|

Leroy Robert (Lee Roy) "Lasses" White (August 28, 1888 to December 16, 1949) | |

Known Compositions Known Compositions | |

|

1912

Nigger Blues [a.k.a. Negro Blues]1914

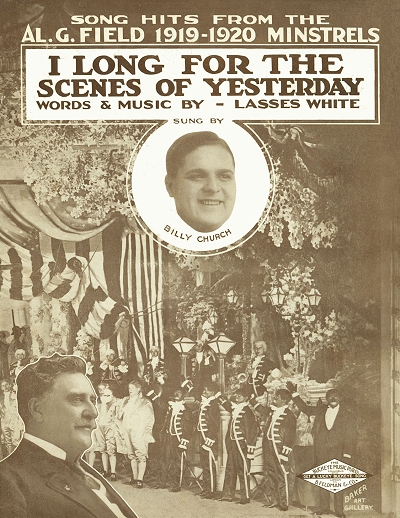

Honey Kiss Your Papa Goodbye1919

I Long for the Scenes of YesterdayIf You Knew What it Meant to be Lonesome 1920

Midnight BluesDancing through Dixieland Sweet Mama Tree Top Tall (Won't You Kindly Turn Your Damper Down) 1923

Mother Mine1924

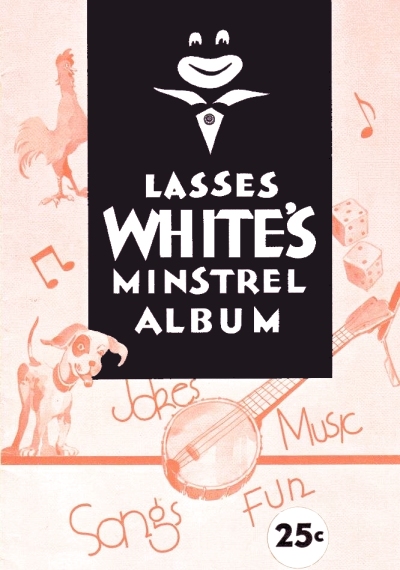

Lasses White Musical Album:You Got to Strut It When You Come Out of Your Two Time Mind Somebody Else 1925

Lasses White All-Star Minstrels Music Album:Happy Sam Please Don't Say Goodbye Don't You "Cadillac" Me |

1935

Lasses White's Book of Humor and Songs:Mother of Home Sweet Home If You Knew What it Meant to be Lonesome In Cumberland Valley (In Tennessee) Taxi Jim One-Eyed Sam. 1942

The Air Corps of Uncle Sam [1]Honest I Do There'll Come a Day Let's Start Life All Over 1945

I've Got Nuggets in My Pockets [2,3]1947

I'm Casting My Lasso Towards the Sky [2]1949

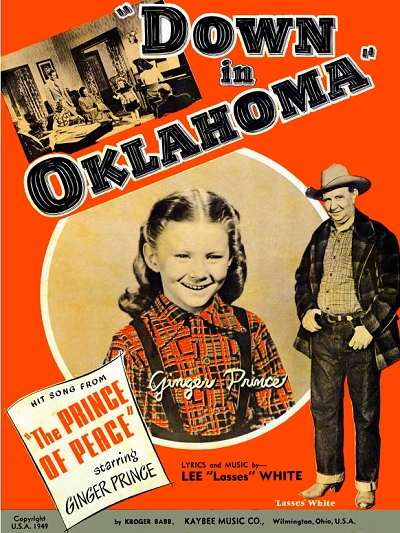

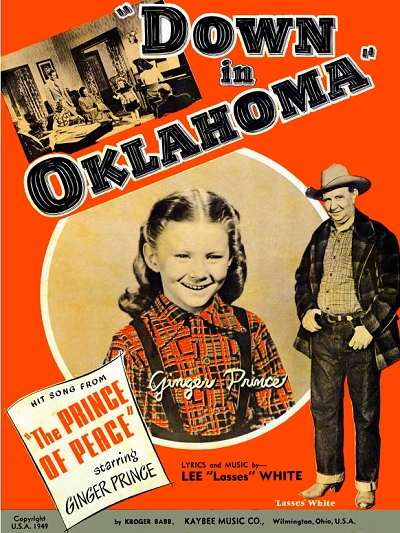

Down in Oklahoma1952 [Posth]

