Pauline Alpert, known to many of her fans as "The Whirlwind Pianist," was a product of the age of ragtime, but born too late to participate in it to any degree, and as a result took its offspring genres into new unique spaces that have hardly been matched since. She was not so prolific as a writer as she was with piano roll arrangements and brilliant recordings, but they are all worthy of examination as is her history. Note that in other collective articles that the timeline of events is often vague or conflicts with certain known facts and other biographies, so an earnest attempt has been made here to present the best possible representation of the chronology of Pauline's life.

Pauline was born in the Bronx borough of New York City to Russian immigrant Samuel A. Alpert and his New York native wife Anna Rosk (although Pauline had mentioned she might have been from Maryland). While both 1900 and 1912 have been cited as the possible year of her birth, New York City birth records, her Social Security and New York death records, her official obituary, and censuses subsequent to her birth easily confirm that year to be 1905. Samuel was listed as an artist in Manhattan directories and the 1910 enumeration, and according to Pauline in a June 1936 article in Popular Songs magazine, he specialized in portraits. At that, steady work was difficult to find, and the family lived in near-poverty for many years, moving to different locations in New York City and nearby. After having moved north to Rochester, New York, in the early 1910s, the couple gave Pauline a sister, Ethel Jacqueline (9/15/1915). At some point during this period, she was given an opportunity for a musical education as well around age seven, started by her mother, who Pauline noted was a talented singer and pianist, although she never listed it as an occupation.

Living a true hardscrabble existence on many levels, Pauline embraced music as many would as both a joy and a diversion. However, during The Great War of 1917-1918 it became a necessity as well. In order to supplement the family income Pauline, at age 11, took on younger piano students, asking twenty-five cents per lesson. She confided to performer and historian Peter Mintun later in life that the first popular tune she took to was All Alone by Irving Berlin. "Even at the age of eleven, I was putting in the little frills and things. I always had that knack." Her younger sister had acquired some talent as well, and was soon learning to play the violin.

To add to an already difficult existence, her father Samuel died in October 1919, potentially a victim of the ongoing flu pandemic, leaving Anna and her children to fend for themselves. Pauline persisted, and kept at the piano throughout her years at East High School in Rochester. Her playing prowess wone her a scholarship to attend the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester. Her goal was to be a concert pianist, and to that end she diligently studied classical music for four years in pursuit of that goal. It helped that some of the pressure was taken off of her mother, who was remarried on October 27, 1924, to Harry Hyman.

Her goal was to be a concert pianist, and to that end she diligently studied classical music for four years in pursuit of that goal. It helped that some of the pressure was taken off of her mother, who was remarried on October 27, 1924, to Harry Hyman.

Her goal was to be a concert pianist, and to that end she diligently studied classical music for four years in pursuit of that goal. It helped that some of the pressure was taken off of her mother, who was remarried on October 27, 1924, to Harry Hyman.

Her goal was to be a concert pianist, and to that end she diligently studied classical music for four years in pursuit of that goal. It helped that some of the pressure was taken off of her mother, who was remarried on October 27, 1924, to Harry Hyman.While her focus was on classical piano works and a concert career, Pauline did not totally ignore popular music trends. During many lunch hours at Eastman, and likely some evenings, she would entertain her fellow students at the piano, picking some popular songs along the way. But the budding talent was not satisfied with sticking to the score of many of these works, rearranging them with her knowledge of musical theory and classical technique, and turning out a unique hybrid that many would equate to the novelty piano style. Among her early favorites of the genre was the 1916 piece Nola by Felix Arndt, who, like her father, had been taken during the pandemic. She soon latched on to tunes by other contemporaries, particularly George Gershwin and Zez Confrey. Before she was even out of Eastman, Pauline had changed directions and wanted to pursue popular music performance instead. As the budding pianist recalled in the 1936 article (without a specific time line reference to her college experience but likely around 1925 to mid-1926):

A girl violinist and I entered a contest at the Rochester Temple theater. I was making my own arrangements, and making them in jazz. At the Temple, we met the dance team of Hackett and Delmar. They encouraged us. We went to New York as soon as possible. It was a very bad season. We only secured three or four days work out of as many months.

One of our engagements was in Glens Falls. The hotel we were stopping in burned down. My partner lost her violin. We both lost everything we had, even our clothes! …

The we had to go home. I got work as secretary in the Ryan Vanilla concern… I smelled so of vanilla, I could hardly go out! The first thing I did when I reached home was to bathe. But that didn't help. The smell got into my clothes; Gee, it was embarrassing.

