Rube Bloom was the third of five children born in New York City to Russian immigrants Abraham M. Bloom and Fannie J. Kaplan. His siblings included Sidney Joseph (9/4/1898 - listed as Joseph in the 1900 census), Helen Ann (3/1900 - listed as Annie in the 1900 census), Harry (c.1905) and Milton (1906). Abraham came to the United States in 1888, followed by Fannie in 1895, and they were married on Noveber 17, 1897. He was listed as a painter in a factory in the 1900 and 1910 Federal enumerations.  There has been some confusion over Rube's true birth name. While sometimes cited as Rueben, it is more consistently spelled Rubin or Ruben in early public records, not an uncommon spelling among Russian Jews.

There has been some confusion over Rube's true birth name. While sometimes cited as Rueben, it is more consistently spelled Rubin or Ruben in early public records, not an uncommon spelling among Russian Jews.

There has been some confusion over Rube's true birth name. While sometimes cited as Rueben, it is more consistently spelled Rubin or Ruben in early public records, not an uncommon spelling among Russian Jews.

There has been some confusion over Rube's true birth name. While sometimes cited as Rueben, it is more consistently spelled Rubin or Ruben in early public records, not an uncommon spelling among Russian Jews.Details of Rube's years growing up are scant, including whether or not there was a piano in the family's home on Stockton Street. Whatever the circumstance, he quickly latched on to the piano, and it has been said that with virtually no formal training managed not only to learn to play, but to tackle the difficult concepts of harmony and theory on his own. A couple of later articles claimed that he had been, in fact, privately trained in composition and piano performance at some point, so the "no training" story is somewhat suspect, given his level of talent. It is unclear as to whether he eventually learned to transcribe his pieces or just used an arranger to do it for him. His obituary insisted that he composed directly on the piano and worked with arrangers to create both piano scores and orchestrations.

By the age of 17 Rube was out working the vaudeville houses of Manhattan, sometimes touring a bit beyond, as a rock solid staple of any company he was in, usually working as an accompanist during this period. The 1920 census shows Rube as a pianist in vaudeville. His father was now a shoemaker. Note that many historians insist his name was pronounced "Ruby" but at least one recording held by pianist Peter Mintun has it pronounced as "Rube" in his own voice. The music press helps confirm the former as they often used "Ruby" in print.

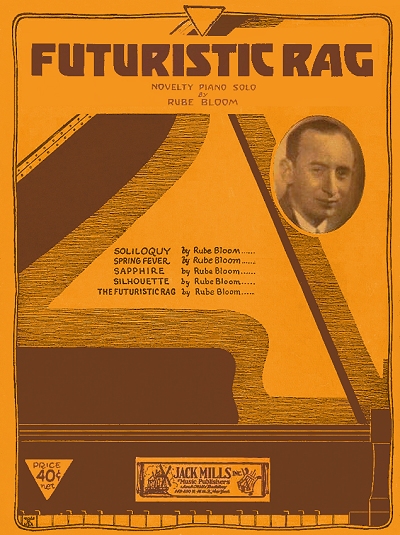

While he was making his way from the vaudeville stage to the band stage, Bloom started concocting his own compositions. The first one, Indiana Moon, was a simple song, but it was followed by That Futuristic Rag, which was a launching point for his career as a composer. It shows a penchant for moving whole note harmonies that somehow remain congruous with the key signature. While the term "rag" was quickly become stale in the early 1920s, the format was actually advancing, relabeled as novelty piano. Bloom did not move in the same dynamic direction as Zez Confrey or Frank Banta, but this work stood up to them rather well. He would not record it until six years after its initial publication. That Futuristic Rag is still played nearly a century later, quite notably by the brilliant Frederick Hodges.

Rube's reputation quickly grew, and as the jazz age began he found more work as a band pianist.

Over the next decade he would play, and often record with many very reputable musicians and a number of fine jazz groups. Among those in his circle were other competent pianists, notably the brilliant Arthur Schutt, and musicians that would reach both fame and defeat, most notably composer and cornetist Bix Beiderbecke. The groups he played for include The Captivators, Pinkie's Birmingham Five, Joe Venuti and his Orchestra, Hottentots, Joe Venuti's Four/Five/Six, Ray Miller's Orchestra, The Cotton Pickers, The Washingtonians, Arkansas Travelers, The Red Heads, Jay C. Flippen and his Gang, The Melody Sheiks, The Tennessee Tooters, Lee Morse and her Bluegrass Boys, and Ben Selvin and his Orchestra.

|

In addition, Rube was frequently tapped as an accompanist, a skill he refined during his vaudeville days. In the recording world breaking color barriers did not have the same impact as it did for live performances, so he got to work with some very fine black musicians, which further helped develop his playing and composition style in more of an African-American direction. Among the singers or instrumental soloists he backed, both jazz and classical, were Ruth Etting, Annette Hanshaw, Ethel Waters, Martha Copeland, guitarist Eddie Lang, Arthur Fields, Peggy English and The Kelly Sisters. The selected discography included here focuses on his feature and solo work, but his total easily tops sixty sides.

For his first studio session at Gennet Records in 1924, Rube backed Beiderbecke, trombonist Miff Mole, and saxophonist Frankie Trumbauer for two tracks. One of them, Flock O' Blues, was his own composition, which later became known as the Carolina Stomp. It was said that Bix wanted to call the group the Davenport Six, honoring his home town in southeastern Iowa. However, Miff got the engineer to write down Sioux City Six because it was located at the extreme opposite end of the state. The band only recorded those two sides, but those takes still resonate with their obvious collective talent today. As for the Carolina Stomp version, upon its publication in 1925 it received some good press in The Music Trade Review of October 31:

Rube Bloom, who plays a wicked piano, has just placed with the Triangle Music Co. his latest effort entitled "Carolina Stomp." Joe Davis, who does all the angling for the Triangle, says that twenty-four hours after he took the tune he set the number for a Victor and Columbia recording. The Charleston Trio is making it next week for the Victor, and Fletcher Henderson and His Band is making it for the Columbia. A special dance orchestration by Elmer Schoebel will be ready within the next ten days. This number looks like a Triangle success.

From late 1925 to early 1926, Rube further made a name for himself recording with the Hottentots (one of many groups using that name). Along with Mole, the group featured trumpeter Red Nichols who was headed for his own fame in the jazz world. One of their finer takes was on the Chinese Blues, penned by yet another future piano jazz star, Thomas "Fats" Waller. He also made a brief entry into the world of piano rolls, cutting a number of popular pieces in his own style for the Aeolian company on their Aeolian and Mel-O-Dee lines from late 1925 through late 1927. But there were two other pieces he wrote and recorded in early 1926 that helped to define who Rube Bloom was to the music world.

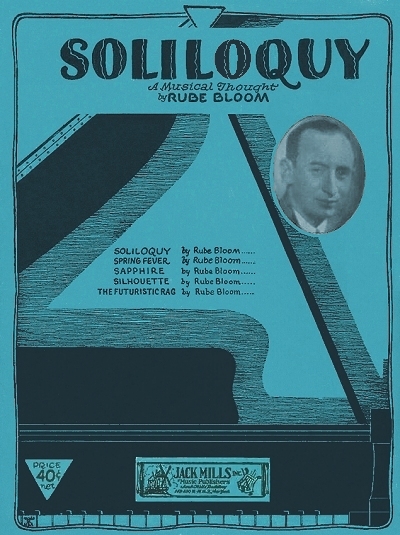

Encouraged by the response to his playing and his earlier works and by Triangle Music publisher Joe Davis, Rube created two more fine progressive novelties in 1926. Spring Fever was an ambitious foray into that world, and was soon covered by a number of artists, including Bloom himself, and an early recording by Ray Turner who would help revive the genre in the 1950s. But it was Soliloquy: A Musical Thought that would stand as one of Rube's finest and most introspective piano solos, both in print and on record. It echoes some of the fine work he was doing as an accompanist for singer Ruth Etting, capturing elements of popular song (a paraphrase of My Mammy in one section) with the delicacy of parlor intermezzos. He would record the piece on a piano roll and at least three times on record over the next year along with Spring Fever.

They were initially published by Davis through Triangle Music, but even after that catalog was acquired by publisher Jack Mills, both remained good sellers in the Mills catalog for many years. Many publishers also encouraged many novelty piano stars to create method books to engage the public. Bloom's first, published by Alfred Music in 1926, was 100 Jazz Breaks for Piano, giving the consumer a glimpse into the methods used by many jazz pianists to creatively "fill in the gaps" in the middle of a repeated chorus. Soliloquy also was published in a popular orchestral version, and was performed frequently over the next few years. Rube was called on to present it, with the orchestration, at a Modern Jazz Concert on February 19, 1926 at Symphony Hall in Boston, Massachusetts. The program was hosted by Columbia Records artist and orchestra leader Leo Reisman, and featured composer Ferdé Grofé, plus black trumpeter Johnny Dunn playing some blues numbers.

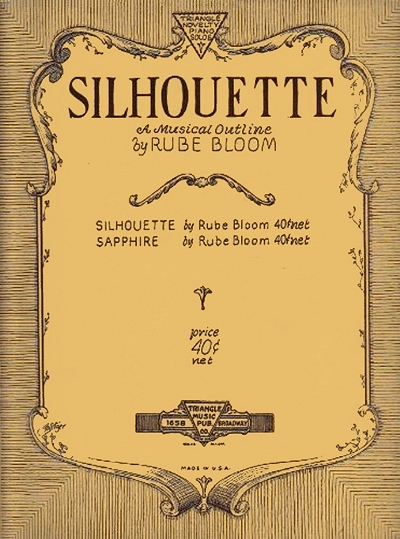

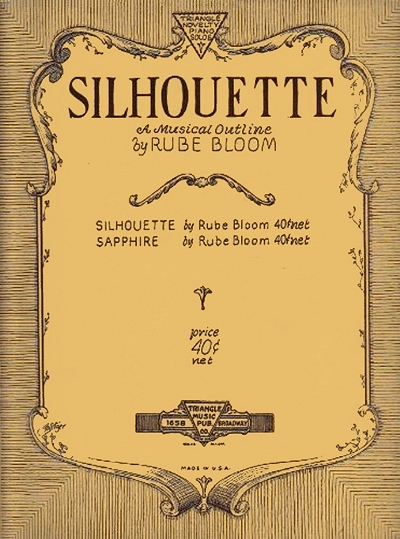

A follow-up to his two fine novelties was called for, and Bloom did not disappoint. In 1927 he crafted two more, Sapphire: A Musical Gem and Silhouette: A Musical Outline.  The hype presented by publisher Joe Davis in the trades that April, he said "that these two numbers have unusual possibilities, and are great follows-ups for the previous novelties by the same writer, called 'Spring Fever' and 'Soliloquy.'" All four would play an unusual but important role in copyright law in years to come.

The hype presented by publisher Joe Davis in the trades that April, he said "that these two numbers have unusual possibilities, and are great follows-ups for the previous novelties by the same writer, called 'Spring Fever' and 'Soliloquy.'" All four would play an unusual but important role in copyright law in years to come.

The hype presented by publisher Joe Davis in the trades that April, he said "that these two numbers have unusual possibilities, and are great follows-ups for the previous novelties by the same writer, called 'Spring Fever' and 'Soliloquy.'" All four would play an unusual but important role in copyright law in years to come.

The hype presented by publisher Joe Davis in the trades that April, he said "that these two numbers have unusual possibilities, and are great follows-ups for the previous novelties by the same writer, called 'Spring Fever' and 'Soliloquy.'" All four would play an unusual but important role in copyright law in years to come.With a busy recording and performance schedule throughout 1927, Bloom had little time for writing much more. His piano career was soaring, yet his personal life was a mystery. Rube was still living with his now-widowed mother and three brothers, although now they were now across the river from Manhattan in Brooklyn on Brooklyn Avenue in a larger home. Even though their sister had married, the brothers remained bachelors into the 1930s. Harry had become a lawyer, and Sidney was in the advertising business. Milton, on the other hand, followed his big brother into music as a trumpeter. No specific information was located to link them playing together in the same group or on a recording, but given the jazz world in New York City, there remains that possibility. Milton eventually moved to Los Angeles where he played and taught music for many years.

In 1928 there was a new group of Bloom compositions to delight fans and vex amateur pianists. His three solo novelties for the year included Fannette, Serenata and Fleur De Lis published by Triangle. In the middle of the year he jumped to two other publishers, one in part because his novelty work was co-composed with two other writers. First was his Modern Jazz Piano Course published by the Robbins firm, a formidable rival to Jack Mills in the piano novelty genre. Then there was a new tune that was noteworthy enough to garner an announcement in the Music Trade Review of August 4, 1928:

The Irving Berlin Standard Music Corp., New York, has recently released its first popular novelty tune, entitled "Jumping Jack," which is showing up well professionally and commercially. This number, written by Rube Bloom in collaboration with Bernie Seaman and Marvin Smolev, has been issued as a piano solo and also in dance orchestration form. "Jumping Jack" has been featured on several coast-to-coast radio hook-ups, and appears to be the type of novelty number which will be long lived. A new edition with lyrics will be off the press shortly and should open an additional field for the song.

It would go on to be included in the 1929 film The Show of Shows.

Rube went to England and Europe late in the summer for a brief performance tour, returning in September 1928. In an interview from that time he predicted that "a distinctive national school of music was being born in this country." Rube was certain that the United States would someday be the "musical center of the world. In the years to come there will arise a distinctive American music. Now it is in the embryonic stage. Music in the truly American idiom is 'blues,' which, of course, is Negroid in origin. Negro spirituals and 'blues' are practically all our worthwhile folk music... But I think of music that is American in the future without being Negroid, but individual, expressive and representative of this country as a unit."

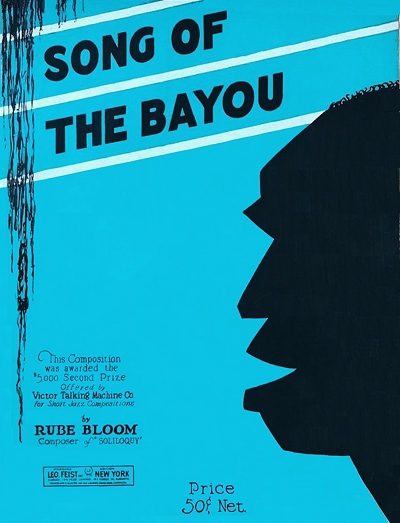

Then another important event helped to increased Bloom's exposure as a composer, assuring him a bright future in that regard. The Victor Talking Machine Company held an open "$10,000 prize competition for the best concert composition within the playing scope of the American dance or jazz orchestra." Before the closing on October 29th, 1928, hundreds of entries were submitted. At the same time they were also offering a $25,000 prize for the best symphonic composition, a first in the music industry. The results were announced on December 28, 1928, and reported the next day in The Music Trade Review:

ON Friday evening of this week the Victor Talking Machine Co. announced the winners of the prizes offered for short jazz compositions within the scope of the small American jazz or dance orchestra, the prizes being the largest ever offered for compositions of that character. The official announcement was made at a dinner given at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel at which John Philip Sousa presided, and the prizes were presented by Edward E. Shumaker, president of the Victor Talking Machine Co., after S. L. Rothafel, chairman of the Judges' Committee, had described the contest and the manner in which it was conducted. Thomas Griselle of Mount Vernon, N. Y., was awarded the first prize of $10,000 for his "Two American Sketches," and Rube Bloom of Brooklyn, N. Y., was named as winner of the second prize of $5,000 for his composition, "Song of the Bayou." The playing time of each number is less than five minutes.

The contest, which was announced last May, was open only to American citizens, and was designed by the Victor Co. to encourage the art of musical composition in America. Prizes were offered for the two best compositions "within the playing scope of the American dance, jazz, or popular concert orchestra, not hitherto published or performed in public." Hundreds of manuscripts were received from every section of the country, many of them being of such excellence that the judges' committee required two months to reach their final decision...

Rube Bloom, winner of the second prize, is a native of New York. His study has been almost entirely with private teachers. During the past three years he has published several compositions, best known of which is "Soliloquy," a number that has been successfully played by several concert jazz orchestras. Other published works are "Sapphire," "Silhouette," "Serenata," and "'Fleur de Lis." Both prize compositions were broadcast over a large network of stations by a Victor orchestra under the direction of Nathaniel Shilkret...

A Victor record with both compositions performed by Shilkret was also offered to the public on December 29th. Both winners were able to choose the publisher they wanted to release the work, and Rube picked the firm of Leo Feist. In short order, Song of the Bayou, published as a piano solo and as a song with lyrics by Bloom, became a minor hit. As a result, Rube was kept busy with appearances in both the US and Europe during this period. There were apparently no recordings made of him as a soloist or accompanist in 1929, with the exception of a few minor band sides. In the 1930 enumeration he is shown living in Brooklyn with his mother and three brothers, listed as a musician/pianist. Within a year or two he would move out and live on his own at 1025 St. John's Place, still in Brooklyn.

In spite of the exposure for his earlier novelties, now being published by the combined Triangle/Jack Mills Company, Rube was still riding on the fame from his Song of the Bayou win. To that end, at the close of 1929 he formed a band that was destined for recording gigs only, Rube Bloom and His Bayou Boys. Starting in January they recorded a total of six released sides by May,  and some jazz historians regard these as some of the hottest records from the early part of the Great Depression. When you consider the lineup, that is no accident or understatement. Along with Rube on the piano, he engaged Manny Klein on trumpet, Tommy Dorsey on trombone, Benny Goodman on clarinet, Adrian Rollini on bass saxophone, Stan King on drums and vocalist Roy Evans at the microphone. They never performed live or on the radio.

and some jazz historians regard these as some of the hottest records from the early part of the Great Depression. When you consider the lineup, that is no accident or understatement. Along with Rube on the piano, he engaged Manny Klein on trumpet, Tommy Dorsey on trombone, Benny Goodman on clarinet, Adrian Rollini on bass saxophone, Stan King on drums and vocalist Roy Evans at the microphone. They never performed live or on the radio.

and some jazz historians regard these as some of the hottest records from the early part of the Great Depression. When you consider the lineup, that is no accident or understatement. Along with Rube on the piano, he engaged Manny Klein on trumpet, Tommy Dorsey on trombone, Benny Goodman on clarinet, Adrian Rollini on bass saxophone, Stan King on drums and vocalist Roy Evans at the microphone. They never performed live or on the radio.

and some jazz historians regard these as some of the hottest records from the early part of the Great Depression. When you consider the lineup, that is no accident or understatement. Along with Rube on the piano, he engaged Manny Klein on trumpet, Tommy Dorsey on trombone, Benny Goodman on clarinet, Adrian Rollini on bass saxophone, Stan King on drums and vocalist Roy Evans at the microphone. They never performed live or on the radio.Unfortunately, the unfolding fiscal crisis triggered by the Wall Street failure created a substantial dent in the recording industry, and the public was migrating to radio, which was a much less expensive and more current form of entertainment. Revenue from radio appearances evidently became necessary for Rube because an early 1929 Broadway gossip column noted that he had dropped his $5,000 winning into Wall Street, obviously not knowing what would transpire in October. Victor tried made the most of Bloom's radio appearances, but it was not enough to stave off the collective woes of the country's financial crisis which quickly put many record and piano roll companies out of business.

Fortunately Bloom had been working in radio since 1927, and was becoming increasingly familiar to listeners who could receive the New York stations, including WNAC and WABC. There were frequent advertisements in the papers throughout 1929 of his performances of Song of the Bayou and his other novelty works, so he was able to weather the storm relatively well. There was also a minor 1930 hit which really helped to launch his career as a songwriter. Rube had collaborated on a few tunes before, but The Man From the South (With a Big Cigar in His Mouth) penned with Harry Woods was the first that had life in the world of popular music. He also started a long collaboration with lyricist Ted Koehler with Puttin' It On For Baby that same year. They would improve on their skills and titles in short order.

While recordings all but shut down for groups like Rube's and radio even let up a little, Bloom was still highly regarded, and was commissioned at the suggestion of Shilkret to complete a special composition for the somewhat ill-timed 1931 opening of the ostentatious new Empire State Building. A passage concerning this was reprinted in Joun Tauranac's 1997 book The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark:

The contribution of the oil industry to the erection of the Empire State Building was 'strikingly dramatized' when a Mobiloil Concert hour was broadcast from the Empire State Building over NBC soon after the building opened, in June 1931. The drama hinged around the part played by Mobil in furnishing the oil that kept the machinery for building the great structure running smoothly. The keynote of the program was the orchestra's rendition of Rube Bloom's "Manhattan Skyscraper," a composition said to have been inspired by the rising tower of the Empire State Building. Nathaniel Shilkret led the orchestra in playing Bloom's new piece, which was dedicated to Shilkret.

While there was a lack of recording activity from mid-1930 to late 1934, there was no lack of creative composition. In 1931 Rube released Moods: A Modern Piano Suite, which consisted of five different "moods." They were simply named - Metropolitan, Valse Petite, Gypsy, Blues and Primitive - with each one musically describing their respective title. There were a few other instrumentals that year, including Spring Holiday and Aunt Jemima's Birthday but Bloom also began working with a few fairly well known lyricists, putting some songs into circulation. There were no hits at that time, but his name did sell a few copies here and there.

They were simply named - Metropolitan, Valse Petite, Gypsy, Blues and Primitive - with each one musically describing their respective title. There were a few other instrumentals that year, including Spring Holiday and Aunt Jemima's Birthday but Bloom also began working with a few fairly well known lyricists, putting some songs into circulation. There were no hits at that time, but his name did sell a few copies here and there.

They were simply named - Metropolitan, Valse Petite, Gypsy, Blues and Primitive - with each one musically describing their respective title. There were a few other instrumentals that year, including Spring Holiday and Aunt Jemima's Birthday but Bloom also began working with a few fairly well known lyricists, putting some songs into circulation. There were no hits at that time, but his name did sell a few copies here and there.

They were simply named - Metropolitan, Valse Petite, Gypsy, Blues and Primitive - with each one musically describing their respective title. There were a few other instrumentals that year, including Spring Holiday and Aunt Jemima's Birthday but Bloom also began working with a few fairly well known lyricists, putting some songs into circulation. There were no hits at that time, but his name did sell a few copies here and there.Bloom either took a break over the next couple of years, or had trouble finding much more than occasional work on radio, and his output was light. He took a trip to Bermuda in the spring of 1933, but little other activity that was newsworthy. One song, Stay on the Right Side of the Road, was recorded by Bing Crosby, doing well on the radio. In 1934 Rube released a few songs, and at the end of the year recorded his final two known piano solos for Victor, Penthouse Romance and On the Green. Fortunately, some of the best was ahead for him, and he got a second wind in 1935.

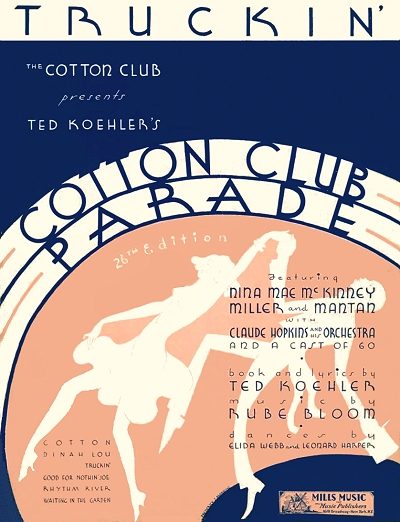

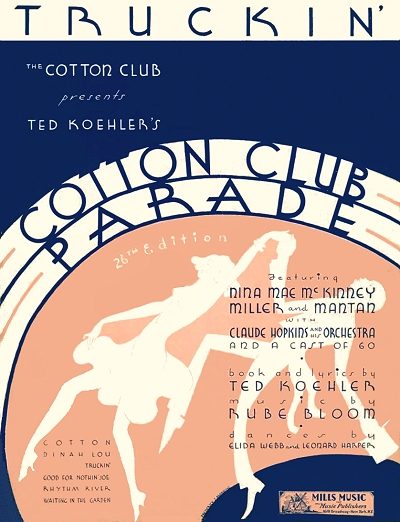

The famous Cotton Club in Harlem, which had long provided black entertainment for white patrons, was undergoing some changes in management (which had reportedly been by crime bosses of the 1920s and 1930s including Owney Madden) and personnel, particularly with the departure of Cab Calloway who had achieved great fame there with Minnie the Moocher and his Hi-De-Ho style. A revue was commissioned in 1935 and lyricist/producer Ted Koehler chose Bloom to write the music. The two had worked together before, and this collaboration on The Cotton Club Parade for 1935 turned out some fine numbers, including Dinah Lou and the instantly catchy Truckin'. Some reviews of the show intimated that it sounded like it was written by a black composer, a compliment to Rube, but this was also in part due to the delivery by the black cast. Truckin' retained its status a popular dance tune for many decades.

The following year, Rube teamed up with a young Johnny Mercer, the singer and eventual founder of Capitol Records, for Lew Leslie's annual "all colored musical revue," this one the Blackbirds of 1936. The show did not yield any notable hits, but it was fairly well received when it opened in May 1936.  The production was staged in London, so Rube played for a while in England in the late spring and early summer of 1936, returning to the United States in late July for a short run at the Gaiety Theater in Manhattan. It was not the end of his collaboration with Mercer, however. This work may have led to Rube writing music underscore and cues for a 1937 film, The Public Wedding. Song of the Bayou was released around the same time with a new set of lyrics added by writer Howard Johnson, and a revised version of Blackbirds was presented in late 1938. Rube's big hit of that year, penned with Koehler, was I Can't Face The Music (Without Singin' the Blues), covered by several artists.

The production was staged in London, so Rube played for a while in England in the late spring and early summer of 1936, returning to the United States in late July for a short run at the Gaiety Theater in Manhattan. It was not the end of his collaboration with Mercer, however. This work may have led to Rube writing music underscore and cues for a 1937 film, The Public Wedding. Song of the Bayou was released around the same time with a new set of lyrics added by writer Howard Johnson, and a revised version of Blackbirds was presented in late 1938. Rube's big hit of that year, penned with Koehler, was I Can't Face The Music (Without Singin' the Blues), covered by several artists.

The production was staged in London, so Rube played for a while in England in the late spring and early summer of 1936, returning to the United States in late July for a short run at the Gaiety Theater in Manhattan. It was not the end of his collaboration with Mercer, however. This work may have led to Rube writing music underscore and cues for a 1937 film, The Public Wedding. Song of the Bayou was released around the same time with a new set of lyrics added by writer Howard Johnson, and a revised version of Blackbirds was presented in late 1938. Rube's big hit of that year, penned with Koehler, was I Can't Face The Music (Without Singin' the Blues), covered by several artists.

The production was staged in London, so Rube played for a while in England in the late spring and early summer of 1936, returning to the United States in late July for a short run at the Gaiety Theater in Manhattan. It was not the end of his collaboration with Mercer, however. This work may have led to Rube writing music underscore and cues for a 1937 film, The Public Wedding. Song of the Bayou was released around the same time with a new set of lyrics added by writer Howard Johnson, and a revised version of Blackbirds was presented in late 1938. Rube's big hit of that year, penned with Koehler, was I Can't Face The Music (Without Singin' the Blues), covered by several artists.In 1939 Bloom and Koehler were again engaged to provide tunes for a special Worlds Fair Edition of the Cotton Club Parade. Opening in February, it received a good amount of press, and yielded a couple more hits, including The Ghost of Smokey Joe and Don't Worry 'Bout Me, that latter one which would have a long shelf life. Day In - Day Out also had decent coverage beyond the show. Some of this publicity reignited interest in Bloom's earlier solo works, so they were kept in circulation by Mills into the 1940s. As of the 1940 enumeration, bachelor Rube was living with his mother Fannie and brother Milton in Brooklyn, listed as a song writer for a music publisher.

From 1940 forward Bloom's work was sparse at best. While not completely retiring at age 38, he did ease up on his activities a bit, playing as an accompanist or in dance bands. He managed one fine number with Mercer in 1940, Fools Rush In (Where Angels Fear to Tread), which was covered by a wide spectrum of artists for many years, including crooners Tony Martin and Frank Sinatra, both already associated with several Bloom numbers. Another, Take Me, with Mack David, became a 1940s hit for the Benny Goodman and Dorsey Brothers' orchestras. Three more songs, this time with Harry Ruby, made it into the 1946 post-war film Wake Up and Dream. Of those, one in particular became a standard for both singers and jazz musicians, Give Me the Simple Life. While there were no more big hits to come from his hand, Bloom put out a handful of works with other lyricists over the next 15 years, culminating with Everybody's Twistin' composed with Koehler during the twist craze of 1962.

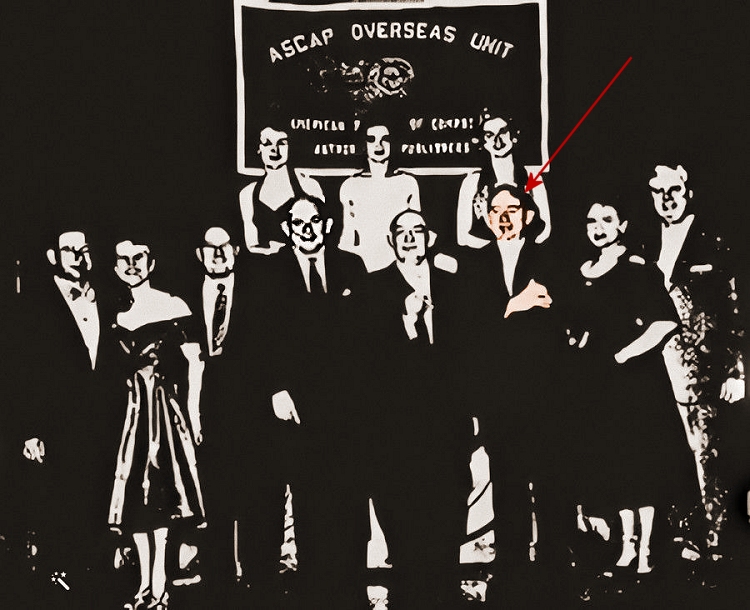

The United States Government teamed up with ASCAP in 1955 to sponsor an overseas tour to entertain the troops stationed around the world, particularly in Germany, France and North Africa. Rube played in several locations during this trip, which was both for morale and publicity. However, his style of music, which enjoyed yet another view during the first ragtime revival of the early 1950s, was quickly being overtaken by the upsurge of more youthful forms, most notably rhythm and blues, and rock and roll.

In spite of a few more pieces, he mostly retired after 1956, and turned out a couple of books on piano method.

|

Rube was, however, involved in a lawsuit that had an impact on copyright law, particularly on the topic of whether renewal was the right of the incumbent owner or should be open game. His suit was led by well-known music lawyer Lee Eastman, the father of Linda Eastman who would eventually marry Paul McCartney, who also hired Eastman to secure rights to his own work. As noted in the May 19, 1956 of Billboard:

Bloom Sues Mills on Copyright Renewals [Lee Eastman] last week filed suit here [New York City] in behalf of client songwriter Rube Bloom against Mills Music for a declaratory judgment on copyright renewal rights for four of his tunes... "What happened in the first 28 years [of copyright] doesn't matter" said Eastman... In the Bloom case, Eastman... is taking the position that Congress intended the copyright renewal "should be a subject of independent action," as opposed to the current pattern wherein Eastman contends) a writer signs away his renewal rights on "printed pro forma forms which were not the subject of negotiation or discussion with respect to renewal copyright of any kind whatsoever."

Eastman had presented a similar case for Hoagy Carmichael and his composition Stardust, which was ultimately settled out of court. However, The Bloom suit concerned renewals on his four most famous instrumental tunes, Spring Fever, Soliloquy, Sapphire and Silhouette. They eventually found in favor of Bloom, and made case law. This allowed for a review of interested parties with legitimate claims to be considered by the copyright office in the Library of Congress for owning the renewal of a copyright either by transfer or by right of having created the work in the first place, rather than the assumed right of renewal by the party currently owning the copyright. This topic would revisited over 40 years later in the so-called Disney/Bono legislation of 1998, which further extended the rights in favor of the original composer instead of their publisher, many cases still in contention concerning the clarity of both the Bloom case (and that of Euday Bowman's 12th Street Rag) and the recent changes in the law.

There was a new surge of interest in Rube's musical style in the late 1960s, and in his late 60s he came back out to perform with Joe Venuti for some reunion concerts in New York. His tunes were further revived in the late 1960s and early 1970s by pianist Dick Wellstood, who recorded some post ragtime novelties in 1973. The only other activity that he was occasionally noted for was trips to the track, as he had taken quite a liking to horse racing, as an observer and bettor. Bloom otherwise largely shied away from the public eye during his last few years.

Rube died at the end of March 1976, just as the second ragtime revival was starting to expand beyond the school of Scott Joplin and Joseph Lamb, and many of the fine early novelty works were finding new popularity among pianists and collectors. According to his obituary in the New York Times, "A maid found him dead on the floor of his room Tuesday [March 30] in the Hotel Consulate in mid-Manhattan. A friend said he had recently complained of an ulcer but it was not known if he had undergone any treatment." He was interred at Beth David Cemetery in Elmont, New York. Three weeks later on April 20, syndicated columnist of the Voice of Broadway, Jack O'Brian had perhaps the last fitting word on Rube's sometimes misunderstood but always important role in American music:

[A New York] paper gave great Tin Pan Alley Rube Bloom a totally unconscious compliment in its obituary: Rube Wrote Cotton Club shows, for a London "Blackbirds of 1936" and deep-south chamber pieces like his "Song of the Bayou." A rewrite-man-in-a-hurry labeled him "the self-taught black composer." Rube was a Yankee Doodle Jewish boy, one of our old friends, a great talent totally revolted by the rock-nonsense. Rube admired black music and soul so much he mastered the Negro mood perfectly. He and Johnny Mercer recently wrote several fine songs - they couldn't even get them recorded!

More than three decades later many of his best pieces are still being performed and recorded, making Mr. Bloom timeless. Not bad for a "self-taught" "Yankee Doodle Jewish boy."

Compositions

Compositions

View More Later Composer Biographies

View More Later Composer Biographies