|

Dominic James "Nick" La Rocca (April 11, 1889 to February 22, 1961) Lawrence James "Larry" Shields (September 13, 1893 to November 21, 1953) Henry Walter Ragas (November 2, 1890 to February 18, 1919) | |||

LaRocca and/or Shields Compositions LaRocca and/or Shields Compositions | |||

|

1917

Tiger Rag [1]Tiger Rag (Song) [1,2] Ostrich Walk At the Jass Band Ball Barnyard Blues [A] The Original Dixieland One Step [1,3] Reisenweber Rag [1] 1918

War CloudFidgety Feet [War Cloud retitled] Skeleton Jangle [A] Belgian Doll [A] Look At 'em Doing It! [B] Clarinet Marmalade Blues [B,1] New York [1] Lazy Daddy [1] 1919

Satanic Blues [B,4]Toreador Humoresque 'Lasses Candy: One Step 1920

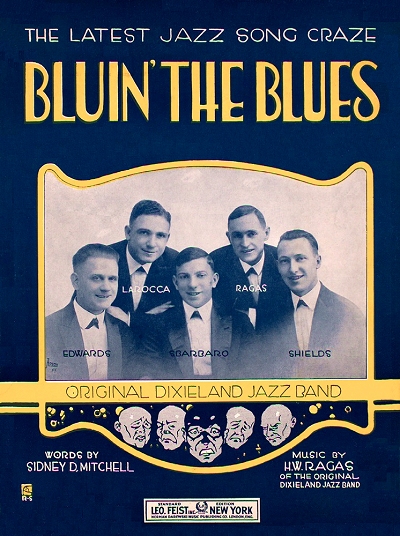

Bluin' the Blues [2]1921

Come To My Arms [A]Ramblin' Blues [5] Some Rainy Night [A,6,7] Once in a While [A,6,7] 1922

Toddlin' Blues1923

The King Tut Strut [A] |

192?

Float Me Down the River to New Orleans [A,9]1936

Old Joe Blade [A]1947

'Lasses Candy [A]1954

Basin Street Stomp * [10]1959

Give Me That Love [A,11]1960

Sweet Lovin' Gal [A,9]Vieux Carre Parade [A,9,12] Sugar Bowl Stomp [A,13]

A. Dominic La Rocca only

B. Larry Shields only 1. by or w/Henry Ragas 2. w/Harry De Costa 3. w/Joe Jordan 4. w/Emile Christian 5. w/Al Bernard 6. w/Carey Morgan 7. w/Mitchell Parish 8. w/Arthur Swanstrom 9. w/Armand Hug 10. w/Carolyn & Ruth La Rocca 11. w/Howard Chandler Franks 12. w/Joseph Mares, Jr. 13. w/Louis Escobedo. * Disputed origin: © 02/24/1954 and renewed in 1982. | ||

Selected Discography Through 1923 Selected Discography Through 1923 | |||

| |||

If there isn't already enough in the way of spurious claims about who invented jazz, trumpeter Nick La Rocca and clarinetist Larry Shields certainly added to the fray with a string of hits that came out almost simultaneously with the newly coined term. And La Rocca's direct claim of the invention of jazz by white people made in his later years was also controversial for its blunt racist overtones.

Dominic [Domenici] James La Rocca (often shown as LaRocca) was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, to Sicilian immigrants Giarolomo "James" La Rocca and Vita "Victoria" De Nina. He was the fourth of six siblings including Rosario (12/1882), Antonia (9/1884), Marie (6/1887), Bartholomew (8/1891) and Leonardo (10/1893). Nick's father was a manufacturer and retailer of shoes, and his older brother had followed suit by the time of the 1900 enumeration. Nick was keen on listening to and participating in one of the many second-line brass bands of New Orleans, but his father discouraged such notions. As a result, he had to learn to play the cornet covertly. As of the 1910 enumeration Victoria had been widowed, but was still running the shoe store. Rosario was listed as a street car conductor, but Nick showed no occupation, even at the age of 21, although he was doing part time work as an electrician when he wasn't moonlighting with local bands. In that regard he was still experimenting with playing music, but not for a living at that point.