It is possible that Pauline got some notice when she won first prize in the Eastman School Amateur Piano Context at some point in 1926. Before long, she was back in New York City, determined to make another go of it. Notices for her programs broadcast on station WMSG were found in late May of the year, but if she was residing there yet is unclear. Pauline wrote and copyrighted two pieces in 1927, Perils of Pauline in the novelty style and a waltz tune, Night of Romance. During a stage show around this time, both she and her piano were covered with phosphorescent paint, and then put on a platform rigged to float above the stage, circling over dancers below. Then during one performance a pully snapped, but Pauline managed to escape serious injury in the incident. To commemorate the event, she composed Perils of Pauline, which was also the name of 1914 film serial starring Pearl White.

Notices for her programs broadcast on station WMSG were found in late May of the year, but if she was residing there yet is unclear. Pauline wrote and copyrighted two pieces in 1927, Perils of Pauline in the novelty style and a waltz tune, Night of Romance. During a stage show around this time, both she and her piano were covered with phosphorescent paint, and then put on a platform rigged to float above the stage, circling over dancers below. Then during one performance a pully snapped, but Pauline managed to escape serious injury in the incident. To commemorate the event, she composed Perils of Pauline, which was also the name of 1914 film serial starring Pearl White.

Notices for her programs broadcast on station WMSG were found in late May of the year, but if she was residing there yet is unclear. Pauline wrote and copyrighted two pieces in 1927, Perils of Pauline in the novelty style and a waltz tune, Night of Romance. During a stage show around this time, both she and her piano were covered with phosphorescent paint, and then put on a platform rigged to float above the stage, circling over dancers below. Then during one performance a pully snapped, but Pauline managed to escape serious injury in the incident. To commemorate the event, she composed Perils of Pauline, which was also the name of 1914 film serial starring Pearl White.

Notices for her programs broadcast on station WMSG were found in late May of the year, but if she was residing there yet is unclear. Pauline wrote and copyrighted two pieces in 1927, Perils of Pauline in the novelty style and a waltz tune, Night of Romance. During a stage show around this time, both she and her piano were covered with phosphorescent paint, and then put on a platform rigged to float above the stage, circling over dancers below. Then during one performance a pully snapped, but Pauline managed to escape serious injury in the incident. To commemorate the event, she composed Perils of Pauline, which was also the name of 1914 film serial starring Pearl White.Having cut two trial sides for Victor Records in December of 1926, she came back to their studio in January, June and December of 1927 to lay down a total of eight more for the label, including her first two compositions, and other popular novelties such as Doll Dance and Dancing Tambourine. There were also two Vitaphone short sound films, What Price Piano (418) and Pauline Alpert (419), both copyrighted March 12, 1927, when she was 21 years-old. Neither film could be found online, but for What Price Piano, both the visual and audio elements are known to exist, albeit separately. However, since Warner Brothers was typically mining the vaudeville theaters of New York City to engage the acts for these shorts, it indicates that she was probably engaged by one during this period. In the few theaters equipped at that time to show Vitaphone Varieties, to most audiences she clearly lived up to their hype as a "SENSATIONAL PIANISTE IN A REPERTOIRE OF LATEST POPULAR NUMBERS!"

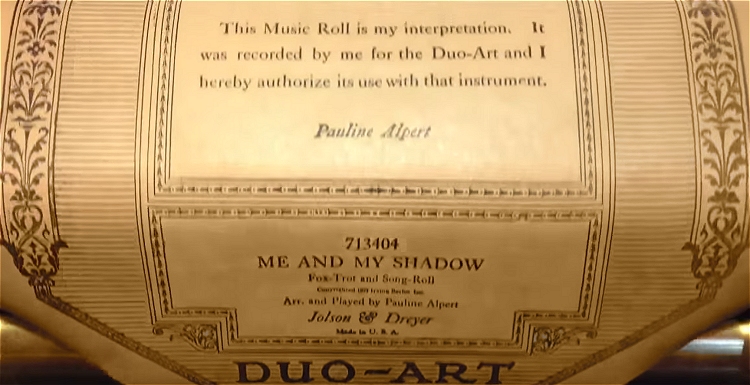

However, Pauline would make a more significant impact in the musical world with her piano roll work, particularly on the Duo-Art label, with which she established had a good relationship in late 1926, around the same time of her first Victor recordings. How she got the job, without being sought out by an talent scout or A&R person in a theater, in fact how she perhaps got all of them, was an act of sheer bravado on her part. According to Pauline, as relayed to Peter Mintun:

I had no contact with the Duo-Art people, though I had heard about them and found out where they were. I walked in and presented myself to the man [head arranger Frank Milne], sat down and played for him and he was flabbergasted!

