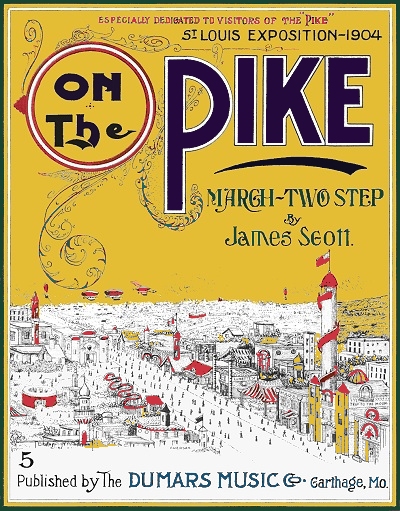

On The Pike1906

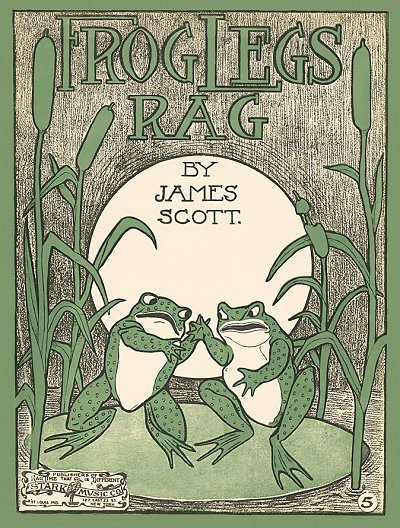

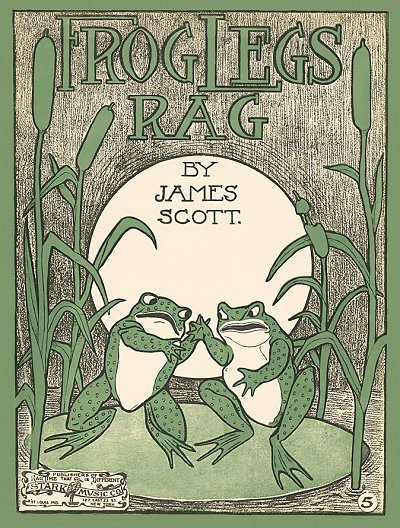

Calliope Rag (c.1906/1964/2001) [1,2]Frog Legs Rag 1907

Kansas City Rag1909

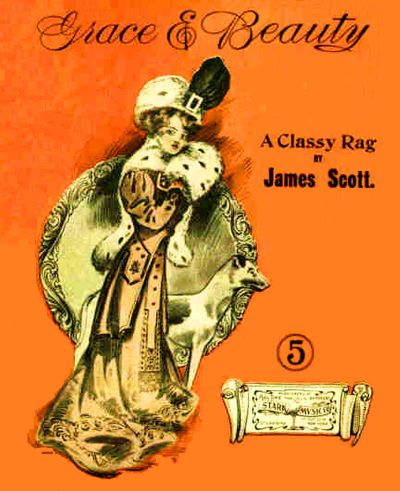

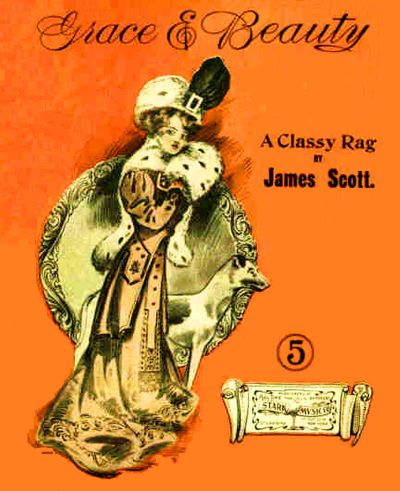

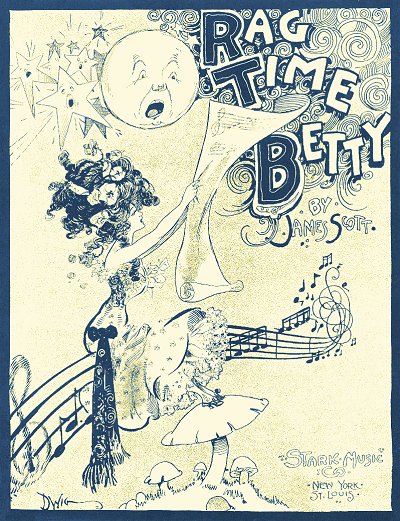

Great Scott RagThe Ragtime Betty Grace and Beauty Sunburst Rag 1910

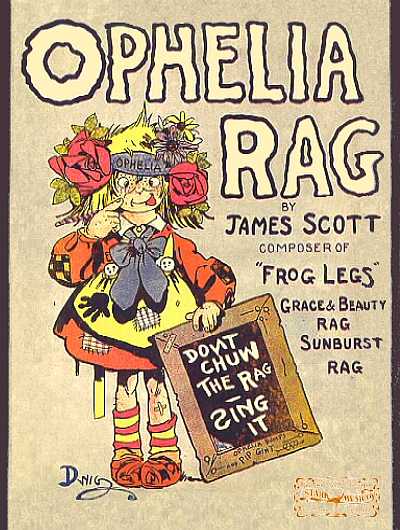

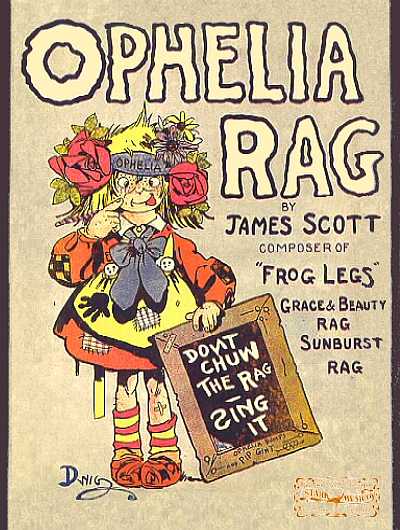

Ophelia RagHilarity Rag 1911

Quality RagRagtime Oriole Princess Rag 1914

Climax Rag1915

Evergreen Rag |

1916

Prosperity RagHoney Moon Rag 1917

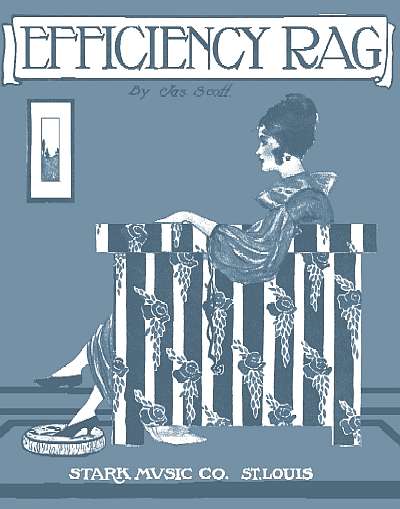

Efficiency RagParamount Rag 1918

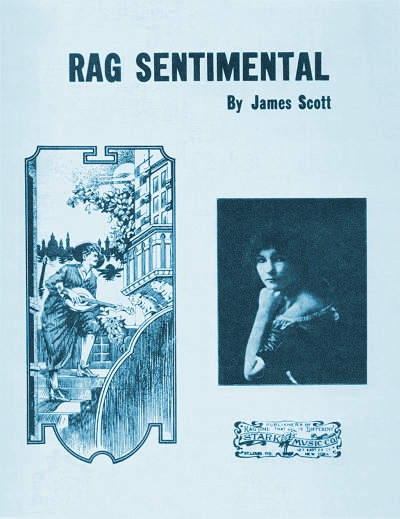

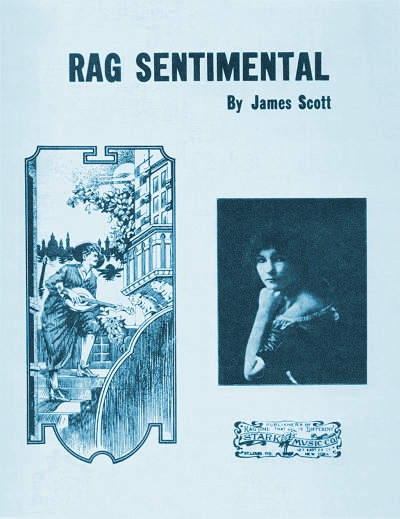

Rag SentimentalDixie Dimples 1919

Troubadour RagNew Era Rag Peace And Plenty Rag 1920

Modesty RagPegasus 1921

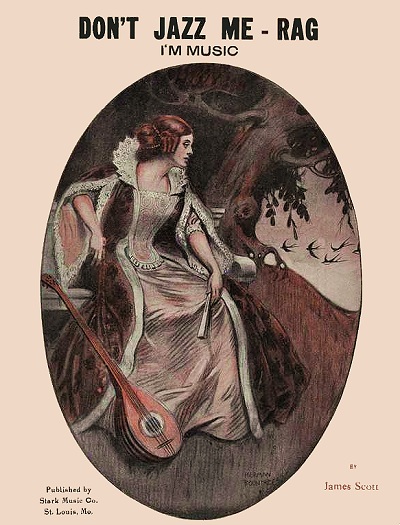

Don't Jazz Me RagVictory Rag 1922

Broadway Rag

1. Enhanced and completed by Bob Darch

2. Rearranged as a piano rag by Bill Edwards |

Songs and Waltzes Songs and Waltzes | |

|

1909

Valse VeniceShe's My Girl from Anaconda [3] Sweetheart Time [3] 1910

Heart's Longing: Waltz1914

Suffragette WaltzTake Me Out to Lakeside [4] |

1918

Springtime of Love: Waltz1920

The Shimmie Shake [5]

3. w/Charles R. Dumars

4. w/Ida Miller 5. w/Cleota Wilson |

James Sylvester Scott (Jr.) was the only major ragtime composer to grow up in southwestern Missouri, primarily in the Carthage area. Born in Neosho, Missouri, about halfway between Joplin and Carthage, he was one of seven children of former slave James Scott from North Carolina and his younger wife Mollie (Thomas) Scott from Texas. While the younger James listed his birth year as 1884 in later years, including on his 1918 draft record, 1885 is more consistent with earlier records, including the 1900 Census in which year of birth was specifically listed rather than implied. His siblings included Lena (1879), Douglass (8/1890), Bessie (1/1895), Howard (1900) and Oliver (1903).

James showed strong musical talent at an early age. His first musical exposure was from his untrained mother, but soon James received some early training in theory and sight-reading from a respected Neosho pianist, as well as private lessons in his teens with a black Carthage music teacher and saloon pianist, John Coleman. Perfect pitch and an innate sense of harmony helped speed along his comprehension and training, and some of his skills were likely self-taught through experience. That the family did not own a proper piano made things difficult, requiring James to use pianos at school or at the houses of neighbors.

For a brief period of a year or so around 1899 the family moved to Ottawa, Kansas, around 150 miles from Neosho. When his family moved back to Neosho around 1901, the only instrument young James had to practice on there was a reed organ which was an inexpensive substitute for an upright. After a few months James Sr. finally procured a used upright piano for the household. Most of the Scott children also showed similar musical talent, and indeed were taught rudimentary keyboard skills by their mother, but did not pursue music as a career. James was the only one that pursued some form of musical literacy, able to both read and notate musical scores. The Scott family was shown living once again in Neosho in June 1900. James was listed as a day laborer at age 15. Scott would move out on his own around 1902 to Carthage, the Jasper County seat, a few miles to the east, while the rest of the family remained in Neosho or a few years.

When his family moved back to Neosho around 1901, the only instrument young James had to practice on there was a reed organ which was an inexpensive substitute for an upright. After a few months James Sr. finally procured a used upright piano for the household. Most of the Scott children also showed similar musical talent, and indeed were taught rudimentary keyboard skills by their mother, but did not pursue music as a career. James was the only one that pursued some form of musical literacy, able to both read and notate musical scores. The Scott family was shown living once again in Neosho in June 1900. James was listed as a day laborer at age 15. Scott would move out on his own around 1902 to Carthage, the Jasper County seat, a few miles to the east, while the rest of the family remained in Neosho or a few years.

When his family moved back to Neosho around 1901, the only instrument young James had to practice on there was a reed organ which was an inexpensive substitute for an upright. After a few months James Sr. finally procured a used upright piano for the household. Most of the Scott children also showed similar musical talent, and indeed were taught rudimentary keyboard skills by their mother, but did not pursue music as a career. James was the only one that pursued some form of musical literacy, able to both read and notate musical scores. The Scott family was shown living once again in Neosho in June 1900. James was listed as a day laborer at age 15. Scott would move out on his own around 1902 to Carthage, the Jasper County seat, a few miles to the east, while the rest of the family remained in Neosho or a few years.

When his family moved back to Neosho around 1901, the only instrument young James had to practice on there was a reed organ which was an inexpensive substitute for an upright. After a few months James Sr. finally procured a used upright piano for the household. Most of the Scott children also showed similar musical talent, and indeed were taught rudimentary keyboard skills by their mother, but did not pursue music as a career. James was the only one that pursued some form of musical literacy, able to both read and notate musical scores. The Scott family was shown living once again in Neosho in June 1900. James was listed as a day laborer at age 15. Scott would move out on his own around 1902 to Carthage, the Jasper County seat, a few miles to the east, while the rest of the family remained in Neosho or a few years.Scott's initial employment was as a bootblack for a black Carthage barber. At age 17, he obtained one of his first performance gigs at Lakeside Amusement Park, a trolley park in Webb City about halfway between Carthage and Joplin, playing both piano and calliope, and sometimes sitting in on sets performed by other area bands. By 1904 he was working for Dumars Music Store owned by local alderman Charles Dumars in Carthage, doing general cleaning work and picture framing. He had also been the director of the Carthage Light Guard Band for nearly two decades. Mr. Dumars quickly discovered Scott's musical abilities and allowed him to demonstrate pianos and popular tunes, the advent of which brought into the store many curious customers resulting in increased sheet music sales. At times the pair also made road trips into the field to sell pianos with James making each instruments sound its best. The store further provided a storage room full of pianos where the youth could practice and even composer in privacy. Dumars eventually helped publish some of Scott's own compositions as well as those co-written with others.

The store further provided a storage room full of pianos where the youth could practice and even composer in privacy. Dumars eventually helped publish some of Scott's own compositions as well as those co-written with others.

The store further provided a storage room full of pianos where the youth could practice and even composer in privacy. Dumars eventually helped publish some of Scott's own compositions as well as those co-written with others.

The store further provided a storage room full of pianos where the youth could practice and even composer in privacy. Dumars eventually helped publish some of Scott's own compositions as well as those co-written with others.It is notable that Carthage, unlike many local towns, had very few drinking establishments or other forms of adult entertainment. Joplin, some 20 miles west, was widely known as a haven for such errant behavior, and was burgeoning with such venues. As James was living in Carthage, however, he did not have to play in saloons or brothels to make a living unlike many other musicians of the time. During this time James composed some songs and his first three piano rags. The first was A Summer Breeze (initially the more esoteric A Summer Zephyr) published by Dumars in 1903. It was well reviewed locally and as far off as St. Louis. Dumars also paid Scott a royalty on each copy, an unusual arrangement for a black composer at the time which Scott Joplin had also received from publisher John Stark for his early pieces. This piece was soon followed by a march called The Fascinator.

In 1904, Dumars published Scott's ragtime tribute to the Lewis and Clark Exposition in St. Louis, On the Pike. It is hard to verify whether the composer, now 19, had actually attended the fabled fair, which is plausible given a train ride of a few hours. However, there is no question that he, and virtually every march or rag or song composer in the country knew of the event which had been delayed for a year due to the enormous electrical infrastructure that had to be set up. The piece sold well in his area, and was also offered for sale at or near the fairgrounds. It was also performed by the Light Guard Band in Carthage in front of the court house on July 11, 1904.

A fine opportunity presented itself in the summer of 1904 when Scott was asked to participate in a concert with John W. "Blind" Boone, noted black pianist who although he was blind from birth could play virtually anything he heard, and brilliantly at that. According to the Carthage Evening Press of August 15, 1904: "...A handful of people which grew to a throng as the entertainment continued occupied the Dumars music store Saturday morning when Blind Boone, Jimmie Scott, and Sousa's band were the attractions. Boone chanced to call at the Dumars store to see his professional friend Jimmie Scott, the young colored man who enjoys a reputation as both composer and piano player. Mr. Scott played for Mr. Boone and in the course of his program did a new and certainly original stunt. A grammaphone [sic] containing a Sousa band piece was turned on and Jimmie played a clever piano accompaniment which really made good music. Boone was delighted and before the selection ended said that he had to get his own hand in. He went to the piano and placing his hand on the treble made his nimble fingers fly over the keys in such a manner as to produce an accompaniment to the whole business which sounded like a piccolo. It seemed as if a whole orchestra was there and the audience was bewildered." Boone took an instant liking to the youth which only helped Scott's reputation grow. The same paper had also labeled Scott as "Our local Mozart," referring to both his performance and compositional skills.

According to the Carthage Evening Press of August 15, 1904: "...A handful of people which grew to a throng as the entertainment continued occupied the Dumars music store Saturday morning when Blind Boone, Jimmie Scott, and Sousa's band were the attractions. Boone chanced to call at the Dumars store to see his professional friend Jimmie Scott, the young colored man who enjoys a reputation as both composer and piano player. Mr. Scott played for Mr. Boone and in the course of his program did a new and certainly original stunt. A grammaphone [sic] containing a Sousa band piece was turned on and Jimmie played a clever piano accompaniment which really made good music. Boone was delighted and before the selection ended said that he had to get his own hand in. He went to the piano and placing his hand on the treble made his nimble fingers fly over the keys in such a manner as to produce an accompaniment to the whole business which sounded like a piccolo. It seemed as if a whole orchestra was there and the audience was bewildered." Boone took an instant liking to the youth which only helped Scott's reputation grow. The same paper had also labeled Scott as "Our local Mozart," referring to both his performance and compositional skills.

According to the Carthage Evening Press of August 15, 1904: "...A handful of people which grew to a throng as the entertainment continued occupied the Dumars music store Saturday morning when Blind Boone, Jimmie Scott, and Sousa's band were the attractions. Boone chanced to call at the Dumars store to see his professional friend Jimmie Scott, the young colored man who enjoys a reputation as both composer and piano player. Mr. Scott played for Mr. Boone and in the course of his program did a new and certainly original stunt. A grammaphone [sic] containing a Sousa band piece was turned on and Jimmie played a clever piano accompaniment which really made good music. Boone was delighted and before the selection ended said that he had to get his own hand in. He went to the piano and placing his hand on the treble made his nimble fingers fly over the keys in such a manner as to produce an accompaniment to the whole business which sounded like a piccolo. It seemed as if a whole orchestra was there and the audience was bewildered." Boone took an instant liking to the youth which only helped Scott's reputation grow. The same paper had also labeled Scott as "Our local Mozart," referring to both his performance and compositional skills.

According to the Carthage Evening Press of August 15, 1904: "...A handful of people which grew to a throng as the entertainment continued occupied the Dumars music store Saturday morning when Blind Boone, Jimmie Scott, and Sousa's band were the attractions. Boone chanced to call at the Dumars store to see his professional friend Jimmie Scott, the young colored man who enjoys a reputation as both composer and piano player. Mr. Scott played for Mr. Boone and in the course of his program did a new and certainly original stunt. A grammaphone [sic] containing a Sousa band piece was turned on and Jimmie played a clever piano accompaniment which really made good music. Boone was delighted and before the selection ended said that he had to get his own hand in. He went to the piano and placing his hand on the treble made his nimble fingers fly over the keys in such a manner as to produce an accompaniment to the whole business which sounded like a piccolo. It seemed as if a whole orchestra was there and the audience was bewildered." Boone took an instant liking to the youth which only helped Scott's reputation grow. The same paper had also labeled Scott as "Our local Mozart," referring to both his performance and compositional skills.James continued to be a popular attraction in the Carthage area and at the growing Lakeside Park. The park itself was racially segregated by Missouri law, but there were special days that black could attend, and black performers were always admitted for work. This brings into partial question one of his compositions from the time frame of approximately 1905 to 1906, the Calliope Rag. The calliope is an instrument that while seemingly simple requires some skill to master a method that exploits the fullest possible range of sound from the instrument. The number of keys varied from 30 to 48, a paltry range for a pianist. They were also exceedingly loud due to their nature, hot steam blowing through metal pipes of varying lengths, intended to lure in customers from far and wide. How often James played this cacophonic instrument is unclear, but there are mentions of him performing on it from time to time. He also played for movies that were shown in the park's theater. He reportedly played there into the mid-1910s.

How often James played this cacophonic instrument is unclear, but there are mentions of him performing on it from time to time. He also played for movies that were shown in the park's theater. He reportedly played there into the mid-1910s.

How often James played this cacophonic instrument is unclear, but there are mentions of him performing on it from time to time. He also played for movies that were shown in the park's theater. He reportedly played there into the mid-1910s.

How often James played this cacophonic instrument is unclear, but there are mentions of him performing on it from time to time. He also played for movies that were shown in the park's theater. He reportedly played there into the mid-1910s.So it was no big surprise to performer Bob Darch when on a visit to the home of some Scott relatives in the Carthage area in the mid-1950s he had to opportunity to view and hand copy (Xerox technology was still not of sufficient quality) some Scott manuscripts. It is likely that the word Calliope was on the sheet, and given the simplicity and the limited scope of the piece it could very well have been composed for the instrument. But as was discovered in interviews with Darch from 1999 to 2001, apparently only the first section was copied, and maybe a partial second section, the rag having been completed by Darch with a little assistance. In 2001, this author reworked the ideas of Darch and Scott, attempting to emulate a piano rag version that encompasses more of the James Scott scope with call and response patterns and other attributes of his, including expanding Darch's 8 measure sections into a full 16 measures. Even at that, there is some controversy that still exists as to whether the first printed version, which first appeared in They All Played Ragtime in 1964, is an authentic James Scott piece. The opinion of the author, which may bear some bias of course, is that it is as much a Scott piece as Heliotrope Bouquet and Kismet Rag are Scott Joplin compositions - which means they are collaborative efforts that bear the mark of each of the named composers.

In 1906 James finally met Scott Joplin in St. Louis. Impressed by both his playing and his compositions, Joplin helped to arrange for the publication of his Frog Legs Rag with John Stark. Whether or not Scott and Stark ever met is unclear, since Stark was in New York City at that time and would be there until 1910.  Joplin may have also had some ancillary affect on James since the complexity and variety of his compositions soon expanded. Frog Legs Rag was enough of a success, second only to Maple Leaf Rag in the catalog, that Stark published virtually anything that Scott sent to him over most of the next twelve to fifteen years. It seems that Joplin and Scott met only once or twice, and did not have any evident ongoing relationship once Joplin moved to New York City around 1907.

Joplin may have also had some ancillary affect on James since the complexity and variety of his compositions soon expanded. Frog Legs Rag was enough of a success, second only to Maple Leaf Rag in the catalog, that Stark published virtually anything that Scott sent to him over most of the next twelve to fifteen years. It seems that Joplin and Scott met only once or twice, and did not have any evident ongoing relationship once Joplin moved to New York City around 1907.

Joplin may have also had some ancillary affect on James since the complexity and variety of his compositions soon expanded. Frog Legs Rag was enough of a success, second only to Maple Leaf Rag in the catalog, that Stark published virtually anything that Scott sent to him over most of the next twelve to fifteen years. It seems that Joplin and Scott met only once or twice, and did not have any evident ongoing relationship once Joplin moved to New York City around 1907.

Joplin may have also had some ancillary affect on James since the complexity and variety of his compositions soon expanded. Frog Legs Rag was enough of a success, second only to Maple Leaf Rag in the catalog, that Stark published virtually anything that Scott sent to him over most of the next twelve to fifteen years. It seems that Joplin and Scott met only once or twice, and did not have any evident ongoing relationship once Joplin moved to New York City around 1907.James formed the Carthage Jubilee Singers which performed local concerts, and he played for the movies at the Delphus Theater in Carthage. He also played with and was exposed to a variety of other musical experiences through Dumar's own Light Guard Band. It is unclear if he went on any of the regional trips that the band took, in part to promote Carthage as a great place to live, as black performers usually did not work with a white band, either due to tradition or to local laws. However through Dumars he undoubtedly heard and was heard by some of the finest talent on the Methodist Chautauqua circuits and visiting vaudeville troupes. There is a chance that during this period he may also have been acquainted with fellow Carthage white composer Clarence Woods, as they had taken from the same piano teacher, and Woods also played for movies and local concerts until he moved to Texas for a while in the mid-1910s.

