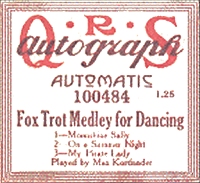

Max Kortlander was a composer on a roll. In fact, on several rolls. His role with rolls was truly instrumental in the history of automated and hand-played music of the 1920s to 1950s. Due to his association and career with QRS, any biography of Max Kortlander necessarily needs to include a history of QRS during his tenure, as well as the remarkable work and legacy of his prime arranger, J. (Jean) Lawrence Cook.

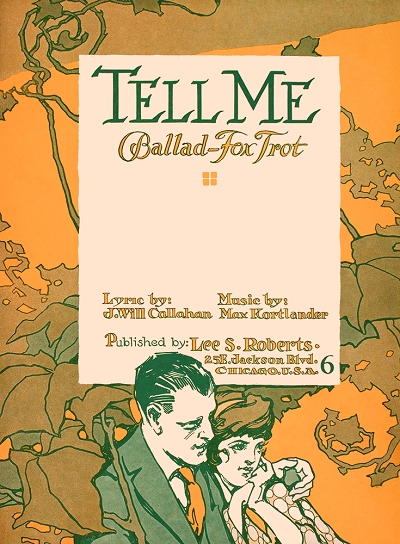

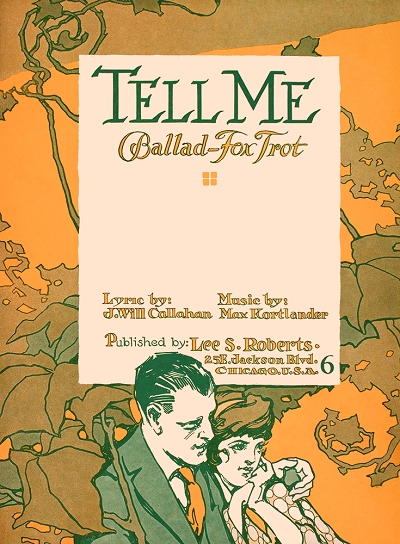

Max was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan to Joseph Kortlander and Elizabeth M. Boxheimer. He was one of seven children, including older sisters Marguerite (7/1887) and Lois (3/1889), younger sister Dorothy (1/1892), and brother Herman Rudolph (5/21/1900). Two more of his siblings died at an early age, including John (2/1895), who was listed in the 1900 census, but not in subsequent records. Note that on the cover of Tell Me his middle initial is shown as D., but on the 1920 census and two other historical records it is clearly J., very possibly for Joseph or John.

Joseph Kortlander was a wholesale liquor merchant, in business with his brothers William, Theodore and George, all part of a well regarded family in Grand Rapids. From an early age it was clear that Max had a degree of natural music talent. In a house where there had always been a piano, and there were reportedly four grand pianos in the 1910s, as his mother and her sisters were also musically inclined and even taught piano, music was hard to avoid. According to Herman, they were all Mason and Hamlin pianos, and were in the family for many decades. Elizabeth was more than just Max's first piano teacher, adding composition to the home curriculum once he had gained some playing skill. Max was encouraged to write at least two simple songs every day. He reportedly did not enjoy the technical aspects of learning piano, but relished the compositional part.

In a house where there had always been a piano, and there were reportedly four grand pianos in the 1910s, as his mother and her sisters were also musically inclined and even taught piano, music was hard to avoid. According to Herman, they were all Mason and Hamlin pianos, and were in the family for many decades. Elizabeth was more than just Max's first piano teacher, adding composition to the home curriculum once he had gained some playing skill. Max was encouraged to write at least two simple songs every day. He reportedly did not enjoy the technical aspects of learning piano, but relished the compositional part.

In a house where there had always been a piano, and there were reportedly four grand pianos in the 1910s, as his mother and her sisters were also musically inclined and even taught piano, music was hard to avoid. According to Herman, they were all Mason and Hamlin pianos, and were in the family for many decades. Elizabeth was more than just Max's first piano teacher, adding composition to the home curriculum once he had gained some playing skill. Max was encouraged to write at least two simple songs every day. He reportedly did not enjoy the technical aspects of learning piano, but relished the compositional part.

In a house where there had always been a piano, and there were reportedly four grand pianos in the 1910s, as his mother and her sisters were also musically inclined and even taught piano, music was hard to avoid. According to Herman, they were all Mason and Hamlin pianos, and were in the family for many decades. Elizabeth was more than just Max's first piano teacher, adding composition to the home curriculum once he had gained some playing skill. Max was encouraged to write at least two simple songs every day. He reportedly did not enjoy the technical aspects of learning piano, but relished the compositional part.Even though his mother and sisters were trained in the classical music styles of the 18th and 19th centuries, Max preferred to look ahead, listening to and trying to emulate the latest popular song and ragtime styles. By the time he was in his early teens, his skills were considerable enough that he was able to play around Grand Rapids in select venues to earn some cash as well as hone his performance skills.

Once Max left high school he attended Oberlin College Conservatory in north-central Ohio during the 1908-1909 school year. He then switched to the American Conservatory in Chicago, Illinois for the remainder of his higher education in advanced piano studies. In the April 1910 enumeration he was shown still living with his parents and siblings, in Grand Rapids, perhaps during a transition between school and career. While Max listed no profession, his sister Marguerite was listed as a musician and music teacher. Back in Chicago by 1911, Kortlander earned money for his schooling by performing all types of music from classical to popular at posh supper clubs, dance venues, and even as an accompanist on occasion. It was most likely in Chicago that he made the connections that would define his future performing career.

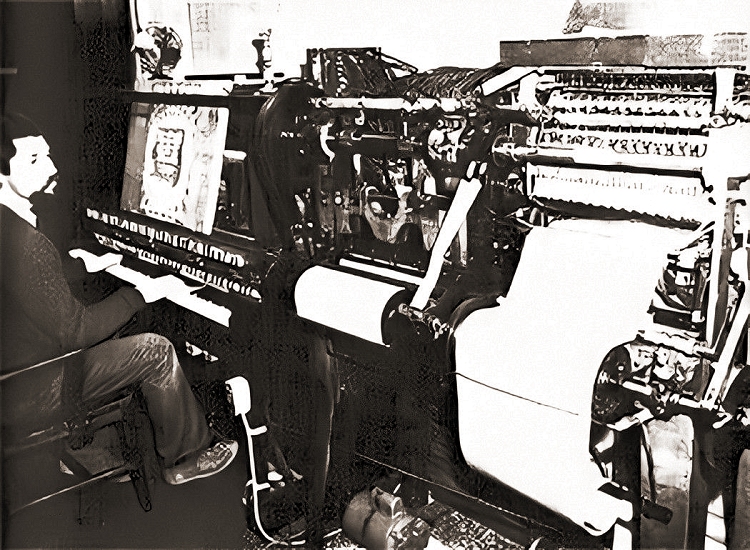

After having continued to play for a while upon completion of his schooling, Max was approached by somebody from the player piano roll division of the Melville Clark piano company, most likely arranger Lee S. Roberts or sales director, later company president, Thomas M. Pletcher. They asked him to join QRS as a performer in 1914, two years after they started making "hand-played" piano rolls, with their famous marking piano and around the time they had improved their mass perforators for higher volume. Max quickly became one of the QRS playing stars, and he would spend the rest of his life associated with that label in an important capacity. He very soon became the manager of the recording department as well, and a top arranger.

They asked him to join QRS as a performer in 1914, two years after they started making "hand-played" piano rolls, with their famous marking piano and around the time they had improved their mass perforators for higher volume. Max quickly became one of the QRS playing stars, and he would spend the rest of his life associated with that label in an important capacity. He very soon became the manager of the recording department as well, and a top arranger.

They asked him to join QRS as a performer in 1914, two years after they started making "hand-played" piano rolls, with their famous marking piano and around the time they had improved their mass perforators for higher volume. Max quickly became one of the QRS playing stars, and he would spend the rest of his life associated with that label in an important capacity. He very soon became the manager of the recording department as well, and a top arranger.

They asked him to join QRS as a performer in 1914, two years after they started making "hand-played" piano rolls, with their famous marking piano and around the time they had improved their mass perforators for higher volume. Max quickly became one of the QRS playing stars, and he would spend the rest of his life associated with that label in an important capacity. He very soon became the manager of the recording department as well, and a top arranger.In 1911, perhaps just before moving to Chicago, Max married Jean Jones of Grand Rapids, Michigan, nearly four years his senior, and the daughter of the co-owner of Berkey and Jones furniture factory. Their adopted son Stephen C. Kortlander was born on January 16, 1917 and came into their lives shortly after that. (That date is according to Social Security records - a 1934 passenger manifest shows January 20, 1918, which would be incorrect given the following information:). On his June 1917 draft record, which incorrectly shows 1891 as his birth year, Kortlander lists himself as employed by the Melville Clark Piano Company in Chicago, and as the sole support for his wife and child. He further listed physical unfitness of an unknown nature as a potential reason for not serving in the military.

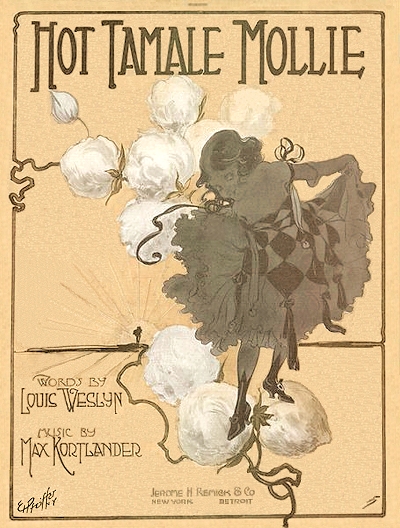

Working with music as he did, and given his playing talent, it was natural that Max would be tapped either by himself or his peers as a composer. Starting in 1917 he started releasing compositions both on rolls and in printed form. A few of his early songs were written with prolific blind lyricist J. Will Callahan. His first big hit was Tell Me, published initially in Chicago in 1919 by his boss Lee Roberts, and quickly adopted by New York's most popular performer, Al Jolson. Jolson's recording of the work and subsequent sales were responsible for much of Max's early prosperity, especially when he sold the tune to publisher Jerome H. Remick that same year for a princely sum (over $70,000 and perhaps up to a reported $100,000). In September, both Roberts and Kortlander packed up their families and moved to New York City to expand the QRS empire.

Max continued writing in addition to his arranging and performing duties, although it would be a while before he saw another hit the size of Tell Me. his songs Like We Used To Be and Anytime, Any Day, Anywhere did fairly well for him in 1920, as did Bygones in 1922. His early efforts readily gained him a membership in ASCAP in late 1920. In the January, 1920, enumeration Max and his family were shown living in the prosperous area of White Plains, Westchester County, New York, and he listed himself as a musician and a manufacturer of player piano rolls. The Kortlander's only other child, adopted daughter Jean Elizabeth Kortlander, was possibly born on January 20th, 1920 (the previously mentioned ship manifest shows February 20, 1923, at odds with the official Social Security record, but could be an adoption date). That same year QRS opened a new production facility in the Bronx borough of New York City, as highlighted in the Music Trade Review of October 2, 1920. Most of the article is reproduced here for a better idea of the environment in which Kortlander was working, and would eventually take over:

NEW MODEL MUSIC ROLL CUTTING PLANT OF Q R S CO.

Big Factory in the Bronx Most Modern in Every Particular, With Plenty of Daylight, Latest Machine Equipment, Direct Shipping Facilities and Other Important Features to Stimulate Production — New York Now Made the Headquarters for the Company's Recording Work

Big Factory in the Bronx Most Modern in Every Particular, With Plenty of Daylight, Latest Machine Equipment, Direct Shipping Facilities and Other Important Features to Stimulate Production — New York Now Made the Headquarters for the Company's Recording Work

|

The new modern plant of the Q R S Music Co., located at 135th street and Locust avenue, New York, is now operating under practically full capacity. It is under the personal management of Lee S. Roberts, vice-president of the Q R S Music Co., whose experience in the manufacturing of music rolls has been of long duration and whose authority on proper merchandising is generally acknowledged.

...This plant, which is of the most modern construction, is a five-story fireproof structure, with daylight pouring in on all four sides, giving the entire interior enough light so that artificial illumination is practically unnecessary in any part of the building. In order that this daylight plant will never be obstructed by nearby buildings and also in order to allow for future expansion, the Q R S people purchased the entire block, bounded by 134th street, 135th street and by Locust avenue and Walnut street.

The plans of the building have been so arranged as to allow the construction of a duplicate plant on the block, whenever the demand for Q R S music rolls becomes sufficient to demand such an expansion. The new building has a floor space of approximately one hundred thousand square feet.

The executive offices are located on the top floor, access to which is gained by the passenger elevator just inside the main entrance. Besides the executive offices there are also the recording rooms, the cafeteria and rest rooms on the fifth floor. The recording rooms are built in the most modern style, with heavy partitions separating them, in order to make them absolutely sound-proof. In this way recording can be going on in any or all of the rooms at the same time without interference.

The recording is in charge of Max Kortlander, who has transferred practically all of the recording work from the Chicago factory to New York. Among those who may be found using these recording rooms are such popular pianists as Victor Arden, Russell Robinson, Phil Ohman and Pete Wendling. Another nationally known pianiste who is often present is Mme. Sturkow-Ryder, of Chicago, who assists in playing and editing Q R S story rolls. Mme. Marguerite Volavy, widely known as a concert pianiste, and whose splendidly edited reproducing rolls have made her name and musicianship well known to thousands of instrument owners, has charge of the reproducing roll department. This department is one of distinct importance in the Q R S organization and is housed in handsome offices especially constructed for its particular requirements.

The cafeteria is one of the finest examples of modern lunch-rooms for employes [sic]. It is capable of taking care of the entire factory force, which now numbers over five hundred, during the noon hour. The meals are sold at cost, and an idea of the popularity of the place may be gained from statistics which show that 95 per cent of the employes [sic] take advantage of this delightful place to sojourn during the noon-hour.

The second, third and fourth floors are devoted to the manufacture of music rolls. On these floors twenty or more of the most modern double perforating machines have been installed. For the handling of the cut sheets, and for the boxing of same, the most up-to-date labor-saving devices have been introduced. An idea of efficiency in this plant can be gained from its capacity output, which is thirty-five thousand rolls per day. All of the machinery is electrically operated and is practically noiseless in operation.

The ground floor is used for storage and shipping. The rolls are stored on racks especially designed for the purpose, which have a capacity of more than eight hundred thousand rolls. The shipping room is designed so that as orders are filled the factory trucks can be pushed directly into freight cars on the company's double-track siding, or upon motor trucks which back inside of the building to the loading platform.

There, is no doubt but this factory will be able to take care of and give prompt attention to the increasing demand for Q R S rolls. It is a splendid addition to the Q R S chain of factories, extending from coast to coast, the other factories being in Chicago and San Francisco.

Another fine performer and songwriter, Pete Wendling, had joined QRS a couple of years after Max, but had already been living in New York City. The pair got together after Max relocated, and soon started writing tunes together, creating a bounty of them both on rolls and in printed form. Max and Pete were two of the bigger stars of QRS in the 1920s, arguably even more popular than their boss, Lee S. Roberts. Another star of both piano rolls and recordings, soon to conquer radio, was former Imperial and Ampico employee Lewis J. Fuiks, now working as Victor Arden. Max and Victor, who did several rolls together, recorded a pair of duets in 1920 on the Pathé label, the only commercial audio recordings completed by Kortlander.

Pete was working for composer/publisher Irving Berlin at that time, so most of the co-written works went through Berlin. However, Max signed on with a different publisher for his own works, as announced in the Music Trade Review of April 28, 1923: "Max Kortlander, general manager of the recording department of the Q R S Music Co., has closed a contract with Jack Mills, Inc., whereby that firm will publish all his piano compositions for a period of two years. The first of these new releases has been added to the Mills 'Pianolog Series' and are entitled 'Deuces Wild' and 'Red Clover.'"

Other stars in the QRS universe included Lee S. Roberts, stride pianist Thomas "Fats" Waller, and novelty composer Zez Confrey. However, one additional primary roll artist, more of a prominent background figure in a sense, would join QRS, and would not only help to keep the company alive in future years, but would take on multiple performer's personalities in the process of doing so. In 1923, Max helped facilitate the signing of J. Lawrence Cook to QSR. Cook and Kortlander would become the core of QRS by the end of the decade. While Max was good at playing and editing the markups he created, Cook became expert at his own marking piano, which allowed him to punch the rolls in step time rather than real time, even four-handed rolls. Cook also had a gift of being able to imitate the style of pretty much any pianist from a recording or live performance. While this has caused some confusion and speculation among historians about what was a Cook edit of somebody else's performance and what was entirely Cook's work, including on rolls with Kortlander's name, it helped QRS to steadily grow in popularity and consistency, eventually dominating the piano roll industry by the late 1920s.

QRS under Pletcher and, and often either with the assistance of or against the advice given by Kortlander, branched into other areas of music production as well in the 1920s, including a sponsored involvement in radio programming which went over well with fans, and likely sold additional rolls, although in spurts. One such venture was reported on in the Music Trade Review of August 2, 1924, when radio broadcasting was still fairly new:

Applause letters from radio fans in all sections of the country are pouring into the office of WGR, broadcasting station of the Federal Telephone & Telegraph Co. here [Buffalo, New York], expressing delight over the recent Q R S musical program arranged by Bob Hollinshead, local manager of the roll company's distributing warerooms. The program was sent through the ether Monday night, July 21 [1924]. Q R S artists, composers and singers of international note took part in the program, which is proclaimed by scores of fans, and by the vast audience in the ballroom of the Statler Hotel from where the program was broadcasted, to be one of the most artistic and entertaining programs ever heard outside of New York City.

It was announced at the beginning and close of the program that selections being heard were obtained on Q R S rolls.

Special invitations were issued by Mr. Hollinshead to scores of persons in Buffalo who owned player pianos, but who did not own a radio, to attend the concert given in the ballroom of the hotel. An invitation was also extended the New Thought Alliance convention which was being held in the hotel, thereby filling the ballroom to capacity with an appreciative representative audience. Sales persons from roll departments of music stores of the city were also present.

Peter Wendling, Max Kortlander and Victor Arden, well-known songwriters and makers of Q R S rolls, were sent by the company to Buffalo to head the program. Their piano selections were followed by deafening applause from the audience and hundreds of letters from fans expressed particular interest in these three artists...

The three composers and artists sent from New York by the Q R S Co., Messrs. Kortlander, Arden and Wendling, visited the trade following the concert and witnessed hundreds of sales of their rolls and autographed many rolls for purchasers. Mr. Hollinshead said that success of the concert greatly exceeded his expectations and sales in Q R S rolls took a spurt on the day immediately following the concert. Fan letters were replete with such expressions as "Come again, Bob Hollinshead," "Give us a little more of this sort of thing," "I have just heard one of the most professional concerts ever received by my radio."

Kortlander and Cook worked diligently during the second half of the 1920s to make QRS the clear leader in the industry. The company was able to buy up faltering concerns from time to time, including Connorized, Vocalstyle, U.S. Music and Imperial.

They then reissued many of the better rolls they acquired in the QRS catalog, some after minor tweaking by one of the editors. But in order to stay current, Max and his gang also had to keep pace with the publishers and do what they could to speed up the process of roll production. While it was hardly the rule, there was at least one exceptional instance in which they absolutely steamrolled a roll into production, as noted in the Music Trade Review of October 9, 1926:

|

Twenty-four hours after Max Kortlander, recording manager for the Q R S Music Co., received the big Triangle Music Co.'s song hit, "The Miami Storm," he had word rolls all made and ready for shipment. This is said to be the first time that anything like this has been accomplished in the music roll industry and it shows the confidence the Q R S Music Co. has in this new waltz song. Joe Davis, head of the Triangle Music Co., feels sure he will have a sensational sheet music, record and roll seller in this new publication.

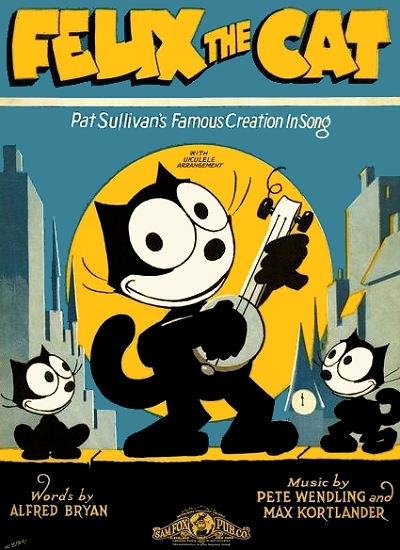

In spite of his successes both as a composer and arranger, Max's responsibilities in running the roll department at QRS and also participating in public relations for the firm started to overtake his other musical pursuits. He and Wendling had composed infrequently starting in 1922, but their two pieces from 1926 comprised half of Kortlander's dwindling output. Between 1916 and 1926, Max had recorded and/or edited approximately one thousand rolls. Many were released under the pseudonyms of Ted Baxter and Jeff Watters. Max also used these additional names when he did extra passes to record four-hand arrangement and needed to infer that there was a second performer playing with him. Also, sensitive to the impact of race on sales, he used names that the white public of the 1920s would deem more acceptable when they were less sure about pieces recorded or written by black artists. However, Kortlander's steady output also started to drop. The exact time line is uncertain, but it is likely that most of the rolls from 1927 and all of them from 1931 forward with Max's name on them were actually arranged by Cook. Max was still composing, however, and in 1928 with Pete and their friend Alfred Bryan, they released a musical tribute to the most famous feline of the silent cartoons, Pat Sullivan's Felix the Cat.

In addition to the difficult task of acquiring other companies and assimilating their products into the QRS line, Max also helped manage QRS operations in San Francisco, California; Toronto, Canada; and Sydney, Australia. There were external headaches to deal with as well, including one case of an imposter reported on in the Music Trade Review of May 26, 1928:

The Q R S Co., Chicago, reports that last week a party representing himself to be Max Kortlander, of the Q R S Co., and claiming to be checking up on royalties, was working in Cincinnati. This party is of light complexion, about five feet seven and a half inches, weighs about 160 pounds and has a cheap printed card with just "Max Kortlander" printed on it.

The real Max Kortlander is recording manager of the Q R S roll department, makes his headquarters at the company's New York plant and has not been in Cincinnati for over a year. He is about six feet tall, dark complexion and weighs about 190 pounds.

The Q R S Co. is unable to ascertain what this person's object is, and has wired Cincinnati to try and locate him. The company also would appreciate a wire at the Chicago office sent collect notifying if this party visits any music store on this mission.

|

At some point in the mid-to-late 1920s, Kortlander's marriage was also a casualty of work. Max and Jean separated at some point between 1928 and 1929. In the 1930 census he was shown still living in Westchester as a composer of music. His status indicated that he was still married, but Jean and the children seemed to have evaded the 1930 enumeration. They surfaced soon after in Santa Barbara, California, and all three resided more or less in Southern California for the rest of their lives in homes bought for them by Max. It appears that Jean never remarried, having died in November 1975 down the coast in Pacific Palisades as Jean Kortlander, according to her Social Security record.

The Great Depression could easily have dealt a fatal blow to QRS in 1930 or 1931. They were already coping with dropping sales. After a sales peak year of around 200,000 player pianos in 1923, the saturation of automated instruments in the home was able to sustain increases in QRS sales for around four years, peaking at around ten million units in 1927. But other media were competing with piano rolls and making them less viable to an increasingly sophisticated musical consumer.

The first of these was radio, which made great advances between 1922 and 1927 in both the quality of the instruments and the broadcast content. Radio led directly to the advent of electrical recordings around 1925, which represented a leap in audio quality over the previous acoustically recorded discs. By 1927, the sales of electric radio-phonograph units was far outpacing that of player pianos. After an earlier merge with the Z-Nith Electronics Company, QRS put forward their superior line of "Red Top" radio tubes. However, the tube business did not work out as well as Pletcher hoped, brought down in part by patent suits from Raytheon. The radio and tube business was spun off into what became the Zenith Corporation with Pletcher as a vice president, but QRS had no licensing stake in it and therefore reaped none of the rising Zenith profits. Another effort was made by Pletcher to keep pace with the trend to diversify, and in early 1929 he merged QRS Music with the DeVry Company, a camera manufacturer. The combined concern now was involved in the production of neon signs, DeVry still cameras, home movie cameras and projectors, and even a short-lived record label with three different lines from 1928 to 1930.

Sound films had entered the picture, overtaking the film industry between 1927 and 1929. Given the price of piano rolls, which were often a dollar or more, and comparing that with other entertainments, including cheaper records that did not require manual pumping to play, movies for ten cents that were changed often at the local theater, and radio which was ostensibly free once the radio had been acquired, piano roll and sheet music sales had started to suffer even before the Wall Street crash of October 1929.

Pletcher found himself in increasing difficulties in the business, and Max found himself stepping up to the plate more often to help with the decisions. Then he made the biggest decision of his professional life.

|

QRS-DeVry was heading into bankruptcy in 1931. Pletcher's heavy investment in Zenith stock took it's toll after the crash, and he had to sell off all of the remaining QRS-DeVry divisions or let them go into receivership. Max took advantage of this situation because he knew QRS was the only viable piano roll company still alive, and he truly believed in his product. So Kortlander mortgaged his Westchester home, combined it with much of his earned fortune, and leveraged a buyout for the roll division of the company. Then he put it into a reorganization mode, as reported in two notices in the August, 1931, Music Trade Review:

NEW MUSIC ROLL CONCERN

Max Kortlander, of the QRS-DeVry Corp., New York, is the head of a new company recently organized to take over the music roll business of that organization. The new concern began functioning on July 1 and already there has been a gratifying response from dealers and others in the trade to the company's initial campaign.

Mr. Kortlander, who has been connected with the QRS Co. division for the past fifteen years, has a thorough understanding of all departments of the business and is firm in the belief that there is an opportunity for a substantial increase in music roll sales provided both manufacturers and dealers show a proper amount of interest in player pianos and their servicing. As a matter of fact, he holds there is a big roll market lying at the dealer's door right now among people who own player pianos but have stopped buying rolls because no attempts have been made to sell them. The manufacture of rolls will be conducted in the QRS factories both in Chicago and New York, Mr. Kortlander making his headquarters in [New York] city.

CHANGE OF EXECUTIVES OF THE Q R S-DEVRY CO.

A number of changes in executives have recently been made in the Q R S-DeVry Co. The general offices are now located at the factory, 4829 South Kedzie avenue, Chicago. Thomas M. Pletcher resigned as president, but not as director; Treasurer Barclay was succeeded by J. V. Kleckner, who becomes vice president and general manager. Chas. Kunzer is general sales manager.

The music roll business of the QRS Co. including the equipment, master rolls, etc., has been sold to the Imperial Industrial Co., of New York City, Max Kortlander, president. Mr. Kortlander is well known as a veteran of the music roll business, and for years was the technical head of the QRS roll plant. It is understood that he made this purchase for himself and business associates and has already announced his intention to increase the interest of the public and the trade in player-piano rolls. The QRS catalog contains many thousand selections, embracing all classes of music.

The Imperial Industrial Corporation was named that because if the roll business did fail, Max would be able to change their product without changing the name. The business model for QRS under Kortlander and Imperial Industrial changed nearly overnight. There were no more hand-played rolls, such as those made popular by artists such as "Fats" Waller. From that point on for over three decades, the rolls were hand arranged by J. Lawrence Cook, often augmented by at least one other staff arranger. With fewer arrangers and no players, perforators, which were sometimes expensive to maintain, were sold off.

The business model for QRS under Kortlander and Imperial Industrial changed nearly overnight. There were no more hand-played rolls, such as those made popular by artists such as "Fats" Waller. From that point on for over three decades, the rolls were hand arranged by J. Lawrence Cook, often augmented by at least one other staff arranger. With fewer arrangers and no players, perforators, which were sometimes expensive to maintain, were sold off.

The business model for QRS under Kortlander and Imperial Industrial changed nearly overnight. There were no more hand-played rolls, such as those made popular by artists such as "Fats" Waller. From that point on for over three decades, the rolls were hand arranged by J. Lawrence Cook, often augmented by at least one other staff arranger. With fewer arrangers and no players, perforators, which were sometimes expensive to maintain, were sold off.

The business model for QRS under Kortlander and Imperial Industrial changed nearly overnight. There were no more hand-played rolls, such as those made popular by artists such as "Fats" Waller. From that point on for over three decades, the rolls were hand arranged by J. Lawrence Cook, often augmented by at least one other staff arranger. With fewer arrangers and no players, perforators, which were sometimes expensive to maintain, were sold off.In addition to making their own piano rolls and the new Imperial label, Imperial Industrial produced rolls for the few smaller concerns that were still around, with the exception of Aeolian who still used their own plants. They also used some of the same equipment to make rolls for automated office printers. Also in 1931, Max recruited his younger brother Herman, who had lost his job at a Grand Rapids newspaper, to help him manage the new concern through a variety of front office responsibilities. Most of the support staff was let go, but a few of the perforator specialists, all men, were retained, as was a minimal staff of around 25 low-paid women who helped with packaging and secretarial duties. The staff was beefed up only in the fall anticipation of increased holiday volume.

Max also realized that the promotion of the largest remaining roll company and the value of their product had not been well handled. He also realized there was probably only enough business during the financial crisis to keep just one roll company alive, and without current product that would never happen. J. Lawrence Cook was literally instrumental in keeping the product line current and vital, with the help of a few other selected arrangers throughout the next three decades. But to sell the product, now that he had cut costs, Max started wholesaling piano rolls at 25 cents each. This allowed the dealers to sell rolls from 33 to 50 cents each, which brought in customers who still wanted to enjoy old classics or the latest hits on their home piano. At a time when a good meal was a necessary commodity at 25 cents, a piano roll that sold for any more than that was considered a luxury, but it was one that many customers continued to enjoy. Kortlander was able to pay back on his mortgaged home in less than two years.

While the market for the more elaborate reproducing pianos, such as Duo-Arts and Ampicos, was only a small piece of the automated music pie, Max still saw an opportunity in that market for the third major reproducing system, the first one on the market, and bought it, as announced in the Music Trade Review of December, 1932:

IMPERIAL INDUSTRIAL CORP. MAKE WELTE-MIGNON ROLLS

The Imperial Industrial Corp. of New York and Chicago, which was organized a year or more ago with Max Kortlander as president, has taken over the manufacture and distribution of the Welte-Mignon (Licensee) reproducing rolls and since December first has been taking care of dealer demands for that product. The corporation has, for some time past, been manufacturing QRS and Imperial rolls, having taken over that department from the QRS-DeVry Corp. The Chicago offices are at 4829 Kedzie avenue and the New York headquarters, where the cutting is done, in the modern plant at Walnut avenue and 136 East 135th street.

In a 1985 interview with Bill Burkhardt, Herman was asked about the Welte-Mignon acquisition. "Max bought the Welte rolls and machines and that was it. These companies were failing. We bought a lot of different companies, junked the machines and used the stock. That's all you could do. We couldn't carry on because they were losing money.

|

"It was a good machine, and they had a lot of good expensive, classical masters. Good ones. They were different masters. You couldn't play them on a regular standard player piano. The notes would sound at the top and bottom. They indented in farther in the roll, you know. Although, QRS made the Recordo [a very basic expression system developed by Wurlitzer], the expression wasn't as elaborate as Welte or the AMPICO or the Duo-Art."

While he had buckled down during the Depression, Herman said his brother still enjoyed the fruits of his arduous labors. After the hectic holiday season they often retreated to Florida for a month at a time. Appreciative of his opportunities and his life, Max was also a social host who enjoyed giving parties complete with good entertainment, sometimes in conjunction with promotional events. He avoided anything ostentatious, perhaps aware that publicity focusing on lavish expenditures might alienate consumers and dealers alike. He simply invested well and treated his employees well. Having divorced in 1931, Max remarried in 1933 to Gertrude (Williams) Begoon, acquiring a stepson, Jackson Begoon in the deal. Gertrude was also well-liked by most QRS personnel. They, along with Max's own adopted teenage children, took a two week cruise to Europe in the winter of 1934 aboard the Mauretania.

The most important and fruitful relationship that Max had was also perhaps the trickiest one to maintain. J. Lawrence Cook loved his work, and without it QRS clearly would not have survived the Great Depression. Given that he was black, and being cognizant of the climate of race relations in the United States in the 1930s, theirs seemed to more a relationship of respect than anything else. Cook did pretty much whatever was asked of him, including rush jobs, rearrangements of older pieces, or direct imitations of audio recordings. Yet based in part on recollections of some personnel, and a CBS television show in which they appeared, it also appeared that their roles were defined as Lawrence and Mr. Kortlander.

Although the exact figures and the context of when they apply are hard to pinpoint, Herman talked about Cook's pay and a couple of other aspects of his tenure with QRS: "Well, [he was not paid] a great deal. Maybe $50 or $60 a week [in the early 1950s]. I mean, he was satisfied, so that was it. It was a good salary. The factory girls only got $20 a week. He worked at the Post Office. He was working for the pension, and he was doing all right. That was after hours, too, in the evening. He worked for us all day." Cook recalled something similar, but noted that in later years he was making around $200 per week. Given the number of people that Max had laid off, Cook long considered himself to be one of the lucky few who was spared.

|

Concerning his particular talents at his specialized roll markup piano, particularly after the abandonment of "hand-played" rolls, Herman remembered: "There were no hand-played rolls. They had to cut corners all the way. Cook marked them out on paper in the beginning, pen and pencil, then he had another machine that could cut them out. We had another fellow to do that. But they gave that up later." Cook's talent with a pencil, or in creating his arrangements in incremental step time should not regarded lightly, and same goes for his extraordinary marking piano. On this device Cook recorded more piano rolls than any other single artist in the history of automated music. The piano is still kept at QRS in Buffalo, New York, and was reportedly used by staff arrangers until the end of the 1980s.

By the same token, Max, whose name was still appearing on rolls thanks to Cook's emulation of his style, did not totally abandon his musical acumen in exchange for micromanaging a struggling business. He had a hand in choosing the content that QRS put out, whether they were re-arrangements of older tunes or current pieces being pushed by publishers. His experience and intuition were well enough developed that he could see how a piece was being promoted by a publisher or how the public might respond to it on radio and record, and was therefore selective enough to have Cook and other arrangers produce rolls that were also usually popular and sold well. Speed was also paramount, as they wanted to get rolls on the market while a hit song was still on the Billboard charts.

There were a few other primary arrangers that worked for QRS along with or under Cook. From 1940 to 1947 there was Frank Milne (pronounced Mil-nee), who had record for Rythmodik and Aeolian. He did a particularly fine job with ballads, and in reimaging many older tunes in new styles. Living in Belmar, New Jersey, Milne had a commute of around two hours each way, but was dedicated to his work nearly until his death from smoking-induced lung cancer. Another veteran was Rudy Erlebach, who had enjoyed over two decades of experience when he succeeded Milne at QRS in 1947. He worked for them sporadically until his death around 1955. Dick Watson was hired 1961 to arrange current popular tunes, and worked through the end of the decade. Herman Babich (a.k.a. Hi Babit) was hired almost simultaneously with Dick, and continued the QRS arranging legacy after Max's death, working from 1960 to around 1967. Another musician who paralleled Babit's tenure was Rudy Martin, starting there in 1964 to help run machinery, and continuing from the late 1960 into the 1990s as an arranger. There was only the one punching piano, so all of the arrangers had to do some time sharing.

Kortlander continued to write and publish compositions sporadically until around 1940. His last known published work, Something to Live For, was a dynamic ballad that was recorded by a number of artists over the next two decades, including Judy Garland, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. At fifty-years-old Max decided to focus entirely on business, and the next business at hand was the shot in the arm that both QRS and the United States needed. For the 1940 enumeration, Max, Gertrude and Jackson were living with two servants in Rye, Westchester County, New York, with Max appropriately lists as the President and manufacturer of "Piano Player Rolls."

The economic recovery was already underway in 1940 and 1941 as America looked towards Europe and the ongoing war there. As the U.S. started gearing up for what seemed to be inevitable, the increase in the defense industry activity put more money into the economy, and luxury items again were less out of reach. On the other side of the coin, many player pianos were 25 to 35 years old at that point and in need of repair, while new ones were not being built, the Depression having shut down that part of the industry. Still, the majority of automated pianos built in the bustling 1920s were operational, and Kortlander saw the opportunity to not only continue as they had over the past decade, but even expand a bit by playing to the current world situation.

|

During World War II, QRS kept the country supplied in new arrangements of stirring patriotic songs and marches, the latest big band swing pieces, and other popular works. Some sacrifices had to be made to get product out there since there were metal and rubber shortages. So rolls needed to be taped with a special rig, and steel eyelets were temporarily replaced by cardboard. The boxes were made of a cheaper cardboard as well, and without the colorful printed paper covering. But according to Herman Kortlander: "We could get paper, but we couldn't get the manufacturer to do the work. They didn't have help. Men had gone to war or were working in war factories. So we did have difficulties, and it was the busiest time, too. We sold more rolls! It was like the old days. We sold something like 5,000 rolls a day, and we had all 3 perforators running all day long, and overtime pay, and extra girls to assemble the rolls and fill the orders."

Directly after the war there was another lull in sales as the country settled down. There were more cutbacks in the late 1940s. Then nostalgia in music became the rage. Post-war America was in a bit of a musical identity crisis, since there was no particular popular form that dominated. Swing had become be-bop, rhythm and blues were not yet rock and roll or culturally accessible to much of the white population, and the crooners were less inspiring during this period. Then came the phenomenal success of the 1948 recording of Pee Wee Hunt's band playing 12th Street Rag, and the subsequent resurrection of ragtime in general thanks to Lou Busch and Capitol Records. He was joined by Johnny Maddox, Frankie Carle, Marvin Ash, and other fine pianists, in making the new generation of Americans, made up in part by WWII veterans, yearn for and enjoy the happy music of their youth.

Max saw and seized on this opportunity, and was helped out musically as well. In 1949 composer Cy Coben composed The Old Piano Roll Blues. Whether this was spontaneous or commissioned by Aeolian, Wurlitzer or QRS has been hard to lock down. However, it was around this same time that Aeolian and Wurlitzer introduced new electrically driven and more compact player pianos. QRS was right there with more software for those pianos, which included The Old Piano Roll Blues brilliantly interpreted by Cook,

and Music! Music! Music!, another automated instrument piece by Stephen Weiss and Bernie Baum. America was on a (piano) roll again, and a new love affair started with automated music.

|

Imperial Industrial, in conjunction with Hardman, Peck & Company, also got in on the act by developing an even smaller console [some histories have erroneously claimed it was a spinet] player piano that allowed the user to either flip a switch or pull out the pedals and pump, just as they had three decades prior. While it came out in the spring of 1957 after the nostalgia surge had died down, the Hardman DUO (a nod to the older Duo-Art name, whose rolls it could accommodate) nonetheless did fairly well. In their advertising, Hardman and Imperial Industrial aimed at the modern suburban family of the space age, yet called on nostalgia for sales as well:

The DUO is an ideal family piano, one that every member can play even those who have never had a lesson. Lyrics are printed right on the music rolls, so everyone can sing along as well. This adds greatly to the fun of family gatherings and parties. The young student in the family will find he learns faster on the DUO. He can play it manually for practice lessons, and as a player-piano to observe the technique of more advanced arrangements.

Herman had also contributed to an increase in sales from QRS through his Personality Series of rolls. Given Cook's extraordinary ability, and either the cooperation or tolerance of a number of piano artists, the series was comprised of rolls "played as arranged" by well-known artists. This often meant a paraphrase or nearly exact replication of an artists' recording or at least his style for some well-known works. Herman later admitted that the practice may not have been entirely ethical, but the labels were worded in such a way as to be open to interpretation.

The 1950 census taken in Harrison, Westchester County, New York, had shown Max as the president and manufacturer of a curioiusly but accurately described "Perforated Product" company. As the 1960s started, things were looking bright for QRS. Even after Aeolian's secondary reintroduction into the roll market in the 1950s, QRS was still the dominant leader of popular piano rolls, many featuring the latest top forty hits.

While the future of company was fairly secure, Max would not be around to help shape it. Working literally to the end, he died in the Bronx office of Imperial Industrial on October 11, 1961 from heart failure along with diabetic complications. His obituary in the New York Times listed many of the fine clubs that he was a member of, including the Westchester Country Club where he resided, the Metropolitan Club in New York City, the Everglades Club in Palm Beach, Florida, and the Peninsula Club in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He was survived by his brother, his second wife Gertrude, his two adopted children and stepson, and his sisters Louise, Dorothy and Marguerite.

|

Herman continued to run the company under Gertrude's direction, taking care of the front office responsibilities and royalties. Cook ran the rest of the factory, making most of the decisions concerning what songs to arrange and release, but left by late 1961 due to strained relations with Mrs. Kortlander. Around 1967 Gertrude sold the firm to player piano restorer and enthusiast Ramsi Tick, and QRS Music, including all the stock and the machines and its original corporate name, was relocated to Buffalo, New York. Herman followed J. Lawrence Cook to Aeolian on 57th Street in New York City. Both of them eventually became frustrated with the slow and disorganized way in which they felt Aeolian was operating, with no central office or facility, and left the company in the 1970s. He remained in New York until 1984 when he retired back to Michigan, dying in July 1987. Stephen Kortlander never got involved in his dad's business, and died in June 1973 in Santa Monica, California. His mother Jean, Max's first wife, followed in 1975. Their adopted daughter is still assumed to be alive in 2010. Gertrude Kortlander, who had lived off of royalties and the sale of QRS, passed on in Rye, New York on March 11, 1981.

QRS Music is still an independent company, although they have been involved with the Story and Clark Piano Company for over two decades. The famous marking piano that was used by Cook and his peers is now part of the factory tour, which thousands of curious tourists and aficionados take every year. Piano rolls are still selling at a rate of over 200,000 per year, although software-driven music and downloads have clearly overtaken the paper market.

Today the legacy of Max Kortlander and QRS are very much alive, albeit in altered form. The company still makes paper rolls, albeit after a temporary shutdown in late 2009, but concentrate more on digital media. The early performances by Max and his staff can now be played back from MIDI, a special Compact Disc, or even a wireless internet connection on a QRS Pianomation System and PNOScan attached to nearly any piano, and even accompanied by instruments or vocals played through an integrated speaker. But the intent is still the same as the pioneers of the industry, including Max Kortlander and Melville Clark, had hoped for. They wanted to bring well-played music into the average household on a device that allowed for the upgrading of the music simply by obtaining new software, or piano rolls. The piano roll is every bit as digital as MIDI on CD is, and in that regard, QRS Music continues to keep Max's long term goals of musical entertainment in the home both current and exciting.

Some of the information on Kortlander was retrieved from the exceptional Billings Rollography, which includes the first authentic history of QRS. Another very useful source was the 1985 interview of Herman Kortlander by Bill Burkhardt, which can be found in its entirety on the AMICA website at http://www.amica.org/Live/Organization/Honor-Roll/KortlanderHerman.htm.Additional information on Max was presented by author and Michigan historian Lee Barnett, formerly with the Michigan State Archives, in an article published on the remarkable Doctor Jazz site run by Mike Meddings. The rest was researched from music archives, radio archives, newspaper listings and public records by the author. Be sure to visit QRS Music for more information on the company.

Compositions

Compositions