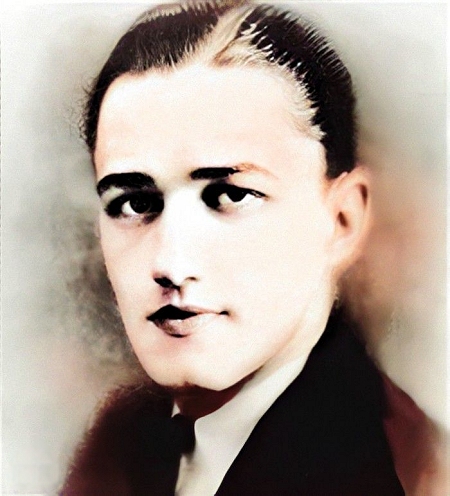

Seger Ellis was a born and bred Texan, the son of bank clerk George Ellis, Jr. and Millien Pillot of Houston. He arrived in the Lone Star State on a hot Fourth of July in 1904. As of the 1910 census the family, including Seger's younger brother Hampton Ellis (1906), was living with Mildred's parents, Nicholas and Pauline Pillot, in Houston. At the time of the 1920 census nothing had changed with the extended family's situation, and George was now listed as an assistant cashier in the bank. Hampton would eventually follow in his father's footsteps, but Seger had a different direction in mind.

Little has been relayed about Seger's musical training, but given his musical capabilities he may have had some light harmony and theory in high school. He also had professional help. He later recalled that there were three piano players in town, Jack Sharpe, Charley Dickson and Peck Kelley. They played at all the parties and made a good living. He would watch them carefully, and finally asked Jack Sharpe for lessons. Sharpe resisted, and tried to thwart the teen by charging five dollars per lesson, a lot of money at that time. But Seger came up with the funds somehow. The lessons consisted of Seger watching Jack play slowly, supplemented by lessons in reading music from another more traditional lady piano teacher.

Seger's musical education also came from The University of Virginia, and he worked his way through school performing in local venues. Ellis was also obviously immersed in popular music forms, and not just those heard in Texas or Virginia. Since his musical upbringing predated radio, his influences likely came from phonograph records and live performances, perhaps even some vaudeville. Just the same, there was some Texas ragtime style present in his blues performances as well, some of it perhaps from Sharpe.

In the early 1920s, with the ragtime era rapidly fading and the decade of novelty piano and the jazz age underway, Ellis entered the field of professional music in Houston. He self-published two of his first songs in 1923 and 1924, and formed his own instrumental group playing popular dance music and some early jazz works and blues.

As radio started to take hold on the American landscape after 1922, station operators first had to establish a stable signal and audience in their respective regions, then look to providing content in order to keep their audience and attract advertisers.

Playing records over the air was not viable in the early days, so the few hours they were on the air every day were filled with live entertainment. In Houston, the station that became KPRC was set up by the Houston Post-Dispatch in a hurry in April 1925 in order to use some equipment they already owned in storage, and to have the exclusive broadcast rights to a speech to be given by commerce secretary (future president) Herbert Hoover. When they signed on for good in May, Seger Ellis as a solo pianist, with his own small group, and with the Lloyd Finlay Orchestra were among the first acts to appear on a semi-regular basis, along with musicians and other artists from around the region. It is probable that Ellis had been on one of the other pioneer Houston stations before 1925, but confirmation of this was difficult to pin down.

|

However, prior to his radio debut, Ellis was "discovered," even though that discovery took a few months. Victor Records, which along with Columbia was one of the predominant record companies in the United States, had been experimenting with electronic recording in early 1925. In order to quickly build up their repertoire and stable of artists to keep their market share and appeal to regional artists, they sent some of their first electronic field units around various parts of the country to find and record new talent. In mid-march they came to Houston where Victor engineers spent a few days auditioning and recording various acts.

Among those were the Lloyd Finlay Orchestra with Seger at the piano, and on March 17th and 18th, 1925, they recorded several sides, four of the takes which were released, two of them Ellis compositions. As Ellis recalled it in a February 1962 Jazz Journal International article, "The Victor A&R man came to town to record Lloyd Finlay's pit band at the Majestic Theater. He wanted to do eight sides, but Finlay was only ready with four numbers and the A&R man, that was Eddied King, had only two with him. Then they heard me playing on the radio... and he came around and asked me for two original numbers."

The Victor managers in New York were impressed enough with what their engineers returned with that they asked Seger, now a rising star in his native Houston, to come to Camden, New Jersey to record more sides for the label. The performances he laid down were fine, but there were technical issues with the recordings themselves. He ventured back there over the summer, and on August 10th through 12th recorded as many as 45 to 50 takes of several of his own compositions, and a couple of others that he knew. However, the difficulties of early electronic recording and lack of experience on what microphones to use for piano solos and how to use them got in the way, and in the end only three of those sides, Prairie Blues and Sentimental Blues, were deemed usable. Several other takes were put on hold or destroyed. Still, he was among the first Victor artists, perhaps the first pianist to record commercial solo jazz and blues piano sides electronically to disc during the nationwide crossover to this technology between 1925 and 1927.

These first two released tracks do tell us a bit about the evolving style of the 21-year-old pianist. Prairie Blues is a laid back piece with elements of a strong barrelhouse left hand - more of a left hand vamp that is chord based rather than the traditional ragtime bass.

Each chorus is unique and original, and some phrases of the performance could be characterized as boogie-woogie. Sentimental Blues has both a verse and chorus, and is an eighteen bar blues. His performance plays with both major and minor modes, with a prominent and consistent rolling left hand. Ellis himself noted that "I had a weird left hand. It puzzled everybody... They were all playing one note and a chord then, like Fats Waller... My stuff, it was gutbucket but I deviated slightly from the standard blues changes, put in a few extra chords."

|

His style was indicative of the early East Texas barrelhouse style as performed by other blues and boogie-woogie figures such as Will Ezell and George and Hersal Thomas. This enhances the chance that Seger actually heard, and possibly knew these other players as they roamed throughout the south in the early 1920s. His Ash Can Blues, one of the original Victors that survives in spite of not being issued, is further proof of this, as it has been compared to 31 Blues played by Bob Call, another fine Texas blues pianist. It was backed by one of his first songs, You'll Want Me Back Some Day, recorded in early 1926.

In spite of his potential as a dynamic boogie pianist bordering on stride piano, a different path would eventually be chosen for Seger by public acclaim. It started during his radio days or performing in the vaudeville houses in Houston and surrounding areas. Ellis had a relatively high but smooth tenor voice, yet he was reportedly uncomfortable with the prospect of his singing. Given that radio was such an important medium for audio, and that during that period most radio sets had better sound potential than the average acoustic phonograph player, it was a given that his employers at KPRC would want Seger to go with the growing trend of bands with singers. They felt that it was difficult to sustain 90 minutes of piano solos at that time, so they asked him to vocalize. Seger felt his voice was too high to be accepted by the public, but their reaction was quite the opposite, and it was his vocalizing that made him more of a star than his dynamic piano playing did.

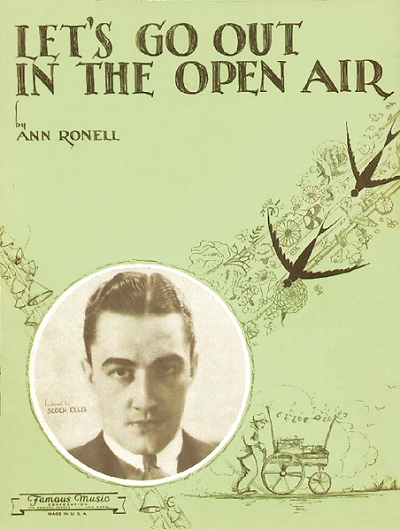

Ellis was again invited back east, this time by Columbia Records, and in November 1926 his career as a handsome and charismatic tenor on the national stage began with the piano and vocal recording of Sunday. Over the next 20 months he would lay down several vocal tracks for Columbia, and these in turn put his picture on a number of sheet music covers, a silent promotion that still worked well for artists and composers in the 1920s and 1930s. Almost simutaneously Ellis began an even longer career playing for Okeh Records after Columbia purchased them. Seger moved to New York around this time.

He recorded both on his own as a pianist/vocalist, with pickup groups of his own choosing labeled as the Seger Ellis and His Orchestra, and with a variety of other artists. Among these were Russell Douglas, The New York Syncopators, the Justin Ring Trio, The Royal Music Makers and The Tampa Blue Trio. He became prominent enough that he warranted his own picture label, something reserved only for the real Okeh stars including Paul Whiteman and Ted Lewis. Between 1926 and 1929 he was the third best selling record artist in the United States.

|

One pair of recordings in particular put him in with the top musicians of that period. On June 4, 1929, Ellis provided vocals for S'Posin' and To Be In Love, joined by no less than Louis Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey and drummer Stan King, along with his orchestra leader pal Justin Ring on piano. This was rare in that Louis had rarely worked outside of his own band during this period. That the black Armstrong's first track as an independent was on a date for the white Seger Ellis is of some historical significance. It is also probable that Armstrong played trumpet against Seger's vocal on the recently penned Ain't Misbehavin' in August, 1929. Ellis further wrote arrangements for Armstrong, cornetist Muggsy Spanier, trumpeter Manny Klein, the legendary but troubled Bix Beiderbecke, guitarist Eddie Lang and jazz violinist Joe Venuti, all Okeh artists in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

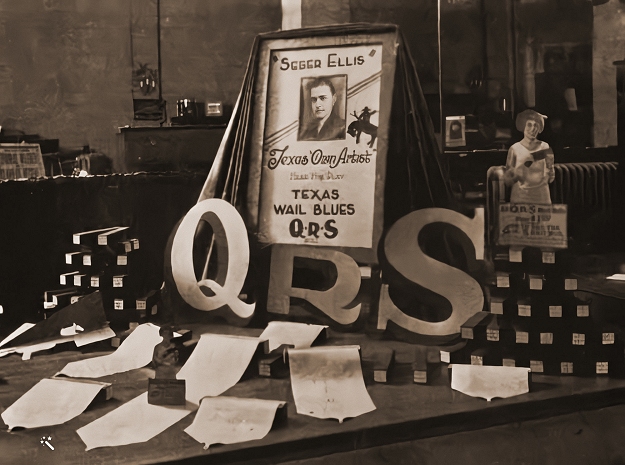

Early in 1927 Ellis was invited to the U.S. Music studio to record one of his characteristic pieces. The end result was Texas Wail Blues, also released with minor changes on the QRS label, and which was heavily promoted in Texas. In March 1927 he was back in the Houston area performing it on stage and at music stores both in Houston and San Antonio, later in the Dallas Fort Worth area.

It is also a moderate tempo blues in which his left hand style challenges the player mechanism to keep up with his dynamic pseudo-stride pulse. In early 1928 Seger was taken in by the Robbins publishing firm. According to the Music Trade Review of March 3, 1928: "A contract with the Robbins Music Corp., New York, was signed this week by Seger Ellis, popular recording pianist, who is preparing a series of piano solos for publication by this house. Mr. Ellis, a native of Houston, Tex., started working out his own ideas in piano playing and drifted to the jazz and blues style."

|

In all, Seger appeared on at least 95 Okeh sides between November 1926 and December 1930, followed by a small quantity of just ten Brunswick recordings through June 1931, primarily as a vocalist, but on rare occasions as a pianist. Four Okeh instrumental sides in particular stand out, as does another interesting vocal. In March 1930 Seger recut his first two blues, Prairie Blues and Sentimental Blues, for Okeh. There is only a slight evolution noticeable in this higher fidelity tracks, but they remain fairly true to his Victor takes. Then he took on the by now ubiquitous St. Louis Blues to great effect. But the A side of that record was his Shivery Stomp, a romp that is a standout among the Seger Ellis piano tracks and his admitted favorite as well. While not overly inventive harmonically, it is a showcase for his heavily chorded left hand barrelhouse style, which includes a couple of cleanly executed scales rising up to the right hand melody. Rhythmically it pulses throughout, but with such a fascinating effect that it borders between music that encourages dance movement and that which encourages concentrated listening. Shivery Stomp was also covered by Bix Beiderbecke, and by Frankie Trumbauer and His Orchestra ten months before Ellis' own, recording, also on the Okeh label. This time line indicates that Trumbauer may have had an ongoing musical relationship with the pianist (Seger had added vocal to one Trumbauer side), and also that it and other pieces obviously predated their composer's recording dates by quite a bit.

One more interesting track was a vocal with orchestra and piano backing. St. James Infirmary, a venerable New Orleans lament. It was recorded on January 21, 1930. It has elements of boogie bass as well as the persistent funerial pulse throughout.

It also includes a rarely-heard verse that would be controversial even today: "I want sixteen roll-the-dice shooters for my pall bearers; want nineteen women [to] sing my funeral song; sprinkle mari-juana in my coffin, and let those [muter?] hands forget all as they go slowly 'long." It is hard to find this verse elsewhere, and authenticity as to a New Orleans origin is also difficult to establish. But this inclusion does show some early connection between jazz musicians and marijuana, which became more prominent in the coming decades, particularly with a future friend of Ellis, drummer Gene Krupa. As for Ellis himself, the author found no reports of known reefer use.

|

While many artists often performed or composed using a pseudonym, Ellis was not known to do this except on an occasion where it was called for. In this case it was Okeh who had a floating band name backing one of their novelty minstrel and country yodeling vocalists, Emmett Miller. On at least a couple of sides, Seger filled in as Bud Blue, a.k.a. Buddy Blue, Buddy Blue and his Texans, and various other contrivances. Other Okeh artists of that period also stepped into the Bud Blue shoes, usually pianist Fred Rich. The group also backed singer Smith Ballew although it appears Ellis had no part in his sessions. Being from Texas, Seger probably took these requests in stride.

Ellis had toured England in 1928 as a soloist, and was once again out of the country for the 1930 census, so some points of his life at that time are hard to confirm. He was married at that time to Vivian Masterson from Angleton, Texas. They arrived in England from New York on April 3, 1930, and returned on May 28 from Cherbourg, France. Whether this was for a music tour or simply a trip (honeymoon?) with his wife is not clear. However, other known band members were not found on either of the ship rosters. It also indicates that the couple was living at that time at 8267 Austria Street in Kew Gardens, a neighborhood in Queens, New York.

And then it seemed to just end. It is unclear whether Ellis fell out of favor with the public, or with Okeh Records, or just wanted to lay back for a while. His last tracks for a while were recorded in June 1931. The Great Depression was taking hold of the country and the globe, and record sales dropped as much as 85% between 1929 and 1931, given that a radio was cheaper to maintain and was always current. While there has been a lot of speculation on what Ellis was up to during this period, some scant listings have been found for him as a vocalist, mostly in the Houston area. However, he also worked as a booking agent for talent for several years in the mid-1930s.  An article in the Pittsburgh Press of March 28, 1934, confirms that Ellis was living or staying in Cincinnati, Ohio at that time, and had previously won first place in one of their national radio talent contests. There are also mentions of him performing on WLW in Cincinnati where he made a discovery of his own. One of the groups he heard there, and then promoted to fame were The Mills Brothers, who went on to a fairly lucrative career in the 1940s and 1950s, initially under the management of Seger. Ellis contributed songs to their catalog for nearly two decades. He also was partly responsible for the rise of Sammy Cahn (Cohen), who had a stellar career as a songwriter and musician, and his early partner Saul Chaplin. There is otherwise very little mention of Ellis between mid-1931 and mid-1936.

An article in the Pittsburgh Press of March 28, 1934, confirms that Ellis was living or staying in Cincinnati, Ohio at that time, and had previously won first place in one of their national radio talent contests. There are also mentions of him performing on WLW in Cincinnati where he made a discovery of his own. One of the groups he heard there, and then promoted to fame were The Mills Brothers, who went on to a fairly lucrative career in the 1940s and 1950s, initially under the management of Seger. Ellis contributed songs to their catalog for nearly two decades. He also was partly responsible for the rise of Sammy Cahn (Cohen), who had a stellar career as a songwriter and musician, and his early partner Saul Chaplin. There is otherwise very little mention of Ellis between mid-1931 and mid-1936.

An article in the Pittsburgh Press of March 28, 1934, confirms that Ellis was living or staying in Cincinnati, Ohio at that time, and had previously won first place in one of their national radio talent contests. There are also mentions of him performing on WLW in Cincinnati where he made a discovery of his own. One of the groups he heard there, and then promoted to fame were The Mills Brothers, who went on to a fairly lucrative career in the 1940s and 1950s, initially under the management of Seger. Ellis contributed songs to their catalog for nearly two decades. He also was partly responsible for the rise of Sammy Cahn (Cohen), who had a stellar career as a songwriter and musician, and his early partner Saul Chaplin. There is otherwise very little mention of Ellis between mid-1931 and mid-1936.

An article in the Pittsburgh Press of March 28, 1934, confirms that Ellis was living or staying in Cincinnati, Ohio at that time, and had previously won first place in one of their national radio talent contests. There are also mentions of him performing on WLW in Cincinnati where he made a discovery of his own. One of the groups he heard there, and then promoted to fame were The Mills Brothers, who went on to a fairly lucrative career in the 1940s and 1950s, initially under the management of Seger. Ellis contributed songs to their catalog for nearly two decades. He also was partly responsible for the rise of Sammy Cahn (Cohen), who had a stellar career as a songwriter and musician, and his early partner Saul Chaplin. There is otherwise very little mention of Ellis between mid-1931 and mid-1936.But he was still to be seen, as well as heard, during this period. His picture still surfaced infrequently on sheet music covers throughout the 1930s. Seger's voice had also been heard in a couple of early sound films for Warner Brothers. Then things started to pick up a bit. In addition to his booking agent duties, there was a short-term gig as a vocalist in the mid-1930s at station KFPG/KMTR (now KLAC) in Los Angeles, California (KMTR is now in Eugene, Oregon). Other indicators show that he stayed in Los Angeles from 1935 to at least 1937, also appearing frequently on KHJ with his orchestra, and performing with Paul Whiteman's orchestra. He also appeared on screen in 1936 in One Rainy Afternoon, singing Secret Rendevous with Margaret Warner.

In 1935 Ellis started to form a big band, his Choir of Brass. The original consist of the group was four trumpets, four trombones, a clarinet, drums, bass and two pianos. Seger spent more than a year picking personnel and developing unique jazz arrangements for the group with the help of Spud Murphy who had also worked with Benny Goodman's arranger Fletcher Henderson. Out of some 80 arrangements they cut several sides in 1937 which were later released on a long-playing record. This group performed and recorded until 1941, but Ellis' role was mostly as the leader and arranger, as he rarely played piano with them. The Choir of Brass was ahead of its time, and perhaps too early to trend, given their advanced approach to jazz and swing, so the group did not fare well overall. One of their more complex tracks was a brass arrangement of Shivery Stomp.

During this period Seger started appearing both as a soloist and with his groups at venues in the larger cities, including Los Angeles and New York.

He cut several sides with a more traditional instrumental makeup for the up and coming Decca label in 1937, billed as an orchestra once again (which may have been the Choir of Brass in disguise at times), and was back in business with Brunswick Records the following year into 1939 as Seger Ellis and His "Choir of Brass" on some cuts, and the orchestra on others. On the choir, Seger later told the Jazz Journal International, "The things that band did... if we'd have done them four years later we'd have made a hell of a lot of money. But the public wasn't ready for it then. Goodman was just breaking the ice with something that he was swinging and loud and he hadn't broken enough to let everybody in."

|

By 1939 Ellis and his orchestra were steadily engaged in the east and got plenty of exposure on national radio broadcasts, mostly with him singing and rarely featured on the piano. Another singer featured with him, starting as early as mid-1938, was his (presumably) second wife, Irene Taylor. (Attempts to find dates of his first divorce and second marriage came up empty.) By 1940 the Brunswick and Vocalion company, which had also issued some Ellis records in 1940, was purchased and consolidated along with most of their contracts. So Seger briefly went back to work once again for a reorganized Okeh label under CBS, largely covering swing music arrangements.

As of the 1940 census, taken in at the Hotel Belvedere on West 48th Street in Manhattan, Seger and Irene were listed respectively as an orchestra leader in a night club and a singer in (likely the same) night club. Working in this capacity and with CBS through the summer of 1942, Ellis enlisted in the Army Air Corps in September. His role in the military is unclear, but there are no mentions of him in the Stars and Stripes magazine of the war years, so it may have been more as a soldier than as an entertainer. His stay there was short-lived, and followed by a "defense job." Ellis' marriage to Taylor ended around this time, as did two subsequent marriages over the next few years.

It is hard to find much of mention of Seger in the press after 1942, except for when his compositions were performed by other artists. There was a short-term arrangement with the Harry James Orchestra in the period after Frank Sinatra left, but Ellis was not a crooner, so no recordings came out of it. Seger ran a bar in the Houston area from the late 1940s through perhaps the 1950s. He struck a bit of songwriting gold in 1948 with You're All I Want for Christmas, which was quickly covered by the ultimate Christmas songster of the time, Bing Crosby. Recordings by Frankie Laine and Al Martino help to make it an instant classic. The 1950 census showed Seger residing in Houston at his widowed mother's home, and curiously with no occupation listed.

|

In the late 1940s and early 1950s Ellis cut some sides for the Bullet label in Nashville, as well as two sides for MGM records. A few tracks also appeared on the independent Kapp label in the 1950s. During this period Seger wrote a few tunes for Gene Krupa, who had gained fame with Benny Goodman's band and was now recording and touring with his own group. Seger also married a fifth time to Pamela Ellis who remained with him through his death. There is a copyrighted score for a musical called The Oilers about the Houston football team that was registered in 1960, but it was evidently never sold or staged. His pirmary income came from nightclub appearances and some fair-sized checks from ASCAP, of which he was a member.

As of late 1961, when he was interviewed by John Bryan of the Jazz Journal International published in London, England, Ellis had settled into a "comfortable brick house directly behind the storied Shamrock Hilton Hotel in Houston." He was still writing the occasional song, and even produced one for the article, I Wish I Had My Old-Time Sweetheart Back Again. In his laments about the old days Ellis noted the tragedy of the talented Bob Zurke, who he feels never got his proper due with the Bob Crosby band. On the current state of jazz, he stated that "Most guys today don't play much left hand. They play both together, block hands. Today when a guy cuts a piano solo he makes it with bass, a drummer, maybe a guitar. In the old days we worked alone on the solos and we had to carry it ourselves." Given the number of cuts Seger made with ensembles as opposed to solos, this seems contradictory, but there were a few other variances in his memory as well that found their way into the story.

After 1962 the trail goes mostly cold for a while. Local Houston PBS station KUHT produced an hour-long documentary about the composer in the 1970s. Both a mention of Ellis and a 1989 picture are found on the BlueTone Piano Roll site on the Memorials page. Ellis was interviewed on June 15, 1991 by Clay Shorkey and Rudy Martinez, a recording which is preserved at the Texas Music Museum. He finally passed away in September 1995 in his native Houston at age 91, and was buried at the Everglade Meadow in the Hollywood Cemetery in Houston as an Army veteran.

Historically there were many who were and are fans of Seger's singing voice, and many who are also detractors that regard his vocals as "nightmarish" at the very least. Most late 1920s and 1930s collectors have all but forgotten about his dynamic and driving piano style. However, there are still recordings of his solos available in the digital domain that remain as a reminder of how this Texas boy got his start so long ago.

Thanks to historian Dave Lewis for inciting this article, and Nick Artega who contributed a little bit of information on Ellis' early recordings.

Compositions

Compositions