Almost any collector of ragtime music has come across at least one or more pieces of music by S.R. Henry, two of them in particular. During the ragtime era of the 1900s and 1910s, the real identity of the composer of By Heck and S.R. Henry's Barn Dance was a poorly kept secret in Manhattan and beyond, given the association with his famous brother and his brother's partner. However, that knowledge somehow faded from the mid-1920s forward. So, a century later, the identity of the person behind the famous pseudonym can perhaps be a surprise once again.

He was born Henry Robert Stern in the heart of Manhattan, New York, to German immigrant parents Charles Stern and Theresa Katz. Henry had two older siblings, including his sister Hattie (5/11/1872), and brother Joseph W. (1/11/1870). Charles was a necktie manufacturer, and during their youth each of the boys participated in some way in the family business. However, they were also both musically inclined to a degree, and sought some education in piano, harmony and theory. Henry took his music education to a bit of a higher level than the New York City School System, studying music at the City College of New York, and then Columbia University, where he received a Ph.D. in his early twenties. By that time, his brother Joseph was already becoming involved in the music business.

Edward B. Marks was an aspiring lyricist who was gainfully employed as a traveling salesman of garment accessories like hooks and eyes. Joseph, who was helping his father sell neckties in the mid-1890s, met the somewhat older Marks through their garment industry association. Although he was a rank amateur compared to Henry, Joseph wrote a maudlin tearjerker ballad with Marks titled The Lost Child. They even concocted a lantern slide show to go with performances of the piece, helping to usher in the age of "Illustrated Songs," which would be popular in the 1900s and 1910s. Seeing some potential success on the horizon, the duo followed this up with Mother Was a Lady, and decided to form their own firm to market their music, and perhaps publish similar works by others. As this was a venture with some risk, Marks did not want to alert his employer that he was moonlighting in a risky endeavor, so they named the firm Joseph W. Stern & Company, founded in 1894.

As this was a venture with some risk, Marks did not want to alert his employer that he was moonlighting in a risky endeavor, so they named the firm Joseph W. Stern & Company, founded in 1894.

As this was a venture with some risk, Marks did not want to alert his employer that he was moonlighting in a risky endeavor, so they named the firm Joseph W. Stern & Company, founded in 1894.

As this was a venture with some risk, Marks did not want to alert his employer that he was moonlighting in a risky endeavor, so they named the firm Joseph W. Stern & Company, founded in 1894.Among the first clients they took on, and continued to support over the next two decades, were those who had the hardest time getting published — namely the African-American songwriters of New York and beyond. Marks also pursued classical composers, becoming an agent for American publication of European works, including operettas, musical comedies and art songs. With the onset of cakewalks and ragtime, and a marked increase in competition starting around 1897, there was no shortage of popular material either, ranging from "coon songs" and "pathetic ballads" to vivacious piano ragtime. Given the breadth of their output, it was not long before the Stern firm found themselves moving from their initial location on 14th Street in lower Manhattan to 28th Street, which in the early 20th century would acquire the name "Tin Pan Alley." The expansion also required a bigger staff, and one of those hired on in a multi-function role was Henry R. Stern.

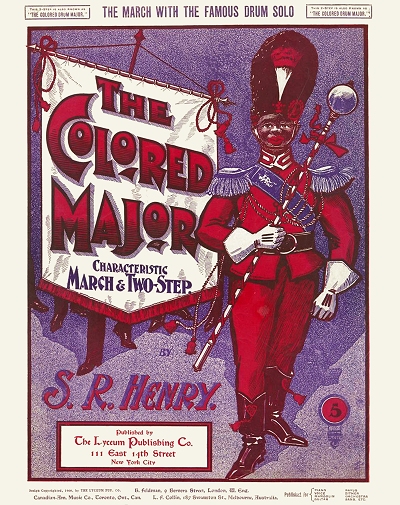

It may have been an attempt to avoid the appearance of nepotism, or simply to divide administrative duties with the firm from his musical inclination, but Henry decided very early on that he would use the pseudonym S.R. Henry, a variation of his given name, for his published output. To that end, there are copyrights under that name from 1899 into 1941. The 1900 enumeration taken in Manhattan showed Henry residing with Hattie, her husband Simon B. Minder, their child Bendix, and Henry's parents. The elder Stern was still making and selling neckties, but Henry was listed as a music publisher. He had a relatively solid hit that year in The Colored Major, which fell just short of ragtime with its cakewalk figures, but was cast in the guise of "coon music" popular at that time. It would be followed by the minor hit, The Colored Ragamuffins, in 1903. Given that his compositional output was relatively light, he may have been hedging his bets on a full-time career in music. The city directory for 1903 suggests that Henry was not entirely out of his father's business, as he was listed under neckwear supplies.

The city directory for 1903 suggests that Henry was not entirely out of his father's business, as he was listed under neckwear supplies.

The city directory for 1903 suggests that Henry was not entirely out of his father's business, as he was listed under neckwear supplies.

The city directory for 1903 suggests that Henry was not entirely out of his father's business, as he was listed under neckwear supplies.On January 20, 1904, Henry was married to Cora Rose, whom he would remain with for life. She would give birth to their first son Cyril on November 11, 1904, and then to Henry Robert, Jr. on October 29, 1909. During that period Henry's stock would rise dramatically with his brother's company and the music business in general. By the time of the 1905 New York census, there were two servants in the household at 325 Central Park West at 92nd Street. In 1906, Henry teamed with aspiring lyricist James J. Walker for a song, and arranged a couple more for him, all issued by Joseph Stern. Walker would become one of New York City's more colorful mayors in 1926. According to a Music Trade Review notice in 1907, Henry was working as a manager for the Landay Brothers firm, a piano dealer and music print jobber, in addition to his duties with the Stern organization.

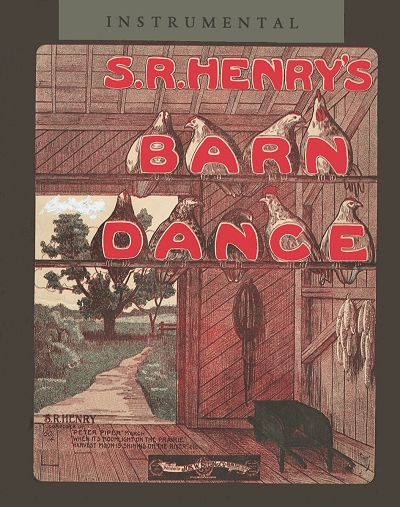

Picking up composition momentum ever so slightly, Stern hit on something in 1908 when he issued the catchy rural swing tune S.R. Henry's Barn Dance. Scored with dotted rhythms throughout, it picked up on the coming trend away from straight 16ths, paving the way for the swing that would be a part of jazz in the late 1910s. Judging by extant copies found in antique malls around the United States, this piece sold relatively well in its time. It was also incessantly promoted in the music and entertainment trades. Another similar barn dance tune would make an appearance in 1910, but it did not resonate as well with the public. There were also several songs written during this period, some with fine lyricists on the Stern staff or at least contracting with it, including Arthur J. Lamb, Monroe H. Rosenfeld, James O'Dea and Alfred Bryan. Most of them were average at best, and have not survived the century that followed with any staying power. The 1910 census showed the Sterns residing in Manhattan on Madison Avenue on the East side of the park with their two children and three servants. Henry was listed as in the music business with his own shop, possibly a reference to the piano and printing business he managed.

In terms of Henry's duties at his brother's firm, which was now closer to Broadway up on 38th Street, they required a great deal of intuition and discernment when it came to his ability to scout out good publishable material and present it to artists or the public in general. It appears that he worked a lot with foreign composers and publishers, and less with the popular music side of the business, as may be discerned from this commentary in Variety of December 23, 1911, discussing various aspects and policies of publishing firms:

Ragtime Vs. Comical

To anyone conversant with the output of the various music publishers, it must be apparent that we have been for the past few years favoring better-class compositions and operatic productions, in preference to the lighter forms of American ballads and ragtime numbers, our reason for this being that we have found the American public is becoming more and more discriminating and educated in music, demanding better material all the time.

The increased patronage of grand opera and the high-class foreign musical productions, bear witness to this fact. Moreover, the returns from the sales of a popular song success are not commensurate with the enormous amount of plugging and expenditure required to land a hit, a popular hit being an ephemeral proposition, lasting nowadays about six months at the most; and when you couple this fact with the ridiculous price of 6c. to 7c. at which this class of music must be sold to the trade, the point of our argument becomes apparent.

The public has evidenced a decided preference for musical shows written by eminent composers (mainly foreign), whose scores contain real music of lasting qualities.

The regard that Joseph and Edward had for Henry was tacitly expressed in an extensive Billboard article, Song World's Encyclopedia, highlighting publishing firms around the United States, in the December 5, 1912 edition:

Stern, Jos. W.—Combined genius of Edward Marks' business ability and Joseph W. Stern's knowledge of the music publishing game. These two famous huntsmen have built up one of the most successful music-publishing concerns in the world, their specialty being to hunt in foreign grounds for rare game in the form of production music, the rights of which are valuable after the show is transferred to the American stage. Henry Stern handles a great portion of the "active policy" of the firm and much of its success is due to his efforts.

Having been involved in so much theatrical music, both European and American, it was likely unexpected when Stern started getting more involved with vaudeville artists and the creation of acts for the stage. In that regard, Billboard referred to him as "the smiling deacon of constant endeavor." How much he contributed is uncertain, and it may have been under another pen name to distinguish himself from his composition output. However, he probably wrote or fine-tuned music and some libretto for various acts, and then worked to get them placed in New York theaters or traveling companies. Also, in his role as a publisher liaison with artists and management, in 1914 he became a charter member of the Music Publisher and Dealer's Association. He was present when their constitution, largely penned by Marks, was adopted and signed on February 27, 1915. In fact, when Billboard editor Walt Hill - an outsider to the organization in some regards - was called up as one of the many speakers that evening, he started his awkward oration with the introduction, "Mr. President, gentlemen of the music trade, fellow space-stealers and Henry Stern…"

In that regard, Billboard referred to him as "the smiling deacon of constant endeavor." How much he contributed is uncertain, and it may have been under another pen name to distinguish himself from his composition output. However, he probably wrote or fine-tuned music and some libretto for various acts, and then worked to get them placed in New York theaters or traveling companies. Also, in his role as a publisher liaison with artists and management, in 1914 he became a charter member of the Music Publisher and Dealer's Association. He was present when their constitution, largely penned by Marks, was adopted and signed on February 27, 1915. In fact, when Billboard editor Walt Hill - an outsider to the organization in some regards - was called up as one of the many speakers that evening, he started his awkward oration with the introduction, "Mr. President, gentlemen of the music trade, fellow space-stealers and Henry Stern…"

In that regard, Billboard referred to him as "the smiling deacon of constant endeavor." How much he contributed is uncertain, and it may have been under another pen name to distinguish himself from his composition output. However, he probably wrote or fine-tuned music and some libretto for various acts, and then worked to get them placed in New York theaters or traveling companies. Also, in his role as a publisher liaison with artists and management, in 1914 he became a charter member of the Music Publisher and Dealer's Association. He was present when their constitution, largely penned by Marks, was adopted and signed on February 27, 1915. In fact, when Billboard editor Walt Hill - an outsider to the organization in some regards - was called up as one of the many speakers that evening, he started his awkward oration with the introduction, "Mr. President, gentlemen of the music trade, fellow space-stealers and Henry Stern…"

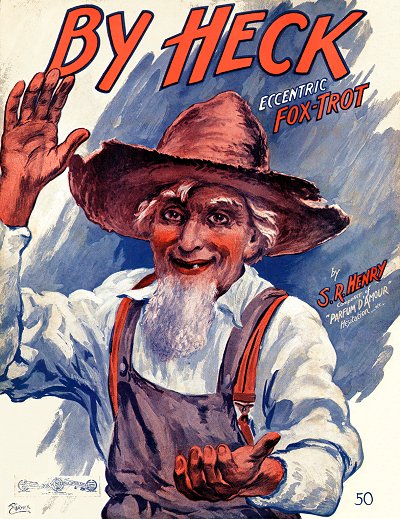

In that regard, Billboard referred to him as "the smiling deacon of constant endeavor." How much he contributed is uncertain, and it may have been under another pen name to distinguish himself from his composition output. However, he probably wrote or fine-tuned music and some libretto for various acts, and then worked to get them placed in New York theaters or traveling companies. Also, in his role as a publisher liaison with artists and management, in 1914 he became a charter member of the Music Publisher and Dealer's Association. He was present when their constitution, largely penned by Marks, was adopted and signed on February 27, 1915. In fact, when Billboard editor Walt Hill - an outsider to the organization in some regards - was called up as one of the many speakers that evening, he started his awkward oration with the introduction, "Mr. President, gentlemen of the music trade, fellow space-stealers and Henry Stern…"In 1914 Henry produced yet another barn dance type of piece, the somewhat raggy fox trot By Heck. There is some possibility that the delightful Starmer Brothers cover of a clapping rube helped sales along, and many of them are still seen more than a century later. It was successful enough that it received international distribution, and a song version was issued in 1915 with lyrics by no less than L. Wolfe Gilbert. The 1915 New York census indicated that the family had moved again, this time to the upper west side on West End Avenue.

Delving more into matters theatrical, Henry, Edward and Joseph formed the International Theatrical Play Bureau during the early-to-mid-1910s as a branch of Stern Music, with Henry and J.K. Adams as liaisons and artist representatives. They helped to place a lot of domestic and foreign properties into venues, and fill them with reliable writers, directors, actors, musicians and music. These early investments in the field paid off in particular for Stern after World War I, as by that time their only major competition from E. Rachman of Famous Players Lasky was less than formidable. Henry also helped to negotiate a reduction in royalty demands from foreign attractions, especially when exchange rates changed after the war, giving European properties greater chances for exposure in the United States. At any time just before and then after the United States' involvement in the European war, Henry and the Play Bureau had contracts on forty or more viable foreign properties.

At any time just before and then after the United States' involvement in the European war, Henry and the Play Bureau had contracts on forty or more viable foreign properties.

At any time just before and then after the United States' involvement in the European war, Henry and the Play Bureau had contracts on forty or more viable foreign properties.

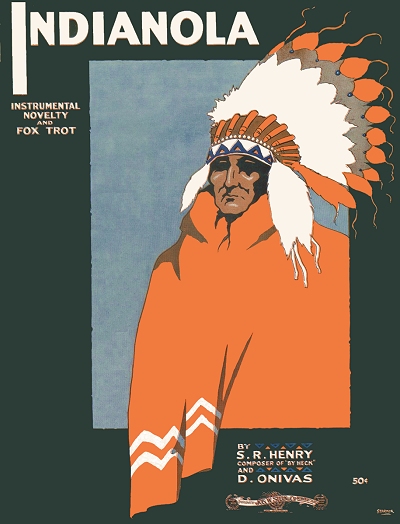

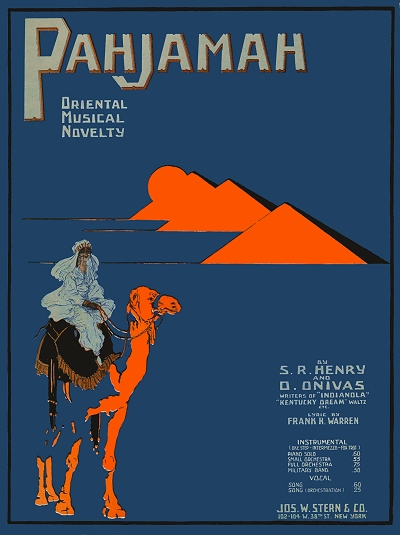

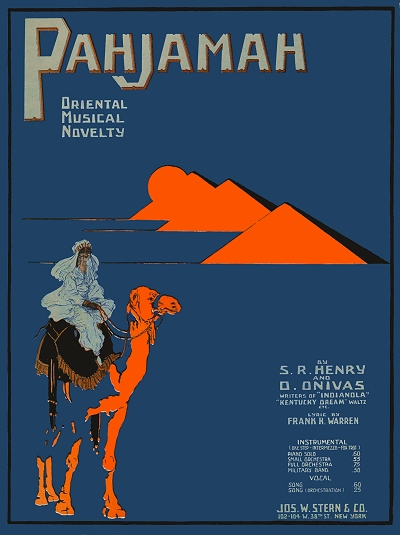

At any time just before and then after the United States' involvement in the European war, Henry and the Play Bureau had contracts on forty or more viable foreign properties.While Henry's output of compositions had taken a hit due to all of his other responsibilities, he still managed to turn out something noteworthy now and then. In 1917 that was the novelty fox trot Indianola, a supposedly American Indian-themed work about a decade after the trend had peaked. However, it made for a good fox trot with a few hesitations and other neat musical tricks, so Indianola, recorded by several groups, became yet another hit for Stern. As may be expected, a song version was issued the following year. For his September 12, 1918, last call draft record, Henry still claimed his primary vocation to be music publisher. In 1919 he scored with another minor hit, Pahjamah: Oriental Novelty, at a time when Dardanella and others of that ilk were being passed out left and right. Although it had about the same level of ethnic authenticity as Indianola, and make no mistake that many of these stereotypical pieces were applied to scenes with matching ethnicities by silent film pianists around the United States, Pajamah still remains popular a century later, having long been used by certain circus music directors, including the famous Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus, for Asian specialty acts or clown hijinks. A song version of piece was available later in the year.

Having been closely involved with theatrical productions for so long, it was natural that the composer side of Henry Stern would want to be directly involved in a show. So, in 1920, along with Domenico Savino and Edward Clarke, he wrote and helped to produce the musical Little Miss Charity, based on Clarke's comic play Not With My Money. It debuted in September of 1920, but not without a little controversy. Theater director R. C. Herndon, in conjunction with Stern and Savino, not only decided to change the story around, but asked Clarke to not attend the rehearsals, and did not consult him concerning casting or the changes. He was visibly absent when the musical opened on September 2 at the Belmont Theater, and actually asked papers running the advertisements to remove his name as he did not want to take any credit for the work, making Savino and Henry the culprits if it failed. It did not fail, and did fair business both in New York and on the road. In spite of that success, it would be Henry's swan song.

He was visibly absent when the musical opened on September 2 at the Belmont Theater, and actually asked papers running the advertisements to remove his name as he did not want to take any credit for the work, making Savino and Henry the culprits if it failed. It did not fail, and did fair business both in New York and on the road. In spite of that success, it would be Henry's swan song.

He was visibly absent when the musical opened on September 2 at the Belmont Theater, and actually asked papers running the advertisements to remove his name as he did not want to take any credit for the work, making Savino and Henry the culprits if it failed. It did not fail, and did fair business both in New York and on the road. In spite of that success, it would be Henry's swan song.

He was visibly absent when the musical opened on September 2 at the Belmont Theater, and actually asked papers running the advertisements to remove his name as he did not want to take any credit for the work, making Savino and Henry the culprits if it failed. It did not fail, and did fair business both in New York and on the road. In spite of that success, it would be Henry's swan song.The Christmas day, 1920, issue of the Music Trade Review made the dramatic announcement: "E.B. Marks Now Sole Owner of Jos. W. Stern & Co." After nearly 27 years in business together, Joseph Stern decided to retire and sold his interest in both the publishing arm and the theatrical bureau to his long-time silent partner and his brothers. Both Joseph and Henry went into retirement as relatively wealthy men for their nearly three-decade investment of time and energy. This was also reflected in Henry's subsequent output of songs, which number three that were published from 1921 to 1923, one in 1941, and only two registered for copyrights into the 1940s. Henry's retirement was not complete, as he still consulted for Marks for several years. However, that was only part time. He made a couple of trips over the Europe in the early 1920s, and on his February, 1922, passport indicated that he was a music publisher who was temporarily retired. The countries listed for his travels were Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Italy, France, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, Holland, The Netherlands, and the UK. He made a less adventurous journey to the continent in 1924, and again in 1927.

Stern's continuing role in the Marks publishing empire, which had obtained and maintained all of the Stern copyrights, was unclear after 1924, but by the time of the 1930 enumeration Henry was listed as a real estate agent in Manhattan. Little was heard from him in the 1930s, but the 1940 census showed him still in Manhattan with Cora and his son Cyril. In 1941 the couple moved down to Dallas, Texas. From there he issued one more piece just three weeks ahead of the attack on Pearl Harbor, prophetically titled V for Victory. There are appearances of him in Dallas city directories over the next two decades. The 1950 enumeration, taken in the Highland Park neighborhood of Dallas, showed Henry still listed as a composer. They also had a live-in nurse, but it is unclear if she was a lodger, or perhaps taking care of Cora. In October of 1959, Cora left Henry a widower. Henry Stern later succumbed to cardiac failure from colon cancer in 1966, passing on at age 91. The Marks empire that he helped to forge is still strong in the 21st century, so even if not overtly prominently named as a part of that legacy, he remains an important component of music publishing history, as well as the ragtime era.

Known Compositions (all as S.R. Henry)

Known Compositions (all as S.R. Henry)