It was in 1906, with the income from his Dumars job and his rags, that James bought a house in Carthage. He then married Miss Nora Johnson (sometimes listed as Norah). The couple remained married throughout their lives together, but never had children. While still living in southwest Missouri, James had some family ties in the Kansas City area, and likely visited there on occasion. His Kansas City Rag of 1907 was dedicated to a Mr. and Mrs. Matt Penn of Kansas City. During the time John Stark was based New York City, Scott continued to submit consistently fine pieces to him by mail, most of which were quickly published. Among the finest that received praise in print from the Missouri publisher were Grace and Beauty, Hilarity Rag, and Great Scott Rag. He even submitted a waltz that Stark published in 1910, Heart's Longing.

His Kansas City Rag of 1907 was dedicated to a Mr. and Mrs. Matt Penn of Kansas City. During the time John Stark was based New York City, Scott continued to submit consistently fine pieces to him by mail, most of which were quickly published. Among the finest that received praise in print from the Missouri publisher were Grace and Beauty, Hilarity Rag, and Great Scott Rag. He even submitted a waltz that Stark published in 1910, Heart's Longing.

His Kansas City Rag of 1907 was dedicated to a Mr. and Mrs. Matt Penn of Kansas City. During the time John Stark was based New York City, Scott continued to submit consistently fine pieces to him by mail, most of which were quickly published. Among the finest that received praise in print from the Missouri publisher were Grace and Beauty, Hilarity Rag, and Great Scott Rag. He even submitted a waltz that Stark published in 1910, Heart's Longing.

His Kansas City Rag of 1907 was dedicated to a Mr. and Mrs. Matt Penn of Kansas City. During the time John Stark was based New York City, Scott continued to submit consistently fine pieces to him by mail, most of which were quickly published. Among the finest that received praise in print from the Missouri publisher were Grace and Beauty, Hilarity Rag, and Great Scott Rag. He even submitted a waltz that Stark published in 1910, Heart's Longing.Two unusual entries garnered some innovative and exclusive sheet music cover art. The first was The Ragtime Betty in 1909, followed by Ophelia Rag named for the popular comic strip character Ophelia Bumps drawn by Clare Victor Dwiggins. Dwiggins' only relation to Missouri was that his wife was born there. He was in Manhattan around that time, so it is likely that John Stark approached him about drawing the cover, to which Dwiggins complied. These were the only two music covers known to have been drawn by this artist, but Ophelia clearly benefitted from his colorful artwork. Two other pieces from 1909 were collaborations with his overall mentor and biggest supporter, Charles Dumars. One was the rather busy Girl from Anaconda to which Scott did the best job he could with the mouthful of words Dumars had given him. The other, Sweetheart Time, a pleasant waltz song typical of the era.

Before 1908 James Sr. and Mollie have moved to Carthage with four of their children. Mollie Scott died at home on October 3, 1908, the cause listed as "Heart Disease." James remarried in late 1909 to Ella Lesper of Missouri. Scott was shown living at 707 East Sixth Street in Carthage in 1910, listed as a musician and piano salesman. It is notable that this was one of the better areas of town, and the street was occupied by several white, black and mulatto residents, James and Nora listed as the latter. His father, stepmother, and four of James' younger siblings were living nearby at 819 E. Fifth Street, also a well-integrated neighborhood.

James and Nora listed as the latter. His father, stepmother, and four of James' younger siblings were living nearby at 819 E. Fifth Street, also a well-integrated neighborhood.

James and Nora listed as the latter. His father, stepmother, and four of James' younger siblings were living nearby at 819 E. Fifth Street, also a well-integrated neighborhood.

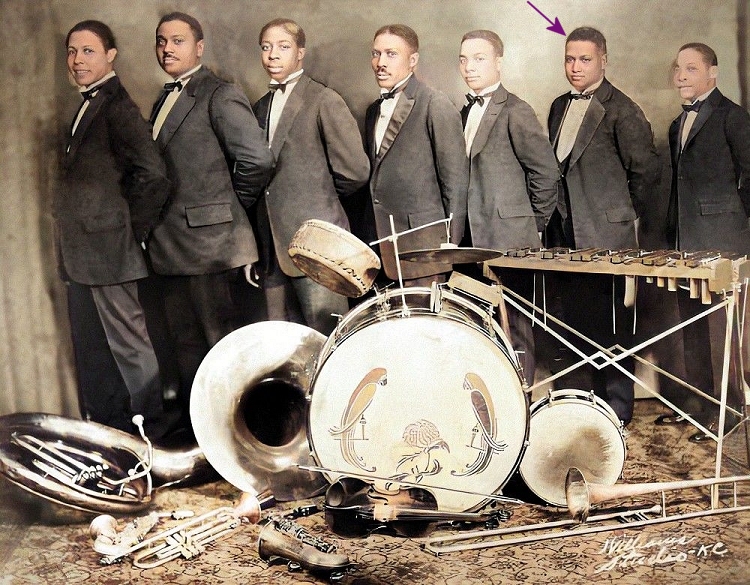

James and Nora listed as the latter. His father, stepmother, and four of James' younger siblings were living nearby at 819 E. Fifth Street, also a well-integrated neighborhood.Jimmie had other ambitions in addition to his playing and composing. Noting that bands were segregated, and that the area lacked a Negro equivalent to the Light Guard band, he worked hard to form and maintain his own band with black musicians recruited from as far off as Joplin. There were notices in the Carthage Evening Press of performances not only at Carter Park but at the local African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, and social events at the Carthage Armory. As with many groups of this size, including the fabled bands of James Reese Europe and Fred S. Stone, Jimmie had some smaller ensembles available for hire from the group as well, making it easier to mine for work in a slagging economy.