First of all, I had a lot of nerve - you know, 'spunk', in those days, and I was about the only pianist they had who played too many fancy things. They said people (their roll buyers) would not believe I was doing all that. 'They will think we are editing more notes in!' I was always a little bit over arranged, so I used to try to simplify some of the rolls I made. It's wonderful to hear that my rolls are listened to after so many years.

Frank [Milne] was a very nice fellow. I knew him very well. He moved to East Rochester where their main plant was and that's where the recordings went on. I worked for him on 57th Street in New York, where they had their recordings done then.

Pauline's first rolls were listed in a January 1927 edition of the Music Trade Review, and started flowing out regularly for some years. It wasn't long before she was either found by or promoted to Broadway, perhaps by her Duo-Art representative. As noted in the March 26, 1927 issue of the Music Trade Review:

Two popular Duo-Art artists are featured in new Broadway shows. Pauline Alpert appears in "Lemaire's Affairs" and Rubie Bloom appears in "Lucky," at the New Amsterdam. These artists have produced recordings of Broadway's latest popular hits for the Duo-Art

Soon, Pauline would be playing at the Roxy Theater as well as the Paramount Theatre, which brought her to the attention of the Fachon & Marco theatrical booking company. Given that sound features were still in the near future, there were still national tours of talented artists like Pauline, and before 1927 was out she had been introduced to West Coast audiences as far of as San Francisco and San Jose, then Los Angeles and San Diego. With the piano rolls, the records, the radio shows and the continued live bookings, Pauline had made it to the big time within 18 months, partially through her amazing talents, and partly through he refusal to accept anything less than an honest chance to prove herself.

Soon, Pauline would be playing at the Roxy Theater as well as the Paramount Theatre, which brought her to the attention of the Fachon & Marco theatrical booking company. Given that sound features were still in the near future, there were still national tours of talented artists like Pauline, and before 1927 was out she had been introduced to West Coast audiences as far of as San Francisco and San Jose, then Los Angeles and San Diego. With the piano rolls, the records, the radio shows and the continued live bookings, Pauline had made it to the big time within 18 months, partially through her amazing talents, and partly through he refusal to accept anything less than an honest chance to prove herself.While the recordings stopped for a while after 1927, Pauline's piano roll interpretations continued to delight and amaze the buying public who were fortunate enough to own a Duo-Art reproducing piano, and they sold relatively well. Those who saw her in person, especially in her later years, were in awe of how a woman with a statue of less than 5'3" could command the keyboard as best as the most powerful male pianists. During her national tour with the Fachon & Marco, her name was well-touted in newspaper advertising and her reputation grew. What Price Piano was shown well into 1929 as more theaters installed Vitaphone equipment, further giving her a public presence. Among those Pauline toured with were singer Milton Douglas, and a man with a stage drunk comedy act whose name was Roy Rogers, but decidedly not the same as Leonard Slye who would take that same name in the 1930s and become a major cowboy star. This Roy was a bit older and had started out as an acrobat in Australian music halls before joining the Fachon & Marco organization. To that end, a curious article hit several newspapers in mid-April, 1929:

A VAUDEVILLE love affair which blossomed la the wings was revealed on Broadway yesterday with the announcement that Roy Rogers, musical comedy and vaudeville star, and Miss Pauline Alpert, song writer, will be married in Chicago, June 2 [1929].

Whether or not this was simply a publicity ploy or there was real intention behind this announcement remains unclear. However, the prediction never manifested itself, and Pauline remained single. (In the late 1930s, after having sued and settled with Frye for appropriating his unique name, Rogers returned to Australia on the Tivoli circuit.) After the first or second tour Pauline appeared in the 1930 census living on W. 48th street in an apartment building with several other tenants who had jobs connected with the theater, and showed theater pianist as her vocation. She also continued her work for Duo-Art and started to be heard more on the airwaves as the 1930s progressed. However, other than two sides cut for Victor in 1932, there was no other known audio recording activity during the 1930s.