Mine, All Mine

1. w/Lois & Ervin Belmer

2. w/Jimmy Wakely 3. w/Lee White |

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |

|

1922

Old Time Minstrels: Part 1 [1]Old Time Minstrels: Part 2 [1]

1. Lasses White Minstrel Company

|

Matrix and Date

[Columbia 98070] 05/??/1922[Columbia 98071] 05/??/1922 |

While we live in a time where there is a higher awareness of pressing questions of gender identity or even national or regional identity, there were those during the ragtime era and beyond who potentially had their own struggles, or even optimistic aspirations, dealing with race identity. Such may have been the case with Texas native Le Roy "Lasses" White, whose last name gave away his birth race, but his stage persona and appearance for many years suggested otherwise.

His birth name was Leroy Robert White, but he put it through various permutations during his adult life, Leroy, born in Wills Point, Texas, was the youngest child of Texas natives Edmond Charleston White and Panola Martin Hatchett. His older siblings included Anna Mae (9/27/1874), Leta "Lettie" Ann 10/11/1876), Robert Quinn (10/17/1878), William Edmond (9/3/1880), and Edna Earle (9/11/1882). The 1880 census showed Edmond to be a farmer in Cherokee County, Texas. He died at some point during the early-to-mid-1890s, leaving Panola and her children to fend for themselves. The 1900 enumeration found the family living in Dallas, Texas, with Panola and Edna working as seamstresses, Robert as a blacksmith, and William as an apprentice in a machine shop. Leroy was still in school at age 11.

It is not clear what type of music education Leroy received either in the Dallas schools or privately, but he showed a natural talent for entertaining, and was inspired by some of the shows he saw coming through Dallas in the 1900s. Among those that he found a connection with was the soon to be dying institution of minstrelsy, that of white entertainers (sometimes black as well), many in blackface, emulating alleged Negro entertainment with comedy sketches of questionable merit, and a variety of old-time songs. Many, including Leroy (and ultimately nationally famous entertainers Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, considered blackface entertainment to be an homage to the black race. Jolson even commented that it helped to amplify the expression of his mouth and eyes from the seats in the back of the room. It remains controversial a century and more later, but minstrelsy was still a viable competitor to vaudeville and stage musicals as late as the 1910s, albeit on the decline by that time.

Many, including Leroy (and ultimately nationally famous entertainers Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, considered blackface entertainment to be an homage to the black race. Jolson even commented that it helped to amplify the expression of his mouth and eyes from the seats in the back of the room. It remains controversial a century and more later, but minstrelsy was still a viable competitor to vaudeville and stage musicals as late as the 1910s, albeit on the decline by that time.

Many, including Leroy (and ultimately nationally famous entertainers Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, considered blackface entertainment to be an homage to the black race. Jolson even commented that it helped to amplify the expression of his mouth and eyes from the seats in the back of the room. It remains controversial a century and more later, but minstrelsy was still a viable competitor to vaudeville and stage musicals as late as the 1910s, albeit on the decline by that time.

