There are some stories in the history of American music that have definitive intersections with others, and it can be hard to separate many parts of their story from the other. This is one of them, and while both biographies dealing with this couple do have separate beginnings, and some of the content in the middle is unique to that individual, for the most part they are tandem in many ways. It is a story of one of the more enduring, successful, and at times controversial couples of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley - Max and Gertrude Hoffmann.

Max was born in Gniezno [Gnesen], Poland (on one passport he claimed Birubaum, Poland) as the rather formal and lengthy Adolph Eugene Victor Maximilian Hoffmann. He was possibly the only child, at least surviving child, of Joseph Hoffmann (one source suggests Julius) and Agnes Von Donat. (Note that Hoffmann was often seen as Hoffman in some publications, but the former will be used here as the established correct spelling.) The family immigrated to the United States, arriving on August 15, 1879, and soon relocated to Saint Paul, Minnesota, which had a large Polish and Russian community. They were difficult to pinpoint in the 1880 enumeration and directory records are uncertain, so it is unclear what Joseph did for a living. He died in the late 1880s. Agnes soon became a fruit seller, and Max, as his name was now shortened to, who had evidently received at least some formal musical training, started listing himself as a musician in Saint Paul directories in 1889 at age 15. By 1894 he was also listed as a music teacher. Agnes appears to have died in the mid-1890s as no more listings were found for her.

There are suggestions made by Isidor Witmark in his pseudo-autobiography, from Ragtime to Swingtime, that Max may have done some arranging work in Chicago, as well as fronted a vaudeville orchestra at the Olympic Theater for as long as six years. However, his appearance in the 1894 Saint Paul directory and subsequent relocation to New York City that same year make that possibility seem less than likely. At 6'2" with piercing bluish-gray eyes he was tall and handsome, so quite noticeable wherever he went in Manhattan. Some sources have suggested that "Baron" had been affixed to Hoffmann's name at some point, but given his separation from his home country and upbringing in Saint Paul, plus a lack of clear evidence to support this contention,

it seems unlikely that this moniker was applied except in passing, and he claimed it to be perpetuated by one of his early press agents. After meeting singing comedienne and actress Atlanta J. "Attie" Spencer, the couple was married in Manhattan on February 2, 1895.

|

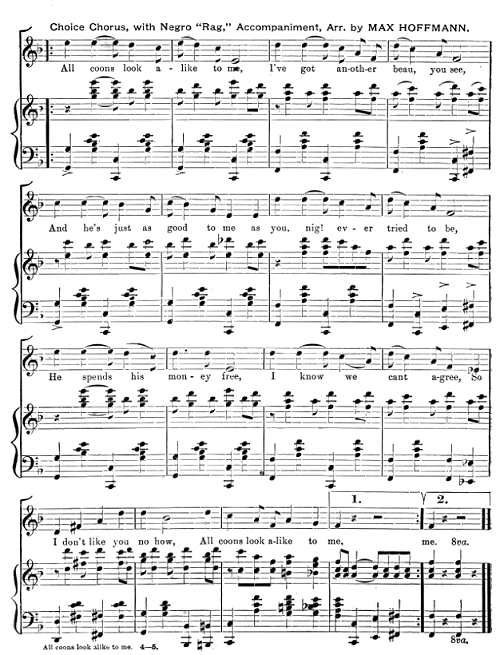

Max was confirmed to have been in some traveling theatrical companies as a conductor and pianist prior to his relocation. He soon established himself as a capable arranger of both piano and orchestral scores, and his quality work created somewhat of a demand for his services. After an early song composed and self-published by lyricist Dave Marion, he landed a steady job with publisher M. Witmark and Sons as an orchestral arranger and editor. He became so engaged with it that when he assembled an orchestra he tended to hire musicians who were also capable arrangers to parse the work out. Among the early piano accompaniments he scored for the Witmarks in 1896 are what may be considered the first notated ragtime music in publication, including the ethnic songs with unfortunate connotations but still musically important, All Coons Look Alike to Me by Ernest Hogan and My Coal Black Lady by W.T. Jefferson. In fact, the sheet music for All Coons Look Alike to Me touted his work as a "Choice Chorus, with Negro 'Rag,' Accompaniment, arr. by MAX HOFFMANN." Indeed, both the melodic line and, at times, the accompaniment feature syncopations tied over the middle of a measure, separating this from the cakewalk compositions which were becoming increasingly popular at this time. While these syncopations may have been suggested or performed by Hogan, it was Max who set a standard on how to notate them, albeit in 4/4 time instead of the 2/4 signature that would soon become the normal meter for ragtime. For his efforts he received $5, which was actually above average for that time for a piano score. When the vivacious stage singer May Irwin made a hit out of the tune in 1896, it gave Max a great deal of added visibility among those in the music publishing world.

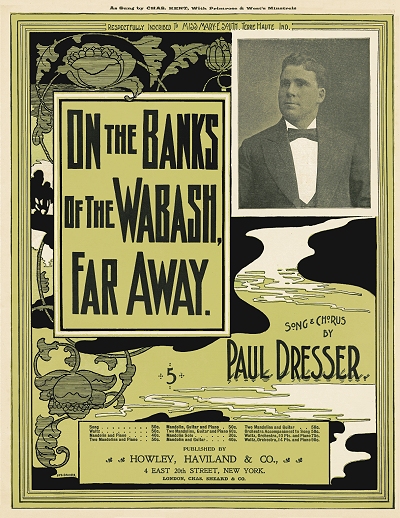

Among those he crossed paths with were composer and publishing partner Paul Dresser, part of the firm Howley, Haviland & Dresser. While he was a capable songwriter, he did not possess inate skills in notation or transcription, so usually called on an arranger to do so for him. In that regard, Max was engaged to help him with his soon-to-be hit, On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away. While it was thought that his brother Theodore Dresser had provided the famous lyrics for the tune, Isidore Witmark recalled something quite different, quoting Max directly about the topic.

I went to his room at the Auditorium Hotel [Chicago, Illinois], where instead of a piano there was a small folding camp organ, which Paul always carried with him. It was summer; all the windows were open and Paul was mulling over a melody that was practically in finished form. But he did not have the words. So he had me play the full chorus over and over again for at least two or three hours, while he was writing down words, changing a line here and a phrase there until at last the lyric suited him. He had a sort of dummy refrain which he was studying; but by the time he finished what he was writing down to my playing it was an altogether different lyric.

When Paul came to the line, "Through the sycamores the candle lights were gleaming," I was tremendously impressed. It struc me at once as one of the most poetic inspirations I had ever heard. I have always felt that Paul got the idea from glancing out of the window now and again as he wrote, and seeing the lights glimmering out on Lake Michigan. We spent many hours together that evening, and when Paul finished he asked me to make a piano part for publication at the earliest moment. I happened to have some music paper with me, and I wrote one right out, on the spot. This I mailed to Pat Howley, one of Dresser's Partners, sending it to the New York Office at Thirty-second Street and Broadway. At Paul's request I also enclosed my bill.

This piano part contained the lyric as Paul (and no one else) wrote it that night in my presence. The song was published precisely as I arranged it. They did not send proofs for me to read; the proofs were read in New York, to save time. During the whole eveng we spent together, Paul made no mention of anyone's having helped him with the song.

