Mary Elizabeth "Mae" Brown (May 30, 1884 to March 2, 1934) |

Known Composition Known Composition |

|

c.1913

Highbrow Rag: Syncopated Operatic Melodies |

Mary E. Brown was a role model for women composers and performers, holding a very important role in rolls, piano rolls, with one of the larger companies. While not a prolific composer in any way, her arrangements of piano rags and popular songs into the 1920s, accompanied by her adept interpretations of classical works, have made her one of the more popular names attached to collectible rolls. Yet little is known of her personal life, as it seems to have been her professional life as well.

Mary was born to bookkeeper Samuel A. Brown and his wife Mary A. Burke in Chicago, Illinois. She had four siblings, Thomas A. (9/1885), Eleanor Veronica (8/24/1887), Samuel J. (3/26/1890-3/27/1890) and Florence I. (9/27/1891). For the 1900 enumeration the family was shown living in Chicago with four boarders in the home, and the children all attending school.

Starting around 1902 she attended the Chicago Musical College, and either concurrently or upon graduation took advanced music courses at the St. Xavier Academy. Later in the decade she was hired to teach piano at the academy for two years, and started making a reputation as a capable church organist and performing pianist as well. Mary even played violin and cello in a Chicago area orchestra.

|

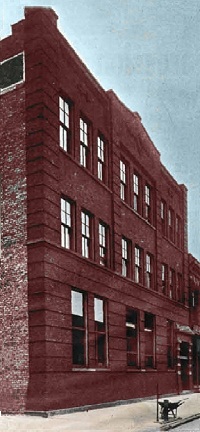

In 1909 at age 25, Mary was hired by the U.S. Music Company, a prominent Chicago area piano roll producer, as an arranger. Over the next few years, until the advent of "hand-played" piano rolls, Mary proved herself as a very capable roll arranger. This process involved the reinterpretation of printed sheet music into holes in the paper roll that sounded like a performance by one or even two skilled pianists, not just a direct translation of the score. In the 1910 census she was shown to still be living with her retired parents in Chicago. Mary was listed as a musician for a music company, her younger sister Eleanor showing the same vocation. Whether Eleanor was also working for U.S. Music is unclear, but it is possible.

Many of Brown's early popular rolls were released under the gender-neutral attribution of Arranged by M.E. Brown. In the early teens as she became one of the lead arrangers for the company, some rolls and even publicity for them would appear with the name Mae Brown, a concatenation of MAry and E. The creation of manually scoring piano roll arrangements was labor intensive and somewhat tedious, so many arrangers only worked a few hours a day or more hours and fewer days, keeping up with their musical activities outside of the piano roll firms. Mary also did so, playing piano or strings with a couple of Chicago orchestras, and working as an organist at "one of the most prominent churches in Chicago," in addition to directing the choir.

Within one to three years (although not likely when she started in 1909 as a later article stated), Mary was made the lead arranger, then the manager of the arranging department for the U.S. Music 88 Note line, and one of the cultivators of talent, bringing other musicians into the firm as needed to cover different performance styles. She had also invested in the company, becoming one of the larger stockholders. By the time of the January, 1920 census she was living with her widowed mother in Chicago, and listed as a musician with U.S. Music Co.

The advent of jazz in the late 1910s combined with improvements in recording markup pianos made it possible for star performers to cut rolls. The fastest growing roll company was QRS Music, who by 1920 had moved from Chicago to New York City to be closer to the major publishers. They were the toughest company to compete against in the 1920s, and would eventually be one of the only ones to survive into and beyond the Great Depression, although not without a lot of internal strife. The other biggest competitor to U.S. Music was Imperial, a label featuring some of the early players of novelty piano, such as Roy Bargy and Charley Straight.

U.S. Music was known more for their arrangements than their stars, although they did acquire a markup piano in mid 1910s that allowed for "live" performances. Mary E. Brown had some star power among buyers of rolls, particularly in Chicago, owing to her sometimes spectacular arrangements. Among them were her medleys, of which her only attributed composition is included. Highbrow Rag [U.S. Music 6486] is a collection of syncopated strains from fairly well known operas, assembled somewhat in the manner that composer Julius Lenzberg did with his rags, but as a performance rather than as sheet music. Mary also assembled a couple of "States Rag" medleys, of which States Rag Medley #8 [U.S. Music 65679F] is the best known. Performer and historian Dick Zimmerman, in his Ragtime Review of September 1973, noted that "She truly made each medley sound like one composition, not just a bunch of tunes tacked together."

