Paul Lingle was one of the benchmark performers of ragtime on the Barbary Coast (Northern California) during the first revival of traditional jazz and ragtime in the 1940s and 1950s, yet he left surprisingly little behind in terms of legacy, all of it of the best possible quality and pianistic passion. He was born in Denver, Colorado, at the beginning of the ragtime era, to Ohio native and cigar maker Curtis Roy Lingle, and his wife, Michigan native Cora Mae Harrison Merrow. Paul was the youngest of four surviving children out of five born to Cora, including William Harrison Merrow (12/16/1886), Roy David Merrow (9/1/1887), and Della Mae Merrow (3/24/1890), all with Cora's former husband William Merrow, one other having died in infancy. At the time of Paul's birth the Lingle family lived at 5046 W. 36th Avenue in Denver.

Taking to the piano at around five or six years of age, Paul actually had the benefit of listening and learning from great pianists of the ragtime era who passed through Denver when his dad, a fine cornetist, played with them. Much of his training was classical, of course, and he kept some of those pieces, such as the works of Chopin and Liszt, under his fingers throughout his life.

As of the 1910 census Curtis had gone into music full time, listing himself as an orchestra musician. Four years later, Paul started traveling with his father at age 12, largely on the Chautauqua Vaudeville circuit, a program designed to bring all types of culture to small town America, from 1915 to 1917. Paul later noted that this was the time in which he took a great interest in the rags of the famous composers of that era, including Scott Joplin and W.C. Handy.

|

However, the composer/performer that influenced Paul the most was "Jelly Roll" Morton, who was making a name for himself on the west coast during that period. Lingle also attended the 1915 World's Fair in San Francisco with his father, where the New York dynamo Mike Bernard and local Oakland whiz kid Jay Roberts performed. Near the end of the fair he encountered Morton's live performances for the first time and was hooked. Something Paul also learned while on the road was that musicians without a familiar name only get paid for playing what's in style, so he made sure to always adapt. He continued on his own after World War One, and in spite of his love for ragtime, quickly learned that jazz was taking over, so simply shifted his style a bit.

By 1919 Lingle had moved to California where he would spend the next three decades. He started working in some of the mining areas of Central and Southern California. In 1920, Paul is shown in San Bernardino in Southern California as a pianist/musician, at the slightly inflated age of 19, and on his own. That same year found him at the Del Mar club up in San Francisco. During that stint he availed himself of the opportunity as often as he could to hear Joseph "King" Oliver and his New Orleans jazz band playing at the Pagoda Ballroom on Market Street. After drifting around several venues in California, Paul settled in Los Angeles for a while, playing with the Oaks Tavern Players, a small orchestra managed by Oaks Tavern owner Frank Relter. Paul finally worked started his own group in 1925 at Mike Lyman's Tent Café in Los Angeles that featured Larry Shields of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band on clarinet. The following year found him at Balboa Island with the orchestra of Jimmy Grier, a clarinetist who had recently left Gus Arnheim's orchestra, in a group that included trombonist Glenn Miller. In 1928 Paul was back in San Francisco fronting his own small band at Fior D'Italia, but he also worked on some ocean cruise lines from time to time over the next decade as indicated by ship's manifests, preferring cruises to the Orient and back.

Paul's propensity for ragtime rhythms and his work in both Southern and Northern California got Lingle an invitation to come to Warner Brothers Studios to perform behind none other than Al Jolson in a couple of his early films, including The Singing Fool (sometimes referred to as Sonny Boy) in 1928 and Mammy in 1930. There are rumors that he had also played for the single live dialog scene in The Jazz Singer but that was actually either his colleague Bert Fisk or Jolson's musical director Louis Silvers. Lingle seems to have favored the Barbary Coast over Los Angeles, and commented later that he felt that Hollywood was becoming too commercial and wasn't fun anymore." By mid-1930 he was a Bay Area resident. Paul was living in San Francisco with his singer wife of around three years, Bertha "Betty" Lingle (of Russian parentage), listed as a musician who was employed "anywhere." This was essentially true as Lingle was seen virtually everywhere in the Bay Area for the next 22 years.

