Mose Gumble was born in North Vernon, Indiana (even though he or his sister later inexplicably claimed Ohio) a few years before his songwriting brother Albert. The family of German immigrant Isaac Gumble and his French wife Rachel Baum included Moses, Lillian (7/1878), Albert (9/1881) and Walter (1/1883). Isaac owned a retail drug store in North Vernon, and the family was fairly well off as they also list a domestic in the house, Annie Shulpert. The 1920 census suggested an 1879 birth date for Moses, but the 1880 and 1900 census are both clear on 1876 being the correct year, so that was likely an error of vanity common among musicians of that era.

Not much is known of Moses' early years in Indiana and Cincinnati, Ohio, where the family moved in the 1890s. His father died in the mid-1890s leaving Rachel as a widow. Albert and Mose both received some music education at the Auditorium School of Music with Herman Froehlich (nothing definitive found on Mr. Froehlich). Mose, like his younger brother Albert, may have been a student of Clarence Adler of Cincinnati, who also taught famed composers like Aaron Copland and Richard Rodgers, but the association between Mose and Adler is hard to confirm, even though he was attending the same school that Mr. Adler was teaching at. In 1897 while still in college, Moses had his first known publication issued, King of the Sporty Boys. The follow up piece, so rare it was virtually unknown until uncovered in 2013, was his Young Men's Business Club March. Both were issued by George B. Jennings of Cincinnati. As of the 1900 census, the four siblings were still living in Cincinnati with Rachel. The oldest, Moses, did not list an occupation, and Albert and Walter were still listed as in school.

In an 1899 article in the Yale Literary Magazine about Gumble in the mid-1890s, Mose was lauded for his amazing interpretations of the new music, ragtime.  It noted how he would usually appear after ten o'clock, a time after the proper and genteel people would have left the club-house at the college in Cincinnati where he was often heard. He was evidently reluctant to get started, but once at the piano would take over the room. "Mose could no more have kept away from a piano than a rabbit from a cabbage patch." The author called Gumble's repertoire "voluminous and vast," stating he seemed to know every "coon" song under the sun, and even noting that Mose played one or two of his own compositions, although none had been in print to that time. One incident was cited in which Professor Pützenjammer, a distinguished piano teacher, walked in one evening to play a few selections. Among them was Simple Aveu which was delicately rendered in a fine fashion. Mose walked in around this time, and after the professor left the bench, he sat down, fooled around for a moment, and then launched into a ragtime version of the same piece. The article's author called on a number of wild superlatives to describe the bombastic performance. In spite of the tumultuous applause, it evidently left Herr Pützenjammer enraged, and he shouted at the crowd of ignorant "dumkopfs" as he exited the room. In general, Mose was known to be one of the most genial of people with a wonderful voice and affable sense of humor.

It noted how he would usually appear after ten o'clock, a time after the proper and genteel people would have left the club-house at the college in Cincinnati where he was often heard. He was evidently reluctant to get started, but once at the piano would take over the room. "Mose could no more have kept away from a piano than a rabbit from a cabbage patch." The author called Gumble's repertoire "voluminous and vast," stating he seemed to know every "coon" song under the sun, and even noting that Mose played one or two of his own compositions, although none had been in print to that time. One incident was cited in which Professor Pützenjammer, a distinguished piano teacher, walked in one evening to play a few selections. Among them was Simple Aveu which was delicately rendered in a fine fashion. Mose walked in around this time, and after the professor left the bench, he sat down, fooled around for a moment, and then launched into a ragtime version of the same piece. The article's author called on a number of wild superlatives to describe the bombastic performance. In spite of the tumultuous applause, it evidently left Herr Pützenjammer enraged, and he shouted at the crowd of ignorant "dumkopfs" as he exited the room. In general, Mose was known to be one of the most genial of people with a wonderful voice and affable sense of humor.

It noted how he would usually appear after ten o'clock, a time after the proper and genteel people would have left the club-house at the college in Cincinnati where he was often heard. He was evidently reluctant to get started, but once at the piano would take over the room. "Mose could no more have kept away from a piano than a rabbit from a cabbage patch." The author called Gumble's repertoire "voluminous and vast," stating he seemed to know every "coon" song under the sun, and even noting that Mose played one or two of his own compositions, although none had been in print to that time. One incident was cited in which Professor Pützenjammer, a distinguished piano teacher, walked in one evening to play a few selections. Among them was Simple Aveu which was delicately rendered in a fine fashion. Mose walked in around this time, and after the professor left the bench, he sat down, fooled around for a moment, and then launched into a ragtime version of the same piece. The article's author called on a number of wild superlatives to describe the bombastic performance. In spite of the tumultuous applause, it evidently left Herr Pützenjammer enraged, and he shouted at the crowd of ignorant "dumkopfs" as he exited the room. In general, Mose was known to be one of the most genial of people with a wonderful voice and affable sense of humor.

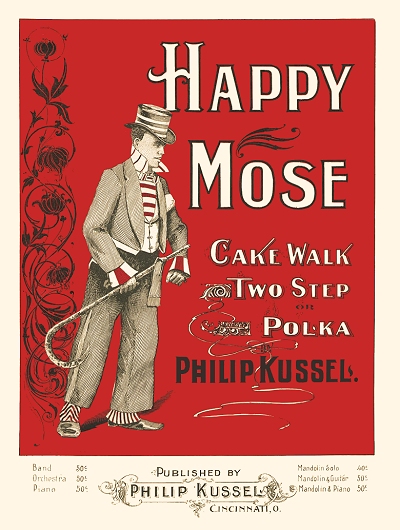

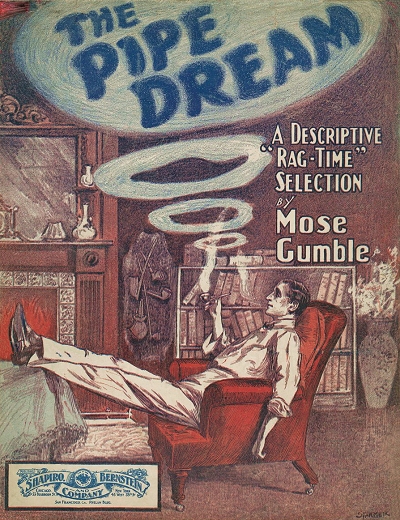

It noted how he would usually appear after ten o'clock, a time after the proper and genteel people would have left the club-house at the college in Cincinnati where he was often heard. He was evidently reluctant to get started, but once at the piano would take over the room. "Mose could no more have kept away from a piano than a rabbit from a cabbage patch." The author called Gumble's repertoire "voluminous and vast," stating he seemed to know every "coon" song under the sun, and even noting that Mose played one or two of his own compositions, although none had been in print to that time. One incident was cited in which Professor Pützenjammer, a distinguished piano teacher, walked in one evening to play a few selections. Among them was Simple Aveu which was delicately rendered in a fine fashion. Mose walked in around this time, and after the professor left the bench, he sat down, fooled around for a moment, and then launched into a ragtime version of the same piece. The article's author called on a number of wild superlatives to describe the bombastic performance. In spite of the tumultuous applause, it evidently left Herr Pützenjammer enraged, and he shouted at the crowd of ignorant "dumkopfs" as he exited the room. In general, Mose was known to be one of the most genial of people with a wonderful voice and affable sense of humor.Strangely enough, Gumble's next foray into the published music world was a composition referring to him, but composed by his friend Philip Kussel. Happy Mose was a simple cakewalk that depicted a well-dressed black man on the cover, but was clearly dedicated to Mose on the inside. The title was a nickname he had picked up while at the music school. Mose was obviously interested in doing something more in music, and he made some more attempts at composition, releasing a quartet of pieces in 1901 that were published in Cincinnati and Indianapolis. The most enduring of these was his Japanese Rag which eventually found its way to some piano roll recordings. The following year brought his most substantial hit in his short-lived composition career, The Pipe Dream. Published in Chicago by Shapiro, Bernstein, and arranged by the talented William Tyers, it saw distribution in New York City as well, selling fairly well.

