|

Frank Henri Klickmann (February 4, 1885 to June 25, 1966) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1906

Oh! Babe!1910

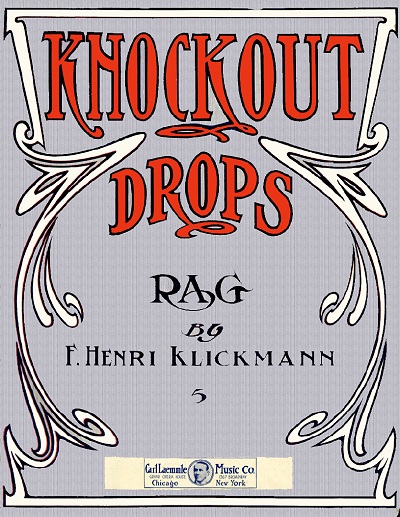

Knockout Drops: A Trombone Jag1911

I Will Love You When the Silver Threads AreShining Among the Gold Uncle Sam Rocking Waves: Reverie Jesse James [1] 1912

Gleam of SunshineHappy Cy Garden of Allah - Waltzes Rose Leaves Delirium Tremens Rag: A Trombone Spasm The Parcel Post: March Since I Met You Sweet Dreams The Ragtime Band in Harmony Hall [1] Every Fellow Has a Girl but Me [1] In the Far Off Golden West [1] Saturday Night [1] My Sweetheart Went Down with the Ship [2] Just a Dream of You Dear [w/Charles F. McNamara] 1913

Hesitation WaltzWoolworth Rag Sabbath Chimes: Reverie Tango Argentino True Love - Syncopated Waltz Meet Me in the Twilight [2] When the Turkey in the Straw Danced the Chicken Reel [2] It Doesn't Matter Though Your Hair is Gray [2] Sing Me the Rosary (The Sweetest Song of All) [2] Sing to Me, Mother, Sing Me to Sleep [2] Dynamite - A Noisy Rag (aka Trombone Troubles) [3] The Squirrel Rag [3] 'Round the Hall [3] 1914

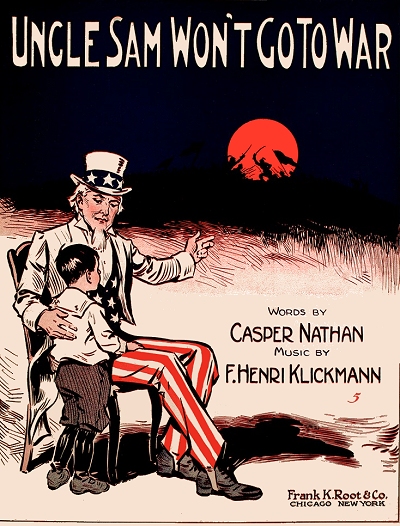

Peach Blosomm WaltzThe Brazilian Maxixe Sunday Morning Chimes Half and Half The Original Fox Trot I'm Off for Mexico (Patriotic Song) Sparkling Dewdrop Dream Waltz (Barcarolle adapted from Tales of Hoffman) Diane Of The Green Van [2] There's a Mother Back in Ireland Waits for Me [2] Mama Can't Pray For Us Now [2] Aunt Jemima's Picnic Day [2] Our Flag to the Sea [2] I Long to Hear the Old Church Choir Again [2] When You Sang "The Palms" For Me [2] I Want to Kiss Mama Good-Night [2] What Would You Take for the Baby? [2] The Murray Walk [3] Irresitible: Valse [3] Mindanao - A Moro Dance [3] Hysterics Rag: A Trombone Fit [3] Uncle Sam Won't Go to War [4] Little Lost Sister [4,12] Say I Died for My Country's Sake [12] 1915

When Love is Silent: Tone PoemThe Boys from Home High Yellow: Cake Walk The World Will Go On Just the Same Tambourines and Oranges No Matter What Flag He Fought Under (He was Some Mother's Boy After All) [2] They All Sang Annie Laurie [2] There's A Rose in Old Erin [2,3] The Kiss That Made You Mine [2,3] Harriman: Fox Tango [3] When The Silv'ry Moon Is Shing on the Golden Harvest Sheaves [5] As the Lusitania Went Down [5] Roll Along, Harvest Moon [w/R.G. Gradi] I'm Going to Meet My Sweetheart [w/Della Rodefer] Dream Face [w/Lola B. Allison] Annabelle (There's a Lovin' Comin' to You [w/George A. Little] 1916

Bow-Wow!Star of Paradise Dodo [3] Oh! Those Blues! (Lazy Blues, Crazy Blues! [3] [w/Isadore Murphy] My Phantom Girl [3,6] My Honey Lu [3,6] Theda Bara: I'll Keep Away From You [6] 1917

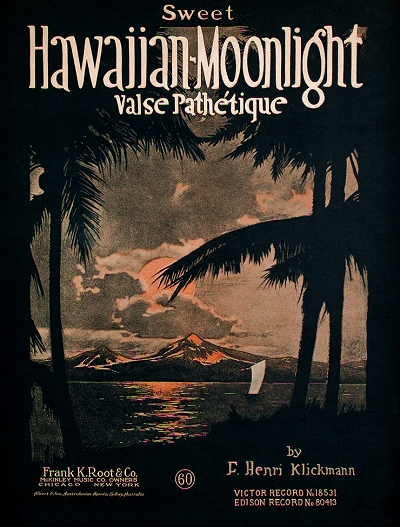

Smiles and Chuckles RagGhost of Mr. Jazz Hawaiian Moonlight - Valse Ghost Of The Saxophone Back To Mother and Home Sweet Home [2,6] Way Down In Macon, Georgia (I'll be Makin' Georgia Mine) [3,6,7] My Fox Trot Girl [3] That Beautiful Baby of Mine [6] My Fox-Trot Girl [3,6] Down at Waikiki [3,6] Saxophone Sam [3,6] Let's Go Back To Dreamy Lotus Land [3,6] Come Back To Bamboo Land (To Your Lonely Little Mi Mio San) [3,7] A Rag-Time Lullaby [6] Good-Bye, Aloha [6] 1918

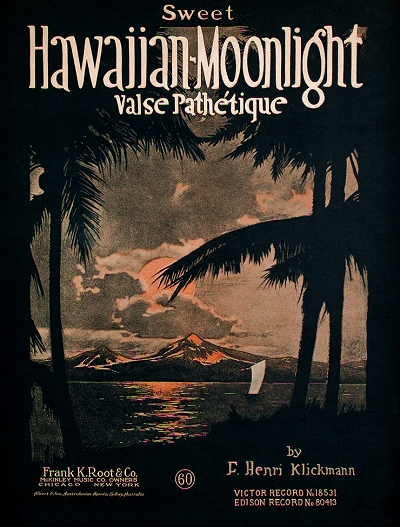

My Uncle Sammy GalsLet's Keep The Glow in Old Glory and the Free In Freedom Too Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight (Valse Pathétique) Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight (Tell Her of My Love) [6] Oh, Babe! - Just Save Your Kisses for Your Yankee Soldier Boy [6] The Trench Trot [6] Soldier Boy, Come Back to Me [8] If A Mother's Prayers are Answered, Then I Know You'll Come Back to Me [8] Old Glory Goes Marching On (The Flag that Never Knew Defeat) [8] |

1918 (Cont.)

It'e For You, Old Glory, It's For You [8]Will The Angels Guard My Daddy Over There? [8] Keep Your Face to the Sunshine [8] Let the Chimes of Normandy Be Our Wedding Bells [8] There's a Little Blue Star in the Window (And it Means All the World to Me) [8] When the Little Blue Star in the Window Has Turned to Gold [8] Souvenir (Violin/Piano) [w/Franz Drdla] 1919

I Wouldn't Do It For Anyone But YouFloatin' Down to Cotton Town [6] Pickaninny Blues [6] Oasis [6] My Rose of Mandalay [6] Rainbow Land [6] Weeping Willow Lane [6] Under Southern Stars [6] Wishing Moon [6] I Wonder What's Ze Matter Wiz My Oo-La-La? [6] Hawaiian Rose [8] When I Met You [8] When You Hold Me In Your Arms [9] Dixie Moon [9] 1920

Paderewski RagLazy Jazz Waltz Desertana [3,6] There's Only One Pal After All [3,6] Smoke Rings [6] Pond-Lily Time [6] I've Got the Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight Blues [6] Do You? [6] One Little Girl [6] Shimmy Moon [6] Overalls: Fox Trot Song [6] Sleepy Hollow (Where I First Met You) [6] [w/Lemuel Fowler] 1921

Sighing Just for You [6,11]Italy [10,11] Main Street [11] [w/Vincent M. Sherwood & Hazel Crawford] Alabama Jamboree [11] Moonlight Land [w/Homer Dean] Oh! Henry! (Your Sweet Mamma Misses You) [w/J. Brandon Walsh & Bonnie Benedict] 1922

My Virginia RoseSouthern Rose For Old Time's Sake (Just One More Waltz Before We Part) [10] The Trail To Long Ago [10] I Love You Angel Eyes [10] Hawaii - I'm Dreaming of You [10] Broken-Hearted Blues [w/Roy Bargy & Dave Ringle] In Old California With You [10] Gee! I'd Give the World to Be Back Home Again [10] 1923

I'm Goin' Back To My MammyI Ain't Got Nobody Blues [6] Loving You [10] Till My Dreams Come True [w/Leo Friedman & Beth Slater Whitson] 1924

Eili, Eili (Hebrew Folk Song)[w/George D. Lottman] [4] Souvenir (Song) [4] [w/Franz Drdla] 1925

Star of Love - ReverieWaters of the Perkiomen [4] Bryan Believed in Heaven (That's Why He's in Heaven Tonight) [4] [w/William Raskin] Since You Called Me Sweetheart [w/Milton Weil & Bob White] 1926

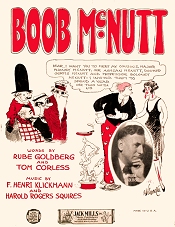

Boob McNutt [w/Harold Squires, RubeGoldberg & Tom Corless] 1927

Lady Moon: Waltz SongSpirit of St. Louis: March 1932

Empire State March1934

Songs of the Roundup (Folio) [13]1935

Roll On, Beautiful Sea, Roll On [15]Hearts Courageous [15] We'll Push Those Clouds Away [w/A.W. Kerr] 1938

I Find in You [w/David Ormont]1944

Mothers of the NationA Speedy Recovery to You [14] [w/Kenny Manges] I'd Like to Send Her Flowers for Easter [14] 1946

Hello, New Year, Hello! [16,17]Stingy [16,17] Something Tells Me [16] [w/M.S. Stoner] Christmas Comes but Once a Year [16,17] Hotcha Potcha Peacha [w/Melvin Rosenblum] Unknown

Walnut Hills MarchGood Morning Waltz Jumpin' Jupiter Polka Jolly School Girls Mud Pies

1. w/Roger Lewis

2. w/J. Will Callahan 3. w/Paul Biese 4. w/Al Dubin 5. w/Arthur J. Lamb 6. w/Jack Frost or Harold G. Frost 7. w/Ernie & Billie Loos 8. w/Paul B. Armstrong 9. w/George Buchanan 10. w/Clinton E. Keithley 11. w/Cal De Voll 12. w/Casper Nathan 13. w/Sterling Sherwin 14. w/Maruice Crance 15. w/Clarke Van Ness 16. w/Andy Razaf 17. w/George A. Haggar |

Frank Henri Klickmann spent much of the early part of his life where he originated, in Chicago, Illinois. Born to a German immigrant Rudolph Klickmann (frequently misspelled as Klickman) and his Illinois native wife Carolina Laufer, he was the second of five children, including Emily (12/1881), Ida (6/1887), Robert (12/1890) and Florence (7/1899). Music was an important part of their family. His older sister Emily was listed as a Music Teacher at age 19, when Frank was still an errand boy at 15, yet he was playing and studying music at that time.

Going beyond his early training in the Chicago public school system, Klickmann studied in Chicago with a variety of talented teachers, including his uncle Ernest Louffer, Louise Harmon, Armin Hirsch, Alfred Piatti and Mrs. Walter Stein. It is not certain when he dropped the Frank in favor of F., but in 1906 his first publication, Oh Babe, appeared under that name, and in the 1910 census, he listed himself as F. Henri Klickmann, composer and arranger. It was also in 1910 that Klickmann's initial rag output started appearing, and soon his pen was influencing many forms of popular music both in the foreground and background. Frank was married to Kentucky native Jeannette Gossett, more than three years his senior, on February 19, 1908. It was his first marriage, but her second. They were found living near downtown Chicago for the 1910 enumeration.

It is not certain when he dropped the Frank in favor of F., but in 1906 his first publication, Oh Babe, appeared under that name, and in the 1910 census, he listed himself as F. Henri Klickmann, composer and arranger. It was also in 1910 that Klickmann's initial rag output started appearing, and soon his pen was influencing many forms of popular music both in the foreground and background. Frank was married to Kentucky native Jeannette Gossett, more than three years his senior, on February 19, 1908. It was his first marriage, but her second. They were found living near downtown Chicago for the 1910 enumeration.

It is not certain when he dropped the Frank in favor of F., but in 1906 his first publication, Oh Babe, appeared under that name, and in the 1910 census, he listed himself as F. Henri Klickmann, composer and arranger. It was also in 1910 that Klickmann's initial rag output started appearing, and soon his pen was influencing many forms of popular music both in the foreground and background. Frank was married to Kentucky native Jeannette Gossett, more than three years his senior, on February 19, 1908. It was his first marriage, but her second. They were found living near downtown Chicago for the 1910 enumeration.

It is not certain when he dropped the Frank in favor of F., but in 1906 his first publication, Oh Babe, appeared under that name, and in the 1910 census, he listed himself as F. Henri Klickmann, composer and arranger. It was also in 1910 that Klickmann's initial rag output started appearing, and soon his pen was influencing many forms of popular music both in the foreground and background. Frank was married to Kentucky native Jeannette Gossett, more than three years his senior, on February 19, 1908. It was his first marriage, but her second. They were found living near downtown Chicago for the 1910 enumeration.There is a good chance that Frank had been playing the trombone in his late teens in addition to piano and violin, as many of his pieces not only show some of the slide influence also put down by composer Arthur Pryor, but actually mention trombone in the subtitle. This includes his first ambitious rag, Knockout Drops, subtitled A Trombone Jag. Starting in 1913, Some of his early rags were co-written with the largely unknown at that time saxophonist and bandleader Paul Biese, including the enjoyable Squirrel Rag and Dynamite Rag, the latter yet another trombone-themed piece. Biese, a fine musician, needed Klickmann to fill in chording and arrangements of his melodies, and they collaborated on several songs and instrumentals over the next four years. It wasn't long before Klickmann found his place as a songwriter as well, including one of the earliest pieces to capitalize on the Titanic tragedy, My Sweetheart Went Down with the Ship. That same year saw another wild piece, Delirium Tremens Rag subtitled A Trombone Spasm. Frank joined up with Biese for a while, arranging for and sometimes performing with his orchestra.

The level of Klickmann's songwriting talent rose throughout the 1910s, and even early on in his career he was in demand as a talented piano and band arranger, employed by both Will Rossiter and Frank Root in Chicago, then for the McKinley Music Company from around 1914 on once McKinley's company. One of his first McKinley song hits, first published by Root, was a topical anti-war song that got notice in the trades:

The McKinley Music Co., of Chicago, Ill., has taken quick advantage of the present international situation by publishing a new song by Caspar Nathan, music by Henri Klickmann, entitled "Uncle Sam Won't Go to War." The new song has made quite an impression on the profession, many prominent singers having made arrangements to use it. The chorus, reproduced herewith, illustrates the real character of the piece:

Uncle Sam won't go to war,

That's not what the U. S. got united for;

Let all Europe fight, if they must,

But the Yankee motto is "In God we trust."

When war clouds roll by once more,

Things will he the same as before;

Our country's always free, No matter what may be -

Uncle Sam won't go to war.

It did not matter that the thrust of the song would prove to be incorrect in two years, as many in the country held that same anti-war stance even as "The Great War" was being won with American help. Klickmann's notable ragtime output in the mid-1910s included his High Yellow Cakewalk during a brief revival of that dance in 1915, and Smiles and Chuckles, a good seller in 1917.

The difficulties of working on the road, or even at home, and continuing to supply material for Biese's orchestra finally overcame Henri. In May 1917 it was announced in the trades that: "F. Henri Klickmann, the composer-arranger, has severed connections with the Paul Biese orchestra in order to devote all of his time to arranging. He is making his headquarters with the McKinley Music Commpany." Henri had already worked for them for many years, but was now able to commit to a more stable contracting situation.

An article in The Music Trade Review of November 30, 1918, outlined an example of how a hit song, this one involving Klickmann, was made, and it was not too far off the mark from a historical perspective of Tin Pan Alley production:

It is decidedly interesting once in a while to discover just how and why a good thing is done. The revealing of the genesis of a good idea is always worth while. Out of the mire and mush of the popular music it is refreshing now and then to find a fine gem like "Keep Your Face to the Sunshine and Behind You the Shadows Will Fall," which issued from the press of the McKinley Music Co. a few months ago. President Wm. McKinley [not the decease POTUS but the coincidental name of the company founder] the other day told its story to The Review, and as the song is meeting with the success it deserves the tale is worth the retelling.

Mr. McKinley is a most careful reader of the music papers, both trade and-professional, and in one of them he found a summary of an address by Macklyn Arbuckle, the well-known actor, in which he dilated upon the duty of cheerfulness and helpfulness on the part of actors and other people in war times and in other times. In the course of it he said: *'I have a motto in life. I have always tried to live up to it. 'Keep your face to the sunshine, and the shadows will fall behind you.' "

"That's good," quoth Mr. McKinley, who is known as somewhat of a sun-spreader himself. The next moment he thought, "That would be a fine idea for a song." Then he called for a conference which was speedily answered by Paul Armstrong, who writes lyrics, Henri Klickman, who writes music, Mr. Sawyer, who arranges, and E. T. Root. This group has been in at the birth of many a good McKinley song. They liked the idea and it kindled the fires of inspiration. The lyric writer first lyricized the title and then got busy on the words of the song. The composer struck a few chords and soon the melody evolved. In a week or two the song went forth on its mission of peppizing sunniness. That's the way things are done down at the McKinley plant.

Frank's 1918 draft record showed McKinely Music as his employer in the capacity of a composer and arranger of music. The Klickmanns were living at 1501 E. 55th Street near downtown.  His big hits of 1918 included Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight in both instrumental and song form, and the topical Let the Chimes of Normandy Be Our Wedding Bells. Some of Frank's arrangements also made it to New York publishers of the time, including the prestigious Waterson, Berlin & Snyder. As of the 1920 census Frank and Jeannette were shown living in downtown Chicago at 1443 Rosemont Avenue, with Frank (as Henri) listed as a composer of music. That year he also wrote a fun variation on his earlier hit, producing I've Got the Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight Blues.

His big hits of 1918 included Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight in both instrumental and song form, and the topical Let the Chimes of Normandy Be Our Wedding Bells. Some of Frank's arrangements also made it to New York publishers of the time, including the prestigious Waterson, Berlin & Snyder. As of the 1920 census Frank and Jeannette were shown living in downtown Chicago at 1443 Rosemont Avenue, with Frank (as Henri) listed as a composer of music. That year he also wrote a fun variation on his earlier hit, producing I've Got the Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight Blues.

His big hits of 1918 included Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight in both instrumental and song form, and the topical Let the Chimes of Normandy Be Our Wedding Bells. Some of Frank's arrangements also made it to New York publishers of the time, including the prestigious Waterson, Berlin & Snyder. As of the 1920 census Frank and Jeannette were shown living in downtown Chicago at 1443 Rosemont Avenue, with Frank (as Henri) listed as a composer of music. That year he also wrote a fun variation on his earlier hit, producing I've Got the Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight Blues.

His big hits of 1918 included Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight in both instrumental and song form, and the topical Let the Chimes of Normandy Be Our Wedding Bells. Some of Frank's arrangements also made it to New York publishers of the time, including the prestigious Waterson, Berlin & Snyder. As of the 1920 census Frank and Jeannette were shown living in downtown Chicago at 1443 Rosemont Avenue, with Frank (as Henri) listed as a composer of music. That year he also wrote a fun variation on his earlier hit, producing I've Got the Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight Blues.One of his more unsung but musically influential arranging jobs was putting many of Zez Confrey's into a more readable form for accompanied instruments for Jack Mills in the early 1920s, in addition to arranging works for other Mills composers. His most frequent lyricist by this time was the prolific Harold G. Frost (1893-1959) more widely known as Jack Frost. They turned out a considerable number of well-crafted tunes in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Among the groups he arranged for frequently were the Six Brown Brothers, for which a number of saxophone-themed songs were composed as well. He also did a lot of work for stage star Eddie Cantor. Some of Frank's more interesting output involved a blending of classical and impressionist music forms with more popular genres. Klickmann also joined ASCAP in 1921, seven years after it was founded.

Sometime between 1922 and 1923 Frank and Jeannette left the Midwest for the more musically lucrative Manhattan where he spent his remaining years. He had already been contracting his services to New York publishers, so the relocation made good sense. One of his more interesting contributions of this era came out right after the Scopes (Monkey) Trial and the death of William Jennings Bryan when he wrote the music for a tune titled Bryan Believe in Heaven (That's Why He's in Heaven Tonight), one of the few topical pieces he was involved in outside of those written during World War One. Klickmann also did a large number of ukulele arrangements for popular music, and some folio work for accordions as well. Waters of the Perkiomen was originally composed for accordion.

In December 1923 Jack Mills hired Klickmann to the staff full time, as noted in The Music Trade Review of January 12: "Jack Mills, Inc., the well-known popular music publishing house... recently announced that it had acquired the exclusive service, for a long term, of F. Henri Klickmann, a particularly well-known music arranger and composer. Mr. Klickmann is a student of the piano and violin, and his arrangements, both as to harmony and composition, show his early studies under some internationally known teachers. His most noteworthy accomplishments have been attained in Chicago, the city of his birth, but his fame, particularly in musical circles, is widely spread throughout the country. Among the well-known orchestral arrangements he has made have been 'The Vamp,' 'Walkin' the Dog,' 'Darktown Strutter's Ball,' 'Kitten on the Keys,' 'Some of These Days,' 'Don't You Remember the Time' and 'Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight.' Mr. Klickmann comes to the rapidly expanding Mills organization well equipped to supervise an arranging department that has already won an important place in the music publishing field."

Jack Mills saw the benefit of not only publishing song folios and instruction books, but focusing on non-piano instruments as well. As the ukulele craze was reaching a zenith in 1924, Frank edited a book of popular pieces by Victor recording star and ukulele player Wendell Hall,  with a little assistance from another busy uke arranger, May Singhi Breen. One of the earliest books on Jazz performance was written by Klickmann in 1926 and published by Mills. He also had a hand in many of the novelty numbers put out by the firm, as well as the orchestrations of them distributed to jazz bands around the country. A very popular book for orchestras was his 1926 Dance Encores with arrangements of many popular old waltzes, one steps, two steps and fox trots scored for ensembles of varying sizes. He also worked on a piece with the popular cartoonist Rube Goldberg, based on one of his characters, Boob McNutt. While not the runaway hit that Barney Google from the same era had been, it still did well by the composers and Mills. In the 1930 census Jeannette and Frank, again as Henri, were lodging at 550 West 158th Street near Harlem, and he was listed as a musician with a music publishing company.

with a little assistance from another busy uke arranger, May Singhi Breen. One of the earliest books on Jazz performance was written by Klickmann in 1926 and published by Mills. He also had a hand in many of the novelty numbers put out by the firm, as well as the orchestrations of them distributed to jazz bands around the country. A very popular book for orchestras was his 1926 Dance Encores with arrangements of many popular old waltzes, one steps, two steps and fox trots scored for ensembles of varying sizes. He also worked on a piece with the popular cartoonist Rube Goldberg, based on one of his characters, Boob McNutt. While not the runaway hit that Barney Google from the same era had been, it still did well by the composers and Mills. In the 1930 census Jeannette and Frank, again as Henri, were lodging at 550 West 158th Street near Harlem, and he was listed as a musician with a music publishing company.

with a little assistance from another busy uke arranger, May Singhi Breen. One of the earliest books on Jazz performance was written by Klickmann in 1926 and published by Mills. He also had a hand in many of the novelty numbers put out by the firm, as well as the orchestrations of them distributed to jazz bands around the country. A very popular book for orchestras was his 1926 Dance Encores with arrangements of many popular old waltzes, one steps, two steps and fox trots scored for ensembles of varying sizes. He also worked on a piece with the popular cartoonist Rube Goldberg, based on one of his characters, Boob McNutt. While not the runaway hit that Barney Google from the same era had been, it still did well by the composers and Mills. In the 1930 census Jeannette and Frank, again as Henri, were lodging at 550 West 158th Street near Harlem, and he was listed as a musician with a music publishing company.

with a little assistance from another busy uke arranger, May Singhi Breen. One of the earliest books on Jazz performance was written by Klickmann in 1926 and published by Mills. He also had a hand in many of the novelty numbers put out by the firm, as well as the orchestrations of them distributed to jazz bands around the country. A very popular book for orchestras was his 1926 Dance Encores with arrangements of many popular old waltzes, one steps, two steps and fox trots scored for ensembles of varying sizes. He also worked on a piece with the popular cartoonist Rube Goldberg, based on one of his characters, Boob McNutt. While not the runaway hit that Barney Google from the same era had been, it still did well by the composers and Mills. In the 1930 census Jeannette and Frank, again as Henri, were lodging at 550 West 158th Street near Harlem, and he was listed as a musician with a music publishing company.The demand for the services of musicians slacked only slightly in the 1930s, and less so in Manhattan. Just the same, Frank was not composing very much any longer, but continued to work for Mills on staff, then later free-lancing for anybody who could use his talent. In the 1940 census taken in Manhattan, he was still listed as an arranger and composer of music. Frank's 1942 draft record shows him as self-employed and working for "various music publishers." The couple had moved south a little to 561 W. 141st Street where he would spend the rest of his life. He was known to have edited a drumming folio by the young Buddy Rich in 1942 and The Modern Trombonist by Tommy Dorsey around the same time. In the 1940s and 1950s Klickmann spent some time co-leading one popular swing/jazz group with trombonist Fred Norman for both live appearances and some recording sessions, including backing female singers Irene Redfield and Millie Bosman. He was also a member of the governing board of the American Accordionists Association. The 1950 census taken in Manhattan showed Frank still working as a composer and arranger for music publishers. Frank retired for the most part in the mid-1950s, living in Manhattan until his death. He passed on at Knickerbocker Hospital in New York in 1966 at age 81. Coincidentally, his sister Ida passed that same week in Chicago.

While certainly important as a composer contributing to the ragtime era and beyond, his arranging on standards as diverse as Ragtime Cowboy Joe, Under the Double Eagle and Song of India helped define popular or "pop" music before there was a term for it. He had a talent for making a piece sound rich and complex while keeping it very playable for the average pianist consumer. His popularization also extended beyond that with good orchestrations, adaptations, and even often-misunderstood instruments such as the accordion. His early work with non-jazz saxophone arrangements when the instrument was still fairly new was important in promoting more widespread utilization of the instrument. So while Klickmann wrote some good rags and ragtime songs, he can be remembered for so many more areas of music to which he contributed.