Lawrence Shields was born over four years after La Rocca, also in New Orleans, to James Shields, a professional painter, and Emma Puneky Ruth. He had three older siblings by a different father and was the second of four boys from his natural father. The large family included John Ruth (7/1876), Maggie Ruth (2/1879), Mary Ruth (6/1881), James Ruth (10/1884), Patrick (2/1888), Edward (9/1896) and Harris (7/1899). As of the 1910 census Lawrence and some of his brothers are shown as apprentice painters working with their (step)father.

Henry Ragas was one of seven children born in Point A La Hache, Louisiana, to Eusebe Adrian Ragas and Bertha Louisa Masson, the others being William J. (5/5/1884), Eusebe Adrian, Jr. (12/14/1886), Wilfred Masson (12/8/1888), Bertha Louisa (2/2/1893), Ernest Louis (3/14/1897 - Algiers, LA), and Claude James (8/25/1899 - New Orleans, LA). Bertha died in May of 1900, so for the June census, Henry and his siblings were found residing with Eusebe's childless brother Hypolite and his wife Emlie. They may have stayed there for some time until Eusebe could regroup. Hypolite worked as a motorman for the New Orleans trolley system, but it is unclear what Eusebe had done for a living. Henry was difficult to locate in the 1910 census. Growing up, Henry had received adequate training on the piano, and may have been working or on the road performing at that time.

All three boys grew up in an environment in New Orleans that was fostering a unique musical identity for that area, and where before 1900 around which time certain laws were enacted due to the outcome of Plessy vs. Ferguson, the Creole and white musicians had been allowed to perform together. New Orleans was also a busy town in part because of the creation of Sidney Story's cleverly legislated district of 1897 outside of which prostitution was illegal, making it tacitly not unlawful within the boundaries of what became known as Storyville. Even within the distance of a few blocks from one ward to another, the mix of races was evident, and downtown New Orleans was teeming with musical activity, particularly south of Storyville in the Treme and the French Quarter. Even standing outside many of the establishments there, it was not hard to get a basic music education of improvisation and rhythm. So even though music may not have been an established profession for the trio by 1910, it does not mean that they weren't soaking it all in and playing it.

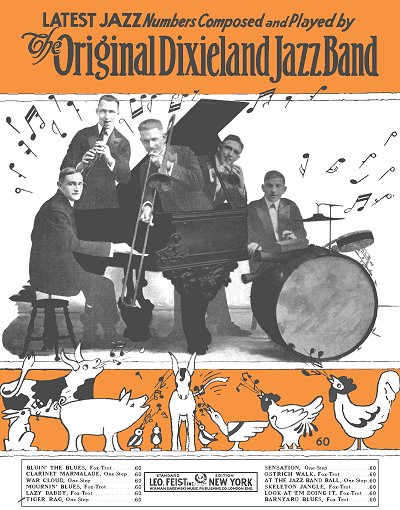

As early as 1914 Nick, Larry and Henry may have been working together in a band that La Rocca had formed from the remnants of Papa Jack Laine's bands in New Orleans, which Nick had been playing with since around 1910. The new group then picked up their cases in 1916 and went up north to Chicago where opportunities to play jazz for real money were increasing weekly. Nick was called in as a replacement for trumpeter Frank Christian at the Booster Club for Stein's Dixie Jass Band under the leadership of drummer Johnny Stein. At the end of their first season, La Rocca had creative or personal conflicts with the group's clarinetist Alcide Nunez. They agreed to a trade with another band, and La Rocca and Stein acquired Shields as a permanent member. By late 1916, some members of the group had departed from Stein's band and moved to New York City where they were now billed as The Original Dixieland Jass Band, "Creators of Jass." The new group was comprised of leader La Rocca on cornet, Shields on clarinet, Ragas at the piano, Eddie Edwards on trombone, and Tony Sbarbaro on the drums.