During the 1930s Lingle became a regular with trumpeter Al Zohn's jazz band, and was soon frequently employed by many radio stations either for background or foreground piano, primarily as a staff pianist at KPO. Most of what he played was contemporary to the time, but he would break out in a rag or two with his heavy left-hand keeping a steady thumping rhythm, one of the few players who continued to do so during the largely ragtime-deficit decade. In order to supplement the playing work during the lean years of the Great Depression, Paul also took up piano tuning as a trade, some weeks preferring that to the rigors of late night performance. Just the same, associates say that he could drink with the best of them and still play flawlessly. There were occasional stories in the newspapers about arrests for drunk driving as well. One Lingle story concerns when he was rooming with another musician in an apartment with Murphy-bed variations that stored under a nook in the wall.  He evidently came home plastered, so a couple of the guys there pushed his bed into its nook and locked it up for the night. When he woke with a hangover to find solid wood only a couple of inches from his face, he evidently shouted out "Oh my God! They've buried me alive!"

He evidently came home plastered, so a couple of the guys there pushed his bed into its nook and locked it up for the night. When he woke with a hangover to find solid wood only a couple of inches from his face, he evidently shouted out "Oh my God! They've buried me alive!"

He evidently came home plastered, so a couple of the guys there pushed his bed into its nook and locked it up for the night. When he woke with a hangover to find solid wood only a couple of inches from his face, he evidently shouted out "Oh my God! They've buried me alive!"

He evidently came home plastered, so a couple of the guys there pushed his bed into its nook and locked it up for the night. When he woke with a hangover to find solid wood only a couple of inches from his face, he evidently shouted out "Oh my God! They've buried me alive!"Another fine Lingle story that could be about any number of pianists, including his associate Burt Bales, was about an odd noise. When he was doing one of his regular shows at KPO a disturbing noise kept coming over the speakers in addition to the piano. The engineers apparently took apart and reassembled much of the electronic pathway to find the offending noise, in the end someone discovered it by standing in the studio as Lingle performed. It was Paul who was humming - somewhat out of tune - as he played. This comes across clearly in some of the rare recordings left behind. Paul was also known to be moody with effervescent highs and depressive lows, often taking visible offense if the listening audience simply didn't seem to appreciate what he was playing. Lingle was, perhaps (unsubstantiated but representative), a victim of mild bi-polar disorder.

In the 1940 census, taken in San Francisco, Paul was listed as a musician in a dance orchestra, and Betty (as Bertha) working as a cashier in a theater. By the early 1940s Lingle was actually tuning much more than playing, having moved down south from the Bay Area to a custom-built home in Santa Cruz. He felt that tuning was a much more profitable and respectable profession. This was the time when trumpeter Lu Watters, who had worked with Lingle several times in the 1930s, and fellow ragtime pianist Wally Rose were building up a head of steam for what would become the great traditional jazz revival of the 1940s. They formed the Yerba Buena Jazz Band in 1939 or 1940, and Paul had been part of the original core of that group until Watters chose Rose to replace him. The group started making recordings in late 1941 and early 1942.

World War II interrupted any normalcy that was to be had, and they would not fully reassemble until 1946. During the war when Rose was off in the United States Navy, as much of the group as possible was performing locally using Burt Bales and Forrest Brown as fill-in pianists. Lingle and Watters, both very strong-headed and uncompromising, were often at odds, and ended up not speaking for several years. Bob Helm postulated that it was because Paul, being primarily a solo pianist, might have tried to control the tempo and dynamics of a tune from his position at the keyboard. Otherwise there would have potentially been recordings of Lingle with the group. Moving back to the Bay Area from Santa Cruz in late 1943, he worked for a while at a 24 hour bar in Richmond, California, near the Kaiser ship yards. In 1943 and 1944 jazz historian Rudi Blesh held a series of concerts and seminars at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Lingle played in ensembles for several of those concerts. According to trombonist Bill Bardin, Paul had a method of accenting chords that involved a brief rise from the bench so he could throw most of his body weight behind the crashing chord. It was not used often, but made its point when exercised.