When the initial opportunity for Mose to venture from Cincinnati to the professional ranks of a New York publisher was offered, he was reluctant to make the leap. As reported in The Music Trade Review of January 19, 1901: "Mose Gumble, of Cincinnati, O., who was engaged to go to New York and take charge of a branch of the music business of Monroe H. Rosenfeld, has decided not to leave that city." Later in 1901 he was based for a short time in Indianapolis, but soon spent some time in both Chicago and Manhattan.  Mose quickly became fairly well known as a fine singer at many venues. When he decided to finally accept a position, there is early mention of one of his initial moves in The Music Trade Review of February 1, 1902: "Mose Gumble leaves New York for Chicago to-morrow morning, where he will assume the management of the Chicago branch of Shapiro, Bernstein & Von Tilzer. Mr. Gumble comes from Cincinnati and is an accomplished musician, well known and popular among performers. He will make a good man for that position."

Mose quickly became fairly well known as a fine singer at many venues. When he decided to finally accept a position, there is early mention of one of his initial moves in The Music Trade Review of February 1, 1902: "Mose Gumble leaves New York for Chicago to-morrow morning, where he will assume the management of the Chicago branch of Shapiro, Bernstein & Von Tilzer. Mr. Gumble comes from Cincinnati and is an accomplished musician, well known and popular among performers. He will make a good man for that position."

Mose quickly became fairly well known as a fine singer at many venues. When he decided to finally accept a position, there is early mention of one of his initial moves in The Music Trade Review of February 1, 1902: "Mose Gumble leaves New York for Chicago to-morrow morning, where he will assume the management of the Chicago branch of Shapiro, Bernstein & Von Tilzer. Mr. Gumble comes from Cincinnati and is an accomplished musician, well known and popular among performers. He will make a good man for that position."

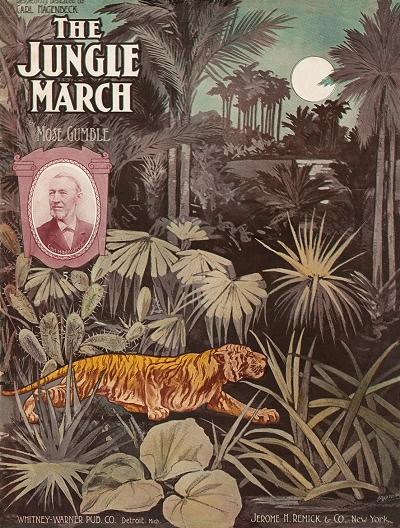

Mose quickly became fairly well known as a fine singer at many venues. When he decided to finally accept a position, there is early mention of one of his initial moves in The Music Trade Review of February 1, 1902: "Mose Gumble leaves New York for Chicago to-morrow morning, where he will assume the management of the Chicago branch of Shapiro, Bernstein & Von Tilzer. Mr. Gumble comes from Cincinnati and is an accomplished musician, well known and popular among performers. He will make a good man for that position." In 1903 Gumble composed another moderate hit, Minstrel Sam. He was given an opportunity to plug a new Jean Schwartz song in public, Bedelia, and it is said that his performances turned it into a big hit. Along the way he met singer Clara Etta Black (some sources cite Ella), later known as Clarice Vance, The Southern Nightingale or The Southern Singer. They were an interesting pair, as Clarice was over six feet tall to Mose's medium height. Clarice had already built a good reputation, performing "coon songs" since the early 1890s, and had been previously married two times. She divorced her second husband, John F. Blanchard, just months before she and Mose married on December 7, 1904 in Indianapolis. It would be some time before their marriage would be commonly acknowledged in public. Around that same time he was hired away from Shapiro, Bernstein by Jerome H. Remick, and at fifteen dollars per week he became one of the best paid song pluggers and professional managers of his age in the country. It was also in 1904 that younger brother Albert Gumble started his lengthy own career as a songwriter.

For the next several years, Mose was employed as both a manager and plugger with Remick. Among the pieces he helped turn into hits were Shine On, Harvest Moon, Put On Your Old Grey Bonnet, In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree, Smiles, and By the Light of the Silv'ry Moon. Mose would utilize many techniques to get a song instantly known at what seemed like an ad-hoc appearance at a rooftop garden show or vaudeville theaters. He would employ plants in the audience, stooges to make comedic entrances, even water boys. One early plant used by Mose was singer Al Jolson. There were times that Mose would sleep on the beach at Coney Island during multi-day sojourns through the many dance halls at Brighton Beach and westward, always with a bundle of demonstration sheets under his arm. He would make sure that audiences would quickly pick up the catchy refrains, and even have them or his plants insist on encores. He was often referred to as the Dean of song pluggers.

