Born a bit late for ragtime, but just in time for hot piano jazz, Fillmore W. Ohman was born in New Britain, Connecticut, to Swedish immigrant minister Svengal G. "Sven" Ohman and his Illinois-born wife of Swedish parents, Hulda C. Lethin. He was the second of four boys, including his older brother Rudolph B. (11/1892) and younger brothers George W. (1905) and Ernest (1917). Many sources cite Philmore as his birth name, but it appears as Fillmore on the 1900, 1910, 1920 and 1930 census records as well as his 1917 draft record, a form that is usually very precise with such details. Sven Ohman was the pastor of St. Mary's Evangelical Swedish Lutheran Church in New Britain, and was found there in directories through the late 1910s as well as in the 1920 enumeration. There was a good-sized Swedish population in this central Connecticut town where the auburn-haired blue-eyed youth grew up.

Fillmore studied music in secondary school, and his aptitude was such that his teachers recommended sending their son off to Europe for further study, a fairly common practice at that time. However, on a pastor's salary this was not quite so easy. The compromise was to have him study music locally with Edward Laubin for four years, then an additional two years with local pipe organ master Alexander Russell, although with more focus on harmony and theory than organ work. At some point during this period, when he was a bit shy of 16, Phil, as he now preferred to be called, made his first record in Camden, New Jersey, for Victor, playing the popular intermezzo Narcissus. He would have a chance to reinterpret the number at the same studio 10 years later.

Once he was 18, Phil took off south for New York City and accidently found work as a piano salesman and demonstrator for the world famous Wannamaker's Department Store. He reportedly had ducked into the store during a heavy snow storm, found the pianos, and played one to pass the time. This casual event resulted in a job offer on the spot. Given that the original Philadelphia Wannamaker's housed the great pipe organ taken from the Cascades building of the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, it is not hard to imagine that Phil may have ventured there on one or more occasions for performances on the instrument, given his prior instruction. He was listed on his 1917 draft record as employed by John Wannamaker on Broadway.

Given the wide range of experiences and training Phil had, he still lack focus in terms of the genre of music he would soon specialize in, popular dance fields. He was obviously eager to work, however, and in addition to occasional small concerts Phil served as accompanist and sole pianist for Marie Sundelius, Reinald Werrenrath, Rafelo Diaz, John Barnes Wells and other celebrated singers. These relationships lasted into the early 1920s as he continued to find his niche. He also toured with Wells early in 1921. But even before that good fortune fell into his lap.

He was obviously eager to work, however, and in addition to occasional small concerts Phil served as accompanist and sole pianist for Marie Sundelius, Reinald Werrenrath, Rafelo Diaz, John Barnes Wells and other celebrated singers. These relationships lasted into the early 1920s as he continued to find his niche. He also toured with Wells early in 1921. But even before that good fortune fell into his lap.

He was obviously eager to work, however, and in addition to occasional small concerts Phil served as accompanist and sole pianist for Marie Sundelius, Reinald Werrenrath, Rafelo Diaz, John Barnes Wells and other celebrated singers. These relationships lasted into the early 1920s as he continued to find his niche. He also toured with Wells early in 1921. But even before that good fortune fell into his lap.

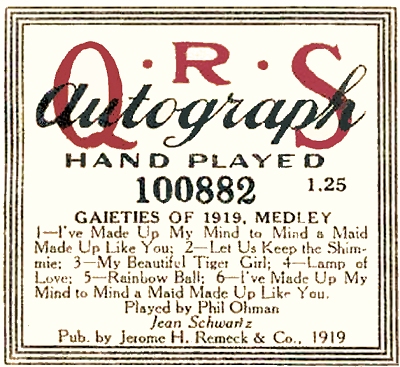

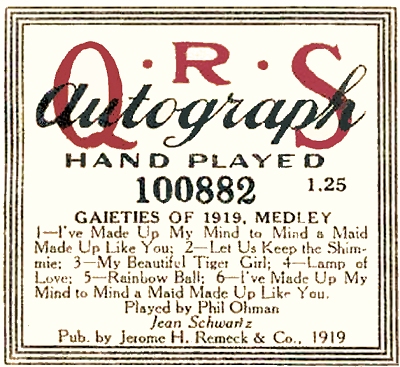

He was obviously eager to work, however, and in addition to occasional small concerts Phil served as accompanist and sole pianist for Marie Sundelius, Reinald Werrenrath, Rafelo Diaz, John Barnes Wells and other celebrated singers. These relationships lasted into the early 1920s as he continued to find his niche. He also toured with Wells early in 1921. But even before that good fortune fell into his lap.Ohman's big break and introduction into show business came in early 1919 when he secured a position at QRS arranging and recording piano rolls. That summer he met up with another young performer and arranger who had been recording some popular music rolls for Rythmodik and Ampico, and was now employed by QRS, Victor Arden (a.k.a. Lewis Fuiks). They found that they had similar backgrounds, abilities and points of view concerning performance, and neither lacked the energy to explore new ways to interpret tunes. The duo quickly found that they could produce some amazing roll arrangements with little effort, and were soon inseparable. Their first QRS rolls started to appear within weeks of Arden joining the firm. Ohman sketched out the general direction of what they would play without full notation, then they would record with Arden in the bass and Ohman in the treble.

One critic who observed them up close found Ohman to be the "wag and clown of the pair," calling Arden the "serious minded, painstaking musician." While a slightly imbalanced point of view, Ohman's humor was more likely to come out in his playing, even during serious classical recitals that he accompanied. Both quickly became celebrities both in and outside the circle of jazz performers, and the public proved to be thirsty for their duet piano rolls. In addition to his QRS work, Phil was also a solo pianist at the Capitol Theatre in Manhattan for some time, which would lead him into a job with great radio exposure in the coming years.

While a slightly imbalanced point of view, Ohman's humor was more likely to come out in his playing, even during serious classical recitals that he accompanied. Both quickly became celebrities both in and outside the circle of jazz performers, and the public proved to be thirsty for their duet piano rolls. In addition to his QRS work, Phil was also a solo pianist at the Capitol Theatre in Manhattan for some time, which would lead him into a job with great radio exposure in the coming years.

While a slightly imbalanced point of view, Ohman's humor was more likely to come out in his playing, even during serious classical recitals that he accompanied. Both quickly became celebrities both in and outside the circle of jazz performers, and the public proved to be thirsty for their duet piano rolls. In addition to his QRS work, Phil was also a solo pianist at the Capitol Theatre in Manhattan for some time, which would lead him into a job with great radio exposure in the coming years.

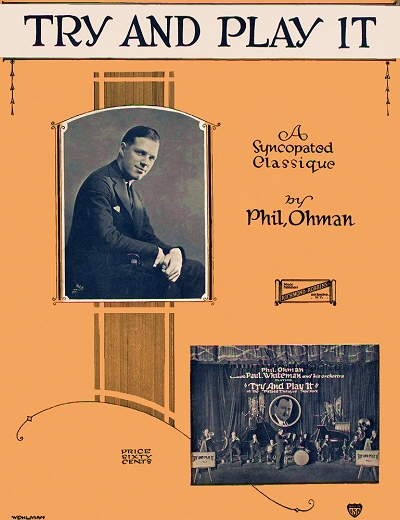

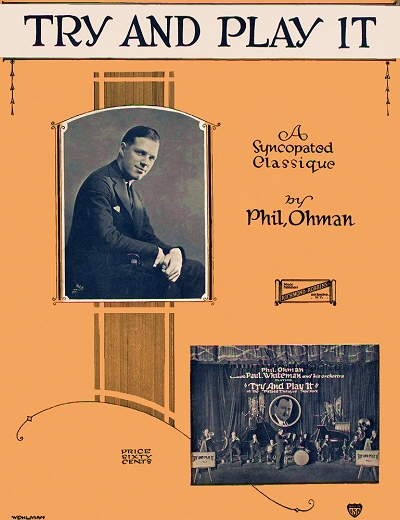

While a slightly imbalanced point of view, Ohman's humor was more likely to come out in his playing, even during serious classical recitals that he accompanied. Both quickly became celebrities both in and outside the circle of jazz performers, and the public proved to be thirsty for their duet piano rolls. In addition to his QRS work, Phil was also a solo pianist at the Capitol Theatre in Manhattan for some time, which would lead him into a job with great radio exposure in the coming years.The QRS gig was going well for both of them, together and separately. Phil appeared in the 1920 census simply as working for a musical company, which could be QRS or any of the record labels he and Arden were recording on. However, Ohman got married on September 4, 1920, to Mildred Stolpe, a woman who had an identical parental heritage to his, her father from Sweden and mother from Illinois. Now with a wife, Ohman needed some additional income to pay the bills, so he started to accompany both classical and popular singers on recordings. This led to a position in the fast-rising orchestra of Paul Whiteman, the so-called "King of Jazz." Not able to keep all his positions, Ohman had to quit QRS and break up the duo for a while. But before he left, he turned out three amazing novelty tunes in 1922, of which the tauntingly-named Try and Play It was one of the best. In 1923 pianist/composer Arthur Schutt would make a signature recording of the piece during a London recording session. In his absence, QRS artist Max Kortlander played many great duets with Arden on piano roll and a pair of them on records.

While the job with Whiteman was both good for his exposure as well as making connections, Ohman realized, as did Arden, that it was less fulfilling than their duo performances. So after a year or so he quit Whiteman's orchestra - which would soon premiere George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue - and concentrated on local gigs with Arden. They built their repertoire playing in clubs in midtown Manhattan, particularly on 52nd Street, and went into the studio to record more frequently as a duo. Among their eclectic choices were the 1888 galop Dance of the Demons by multi-piano composer Eduard Holst, and two popular piano rags, Maple Leaf Rag and the song version of Canadian Capers. They were also one of the earliest piano duos to appear on radio as early as 1922, and were featured in one notable broadcast on wireless Chicago station KYW on April 11, 1925, for an estimated audience of 300,000 listeners. Phil worked separately for some time on the popular Sunday night show [later moved to Monday] Roxy and His Gang starring entertainer Samuel L. Rothafel, which started broadcasting from the Capitol Theatre in 1923. He brought Arden on for occasional appearances on the show.

So after a year or so he quit Whiteman's orchestra - which would soon premiere George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue - and concentrated on local gigs with Arden. They built their repertoire playing in clubs in midtown Manhattan, particularly on 52nd Street, and went into the studio to record more frequently as a duo. Among their eclectic choices were the 1888 galop Dance of the Demons by multi-piano composer Eduard Holst, and two popular piano rags, Maple Leaf Rag and the song version of Canadian Capers. They were also one of the earliest piano duos to appear on radio as early as 1922, and were featured in one notable broadcast on wireless Chicago station KYW on April 11, 1925, for an estimated audience of 300,000 listeners. Phil worked separately for some time on the popular Sunday night show [later moved to Monday] Roxy and His Gang starring entertainer Samuel L. Rothafel, which started broadcasting from the Capitol Theatre in 1923. He brought Arden on for occasional appearances on the show.

So after a year or so he quit Whiteman's orchestra - which would soon premiere George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue - and concentrated on local gigs with Arden. They built their repertoire playing in clubs in midtown Manhattan, particularly on 52nd Street, and went into the studio to record more frequently as a duo. Among their eclectic choices were the 1888 galop Dance of the Demons by multi-piano composer Eduard Holst, and two popular piano rags, Maple Leaf Rag and the song version of Canadian Capers. They were also one of the earliest piano duos to appear on radio as early as 1922, and were featured in one notable broadcast on wireless Chicago station KYW on April 11, 1925, for an estimated audience of 300,000 listeners. Phil worked separately for some time on the popular Sunday night show [later moved to Monday] Roxy and His Gang starring entertainer Samuel L. Rothafel, which started broadcasting from the Capitol Theatre in 1923. He brought Arden on for occasional appearances on the show.

So after a year or so he quit Whiteman's orchestra - which would soon premiere George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue - and concentrated on local gigs with Arden. They built their repertoire playing in clubs in midtown Manhattan, particularly on 52nd Street, and went into the studio to record more frequently as a duo. Among their eclectic choices were the 1888 galop Dance of the Demons by multi-piano composer Eduard Holst, and two popular piano rags, Maple Leaf Rag and the song version of Canadian Capers. They were also one of the earliest piano duos to appear on radio as early as 1922, and were featured in one notable broadcast on wireless Chicago station KYW on April 11, 1925, for an estimated audience of 300,000 listeners. Phil worked separately for some time on the popular Sunday night show [later moved to Monday] Roxy and His Gang starring entertainer Samuel L. Rothafel, which started broadcasting from the Capitol Theatre in 1923. He brought Arden on for occasional appearances on the show.The performances were a sensation, and Broadway soon discovered them as well, knowing that they would be an additional draw to certain shows. The use of dual pianists or pianos was not new on Broadway, but their reputation was about as solid as their first Broadway employer/collaborator, Gershwin himself. So it was that they co-led the pit orchestra for Lady Be Good in 1924. According to the January 3, 1925 edition of The Music Trade Review:

An interesting anecdote relative to the two Story & Clark small grands being used by Phil Ohman and Victor Arden in the musical show 'Lady Be Good,'... was told this week by L. Schoenewald, New York district manager of the Story & Clark Piano Co. 'The original arrangement was that two of our pianos were to be used by the show when it opened in Philadelphia... but an error on the part of the stage carpenters resulted in building of the special moving platform too small to hold them. Although they had requested Story & Clark grands, Ohman and Arden were compelled to play their duet numbers on two 4 feet 8 grands of different makes during the Philadelphia engagement.

They were not satisfied with the tone of these pianos, so on coming to New York Victor Arden prevailed on the management to enlarge the platform to hold our 5 feet 2 inch grands. It has afforded the Story & Clark Piano Co. much pleasure to realize that our pianos are held in such esteem by two such talented pianists as Phil Ohman and Victor Arden.

|

Gershwin started what would become a popular trend throughout the remainder of the 1920s and into the 1930s, supported in the end by the economy of having two pianists and requiring less orchestra personnel. This trend was noted in The Music Trade Review of July 16, 1927, in the following excerpt:

Piano Duos Featured in Both Productions and Over the Radio as Well as in Moving Picture Theatres—Wide Variety of Effects Obtainable

A FORM of presentation of popular numbers which during the past season has reached a new point of popularity is the piano duo as exemplified by nearly half a dozen teams of pianists featured in the orchestra pits of the leading musical comedy successes. The use of specially arranged numbers for four hands is a practice older than jazz itself and originated many years ago in the recording studios of the pioneers in music roll making. Since that time, with the development of the augmented dance orchestra, the employment of two pianos has followed the trend of the day and the sparkle of special choruses for the pianists in skillful teamwork has become one of the bright spots of an evening at the dance floor or cabaret.

About three years ago Phil Ohman and Victor Arden, seasoned recording pianists, were featured in a specialty in "Lady, Be Good," a George Gershwin musical show. This started things for the theatrical presentation of piano duos and the same team appeared the following year in the pit of the Gershwin show, "Tip Toes." Here the effect was more impressive than in the previous engagement, where they had appeared on the stage but only for a short time. In the second show the two pianos were an integral part of the orchestra during the entire evening.

Anyone susceptible at all to rhythmic and harmonic effects in popular music will not soon forget the thrill of hearing the arpeggio passages of Phil Ohman on the upper register of his piano in the number, "That Certain Feeling," of Gershwin. The pianists had carefully gone over the entire score with the composer in rehearsals and every place that afforded a pianistic "break" or embellishment was so treated. The result was a score far more brilliant and individual than is customarily heard from the orchestra pit and a new custom was started...

But the spread of popularity of the piano due has not ended in the theatre. The radio, too, has developed favorites in four-hand interpretation of the latest hits.

After six years with QRS, Phil moved on to the Aeolian company to cut Duo-Art reproducing piano rolls, effectively ending the run of Ohman and Arden piano rolls. As noted in the July 11, 1925 edition of the trade magazine Presto: "Phil Ohman, most brilliant of all exponents of 'pianistic jazz,' has [contracted] with the Aeolian Company to record his playing of the newest popular hits exclusively for the Duo-Art Reproducing Piano. This artist is more than a player of jazz music. He is an "all-round" pianist of exceptional skill, dexterity, musical understanding and constructive cleverness. His training as a pianist is founded upon long study of the classics. But Ohman's chief characteristic as a jazz soloist is his astounding technical brilliance. He was among the first to be hailed as a real virtuoso of dance music... For the Duo-Art, Ohman will record both dance music and popular ballad selections." Ohman must have had quite a backlog of recordings with QRS since "new" rolls appeared on that label as late as December, 1925.

His training as a pianist is founded upon long study of the classics. But Ohman's chief characteristic as a jazz soloist is his astounding technical brilliance. He was among the first to be hailed as a real virtuoso of dance music... For the Duo-Art, Ohman will record both dance music and popular ballad selections." Ohman must have had quite a backlog of recordings with QRS since "new" rolls appeared on that label as late as December, 1925.

His training as a pianist is founded upon long study of the classics. But Ohman's chief characteristic as a jazz soloist is his astounding technical brilliance. He was among the first to be hailed as a real virtuoso of dance music... For the Duo-Art, Ohman will record both dance music and popular ballad selections." Ohman must have had quite a backlog of recordings with QRS since "new" rolls appeared on that label as late as December, 1925.

His training as a pianist is founded upon long study of the classics. But Ohman's chief characteristic as a jazz soloist is his astounding technical brilliance. He was among the first to be hailed as a real virtuoso of dance music... For the Duo-Art, Ohman will record both dance music and popular ballad selections." Ohman must have had quite a backlog of recordings with QRS since "new" rolls appeared on that label as late as December, 1925.During this period, while Arden and Ohman were under contract to Brunswick Records from 1923 to 1927, they were involved with that company's transition from acoustic to electrically-recorded discs in 1925. As a result, several of their tracks, as well as many done by Phil accompanying other musicians and singers, were done with both acoustic horns and then microphones in the same session, and others required three or four sessions over as many months to render satisfactory results. Brunswick master logs show at least four attempts at the disc containing Operatic Favorites and Waltzes of the Past between May and August 1925, possibly due to issues with properly capturing not only the pianos, but also the xylophone or vibraphone of George Hamilton Green who was playing with them. By late 1925 all of Brunswick's releases, as well as most by other record companies, were electrically recorded.

Ohman and Arden's first Broadway success would be followed by more Gershwin shows such as Tip Toes in 1925, Oh, Kay in 1926, and Funny Face in 1927. Other shows included Treasure Girl in 1928, both Spring is Here and Heads Up in 1929.  In between the Broadway shows they recorded and performed on the road on the vaudeville circuits. Among the labels Ohman and Arden appeared on were Columbia, Victor (soon to be RCA Victor) and Gramophone.

In between the Broadway shows they recorded and performed on the road on the vaudeville circuits. Among the labels Ohman and Arden appeared on were Columbia, Victor (soon to be RCA Victor) and Gramophone.

In between the Broadway shows they recorded and performed on the road on the vaudeville circuits. Among the labels Ohman and Arden appeared on were Columbia, Victor (soon to be RCA Victor) and Gramophone.

In between the Broadway shows they recorded and performed on the road on the vaudeville circuits. Among the labels Ohman and Arden appeared on were Columbia, Victor (soon to be RCA Victor) and Gramophone.There were several occasions in the years of Arden and Ohman that Phil recorded on his own. One session that was recently brought to light by California performer/historian Frederick Hodges through a discovery by New York bandleader Peter Mintun were two unreleased tracks, possibly done for Brunswick but not fully determined. Broken Glass and Jacquette were not published or even sketched out on a manuscript as far as Hodges knows. Neither piece saw the light of day publicly until late 2008 when Hodges transcribed and recorded these two fine novelties. The reason for their retention is unclear, but since Ohman had a few other projects of his own during the tenure of the team, it seems unlikely that there were any issues in that regard.

It should be noted that when Phil and Victor were billed in any venue that the order of their names did not matter to them, the sign of a solid partnership. They were also sought out in the late 1920s, as many New York acts were, by Warner Brothers for a few Vitaphone sound shorts, one of the first being The Piano Dualists in 1927. They were later seen and heard playing Dancing the Devil Away in the 1930 RKO musical The Cuckoos. Arden turned out many interesting arrangements during the 1920s of dance tunes on record, many sold very cheaply in Woolworths and similar outlets, making his name perhaps even better known than Ohman's.

One of their contemporary critics, Gay Stevens, said the following concerning this formidable duo:

There is not a piano player in the land who, after hearing Ohman and Arden interpret a piece of jazz music on their two pianos, has not wanted to throw his piano out of the window. The keyboard magic of this duo-team has been the inspiration and despair of every real American youngster who sedulously practiced his Czerny with a secret desire to win excited gasps of admiration from the fair young things in his circle by his jazz piano playing.

Arden, Ohman and Kortlander appeared together often for QRS promotions in the mid-1920s, playing live performances of their collective solo and duet piano rolls in addition the occasional trio. While Victor and Phil often performed just with the piano, the Arden-Ohman orchestra was started in 1925, initially for recording but later for both live performance and radio work. It was the latter that gave them their best overall exposure in the late 1920s through the first part of the Great Depression.

For a brief period around 1928, when Arden went to work for the Ampico roll company, fellow roll artist Adam Carroll who was now recording rolls with Arden joined both of them to create a trio for a few performances on radio and for special functions. It was radio that gave Arden and Ohman their best overall exposure in the late 1920s through the first part of the Great Depression.

Ohman was still personally a bit modest about this, as in the 1930 census, living in Manhattan with Mildred and no children, he lists himself simply as a band musician.

|

Realizing that the best possible future for success was on the radio, the most effective medium of the 1930s, the dynamic piano duo re-teamed and hit the airwaves. Arden and Ohman had no issue finding good sponsorship, playing for everything from news programs to two or three numbers advertising toothpaste or fine watches. Some of their musical shows included The Bayer Music Review, The Buick Program, and the landmark American Album of Familiar Music. But the stresses of performance partnership eventually interfered, more on the professional level than on the personal level, and in 1934 Arden and Ohman split to go in different directions, remaining friends. The duo reunited for one more recording session on Brunswick that same year. The following year, Ohman finally joined ASCAP.

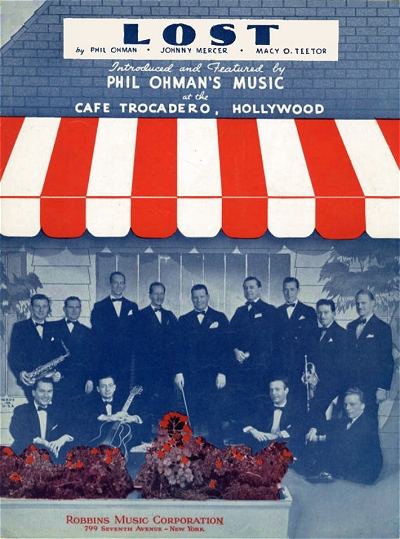

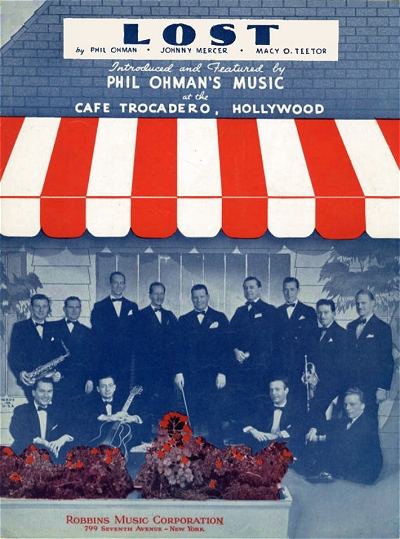

After the Brunswick sessions, Ohman had no trouble finding work with his own orchestra, mostly the remains of the duo's group, and was soon in Los Angeles, California plying Latin and Hawaiian rhythms at the famous Trocadero Nightclub on Sunset Boulevard. Phil and Mildred were located in Hollywood for the 1940 enumeration, living on Hollywood Blvd. in fact. Among his first song collaborators in Hollywood was a young Johnny Mercer who would start Capitol Records in 1942. Their big hit was the song Lost in 1936. Given his new proximity to Hollywood, it wasn't long before Ohman was working with writing or arranging film scores, and even playing for, and eventually in some films, most appearing during the first half of the 1940s. While Ohman did not write many popular songs, concentrating more on performance, he did manage another fine tune with Each Time You Say "Good Bye", a big hit during the Swing Era and beyond. One film in which he was clearly visible was the 1939 film The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, which required a pianist who knew what he was doing on camera. As of the 1940 census taken in Hollywood where Phil and Mildred were residing, he listed himself as a musician-composer working at home.

Along with fellow performers Ray Turner and Oscar Levant, Ohman was one off the most prominent film pianists of the late 1930s through the 1940s. He also formed an orchestra for the 1949 film Million Dollar Weekend which, according to a Stars and Stripes newspaper review, was shot largely at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu, Hawai'i. The reviewer also noted that Ohman was an "authority on Hawaiian Rhythms." Soon after this he retired from films, but still played for radio on occasion over the next few years and made some appearances on Los Angeles television stations. The 1950 census showed Phil to still be an orchestra musician as well. One of his favorite haunts was Players Restaurant on Sunset Boulevard, not far from the Trocadero. Phil died at age 57 from complications of a kidney ailment. He and Mildred did not have any children. His former partner, Victor Arden, followed almost exactly eight years later. While certainly not a prominent figure as a composer, Phil Ohman, as well as Victor Arden, was able to bring alive the music of many other writers during the 1920s and 1930s in a way that still resonates well with us today in its vitality.

Thanks to New Zealand piano roll historian Robert Perry for additional information and clarification on Ohman's career with various piano roll companies, and for the Gay Stevens quote. For more on piano roll artists, please visit him at www.pianola.co.nz. The remaining information was researched by the author in public records, periodicals and recorded media.

Compositions

Compositions