Scott continued to work for Dumars until 1914 before turning to performing and teaching full time in southwest Missouri. He had also continued to send at least one to two new rags per year to Stark for publication, perhaps more that went unpublished until later. Two standouts were published in 1911. Ragtime Oriole managed to include emulations of the bird from the title, and Quality Rag further lived up to its name. Both are heavy with hallmarks of Scott's style, including call and response patterns that harken back to the days of slavery and ring shouts, and compact but efficient two measure phrasing. He may have been submitting rags in 1912 and 1913, but the next one to be published was in 1914. Climax Rag was another complex example of Jimmie's evolving style, and may be one of the closest to capturing his dynamic playing style in print. To compliment this rag Stark also published the topical Suffragette Waltz around the same time. Also in 1914 he wrote the music for Take Me Out to the Lakeside in honor of the Webb City park, to words by Ida Miller, the wife of a local entrepreneur who owned tourist cabins in the area. It was an attempt to capture the Meet Me in St. Louis type of song of the past decade, but did not see much circulation outside of Missouri, having been published in Carthage.

Also in 1914 he wrote the music for Take Me Out to the Lakeside in honor of the Webb City park, to words by Ida Miller, the wife of a local entrepreneur who owned tourist cabins in the area. It was an attempt to capture the Meet Me in St. Louis type of song of the past decade, but did not see much circulation outside of Missouri, having been published in Carthage.

Also in 1914 he wrote the music for Take Me Out to the Lakeside in honor of the Webb City park, to words by Ida Miller, the wife of a local entrepreneur who owned tourist cabins in the area. It was an attempt to capture the Meet Me in St. Louis type of song of the past decade, but did not see much circulation outside of Missouri, having been published in Carthage.

Also in 1914 he wrote the music for Take Me Out to the Lakeside in honor of the Webb City park, to words by Ida Miller, the wife of a local entrepreneur who owned tourist cabins in the area. It was an attempt to capture the Meet Me in St. Louis type of song of the past decade, but did not see much circulation outside of Missouri, having been published in Carthage.As the pending war and the United States' involvement in it approached, the economy in the area started to suffer, in part because the zinc mining industry which had been a staple there was slowing down due to depletion. Other than agriculture, Carthage Marble became the biggest industry, but leisure activity often had to be put aside, creating less work for people in the music and entertainment fields. One last event was noted for his band, which played at the Armory while sending black draftees from Jasper County off to the army in 1917.

At some point between in mid to late 1917 James and Nora moved to Kansas City, Kansas, where he would spend the rest of his life. Evidence suggests that it took a while or Scott to build up both clientele and playing jobs. On his September, 1918 draft record, where he uses the name Jim Scott, he is listed as an elevator operator for the F.T. Altman firm in Kansas City, Missouri, while he and Nora were living at 352 Rowland Avenue on the Kansas side of the border. Even when he started performing, most of his work was actually on the Missouri side of Kansas City. In 1920 he is finally listed as a theater musician, and Nora as an entertainment cateress, with the couple living at 2404 North Fifth Street, still on the Kansas side.

In 1917 his brilliant Efficiency Rag was published by Stark, along with Paramount Rag The following year Stark brought out Rag Sentimental, which in some ways broke the Scott ragtime mold with a more contemplative piece. Dixie Dimples, on the other hand, was the only late rag not published by Stark, instead coming out under the label of Will Livernash in Kansas City, Missouri. Three more Stark issues came in 1919, including Troubadour Rag, the topical Peace and Plenty rag, and his keyboard encompassing New Era Rag.

Dixie Dimples, on the other hand, was the only late rag not published by Stark, instead coming out under the label of Will Livernash in Kansas City, Missouri. Three more Stark issues came in 1919, including Troubadour Rag, the topical Peace and Plenty rag, and his keyboard encompassing New Era Rag.

Dixie Dimples, on the other hand, was the only late rag not published by Stark, instead coming out under the label of Will Livernash in Kansas City, Missouri. Three more Stark issues came in 1919, including Troubadour Rag, the topical Peace and Plenty rag, and his keyboard encompassing New Era Rag.