Many, including Leroy (and ultimately nationally famous entertainers Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, considered blackface entertainment to be an homage to the black race. Jolson even commented that it helped to amplify the expression of his mouth and eyes from the seats in the back of the room. It remains controversial a century and more later, but minstrelsy was still a viable competitor to vaudeville and stage musicals as late as the 1910s, albeit on the decline by that time.It appears that Leroy had already set his goal to not only be in but run and star in a minstrel show as he approached adulthood. He had been working as a house painter in Dallas during his late teens. A couple of years after he was out of school, White joined a Texas vaudeville troupe, and was seen in advertisements from 1909 to at least 1911 in a couple of organizations. The 1910 census showed that his mother had remarried to Robert J. Oliphant, 24 years her senior, around 1904. Leroy, the only one of Panola's children still in the home, was listed as an actor in vaudeville. The Dallas city directory for that year pegged him as a "showman." By this time, he was starting to use the quoted name of "Lasses," which he had reportedly acquired as a child from his sweet tooth for molasses candies and similar goodies. He also started altering his first name to LeRoy or Le Roy, depending on who was writing about his act. In 1910, LeRoy was married for the first time, but the name of his wife was not readily located, only mentioned as Mrs. White in a couple of documents.

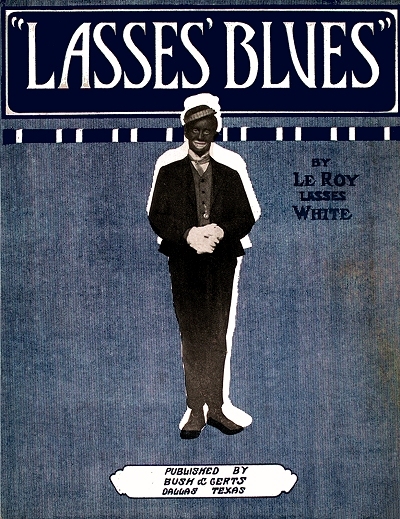

White ironically became famous for being black, starting with his first known song publication. Actually it was more of a rewrite of a collection of known verses and a common blues theme, but it helped to set a standard of sorts for the rompin' stompin' type of blues that became popular on the Southern vaudeville during that time period. Originally copyrighted in 1912 as The Negro Blues, or also simply as The Blues, the original work had as many as fifteen verses in the manuscript, not including the second one found in the printed edition. Either White, or more likely his publisher, Bush and Gerts of Dallas, trimmed the verses to six in 1913, then changed the title to the somewhat more offensive Nigger Blues, a surprising move as by that time most "coon songs" had all but died out in most parts of the country nearly a decade prior, and the term was generally not used in minstrelsy. It was also arguably more of a vaudeville piece than minstrel-like in nature. Still, there is nothing in any of the lyrics that reflects or echoes the questionable title. (The author's good friend and colleague Jeff Barnhart started performing this around 2009 and based on another colleague's suggestion he called it Lasses' Blues after the composer's stage name, as displayed on the tastefully modified sheet music cover.)

this around 2009 and based on another colleague's suggestion he called it Lasses' Blues after the composer's stage name, as displayed on the tastefully modified sheet music cover.)

this around 2009 and based on another colleague's suggestion he called it Lasses' Blues after the composer's stage name, as displayed on the tastefully modified sheet music cover.)

this around 2009 and based on another colleague's suggestion he called it Lasses' Blues after the composer's stage name, as displayed on the tastefully modified sheet music cover.)Around the same time as his blues was gaining traction, LeRoy was featured as Henry in the Bud and Henry vaudeville pseudo-minstrel musical company he had formed with partner Frank Hughes, playing the part of Bud. It had played continuously in Dallas through most of 1912 and into 1913 before going on the road. By that time, White was his troupes featured entertainer outside of their musical comedy one-act, Get Rich Quick, and got well-reviewed as a reliable "laugh producer" in most cities throughout the West and Midwest. After having dabbled with running his own organization, LeRoy was asked to join one of the largest and most famous minstrel troupes touring the country, that of George "Honey Boy" Evans. He was one of the top featured comic singers in a company of sixty or entertainers touring the country from 1914 into 1915, and became the Welsh entertainer's primary understudy. Included in his act was another song from his own hand, Honey Kiss Your Papa Goodbye.