Zimmerman had also reprinted an article from an earlier edition of Ragtime Review from 1962 that was very kind to the U.S. Music rolls arranged or "played by" Brown, although there was one glaring but forgivable oversight by the article's author, Russ Cassidy. He claimed that "Nothing is known of Mr. Brown, except that... he had a genius for syncopation and for what might be called melodic line in his fill-ins." Much of the relevant information on Mary, including her gender, had evidently been buried by the decades that had passed after her retirement, since in the 1920s it was a fairly well known fact in the industry that M.E. Brown was actually a female performer. She was also featured in an article in the April 30, 1921 edition of the Music Trade Review:

A WOMAN MUSIC ROLL ARRANGER

Some Interesting Facts Concerning "M. E. Brown," Famous Chicago Music Roll Arranger, and Her Work With U. S. Music Co.

Some Interesting Facts Concerning "M. E. Brown," Famous Chicago Music Roll Arranger, and Her Work With U. S. Music Co.

The majority of piano dealers and merchants who have been selling U. S. music rolls for years are still unaware that the sentence, "Arranged by M. E. Brown," which has appeared on so very many of these rolls, refers to a woman. Such is the fact, however, and she is a very capable and efficient woman, too. So far as is known, she is the only woman who has ever been in entire charge of an arranging department of a large player roll company, besides having considerable financial interest.

Her association with the U. S. Music Co. dates almost from the beginning of the business, seventeen years ago. Miss Brown is particularly well equipped for the work. She is a college woman, a trained musician, a fine pipe organist, a concert pianist and has even played both the violin and the 'cello in the orchestra. While a woman of classical education, Miss Brown has always believed that the public should be given what it wants, and her aim has ever been to refine popular music, and by her skill as an arranger to present it in the most simple and melodious forms. Her effort has been to see that the counter-melodies and harmonies introduced in a piece should all trend towards the central theme, rather to accentuate, but not to obscure it. She objects to the term "jazz" as applied to musical effects, and in her marimba rolls endeavors to reproduce the delicate and dainty tremolo repetition of the violin.

Miss Brown is particularly well equipped for the work. She is a college woman, a trained musician, a fine pipe organist, a concert pianist and has even played both the violin and the 'cello in the orchestra. While a woman of classical education, Miss Brown has always believed that the public should be given what it wants, and her aim has ever been to refine popular music, and by her skill as an arranger to present it in the most simple and melodious forms. Her effort has been to see that the counter-melodies and harmonies introduced in a piece should all trend towards the central theme, rather to accentuate, but not to obscure it. She objects to the term "jazz" as applied to musical effects, and in her marimba rolls endeavors to reproduce the delicate and dainty tremolo repetition of the violin.

Miss Brown is particularly well equipped for the work. She is a college woman, a trained musician, a fine pipe organist, a concert pianist and has even played both the violin and the 'cello in the orchestra. While a woman of classical education, Miss Brown has always believed that the public should be given what it wants, and her aim has ever been to refine popular music, and by her skill as an arranger to present it in the most simple and melodious forms. Her effort has been to see that the counter-melodies and harmonies introduced in a piece should all trend towards the central theme, rather to accentuate, but not to obscure it. She objects to the term "jazz" as applied to musical effects, and in her marimba rolls endeavors to reproduce the delicate and dainty tremolo repetition of the violin.