Dixie Dimples, on the other hand, was the only late rag not published by Stark, instead coming out under the label of Will Livernash in Kansas City, Missouri. Three more Stark issues came in 1919, including Troubadour Rag, the topical Peace and Plenty rag, and his keyboard encompassing New Era Rag.From 1919 on there is some question as to whether James' rags were being issued in a timely manner by Stark, as some pieces were sounding similar to 1915 and 1916 issues, and Scott was performing more jazz music now by necessity. Stark had shown a pattern of hanging on to submitted works until it suited him to issue them, which makes it hard to determine the order of when the last rags were submitted and when they were composed. In some cases, however, the freshness of the piece was evident, as with the magnificent Pegasus from 1920, and the only Stark issued song by James, The Shimmie Shake, which contained lyrics of a current popular dance written by Cleota Wilson.

Scott taught piano in a studio he set up near his home, and soon purchased a grand piano, which he later said was his most prized possession. He played in some of the movie houses for a time as a soloist, in particular at a long-term position at the Panama Theater. Vaudeville provided a fairly certain haven for performers like Scott, particularly for black audiences thirsty for their own brand of music, and he took good advantage of this need. He was also a viable commodity as a fill-in accompanist for visiting acts, and playing for the short films commonly shown between some performances. Due to his diminutive height (5'4") and musical vigor, he was became known throughout the area as "The Little Professor."

The increasing complexity of Scott's later rags demonstrate his considerable pianistic skills. His love of the genre was clearly demonstrated in one of his last published rags, Don't Jazz Me, (I'm Music), although that rag, like most of his pieces submitted without titles, was likely named by John Stark or a member of his firm. Stark in particular was frustrated with the onslaught of loose (by the standards of that time period) jazz music, and the title of this ironically somewhat jazzy piece was one of his final editorials on the passing of classic ragtime. Stark was doing all he could to counter the onslaught of jazz, issuing Victory Rag and Broadway Rag well after they were submitted by Scott, and they were among the last pieces published by the pioneering classic ragtime supporter. Both also sounded more like the batch of mid-1910s rags which may have been held back until they were deemed viable, or even necessary by the publisher.

In 1924 James joined the Musicians Union in Kansas City which instantly opened up new venues for him. One of these was the Lincoln Theatre which featured a seven piece band led by Harry Dillard, and had its own stable of vaudeville performers.

The band became a twenty piece orchestra within the next two years, playing for the house acts, visiting acts, and even the occasional scored movie. They eventually called themselves The Lincoln Symphony Orchestra, boasting a repertoire that included some fine classical works. Scott's accumulative skills in both composing and arranging along with his semi-classical background made him a vital part of the organization. Jimmie had also formed his own seven piece band to work local venues. He wrote most of the arrangements, and the group sometimes accompanying local blues singer Ada Brown, a cousin of his.

|

Jimmie moved on to a steady playing job at the black-owned Eblon Theater in the busy theater district of 18th and Vine Street in Kansas City, Missouri, with his band. After a good run from late 1926 to late 1928, the band was sidelined by economic troubles and dropping attendance. However, James was able to retain his position even after his band was replaced by a $15,000 Wicks theater organ, as he turned out to be quite capable at that instrument as well. Another musician that played that same organ was Kansas City's own William "Count" Basie, nearly 20 years younger than James, who would sneak in at times just to improve his own skills on the massive instrument.

In 1930 Scott's wife Nora died at age 46, as did a continuing career playing for the movies due to the advent of synchronized sound films. After working through his multiple losses, Jimmie regrouped and formed another band, eight pieces this time. They played for special engagements whenever they could find work during the Great Depression. Towards the end of his life James was in continuously poor health, but kept composing, and moving, reportedly living in four residences, sill on the Kansas side of the border, between 1931 and 1938. His last move was in 1936 to the home of his cousin, Ruth Callahan. Until 1936 his primary income was from teaching piano. He finally succumbed to kidney failure and arteriosclerosis in 1938 at age 53. All of his final works remain unpublished and even undiscovered. To the best of our knowledge he also left behind no piano roll performances (highly unlikely since Chicago and New York where were most of them were done) or recordings.

James had been buried next to Nora at Westlawn Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas, but for many years their gravesite remained unmarked. Ragtime performer and promoter Bob Darch told of his efforts to find Scott's burial place in the 1950s, which included a mild alcoholic bribe to the groundskeeper, only to find the cemetery overgrown, the Scotts' location poorly marked, and overall sad conditions as it was also a dumping ground. Since then many Kansas City rag enthusiasts, led by by Smiley and Helen Wallace, made an effort to honor their adopted composer with a new headstone, which was dedicated at a ceremony on May 3, 1981. The site is now well kept and often visited by ragtime fans. The inscribed epitaph on James Scott's headstone reads "The Grace and Beauty of His Music Will Live Always." Fortunately ragtime did not die with him, and the vivacity of James Scott pieces will long be enjoyed by new generations of rag enthusiasts.

It should be noted that the author's family was long based in Carthage, Missouri, and his grandfather Paul Scroggs had some memory of hearing ragtime played there in his youth. Some of the research on Scott was done on site from the mid-1980s through 2005 during family visits to Carthage and Jasper Missouri as well as the Kansas City area. The rest was researched in public records and periodicals.