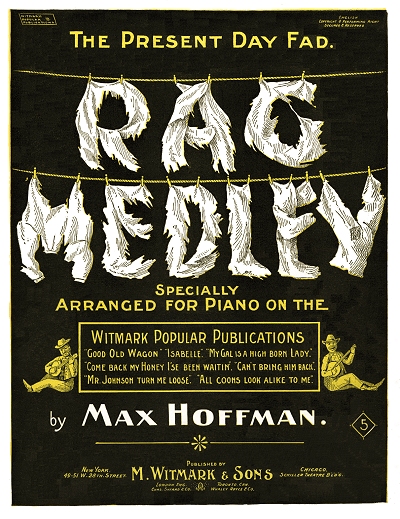

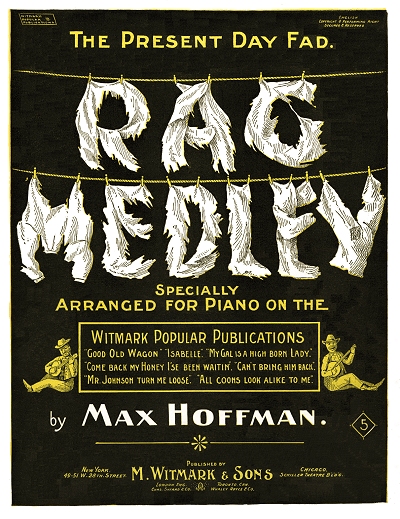

The sentimental song, with Hoffman's arrangement, had a big sale in 1897. That same year, in addition to several more accompaniments to songs, many likely uncredited, Witmark issued a song and two instrumentals with music by Max. One of those was his Rag Medley, and although it was ostensibly a literal medley of existing "coon songs" from the Witmark catalog of the prior two years, his new instrumental arrangements of the strains turned this into an authentic work of ragtime that was somewhat advanced for that time. Among the inclusions were Hogan's All Coons Look Alike and Ben Harney's songs You've Been a Good Old Wagon, But You Done Broke Down and Mister Johnson, Turn Loose, popular by this time in vaudeville. Max had arranged similar ragtime choruses for their original publications. The medley incorporated syncopated passages in the left hand and several instances of mid-measure syncopations in the right. It was followed in 1898 by Ragtown Rags: Medley, and in 1899 by A Night in Coontown: Medley, each one a bit more refined than the last but similar in makeup. Although they were similarly arrangements of the "Latest Coon Song Hits" from the Witmark catalog, most originally touched by Max, the adaptations to instrumental form might also be considered on their own merit to be mostly original in content. One of those tunes, Bom-Ba-Shay, had indeed been composed by Max in 1897, and even introduced to the stage by his wife Attie. Hoffmann's arranging and orchestration work for Witmark continued on through to the new century, and he would become the musical director of the Broadway Theater before the old century was out.

One of those was his Rag Medley, and although it was ostensibly a literal medley of existing "coon songs" from the Witmark catalog of the prior two years, his new instrumental arrangements of the strains turned this into an authentic work of ragtime that was somewhat advanced for that time. Among the inclusions were Hogan's All Coons Look Alike and Ben Harney's songs You've Been a Good Old Wagon, But You Done Broke Down and Mister Johnson, Turn Loose, popular by this time in vaudeville. Max had arranged similar ragtime choruses for their original publications. The medley incorporated syncopated passages in the left hand and several instances of mid-measure syncopations in the right. It was followed in 1898 by Ragtown Rags: Medley, and in 1899 by A Night in Coontown: Medley, each one a bit more refined than the last but similar in makeup. Although they were similarly arrangements of the "Latest Coon Song Hits" from the Witmark catalog, most originally touched by Max, the adaptations to instrumental form might also be considered on their own merit to be mostly original in content. One of those tunes, Bom-Ba-Shay, had indeed been composed by Max in 1897, and even introduced to the stage by his wife Attie. Hoffmann's arranging and orchestration work for Witmark continued on through to the new century, and he would become the musical director of the Broadway Theater before the old century was out.

One of those was his Rag Medley, and although it was ostensibly a literal medley of existing "coon songs" from the Witmark catalog of the prior two years, his new instrumental arrangements of the strains turned this into an authentic work of ragtime that was somewhat advanced for that time. Among the inclusions were Hogan's All Coons Look Alike and Ben Harney's songs You've Been a Good Old Wagon, But You Done Broke Down and Mister Johnson, Turn Loose, popular by this time in vaudeville. Max had arranged similar ragtime choruses for their original publications. The medley incorporated syncopated passages in the left hand and several instances of mid-measure syncopations in the right. It was followed in 1898 by Ragtown Rags: Medley, and in 1899 by A Night in Coontown: Medley, each one a bit more refined than the last but similar in makeup. Although they were similarly arrangements of the "Latest Coon Song Hits" from the Witmark catalog, most originally touched by Max, the adaptations to instrumental form might also be considered on their own merit to be mostly original in content. One of those tunes, Bom-Ba-Shay, had indeed been composed by Max in 1897, and even introduced to the stage by his wife Attie. Hoffmann's arranging and orchestration work for Witmark continued on through to the new century, and he would become the musical director of the Broadway Theater before the old century was out.

One of those was his Rag Medley, and although it was ostensibly a literal medley of existing "coon songs" from the Witmark catalog of the prior two years, his new instrumental arrangements of the strains turned this into an authentic work of ragtime that was somewhat advanced for that time. Among the inclusions were Hogan's All Coons Look Alike and Ben Harney's songs You've Been a Good Old Wagon, But You Done Broke Down and Mister Johnson, Turn Loose, popular by this time in vaudeville. Max had arranged similar ragtime choruses for their original publications. The medley incorporated syncopated passages in the left hand and several instances of mid-measure syncopations in the right. It was followed in 1898 by Ragtown Rags: Medley, and in 1899 by A Night in Coontown: Medley, each one a bit more refined than the last but similar in makeup. Although they were similarly arrangements of the "Latest Coon Song Hits" from the Witmark catalog, most originally touched by Max, the adaptations to instrumental form might also be considered on their own merit to be mostly original in content. One of those tunes, Bom-Ba-Shay, had indeed been composed by Max in 1897, and even introduced to the stage by his wife Attie. Hoffmann's arranging and orchestration work for Witmark continued on through to the new century, and he would become the musical director of the Broadway Theater before the old century was out.The 1900 enumeration showed Max and Attie residing in Manhattan, listed respectively as a musician and an actress.

Attie Spencer c.1900 Attie had been rising up through the ranks in the vaudeville houses of lower New York City and on the touring circuits since around 1895. That same census year of 1900 would see Mrs. Hoffmann, billed as Attie Spencer, working at Tony Pastor's famous vaudeville house as a headliner along with singer Emma Carus. A later article noted that their marriage had been troubled almost from the beginning, and she claimed not only that Max had not supported her in the style to "which she had been accustomed," but that "he did not support her in any style whatsoever." Attie would never rise to full stardom, but stayed busy for the next decade just the same, leading her own troupe at one point. However, around this time, a new force appeared in Max's life, one that would alter it in a number of ways, as he would affect hers.

Attie Spencer c.1900

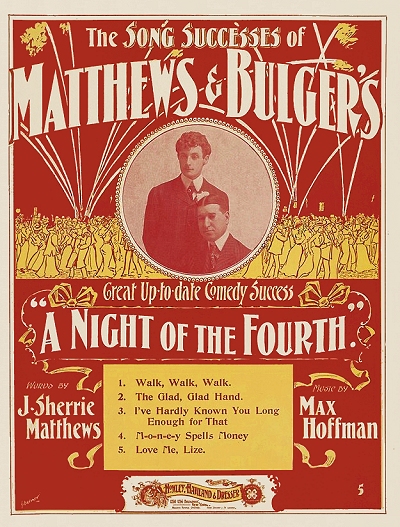

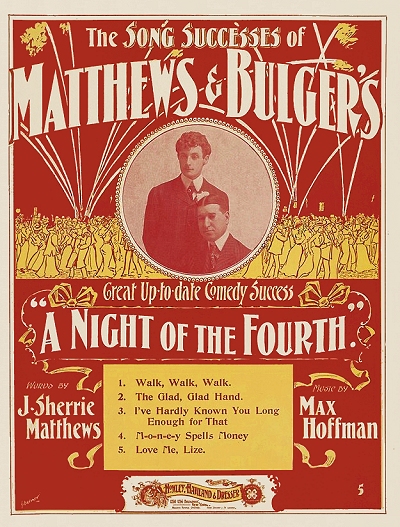

She was born in San Francisco, California, in 1883 as Katherine Gertrude Hay, and had been working the stages of the West Coast billed as "Kitty Hayes" for a few years. Around 1900, Katherine was spotted by actress Florence Roberts while playing a French Dancer in an opera at the Alcazar Theater in San Francisco, and Florence encouraged the soubrette to consider a career in dance. At the age of seventeen Hay signed on with a show starring Sherrie Matthews and Harry Bulger, and followed them on a continental tour. It was a musical play titled The Night of the Fourth by George Ade, and Max had been contracted to write songs for it with lyricist J. Sherrie Mathews. He had been writing music specifically for a number of well-known troupes, including those of producers Marcus Klaw & Abraham L. Erlanger, and finding more work conducting orchestras and running rehearsals. As a result, he was evidently on the road during the tryouts. Gertrude, playing the small part of Miss Judge, was quickly noticed by Max, and they and struck up a serious relationship. Having gone through many adjustments on the road in late 1900, the play and its weary cast made it to Hammerstein's Theater for a January 21 debut. As it happens, Max was also the musical director for the run at Hammersteins. There were many tepid reviews of the show on its opening, one of them calling it "absolute drivel, pointless chatter and purposeless dialogue." However, Gertrude being a young woman who was naturally sensuous and alluring, and even considered vexing by many who watched her dance, was a standout, and Max stood with her.

It was a musical play titled The Night of the Fourth by George Ade, and Max had been contracted to write songs for it with lyricist J. Sherrie Mathews. He had been writing music specifically for a number of well-known troupes, including those of producers Marcus Klaw & Abraham L. Erlanger, and finding more work conducting orchestras and running rehearsals. As a result, he was evidently on the road during the tryouts. Gertrude, playing the small part of Miss Judge, was quickly noticed by Max, and they and struck up a serious relationship. Having gone through many adjustments on the road in late 1900, the play and its weary cast made it to Hammerstein's Theater for a January 21 debut. As it happens, Max was also the musical director for the run at Hammersteins. There were many tepid reviews of the show on its opening, one of them calling it "absolute drivel, pointless chatter and purposeless dialogue." However, Gertrude being a young woman who was naturally sensuous and alluring, and even considered vexing by many who watched her dance, was a standout, and Max stood with her.

It was a musical play titled The Night of the Fourth by George Ade, and Max had been contracted to write songs for it with lyricist J. Sherrie Mathews. He had been writing music specifically for a number of well-known troupes, including those of producers Marcus Klaw & Abraham L. Erlanger, and finding more work conducting orchestras and running rehearsals. As a result, he was evidently on the road during the tryouts. Gertrude, playing the small part of Miss Judge, was quickly noticed by Max, and they and struck up a serious relationship. Having gone through many adjustments on the road in late 1900, the play and its weary cast made it to Hammerstein's Theater for a January 21 debut. As it happens, Max was also the musical director for the run at Hammersteins. There were many tepid reviews of the show on its opening, one of them calling it "absolute drivel, pointless chatter and purposeless dialogue." However, Gertrude being a young woman who was naturally sensuous and alluring, and even considered vexing by many who watched her dance, was a standout, and Max stood with her.

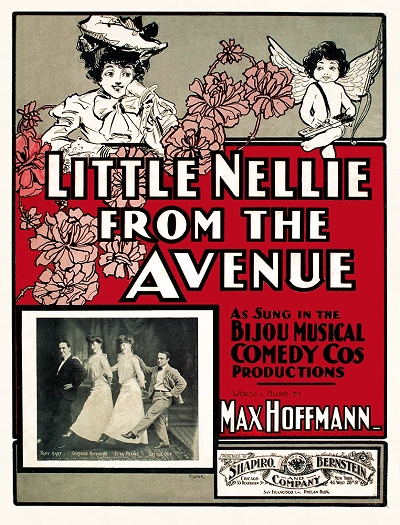

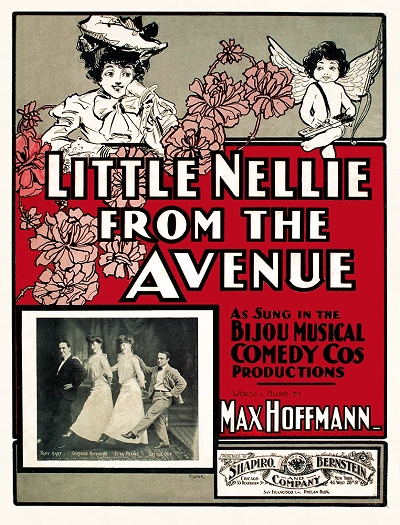

It was a musical play titled The Night of the Fourth by George Ade, and Max had been contracted to write songs for it with lyricist J. Sherrie Mathews. He had been writing music specifically for a number of well-known troupes, including those of producers Marcus Klaw & Abraham L. Erlanger, and finding more work conducting orchestras and running rehearsals. As a result, he was evidently on the road during the tryouts. Gertrude, playing the small part of Miss Judge, was quickly noticed by Max, and they and struck up a serious relationship. Having gone through many adjustments on the road in late 1900, the play and its weary cast made it to Hammerstein's Theater for a January 21 debut. As it happens, Max was also the musical director for the run at Hammersteins. There were many tepid reviews of the show on its opening, one of them calling it "absolute drivel, pointless chatter and purposeless dialogue." However, Gertrude being a young woman who was naturally sensuous and alluring, and even considered vexing by many who watched her dance, was a standout, and Max stood with her.The play closed after fourteen performances, and Hoffmann's current marriage was not far behind. Although it escaped major publicity and scandal somehow, Max would soon be divorced from Attie, who called Gertrude a co-respondent in the uncontested divorce trial. Given that she would very soon be married to John Koster of the Koster & Bial theater organization, and divorce him within a year to marry somebody else, it is probable that Attie was just as responsible for their dissolution. After a whirlwind romance, Max and eighteen-year-old Gertrude were married on April 7, 1901, virtually hours after his divorce had been granted in Chicago, during a stint in Norfolk, Virginia, with the Bijou Musical Comedy Company. Perhaps as a formality they also had a ceremony the following day in Manhattan, New York. Max, Jr. was coincidentally born in Norfolk during another tour of the troupe in December 1902. During that period of 1901 into 1903, Max wrote some of the songs for the Bijou company, and Gertrude would both choregraph and dance in selected numbers. Max was also the composer and musical director of Frank McKeen's Champagne Charley in late 1901, although the show did not make it to Broadway. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.

Max was also the composer and musical director of Frank McKeen's Champagne Charley in late 1901, although the show did not make it to Broadway. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.

Max was also the composer and musical director of Frank McKeen's Champagne Charley in late 1901, although the show did not make it to Broadway. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.

Max was also the composer and musical director of Frank McKeen's Champagne Charley in late 1901, although the show did not make it to Broadway. The Hoffmanns would both make a name for themselves during a summer of 1902 stint at the Brooklyn Orpheum and the New York Theater Roof Garden, appearing on the same bill as the important African American duo of Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, and in her sixth month of pregnancy performing My Pretty Zulu Lu composed by Max.Within a few months of their son's birth Gertrude was already dancing at the Paradise Roof Garden on top of the Victoria Theater in New York City, run by no less than Oscar Hammerstein, Sr. The boss was impressed, so Max was hired to write and arrange for them, and Gertrude, all of twenty, was engaged to assist director Frank Tannehill with rehearsals and choreography. Her main assignment was the Punch and Judy Company, a vaudeville revue that played at the Paradise from June through early September of 1903. More opportunities came for Gertrude over the next couple of years as she built her reputation and dance repertoire as both a dancer and creative choreographer.