The new group then picked up their cases in 1916 and went up north to Chicago where opportunities to play jazz for real money were increasing weekly. Nick was called in as a replacement for trumpeter Frank Christian at the Booster Club for Stein's Dixie Jass Band under the leadership of drummer Johnny Stein. At the end of their first season, La Rocca had creative or personal conflicts with the group's clarinetist Alcide Nunez. They agreed to a trade with another band, and La Rocca and Stein acquired Shields as a permanent member. By late 1916, some members of the group had departed from Stein's band and moved to New York City where they were now billed as The Original Dixieland Jass Band, "Creators of Jass." The new group was comprised of leader La Rocca on cornet, Shields on clarinet, Ragas at the piano, Eddie Edwards on trombone, and Tony Sbarbaro on the drums.

The new group then picked up their cases in 1916 and went up north to Chicago where opportunities to play jazz for real money were increasing weekly. Nick was called in as a replacement for trumpeter Frank Christian at the Booster Club for Stein's Dixie Jass Band under the leadership of drummer Johnny Stein. At the end of their first season, La Rocca had creative or personal conflicts with the group's clarinetist Alcide Nunez. They agreed to a trade with another band, and La Rocca and Stein acquired Shields as a permanent member. By late 1916, some members of the group had departed from Stein's band and moved to New York City where they were now billed as The Original Dixieland Jass Band, "Creators of Jass." The new group was comprised of leader La Rocca on cornet, Shields on clarinet, Ragas at the piano, Eddie Edwards on trombone, and Tony Sbarbaro on the drums.

The new group then picked up their cases in 1916 and went up north to Chicago where opportunities to play jazz for real money were increasing weekly. Nick was called in as a replacement for trumpeter Frank Christian at the Booster Club for Stein's Dixie Jass Band under the leadership of drummer Johnny Stein. At the end of their first season, La Rocca had creative or personal conflicts with the group's clarinetist Alcide Nunez. They agreed to a trade with another band, and La Rocca and Stein acquired Shields as a permanent member. By late 1916, some members of the group had departed from Stein's band and moved to New York City where they were now billed as The Original Dixieland Jass Band, "Creators of Jass." The new group was comprised of leader La Rocca on cornet, Shields on clarinet, Ragas at the piano, Eddie Edwards on trombone, and Tony Sbarbaro on the drums.A steady gig was obtained for them by an enthusiastic Al Jolson, one of their early fans, at Reisenweber's Cafe on Columbus Circle in midtown Manhattan. They were known for wild stage antics and general musical unruliness, which made them an instant hit in the jazz deprived city. It didn't hurt that they got press coverage, and LaRocca always had something provocative to say. "Jazz is the assassination of the melody, it's the slaying of syncopation." While playing they would dance, assume awkward positions, or play their instruments in an unusual manner, such trombonist Edwards sliding the trombone with his foot

After a successful start at Reisenweber's, the group secured an opportunity to be the first jazz band to record for Columbia Records in early 1917 While that recording session turned out to be a bust, a subsequent session with Victor Records on February 26, 1917, begat two of their first recorded compositions, the Livery Stable Blues and Dixie Jass Band One Step (later the Original Dixieland Jazz Band One Step). Since La Rocca had used the trio of Joe Jordan's That Teasin' Rag for the trio their one step, he was soon ordered by a court to add Jordan's name to the piece and have the records recalled and relabeled with "Introducing That Teasin' Rag by Joe Jordan." This record was followed by one of their most enduring efforts, the wildly popular Tiger Rag. Both La Rocca and Shields' respective June 1917 draft records show them as an "actor (theatrical)", and Henry's as a "vaudeville actor." La Rocca was now shown as married (to Victoria Eleanore Wattigny on 12/8/1915), as was Henry (to Bertha Hickey in 1914) and while Henry gave a Manhattan address, the other two both appeared to still have been situated in New Orleans based on their addresses. All of them declared that they were employed by Reisenweber's in New York City.

he was soon ordered by a court to add Jordan's name to the piece and have the records recalled and relabeled with "Introducing That Teasin' Rag by Joe Jordan." This record was followed by one of their most enduring efforts, the wildly popular Tiger Rag. Both La Rocca and Shields' respective June 1917 draft records show them as an "actor (theatrical)", and Henry's as a "vaudeville actor." La Rocca was now shown as married (to Victoria Eleanore Wattigny on 12/8/1915), as was Henry (to Bertha Hickey in 1914) and while Henry gave a Manhattan address, the other two both appeared to still have been situated in New Orleans based on their addresses. All of them declared that they were employed by Reisenweber's in New York City.

he was soon ordered by a court to add Jordan's name to the piece and have the records recalled and relabeled with "Introducing That Teasin' Rag by Joe Jordan." This record was followed by one of their most enduring efforts, the wildly popular Tiger Rag. Both La Rocca and Shields' respective June 1917 draft records show them as an "actor (theatrical)", and Henry's as a "vaudeville actor." La Rocca was now shown as married (to Victoria Eleanore Wattigny on 12/8/1915), as was Henry (to Bertha Hickey in 1914) and while Henry gave a Manhattan address, the other two both appeared to still have been situated in New Orleans based on their addresses. All of them declared that they were employed by Reisenweber's in New York City.

he was soon ordered by a court to add Jordan's name to the piece and have the records recalled and relabeled with "Introducing That Teasin' Rag by Joe Jordan." This record was followed by one of their most enduring efforts, the wildly popular Tiger Rag. Both La Rocca and Shields' respective June 1917 draft records show them as an "actor (theatrical)", and Henry's as a "vaudeville actor." La Rocca was now shown as married (to Victoria Eleanore Wattigny on 12/8/1915), as was Henry (to Bertha Hickey in 1914) and while Henry gave a Manhattan address, the other two both appeared to still have been situated in New Orleans based on their addresses. All of them declared that they were employed by Reisenweber's in New York City.The controversy behind the origin of jazz was long spurred on by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band's leader, Nick La Rocca, who blatantly insisted that not only was it he who had coined the name jass/jazz, but that he and his group had all but invented the music as well. He further stated that not only was it a white music form since the negro was not inherently capable of such complex compositions, but that negroes were merely copying the white musicians as they had in so many other musical forms. This arrogant and ignorant statement understandably incensed a large sector of both races of the music community, who rightly considered the O.D.J.B. as "a bunch of white guys playing colored music." Still, their recordings sold well thanks to good distribution and advertising.

Still, their recordings sold well thanks to good distribution and advertising.

Still, their recordings sold well thanks to good distribution and advertising.

Still, their recordings sold well thanks to good distribution and advertising.As for the genre name - jass was a black euphemism long associated with the act of sexual intercourse, and somewhat commonly as the male by-product of the act. Some believe that the word had earlier origins in France, and that the meaning actually translates into "somewhat disorganized" or "loose". The term Jasper, a disparaging name used by field bosses to refer to field hands by other than their name, is also cited as a possible origin. The word "jass" first appeared in late 1916, but quickly was rechristened "jazz" because of problems the band was having with vandals blotting out the "J" on their advertising posters. Early jazz music, now known as traditional jazz, was essentially ragtime music with a section that allowed for improvisation of the solo instruments.

Tiger Rag was little more than themes that La Rocca and Shields, with help from Ragas, allegedly assembled from known French quadrilles that were popular in New Orleans. Authorship of the piece, and many others performed by the ensemble, remains murky as best, with a bevy of other musicians claiming authorship, contributions, or citations of somebody else having composed the work. Some of those names include Buddy Bolden, Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton, Freddie Keppard, Sidney Bechet, and even Joseph "King" Oliver, all of whom likely helped to shape the Tiger Rag in some fashion.

It was the style of playing that set their rendition apart from other music of the time, and made La Rocca and Shields so successful, along with the obvious advantage that they had being white in terms of access to recording studios, performance venues and publishers. Ragas also contributed pieces to the band's repertoire, not always getting due credit, including Tiger Rag. His playing was often lost in the cacophony of the horns in the front line, in part because of the limited recording scope of the acoustic horns used at that time, but also because he was providing the bass line and chords in the absence of a tuba and banjo. In the format that the band used for a typical three minute recording, Henry usually did not take any solos. His contribution to Tiger Rag and other O.D.J.B. pieces, however, may have been very useful in condensing what the band played into a printable format for sheet music, along with arrangers at the publishing office of Leo Feist.

|

The question of ownership of tunes of an improvised nature became an issue for the courts to have to deal with in October 1917, when a dispute between Nunez and La Rocca over authorship of Livery Stable Blues (a.k.a. Barnyard Blues) landed the pair in court. According to the October 27, 1917 issue of The Music Trade Review, "in order to determine whether Dominick La Rocca or Alcide Nunez wrote 'The Livery Stable Blues,' a court in Chicago had a jazz band play the number." La Rocca ultimately carried the day, but the process simply underscored how difficult it was to determine how to set a benchmark beyond the chord structure of a piece rife with improvisational performances in order to establish authorship.

There were many recording sessions that followed the Victor sessions in 1917 and 1918, including some more for Columbia and Aeolian-Vocalion, a number of which were never issued, at least in the United States. Despite their jazz fame, the band was equally well known for their stage performances that featured novelty and comedy numbers. It was on stage that they found success both in the United States and Europe. La Rocca tried to keep their name in the public eye with constant interviews containing even more outrageous claims and phrases. Following their run at Reisenweber's they went a few miles north to the Alamo Cafe on 148th Street, then out to bustling Coney Island at the famous College Inn. Near the end of 1918 trombonist Eddie Edwards left the group and was replaced by Frank Christian's brother, Emile Christian.

Following their run at Reisenweber's they went a few miles north to the Alamo Cafe on 148th Street, then out to bustling Coney Island at the famous College Inn. Near the end of 1918 trombonist Eddie Edwards left the group and was replaced by Frank Christian's brother, Emile Christian.

Following their run at Reisenweber's they went a few miles north to the Alamo Cafe on 148th Street, then out to bustling Coney Island at the famous College Inn. Near the end of 1918 trombonist Eddie Edwards left the group and was replaced by Frank Christian's brother, Emile Christian.

Following their run at Reisenweber's they went a few miles north to the Alamo Cafe on 148th Street, then out to bustling Coney Island at the famous College Inn. Near the end of 1918 trombonist Eddie Edwards left the group and was replaced by Frank Christian's brother, Emile Christian.Despite their success, or perhaps because of it, La Rocca became mildly paranoid about the other similar bands that were popping up all over the country, particularly in New York. Competition from groups such as the hot Coney Island orchestra led by Jimmy Durante created a headache for Nick. He even reportedly offered Frank Christian $200 and a ticket back to New Orleans just to clear the path a little more for his own success. (The offer was refused, of course.) After a battle of the bands between the O.D.J.B. and other groups resulted in a win for a band fronted by Nunez and drummer Joe "Ragbaby" Stevens (possibly Stephens), Ragbaby found that his drumheads had all been slashed following that decision.

As jazz music started to mature into the styles of the roaring twenties, the band became a thing of the past. The first tragedy for the band came in 1919 when Ragas died as a result of the Spanish Flu pandemic, just two weeks after he had applied for a passport so the group could travel to England to perform at the London Hippodrome. He was replaced in short order by J. Russel Robinson, one of several contenders for the spot which included pioneer champion ragtime pianist Mike Bernard. La Rocca retreated with the band to the Hippodrome that March to renewed acclaim, recording several sides for Columbia there in six sessions from April 1919 to May 1920. Likely due to a contract with Victor, none of them were released on the Columbia label in the United States. Of those tracks, their last one, Soudan became a major hit in the UK and Europe. They returned to the U.S. in mid-1920, having missed the 1920 census. Then the group made a few more recordings for Victor before starting out on four years of arduous touring, undergoing personnel changes throughout that time. After a few tumultuous trips, La Rocca had a mental breakdown in 1925 and the original band was finally dissolved.

undergoing personnel changes throughout that time. After a few tumultuous trips, La Rocca had a mental breakdown in 1925 and the original band was finally dissolved.

undergoing personnel changes throughout that time. After a few tumultuous trips, La Rocca had a mental breakdown in 1925 and the original band was finally dissolved.

undergoing personnel changes throughout that time. After a few tumultuous trips, La Rocca had a mental breakdown in 1925 and the original band was finally dissolved.While the other band members went on to continue their careers in jazz performance, replacing Nick with trumpeter Henry Levine, La Rocca ended returning to New Orleans to work as a building contractor. He was shown as residing there the 1930 census with his wife Victoria, and employed as a "house carpenter."