Miss Brown is particularly well equipped for the work. She is a college woman, a trained musician, a fine pipe organist, a concert pianist and has even played both the violin and the 'cello in the orchestra. While a woman of classical education, Miss Brown has always believed that the public should be given what it wants, and her aim has ever been to refine popular music, and by her skill as an arranger to present it in the most simple and melodious forms. Her effort has been to see that the counter-melodies and harmonies introduced in a piece should all trend towards the central theme, rather to accentuate, but not to obscure it. She objects to the term "jazz" as applied to musical effects, and in her marimba rolls endeavors to reproduce the delicate and dainty tremolo repetition of the violin.One of the most remarkable examples of Miss Brown's arrangements is "Suwanee," [the spelling of the river is nearly correct, but the song was actually "Swanee"] the big Al Jolson hit. In handling this word roll she introduces delicate counter-melodies embodying the theme of Dvorak's "Humoresque" and Liszt's "Hungarian Rhapsody, No. 2." They were worked in so cleverly and unobtrusively that they did not interfere in the least with the singing of the roll, but simply furnished a dainty arabesque accompaniment to the melody of the song itself.

Miss Brown does a great deal of recording herself and subjects her work to the same continual and painstaking revision that she gives the work of others. Few realize how imperfect a roll is when it first comes from the reproducing machine. It has to be marked up, replayed sometimes, a number of times corrected, expurgated and harmonized. "Sometimes, after long experimentation," Miss Brown remarked, "I find it impossible at first to get a roll to suit me. I get so worried over it that I let it lie for a day or so until I get a new vision and can tackle the task of getting it into thorough musical shape from a different viewpoint."

Miss Brown has done a great deal of pioneer work in the music roll field. She laid out the tracker bars for some of the largest orchestrions and electric pianos, and at one time supervised the making of rolls for twenty-four different automatic instruments in addition to turning out over one hundred U. S. player rolls a month.

Some idea of the immense amount of work this remarkable woman has accomplished can be gained from the fact that there is not a single roll issued by the company that does not receive her immediate personal attention and revision and is given her final inspection before the master roll goes to the perforating machine. She is an excellent executive and handles the considerable force under her in a thoroughly tactful manner. She has the prime requisite of being able to impart her enthusiasm to others.

By all appearances, Mary's work was her life, and she apparently never married. She did not take her role at U.S. Music lightly by any means, and was aware that she was the only woman holding such a position in the entire industry. U.S. Music faced increasing competition as QRS started to buy up failing firms, but they still launched a second label of Auto Art rolls in the early 1920s and continued to add to their overall catalog, trying to beat the other companies to the punch when arranging and releasing the latest popular songs. Chicago firms were finding this to be an increasing difficulty as the majority of the publishers released their songs in New York City before distribution to the rest of the country. U.S. Music still worked on their publicity in order to keep sales alive, which included a story on most of the personnel of the company that appeared concurrently in the Music Trade Review and Presto Magazine, the former which is quoted here:

The large catalog of U.S. rolls, the recent addition of the Auto Art roll and the diversity of interpretation have only been possible with the recording personnel, which has at its head Mary E. Brown, the only woman who holds such a position.

Miss Brown is a rare combination of artist and business woman... Her musical work has given her valuable experience. In this capacity her main work consists of locating suitable artists and developing them so that they can conform with the requirements of the organization. Her knowledge of musical composition and arrangement also adds to the value of her work for this department.

In 1926 U.S. Music went the way of many other piano roll companies during the rise of radio and records and the decline of the player piano, and their inventory and masters were sold to QRS in New York. Mary remained in Chicago as a pianist and organist, and evidently arranged a few rolls for the rival Capitol Roll Company of that city, as found in a few listings in Presto and the Music Trade Review of around 1927 and 1928.

As of the 1930 census Mary was living in Maywood, a western suburb of Chicago, in a home with her brother Thomas, nephew William Hagle (the son of her sister Eleanor), and cousin Florence Gibbons. She was working as a theater musician and organist, although that trade was also quickly dying out thanks to the rapidly spreading success of sound films and the deepening Great Depression. Then nothing more was heard of her. Mary E. Brown passed on of an indeterminate cause in 1934 just two months short of her fiftieth birthday.

Some of the basic information on Brown was first uncovered by Richard Zimmerman and Mike Montgomery in the 1970s, with a follow-up by Nora Hulse and Nan Bostick in the early 2000s. The majority of what is presented here was researched by the author in public records, periodicals, newspapers, roll catalogs and other period sources.