There are times that a moderately talented composer emerges and gives us something relatively good and original. Then, even if they have the talent or the ambition, either they lack the drive or other realities of life get in the way, and they more or less disappear without realizing their full potential. Such is the case of Maurice Joseph Kerwin, for whom only limited information was discovered. First, let us clear up the spelling. On some music sheets he was shown to be Kirwin. However, census and other legal records for his family, with the exception of his death certificate, seem to settle on Kerwin as the correct or most common spelling. Therefore, except in context, Kerwin will be used here. Even the first name was altered at some point. He was born Morris J. Kerwin, Jr. in 1881 in Saint Louis, Missouri, to carpenter Morris Kerwin, Sr. and his bride Ellen Tiernan. There were six other siblings, including Rose (10/1875), Lilly (9/1878), George William (11/17/1884), Violet (1/20/1890), Robert (10/25/1892) and Arthur (12/1894). By the 1890s, Morris, Sr., appeared to have been working at times as a foreman, so was perhaps able to provide music lessons for his son that went a bit beyond what was taught in the public schools of St. Louis.

There were six other siblings, including Rose (10/1875), Lilly (9/1878), George William (11/17/1884), Violet (1/20/1890), Robert (10/25/1892) and Arthur (12/1894). By the 1890s, Morris, Sr., appeared to have been working at times as a foreman, so was perhaps able to provide music lessons for his son that went a bit beyond what was taught in the public schools of St. Louis.

There were six other siblings, including Rose (10/1875), Lilly (9/1878), George William (11/17/1884), Violet (1/20/1890), Robert (10/25/1892) and Arthur (12/1894). By the 1890s, Morris, Sr., appeared to have been working at times as a foreman, so was perhaps able to provide music lessons for his son that went a bit beyond what was taught in the public schools of St. Louis.

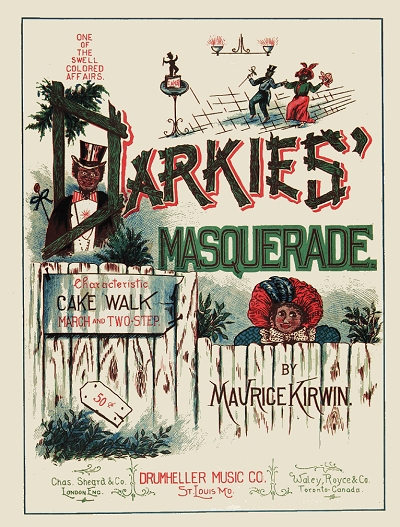

There were six other siblings, including Rose (10/1875), Lilly (9/1878), George William (11/17/1884), Violet (1/20/1890), Robert (10/25/1892) and Arthur (12/1894). By the 1890s, Morris, Sr., appeared to have been working at times as a foreman, so was perhaps able to provide music lessons for his son that went a bit beyond what was taught in the public schools of St. Louis.While little is known of his schooling, it is clear that Morris had some ambition to be a musician, perhaps professionally. His first known composition was potentially the jaunty 6/8 American Guard March, which in a couple of collections shows a possible 1897 copyright date, meaning he would have been 16 at that time. It was mentioned on other early music sheets with a 1900 copyright, and is confirmed to have been issued [again?] in 1910. Altering his name to Maurice Kirwin, he was able to get two more works published when he was just 18-years-old. Both the cakewalk Darkie's Masquerade and his Evening Star were issued in Saint Louis, the latter under his own banner. They were not outstanding by any means, but relatively polished (arranged by professionals, including D.S. De Lisle who had worked with Tom Turpin's Harlem Rag), and given the ragtime craze that was overtaking the country at that time, Darkie's Masquerade, under the Drumheller Music Company banner, sold relatively well. On the back of Light of Hope there was a sample of Dawn of Liberty by Robert Raffayolo, suggesting that Kirwin had issued more than just his own material in his short-lived career as a publisher. It must have all been somewhat encouraging to the young man. The 1900 census showed him as Morris, still living at home with his large family, and listed as a musician. Virtually all records after this time would show him as Maurice Kerwin.

