|

Wilbur Colman Sweatman (February 7, 1882 to March 9, 1961) | |||

Compositions Compositions | |||

|

1904

I'll Be Happy When I'm Thinking of You[w/C.E. Smith] 1911

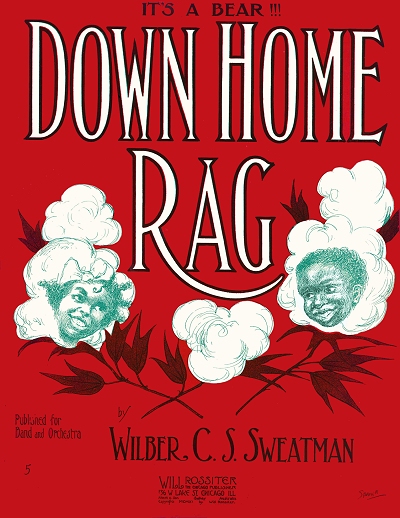

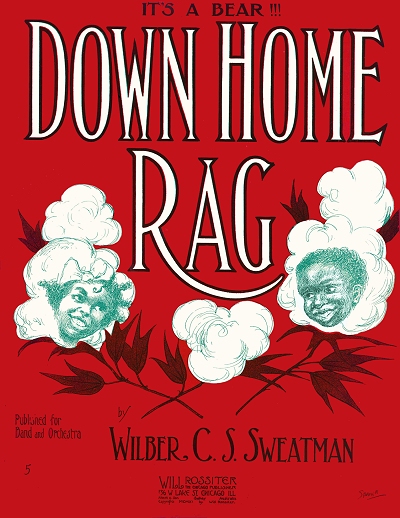

Down Home Rag1913

Down Home Rag (Song) [w/Roger Lewis]1914

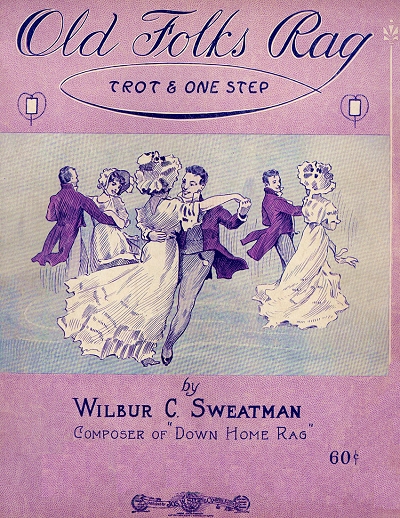

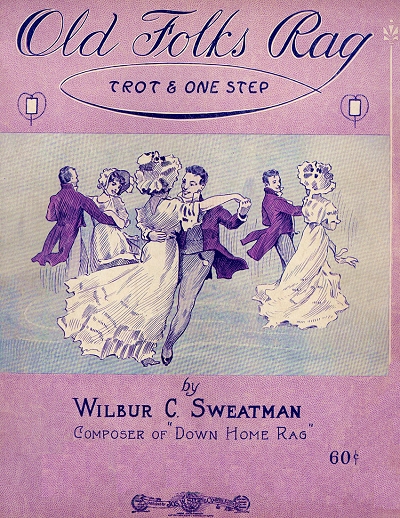

Old Folks Rag1916

Virginia Diggins1917

Boogie Rag |

1919

That's Got 'EmRainy Day Blues 1923

Battleship Kate1930

Breakdown Blues'Got 'Em Blues Sweat Blues c.1950s

Sweet ManiaFine, Fine, Fine If the World is Round, It's Crooked Just the Same Battleship Kate Cha Cha | ||

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |||

| |||

Wilbur Sweatman was born in Brunswick, Missouri, to Coleman Sweatman and his wife Matilda "Mattie" (or "Millie") in 1882. He was the youngest of three children, including older sisters Eva Leontyne (3/1878) and Linda or Lula (nicknamed "Sissie") (11/1879). Wilbur's father was a barber in Brunswick, about 60 miles east-northeast of Kansas City, but it is not certain whether either parent had been a slave. However, there is some indication that when Coleman (1853) was young, he may have been the property of Judge John Swetnam of nearby Burton Township, Missouri (now gone, but it was in Howard County).  Missouri was in a gray area literally when it came to slave ownership, part of an earlier compromise, but not all landowners participated in the practice. If this was the situation with Coleman, that would mean that once his family gained freedom, possibly upon Judge Swetnam's death in 1864, they would probably have changed the spelling from Swetnam to Sweatman to assure a combination of familiarity with and independence from their prior life.

Missouri was in a gray area literally when it came to slave ownership, part of an earlier compromise, but not all landowners participated in the practice. If this was the situation with Coleman, that would mean that once his family gained freedom, possibly upon Judge Swetnam's death in 1864, they would probably have changed the spelling from Swetnam to Sweatman to assure a combination of familiarity with and independence from their prior life.

Missouri was in a gray area literally when it came to slave ownership, part of an earlier compromise, but not all landowners participated in the practice. If this was the situation with Coleman, that would mean that once his family gained freedom, possibly upon Judge Swetnam's death in 1864, they would probably have changed the spelling from Swetnam to Sweatman to assure a combination of familiarity with and independence from their prior life.

Missouri was in a gray area literally when it came to slave ownership, part of an earlier compromise, but not all landowners participated in the practice. If this was the situation with Coleman, that would mean that once his family gained freedom, possibly upon Judge Swetnam's death in 1864, they would probably have changed the spelling from Swetnam to Sweatman to assure a combination of familiarity with and independence from their prior life. Sissie was musically trained and helped to teach Wilbur music as well. He later stated that she taught him most of his piano skills. While growing up, Wilbur started playing the violin with Sissie's piano, but eventually switched to the clarinet. It is likely in spite of his claims that he was self-taught on those instruments that he had some other training, perhaps in a school music program, as his technique proved to be very polished on the instrument. In the late 1890s Wilbur started touring with circus bands who routinely used amateurs as they were cheap. As of the 1900 census he was shown as still living with his family in Brunswick, although his father was not in the home any longer, having left and remarried in 1894, starting another family. Even though he had already been performing, Wilbur's occupation was shown as barber, perhaps having been trained by his father. Sissie was listed as a music teacher, and Eva as a school teacher. Mattie was working as a barber, and running a boarding house as well to help make ends meet.

A career with shears was soon abandoned as Wilbur picked up work with Professor Clark Smith's Pickaninny Band of Kansas around 1898. This was followed by a stint with the higher profile P.G. Lowery Band. During this time he expanded on his knowledge of the clarinet and learned how to finger two of them at once, giving himself a unique act to market and to keep employed. In 1900 and 1901 Wilbur played briefly with Mahara's Minstrels, then found work with the Forepaugh and Sells Circus Band. While in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1903, he went to the Metropolitan Music Store with a subset of that band and made two cylinder recordings. One was of E. Harry Kelly's Peaceful Henry which had become a substantial hit. The other was Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag, likely the first recording ever done of that piece. Given the limited number of cylinders made at one time, it appears that no copies of either of them exist today; only some evidence of their having been cut. Wilbur kept on playing and traveling, spending some time also with W.C. Handy in The Musical Spillers led by William N. Spiller. He also expanded his skills to playing three clarinets at one time, a feat unequaled in that era. In It was achieved by welding the tops together, using a special mouthpiece to allow air to go into all of them equally, and strapping the instruments to his thighs. Overall, the stunt was effective and gained him notoriety.

After a few years on the road, Wilbur settled for a time in Chicago playing in numerous dance bands and orchestras in the area, and eventually leading some of his as early as 1908. Given his geography and Chicago's future in jazz, it should be noted that Sweatman was, in some ways, a contemporary of cornetist Buddy Bolden, even though it is likely their paths never crossed. Both were developing some form of jazz in two very different areas of the country, yet many of Bolden's disciples would end up in Chicago after Sweatman had left the city. This becomes important when looking at the spread of the music as well as its origins, and Sweatman's role, though difficult to pin down, was of some significance. He once stated, whether jokingly or not is not known, "Don't you know I originated jazz in the Ozarks in Missouri?"  This counters the clams of "Jelly Roll" Morton and Willie "The Lion" Smith who were in New Orleans and New York respectively at that time, but makes the case that the evolution of jazz was more widespread than just in southern Louisiana, in part because of traveling musicians who would share what they knew or had heard wherever they went. Sweatman is listed in the 1910 enumeration in Chicago as a theater musician, with a slight skewing of his age, showing as 26. Shortly after, on June 29, 1910, he was married to Hazel Venie Gilmore, around nine years his junior, and known to her friends as "Nettie."

This counters the clams of "Jelly Roll" Morton and Willie "The Lion" Smith who were in New Orleans and New York respectively at that time, but makes the case that the evolution of jazz was more widespread than just in southern Louisiana, in part because of traveling musicians who would share what they knew or had heard wherever they went. Sweatman is listed in the 1910 enumeration in Chicago as a theater musician, with a slight skewing of his age, showing as 26. Shortly after, on June 29, 1910, he was married to Hazel Venie Gilmore, around nine years his junior, and known to her friends as "Nettie."

This counters the clams of "Jelly Roll" Morton and Willie "The Lion" Smith who were in New Orleans and New York respectively at that time, but makes the case that the evolution of jazz was more widespread than just in southern Louisiana, in part because of traveling musicians who would share what they knew or had heard wherever they went. Sweatman is listed in the 1910 enumeration in Chicago as a theater musician, with a slight skewing of his age, showing as 26. Shortly after, on June 29, 1910, he was married to Hazel Venie Gilmore, around nine years his junior, and known to her friends as "Nettie."

This counters the clams of "Jelly Roll" Morton and Willie "The Lion" Smith who were in New Orleans and New York respectively at that time, but makes the case that the evolution of jazz was more widespread than just in southern Louisiana, in part because of traveling musicians who would share what they knew or had heard wherever they went. Sweatman is listed in the 1910 enumeration in Chicago as a theater musician, with a slight skewing of his age, showing as 26. Shortly after, on June 29, 1910, he was married to Hazel Venie Gilmore, around nine years his junior, and known to her friends as "Nettie."While in Chicago Wilbur played and led at the Big Grand Theater on State at 31st, a large vaudeville and movie house. He also played in a trio consisting of himself with Dave Peyton on piano and George Reeves on the drums, similar to a makeup that Benny Goodman would use for some hot jazz recordings 25 years later. There were many players from that time that recall the level of influence Sweatman had on them, including future jazz player/composer Perry Bradford who cited his style as covering the full range of dynamics from smooth to growling. Other Chicago venues included the famous Pekin Inn, musical home also to composer/pianist Joe Jordan, and the Monogram Theater.

His programs included a wide variety of styles, ranging from classical and gypsy tunes to hot syncopated takes on contemporary compositions. In 1911 Wilbur brought out his first rag with publisher Will Rossiter, Down Home Rag. It was unusual in that it consisted entirely of only eight measure sections of 4/4 instead of the traditional sixteen in 2/4. This suggested a different feel than the common duple meter found in ragtime, and was a precursor to how many early jazz pieces would be scored. A song version of Down Home Rag was published by Rossiter two years later due to its growing popularity. The credit for the instrumental piece is listed as Wilbur C. S. Sweatman, although there is no convincing evidence outside of this that he actually had a middle name starting with S, making this an anomaly and perhaps a publisher's error. The song edition listed him only as Wilbur C. Sweatman.

Wilbur went on the road in 1911 on one of the eastern vaudeville circuits, and by 1913 had decided to make New York City his home base. An example of the type of bill Sweatman was on could be seen in one of the frequent New York Times entertainment listings such as this one from October 1913. "In addition to Wilkie Bard at Hammerstein's, the bill there this week includes Fatima, the Persian slave dancer, who remains for a third week. Others on the bill are Windsor McCay, the cartoonist [likely with his animated Gertie the Dinosaur]; the Farber Girls, two singing comediennes; Madden and Fitzpatrick in a comedy number; Sherman, van, and Hyman, singers and musicians [likely Gus Van, later of Van and Schenck]; Wentworth, Vesta, and Teddy, comedy acrobats; Stewart Sisters and Escorts from the Alhambra, London; Wilbur Sweatman, clarinet virtuoso and comedian; Savo, 'a juggler for fun,' and Cadieux, comedian on the bounding wire."

|

The clarinetist soon became a staple in the theaters there, leading his own orchestra by 1914 at the newly opened Lafayette Theater in Harlem. Wilbur also had the honor of a three week stint at the large vaudeville house, Hammerstein's Victoria, built in 1899 by Oscar Hammerstein Sr. Even though Sweatman was based in New York, he spent much of the next two decades on the road during part of the year, playing all across the United States. During his first few years in New York, Wilbur became friends with ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who was on the decline from 1915 to 1917 when he died. Joplin had enough trust in Wilbur that he made the clarinetist the executor of his estate, meaning that all of the copyrights and disposition of remaining paperwork not controlled by Joplin's wife Lottie would be handled by Sweatman. Wilbur did his best to honor this, but there would be unfortunate repercussions decades later.

The next step for Sweatman was to get into the recording studio. His first New York sessions yielded two takes of his own Down Home Rag and two takes of My Hawaiian Sunshine by L. Wolfe Gilbert. Many historians argue that the loose feel and hints of improvisation found in Down Home Rag posture it as one of the earliest examples of recorded jazz, preceding the Original Dixieland Jass Band's first record by two months. It was issued by Victor Emerson who had left his job at Columbia the year before, following two decades with the pioneering company, to form his own Emerson Records. Emerson had seen the demand for inexpensive but well made records, and resolved to cater his product to the masses, much as Henry Ford had done with the Model T. Two of the cuts were made on relatively small 6" discs using a universal 45 degree cut that was supposed to work on both vertical (Edison) and lateral (Victor) players. The end result was only fair sound quality for each system, but it is still a good representation of Sweatman's work, even at an average of 90 seconds per cut. The other two were done on more conventional 7" double sided records.

Wilbur's next series was made in the spring of 1917 on the Pathé label with a group of five saxophones, similar in makeup to the Brown Brothers group which was starting to make a name for itself and may have influenced this session. This unusual combo of one bass, one baritone, one tenor and two alto saxophones under Sweatman's clarinet yielded some gems, including A Bag of Rags and Boogie Rag, one of the first pieces that included the word Boogie in the title. One other piece in this set was also fairly important. In W.C. Handy's autobiography he writes: "It was difficult to get 'Joe Turner [Blues] recorded. I came to New York for that purpose and while walking down Broadway I met my old friend Wilbur Sweatman - a killer-diller and jazz pioneer. He invited me home with him, and his wife Nettie prepared a lovely dinner. While dining she turned on the phonograph, and lo and behold it played 'Joe Turner Blues' which Sweatman had recorded not only on the Pathé but Emerson records also." This was not entirely accurate as the Emerson cut was made by that company's own Military Band, but it does underscore Sweatman's importance even to a high-profile musician like Handy. These recordings are also among the first to use the bass saxophone, soon to be a staple in jazz recordings. Also in 1917 Wilbur Sweatman became one of the first black musicians to join ASCAP.

Sweatman's draft record from the September 12, 1918, last call, taken in Manhattan, showed him working as a vaudeville performer, employed by Bruce Duffus, who was located in the Putman Building on Broadway in New York City. Curiously his first name was spelled as Wilber, including in his signature, the only time this was seen. His middle name was written as Coleman, but the e was obliterated, perhaps a move to distance himself from his father. His 1942 draft record showed it as Colman. Wilbur recorded again from 1918 to 1920, this time for Emerson's former employer, Columbia Records, The 34 or so sides cut with his Jazz Orchestra (many of the masters have since been lost) were among the first true jazz recordings by an African American group, and cover a wide variety of songs and popular instrumentals for the era. Some were also released on the subsidiary Little Wonder label.  Notable tracks include Euday Bowman's Kansas City Blues and Regretful Blues by Cliff Hess. In short order Sweatman was billed as the "Originator and Much Imitated Ragtime and Jazz Clarinetist," which in spite of the hyped ad copy was a relatively accurate statement. Yet after the success of the ODJB, and subsequent recordings by the Original Creole Orchestra, there is some clear change in Sweatman's style, a little wilder and looser than it had been before.

Notable tracks include Euday Bowman's Kansas City Blues and Regretful Blues by Cliff Hess. In short order Sweatman was billed as the "Originator and Much Imitated Ragtime and Jazz Clarinetist," which in spite of the hyped ad copy was a relatively accurate statement. Yet after the success of the ODJB, and subsequent recordings by the Original Creole Orchestra, there is some clear change in Sweatman's style, a little wilder and looser than it had been before.

Notable tracks include Euday Bowman's Kansas City Blues and Regretful Blues by Cliff Hess. In short order Sweatman was billed as the "Originator and Much Imitated Ragtime and Jazz Clarinetist," which in spite of the hyped ad copy was a relatively accurate statement. Yet after the success of the ODJB, and subsequent recordings by the Original Creole Orchestra, there is some clear change in Sweatman's style, a little wilder and looser than it had been before.

Notable tracks include Euday Bowman's Kansas City Blues and Regretful Blues by Cliff Hess. In short order Sweatman was billed as the "Originator and Much Imitated Ragtime and Jazz Clarinetist," which in spite of the hyped ad copy was a relatively accurate statement. Yet after the success of the ODJB, and subsequent recordings by the Original Creole Orchestra, there is some clear change in Sweatman's style, a little wilder and looser than it had been before.The Music Trade Review of May 3, 1919, announced that: "Wilbur Sweatman, the well-known musical director, who is also responsible for many of the jazz phonograph records, has been engaged to piay a series of concerts at the Eltinge Theatre, New York, with his jazz orchestra. The first of these took place on Sunday last, consisting of a specially selected program of up-to-date successes, among which were featured S. R. Henry's latest success 'Pahjamah,' 'Tishomingo Blues' and 'Corinne.' After his New York engagement Mr. Sweatman and his orchestra will probably tour the country." He was also a smart entrepreneur as just a month before the same paper announced that: "Wilbur Sweatman, well known as an orchestra leader for talking machine companies, has purchased an interest in the Triangle Music Co., New York." It was an effective method to counter royalties paid out on some of the pieces he recorded, and assured him of an outlet for his own works, though it was rarely used in that way since his output was minimal.

Sweatman was the top clarinet artist on Columbia until white artist Ted Lewis, of only better than average ability, took over that role early in the 1920s. Still, Wilbur had his New York admirers as well. Clarinetist Garvn Bushell remembered that "Wilbur Sweatman was a clarinetist with a lot of technique that could to things the rest of us couldn't do. He had a bad sound, but he was a great showman. He'd come out and do Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 and play The Rosary on three clarinets. Sweatman was my idol. I just listened to him talk and looked at him like he was God." As of the 1920 census Wilbur and his wife Nettie were living in Manhattan, sharing their lodgings with a few other people, with his occupation listed as band leader. Within two weeks of the census he was performing with his group in Chicago and would be there through most of the winter.

While Sweatman took a break from recording in the early 1920s, he was still very active as a performer. Having been friends with Perry Bradford for a while, he helped Bradford get a lady singer friend an audition with Columbia. While she did not get a contract with them, at least Mamie Smith had been heard, and ultimately recorded on the OKEH label. Sweatman did record again in 1923 and 1924 for Gennett. One young piano player who had come up from Washington, DC, had been working with Sweatman's band for a short time when Wilbur went into the studio. However, there is still controversy as to whether that pianist, Duke Ellington, is the one heard on a 1923 recording of Sweatman's composition Battleship Kate, a piece that Sweatman recorded many times.

Other musical luminaries who either got their start with Sweatman's band or at least worked with him included Otto Hardwick [bs], Sonny Greer [dr] who would end up with Ellington, Cozy Cole [dr], Jimmie Lunceford [tsx], and Coleman Hawkins [tsx], who would become a major star in his own right.

Hawkins was with Sweatman when they played at the opening of the famous gangster-run venue Connie's Inn in June, 1923. short-lived group, his Acme Syncopators, cut one side for Gennett in September of 1924. The following month he traveled up to the Edison studios to cut two sides as Wilbur Sweatman's Brownies on a Diamond Disc.

|

Throughout the 1920s and into the Great Depression, Sweatman swung his clarinet up and down Harlem and even down into Manhattan, with occasional tours throughout the eastern half of the United States, most of which were heralded with enthusiastic advertising in local newspapers. He may have dabbled in stage work as well, as the 1930 enumeration listed him as a theater actor. However, this is likely common a miscasting by the census taker as Sweatman was traveling on the Keith vaudeville circuit with a nine-piece jazz band. He also was listed as married and living in Harlem on West 138th Street, but his wife was not shown on the same page. They may have been separated by this time or he had another home elsewhere where she was living.

Following a mild resurgence of the popularity of traditional jazz, Wilbur did his last set of recordings on the Vocalion label in 1935, cutting four sides of 1920s style jazz, perhaps his last hurrah as a recording artist. He curtailed most of his playing late in the decade to focus more on the music publishing and talent booking business, but still played from time to time at Paddell's Club with a trio, and elsewhere throughout New York City as a guest with swing bands. There were numerous radio appearances by Wilbur as well.

As of the 1940 census Sweatman was living in south Harlem at 371 120th Street, along with two lodgers, Dorothy Smith, a doctor's receptionist from Washington, DC, and her twelve-year-old daughter Chalita Hudnell. He was listed as an orchestra musician. By 1942, Wilbur and Dorothy, who was 28 years his junior, were married, although likely by common law. They had a daughter born out of wedlock several years early named Barbara, who would become a point of legal contention after his death. Wilbur's occupation on his draft record was as a self-employed orchestra leader, but he also ran a theatrical agency around that time. By the early 1950s he had all but hung up his clarinet and started his own publishing firm located at 1674 Broadway. Sweatman subsequently put out a few pieces of his own and his colleagues. Early in that decade Wilbur was in a nasty auto accident that partially incapacitated him and slowed him down considerably.

Wilbur Sweatman died in 1961, but some of his troubles were left behind. In his home was a trunk of musical memorabilia of considerable importance, including a report of an army duffel bag that contained manuscripts of unfinished and/or unpublished works by Scott Joplin. The contention about the status of Scott Joplin's estate through his wife Lottie at that point, much less Wilbur's, went into the courts. His sister Eva and his illegitmate daughter Barbara had a legal tussle over his estate for some time, and many of the physical elements of it fell into disarray or were victims of poaching or poor storage. Eventually, much of it disappeared, although how is unclear, as is the disposition of items such as the chest of treasures. It was reportedly disposed of by Barbara. With it went much valuable material by not only Sweatman, including his unpublished autobiography, but by Joplin as well. Had this material still been available in the late 1960s as researchers started to do serious work on Joplin's life would have potentially expanded our early knowledge base on both of these ragtime composers, particularly Joplin's work in his later years.

Those who remembered Wilbur were also often less than generous in their assessment. Having been a black recording artist at a time when the ODJB, a white group, was making a big splash with "their" new sound, helped to squelch his press, and the loss of many of the Columbia masters, already of questionable quality, plus the disappearance of Emerson and Pathé further buried his potential to be regarded as an early jazz great. Even though he did see renewed fame in the 1950s with the resurgence of traditional jazz and the rediscovery of ragtime, in addition to many cover recordings of Down Home Rag, it may be the latter factor that led to him being cast more in a ragtime mold than jazz. Yet in many ways, his influence was echoed by many who carried on what they had learned from Wilbur in their own recollections and performances.

Some of this biographical information was researched by Mark Berresford, and included on a stellar double CD recording that covers the bulk of Sweatman's recorded work from 1916 to 1935. Some additional information comes from 1950s articles by Len Kunstadt and Bob Colton. Judge Sweatnam's great great grandson Richard Swetnam also weighed in about the possibility of Colman having been the property of his ancestor at one point. The remainder was researched by the author in public records, periodicals, newspapers, legal papers and recording logs.