Unfortunately, stomach cancer took Evans on March 5, 1915 in Baltimore, Maryland. However, in the true spirit of the business, "the show must go on," and it did just that in Anderson, South Carolina, a mere four days after his death. The Anderson Daily Intelligencer of March 10, 1915, singled out White in his role with the company:

Last night's show brought to the front LeRoy "Lasses" White, former understudy of the late leader of the minstrels. It is no light burden that has fallen upon this comedian's shoulders—that of making the "Honey Boy Minstrels" a go without the presence of George Evans. Newspaper criticisms had heralded him as a worthy successor to the real "Honey Boy," and a minstrel altogether as pleasing to audiences generally as the star into whose place he has stepped. It would be hard to convince the audience who saw him last night that George Evans was any better.

As may be expected without Evans in the mix, LeRoy eventually reshaped the company into his own show, albeit in a much reduced size, taking it down to a dozen or so on the stage by 1916. Focusing a little less on the minstrelsy part, Lasses White and his Southern Sunflowers toured many of the mid-sized theaters of the Midwest and South throughout 1916, often competing with short films being shown in the same venues. By late in the year he was working with Neil O'Brien's Minstrels, playing somewhat larger theaters along the East Coast. He then migrated to Al G. Field's Greater Minstrels in early 1917, which was run by entertainer Alfred Griffin Hatfield. His May 25, 1917, draft record, taken in Dallas, had him working for manager Morris Frankel at the Majestic Theater in Birmingham, Alabama. He also referenced his wife on the record. She most likely had accompanied him on some of his tours, as they had apparently not established a solid home base in Dallas.

By late in the year he was working with Neil O'Brien's Minstrels, playing somewhat larger theaters along the East Coast. He then migrated to Al G. Field's Greater Minstrels in early 1917, which was run by entertainer Alfred Griffin Hatfield. His May 25, 1917, draft record, taken in Dallas, had him working for manager Morris Frankel at the Majestic Theater in Birmingham, Alabama. He also referenced his wife on the record. She most likely had accompanied him on some of his tours, as they had apparently not established a solid home base in Dallas.

By late in the year he was working with Neil O'Brien's Minstrels, playing somewhat larger theaters along the East Coast. He then migrated to Al G. Field's Greater Minstrels in early 1917, which was run by entertainer Alfred Griffin Hatfield. His May 25, 1917, draft record, taken in Dallas, had him working for manager Morris Frankel at the Majestic Theater in Birmingham, Alabama. He also referenced his wife on the record. She most likely had accompanied him on some of his tours, as they had apparently not established a solid home base in Dallas.

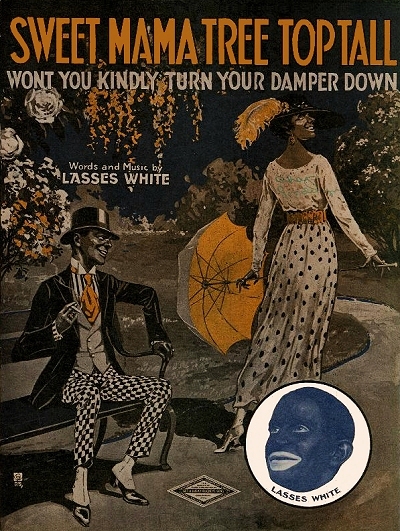

By late in the year he was working with Neil O'Brien's Minstrels, playing somewhat larger theaters along the East Coast. He then migrated to Al G. Field's Greater Minstrels in early 1917, which was run by entertainer Alfred Griffin Hatfield. His May 25, 1917, draft record, taken in Dallas, had him working for manager Morris Frankel at the Majestic Theater in Birmingham, Alabama. He also referenced his wife on the record. She most likely had accompanied him on some of his tours, as they had apparently not established a solid home base in Dallas.After World War I concluded, there was a change of climate across the country concerning entertainment, much of it leaning more towards more genteel forms that were not the staple of minstrelsy, and with increasing competition from studio films. During his stint with Field's Minstrels from 1917 into mid-1920, he established a regular residence in Dallas. It is unclear why the 1919 city directory listed LeRoy as a salesman in an unspecified industry, but it was likely a temporary off-season position at best. In 1920 he was shown as an actor again, having renewed his association with Field, and touring the Midwest. Having not been readily located in the January, 1920, enumeration, LeRoy was probably on the road once again with the Field troupe. He may also have been divorced by this time or soon afterward. White had also copyrighted several songs during 1919 and 1920 that seemed suited for either vaudeville or minstrel shows, including the sassy and highly suggestive Sweet Mama Tree Top Tall (Won't You Kindly Turn Your Damper Down), which was soon recorded by other artists, and the characteristic regional number, Dancing through Dixieland.

Lasses left the Field organization and struck out on his own in mid-1920, forming the "Lasses" White All Star Minstrels, a group of around fifty performers that he would head for several years. That he was already a known quantity in entertainment was made clear in advance of one of their debut performances, noted in the August 17, 1920 edition of the Maysville, Kentucky, public ledger:

The newest big minstrel organization to seek a place in the sun is the "Lasses" White All Star Minstrels, headed by the inimitable "Lasses" himself, and embracing in its roster some of the best known names in "corkdom" [referring to the burnt cork used to apply the blackface makeup]. … indications are that the new black face company will prove to be as popular as the older and long established ones like Fields [sic] and O'Brien.

White himself has been before the public as a delineator of negro [sic] character and his status as a blackface comedian has been long established… Now he comes at the head of his own organization and even his rivals admit that Leroy "Lasses" White has gathered about him an organization of superlative brilliance and merit.

In a follow-up article, the same paper noted that "… White in his stage work has faithfully copied the real Southern negro [sic] and it may be said that he comes nearer to being the real thing than do any of his minstrel competitors." In historical retrospect, this may be viewed as a dubious honor at best, but during that period it was considered high praise, and business as usual. In spite of the reports of the decline of minstrelsy, White and his troupe seemed to thrive over the next few years as they toured the country, largely the eastern half. There were some expected shifts in personnel, but the level of entertainment was consistent. Claims that White had written and produced all of the songs in his show were a bit inflated, as some of the numbers were by other composers, and even troupe members. However, he was responsible for much of the content, of which a great deal was neither copyrighted nor published. For the 1924 to 1926 seasons there was even a competitive and mildly successful race horse named Lasses White after him, but it appears to have not been owned by LeRoy. One other success from 1924 was his second marriage, this time to Norma Quigley Parker, whom he would remain with for the rest of his life.

In spite of the reports of the decline of minstrelsy, White and his troupe seemed to thrive over the next few years as they toured the country, largely the eastern half. There were some expected shifts in personnel, but the level of entertainment was consistent. Claims that White had written and produced all of the songs in his show were a bit inflated, as some of the numbers were by other composers, and even troupe members. However, he was responsible for much of the content, of which a great deal was neither copyrighted nor published. For the 1924 to 1926 seasons there was even a competitive and mildly successful race horse named Lasses White after him, but it appears to have not been owned by LeRoy. One other success from 1924 was his second marriage, this time to Norma Quigley Parker, whom he would remain with for the rest of his life.

In spite of the reports of the decline of minstrelsy, White and his troupe seemed to thrive over the next few years as they toured the country, largely the eastern half. There were some expected shifts in personnel, but the level of entertainment was consistent. Claims that White had written and produced all of the songs in his show were a bit inflated, as some of the numbers were by other composers, and even troupe members. However, he was responsible for much of the content, of which a great deal was neither copyrighted nor published. For the 1924 to 1926 seasons there was even a competitive and mildly successful race horse named Lasses White after him, but it appears to have not been owned by LeRoy. One other success from 1924 was his second marriage, this time to Norma Quigley Parker, whom he would remain with for the rest of his life.

In spite of the reports of the decline of minstrelsy, White and his troupe seemed to thrive over the next few years as they toured the country, largely the eastern half. There were some expected shifts in personnel, but the level of entertainment was consistent. Claims that White had written and produced all of the songs in his show were a bit inflated, as some of the numbers were by other composers, and even troupe members. However, he was responsible for much of the content, of which a great deal was neither copyrighted nor published. For the 1924 to 1926 seasons there was even a competitive and mildly successful race horse named Lasses White after him, but it appears to have not been owned by LeRoy. One other success from 1924 was his second marriage, this time to Norma Quigley Parker, whom he would remain with for the rest of his life.The earlier popularity of White's Minstrels and their music prompted LeRoy to put out at least two different folios of their material, both songs and comedy, in the mid-1920s, followed by mild variations in later editions. However, notices of his troupe's performances appeared to wane around the same time, as minstrelsy's second wind appeared to have subsided. He took on another associate around 1926 in the person of Lee David Wilds, whom LeRoy reportedly named "Honey Wilds." But for the most part, it was Lasses who usually took center stage, and got the laughs, as well as the consistent mentions in the press. At the cusp of the coming of sound films, which put vaudeville on notice after having filmed many acts for early sound shorts, it was noted that Lasses more or less had the minstrelsy field pretty much to himself, which made his act both unique and endangered. It was inevitable that in 1929, with the onset of film musicals and the Great Depression almost all at once, that he would perform his last somewhat meager and truncated season on the road before returning to Dallas and Norma. They appeared in Dallas for the 1930 census hosting two boarders in their home.

Texas was among the places particularly hard hit by the Great Depression, a situation exacerbated in the early-to-mid-1930s by the so-called "dust bowl," which created agricultural calamity throughout Northern Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. This left many without money for entertainment, and many more fleeing west to California and Nevada. Even though LeRoy was listed in Dallas city directories as an actor, the lack of newspaper notices for him make it difficult to find much of a career during this challenging time. He managed to produce another folio of his work in 1935, enjoyed a few guest spots as a headliner in old time variety shows, and even was heard on some regional radio stations now and then. However, his career as a blackface performer was all but over. Still, LeRoy had ambition and optimistic Texas-born gumption, and in 1937 he decided to join the institution that had largely helped to quash his prior career.

The Whites turned to the West and arrived in California, where he set out for a career in cinema. Over the next three years this effort yielded him only two known screen appearances in a couple of B-westerns. In the interim, LeRoy reunited with briefly with Lee "Honey" Wilds for appearances on the NBC radio network, reviving some of their old act with new humor infused, and broadcast from WEAF in New York City. By 1940, however, with the rise in popularity of Westerns and period pieces requiring eccentric characters, White turned out to be a reliable character actor, and was steadily employed. The 1940 enumeration affirmed that he was a motion picture actor. Along with the cowboy films and Southern set pieces, he made a brief appearance in the 1944 film Minstrel Man, starring veteran stage actor Benny Fields, who would have his own flirtation with nostalgic vaudeville and latent minstrelsy on vinyl records into the late 1950s. In some of the musical cowboy films LeRoy, who was now often billed as Lee Roy White, even brought in his own songs. Among these moderate successes were Down in Oklahoma and I'm Casting My Lasso Towards the Sky, the latter a yodeling type of cowboy number written with his frequent film costar, Jimmy Wakely. It would soon be recorded by singer Slim Whitman. His take would in turn be revived a half century later as part of the soundtrack of the 1996 science-fiction comedy Mars Attacks, directed by Tim Burton.

In the interim, LeRoy reunited with briefly with Lee "Honey" Wilds for appearances on the NBC radio network, reviving some of their old act with new humor infused, and broadcast from WEAF in New York City. By 1940, however, with the rise in popularity of Westerns and period pieces requiring eccentric characters, White turned out to be a reliable character actor, and was steadily employed. The 1940 enumeration affirmed that he was a motion picture actor. Along with the cowboy films and Southern set pieces, he made a brief appearance in the 1944 film Minstrel Man, starring veteran stage actor Benny Fields, who would have his own flirtation with nostalgic vaudeville and latent minstrelsy on vinyl records into the late 1950s. In some of the musical cowboy films LeRoy, who was now often billed as Lee Roy White, even brought in his own songs. Among these moderate successes were Down in Oklahoma and I'm Casting My Lasso Towards the Sky, the latter a yodeling type of cowboy number written with his frequent film costar, Jimmy Wakely. It would soon be recorded by singer Slim Whitman. His take would in turn be revived a half century later as part of the soundtrack of the 1996 science-fiction comedy Mars Attacks, directed by Tim Burton.

In the interim, LeRoy reunited with briefly with Lee "Honey" Wilds for appearances on the NBC radio network, reviving some of their old act with new humor infused, and broadcast from WEAF in New York City. By 1940, however, with the rise in popularity of Westerns and period pieces requiring eccentric characters, White turned out to be a reliable character actor, and was steadily employed. The 1940 enumeration affirmed that he was a motion picture actor. Along with the cowboy films and Southern set pieces, he made a brief appearance in the 1944 film Minstrel Man, starring veteran stage actor Benny Fields, who would have his own flirtation with nostalgic vaudeville and latent minstrelsy on vinyl records into the late 1950s. In some of the musical cowboy films LeRoy, who was now often billed as Lee Roy White, even brought in his own songs. Among these moderate successes were Down in Oklahoma and I'm Casting My Lasso Towards the Sky, the latter a yodeling type of cowboy number written with his frequent film costar, Jimmy Wakely. It would soon be recorded by singer Slim Whitman. His take would in turn be revived a half century later as part of the soundtrack of the 1996 science-fiction comedy Mars Attacks, directed by Tim Burton.

In the interim, LeRoy reunited with briefly with Lee "Honey" Wilds for appearances on the NBC radio network, reviving some of their old act with new humor infused, and broadcast from WEAF in New York City. By 1940, however, with the rise in popularity of Westerns and period pieces requiring eccentric characters, White turned out to be a reliable character actor, and was steadily employed. The 1940 enumeration affirmed that he was a motion picture actor. Along with the cowboy films and Southern set pieces, he made a brief appearance in the 1944 film Minstrel Man, starring veteran stage actor Benny Fields, who would have his own flirtation with nostalgic vaudeville and latent minstrelsy on vinyl records into the late 1950s. In some of the musical cowboy films LeRoy, who was now often billed as Lee Roy White, even brought in his own songs. Among these moderate successes were Down in Oklahoma and I'm Casting My Lasso Towards the Sky, the latter a yodeling type of cowboy number written with his frequent film costar, Jimmy Wakely. It would soon be recorded by singer Slim Whitman. His take would in turn be revived a half century later as part of the soundtrack of the 1996 science-fiction comedy Mars Attacks, directed by Tim Burton.LeRoy "Lasses" White seemed to thoroughly enjoy his multi-faceted career in show business, both as a star and as a sidekick. His joy came through even during his briefest of roles on screen, which amounted to some 70 films from 1937 to 1950. Among Lee's more celebrated films were Saddle Serenade, West of the Alamo, Song of the Sierras and Mississippi Rhythm, the latter from 1949. He literally acted to his last day, dying during or shortly after the filming of The Texan Meets Calamity Jane in late 1949, having only recently reached age 61. Four of his final films were released after his death. While his overall impact on music, dating back to ragtime, was nominal at best, his joy for keeping alive parts of history that arguably needed to be put to rest, and some that also showed that there was some good history to be revived, was enough to make this son of Texas more than just a footnote among songwriters and performers, as well as a substantive consummate entertainer.

The sources for this biography were culled from copyright records, government sources, and countless newspapers from the 1910s to 1990s. The author would like to note that disregarding or downplaying the use of "Nigger" in a title, and ignoring White's sway as a blackface entertainer in the questionable genre of minstrelsy, would be tantamount to ignoring our history. It is brought out as fact only, and as part of the narrative. We need to keep in mind that this was part of American (and some world) culture that we have hopefully evolved beyond in this century, but that no particular endorsement nor any malice is intended by including it in this story.