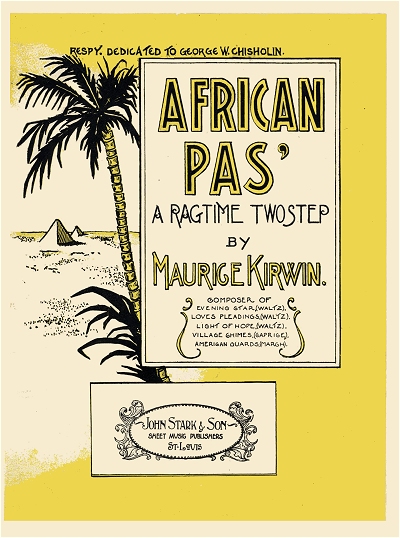

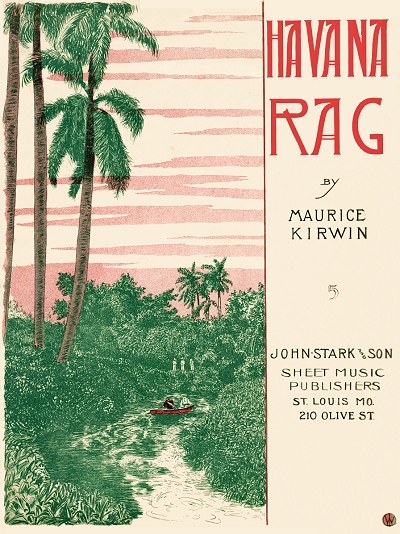

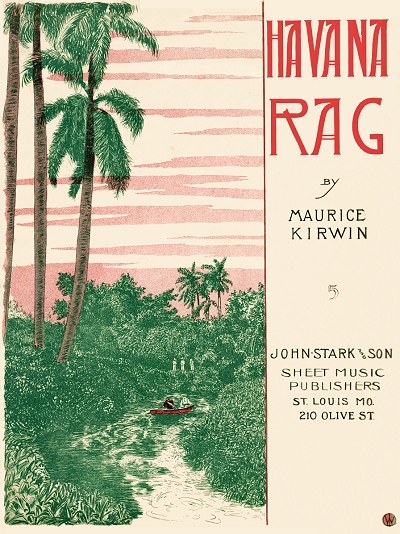

Maurice was hardly prolific, at least as a published composer, but he managed a select few pieces over the next several years. The year 1900 saw a waltz and a caprice, the latter using the popular "chimes" theme of treble chords often found in such pieces of this ilk. His next march/galop, In the Lead, made it all the way to an early QRS piano roll a few years after it was issued, as did a couple of his later compositions. Then came his most popular work, African Pas, his first real piano rag. It was issued in Saint Louis late in the year by esteemed ragtime publisher John S. Stark, so afforded Maurice some of the best possible promotion he would ever enjoy. As found on the back of some other Stark issues at the time, the piece was described as "easy and brilliant - good to catch the ragtime swing." In 1912 it was reissued as an orchestration in the iconic Stark folio Standard High-Class Rags, arranged by Etilmon J. Stark, and found in good company with such pieces as Maple Leaf Rag and Frog Legs Rag. African Pas' was followed in 1904 by his second Stark issue the Havana Rag. Not really evocative of Cuban themes of the time, it is not quite as dynamic as African Pas', but still had a relatively moderate run while promoted by the publisher. There were also a few newspaper mentions of Maurice playing his works at some social gatherings around Saint Louis, but evidently not working as a professional in a town that was quickly becoming dominated by black talent in the fields of ragtime, popular music, and even some interpretations of the classics.

