May Irwin was born as Georgina May Campbell (Ada has often been cited but can be brought into question as it is likely her sister Adeline's nick name). While 1862 has often been her accepted birth year, her birth record and her age in various census records, starting in 1871 and continuing to 1930, is consistent with an 1861 birth year, which is likely the most correct. A native of Whitby, Ontario, Canada, her parents were Scottish immigrants (often shown in census records as Canadians) Robert E. Campbell and Sophronia Jane (Draper) Campbell. Georgina May was raised in her first years in Whitby, Ontario, around 35 miles northeast of Toronto.  She was the last of five surviving children, including Chester (1852), Franklin (1854), Albert (1856), and Adeline Flora (2/8/1859). Robert was listed as an agent of some kind in the 1861 Canadian census, and as a clerk in the 1871 census, along with his oldest son working in the same position. May later said he was a lumber dealer.

She was the last of five surviving children, including Chester (1852), Franklin (1854), Albert (1856), and Adeline Flora (2/8/1859). Robert was listed as an agent of some kind in the 1861 Canadian census, and as a clerk in the 1871 census, along with his oldest son working in the same position. May later said he was a lumber dealer.

She was the last of five surviving children, including Chester (1852), Franklin (1854), Albert (1856), and Adeline Flora (2/8/1859). Robert was listed as an agent of some kind in the 1861 Canadian census, and as a clerk in the 1871 census, along with his oldest son working in the same position. May later said he was a lumber dealer.

She was the last of five surviving children, including Chester (1852), Franklin (1854), Albert (1856), and Adeline Flora (2/8/1859). Robert was listed as an agent of some kind in the 1861 Canadian census, and as a clerk in the 1871 census, along with his oldest son working in the same position. May later said he was a lumber dealer.While she and her sister were attending a convent school in late 1872, Robert fell ill and died, leaving his widow and four remaining children to fend for themselves. In need of funds to survive, Jane decided to leverage Georgina May's talent and potential as a singer and actress, convincing Florence to also give stage performance a try. May had aspirations to be a nurse, but it was clear that this was the more economical way to go.

The first American audition of the Campbell sisters took place in Buffalo, New York at the Adelphi Theatre in December of 1874. It was reported that Florence fainted after their number due to the stress of the situation, but May, at all of thirteen and a half-years-old, came back with an encore that secured them a job. There is some variance as to whether May made her professional debut as a soloist on a stage in Rochester or with Florence in Buffalo, but both of these events potentially occurred in early 1875. Early in their career a theatrical agent name Daniel Shelby took on representation of the act. He claims to have given the girls the names of May and Florence to replace their current names of Georgina and Ada, but there is some doubt to this story as both are part of their middle names. It is, however, possible that Shelby gave them their new last name of Irwin, which both kept to the end of their respective professional careers.

Playing vaudeville stages in the Northeast over the next two and a half years, the sisters were finally booked at the Metropolitan Theater in New York City, which led to a series of bookings at Tony Pastor's famous music hall, where many vaudeville stars quickly rose to fame or sank to ruin. Pastor knew show business and he knew talent, fostering it whenever he could. He was able to infuse many values of showmanship into the sisters, including stage presence and comic timing. This served May well when she finally struck out on her own a few years later.

It was in New York that May met Frederick W. Keller (may also be W. Frederick Keller), a treasurer at one of the Manhattan theaters (it may have been Pastors, but this has been difficult to pin down). They married in 1878 and settled in Manhattan. Even though May and Flo were still performing on a regular basis, she is listed in the 1880 census as a housekeeper, staying home with their infant son Walter, the first of two children the couple had. . It could be assumed that May was on a temporary hiatus following childbirth. Their second son Harry Campbell was born August 28, 1881.

It was either late 1883 or early 1884 that May received an offer from producer Augustine Daly to join his traveling stock company.  Either Flo was not included in this offer or she declined it. May did accept it and the sister act was split up, making May Irwin a soloist. She is shown traveling in 1884 on the S.S. Arizona for London with the company, listed as Miss May Irwin. It was on that trip that she made her London debut at Toole's Theatre in August of 1884.

Either Flo was not included in this offer or she declined it. May did accept it and the sister act was split up, making May Irwin a soloist. She is shown traveling in 1884 on the S.S. Arizona for London with the company, listed as Miss May Irwin. It was on that trip that she made her London debut at Toole's Theatre in August of 1884.

Either Flo was not included in this offer or she declined it. May did accept it and the sister act was split up, making May Irwin a soloist. She is shown traveling in 1884 on the S.S. Arizona for London with the company, listed as Miss May Irwin. It was on that trip that she made her London debut at Toole's Theatre in August of 1884.

Either Flo was not included in this offer or she declined it. May did accept it and the sister act was split up, making May Irwin a soloist. She is shown traveling in 1884 on the S.S. Arizona for London with the company, listed as Miss May Irwin. It was on that trip that she made her London debut at Toole's Theatre in August of 1884.In 1886 Frederick, close to two decades older than May, died after eight years of marriage, leaving her as a widowed single mother. After a short break she managed to find a way to manage both children and show business, her only source of income, and continued her climb to fame on stages in New York city and around the east coast. At some point in 1888 she received an offer from Howard Athenaeum in Boston that raised her standard of living considerably. One play in late 1888 was Home Rule which briefly reunited her with Flo. Howard was able to find productions that best suited May's comedic talents and unique singing style.

While May appeared frequently in farces, some of the songs were simply interpolated popular favorites or new pieces, often having little to do with the plot. However, her growing fame in Boston increased the demand for the comic songstress back in Manhattan, and she returned in the early 1890s. In 1892 she once again hit the boards with Flo in the touring stage comedy Boys and Girls, the very first play she had done with Daly a few years prior, but in a better role.

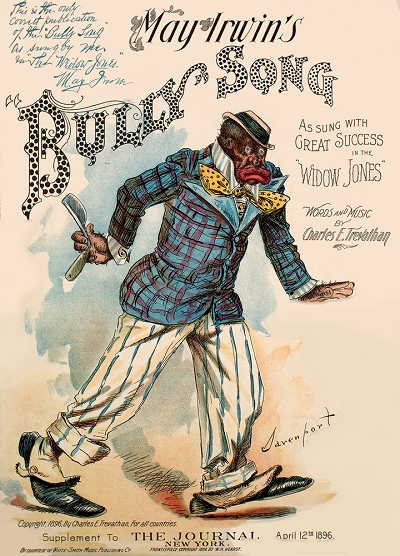

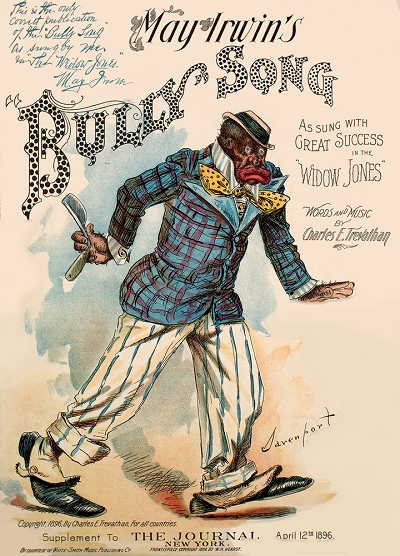

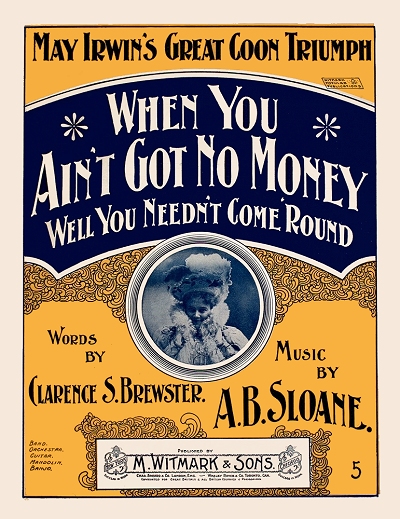

Back in New York City, May developed her act into a genre known as "coon shouting," performing comic songs influenced by stereotypes of African Americans. During her travels she met a sportswriter that would eventually make her famous. In 1893, her current manager, Charles Frohman, got May a spot touring with the cast of The Country Sport, headed by Pete Dailey who had been engaged by the famous Weber and Fields. While they were in the western United States, she met Charles E. Trevathan, a sports reporter from the South. He joined the cast during a multi-day train ride back East in their parlor car while everybody told stories or sang songs. Trevathan had a guitar along and played on particular melody that attracted May's attention. She suggested that he put lyrics to it. Not long after that while the troupe was performing in Chicago, Trevathan came to the theater with a set of lyrics for the tune. May asked the musical director to arrange it, and soon after she started to sing The Bully Song, but not as part of the show.

By 1895, after having spent some time touring with Dailey in a couple of other shows, May wanted to stay put. She won the starring role in a musical comedy called The Widow Jones which after brief tryouts in Brockton, New Bedford and Boston opened on Broadway on September 16, 1895 at the Bijou Theater. Included in the play, at her insistence, was The Bully Song. It was what might be described as a "coon song" like those she had become known for. Unlike other women stars of the time who sang similar material in blackface, May preferred to just let the song sell itself through her performance. The ploy worked, and both The Widow Jones and The Bully Song received great attention after their Manhattan debut.

Not only was the piece a hit, printed as May Irwin's Bully Song (even though she did not receive composer credit), May became a bigger star almost instantly. She was also very protective of her new signature song, being the copyright owner. In a warning issued in the trades in 1896:

The White-Smith Music Publishing Co. have issued a notice to dealers warning them against unauthorized versions of the 'Bully' song written [sic] and sung by May Irwin, which will soon be published by this house. Miss Irwin, in a recent communication to the White-Smith Music Publishing Co., says: 'It is solely and absolutely my property; no other publisher has a right to use it.'

|

As a result of her meteoric rise in popularity, May became one of the first movie stars as well. In the play was a particularly sensuous (for that time) kiss between Irwin and her co-star John C. Rice. Thomas Edison allegedly saw the show and quickly realized that this would make for a sensational film scene. In 1896, most "movies" consisted of snippets from 30 seconds to 3 minutes long, and virtually anything captured moving was considered film-worthy. Whether Edison really considered this independently or not is uncertain. The more likely story told is that the idea of staging the kiss for such a film was brought to Edison by the New York World newspaper. As a result, this very short subject, 42 feet of film shot in April of 1896 in Edison's Black Maria studio became one of his best known early Kinetoscope productions. Titled The Kiss, the first such known kiss in the history of cinema, it became well known both for Irwin and for the scandalous notion that such a thing should not only be filmed but shown in public. Editorials railed against it and preachers lambasted it, which probably made it even more of a must see event. All of 21 seconds long, a few seconds of it comprising the actual kiss, the film was great publicity for both the star and the show.

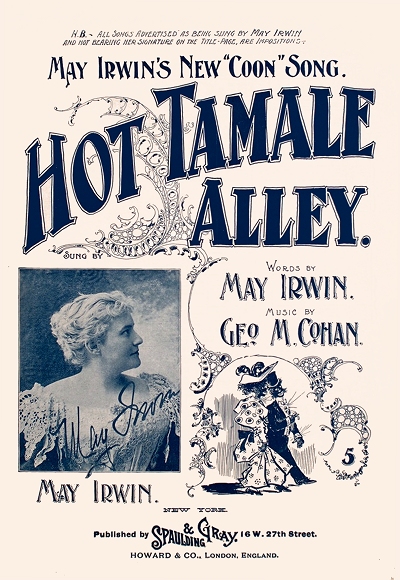

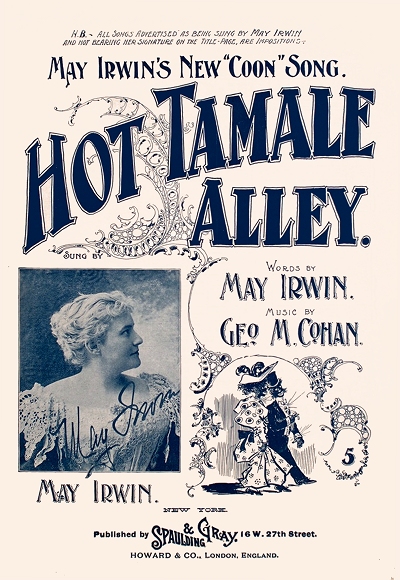

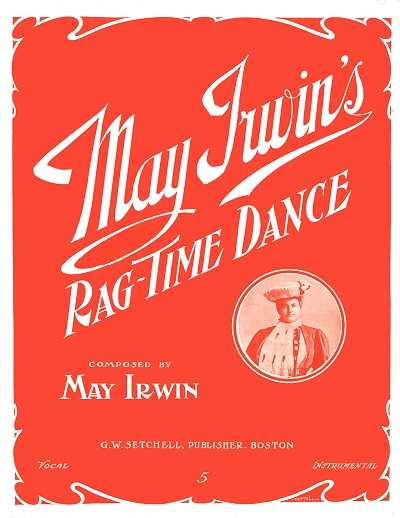

By mid-1896 the lifestyle of a star who ate well had changed Irwin's figure a bit as she had gained several pounds since her appearances in the early 1890s. Yet she still insisted on doing high stepping dances, including the cakewalk, singing out loudly for all in the theater to hear her in spite of restrictive corsets. Her popularity actually helped make such figures in vogue by the turn of the century. Within a few years May was lauded by many titles including the "Dean of Comediennes", "the Funniest Stage Woman in America", and even "Madame Laughter." In the years directly after The Bully Song became a hit, she co-wrote some of her own pieces, including one titled Hot Tamale Alley with rising star George M. Cohan. Trevathan wrote a follow-up to the Bully Song called May Irwin's Frog Song, introduced in 1896. Both Bully and Frog would remain with May throughout the bulk of career, even when she wanted to shake them from time to time.

A New York Times article from February 5, 1897, gives a slice of how Irwin was viewed during this busy period of her fame. It talks about a charitable appearance at the Colored Home and Hospital at First Avenue and 65th Street in Manhattan the previous afternoon. The reporter wrote:

"...and for an hour an uproarious audience enjoyed the fun. There was enthusiasm enough to stock many colored camp meetings every time the actress sang one of her Negro songs... Miss Irwin's jolly face beamed all over as she came to the front and met a storm of greetings. She began with Crappy Dan. The colored listeners had their eyes riveted on her, and their lips followed her words while they swayed in time with the music and broke out hilariously at the familiar ideas she express. The men especially were interested and were caught when the actress came to the lines: 'De wasn't no niggah dat eber frowed six But know I had 'im beat.' The men appeared chiefly uproarious, however, over the confidential information that 'wid a little bit o' lead de dice allus comes seven.' ...No house that Miss Irwin ever had had keyed her up to a higher pitch of enthusiasm. The sympathetic faces, the hearty laughter, the rhythmic swaying of the bodies seemed to inspire her. When she was through the audience wanted more, but she had to go. She held a levee and many wistfully asked: 'Ain't you gwine come no mo'?' She promised she would.

The high profile actress was also subject to controversy from time to time, but it usually did not seem to result overtly in negative press. Concerning a potential lawsuit in late 1899, the following appeared in The Music Trade Review of November 4:

There is trouble brewing around Koster & Bial's and the Bijou, and all about a song. It is called "What Did Mary Do? " and is sung by May Irwin in "Sister Mary." She says the words were written by Louis Harrison and the music by Fred Solomon. William A. Brady claims it was stolen from "Mary Was a House Maid "in " Pot Pourri," a London burlesque which he has bought for America and will use at Koster & Bial's. He says that he gave Miss Irwin and Mr. Sire, manager of the Bijou, warning that he owned the sole rights to the song for this country. Miss Irwin is singing it every night, however, as usual. Brady says that he will get out a warrant for the arrest of Mr. Sire. Miss Irwin and Mr. Sire's side of the case is that though it may resemble the English song it was written by Mr. Harrison and Mr. Solomon.

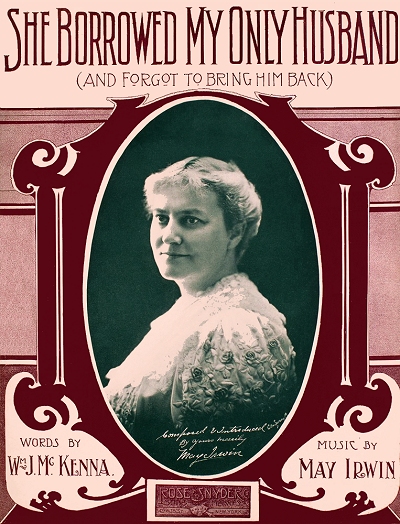

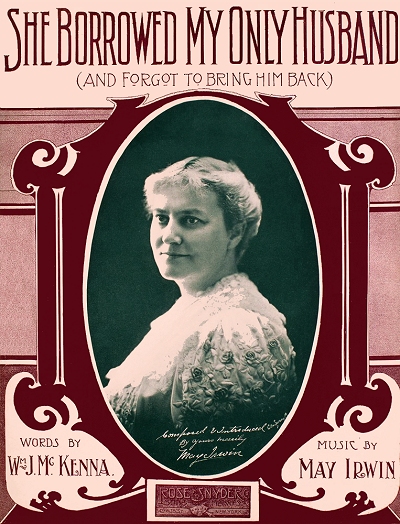

May's residence status in 1900 was uncertain as she was not found in the census for that year, possibly on tour when it was taken. Around that same year she helped to revive the first million seller song, After the Ball, with her own unique performances of the piece. After the Widow Jones she starred in at least a dozen other productions. None of them were very successful or garnered much interest other than Irwin's involvement, which most often meant singing interpolated coon songs, including the ones she was most famous for. In spite of the failure of some productions, May was a shrewd investor who took her high paying salary and turned it into somewhat of a fortune in stocks and real estate. Among these acquisitions was a full block of Manhattan on Lexington Avenue between East 53rd and 54th Streets, which she sold for a substantial sum in the early 1930s. She even wrote a cookbook, May Irwin's Home Cooking "Like Mother Used to Make", published in 1904.

Sometime in the early 1900s, and perhaps before, she met a theatrical agent from Lynnfield, Massachusetts named Kurt V, Eisfeldt (often misattributed as Eisenfeldt). Kurt had emigrated to the Boston, Massachusetts area from Austria at the age of three in 1876 with his parents, and was nearly 12 years May's junior. In short order he became her personal agent, and by 1907 her husband.

At that same time May entered another facet of the growing entertainment industry, recording a few sides for the Berliner and Victor record labels. The actress had reportedly recorded a couple of cylinders for Columbia in the late 1890s, which are difficult to locate today. She did record seven of her most popular tunes for Victor in the spring of 1907, six of which were released, all selling fairly well. Many of the recordings have survived over the past century, and can give some idea of the appeal of May Irwin through her vocal performance, even if it lacks the visual element that was part of the overall package.

Throughout much of her career following The Widow Jones Irwin became known as both generous and fierce. She was clearly a force to be reckoned with, and whenever possible became her own producer so she had more creative control over the shows she was in. Yet she also did many charitable appearances as well, and advocated for a number of causes. One of those was the humane treatment of animals. There was one vaudeville showman named Mr. Galeman who mercilessly beat animals on stage as part of his act. Once Irwin was alerted to this, she used her considerable power to have Galeman chased not only off of the stage, but out of the United States.

May's success with audiences over the years also translated into many within the theatrical community to look to Miss Irwin for advice. In a Music Trade Review article printed November 17, 1906, she offered the following on the selection of pieces. Please note that Miss Irwin was fortunately far off base on the topic of the perpetual popularity of the 'coon song,' but her quote is included here for context.

May Irwin, now playing "Mrs. Wilson-Andrews" at her own theater, the Bijou, New York has an interesting interview on the selection of songs in the Evening World. On this subject she is considered something of an authority by publishers, as follows: "Picking out wall papers is almost as hard as picking out a song," sighed Miss Irwin. "A really good song is written once in ten years, and only one in ten thousand is good for anything. You've no idea of the number of utterly worthless songs that are turned out these days. Not that they're worse, on the whole, than the songs of other days. But there are so many of them that the public has become surfeited. Most of the songs that we get today are machine-made, and that is why we are so sick of them. They're manufactured wholesale on the same pattern, and you can hardly tell one from the other.

"It is only now and then we get a song with individuality or originality. 'Moses Andrew Jackson' has individuality—genuine humor and a swing to it. A great deal, of course, depends on the singer. There's 'Bill Simmons,' for instance. The fame of that song reached me at my home in the Thousand Islands last summer, and I asked one of my sons to bring a record of it for the phonograph. When I heard it on the phonograph I couldn't understand how it had made such a hit. But when I came to town and heard Maude Raymond sing it, I understood why it was so popular. It was the way she sang it. She made you see and feel 'Bill Simmons.' I almost fell out of the box with laughter. She put character into the song; that was the secret of her success.

"I always approach a song with fear and trembling. Glen McDonough calls a song-cue 'the guilty moment.' That's exactly the way I feel. In fact, I feel like a fool. The play stops without any excuse, and there I am with my song. When you stop to think of it, the situation is ridiculous.

"You should see some of the songs that I get," went on Miss Irwin. "The other day some one sent me a 'mother' song, saying he was sure it would just suit me. Can you see me singing a 'mother' song? Why, I'd be mobbed. The 'coon song' comes by every mail. The man who says that the 'coon song' is dead doesn't know what he is talking about. It's very much alive. I don't believe it will ever die. It is characteristic of the country."

Irwin's confidence in this ability was underscored in 1909 when composer Irving Berlin and composer/publisher Ted Snyder brought her some sample songs for interpolation into her upcoming play Mrs. Jim. After the pair went through their list, Berlin brought out an incidental number in manuscript form that he evidently had not thought too much of. However, May was immediately taken by My Wife Bridget, and asked Berlin to name a price on the spot for her to own it. He threw out a somewhat outlandish figure of $1,000, but May believed in the possibilities of this piece with her performing it, and startled Berlin by accepting the offer which gave her all future royalties. As usual, she was correct in her assessment and did fairly well by the tune.

While May's star started to fade in the 1910s, she still commanded attention at her performances. Her sister Flo was also seen from time to time, but rarely in the same place. On one 1914 ship passenger manifest Flo is shown as an actress who was naturalized in the United States and living in New York, with a home in Canada as well.  One play that May was in, Mrs. Black is Back, was turned into a full length feature film in 1914, her second film appearance following the famed kiss of 18 years prior. However she went in an out of retirement between 1915 and the early 1920s. For his 1918 draft record, Kurt was shown as a farmer living in Clayton, Jefferson County, Northern New York state, with May.

One play that May was in, Mrs. Black is Back, was turned into a full length feature film in 1914, her second film appearance following the famed kiss of 18 years prior. However she went in an out of retirement between 1915 and the early 1920s. For his 1918 draft record, Kurt was shown as a farmer living in Clayton, Jefferson County, Northern New York state, with May.

One play that May was in, Mrs. Black is Back, was turned into a full length feature film in 1914, her second film appearance following the famed kiss of 18 years prior. However she went in an out of retirement between 1915 and the early 1920s. For his 1918 draft record, Kurt was shown as a farmer living in Clayton, Jefferson County, Northern New York state, with May.

One play that May was in, Mrs. Black is Back, was turned into a full length feature film in 1914, her second film appearance following the famed kiss of 18 years prior. However she went in an out of retirement between 1915 and the early 1920s. For his 1918 draft record, Kurt was shown as a farmer living in Clayton, Jefferson County, Northern New York state, with May.In addition to the farm, she was known to have had summer home property nearby on Club Island near Grindstone Island in the Thousand Islands area of New York on the St. Lawrence Seaway, mentioned as early as 1897, and a winter hideaway on Merritt Island in Florida. She also owned an establishment in Clayton, New York, the Irwin Island Inn. There is a legend that May was responsible for the invention of Thousand Island dressing. In fact, she was merely part of a chain of people that helped to popularize it outside of upper New York state.

Active during the war as an entertainer in support of the effort, President Woodrow Wilson suggested to the press that he would like to appoint May Irwin as the official Secretary of Laughter for the United States. Following the war, as of the 1920 census, May was again working in Manhattan, but alone as Kurt was tending to their farm. She was listed as an actress in a theatrical company, and surprisingly as still unnaturalized, retaining her Canadian citizenship. In reality, May would be considered a United States Citizen by proxy of her marriage to her naturalized husband, a fact she may not have been aware of at that time.

In the early 1910s the Eisfeldts settled in Clayton, and by the early 1920s May had retired there, involved peripherally with her inn enterprise. She obviously still enjoyed making music, as her Clayton home had no less than seven pianos in it. The town of Clayton eventually named a street in her honor. In the late 1920s, having been retired from regular performance for some time, she was asked by her friend, agent Eddie Darling, if she could replace a sick premier opera singer, Emma Calvé, at The Palace, one of the more famous theaters in New York City. On just a few hours of notice May took the stage and worked for a whole week, explaining the situation to the audience. At the end of a very successful week for her and the producers, May refused to take any money, stating it was a favor for her friend and nothing more.

As of the 1930 enumeration, Kurt and May were shown in Clayton with no profession listed for either. Again, although he had been naturalized for decades, she had retained her Canadian citizenship status. May lost her older sister Flora in December, 1930. Flora succumbed to a heart attack that, according to the press, was brought on by a pending visit from her sister May. It was likely from other physical stresses as well, but May ended up using her visit to make final arrangements for her original stage partner.

Reaping the rewards of a long career and good investments, the Eisfeldts traveled the world during the early 1930s, often setting sail on The Resolute or The Reliance for their European adventures. Back in the United States May would sometimes make guest appearances in the "old-timers" shows at The Palace, and was known to have appeared on radio a couple of times as well. May finally succumbed at the age of 76 late in the decade, leaving a still substantial fortune to her husband and two sons, and a stellar legacy of the early days of Broadway to the rest of the world.

Most of the information was compiled by the author in public and private records and copious newspaper articles. Some additional information was found in a good substantial book set on vaudeville and early Broadway, Vaudeville, Old & New (2006) by Frank Cullen, Florence Hackman and Donald McNeilly.

Compositions

Compositions