In the interim, Max had issued several songs in 1902 and 1903 that were standard popular fare, including ethnic numbers for the Bijou company, so it is likely that not all of them saw their way into print, depending on the audience reception in the show. The majority of them were penned completely by Max, both words and music, but no real hits emerged, and there were no instrumental numbers either. A couple of tunes were co-written with established lyricist Andrew B. Sterling. They were competent enough to grab the attention of Gus and Max Rogers, who had been working as The Rogers Brothers in vaudeville since 1885, and had moved to the "legitimate" Broadway stage around 1899. They became known for their location shows, such as The Rogers Brothers in Washington and The Rogers Brothers in Harvard. In mid-1903, Max was engaged by the brothers for their next venture, The Rogers Brothers in London, composing music to libretto and lyrics by Edward Gardenier, who had already written for them, and George V. Hobart, who was a newcomer. Up until that time, Maurice Levi had been providing their music, but he parted ways with the brothers to pursue new horizons, leaving the opening for Hoffmann. This began a multi-year association with the talented brothers, and some minor hits as well. It also provided financial security that would allow Gertrude some freedoms to pursue new directions in her own career.

In mid-1903, Max was engaged by the brothers for their next venture, The Rogers Brothers in London, composing music to libretto and lyrics by Edward Gardenier, who had already written for them, and George V. Hobart, who was a newcomer. Up until that time, Maurice Levi had been providing their music, but he parted ways with the brothers to pursue new horizons, leaving the opening for Hoffmann. This began a multi-year association with the talented brothers, and some minor hits as well. It also provided financial security that would allow Gertrude some freedoms to pursue new directions in her own career.

In mid-1903, Max was engaged by the brothers for their next venture, The Rogers Brothers in London, composing music to libretto and lyrics by Edward Gardenier, who had already written for them, and George V. Hobart, who was a newcomer. Up until that time, Maurice Levi had been providing their music, but he parted ways with the brothers to pursue new horizons, leaving the opening for Hoffmann. This began a multi-year association with the talented brothers, and some minor hits as well. It also provided financial security that would allow Gertrude some freedoms to pursue new directions in her own career.

In mid-1903, Max was engaged by the brothers for their next venture, The Rogers Brothers in London, composing music to libretto and lyrics by Edward Gardenier, who had already written for them, and George V. Hobart, who was a newcomer. Up until that time, Maurice Levi had been providing their music, but he parted ways with the brothers to pursue new horizons, leaving the opening for Hoffmann. This began a multi-year association with the talented brothers, and some minor hits as well. It also provided financial security that would allow Gertrude some freedoms to pursue new directions in her own career.The Rogers Brothers announced in July 1904 that they Max had been engaged for their next production, The Rogers Brothers in Paris, noting that he would be the music director and would write the entire score with Gardenier and Hobart. As soon as the ink was dry and the production opened on the road in August in Buffalo, then September on Broadway, Hoffmann and lyricist Vincent Bryan (who would soon write lyrics to In My Merry Oldsmobile) were engaged by Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon to provide songs for the comedy Me, Him and I, for which the dance numbers were choregraphed by Gertrude. It opened in December 1904 and ran for an underwhelming 24 performances. However, the collaboration helped to launch Gertrude's career as a songwriter, as in 1905 she teamed with Bryan, who had his own small publishing concern at that time. They wrote a few songs that were published over the next several months, the last couple of them issued by Jerome H. Remick. Each piece was probably scored by Max, although he did not take credit. One of them, G.O.P. after the Grand Old [Republican] Party is oddly timed, since the last election had been months before, but was likely associated with the show Fantana, or perhaps The Duke of Duluth. The remainder of the pieces were also used in various shows. For the fall of 1905, The Rogers Brothers decided to visit Ireland and take Hoffman and Hobart along with them.

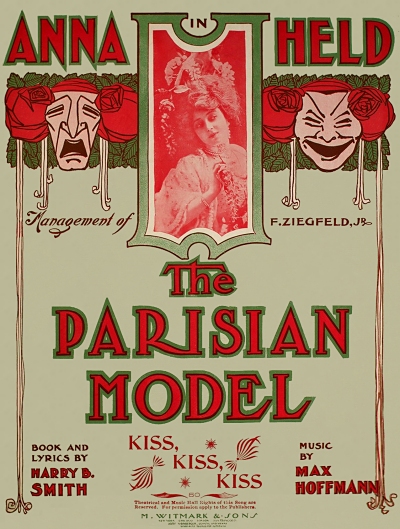

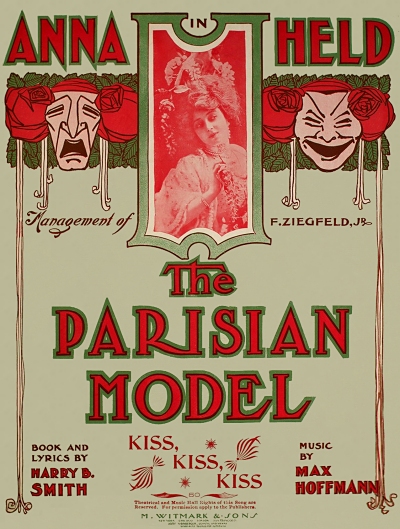

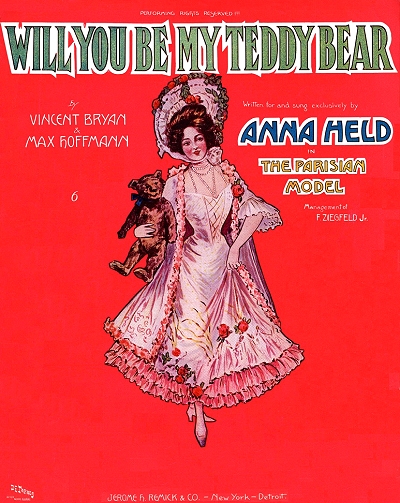

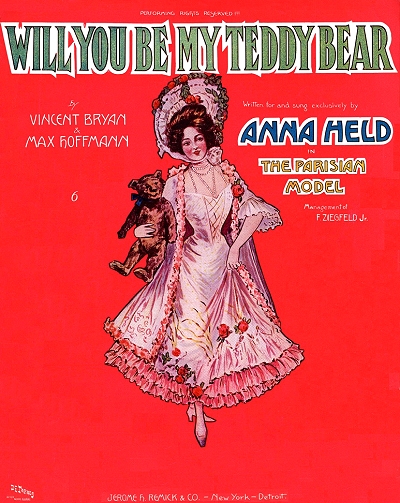

Then came the big break that helped solidify the careers of multiple parties. In late 1906 theatrical entrepreneur and producer Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., was planning on staging A Parisian Model, in part as a vehicle to feature and appease his talented but often prickly French wife (actually born in Poland), Anna Held. For this production, Max was teamed with Harry B. Smith provided the bulk of the lyrics, but Gertrude and Max wrote at least one piece together, On San Francisco Ban, their only know collaboration. Gertrude was somehow involved on stage during out-of-town previews. In a scene worthy of the storyline of the film 42nd Street, the lead performer became ill and Gertrude was brought in as a ringer. Performing the song I Just Can't Make My Eyes Behave (ironically the hit but the only one that Max was not involved in writing) in the manner of Anna Held, Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. As a character in the play she would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.

For this production, Max was teamed with Harry B. Smith provided the bulk of the lyrics, but Gertrude and Max wrote at least one piece together, On San Francisco Ban, their only know collaboration. Gertrude was somehow involved on stage during out-of-town previews. In a scene worthy of the storyline of the film 42nd Street, the lead performer became ill and Gertrude was brought in as a ringer. Performing the song I Just Can't Make My Eyes Behave (ironically the hit but the only one that Max was not involved in writing) in the manner of Anna Held, Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. As a character in the play she would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.

For this production, Max was teamed with Harry B. Smith provided the bulk of the lyrics, but Gertrude and Max wrote at least one piece together, On San Francisco Ban, their only know collaboration. Gertrude was somehow involved on stage during out-of-town previews. In a scene worthy of the storyline of the film 42nd Street, the lead performer became ill and Gertrude was brought in as a ringer. Performing the song I Just Can't Make My Eyes Behave (ironically the hit but the only one that Max was not involved in writing) in the manner of Anna Held, Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. As a character in the play she would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.

For this production, Max was teamed with Harry B. Smith provided the bulk of the lyrics, but Gertrude and Max wrote at least one piece together, On San Francisco Ban, their only know collaboration. Gertrude was somehow involved on stage during out-of-town previews. In a scene worthy of the storyline of the film 42nd Street, the lead performer became ill and Gertrude was brought in as a ringer. Performing the song I Just Can't Make My Eyes Behave (ironically the hit but the only one that Max was not involved in writing) in the manner of Anna Held, Gertrude elevated her status on Broadway by stealing the show. As a character in the play she would also dance with Held herself, although dressed in drag, shocking her audiences and many critics. The play overall seemed over the top for the time, featuring nude models on stage, and one critic even labeled it as "the most disgusting exhibition seen on Broadway this season." Despite, or perhaps because of this, the show saw a great success with over six months' worth of performances at the Broadway Theater, and helped to inspire the coming success of its producer.However, there was drama amidst the comedy, and Max became a key player. Hoffmann and Smith had been commissioned to write A Parisian Model by the Interstate Amusement Company, made up of several producers, including Ziegfeld. According to articles printed in the New York Sun and New York Tribune sold the proprietary rights of the play to them based on Hoffmann being retained as the musical director at a salary of $100 per week plus another $75 as a royalty. He also claimed that the conditions were that he would remain with the company for the entire season from November 1906 to late June 1907. However, he was notified on April 27, 1907, that the initial run would close on May 11, then continue with a different cast as a lighter-weight spring production until June 29, and that his services would no longer be needed. Max was displeased, and decided he would stand up for his rights in a unique manner. After the May 11 performance concluded he gathered up all copies of the score for both conductor and orchestra, and then left the building with them. Given that Max owned the copyright on the piece, the production company could not charge him with stealing his own material, so instead they lodged a larceny complaint against him for stealing the paper upon which it was written. He was arrested and arraigned the following week, and a judge then ruled that the production company was not able to substantiate the claim, so he was released. Max then applied for an injunction to prevent the play from further performances under the current circumstance, but was rebuffed by the court given that the producers were still going to pay him royalties. Despite the legal actions on both sides, neither Max or Gertrude's career was in no way derailed by the issues, and in the end all parties managed to work together, albeit with more detailed contracts. A Parisian Model was revived for a short run in January 1908, albeit without Max at the podium.

and that his services would no longer be needed. Max was displeased, and decided he would stand up for his rights in a unique manner. After the May 11 performance concluded he gathered up all copies of the score for both conductor and orchestra, and then left the building with them. Given that Max owned the copyright on the piece, the production company could not charge him with stealing his own material, so instead they lodged a larceny complaint against him for stealing the paper upon which it was written. He was arrested and arraigned the following week, and a judge then ruled that the production company was not able to substantiate the claim, so he was released. Max then applied for an injunction to prevent the play from further performances under the current circumstance, but was rebuffed by the court given that the producers were still going to pay him royalties. Despite the legal actions on both sides, neither Max or Gertrude's career was in no way derailed by the issues, and in the end all parties managed to work together, albeit with more detailed contracts. A Parisian Model was revived for a short run in January 1908, albeit without Max at the podium.

and that his services would no longer be needed. Max was displeased, and decided he would stand up for his rights in a unique manner. After the May 11 performance concluded he gathered up all copies of the score for both conductor and orchestra, and then left the building with them. Given that Max owned the copyright on the piece, the production company could not charge him with stealing his own material, so instead they lodged a larceny complaint against him for stealing the paper upon which it was written. He was arrested and arraigned the following week, and a judge then ruled that the production company was not able to substantiate the claim, so he was released. Max then applied for an injunction to prevent the play from further performances under the current circumstance, but was rebuffed by the court given that the producers were still going to pay him royalties. Despite the legal actions on both sides, neither Max or Gertrude's career was in no way derailed by the issues, and in the end all parties managed to work together, albeit with more detailed contracts. A Parisian Model was revived for a short run in January 1908, albeit without Max at the podium.

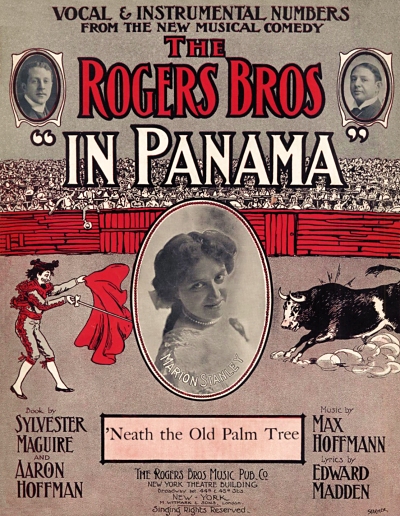

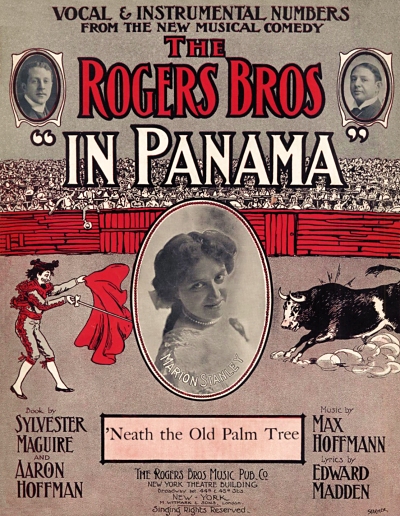

and that his services would no longer be needed. Max was displeased, and decided he would stand up for his rights in a unique manner. After the May 11 performance concluded he gathered up all copies of the score for both conductor and orchestra, and then left the building with them. Given that Max owned the copyright on the piece, the production company could not charge him with stealing his own material, so instead they lodged a larceny complaint against him for stealing the paper upon which it was written. He was arrested and arraigned the following week, and a judge then ruled that the production company was not able to substantiate the claim, so he was released. Max then applied for an injunction to prevent the play from further performances under the current circumstance, but was rebuffed by the court given that the producers were still going to pay him royalties. Despite the legal actions on both sides, neither Max or Gertrude's career was in no way derailed by the issues, and in the end all parties managed to work together, albeit with more detailed contracts. A Parisian Model was revived for a short run in January 1908, albeit without Max at the podium.Just two months later in early July, Ziegfeld staged the first of what would become over a quarter of a century of his famed Ziegfeld Follies, which involved both Gertrude and Max behind the scenes. Max was the musical director and a couple of his songs had been interpolated. At some point at least one of Gertrude and Vincent's songs had also been used, and she contributed to the ambitious choreography. While he was still conducting for Ziegfeld, Max was also working to musically send the Rogers Brothers to the exotic locale of Panama, which in some instances meant literally rewriting existing songs to fit the new destination. Debuting in September of 1907, this would be the last Rogers Brothers production as Gus Rogers would die in 1908. As for Max, he would have more involvement in the Ziegfeld Follies over the next few years as Gertrude found her own way as a free-lance dancer and choreographer on Broadway. Her most literally arresting act was yet to come, and he was part of the whole "sordid" affair.

Debuting in September of 1907, this would be the last Rogers Brothers production as Gus Rogers would die in 1908. As for Max, he would have more involvement in the Ziegfeld Follies over the next few years as Gertrude found her own way as a free-lance dancer and choreographer on Broadway. Her most literally arresting act was yet to come, and he was part of the whole "sordid" affair.

Debuting in September of 1907, this would be the last Rogers Brothers production as Gus Rogers would die in 1908. As for Max, he would have more involvement in the Ziegfeld Follies over the next few years as Gertrude found her own way as a free-lance dancer and choreographer on Broadway. Her most literally arresting act was yet to come, and he was part of the whole "sordid" affair.

Debuting in September of 1907, this would be the last Rogers Brothers production as Gus Rogers would die in 1908. As for Max, he would have more involvement in the Ziegfeld Follies over the next few years as Gertrude found her own way as a free-lance dancer and choreographer on Broadway. Her most literally arresting act was yet to come, and he was part of the whole "sordid" affair.When Richard Strauss first had his 1907 opera Salomé staged at the Metropolitan Opera, it was backed by J. Pierpont Morgan, William K. Vanderbilt and August Belmont, some of the richest men in the world. The story was so shocking that they ended up working to get it removed from the stage. So when Gertrude was offered the sketch A Vision of Salomé, she took the character to heart and strove to replicate her vision of the famed stepdaughter of the biblical Herod Antipas who was readily seduced by an over-the-top performance engineered to have her mother's wish fulfilled – that of delivering the head of John the Baptist. While that vision was disturbing enough in print, bringing it to life was too much for many. In fact, after the initial performance, New Yorkers flocked to the theaters in large numbers so they could be equally disgusted by Gertrude's sexually charged performance.

To learn the role and the dance, Gertrude actually went to London with Max under false pretenses, agreeing to a contract to work in a show with Maude Allan, who was doing a similar dance at that time. After about a day Gertrude figured out the general crux of the dance, then vacated the theater, sailing back to New York as quickly as possible, creating a legal issue for any future performances in London. Concerning the Strauss production on which Gertrude's performance was derived,

Theatre Magazine noted that the part that most "offended" the crowd was when the head was delivered and Salomé increased the erotic fervor with which she danced while kissing the head, something that "sickened the public stomach." Sam M'Kee of the New York Telegraph gave his own account:

|

Suddenly, she turns and sees the head of John the Baptist. She takes it with a combination of eagerness and aversion… places the head before her and in wild abandon, as if to conquer her loathing, begins a tempestuous dance. She is garbed with draperies and gewgaws of a bloody age… but the effect is that she is naked.

Perhaps Gertrude was simply too seductive. Efforts to stop the show did nothing but publicize the staged atrocity, which went on to shock audiences in other cities around the East, even resulting in the occasional arrest or performance canceled by a local judge. There has long been speculation that some of these arrests were staged for publicity purposes, although little evidence has been found to either support or deny such charges, which nonetheless ring true. Gertrude would dance other erotic roles in scanty clothing that resulted in the same result over the next few years – selling tickets to a public willing to have their Victorian morals shocked senseless. She was not the only stage persona to bring a salacious Salomé, some suggesting that dancer Ruth St. Denis' was "out-Saloméing all the Salomés." But Gertrude was still one of the most memorable. She even had reportedly her extremities insured for $2500 per week at one point – or at least a story was leaked that she did – in case anything was damaged and she could not perform. Whether the costs of the arrests were covered by insurance is unknown. Max provided a score for Vision of Salomé for its run starting at the Hammerstein Theatre's Roof Garden, and critic, in attempt to be clever, noted that his "music for the act was vague and blue. Get that? Vague and blue."

She was not the only stage persona to bring a salacious Salomé, some suggesting that dancer Ruth St. Denis' was "out-Saloméing all the Salomés." But Gertrude was still one of the most memorable. She even had reportedly her extremities insured for $2500 per week at one point – or at least a story was leaked that she did – in case anything was damaged and she could not perform. Whether the costs of the arrests were covered by insurance is unknown. Max provided a score for Vision of Salomé for its run starting at the Hammerstein Theatre's Roof Garden, and critic, in attempt to be clever, noted that his "music for the act was vague and blue. Get that? Vague and blue."

She was not the only stage persona to bring a salacious Salomé, some suggesting that dancer Ruth St. Denis' was "out-Saloméing all the Salomés." But Gertrude was still one of the most memorable. She even had reportedly her extremities insured for $2500 per week at one point – or at least a story was leaked that she did – in case anything was damaged and she could not perform. Whether the costs of the arrests were covered by insurance is unknown. Max provided a score for Vision of Salomé for its run starting at the Hammerstein Theatre's Roof Garden, and critic, in attempt to be clever, noted that his "music for the act was vague and blue. Get that? Vague and blue."

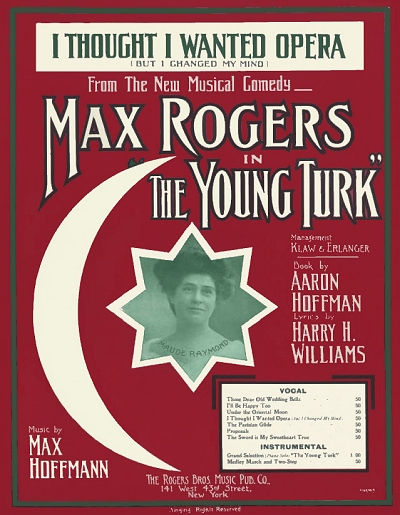

She was not the only stage persona to bring a salacious Salomé, some suggesting that dancer Ruth St. Denis' was "out-Saloméing all the Salomés." But Gertrude was still one of the most memorable. She even had reportedly her extremities insured for $2500 per week at one point – or at least a story was leaked that she did – in case anything was damaged and she could not perform. Whether the costs of the arrests were covered by insurance is unknown. Max provided a score for Vision of Salomé for its run starting at the Hammerstein Theatre's Roof Garden, and critic, in attempt to be clever, noted that his "music for the act was vague and blue. Get that? Vague and blue."With Gus Rogers now gone, his brother Max Rogers, whom many critics commented was perhaps the more talented sibling, tried to move forward with a property of his own. He chose The Young Turk for the late fall of 1909, which did not debut on Broadway until early 1910. Max wrote the entire score to lyrics by Harry H. Williams and a book by Aaron Hoffman, who had also contributed lyrics to a number of Broadway plays since 1905, and other books for the Rogers Brothers. While this raises the question of family ties, Aaron was a native of Saint Louis, Missouri, so his association with Max was merely once of happenstance. Unfortunately for Rogers The Young Turk never really took off, closing after 32 performances to lackluster reviews. One even went after the composer, stating that "None of Max Hoffman's musical numbers showed much originality, although two of them are easy to carry away." After a couple more short stints on Broadway, Max Rogers would drop out of the business around 1914.

Continuing to provide choreography services to Ziegfeld and Hammerstein, Gertrude tried to elevate the level of serious dance as well. Building on her fame as Salomé, she further created dances based on other historic seductive women, including Cleopatra of Egypt and Scheherazade of 101 Arabian Nights lore. In 1911 Gertrude brought part of the famed La Saison des Ballet Russes (Session of Russian Ballets) to New York. For the event, Max conducted a 75 piece symphonic orchestra. In addition to dancing, she also became a reasonably good mimic on stage at Hammerstein's Roof Garden of other famous personalities ranging from the equally sultry Eva Tanguay to British music hall singer Vesta Victoria, and even the foppish comic with the large family, Eddie Foy. Max was there in many cases providing musical leadership or input for her act. The 1910 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed Max as a theatrical musician and Gertrude as a theatrical actress, with three years trimmed off her age for good measure.

The 1910 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed Max as a theatrical musician and Gertrude as a theatrical actress, with three years trimmed off her age for good measure.

The 1910 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed Max as a theatrical musician and Gertrude as a theatrical actress, with three years trimmed off her age for good measure.

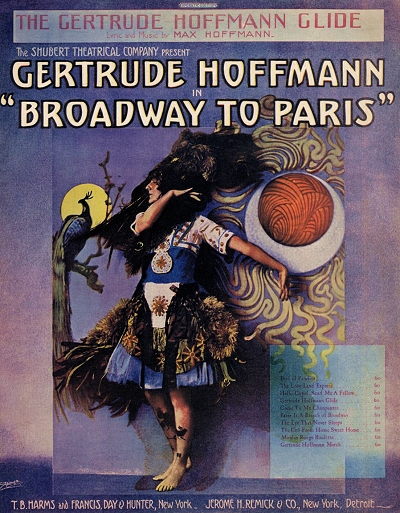

The 1910 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed Max as a theatrical musician and Gertrude as a theatrical actress, with three years trimmed off her age for good measure.While Gertrude appears to have all but quit composing after 1911, it is notable that she became famous for a piece composed by her husband, The Gertrude Hoffmann Glide, to which she had a dance routine in the 1912 show From Broadway to Paris at the Winter Garden Theater follwing a run in Boston. Its popularity in both sheet music and recorded form helped to further spread her name and fame around the country. The show itself, which following previews in Boston initially ran from November 1912 to late January 1913, was well received by the critics. As one of them noted:

Anything like remotely intellectual purpose… was made subordinate to what should delight the eye and the ear…

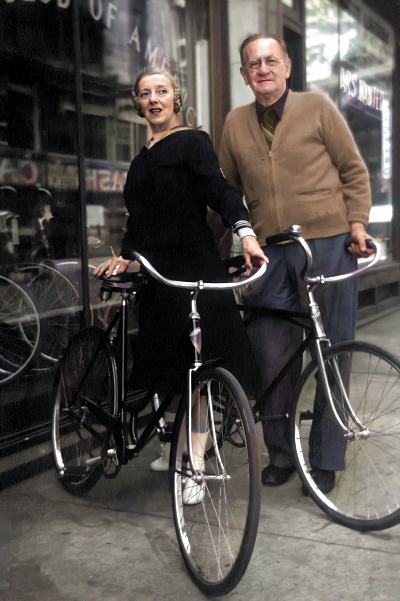

Gertrude Hoffmann, who has added bicycle riding to her other arts, capered through a dance called "The Garden of Girls," which was mythological and poetic and on the plan of the spring dance she used to do in the vaudeville theatres. Then she did some of her imitations. She wore her extravagant dresses that gave her the look of one those that have feathers and bite and sang in a childish treble.

After her run of the show on Broadway, Gertrude planned to tour in her own act. One of the venues she booked was Alexandra Theater in Toronto, Canada, but according to The New York Clipper of March 29, 1913 she was barred from presenting her act as the theatrical censor of the city "saw it in the United States." From August through October 1913, the Hoffmanns embarked on a national tour with French singer Émilie Marie Bouchad (a.k.a. Mlle. Polaire) and British dancer Lady Constance Stewart-Richardson, each of them bringing along their own music directors as well, and presenting art song and dance, ending in New York City.

Gertrude then took her own revue on a national tour through the end of the year. In advertising for talent for her show, she noted that they should be girls 16-18 years old, experience not necessary, and a pretty face and figure were the only requirements. This was the beginning of what would become the famous Gertrude Hoffmann Girls. The opening week was popular enough that it created a dangerous situation at The Playhouse in Wilmington, Deleware, where it was staged. The crowd on Monday night, November 3, 1913, was so great that some people were nearly crushed when the house was opened, and a railing on one of the stairways gave way, sending several customers as much as ten feet down to the floor. Several hundred potential audience members were left out in the cold as all seats were sold and the standing room only section filled immediately. The show received a glowing review, including for the orchestra led by Max.

Mr. Hoffmann, who had helped with Gertrude's career when they first met, had trusted it now for some time to Morris Gest, but Gest gave up that role "in despair" when he was unable to keep that ball rolling due to Mrs. Richardson and Mlle. Polaire objecting to Gertrude's near nudity on stage and other errant behaviors. So for a time, Gertrude was facilitating her own booking work and Max found some other work. However, in the Spring of 1914 the large United Booking office took over the duties, leaving her free to perform and develop new acts. Max also made a big move, becoming a naturalized American citizen on June 23, 1914.

Gertrude spent a second year absent from Broadway stage shows, instead playing the bigger vaudeville houses, like the Colonial, B.F. Keith’s, and even the storied Palace in Manhattan. Just the same, the Hoffmanns were encountering the occasional boycott when on the road, often from religious groups that found the tone of Gertrude's act objectionable, and were able to persuade locals to avoid going to her shows, which she had to cancel from time to time. Yet some reviewers insisted that her revue had a lot of merit and that she entertained "without offense." When he was not engaged with other shows, Max traveled with his wife to conduct the orchestra. Yet they still found some time during an occasional hiatus to relax in their Manhattan home, and even participate now and then in local community activities, often as the guests of honor.

The 1915 New York census echoed the 1910 record, showing that the Hoffmanns also had two live-in domestics, necessary to help take care of Max, Jr., who was now in his early teens. It would be another busy year for Gertrude and Max. In addition to her own 1915 Revue, which toured into the spring, she was featured in a "vaudevilleized" version of the Max Reinhardt German play Sumurun (sometimes referred to as One Arabian Night), a "wordless play" that had originally opened on Broadway in 1912. It ran at the Palace for at least part of the summer, followed by B.F. Keith's, and then the Orpheum in Brooklyn that fall. This now-famous pantomime featured Gertrude in the title role of a sheik's main slave girl in love with another man, so seductive dancing was clearly involved. There was even a water tank on stage used for a salacious bathing scene involving a bevy of beautiful harem girls. Max was at the podium as well, providing appropriate music for the pantomime, and both Hoffmanns received positive reviews.

When not supporting his wife through either touring with her or providing musical support, Max, who appears to have quit composing material for publication in the early 1910s, was still viable as a musical director in New York. In 1916 he was hired as the orchestral leader at the Century Theatre in New York. Among the shows at which he took the helm in the orchestra pit were The Century Girl in late 1916 featuring music by Irving Berlin, Victor Herbert and L. Wolfe Gilbert and the popular Dance and Grow Thin in early 1917, with music by Berlin, George W. Meyer, and newcomer Blanche Merrill.

At the same time, Gertrude was contemplating going into motion pictures. Her asking price was reportedly $40,000 per feature. This clearly was high by film actor standards of that time, and as a result she apparently was never in a film—at least none that are extant or documented. Following a late winter tour she enjoyed a revival of Sumurun in the spring, then got a regular gig at the recently opened Cocoanut Grove venue on the roof of the Century Theatre. She also appeared in the musical Dance and Grow Thin in the theater downstairs, which was led by Max. The Hoffmanns provided a variety of stage fare for both into early 1917, after which they abandoned their posts for new horizons. The first of those was the Gertrude Hoffmann 1917 Revue, which played throughout the spring.

|

World War I was problematic for the entire country, and Broadway and the music world were hit relatively hard as many men were drafted, and some would never return. Through enlistment and draft, Gertrude lost six successive dancing partners in 1916 and 1917. Near the end of the war, many members of the Broadway community were stricken by the Spanish Flu pandemic, which caused the deaths of some of them. To fill in the gap, Gertrude called on her son, Max. Jr., to become her next partner. He had just entered Cornell to pursue a course of study in civil engineering, but Gertrude was desperate, and audiences still were looking for entertainment to forget their woes of the time. Playing in her Revue at the Winter Garden Theater in late 1917, the 16-year-old was evidently up to the task, and smitten by the allure of the stage, quickly become quite adept at both dancing and acting. After a full season he went back to Cornell to finish his degree. Around that same time in the summer of 1918 Max and Gertrude moved into their new custom-built home at Sea Gate on Coney Island.

Touring the country during the early days of World War I, Gertrude and her husband continued to make the headlines now and then for supposedly scandalous behavior. Even as late as 1917 as public morals and fashion trends were evolving, her stage outfits still caused problems for some of the community gatekeepers for public decency. She had upped the ante a bit not only in trimming down her wardrobe for 1918, but now dancing with snakes as well in her Revue for that year. In early December 1918, Gertrude and Max were called into the courtroom in Saint Louis, Missouri, where he assured the judge that even as Salomé she was wearing three layers of tights reaching down to her knees. Two weeks later on Christmas Eve, Max and two others from the company were hauled in front of a magistrate in Omaha, Nebraska, which was a dry state, on the charge of having transported liquor there in the form of wine and champagne from Kansas City, Missouri. Max was later acquitted based on the premise that his car was his home while traveling, and produced a telegram from Gertrude's doctor claiming, thinly, that "champagne was necessary to the health of the star."

Throughout the late 1910s Gertrude pulled in more credits for her work on stage and behind the scenes, mostly with large ensembles in revues or revivals. However, around the time the war ended she made the choice to work as a single - just Gertrude and a small orchestra with no major supporting players. So for part of 1919 she and Max traveled the United States, including longer stints in Chicago, Buffalo and Philadelphia, providing a high-class solo act that was typically courteously reviewed, if not enthusiastically. A smaller-scale tour was undertaken in early 1920, followed by a similar itinerary in 1921, one that introduced her exotic “White Peacock” interpretation. Just the same, now in her late thirties, Mrs. Hoffmann’s reputation remained intact in a number of ways, as evidenced by this colorful Chicago Tribune review of November 3, 1921:

MISS GERTRUDE HOFFMANN is at the Majestic again, with her Madonna countenance and her wicked ways, dancing as serenely as ever through the most disturbing of choreographic incidents. No one can denote a mood of abandoned devilry and be as prim about it as she… It is outré and decadent and I suppose I should know what it is all about… And, as always, the fatherly, gray haired Max Hoffmann sits at the piano, getting more blare and infectious rhythm out of his little band of musicians than most conductors can get from a full orchestra.

The Volstead Act of 1919 which spurred the National Prohibition of alcohol starting in 1920 was not kind to vaudeville, an entertainment that, by that time, arguably required a bit of lubrication to enhance the experience. It was much easier to serve up jazz in a speakeasy than it was to dispense illegal liquor in a loosely-formatted theater. So, the postwar full Broadway shows and revues tended to lure the better writers and musicians, while vaudeville houses started to empty. This worked for Max who was both valuable flexible in this regard. However, despite Gertrude's talent, beauty and history, at that time it was a lot to ask people anywhere in the country to come watch a 37-year-old solo dancer with only moderate comedic and singing skills in a sparsely populated venue. By this time, Gertrude was doing less on stage and Max was performing more in front of it.

When he was not touring with Gertrude he continued to find favor as a musical director and arranger, and in late 1920 was responsible for the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic on the roof of the New Amsterdam Theatre. Some of the incidental music was provided by himself, in addition to songs by Harry Carroll, Harry Akst and Irving Berlin. It was followed by the mid-season Nine O'clock Frolic in February 1921. There are suggestions in various papers that he provided some of the musical content for this as well, particularly for a tableau titled Paris, 1793, Place de la Revolution. However, there was nothing in the form of publishable songs from either show.

In 1923, Max opened his own conservatory of music in Freeport, Long Island, with the following announcement within the advertisement that also touted his own orchestra:

MAX HOFFMAN CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC…

HOWARD BLACKMORE, Associate Director…

Instruction on all instruments, theory, composition, harmony and orchestration, under the personal supervision of Max Hoffmann, formerly solo violinist Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, composer and director for Gertrude Hoffmann's attractions, Ziegfeld Follies, Klaw, Erlanger and Dillingham productions, New York Winter Garden, Russian Ballet, etc…

MAX HOFFMAN'S ORCHESTRA

A permanent organization of recognized artists under the personal leadership of Max Hoffmann.

Gertrude, finding less opportunity for bookings, was still active and restless, feeling a continuing need to contribute to the stage and the art of dance. This dilemma led to the formation of her own pre-Rockettes chorus line, the highly athletic Gertrude Hoffmann Girls.

It was more of an evolution than a formation. They were first mentioned as her all-American ballet troupe of sixteen girls in late 1921 as part of her current traveling show.

|

That group would grow in its fame and repertoire in the early to mid-1920s, becoming the Gertrude Hoffmann Girls in 1924. Make no mistake that Gertrude was in the middle of it all, appearing on stage with her bevy of beauties. They were part of at least two tours of Europe which included appearances at the Moulin Rouge in Paris and the Hippodrome in London in both 1924 and 1925, and both trips included Max in some capacity, most likely as their traveling conductor and music director. The following season they played at the Winter Garden Theater in Manhattan in Artists and Models, a Shubert production. Gertrude and her girls danced for two more consecutive seasons at the Winter Garden in 1926 and 1927 in A Night in Paris and A Night in Spain. It is curious, then, that for the 1925 New York census, Gertrude was shown as a housewife, while her husband and a lodger in the home were both listed as musicians.

Meanwhile, Max, Jr., was working the stage as well. Although he had finished his studies at Cornell, his earlier encounter with the stage was too enticing, and he set out attempt a career in show business despite his mother's protestations. While she was in Paris with her troupe, he went around to several casting offices in pursuit of a role. After having appeared in 1922 in a production featuring Nora Bayes at the George M. Cohan theater, He would continue to work his way up through the ranks, including dancing with Ann Pennington in Jack and Jill in 1923, earning his own measure of fame, but not without many public hiccups. Among those was the first of two failed marriages, this one with actress Norma Allison, who was also known as Norma Terris. She had worked with the younger Max in vaudeville before gaining fame in Ziegfeld's production of Showboat in the role of Magnolia, and they co-starred in A Night in Paris as well, making the show a true Hoffmann family affair. But by the late 1920s the couple would be split. He had also been put in charge of one unit of the Gertrude Hoffmann Girls in 1925, which may have been a risky endeavor.

In the spring of 1925, Max and Gertrude ventured again to Europe to celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary, albeit a year early. Upon returning to New York in late May, they held a celebration, and Gertrude commented on the state of their union:

…money, jewels, automobiles and expensive living do not bring happiness or make for a happily married life. Real happiness must come from within. As to growing old—well, if people dwelt not on the subject they could remain young. Pass from one stage of life to the next cheerfully and buoyantly and old age will be long in coming.

|

The 1930s are a little vague for information on the couple. Max got some work arranging and writing for movies, which required the occasional stay in Hollywood, but the Hoffmanns still maintained their Long Island home, and Gertrude was working behind the scenes in both New York and Europe. She also attempted a couple of comebacks in 1933 and 1935, backed by her girls, but they were short-lived. Max was now doing less conducting and arranging, even for his wife, and would soon ply his trade as a violinist playing in some Broadway pit orchestras.

Max, Jr., made the news again in a rather ignominious fashion. Questionably a playboy of sorts, in February 1933, he married singer Helen Kane, known both for her late 1920s songs and for inspiring and voicing the cartoon character Betty Boop. Kane was also appearing in the musical play Shady Lady that year, which featured Max, Sr., leading the orchestra one last time, and his son as one of the leads in the production. It appears that around six months after the nuptials he forgot he was married and simply took off, forcing Kane to file for a divorce that was finalized in 1935. It was not the type of publicity the family might have hoped for. By then, he was working in California in motion pictures, and would soon marry again, this time to Luana J. Walters, also an actress.

|

After 1940 little was heard concerning Gertrude or Max, who ostensibly retired. Their son's lifestyle eventually caught up with him, and Max Hoffmann, Jr., died in March 1945 in Manhattan at age 43 of a reported stomach ailment. At that same time, it was reported that the senior Max was part of the pit orchestra as a violinist for the ongoing run of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma, the show that largely changed the direction of Broadway pretty far from the institution in which he had started and helped to form. The Hoffmanns permanently relocated to Los Angeles, California, in the early 1950s, taking up residence in West Hollywood in the luxurious Fleur de Lis Apartments. Max died there in May of 1963 at age 89, followed by Gertrude in 1966 at age 83. Both were interred at Grand View Memorial Park and Crematory in Glendale, California.

This article was largely derived from public records and newspaper notices, literally over 1000 of them, contemporary to the lives of the Hoffmanns. Some additional information came from copyright records, IBDB.com and IMDB.com, as well as the always reliable reference source, Vaudeville Old and New, by Frank Cullen, Florence Hackman and Donald McNeilly. The NYPL was a good source for photographs and articles on Gertrude. Many of Max Hoffmann's manuscripts, not all listed above, can be viewed online at Max and Gertrude Hoffmann Music Manuscript Collection courtesy of Wake Forest University.

Compositions

Compositions