His next march/galop, In the Lead, made it all the way to an early QRS piano roll a few years after it was issued, as did a couple of his later compositions. Then came his most popular work, African Pas, his first real piano rag. It was issued in Saint Louis late in the year by esteemed ragtime publisher John S. Stark, so afforded Maurice some of the best possible promotion he would ever enjoy. As found on the back of some other Stark issues at the time, the piece was described as "easy and brilliant - good to catch the ragtime swing." In 1912 it was reissued as an orchestration in the iconic Stark folio Standard High-Class Rags, arranged by Etilmon J. Stark, and found in good company with such pieces as Maple Leaf Rag and Frog Legs Rag. African Pas' was followed in 1904 by his second Stark issue the Havana Rag. Not really evocative of Cuban themes of the time, it is not quite as dynamic as African Pas', but still had a relatively moderate run while promoted by the publisher. There were also a few newspaper mentions of Maurice playing his works at some social gatherings around Saint Louis, but evidently not working as a professional in a town that was quickly becoming dominated by black talent in the fields of ragtime, popular music, and even some interpretations of the classics.

His next march/galop, In the Lead, made it all the way to an early QRS piano roll a few years after it was issued, as did a couple of his later compositions. Then came his most popular work, African Pas, his first real piano rag. It was issued in Saint Louis late in the year by esteemed ragtime publisher John S. Stark, so afforded Maurice some of the best possible promotion he would ever enjoy. As found on the back of some other Stark issues at the time, the piece was described as "easy and brilliant - good to catch the ragtime swing." In 1912 it was reissued as an orchestration in the iconic Stark folio Standard High-Class Rags, arranged by Etilmon J. Stark, and found in good company with such pieces as Maple Leaf Rag and Frog Legs Rag. African Pas' was followed in 1904 by his second Stark issue the Havana Rag. Not really evocative of Cuban themes of the time, it is not quite as dynamic as African Pas', but still had a relatively moderate run while promoted by the publisher. There were also a few newspaper mentions of Maurice playing his works at some social gatherings around Saint Louis, but evidently not working as a professional in a town that was quickly becoming dominated by black talent in the fields of ragtime, popular music, and even some interpretations of the classics.

His next march/galop, In the Lead, made it all the way to an early QRS piano roll a few years after it was issued, as did a couple of his later compositions. Then came his most popular work, African Pas, his first real piano rag. It was issued in Saint Louis late in the year by esteemed ragtime publisher John S. Stark, so afforded Maurice some of the best possible promotion he would ever enjoy. As found on the back of some other Stark issues at the time, the piece was described as "easy and brilliant - good to catch the ragtime swing." In 1912 it was reissued as an orchestration in the iconic Stark folio Standard High-Class Rags, arranged by Etilmon J. Stark, and found in good company with such pieces as Maple Leaf Rag and Frog Legs Rag. African Pas' was followed in 1904 by his second Stark issue the Havana Rag. Not really evocative of Cuban themes of the time, it is not quite as dynamic as African Pas', but still had a relatively moderate run while promoted by the publisher. There were also a few newspaper mentions of Maurice playing his works at some social gatherings around Saint Louis, but evidently not working as a professional in a town that was quickly becoming dominated by black talent in the fields of ragtime, popular music, and even some interpretations of the classics.While this was not the last of Maurice the composer, the reality of a limited income from occasional gigs and even less occasional payments for his scores may have set in. As early as 1903 he was shown working a day job as a bookkeeper. In late 1904 he suffered the loss of his oldest sister, Rose, followed by his mother just seven weeks later. Not long after that, he was seen working for the F.W. Humes food company as a city salesman, getting their goods distributed to grocers and hotels around Saint Louis. Before 1910 he was working with a flour mill as a salesman, and remained in that business for the rest of his career. In part, this may have been because he was married on June, 24 1904, to Elizabeth Cargher, also of Saint Louis. Their first child, Bernadine, was born in 1907. In the interim, that same year, Maurice managed to have his clever schottische, West End Belle, issued by the Bafunno Brother's Music Company. It was his last known publication. The 1910 census showed the Kerwins living just outside of downtown Saint Louis, with Maurice as a flour salesman.