War time gigs were not always plentiful, but musicians were necessary for both civilian and military morale, especially in Oakland and San Francisco were both the Navy and Marines had bases. One of the places where Paul fronted small ensembles to orchestras was the Broadway Dancing Academy in Oakland. One of the dances frequently practiced there was the so-called grind, often used when tired couples just held on to each other and moved slowly in a grinding motion. The job was literally a grind, and often referred to either as a "dime jig" or a "grind." The work was tedious and grueling, where the band played 90 to 120 second tunes for the dime-a-dance crowd, sometimes playing as many as 200 a night. His core ensemble consisted of himself, Bill Bardin on trombone, Al Zohn on trumpet, and Ellis Horne on clarinet. Paul had to pick the repertoire, set the tempo, and play almost the entire time, certainly more than anybody else. However, Bardin was of the opinion that Paul held the position because he could play however he wanted with dictation from the management. He was always there with his trusty tuning hammer and a case full of lead sheets. After a long time on the gig, Paul had a falling out with Ellis and the ensemble started to crumble from that time. He eventually left the grueling dance work for a new gig Oakland's Jug Club.

The work was tedious and grueling, where the band played 90 to 120 second tunes for the dime-a-dance crowd, sometimes playing as many as 200 a night. His core ensemble consisted of himself, Bill Bardin on trombone, Al Zohn on trumpet, and Ellis Horne on clarinet. Paul had to pick the repertoire, set the tempo, and play almost the entire time, certainly more than anybody else. However, Bardin was of the opinion that Paul held the position because he could play however he wanted with dictation from the management. He was always there with his trusty tuning hammer and a case full of lead sheets. After a long time on the gig, Paul had a falling out with Ellis and the ensemble started to crumble from that time. He eventually left the grueling dance work for a new gig Oakland's Jug Club.

The work was tedious and grueling, where the band played 90 to 120 second tunes for the dime-a-dance crowd, sometimes playing as many as 200 a night. His core ensemble consisted of himself, Bill Bardin on trombone, Al Zohn on trumpet, and Ellis Horne on clarinet. Paul had to pick the repertoire, set the tempo, and play almost the entire time, certainly more than anybody else. However, Bardin was of the opinion that Paul held the position because he could play however he wanted with dictation from the management. He was always there with his trusty tuning hammer and a case full of lead sheets. After a long time on the gig, Paul had a falling out with Ellis and the ensemble started to crumble from that time. He eventually left the grueling dance work for a new gig Oakland's Jug Club.

The work was tedious and grueling, where the band played 90 to 120 second tunes for the dime-a-dance crowd, sometimes playing as many as 200 a night. His core ensemble consisted of himself, Bill Bardin on trombone, Al Zohn on trumpet, and Ellis Horne on clarinet. Paul had to pick the repertoire, set the tempo, and play almost the entire time, certainly more than anybody else. However, Bardin was of the opinion that Paul held the position because he could play however he wanted with dictation from the management. He was always there with his trusty tuning hammer and a case full of lead sheets. After a long time on the gig, Paul had a falling out with Ellis and the ensemble started to crumble from that time. He eventually left the grueling dance work for a new gig Oakland's Jug Club.That Lingle truly loved the material of the ragtime era and just beyond was quite clear. On V-J Day in 1945, Lingle told his wife Betty, "I'm glad the war is over." She was a little surprised he even knew of the event since Paul was often in his own world. "Why, Paul?" she asked. "Because now I can play 'Japanese Sandman' again."

As the post-war traditional jazz revival grew, so did Lingle's reputation for his highly original ragtime and Jelly Roll Morton interpretations. He again became a fixture in San Francisco and a hot ticket in the clubs, usually as a solo performer. Evidently he was in demand based on his reputation, as blues guitarist Leadbelly (Huddie Ledbetter) had asked him to be his accompanist while performing in town, and veteran New Orleans cornetist Bunk Johnson befriended Lingle, teaching him many of the old New Orleans tunes he had been playing for so many years. Unfortunately, according to a 1945 article in the Santa Cruz paper, the local arm of the Amerian Federation of Musicians, still reinforcing racist rules championed by their "dictator in chief" James Caesar Petrillo concerning mixing white and black performers, prevented Leadbelly and Johnson from making records with Lingle and two other white associates, Ellis Horne and Squire Girsback. This was despite the fact that the public would not be able to tell what race each musician was in a purely audio medium, and disregarded the changing American landscape on race in music as well. Both musicians had to return back East, denying the world of a likely legendary recording session.

Paul's dynamic range was also extraordinary, as he could play at a whisper one moment then break strings or hammers the next (it's a good thing he was a piano technician!). His repertoire, while full of ragtime and Jelly Roll Morton selections, was also very deep, and he could usually fulfill requests while attaching his own unique brand to each performance. Although Lingle had often been hard to find by his fans, given the scattered pattern of his appearances, he found steady gigs for fairly long periods at the Jug Club in Oakland and, in 1949, the Paper Doll club on Union Street in San Francisco, a place that he said catered to "all three sexes." The combination of his drinking habits and time away from home to play an hour or two away late into the night likely put some strain on his marriage. So it is not a surprise that at some point in the early 1950s Paul and Betty were divorced.

The one thing his fans were not able to find were recordings of the legendary Lingle at their local record store. While he felt all right live and in a radio studio, Paul shied away from the traditional recording studios for a long time. He told people that he just did not feel he was ready to record anything for posterity.  However, in addition to a few surviving radio show transcriptions, some friends and fans managed to make some wire recordings and early magnetic tape recordings of Lingle in action from 1947 to 1951. While hardly under the best of conditions, and with dropouts and background noise limiting the fidelity, they still captured his range well. The best of these were made by an associate, Charles Campbell, in 1951 at the Jug Club. In order to get past Lingle's paranoia of recording equipment, Campbell let Lingle know simply that he would be recording, but did not say when. On the night he got the bulk of his tapes, Campbell and recordist Stan Page made sure the equipment was fairly well hidden so as to not throw Paul off. The fare from that session was mostly ragtime, which had recently come back into national vogue through the widespread popularity of Lou Busch at Capitol Records, and includes pieces not likely recorded in years, such as Good Gravy Rag and Pastime Rag #3. Also included were two of his own compositions, Black and Blue Rag and Dance of the Witch Hazels, the latter which incorporates elements of another Barbary Coast pianist's work, Jay Robert's Entertainer's Rag. Through the diligence of Paul Affeldt and his Euphonic label, most of these tracks were released from the 1970s to the 1990s on three albums, and many are still available on CD, even if out of print.

However, in addition to a few surviving radio show transcriptions, some friends and fans managed to make some wire recordings and early magnetic tape recordings of Lingle in action from 1947 to 1951. While hardly under the best of conditions, and with dropouts and background noise limiting the fidelity, they still captured his range well. The best of these were made by an associate, Charles Campbell, in 1951 at the Jug Club. In order to get past Lingle's paranoia of recording equipment, Campbell let Lingle know simply that he would be recording, but did not say when. On the night he got the bulk of his tapes, Campbell and recordist Stan Page made sure the equipment was fairly well hidden so as to not throw Paul off. The fare from that session was mostly ragtime, which had recently come back into national vogue through the widespread popularity of Lou Busch at Capitol Records, and includes pieces not likely recorded in years, such as Good Gravy Rag and Pastime Rag #3. Also included were two of his own compositions, Black and Blue Rag and Dance of the Witch Hazels, the latter which incorporates elements of another Barbary Coast pianist's work, Jay Robert's Entertainer's Rag. Through the diligence of Paul Affeldt and his Euphonic label, most of these tracks were released from the 1970s to the 1990s on three albums, and many are still available on CD, even if out of print.

However, in addition to a few surviving radio show transcriptions, some friends and fans managed to make some wire recordings and early magnetic tape recordings of Lingle in action from 1947 to 1951. While hardly under the best of conditions, and with dropouts and background noise limiting the fidelity, they still captured his range well. The best of these were made by an associate, Charles Campbell, in 1951 at the Jug Club. In order to get past Lingle's paranoia of recording equipment, Campbell let Lingle know simply that he would be recording, but did not say when. On the night he got the bulk of his tapes, Campbell and recordist Stan Page made sure the equipment was fairly well hidden so as to not throw Paul off. The fare from that session was mostly ragtime, which had recently come back into national vogue through the widespread popularity of Lou Busch at Capitol Records, and includes pieces not likely recorded in years, such as Good Gravy Rag and Pastime Rag #3. Also included were two of his own compositions, Black and Blue Rag and Dance of the Witch Hazels, the latter which incorporates elements of another Barbary Coast pianist's work, Jay Robert's Entertainer's Rag. Through the diligence of Paul Affeldt and his Euphonic label, most of these tracks were released from the 1970s to the 1990s on three albums, and many are still available on CD, even if out of print.

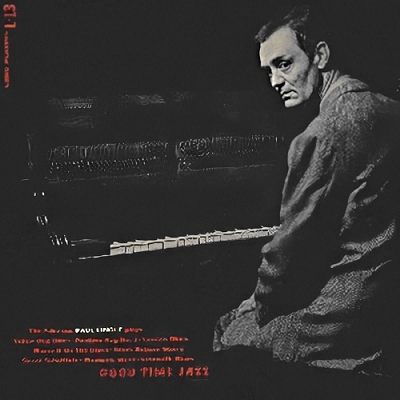

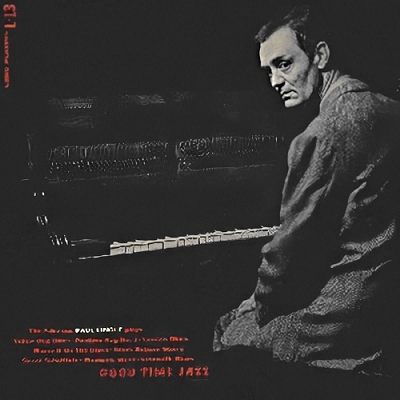

However, in addition to a few surviving radio show transcriptions, some friends and fans managed to make some wire recordings and early magnetic tape recordings of Lingle in action from 1947 to 1951. While hardly under the best of conditions, and with dropouts and background noise limiting the fidelity, they still captured his range well. The best of these were made by an associate, Charles Campbell, in 1951 at the Jug Club. In order to get past Lingle's paranoia of recording equipment, Campbell let Lingle know simply that he would be recording, but did not say when. On the night he got the bulk of his tapes, Campbell and recordist Stan Page made sure the equipment was fairly well hidden so as to not throw Paul off. The fare from that session was mostly ragtime, which had recently come back into national vogue through the widespread popularity of Lou Busch at Capitol Records, and includes pieces not likely recorded in years, such as Good Gravy Rag and Pastime Rag #3. Also included were two of his own compositions, Black and Blue Rag and Dance of the Witch Hazels, the latter which incorporates elements of another Barbary Coast pianist's work, Jay Robert's Entertainer's Rag. Through the diligence of Paul Affeldt and his Euphonic label, most of these tracks were released from the 1970s to the 1990s on three albums, and many are still available on CD, even if out of print.The person who first brought the Yerba Buena Jazz Band to the public through recordings on Watter's West Coast Jazz label, Lester Koenig, now had his own record company in 1951, Good Time Jazz. Koenig had hoped for over a decade to get Lingle into a studio just so something more "professional" could be released of his work. He was offered the Jug Club tapes but preferred to have the studio recordings. After some persistence on Lester's part, Lingle finally relented and came down to Hollywood in February of 1952. He recorded at least eleven cuts during three sessions at Radio Recorders, essentially the primary studio of Capitol Records, from February 11-13. Eight of these tracks were released on Good Time Jazz GTJ-13 in 1953 and two on a single. The remaining cut, Maple Leaf Rag, would surface many years later. By 1953, however, Lingle, who had long held the theory that as one gets older they simply should go to a warmer climate, had picked up his belongings and escaped the mainland to Hawaii where he would spend his remaining years.

Although Paul's original intent was to resume life as a piano tuner, he soon remarried, opened a small piano instruction studio, and eventually worked with bands entertaining tourists in Honolulu throughout the rest of the 1950s. Years of alcohol consumption, reportedly heavy at times, finally caught up with the dynamic pianist. Paul Lingle died just short of his 60th birthday in 1962. Thanks to Koenig, and following his initial efforts, others who have released the various nightclub recordings, transcriptions and private acetates, his legacy remains with us. Virtually any ragtime pianist who got their start in the 1950s and 1960s, including the author, will cite Paul Lingle as one of their primary influences; if not for style, at least for content and passion - all that from a few stories and ten storied cuts on vinyl.

If you want to hear Paul Lingle's dynamic playing, please consider the following two fine CD Recordings:

Some of the information contained within this biography came from liner notes by Robert Helm, Charles Campbell, Paul Affeldt and Lester Koenig, and a couple of stories related by historian Richard Zimmerman. Thanks also to Tom Hambleton who not only sent in a couple of articles, but as of 2017 owns Lingle's Santa Cruz residence, just four blocks from the Pacific Ocean. The remaining information was researched by the author from accounts found in periodicals of the time and other public records.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions  They Tore My Playhouse Down

They Tore My Playhouse Down