Either LaRocca or Shields reformed the group in the mid-1930s in Chicago (stories vary as to who initiated the move). They played in New York and New Orleans and recorded some more sides for Victor with La Rocca, Shields and Robinson in the lineup, even staging their comeback in a somewhat fictionalized March of Time newsreel in early 1937. In late 1939 Larry tried one more short stint with surviving members and his brother Harry, recording six sides for the secondary Victor label Bluebird Records. The O.D.J.B. was defunct by early 1940. They were probably not helped in that regard by statements that Nick had made in the late 1930s, when his mental state was questionable, that only white people could have invented jazz because Negroes were not capable of that level of original thinking. He further claimed in the 1950s that he should be regarded as "the Christopher Columbus of music," and on one occasion that he was the "most lied about person in history since Jesus Christ," all of which quickly eroded his credibility as a creator of jazz. This was despite the fact that he had clearly highly regarded the band of Joe Oliver while still living in New Orleans in the 1910s.

For the 1940 enumeration Nick and Victoria were back in New Orleans, showing that they had both been living in Manhattan in 1935. Nick was back in the construction business working as a carpenter. Larry and Harry Shields were both located in New Orleans for the 1940 record, living with their widowed mother Emma and sister Margaret. Both were listed as orchestra musicians. Larry retired to California in the early 1940s. The 1950 census taken in Los Angeles showed Larry and his wife Clara working respectively as a menswear salesman in a department store, and a beauty salon operator, with no mention of musical activity. Shields died within a little more than three years later in Los Angeles at age 60. As for Nick, he had been remarried during the 1940s to a woman named Ruth, who was thirty or more years his junior, and who had brought at least one child to their union. The 1950 census indicated that four more children had been born to the couple, including a set of twins named Ruth and Dominick Jr. in 1943. He was still working as a carpenter.

One disputed attribution was the composition of Basin Street Stomp. While it had been known to be one of the early works recorded and allegedly composed by the Basin Street Six in 1951, the piece was officially copyrighted in February 1954 and renewed 28 years after that in 1982, attributed to La Rocca and Howard Chandler Franks. At least one source claimed it to be from as early as 1914, but this seems unlikely. The liner notes for the Circle record claim it was composed by the group, of which bassist "Bunny" Franks was a member. If Howard and Bunny were one and the same is another question altogether, since there was a Harry Elwood Franks born in 1918 who was cited as being nick-named "Bunny" at the time of his death. However, one copyright source shows Bunny to be Howard's alias. It is possible that the misattribution was the fault of either the label or the band members, much in the way many La Rocca and Shields tunes were attributed to the entire ODJB. However, the copyright records stand, so clearly La Rocca deserves credit for this work.

The early performances of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, even though they often sound a bit stilted or stale in comparison to those of King Oliver or Louis Armstrong's groups of that period, still informed and influenced many musicians to follow. Larry's early playing was cited as an inspiration by several swing era players, including Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman. Ragas set some standards for jazz arrangements and laying down a good solid foundation at the piano, even though his career was cut tragically short by a virus. After having submitted copyrights for a few more tunes in the late 1950s and early 1960s, La Rocca died in 1961 in Louisiana just short of age 74, but not before having contributed by way of interview to a book on his band written by H.O. Brunn. In it, he not only derided the ability of the allegedly imitative Negro bands, but claimed to have started his group in 1908, and was unkind to most of his fellow band members as well, save for Shields. To this day, there is little evidence that the O.D.J.B. founders invented jazz per se, but there is more than enough to verify that they contributed greatly to its early and continuing success, and took it from a regional genre to a worldwide sensation. Their legacy was continued into the 21st century by La Rocca's son Jimmy LaRocca with a reincarnation of the O.D.J.B. featuring music composed by both father and son.