A typical report on the Remick firm intended for the trades was found in the December 29, 1906 issue of The Music Trade Review: "Mose Gumble, manager of the professional department, speaking for Jerome H. Remick & Co., said:

By George, we have not had a dull month—in fact, scarcely a day—throughout the year. Every month has shown an increase in business, and in talking the matter over with Mr. Belcher (the manager) relative to pushing sales, we have concluded very little could be added to our efforts and energy with this end in view. We have kept pounding away, and invariably an increase would materialize. The outlook is great and nothing is in sight to disturb our cheerfulness regarding business for next year. We have some crackerjacks up our sleeve. The aggregate of sales - on which our trade is based - for 1906 looks good.

A 1907 passport application listed Gumble as a manager in the music business. The issuance of the document was followed by a trip to Europe, reported in The Music Trade Review of May 11, 1907: "Mose Gumble, manager of the professional department of Jerome H. Remick & Co., New York, went abroad Wednesday on the steamer 'Baltic,' of the White Star line.

He will be away several weeks. 'Clarice Vance,' the popular vaudeville singer, who is Mrs. Gumble in private life, accompanies her husband on this pleasure trip. Mose and his estimable wife have the good wishes of everybody on their journey—a perpetual honeymoon, as it were."

|

When Remick resituated to a larger building in 1908, the importance of the firm's professional department and the nature of their new digs was described in the March 28, 1908 Music Trade Review:: "The professional department is, of course, a model of comfort and luxury, as befits the ladies and gentlemen of the dramatic profession, who have long since regarded the music publishing industry as one run in their own special interests. This department takes up the entire third floor, which has been divided into eleven rooms, one of which will be devoted to the use of the popular Mose Gumble. The walls, however, have not been padded, and therefore professionals who have voices like the horns used on election night will be able to make themselves as objectionable to their neighbors as they please, without any serious interference. The fifth floor will no doubt be designated 'The Remick Club,' for here the social end of the Remick institution will be upheld. It is here that the Remick barber will shave the Remick employes while they wait, and here both Messrs. Williams and Van Alstyne may be induced to indulge in an occasional hair cut. Mose Gumble, however, will content himself with a hasty shampoo, and it is not unlikely that the sweet voiced little lady who attends to the telephone will take the opportunity of frequently having a marcel wave put in her raven hair."

The 1910 enumeration listed Mose as a publisher, although he was still working in the same role in the Remick corporation. This is underscored in the February 19, 1910 issue of The Music Trade Review:

Mose Gumble, manager of the professional departments of Jerome H. Remick & Co., New York City, has spent this week in Chicago, and his visit marked both a new extension of the Remick policy and the enlargement of the activities of the genial and very energetic Gumble. Hereafter he will have entire charge of the professional work of the house of Remick. In other words, the professional departments in New York, Detroit, Chicago, and even the new branches in San Francisco and Los Angeles will be under one direction and will report to Mr. Gumble in New York. As a consequence, Chicago will see more of Mr. Gumble in the future than in the past. His visit here is a very satisfactory one. He is greatly pleased with the new offices in the Majestic building, which, in company with Billy Thompson, local professional manager, he selected. This is his first trip to Chicago, however, since the new quarters were occupied. He speaks very highly of the intelligent work done by Mr. Thompson and his efficient aids.

Happy Mose did have some unhappiness in his life. Clarice was becoming somewhat quirky in her behavior. She had also done some song plugging for him, but would refuse to take on anything even mildly suggestive, as many songs of the early teens clearly were. It was said she "gives those to her husband for cigar lighters." Just the same, she continued singing coon songs, and eventually recorded a number of sides for Victor in 1909. After that series she did not record any more, offering no explanation. With Clarice continuing to work on finding engagements, and Mose traveling around the country for Remick, relations became strained. The couple finally divorced in 1914, and Clarice left the stage for the most part soon thereafter. She married at least one more time to a writer for Universal Pictures, but he committed suicide in 1928.

Mose continued on more in the capacity of a professional manager for Remick throughout the 1910s, and by 1917 he was reported as making "regular monthly tours through the Eastern territory." He was also in charge of the composers of the firm, and likely reviewing their work for sales potential. One of his more famous charges was George Gershwin, who was hired to the staff by Mose as a plugger on the piano when he was just 15. This lasted less than two years as the youngster was trying to prove himself as a composer, not just a boy wonder at the keys. Finally, Mose had dealt with enough of George's constant submissions, telling him to "leave the composing to the composers," and eventually firing the future American treasure, something he was often reminded of in later years. For the 1918 draft registration he was listed his employer as Jerome Remick, and in 1920 he was listed as a publisher of music, living in Manhattan with his mother, sister Lily, and brother-in-law Maxwell Moss.

Remick was continuing to open new branches, including Toronto, Canada, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and in Texas and California. The strain of this level of work keeping up with growth eventually got to Mose, and it was reported in Variety that he was hospitalized for a "complete nervous breakdown" in 1919. After a short rest he was back on the job for Remick. Even after 16 years with the firm, Gumble's first trip to the west did not occur until 1920 as reported in the trades in early December: "Mose Gumble, representative of the Jerome H. Remick Co., is on the Pacific Coast, looking over the territory for the first time. He has arranged to open several new Remick Song Shops in Texas and other Southern States." Gumble typically oversaw the opening of the new branches, and by now was Remick's most trusted traveling representative and manager.

Continuing in his position as a general manager for Remick through most of the 1920s, Mose abruptly resigned when the firm was sold to manager Jerome Keit in May 1928. He immediately teamed up with Walter Douglas and Walter Donaldson to form Donaldson, Douglas and Gumble, which debuted at 1595 Broadway, Manhattan, on June 1, 1928 with a well-attended opening ceremony. As announced in The Music Trade Review of May 19, 1928: "Mose Gumble, who has been with the Remick firm for twenty-eight years, since its inception in 1900 [actually since 1904], is also a valuable member of the new firm, being well known to the leading vaudeville teams and orchestra leaders of the country." He was reportedly afforded $300 a week for his services. Composer Donaldson was considered the owner and Douglas and Gumble the employees, with Mose's official title being Professional Manager. Later in the year Gumble had some medical issues which required an unspecified surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, but was he back at work by late October.

When the remains of the Remick firm were sold to Warner Brothers in 1929, Gumble was reacquired by the new Warner Music on a part time basis to assist with their catalog and be their East Coast representative. In 1930 he seems to have had another job as well, listed as a salesman in a music store. In 1938 he left Donaldson, Douglas and Gumble and went to Warner Brothers on a full time basis, his official title being the Manager of Exploitation Department of All Standard Songs. His former wife Clarice appeared as an extra in a 1937 Warner Brothers picture, which coincides with his first work for that company, but whether he secured her the position or not is speculation. She subsequently moved to San Francisco and died in a California state hospital of advanced dementia in 1961.

In the late 1930s Mose founded the Music Publishers Contact Men's Association, a relief organization for employees of publishing firms to help them through hard times. From the late 1930s into the 1940s Mose was somewhat of a celebrity among the many celebrities living in Manhattan, having a table reserved for him for lunchtime meetings for many years at either Martin's or Toots. Here he would spend hours talking about the early days of show business, something that may have held some fascination for younger composers and entertainers. This was also good public relations for Warner Brothers as his legacy lent credence to their music department. As of the 1940 census, taken in Manhattan, he was still lodging with the Maxwells, listed as a "contact man" in music publishing.

Gumble remained with Warner Brother's music literally up until his death. In late September of 1947 Mose boarded the 20th Century limited from New York to Los Angeles, on the way to meet with singers Dinah Shore and Rudy Vallee and composer Harry Warren among others. He was found dead of a heart attack in his compartment around Elkton, Illinois, having recently turned 71-years-old. On September 29 Mose was laid to rest in a Jewish cemetery in his home of New York City. "Happy Mose" Gumble was mostly remembered by his friends in the music business, and not so much the public. Still, much of what he did shaped the musical tastes of much of the buying public in the early years of the 20th century.

Thanks go to the biographer of Clarice Vance, Sterling Morris of Seattle, Washington, for additional information on the eccentric Mrs. Gumble. Also to collector and historian Jeremy Stevenson who located one of the earlier Gumble pieces not listed at the Library of Congress.

Compositions

Compositions