In late 1904 he suffered the loss of his oldest sister, Rose, followed by his mother just seven weeks later. Not long after that, he was seen working for the F.W. Humes food company as a city salesman, getting their goods distributed to grocers and hotels around Saint Louis. Before 1910 he was working with a flour mill as a salesman, and remained in that business for the rest of his career. In part, this may have been because he was married on June, 24 1904, to Elizabeth Cargher, also of Saint Louis. Their first child, Bernadine, was born in 1907. In the interim, that same year, Maurice managed to have his clever schottische, West End Belle, issued by the Bafunno Brother's Music Company. It was his last known publication. The 1910 census showed the Kerwins living just outside of downtown Saint Louis, with Maurice as a flour salesman.

In late 1904 he suffered the loss of his oldest sister, Rose, followed by his mother just seven weeks later. Not long after that, he was seen working for the F.W. Humes food company as a city salesman, getting their goods distributed to grocers and hotels around Saint Louis. Before 1910 he was working with a flour mill as a salesman, and remained in that business for the rest of his career. In part, this may have been because he was married on June, 24 1904, to Elizabeth Cargher, also of Saint Louis. Their first child, Bernadine, was born in 1907. In the interim, that same year, Maurice managed to have his clever schottische, West End Belle, issued by the Bafunno Brother's Music Company. It was his last known publication. The 1910 census showed the Kerwins living just outside of downtown Saint Louis, with Maurice as a flour salesman.

In late 1904 he suffered the loss of his oldest sister, Rose, followed by his mother just seven weeks later. Not long after that, he was seen working for the F.W. Humes food company as a city salesman, getting their goods distributed to grocers and hotels around Saint Louis. Before 1910 he was working with a flour mill as a salesman, and remained in that business for the rest of his career. In part, this may have been because he was married on June, 24 1904, to Elizabeth Cargher, also of Saint Louis. Their first child, Bernadine, was born in 1907. In the interim, that same year, Maurice managed to have his clever schottische, West End Belle, issued by the Bafunno Brother's Music Company. It was his last known publication. The 1910 census showed the Kerwins living just outside of downtown Saint Louis, with Maurice as a flour salesman.Maurice and Elizabeth had on additional child in late 1912, their son, Vincent. In 1916 he was listed in the Saint Louis directory as the Vice President of the Independent Flour Company. However, most subsequent listing showed him as just a salesman, including his 1918 draft card which named Western Milling as his employer, and the 1920 federal census. The song Everything is Life in Dixie, with lyrics by Walter K. Boehm, was copyrighted in 1920, but verification of anything beyond what may have been a vanity issuance was not located, so it may not have even been printed. The 1930 enumeration showed him to be a city salesman for food products. By 1940, with his children gone from the home, there may have been marital issues, since Maurice was living with his younger brother George for that census, and Elizabeth in another location. She was not referenced either on his 1942 draft record, which showed Maurice as unemployed.

The Kerwins appear to have remained married but legally separated, which was confirmed in the 1950 census, showing Maurice living with his brother George, and without an occupation. They were also shown as married on the August 7, 1951, death certificate of Elizabeth, who died of complications from diabetes and gangrene of her foot and leg lasting as long as 6 months. Maurice succumbed just over a year later in September of 1952, showing as a widower, having been taken to the Little Sisters of the Poor for his last two months. He died of carcinoma of the colon, and was interred at Calvary Cemetery in north Saint Louis. More than a century after they were first issued, but too late for Mr. Kerwin to appreciate the recognition, some of his pieces are heard at ragtime festivals and on YouTube. Between that and "The Red Back Book," he will not be forgotten.

Thanks to Scott Joplin House researcher Bryan Cather for additional information concerning Kerwin's wedding.

Compositions

Compositions