(In the late 1930s, after having sued and settled with Frye for appropriating his unique name, Rogers returned to Australia on the Tivoli circuit.) After the first or second tour Pauline appeared in the 1930 census living on W. 48th street in an apartment building with several other tenants who had jobs connected with the theater, and showed theater pianist as her vocation. She also continued her work for Duo-Art and started to be heard more on the airwaves as the 1930s progressed. However, other than two sides cut for Victor in 1932, there was no other known audio recording activity during the 1930s.

(In the late 1930s, after having sued and settled with Frye for appropriating his unique name, Rogers returned to Australia on the Tivoli circuit.) After the first or second tour Pauline appeared in the 1930 census living on W. 48th street in an apartment building with several other tenants who had jobs connected with the theater, and showed theater pianist as her vocation. She also continued her work for Duo-Art and started to be heard more on the airwaves as the 1930s progressed. However, other than two sides cut for Victor in 1932, there was no other known audio recording activity during the 1930s.

(In the late 1930s, after having sued and settled with Frye for appropriating his unique name, Rogers returned to Australia on the Tivoli circuit.) After the first or second tour Pauline appeared in the 1930 census living on W. 48th street in an apartment building with several other tenants who had jobs connected with the theater, and showed theater pianist as her vocation. She also continued her work for Duo-Art and started to be heard more on the airwaves as the 1930s progressed. However, other than two sides cut for Victor in 1932, there was no other known audio recording activity during the 1930s.The Great Depression, which slowly overtook the United States and part of the globe following the October 1929 Stock Market crash, was especially hard on non-essential businesses, of which music was considered to be one of them despite the respite it brought from the woes of society of the 1930s. Pauline, who had lost her mother in 1931, was still touring during that year, but many previously lucrative gigs were drying up. Steady musician jobs were usually at the lowest or highest end of the spectrum, with the best of the steadier gigs in radio or theater on the East Coast and Midwest, and film production on the West Coast. While Pauline continued to play for Duo-Art into the 1930s, the roll business was hit as hard as the audio recording business, both trying to compete with radio, which essentially free except for the cost of the receiver and an occasional tube. Pauline's talent was, as such, considered top-notch enough that she was able to sustain a fairly good living throughout the decade playing frequently for stage shows and over the airwaves.

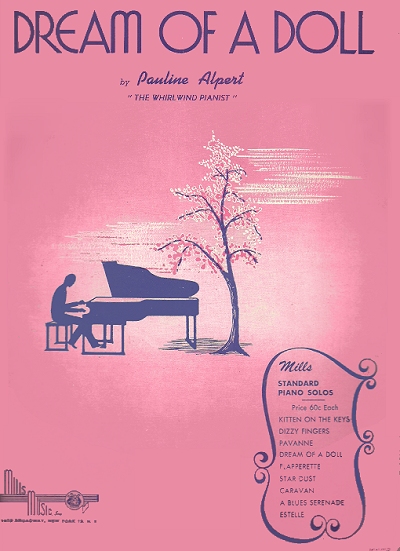

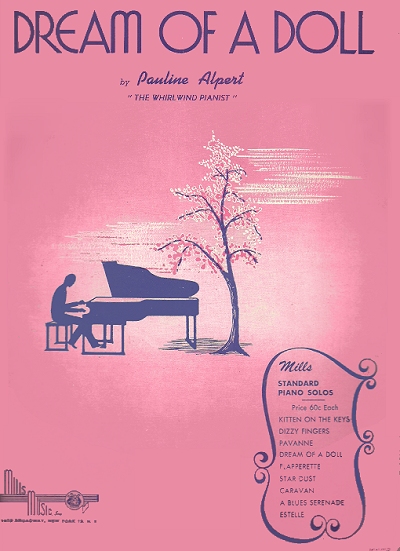

Pauline developed a good relationship with both the management and audiences of the early CBS flagship stations and among the oldest on the air, WOR 710, in New York City. It would become part of the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS) in 1934, and she continued with them through the changeover. Over time, she adopted her own composition from 1934, Dream of a Doll, as her opening theme music.

Most of the shows during this time were solo piano, but some had her accompanying singers or the occasional instrumentalist or small orchestra. The time of day varied, as she did morning shows as well as mid-to-late evening appearances. Most of the shows were between fifteen to twenty minutes in length. Pauline also appeared as a guest on some radio broadcasts, including one headed by singer Rudy Vallee, who in March 1933 called her "the greatest living woman pianist." Perhaps a stretch, but not too much of one. Unfortunately, there are few transcript recordings of her near-daily radio appearances during the height of the 1930s, but it is surmised that she must have been both prolific in her repertoire and popular with East Coast audiences. On an occasional night off, she could be heard playing at dinner clubs or special gatherings, often garnering mentions in the New York Sun and other papers around town.

|

Then there was Pauline's considerable circle of friends, which understandably would have been many of the working pianists and composers in New York City as well as entertainers and instrumentalists. Among them was George Gershwin, who regarded Pauline highly, as did his mother. Pauline's sister Ethel recalled that after George's death in 1937 Mrs. Gershwin happened upon Pauline playing on a cruise ship and asked that she visit the Gershwin home on her return to Manhattan. When she did, she was introduced to George's younger brother Arthur Gershwin who asked to take piano lessons from her, which she gladly did for some time. Another friend was Zez Confrey. In what was likely the late 1920s when Pauline was still playing for either the Roxy or Paramount theater, Confrey slipped in to hear her as she happened to play his own iconic novelty Kitten on the Keys during her performance. Pauline would later insist that both Kitten on the Keys and Dizzy Fingers were among her favorite go-to pieces. Another admirer was classical pianist Arthur Levine, who, according to Ethel, met her at a party and said, "My dear Pauline, I wish I could play the way you do!" She was occasionally profiled, as in the June 1936 issue of Popular Songs, from which more is quoted here:

A beauteous girl, is this whirlwind of a pianist. She has large blue-gray eyes, set wide apart. Her very long,

black eyelashes look mascaraed, but aren't. Fluffy titian hair sets as a Quaker bonnet over her smooth brow. She

is young, fresh and strong. But the atmosphere of her youth clings about her like a heavy, white fog. Perhaps,

her early fight for existence was easier than is her battle now to be happy and forget…

Pauline is a singularly engaging young person because she combines the manners of a sheltered home-girl with the thinking of a smart young business woman. She is a good listener, as well as conversationalist. She would like to sing, but declares she has no voice.

Every "fan" is a "friend" to Pauline. "I answer every fan letter, and I have kept every one that I have received;" she told me with unaffected pleasure.

Pauline is not married, but no girl on Broadway is a finer catch. What George Gershwin is among bachelor composers, Pauline Alpert is among the women. Music is never far from this musical girl's thoughts. It crowns all other subjects, as though all else might be fables and only music real.

She loves to dance and sing. She drives a car expertly. After only three weeks at the wheel, she drove to California. Blue is her favorite color.

"Oh, I think every girl should marry!" she nodded her lovely head. "I hope when I fall in love it will be with someone who loves music. Oh, I'd have to marry a man who loved music! It is my life. It is more than bread to me. It helps me to forget! It brings me happiness."

Pauline managed to get another Vitaphone short appearance in 1935 in the comedy musical Katz Pajamas starring actress Fifi D'Orsay. The pianist was cast as Pauline the Pianist, which was blatant typecasting of course, but all in good fun.

Beyond that, there are no other known film appearances. And, despite the house pianist of choice for the inestimably popular Paul Whiteman Orchestra being Roy Bargy, in addition to composer Dana Suesse and singing pianist Romana Davies, Pauline was featured on some of his radio shows as a soloist, finding herself in good company. Otherwise, she continued her steady work at WOR throughout the remainder of The Depression and into the 1940s. There were occasional appearances touted at everywhere from Pelham PTA Annual Show to the Women's League of Israel (she likely was from Jewish heritage but this was challenging to pin down), but outside of that she kept her personal life largely to herself and tended to not cause any notice in the newspapers beyond her stellar whirlwind performance style. By this juncture, and possibly going back to the mid-1930s, any Duo-Art rolls coming out with her name on them were most likely the imitations that had been laid out by Frank Milne, and not Pauline's actual sparkling performances. At the same time, she added the new medium of television to her resume, appearing on the NBC experimental station W2XBS in New York as early as April 24, 1940, and possibly a couple more occasions.

|

The 1940 census showed Pauline living in Manhattan, still hosting her younger sister, Ethel, who was listed as a secretary for Provident Loans, with Pauline still as a pianist on WOR. Her living situation would soon change, however. On August 9, 1940, her dream of finding a good man who loves music came to fruition when she married Dr. Sidney Barnet Rooff (5/8/1901) in Manhattan. The couple would live the rest of their collective lives in West Bronx, New York, mostly at an elegant apartment building at 1505 Grand Concourse. As for music, Dr. Rooff was a violinist who played in an orchestra manned by other doctors, which performed at hospital and charity events among other occasions. It is not a stretch to imagine that Pauline may have accompanied her husband now and then.

Lives all over the worlds at the end of The Great Depression when war escalated in Europe, and then into the Pacific, involving the United States as 1941 came to a close. For Pauline, however, the change was minimal. She continued to play for WOR, part of the Mutual Broadcasting System since 1934, but it is unclear if any of her performances were broadcast across the network, most likely confined to the New York City area. Pauline had regular slots on WOR throughout the war, mostly as a soloist, and remained popular and inexpensive programming for the station, which had also added an FM transmitter in 1941. She performed for several benefits and war bond loan events. One rather substantial show as a benefit for Ahavath Israel held in Kingston, New York, featuring popular Jewish comedian Henny Youngman as the Master of Ceremonies, the orchestra of Enoch Light (who would later found Waldorf Music Hall, Grand Award and Command records), Pauline, and a few other musical and dance acts. According to her official ASCAP biography, she performed at Army camps during the war, most likely in the United States. There were also three command appearances at the White House in Washington, DC, including two for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and one in 1946 for President Harry S. Truman.

According to her official ASCAP biography, she performed at Army camps during the war, most likely in the United States. There were also three command appearances at the White House in Washington, DC, including two for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and one in 1946 for President Harry S. Truman.

According to her official ASCAP biography, she performed at Army camps during the war, most likely in the United States. There were also three command appearances at the White House in Washington, DC, including two for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and one in 1946 for President Harry S. Truman.

According to her official ASCAP biography, she performed at Army camps during the war, most likely in the United States. There were also three command appearances at the White House in Washington, DC, including two for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and one in 1946 for President Harry S. Truman.By late 1945, after the war had ended, Pauline started appearing more often in local vaudeville and Broadway theaters, and even an occasional turn at Coney Island when she wasn't tearing it up on WOR. She was also involved with some events of the United Order of True Sisters, the female answer to the Jewish B'nai B'rith organization. While no timeline is clear or definitive instances found, Pauline also performed for a few ocean liner cruises going back to the mid-1930s and into the postwar years.

While her Duo-Art days were behind her, Pauline did manage to get back into recording studios near the end of and directly after the war. In 1944 she cut eight sides for the Chicago-Based Sonora label, which had recently opened a New York office, using the WOR studios for its recording sessions. They included a mix of audience favorites, some Raymond Scott numbers, and her signature Dream of a Doll. Sonora, which during the war and concurrently a musician's union recording strike, had largely been reissuing purchased masters from 1942 to 1944, and selling them at a good pace when new music on records was sometimes hard to come by. So, having Pauline in their catalog along with some other New York orchestras created a temporary sales bump, which would last into the late 1940s as they expanded their catalog. From 1943 to 1945 she also made a few 16-inch records for the Muzak company, which was providing customized music for everything from hotel lobbies and elevators to medical offices and small businesses. While only one definitive title was unearthed in research with her name on it, she evidently cut several more as Peggy Anderson, using the same initials as her own. Later in life she told Galen Wilkes that "she would occasionally go into a lobby and hear herself playing! 'It's nice to know I'm still around.'"

So, having Pauline in their catalog along with some other New York orchestras created a temporary sales bump, which would last into the late 1940s as they expanded their catalog. From 1943 to 1945 she also made a few 16-inch records for the Muzak company, which was providing customized music for everything from hotel lobbies and elevators to medical offices and small businesses. While only one definitive title was unearthed in research with her name on it, she evidently cut several more as Peggy Anderson, using the same initials as her own. Later in life she told Galen Wilkes that "she would occasionally go into a lobby and hear herself playing! 'It's nice to know I'm still around.'"

So, having Pauline in their catalog along with some other New York orchestras created a temporary sales bump, which would last into the late 1940s as they expanded their catalog. From 1943 to 1945 she also made a few 16-inch records for the Muzak company, which was providing customized music for everything from hotel lobbies and elevators to medical offices and small businesses. While only one definitive title was unearthed in research with her name on it, she evidently cut several more as Peggy Anderson, using the same initials as her own. Later in life she told Galen Wilkes that "she would occasionally go into a lobby and hear herself playing! 'It's nice to know I'm still around.'"

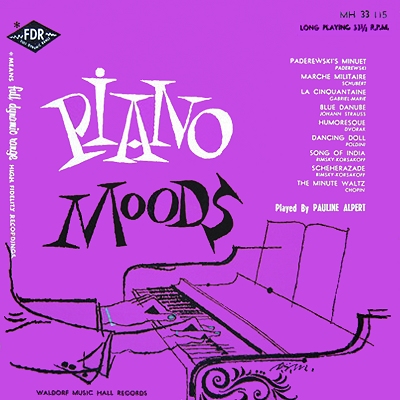

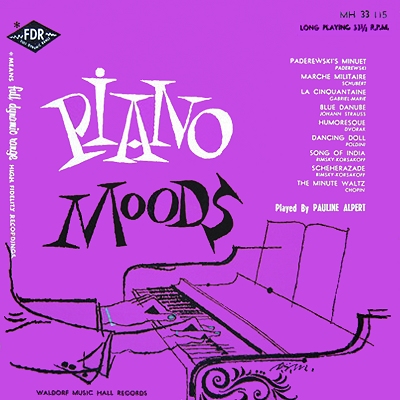

So, having Pauline in their catalog along with some other New York orchestras created a temporary sales bump, which would last into the late 1940s as they expanded their catalog. From 1943 to 1945 she also made a few 16-inch records for the Muzak company, which was providing customized music for everything from hotel lobbies and elevators to medical offices and small businesses. While only one definitive title was unearthed in research with her name on it, she evidently cut several more as Peggy Anderson, using the same initials as her own. Later in life she told Galen Wilkes that "she would occasionally go into a lobby and hear herself playing! 'It's nice to know I'm still around.'"Then, Pauline made a series of classical music recordings in 1944 for the small Long Island-based Pilotone label, one of the earliest to make the move to vinylite records, which had considerably lower noise than the traditional shellac 78-RPM discs. It is unclear how many sides were cut. Eight were released initially in 1946. After the advent of the Long Playing (LP) record in 1948, they were reissued by Enoch Light's Waldorf Music Hall label in 1955 along with one additional track. They were further reissued around the same time via the Canadian-based Sparton Records label, along with an additional eight tracks. This strongly suggests that Pauline had cut as many as sixteen tracks for Pilotone in 1946, which was likely her last studio recording session.

This strongly suggests that Pauline had cut as many as sixteen tracks for Pilotone in 1946, which was likely her last studio recording session.

This strongly suggests that Pauline had cut as many as sixteen tracks for Pilotone in 1946, which was likely her last studio recording session.

This strongly suggests that Pauline had cut as many as sixteen tracks for Pilotone in 1946, which was likely her last studio recording session.In the early post-war years there was change in the air. Many wanted to return to familiar things, but the country was advancing towards a much different culture, including moves to the new suburbs and the coming of broadcast television. To that end, Pauline's regular radio shows were ended by early 1947, and mentions of her appearances in the New York papers all but disappeared after 1951. Just ahead of that, the 1950 census, under which she used Alpert instead of Rooff, listed her as a pianist in theater and radio, albeit at the end of that rurn. Although only in her forties, it appears she settled in for the life of a doctor's wife. There was still the occasional guest appearance for one or another organization, and a late 1952 to early 1953 playing tour of parts of South America, but no records, no rolls, and no radio. While she had been on experimental television in its earlier years, any appearances beyond that are hard to verify. Her first heyday, which included two decades of celebrity and frequent performances, was over. Ironically, this was time, specifically 1953, that Pauline was finally admitted to ASCAP as a composer.

Ethel had gotten married to Robert Benezera (later changed to Benet) just a month after Pauline was wed to Dr. Rooff. However, she had a troubled marriage given her husband's temperament, drinking, and frequent unexplained absences. Ethel filed for divorce in 1960, and Pauline supported her in an scathing affidavit filed in May, detailing the transgressions she and Dr. Rooff had witnessed. It is likely that the Rooffs provided shelter for Ethel while she worked to move on with her life. Ethel was remarried in Florida to Mac Lorber in the fall of 1976. Beyond that, little was heard from the family until Sidney died in March 8, 1968, at age 66. Pauline, now 62, still maintained her energetic demeanor and kept up her piano skills, but she had all but faded into memory and possible obscurity. Until…

Beyond that, little was heard from the family until Sidney died in March 8, 1968, at age 66. Pauline, now 62, still maintained her energetic demeanor and kept up her piano skills, but she had all but faded into memory and possible obscurity. Until…

Beyond that, little was heard from the family until Sidney died in March 8, 1968, at age 66. Pauline, now 62, still maintained her energetic demeanor and kept up her piano skills, but she had all but faded into memory and possible obscurity. Until…

Beyond that, little was heard from the family until Sidney died in March 8, 1968, at age 66. Pauline, now 62, still maintained her energetic demeanor and kept up her piano skills, but she had all but faded into memory and possible obscurity. Until…As is common with many who want to remember and preserve the past, lovers of piano rolls and their instruments formed an organization to help preserve that history and collect a knowledge base associated with them. The Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors' Association (AMICA) was formed in 1963. While there was no shortage of interest in that time (the author's grandfather who owned a 1926 Weber Duo-Art, now in our possession, was an early member), interest grew during the rediscovery of ragtime music in the 1970s, which included a growing focus on those who cut the rolls. Somebody sought Pauline out in the mid-1970s, and she quickly became a celebrity amongst the AMICAns, as they sometimes called themselves. Visits from pianist/historians Peter Mintun and Galen Wilkes resulted in a more expansive telling of her history and interest in her process and time with Duo-Art. While they were generally not invited into her Bronx apartment, she was taken for meetings where a Duo-Art was present, and was able to hear her playing many years after she had first recorded the rolls. Having not owned a Duo-Art, this was a telling experience for her, bringing back a flood of good memories accompanied by stories. Some stories came from her admirers, including this one relayed by AMICA member Robert M. Taylor after her death, outlining the positive impact they had made upon her later life:

We met first at the Dayton Convention in 1978. 1 had heard in detail about Pauline Alpert from Molly Yeckley who was to go to the airport and pick her up. ..if she actually would come AMICAns were gathered in a reception area of some sort and all of a sudden Pauline Alpert was with us.

I have forgotten who it was that had some of her rolls… One was put on the Duo-Art: it began playing and she shook her head and said "faster"; the tempo was increased, she said "faster" again and was not content until the roll was going about tempo 110.

Of course, as we saw Pauline's physical disabilities, we thought that this was just a poor old woman with delusions of what she could do — then she sat down at the piano and we all became believers…

|

Pauline was always right there by her telephone. She answered in a voice that seemed to carry all the way to Philadelphia without the aid of a telephone. The television was always blaring in the background. She was always good for a nice long chat, but we all learned fairly quickly that getting Pauline to answer a letter was impossible.…

The Yeckleys and I somehow managed to get Pauline up to the Rainbow Room on the 65th floor of the NBC Building at Rockefeller Center. It was still just as she remembered it when she played there in the 1940's, and she was thrilled to be there she told us. Of course, it brought back a flood of memories and she told us that "I used to be so pretty and look at me now." She told us that she came upon some old photos and tore them all up because they made her so sad…

On another occasion… [we] had a lovely brunch on a Sunday at Windows on the World on the 110th Floor of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan. As we drove north up Sixth Avenue, Bobby pulled out the cassette tape recorder that we had purchased for Pauline; Bobby had recorded a number of Pauline's 78 records and he began to play the recorder softly, then a little louder. All of a sudden, Pauline shouted, "that's me," and Bobby handed her the tape recorder and told her that this was a present to her from us. That was one of the few times that I ever saw Pauline overwhelmed.

Pauline was clearly happy with the recognition and attention she received during her last decade and more of life. However, her disabilities eventually got the best or her, and she had to give up her Bronx apartment in the mid-1980s for assisted living across the Hudson in Thiells, Rockland County, New York, near her nephew, Alan Benet. Pauline Alpert died at St. Barnabus Hospital in the Bronx in the spring of 1988 at age 82, but was well-remembered by AMICAns in their regular newsletters, and at gatherings well into the 21st century. Pianist and piano roll interpreter Artis Wodehouse brought her back to life in the digital world in 1995 as part of her Keyboard Wizards of the Gershwin Era CD series. The first volume consisted of 27 recordings that she had made in the 1940s and before. Artis has also interpreted some of Pauline's rolls which can be found on YouTube. The Whirlwind Pianist was a singular and unique entity in the musical world, and we should all be glad that she left behind such a richly embellished melodic legacy.

Much of the material here was derived from the usual demographic sources, newspaper notices, and the 1936 article in Popular Songs magazine. However, additional input was gleaned from a collective articles document at the AMICA website, with significant contributions from my colleagues Galen Wilkes and Peter Mintun, both of whom had several visits with Pauline in the 1980s. Further thanks to pianist and roll interpreter Artis Wodehouse for keeping Mauline's music relevant and in circulation, and John Cowles who conveyed some information concerning stage actor (not cowboy star) Roy Rogers.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions