Bob Zurke represents the all-too-common and tragic story of the hard-living musician who hastens his own demise. In this case in particular he deprived the post-World War II world of a great promise during the revival of traditional jazz and ragtime, although his message was capably conveyed by some of his talented pianist friends. It can also be said that life was hard on Zurke, making it a two way street. For however short it is, his story is worth telling.

Boguslaw Albert Zukowski was born to Polish immigrant parents Felix Zukowski and Felixa "Felicia" Ryehlicka in either Hamtramck Michigan, a Detroit neighborhood, or possibly in Detroit itself. While a January 7 date has been cited, his death records consistently show January 17, which constitutes a higher level of verification. He was the sixth of eight children born to the couple, and between the 1910 and 1920 census many of them had Anglicized their names. They included Watslara "Celia" (1900) and Minnie "Mabel" (1902), both born in Poland, having immigrated with their parents in 1903. Other siblings included Charles "Chester" (1904), Walter (1907), Elvina (1910), Edna (1913) and Virginia (1918). While it might be ascertained that Felix died shortly after the birth of Virginia, an official death record was difficult to locate, and a Felix Zukowski matching the same demographics was found as an inmated in an infirmary near Detroit for the 1920 to 1940 census records. It is possible that he was committed for some reason and Felixa claimed widowed status as a convenience, a common practice at the time. She and her eight children, including Bogust as he is listed, are shown living in Hamtramck in the 1920 enumeration. Felixa was employed as a dressmaker and the oldest two daughters were listed as drill press operators in a local foundry.

Zukowski received training in piano as well as theory and harmony, and perhaps orchestration during his youth. He was a capable arranger and musician, but as a pianist Robert was largely undisciplined, part of what may have enhanced his allure with jazz fans. According to pioneer woman jazz pianist Norma Teagarden, Robert had small hands that could reach little more than an octave, and as a result developed a different kind of style than many ragtime and stride pianists of that time.

Spending most of his first two decades in Detroit during a time when it was a center of jazz and swing band activity, Robert started playing out in his teens, more often in a group than as a soloist. While the reason and exact year are not known, Zukowski acquired the stage name of Bob Zurke by the time he was 16. Among the bands and orchestras he played with included those of smiling Detroit radio star Seymour Simon ("May we come in?"), and the Pennsylvania organization of Oliver Naylor based at both the Orient Nightclub and the Palais D'Or in Philadelphia. His first two known recordings came in September 1928 when he worked briefly with the early swing band headed by a talented female bassist, Thelma Terry and her Playboys. Among the other young performers in her group was drummer Gene Krupa who also made his recording debut with the Playboys. Zurke's career with her would have potentially have lasted longer, but Miss Terry, frustrated by not being taken seriously as a jazz-playing female in a male-dominated field, ended up marrying and quitting professional music shortly after those recording dates. He was also heard in Detroit at Smokey's Club. Bob was clearly on his own by 1930, as his mother was still shown in Detroit living with her two youngest daughters, but he is difficult to locate anywhere in the Federal census.

Around the same time Bob was working with Thelma, he and fellow Detroit musician and future bandleader Glen Gray were hired by leader Jean Goldkette, one of the largest music contractors in the motor city at that time, who had bands throughout the surrounding region and as far off as Toronto, Ontario, Canada. One of his main groups was McKinney's Cotton Pickers which had been started by William McKinney, and was at that time led by Don Redman, who himself had worked for many years with leader/arranger Fletcher Henderson. The young pair of copyists were responsible taking manuscripts by Redman and others and writing out the parts for the individual instruments. This likely involved some decisions which led to subtly arranging pieces as well. To what degree Zurke performed with any of McKinney's groups is uncertain, but Gray moved on from playing in some of his spinoff groups to a career with his own Casa Loma Orchestra within the decade. Redman eventually moved on, forming his own band in 1931 and settling in New York City.

Over the next six years Zurke continued to work in Detroit and surrounding areas, honing his skills as a boogie-woogie and barrelhouse pianist. Among those he traveled and often roomed with was Colorado native Marvin Ash, who would later record some of Zurke's works.

Bob was also married in the early 1930s to Hilda Henderson of Detroit, but a definitive record of this was difficult to locate. The union did result in Robert Albert Zurke, Jr., born on May 20, 1932 in Detroit. In 1937 good fortune came Zurke's way in the form of rising bandleader Bob Crosby. Crosby was a younger brother of by then megastar Harry "Bing" Crosby, and while he had some of Bing's appearance and even a similar voice, he did not have the same range. However, Bing was not a music reader and better suited to singing. Bob, who was headed towards a golfing career, started by singing with the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra, and in 1935 formed his own group out of the remnants of drummer Ben Pollack's band. His first pianist was legendary Chicago player Joe Sullivan, who gave the smaller auxiliary band their name, Bob Crosby's Bob Cats. Gil Rodin also played with the full orchestra, but was less of a soloist except on the "sweet music" pieces. In late 1936, Sullivan contracted tuberculosis and had to drop out of active performing for a while. Zurke, who was able to play in a similar style, was his replacement, joining the group in January 1937.

|

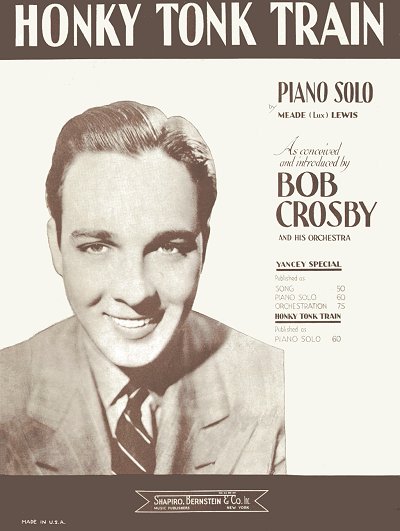

While learning the Crosby catalog he also picked up many of Sullivan's works, some of which had been unpublished, and helped to flesh them out into printed form. Among these were Gin Mill Blues (1933) and Little Rock Getaway (1935), both published as Zurke arrangements by 1939, along with Count Basie's One O'Clock Jump. Gin Mill Blues was also among the first recordings he made with the Bob Cats on February 8, 1937, followed by Little Rock Getaway that summer. Zurke was both a arranger of some note and a piano soloist with the group, which held a unique niche in the beginning of the Swing Era. Utilizing the talents in his band to their best advantage, Crosby spent quite a bit of time resurrecting older traditional jazz numbers in a Dixieland style, and recording well-arranged versions of boogie-woogie pieces as well. Among the most recognizable of those that is still very well known in the 21st century is Honky Tonk Train Blues by Meade "Lux" Lewis, a piece that became a lasting hit for Crosby and Zurke in both published and recorded form. Some of his own compositions also emerged during 1938 and 1939 as a result of his work with Crosby.

Among the most recognizable of those that is still very well known in the 21st century is Honky Tonk Train Blues by Meade "Lux" Lewis, a piece that became a lasting hit for Crosby and Zurke in both published and recorded form. Some of his own compositions also emerged during 1938 and 1939 as a result of his work with Crosby.

Among the most recognizable of those that is still very well known in the 21st century is Honky Tonk Train Blues by Meade "Lux" Lewis, a piece that became a lasting hit for Crosby and Zurke in both published and recorded form. Some of his own compositions also emerged during 1938 and 1939 as a result of his work with Crosby.

Among the most recognizable of those that is still very well known in the 21st century is Honky Tonk Train Blues by Meade "Lux" Lewis, a piece that became a lasting hit for Crosby and Zurke in both published and recorded form. Some of his own compositions also emerged during 1938 and 1939 as a result of his work with Crosby.The first round of recordings Zurke did were with Crosby's larger organization, The Bob Crosby Orchestra. However, during an extended stay in New York City in November, 1937, he participated in a number of sessions both with the orchestra and the smaller ensemble, the Bob Cats. In addition to the orchestra recording some works by the late George Gershwin, the Bob Cats resurrected some older tunes, such as Panama and Squeeze Me, plus some more recent jazz standards. As these sides were released over the next several months the group received praise from within the jazz community for their new dynamic, including from one of the greatest supporters of the music, entpreneur John Hammond. It also helped Bob Crosby achieve his own identity in spite of the considerable shadow of his omnipresent older brother, and gave Zurke new name recognition. Early the following year the group followed up with more old pieces, including a rendition of In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree, At the Jazz Band Ball and Yancey Special, another boogie woogie tune by Lewis dedicated to the genre's pioneer performer, Jimmy Yancey. Zurke gave these tunes great energy and they became popular selling records. Of equal importance is that they brought to the fore of the general record buying population some of the players and composers previously only known within a small segment of the black community of musicians and enthusiasts. Another ambitious group of records was made in Chicago in mid-November 1939, including the famous Honky Tonk Train Blues side, and a pair of tracks recorded by the quartet of Zurke at the piano, Haggart on the bass, drummer Ray Bauduc, and Eddie Miller on the tenor saxophone.

Jazz critics and audiences really began to take notice of the Bob Cats, often singling out the wild pianist of the group. His somewhat undisciplined but dynamic style brought Zurke into the spotlight in 1938, winning a reader's poll for favorite band pianist in Down Beat magazine in 1939. He was also mentioned by veteran player Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton as a favorite contemporary player. As told to historian Alan Lomax on May 23, 1938, "There's only a very few jazz pianists, if there's any, that as I state today. So far as the present time, musicians as pianists, I don't know of but only one that have a tendency to be on the right track, and that's Bob Zurke of Bob Crosby Band. Far as the rest of 'em, all I can see is ragtime pianists in a very fine form."

As told to historian Alan Lomax on May 23, 1938, "There's only a very few jazz pianists, if there's any, that as I state today. So far as the present time, musicians as pianists, I don't know of but only one that have a tendency to be on the right track, and that's Bob Zurke of Bob Crosby Band. Far as the rest of 'em, all I can see is ragtime pianists in a very fine form."

As told to historian Alan Lomax on May 23, 1938, "There's only a very few jazz pianists, if there's any, that as I state today. So far as the present time, musicians as pianists, I don't know of but only one that have a tendency to be on the right track, and that's Bob Zurke of Bob Crosby Band. Far as the rest of 'em, all I can see is ragtime pianists in a very fine form."

As told to historian Alan Lomax on May 23, 1938, "There's only a very few jazz pianists, if there's any, that as I state today. So far as the present time, musicians as pianists, I don't know of but only one that have a tendency to be on the right track, and that's Bob Zurke of Bob Crosby Band. Far as the rest of 'em, all I can see is ragtime pianists in a very fine form."However, Zurke's unruly behavior off the stage also contributed to his eventual undoing. Aggressive horsing around with band bassist Bob Haggart resulted in a broken leg in mid-1937, sidelining him for a few weeks. Zurke played hard and drank hard, and while no definitive mention of drug use shows up in official records, he was involved with many musicians known for frequent marijuana use. His first marriage collapsed sometime in 1938 or 1939, leaving him divorced. By age 26 photographs show that Zurke looked perhaps ten years older than he should have. In March 1939, by which time Sullivan had sufficiently recovered from the tuberculosis, Crosby and Zurke parted ways.

Bob quickly formed his own band, which was funded in part by the William Morris Agency who was promoting his talent. Boogie Woogie piano was enjoying its first national wave of popularity, and Zurke was one of its few white star performers. His group started recording for the Victor Records label as early as July, being touted as Bob Zurke and His Delta Rhythm Band, Bob Zurke and His Orchestra, and Bob Zurke and His Band. The first of these was his official group name, and the latter two likely applied to some of the Victor labels for varying reasons. Zurke likely got the recording contract as a result of his work with Crosby, which had been on the Decca Records label. The recordings were popular mostly for Zurke's style. However, in spite of adequate talent in the front line, and average talent in the rhythm section, the arrangements lacked the luster and polish of the Crosby sessions. Many of the tunes the group performed were copies of those he had done over the past two years with Crosby's group as well. Zurke had brought Sterling Bose with him from the Crosby band, and Bose acted as part time singer on record and a few live performances. Other singers from 1939 to 1940 included Claire Martin, Gus Ehrman and his clear favorite, Evelyn Poe.

The initial buzz on Delta Rhythm was promising. The Chicago Tribune of August 6, 1939, noted that "Bob Zurke, piano playing fugitive from Bob Crosby's band, has launched his own 'Delta Rhythm' orchestra, and is being hailed as a second Zez Confrey." A March 21, 1940, syndicated item stated that "Bob Zurke calls his vocalist, Evelyn Poe, the cat's canary."

Zurke's popularity also got him engaged with mega-group benefits and concerts, including one in early 1940 featuring many of the who's who of big band, Bob Haggart, Gene Krupa, guitarist Charlie Christian, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, and Benny Goodman. One of Bob's signature pieces, Old Tom Cat on the Keys, was recorded in 1939 and published the following year. His most famous work, still played and recorded, was Hobson Street Blues, which was also committed to disc in 1939. Bob was further mentioned in an November 1939 ad for Story and Clark pianos, which stated that he used their pianos at the Paramount Theater in Toledo, Ohio as well as the Paramount Theater in New York City.

|

In spite of how he was regarded by the public, Zurke was not able to hold his life together very well. His band evaporated in June, 1940, after having cut thirty sides for Victor in five sessions over the previous year. The breakup was in part because Zurke was jailed in Detroit for (reports vary) 45 to 60 days for a failure to pay alimony (and possibly child support). After being released in August, Bob went to Chicago where ads show him playing in a few nightspots throughout the rest of the year. He then wandered around the upper Midwest from Detroit to St. Paul/Minneapolis, Minnesota, back to Chicago. At some point in early 1941 Bob was reconciled with his Hilda. After stints in early 1941 in Detroit and St. Paul, Minnesota, they decided to try their luck out west where the center of recording and traditional jazz had shifted, ending up in the greater Los Angeles area late in 1941.

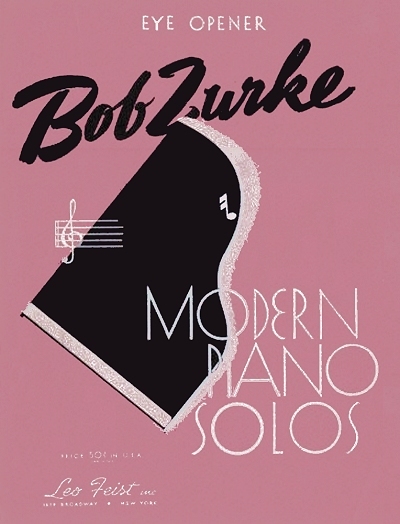

Los Angeles was hard on Bob physically and emotionally, and he in turn was hard on himself. After making his way through various nightspots and trying to hook in with a band (possibly even Crosby's band who was in town to do some recording for Paramount Pictures), Zurke finally secured a spot at the increasingly popular and appropriately named Hangover Club on Vine Street in Hollywood starting in August, 1942. Bob would remain as their resident pianist for the next 18 months. Many of his friends, including Marvin Ash who would later pay tribute to Zurke, had gone off to the war. But others dropped in and jammed with him, including member of the Crosby band. Many of his nights off were filled by Norma Teagarden. Why Bob was not registered with the military is a mystery. There are no records of him under his birth or adopted name in either the draft or enlistment archives for the armed forces. He did branch out with his musical reach, however, and contributed a group of fifteen Boogie Woogie Piano Transcriptions for a 1942 folio published by Robbins Music. Another set of nine Modern Piano Transcriptions was published by Leo Feist in 1944, which included Little Rock Getaway and Gin Mill Blues.

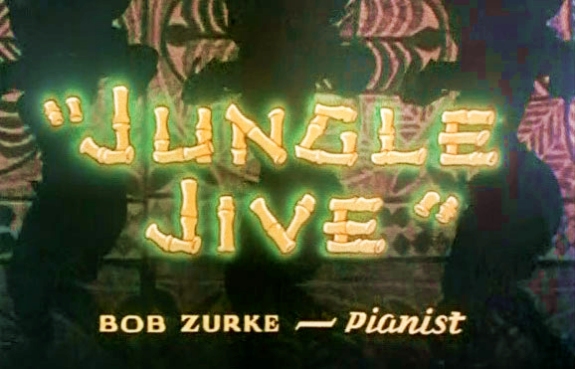

In late December 1943 Zurke recorded a few minutes of hot piano to be used in the upcoming Walter Lantz Swing Symphony titled Jungle Jive and directed by James Culhane. His playing represented a Fats Waller type jungle character playing a piano while tussling with a crab who is trying to play the same piano in a frenetic boogie. Those who have attempted to recreate this performance today have often been injured in the process. It could have been the beginning of a fruitful relationship with cartoons.

Instead, it was his final recording. On the evening of February 15, 1944, Zurke, who was suffering from pneumonia, collapsed while performing at the Hangover Club, and was quickly transported to Los Angeles General Hospital. He had developed a condition similar to the one that had taken the life of Thomas "Fats" Waller a year prior, playing in a hot club near an air conditioner while his body, ravaged from alcohol and hard living, was in a weakened state due to the stress on his liver. Complications from the pneumonia and acute alcoholic poisoning took his life on February 16, just weeks after his 32nd birthday. Bob left behind a widowed Hilda and their two children, Robert Albert, Jr., and Mary Ann (1941). His body was transported back to Detroit for burial at Mount Olivet Cemetery. Hilda and her children moved to Florida where they remained.

|

Clive Acker (of Jump Records) later noted that there were possible other factors that contributed to Zurke's death. He wrote that "Los Angeles is a rotten town for jazz piano men. It destroyed Zurke, it chased out Joe Sullivan, and it made Jess Stacy an 8 to 5 worker." This was in reference to L.A. survivor Ash, who was an avid fan and friend of Bob's, and often performed Hobson Street Blues during his tenure in Los Angeles clubs. One of those included the Hangover Club shortly after his return from the war. Nearly 40 years after Zurke's death, on July 29, 1983, the pianist was honored in his home town of Hamtramck, Michigan, with a memorial jazz band cruise. Among those present was Bob Crosby. Hilda survived until 1988, and Robert Jr. appears to still be alive, residing in Florida. Zurke's music is also still very much alive, performed by a number of contemporary ragtime pianists at various festivals around the world. We will never know "what might have been," but we can certainly be thankful for what was left behind.

Some of the information on Zurke was culled from the Big Bands Database site with help from Bob Zurke's nephew Ray Zukowski. The rest was researched in public records, periodicals and newspapers by the author. Thanks to Caleb Dupree for information on a couple of collaborative compositions.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions