|

Spencer Walter Williams, Jr. (October 14, 1886 to July 14, 1965) | |

Known Compositions Known Compositions | |

|

1909

For You Are My Love in Zulu Land1911

My Little Moonlight MaidThat Surely is One More Rag [1] I'm Thinking of You All the Time [2] It is You That I Love To-Day [3] 1912

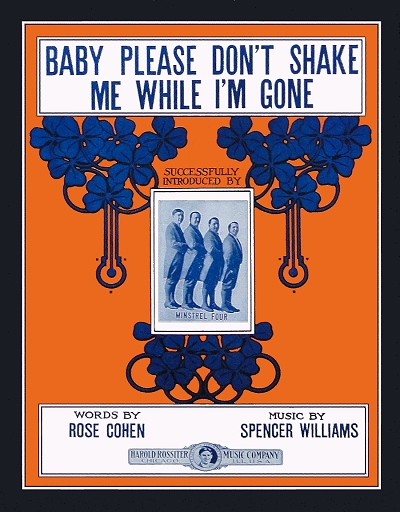

Baby Please Don't Shake Me While I'm Gone [4](Variants include "Shake It" and "Trifle") The Whole Day Through [5] 1913

Down in Shenandoah Valley [6]My Little Moonlight Maid (Redux) [7] Mechanical Lovin' Man [8] 1914

In the Woodland of Love [6,7]1915

I Ain't Got Nobody Much (and Nobody Caresfor Me) [9] At the Alabama Cotton Ball 1916

Shim-me-sha-wabbleMy World of Pleasure is to Be Alone With You You'll Want My Love I Ain't Got Nobody (Retitled/Recredited) [9,10] Paradise Blues (When You Play the Blues I'm Right in Paradise) [11] 1917

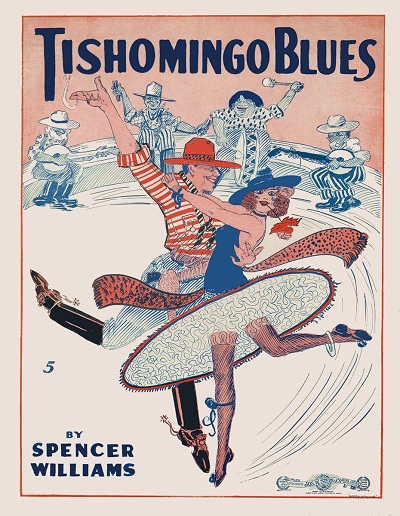

Tishomingo BluesSteppin' on the Puppy's Tail Showin' Yo' Shot Daddy, I Ain't Mad at You That Ragtime Symphony Band [10,12] Why Don't You Try to Get Along with Me? [11] I Never Had the Blues Until I Left Old Dixieland [11,13] The Cocaine Dance [14] 1918

Full o' Snap: Fox TrotKeeps on a Rainin' (Papa He Can't Make No Time) The Frisco Walk Since They Learned to Shimmie Down in Honolulu Three Pickanninies (How About a Little Harmony) Ringtail Blues [15] The Message from Home [15,16] Melancholy Blues - The Yodlin' Blues [15,17] Pipe Dream Blues [15,18] You'll Never Miss My Love, Until I'm Long, Long Gone [19] Wait Until Your papa Comes Home [19] Down Where the Rajahs Dwell [19] At the Ragtime Stroller's Ball [20] Keep Your Eye on the Old Back Seat [21] 1919

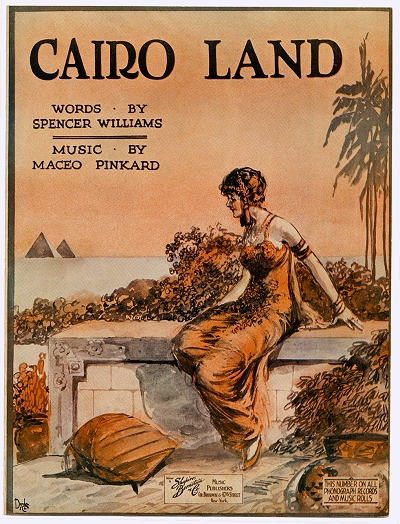

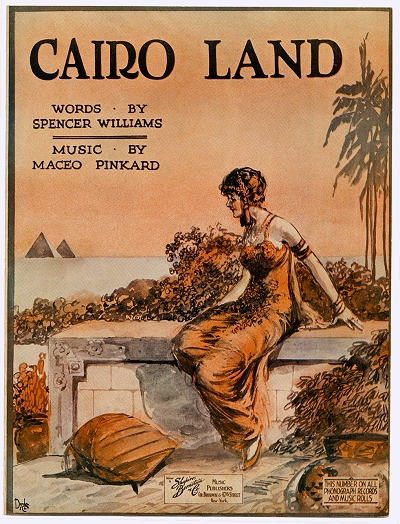

Kune-JineDaigah's Dream: Brazilian Intermezzo I Want to Call You Papa M'Liss Beautiful Sunshine Lost John's Melody: Fox Trot I'll Get Him Yet Big Fat Ma You're Mammy's Blackberry Pie You Broke My Heart with Your Eyes [6] Sweet Somebody of Mine [20] I Ain't Goin' to Give You None o' This Jelly Roll [22] Who Made You Cry, Sugar Babe? [22] Trix Ain't Walkin' No More [22] Yama Yama Blues [22] Royal Garden Blues [22] Cairo Land [23] Tishomingo Bound [24] Why Don't You Try to Get Along with Me? (Redux) [24] Don't Mind Cryin' Blues [43] 1920

Bugle BluesSnag 'em Blues I'm Gonna Love You, Ain't Gonna Let You Alone Roumania [9,22] Struttin' Yo' Stuff [20] The Dance They Call the Georgia Hunch [22,25] Mississippi Bound [24] Barcelona [26] Jungle Blues: A Tarzan Oddity [26] California Blossom [26] My Sunshine Girl: Jazzsensation [26,27] Church Street Sobbin' Blues [26,27] I'm a Sister to the Vamp [28] Milani Shore [28,29] Sandman Blues: Log Cabin Lullaby [30] Log Cabin Land [31] Tee-Roller Blues [32] 1921

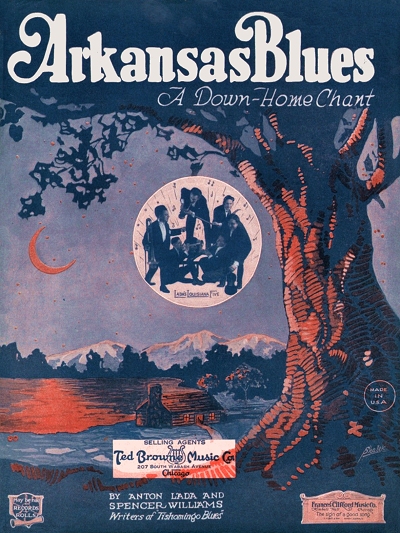

My June Love (The Sweetest Honeymoon Love)Put and Take The Land of Creole Gals Shoulder Chocolate Brown Wild Weepin' Blues [23] Blue Flame: Fox Trot Ballad [26] Neglected Blues: A Love-Sick Wail [26] He's My man, You Better Leave Him Alone [26] Arkansas Blues: A Down Home Chant [26] Manila Bay [26] Someone's Put the Jinx on Me [26] It Took a Wild, Wild Woman to Make a Tame Man Out of Me [26,33] Japo Blues: Fox Trot [34] Josephine [35,36] Mississippi Blues [37] You'll Want My Love (Redux) [37] Hey! Hey! [38] Many a Day [39] In My Heart [39] Pensacola Blues [40] Some Time, Some Day [41] Dream Bird [42] 1922

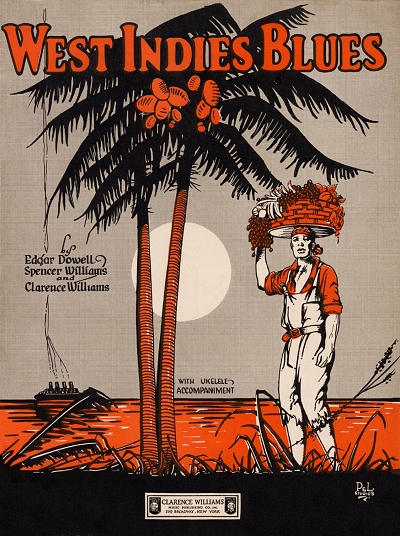

Loose Feet (The Dance of Blue Goose Pete)Struttin' at the Strutter's Ball Black Cat Luck The Meanest Man in the World Your Time Now 'Twill Be Mine After a While Alibi Blues It's the Last Time You'll Ever Do Me Wrong Another Blues: A Blues that Moves Your Shoes Achin' Hearted Blues [22,43] West Indies Blues [22,44] State Street Blues [35] She Walked Right Up and Took My Man Away [35,45] Got to Cool My Puppies Now [35,46] Flapper Fan: Novelty Song [46] Parting: Waltz [46,47] Come on Down to Tinkle Town [46,47] Dear One [46,47] The Apple Sauce Blues [48] Stop Aggravatin' Me [49] 1923

Cotton Belt Blues: Mamma's Sorry SongTired o' the Blues: Mournful Mamma's Wail You're Always Messin' 'Round with My Man Spider Low Down Papa Snakes' Hips: A Jungle Jazz Those Lazy Blues Keep Yourself Together, Sweet Papa (Mama's Got Her Eyes on You) Tell Me, Gypsy, Where My Lovin' Daddy's Gone Black Man, Be On Yo' Way I'm a Good Gal But I'm a Thousan' Miles from Home Turned Down Papa Blues Three Pickaninnies: Darkomedy Easy Going Brown Skin [22] Nobody in Town Can Bake a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine [22] Dreary Weary Blues [26] Chicago Blues: A Twentieth Century Chant [29,142] Tut-Ankh-Amen [33] Midnight Blues: A Wee Hour Chant [35] Just One More Day [35] There Never Was a Girl Like You [35,54] Haitian Blues [45] Miss Minnie Wiggle [50] Cemetery Blues [51] Scandal Blues [52] The Duck's Quack [53] Keeps On a Rainin', Papa He Can't Make No Time [60] 1924

Banjo Blues: Blue Man Sam's LamentHoodoo Blues: Conjure Woman's Lament Tombstone Blues Box Car Blues Chain Gang Blues Poor House Blues Mountain Top Blues Mississippi Delta Blues Louisiana Low Down Blues Papa Tree Top Blues Family Skeleton Blues Western Union Blues How Can I Get It, When You Keep on Snatchin' It Back? Jamaica Gal Get Away from My Window, Don't You Knock at My Door Ticket Agent Ease Your Window Down Snatchin' it Back? When I Get the Devil in Me Ukulele Ike, He Sure Can Uke a Uke Strut Yo' Puddy I Can Do What You Do Dictionary Blues [22] Here They Come [22,54] I'd Rather be Blue than Green [22,54] Papa-De-Da-Da: A New Orleans Stomp [22,55] Cast Away [22,55] Lonesome Monday Mornin' Blues [37] Raisin' Cain [46,56] Black Star Line: West Indian Chant [44] Hot Dawg! Fox Trot [53] My Sweet Baby Irene [54,57] An Awful Lot My Gal Ain't Got, But What She's Got, She's Got an Awful Lot [57] Bloody Razor Blues [57] Ramblin' Papa Blues [57] Bullet Wound Blues [57] I May Be a Little Green But I Ain't No Fool [57] Every Sweetie That I Get, Somebody Takes Her From Me [57] That Blue Strain [57] Flat Tire Papa, Mama's Gonna Give You Air [57] Ghost Walking Blues [58] Everybody Loves My Baby (But My Baby Loves Nobody but Me) [59] Give Me Just a Little Bit of Your Love [59] I'm a Good Gal, But I'm a Thousand Miles from Home (Redux) [60] Log Cabin Blues [61] Ramblin' Till I Find My Lovin' Man [62] Shook Him an' Took Him [63] Mississippi Blues [64] If You Can't Ride Slow and Easy, I'll Have to Put You Off My Train [65] My Sugar Man [66] Mad Mama's Blues [67] Undertaker's Blues [67] 1925

Montmarte GigglesDance With Me Cross-Word Crazy Suicide Blues Crepe Hanger's Blues Cheatin' Blues Dang'rous Blues Heartless Woman Blues Hock Shop Blues Rock Pile Blues Good Time Flat Blues (Farewell to Storyville) Rough House Blues: A Reckless Woman's Lament Shipwrecked Blues Sore Bunion Blues Pig Alley Stomp Get It Fixed I Can't Keep Away from Honey and My Honey Can't Keep Away from Me Mama is Waitin for You No One Can Love Me Like the Way You Do My Good for Nothin' Man You're in Wrong with the Right Baby if You Wanna Kiss Yourself Good-Bye [23,68] Hot Eskimo [46,69] Trinidad [46,47,70] Workin' Woman's Blues [57] Brother Ben [57] I'm Gonna Hang Around My Sugar Till I Gather All the Sugar That She's Got [59] She's My Sheba, I'm Her Sheik [59] If I Had My Way 'Bout My Sweetie [59] Last Journey Blues [67] North Bound Blues [67] Bitter Feelin' Blues [67] Penitentiary Bound Blues [67,71] Thunderstorm Blues [71] Trombone Blues [72] Old Norwegian Blues [72] Stolen Kisses are the Sweetest [73] Glad Days, Bring Back Those Glad Days [73] Eastman [74] 'Neath the Palms [75] Waltz of Love [76] Whoop it Up and Break it Down [77] Everything My Sweetie Does Pleases Me [78] 1926

Liza JaneWe Won't Go Home 'Till Mornin': Gang Song Chinky Winky Chinese Rag Levee Blues The Prisoner's Blues Down Old Georgia Way I've Got Somebody Now Ain't Nothin' Cookin' What You're Smellin' The Beggar's Song High Steppin' Dandies from 'Bam Georgia Grind Charleston Cabaret The Engineer's Last Request No One Can Love Me Like the Way You Do What's the Matter Now [22] Take a Little Walk with Me [22] Dancing Girl [22] I Don't Like it Second Hand [22] Bath Tub Blues [22] Crazy 'Bout That Man I Love [22,57] Señorita Mine [22,57,79] Charleston Hound [22,57,79] That Struttin' Eddie of Mine [22,57,79] West Virginia Blues [52] Oh Honey Babe [55] I've Got You and You've Got Me [55] Sugar! What's Your Name [59] I've Found a New Baby [59] Who Does My Baby Love? [59] I Had a Good Gal But I Lost Her [59] I'm Asking for Some Loving from You [59] That's Her [59] I'm Gonna Take My Bimbo Back to the Bamboo Isle [59] Burn 'em Up Sadie [59] Boodle Am [59] Bridge of Sighs [73] I'm in Love Again [80] I'm Saving it All for You [81] I Nearly Had Him, I Nearly Got Him, But He Was Already Had [82] San Domingo Bay [82] You'll Do, Doodle-Do for Me [82] Lindy Lou [83] Stockyard Blues [83] If You Don't Let Me in This House, Don't Let Nobody Out [83] Windy City Blues [83] Skeedle Um [84] Lonesome Love-sick Blues [85] Careless Love (Transcription) [86,87] Jamaica Blues [88,89] 1927

Orn'ry BluesCan't Be Trusted Blues Wayward Roamer Blues If You Know What I Know [85] Black Bottom Ball [85,90] I Love Dancing [85,90] Saushay Middlin' Swing [85,90] Gold [90] Piano Man [90] Wa-wa-wa: Cornet Blues [90] When I March in April with May [91] What Have I Done? [92,93] 1928

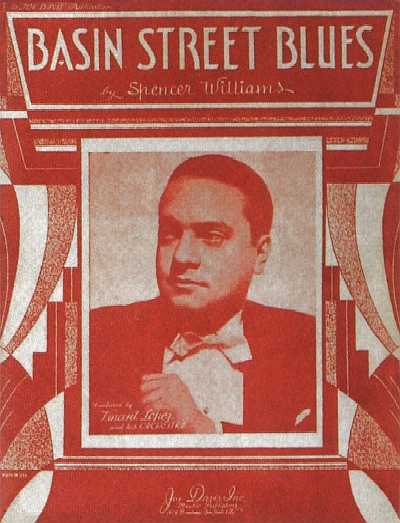

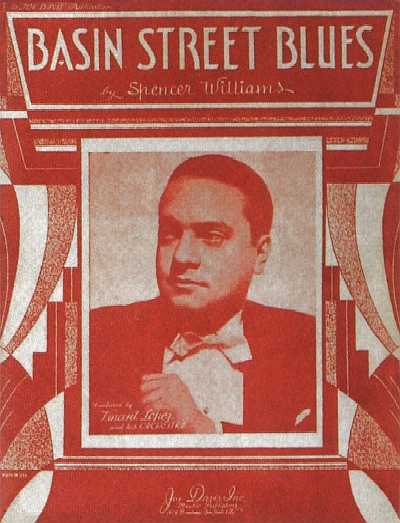

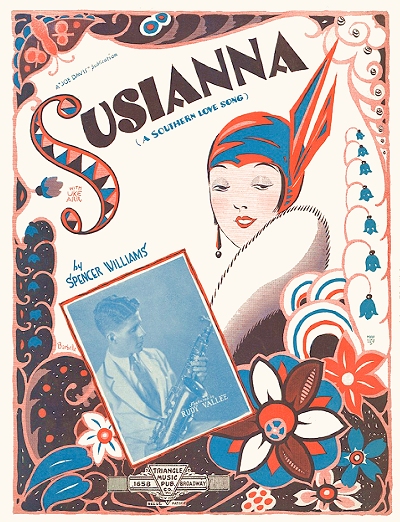

Slow Poke BluesSolitaire Solitude (A Weird Inspiration) Wednesday Night Waltz Susianna: Southern Love Song Echo Blues Toad Frog Blues Lame Duck Blues Blind Pig Blues Dreamy Everglades Skip the Gutter Melancholy Yodel Blues Swanee River Ripples Waycross Georgia Blues Low Down Rounder's Blues Alligator Blues Country Woman's Blues Southern Breeze Washwoman's Blues Nameless Blues Spanish Fort Blues Swanee Blue Jay Chittlin' Rag Blues Deck Hand Blues Drowsy Moonlight Railroad Porter Blues 'Sippi Signs Put on the Brakes Tennessee Mountain Gal Blues Dixie Shadows Bear Behind Blues Fireworks: A Rhythmic Explosion Knockout Notes Mississippi Woman Blues Fast Fadin' Papa, You're Fadin' Too Fast for Me She is My Honey and I am Her Bee Sweet Somebody of Mine [20] Treat Me Right While You Got Me, Or You Won't Have Me Long [22] If You Like Me, Like I Like You [22,57] Georgia Gut [54] Heaven on Earth [59] Where [59] You Can't Take My Mem'ries from Me [81] A Blind Mother's Prayer [81] My Tennessee Mountain Home [81] Dreamy Waikiki [81] Who's That Man? [87,95] Mellow Moonlight [95] Have You Ever Felt That Way? [95] Talkin' 'Bout Home [95] Basin Street Blues [96] Sweet Hawaiian Dream Girl [97] Shake it Down [98] Sweet Mignon [99] Syncopated Yodelin' Man [100] Jazbo Dan and His Yodelin' Ban' [100] Someone's Teaching Me How to Forget [100] Prancin' Dancin' Fool [101] I Want a Good Man, and I Want Him Bad [102] Where is My Man? [103] My Spanish Cameo [103,104] Furniture Man Blues [105] Little Miss Vanity: Waltz Song [143] 1929

Mahogany Hall StompYou've Got to Give Me Some Bad Time Blues Down Home Dance Cold Wave Blues Crazy 'Bout My Lollypop Magnolia Blues If Feels So Good Miss Meal Cramp Blues I'm Wild About That Thing Tell Me When Blues Broncho Bustin' Blues Arizona Blues African Jungle Prairie Blues Happy Rhythm: Fox Trot Garlic Blues Beggin' for Love Utah Mormon Blues Creole Love Song Sundown Blues Death is on Your Track |

1929 (Cont.)

Nappy-Headed BluesPresident Hoover March [as William Spencer] You Don't Understand [22,94] Why Am I Alone with No One to Love? [54,57] It Ain't No Fault of Mine [81] Blue Ridge Sweetheart: Waltz [81] Pretty Face [81] If You Were Mine [81] Sparkling Waters of Waikiki [81] The Blues Singer from Alabam' [95] Georgia Gigolo: Novelty Song [106] Let's Pass the Night Away [107] Ma Petite [107] Save a Little Kiss for Me, Chérie [107,108] May I Bring You Flowers, Mademoiselle? [107,108] 1930

Moan, You Moaners!: A Syncopated SermonGhost Creepin' Blues Pick 'em For Me Papa Blue Spirit Blues Disgusted Blues Jungle Drums Insane Blues Monkey and Baboon Cold-Hearted Blues That Makes Me Give In Worn Out Papa Blues Ain't Got No Worry, As Long as You're My Baby Arkansas Moanin' Blues Texas Twist Tampa Twirl Down in the Delta Blues Sweet Candy Man The Golliwog's Parade Race Horse Blues Sweet Like So When a Black Sheep is Blue for Home Patting Dat Cat The Goose and the Gander Blow It Up Evil-Hearted Blues Clean It Out The Bullfrog and the Toad Where is the One I Love? My Rocky Mountain Home The Chicken and The Worm Watchin' and Waitin' Blues Cross-Eyed Blues Where is the One I Love?: Ballad Mister Mitchell, I'm Crazy 'Bout Your Sweet Poontang You're So Endearing The Spider and the Fly I've Lost My Head All Over You My Man o' War: Novelty Song [54] Baby, It Upsets Me So [54] Can It Be True? [54] Chiropractor Blues [54] I'm a Stationary Woman, Lookin' for a Permanent Man [54] Left All Alone with the Blues [94] Wait Until We Get Alone [94] Can This Be Love at Last? [109] Let's Get Familiar [109] Timba Tamba Timbuctoo [109] Shakin' It All Night Long [109] Weepin' Like a Willow Tree [109] Wonder: Fox Trot [110] Hawaiian Lullaby [111 Springtime, Lovetime, You: Waltz [112] 1931

Black Skunk BluesThe Hobo's Air Got Religion in My Soul Glory! Glory! I'm a Sap [54] My Home in Oklahoma [81] Bill the Life Saver [81] Little Rosewood Casket [81] Just a Crazy Song (Ha-Ha-Ha, Ho-De-Ho) [113] 1932

I'm Wild About That ThingElectrician Blues Sighin' for the Southland Where I Belong On Resurrection Day: Spiritual Waitin' 'Till My Baby Comes Home Having a Halloween Ball I Want You to Know I Love You Do Me a Favor, Lend Me a Kiss [54,57] You're My Ideal [57] The Blowin' of the Breeze Blew You Into My Arms [57] Where the Dew Drops Kiss the Morning Glories Good Mornin' [57] Keep It to Yourself [81] The Hills of Tennessee are Calling Me [81] With All My Heart [114] The Lion's Roar [114] Thompson's Old Grey Mule [115] Bring 'm Back Alive [77,116,117] 1933

Driftin' Tide, I'm as Blue as I Can BeSong of the Flood I Want You to Know I Love You Down on the Delta: Fox Trot [57] You're Breakin' My Heart [57] 1934

Keep It to Yourself [81]1935

You Shouldn't Be Bashful [77,116]Take That Train to Texas: Hot Fox Trot [77,116] Let Me Know [77,116] You've Gotta Swing It when You Bring It [116, 118] Saturday Night on Sugar Hill [116,119] Trouble in My Heart [116,119] Two Sweet Lips [116,119] Sous le Ciel d'Afrique ('Neath the Tropic Blue Skies): Slow Fox Trot [120] Le Chemin du Bonheur (Dream Ship) [121] 1936

Benny Sent Me [57]Shakin' It All Night Long [57] Dere's Jazz in Dem Dere Horns [116] Moon Mist [116] When Lights are Low [122] 1937

Barbary Coast BluesLullaby Your Lady Canal Street Chant Dinner's Ready in the Dinin' Room Singing You Out of My Heart [116] Tell Me It's Not Wrong to Love [116] Rubberlegs [116,123] My Gal's in Town Tonight [116,123] Just a Mood [122] 1938

Ma Little Kinky HeadStolen I Got Love [57] What a Pretty Miss [57] I'm Gonna Fall in Love and Marry You [57] Not There, Right Here [57] A Cottage in the Rain [57] I've Got You Where I Want You [57] Bluer Than the Ocean Blues [57,124] Great Camp Meetin' Ground [81] You're the Type [124] Swinging the Irish Reel [124] Pent Up in a Penthouse [124] 1939

You Can't Have Your Cake and Eat It [57]When Penelope Prim Passes By: Waltz [124] I'm Sending a Letter to Santa Claus [125] 1940

I'm Praying Tonight for the Old Folks at HomeSpringtime: Waltz Got to Have It All the Time An Old Shakespearean Music Box Yankee Marseillaise Port Arthur Blues: Novelty Piano Solo Forget-Me-Not Devil Can't Hurt Me [54] Georgia Blues [81] Georgia Lullaby [81] Eastman (Natural Born Eastman Don't Have to Work) [124] Mazeltov: Fox Trot [126] 1941

I Miss You in the MorningSanta Claus is Bringing You Home for Christmas 1942

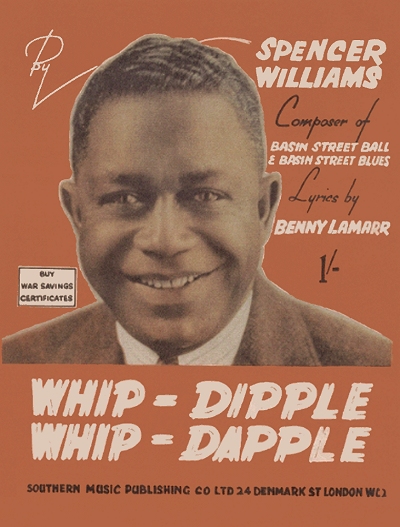

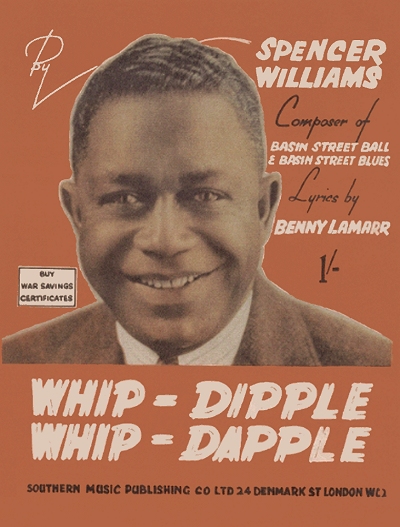

Where Carnival Dances at the Mardi GrasWhip-Dipple Whip-Dapple Soft Shoe Shuffle Basin Street Ball [127] It's the Bluest Kind of Blues My Baby Sings [144] London Conga [145] 1943

Blues Aroun' my BedShoe Shine Gal [127] Soft Shoe Shuffle [128] 1944

Blue Train BluesComin' Throught (For Me and You) On the Bridge of Avignon [129] Arms for My Man [130] 1945

This is the Night for RomanceMama-Mama-Mamanita, Papa-Papa-Papapita Chattanoogie Boogie Express Someone Else is Singing You My Love Song 1946

Delta Dreams (The Bluest Kind of Blues)Jazz Comes Home from War Red Lips Spencer Williams' Album of Blues: Basin Street is Basin Street Again Blue Down-Hearted Blues Harlem Hurdy-Gurdy Beulah (Baby Your Mouth's Too Big) Mahogany Hall Mood Basin Street Bounce [146] 1947

I'm Tired but I Don't Want to Sleep [131]It's a Crooked Cockeyed World [132] Around About Love Time [133] Only a Dream Away [147] 1948

Shut-Up-Mouth SwamplanThe Swedish Hambo Diamonds Tumbled Down on Dixie There's a New Day a-Comin' Bye 'n' Bye Stevedore Slave Song It's Your Own Fault Nobody Loves You Rio in the Moonlight [124] 1949

The Face on the Toy Balloon [134]1950

Closer! Closer! Closer! Closer! (When YouDance with Me) Darling of Kappa Sigma Kappa Deep Blue Sea Make Me Love You All the Time My Dream Isle of Delight South Sea Samba Sugar is Sugar, Salt is Salt Arturo the Burro Tampico Shorty's Blues I Love You, I Do Four Hundred and Eight Combination The Ghost of Ol' Man Mose There's Nothing Greater Than a Prayer [135] Bienville Street Blues [136] Buck Dance [137] 1951

Broke and Busted BluesPlease Take Me Back Again Whispers in the Wind [78] The Magic of Love [138] Beautiful Rose Waltz [138] Stars in the South [138] 1952

Game of ChanceI'm Walking in the Light of Your Love Tell Me It's Not Wrong to Love (Redux) Minstrels in Town [139] Sunny Skies [139] 'Twixt 'Tucky an' Tennessee [139] Sorry for Myself [139] 1953

The Miracle of Christmas [140]1955

Sim-sala-bimYou'll Kiss and Run Away Heartaches in My Heart Piano Playin' Papa Who Taught You to Kiss [141] 1957

Gave My HeartChillun Calypso with Me Mardi Gras Masquerade Game of Chance South Sea Samba The Street Musician Turn Back the Time The Portuguese Paper Boy 1958

That Jazbo Dixieland Band [10,12]1961

Tessie the Teaser1963

Rocket Rock1966 (Posth.)

The Mid-Town WaltzHopscotch Turn Me Loose Jamaica Now I'll Never, Never Know Travel On The Moonlight Waltz Bajan Girl

1. w/Louis W. Johnson

2. w/Will Dorsey 3. w/Beth Slater Whitson 4. w/Rose Cohen 5. w/E. Burwell Howard & Erwin Schmidt 6. w/Alonzo A. Govern 7. w/Will R. Williams 8. w/Milton Ager 9. w/Dave Peyton 10. w/Roger Graham 11. w/Walter Hirsch 12. w/May Hill 13. w/Daisy Walton 14. w/Howard Steiner 15. w/J. Russel Robinson 16. w/Olive Prince 17. w/Ollie Debrow 18. w/Marguerite Kendall 19. w/Will E. Skidmore 20. w/Ted Koehler 21. w/Wendell W. Hall 22. w/Clarence Williams 23. w/Maceo Pinkard 24. w/Charley Straight 25. w/Louis Wade 26. w/Anton Lada 27. w/Al Nunez & Joe Cawley 28. w/Johnny Petrone 29. w/James Altiere 30. w/Ray Miller 31. w/Ralph R. Reiche 32. w/Ted Lewis 33. w/Charles F. Harrison 34. w/Mason Pryor 35. w/Babe Thompson 36. w/Irvin C. Miller 37. w/Lucille Hegamin 38. w/Richard Powers & Al Siegel 39. w/Carl Rupp 40. w/Perry Bradford 41. w/Marie E. Savage 42. w/Betty Bowers 43. w/Clarence Johnson 44. w/Edgar Dowell 45. w/Lizzie Miles 46. w/Bob Schafer 47. w/Johnnie Tucker 48. w/Theodore Morse 49. w/Bill Munro & Marcel Klauber 50. w/J. Turner Layton 51. w/Sid Laney 52. w/Donald Heywood 53. as Hannibal Maguire 54. w/Andrea "Andy" Paul Razaf 55. w/Clarence Todd 56. w/Billy Castle 57. w/Thomas "Fats" Waller 58. w/William Grant Still 59. w/Jack Palmer 60. w/Max Kortlander 61. w/Irving Mills 62. w/Bob Ricketts 63. w/Billy Hueston 64. w/Porter Grainger 65. w/Eugene Hunter 66. as Tom Winchester 67. as Duke Jones 68. w/Alex Belledna 69. w/Fay Meisel 70. w/Peter De Rose 71. w/Arthur Ray 72. w/Ted F. Nixon 73. w/Henry Troy 74. w/Tom Morris 75. w/Arthur Bachman, Jr. 76. w/Sidney Bechet 77. w/Maceo Jefferson 78. w/Donald Redman 79. w/Eddie Rector 80. w/Buddy Gilmore 81. w/Joseph M. "Joe" Davis 82. w/Sidney Holden 83. w/Minnie Tiller 84. w/Irving Bibo 85. w/Josephine Baker 86. w/Martha E. Koenig 87. w/W.C. Handy 88. w/Sam Manning 89. w/Adolphe Thenstead 90. w/George E. May 91. w/Gerald Williams 92. w/Diane Lampert 93. w/Horace Lindley 94. w/James P. Johnson 95. w/Agnes Castleton 96. Vs. by Glenn Miller & Jack Teagarden 97. w/Joe Green 98. w/Louis Urquhart 99. w/Eugene Platzman & Larry Spier 100. w/Roy Evans 101. w/Jacques Fray 102. w/Herb Magidson & Michael Cleary 103. w/Ken Macomber 104. w/Charles A. Bayha 105. w/Victoria Spivey 106. w/Howard E. Johnson 107. w/Jack Scholl 108. w/Bradford Browne 109. w/Frank Weldon 110. w/Cliff Burwell 111. w/Eugene Stanley 112. w/Harold R. Mertis 113. w/Chick Smith 114. w/Pierre Goudon 115. w/Obed Pickard 116. w/Pat Castleton 117. w/Glen Powell 118. w/Freddie Taylor 119. w/Herman Chittison 120. w/Jacques Dallin 121. w/Elisco Grenet 122. w/Benny Carter 123. w/Teddy Hill 124. w/Tommie Connor 125. w/Lanny Rogers 126. w/Leo Towers & Ralph Stanley 127. w/Benny Lemarr 128. w/Maurice Burman 129. adapted w/Bob Musel 130. w/Will E. Haines & Monty Richards 131. w/Martin Granger 132. w/Jean Caval 133. w/Jack Simpson 134. w/Sidney Prosen & Charles Reade 135. w/Bob A Davis 136. w/Joe Daniels 137. w/Jack Val & Joe Schuster 138. w/Uana Carlisle 139. w/Harry Gold 140. w/Sid Kessel 141. w/Vincent A. Corso 142. w/Paul Beise 143. w/Lester Holmes 144. w/Django Reinhardt 145. w/Don Marino Barreto 146. w/Don Berry & Desmond O'Connor 147. w/Jean Cavall |

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |

|

1923

Black Man, Be On 'Yo Way [1]1929

Arizona Blues [2]Prairie Blues [2] Utah Mormon Blues [2] Broncho Bustin' Blues [2] It Feels so Good (Parts 1 and 2) [3,4] 1930

The Chicken and the Worm [3,5]It's Sweet Like So [3,5] Pattin' Dat Cat [3,5] The Tampa Twirl [3,5] Goose and Gander [3,5] New Goose and Gander [3,5] Clean It Out [3,5] Blow It Up [3,5]

1. w/Lizzie Miles, vcl

2. w/Phil Pavey, vcl 3. w/James P. Johnson, pno |

Matrix and Recording/Release Date

[Brunswick 10864] 06/??/1923[OKeh 40614] 02/15/1929 [OKeh 40615] 02/15/1929 [OKeh 40616] 02/15/1929 [OKeh 401622/401623] 02/19/1929 [Victor 59738] 04/07/1930 [Victor 59740] 04/07/1930 [Victor 59741] 04/07/1930 [Victor 62178] 06/02/1930 [Victor 62179] 06/02/1930 [Victor 62180] 06/02/1930 [Victor 62181] 06/02/1930

4. w/Lonnie Johnson, vcl

5. w/Teddy Bunn, vcl |

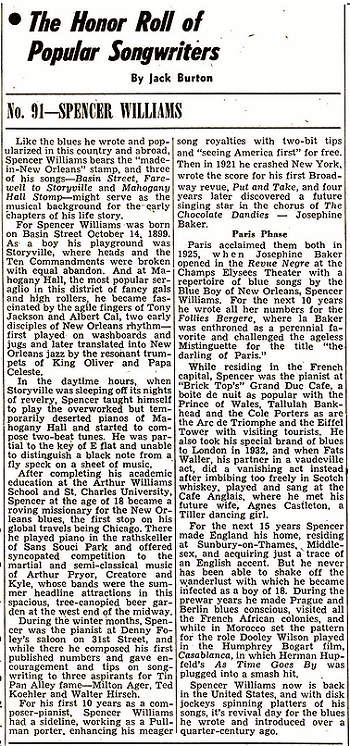

Spencer Williams wrote a great deal of memorable music during his lifetime, but as with many authors, he also spun several tall tales, many of them about his life. Perhaps he did not want to reveal much about his past because of ties with gamblers or criminals that might incriminate him as well, as some have conjectured. Perhaps he did not remember details of his early life, such as was the case with his parents who appear to have not known the date of their own births, both of which were during the time of slavery. It is also possible that he loved the element of mystery as well as his personal privacy, and that only what was in the present mattered to him, not the past. Most accounts of Williams' early years appear to have originated with a Billboard Magazine article from May 5, 1951, with Williams himself providing most of the data. However, given our findings he becomes a less than reliable source on at least some of his own history.

Unlike nearly every other biographical essay in this collection, this particular one needs to be prefaced with some background information concerning the process of locating his actual origins, and to hopefully counter what may be resistance by some to the alterations in Williams' personal story that simply don't match the facts. This author has faced such resistance before, and given the scope of Williams' fan base over time, plus the number of variants involved with other biographies on him, there will possibly be resistance to this one. The author does not wish to diminish Spencer William's story or accomplishments in any way, but rather to put them in a more accurate historical context. So some points of the research will be interjected in his story as to how certain facts were ascertained and how they differ from traditional texts in print and in digital format. The author is also willing to share specifics of his findings and also entertain constructive comments and alternative points of view, but for the moment stands behind this version of Spencer Williams' life as relatively accurate in comparison with most of its predecessors.

Beginnings — True and False

Spencer Williams was born to a prostitute mother in a Basin Street bordello in New Orleans on October 14, 1889… This sounds like a wonderful romantic notion, a musician who was part of the crop that came from the Crescent City of the Deep South, just the way that the ultimate musical patriot George M. Cohan was born on the fourth of July. However, Cohan was actually born on the third of July, and Williams came into the world neither in Louisiana nor in 1889. The foundation for what was found centered on his Social Security application made in May of 1955, on which he claimed the same October 14, 1889, date, and listed his parents as Spencer Williams and Della Henley. Since this is on his own application, and it aligns with an actual couple of those names, it changes his origin story just a bit. So we shall start over.

Spencer Walter Williams, Junior, was born on or around October 14, 1886, to Spencer W. Williams (1848) and Della Amanda Henley (possibly Hendley - 1860), most likely in Selma, Alabama. The elder Spencer, an Alabama native born into slavery, and Della, supposedly a Texas native but possibly from Alabama, had been married in Selma on April 4, 1875, when she was around 15-years-old. There was no evidence that she was ever a prostitute, and certainly not in New Orleans. Spencer later claimed that his father was from Trinidad and his mother was part Polish, but no evidence was found in official ancestral or government records to that effect. They reportedly had a daughter in 1879, although that child was not seen listed with the couple in the 1880 census taken in Selma, where Spencer was listed as working on the railroad. The daughter, who may actually have been born shortly after the 1880 enumeration, died in July of 1883. Given the dearth of available birth records and the lack of an 1890 Federal enumeration, the best clue as to the younger Spencer's true year of birth is contained in the 1900 census, taken in Birmingham, Alabama, 90 miles to the north of Selma. In this enumeration, Spencer, Sr., was shown working as a cook, and Spencer, Jr., was a 13-year-old attending school.

The daughter, who may actually have been born shortly after the 1880 enumeration, died in July of 1883. Given the dearth of available birth records and the lack of an 1890 Federal enumeration, the best clue as to the younger Spencer's true year of birth is contained in the 1900 census, taken in Birmingham, Alabama, 90 miles to the north of Selma. In this enumeration, Spencer, Sr., was shown working as a cook, and Spencer, Jr., was a 13-year-old attending school.

The daughter, who may actually have been born shortly after the 1880 enumeration, died in July of 1883. Given the dearth of available birth records and the lack of an 1890 Federal enumeration, the best clue as to the younger Spencer's true year of birth is contained in the 1900 census, taken in Birmingham, Alabama, 90 miles to the north of Selma. In this enumeration, Spencer, Sr., was shown working as a cook, and Spencer, Jr., was a 13-year-old attending school.

The daughter, who may actually have been born shortly after the 1880 enumeration, died in July of 1883. Given the dearth of available birth records and the lack of an 1890 Federal enumeration, the best clue as to the younger Spencer's true year of birth is contained in the 1900 census, taken in Birmingham, Alabama, 90 miles to the north of Selma. In this enumeration, Spencer, Sr., was shown working as a cook, and Spencer, Jr., was a 13-year-old attending school.In traditional narratives the younger Spencer claimed that he spent much of his childhood in New Orleans, and that his mother died in 1897, leaving him to fend for himself, living for a time with his Aunt Lulu at the famous Lulu White's Mahogany Hall in the notorious Storyville district before moving to Alabama to live with "relatives" during his adolescence. His claim of Della as his mother on his Social Security application coupled with the family living together in Montgomery counters at least some of this story, so doubts can be cast on any extended late-nineteenth century forays into learning how to play music on the streets of NOLA. He may have spent some time there, but was still based in Montgomery. To further reinforce this identity, the 1900 census showed that the Williams had been married for 23 years, which is not far off from the actual 25 they had been together. It also showed that she had given birth to four children, and that two had survived to 1900, the other one being Bessie Williams born two to three years prior to Spencer (and died in March of 1961). That Spencer was listed as 13 when the record was taken on June 6 directly corresponds with an 1886 birth year. On later records he would stretch this truth in both directions. He is known to have spent some time with relations in the small town of Tishomingo in northeast Mississippi and to the west of Montgomery. There is a possibility that Spencer also spent time in New Orleans during the summers of his adolescence. However, it is hard to imagine the circumstances under which most parents might have allowed a young boy to do so in the manner and location he later described, albeit during a much different time in the United States.

Aunt Lulu and Musical Influences

Lulu Henley (some sources cite Hendley) was either Della's younger sister or a close relation of some kind, potentially the elder Spencer's stepdaughter. When Bessie Williams Johnson died in 1961, she listed her mother as Della Amanda White, so the family connection may have been deeper, or it was just a confused memory.

Born in Selma around 1867, Lulu was destined to be one of the more famous women in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century. Fed up with rampant prostitution found throughout that town, which was a favored Naval base and tourist destination, demands were made on the aldermen to control it in some way. Alderman Sidney Story devised a plan that eventually held up to scrutiny even in the Supreme Court. He designated a 16 block boundary around the Tremé area just west of the French Quarter. Without designating it as a legal haven for prostitution, he instead made it illegal to practice prostitution, and even for prostitutes to reside, outside of that boundary, therefore tacitly expressing that what happened in that area stayed in that area. In dubious honor of their legal benefactor, the occupants, or perhaps some indignant "proper" citizens, dubbed it Storyville, an honor that Sidney was not pleased about, but could not undo. Many enterprises, most run by women, quickly sprung up in Storyville, from rows of 6'x8' cribs to luxurious palaces.

|

Lulu, now going by Lulu White, and known since the early 1890s for her nicely appointed brothel, set up one of the most ostentatious houses of ill repute, a four story palace on Basin Street, built at a cost of $40,000. She called it Mahogany Hall, and opened it around 1898 or 1899. Until the district was shut down in 1917 due to Naval interference at the outset of the United States' involvement in World War I, Lulu kept her business running, even in the face of bankruptcies and frequent arrests, as well as occasional sojourns to southern California for rest. Lulu White's Mahogany Hall was both reviled and admired by the citizens of New Orleans, and right across from the train station, a favored destination for sailors and traveling salesman. Her lavishly appointed home, which specialized in octoroons or Creoles of 1/4 to 1/8 Negro heritage—almost white—was also the location for many celebrated parties and fine music.

Jazz, it is said by some, originated in New Orleans, and thrived at Mahogany Hall. In 1908, she built a saloon next door to her mansion, and there featured many great musicians well into the 1920s. It was one of the last standing buildings of the original Storyville, most of which was bulldozed away in the 1940s in a municipal effort to visually eradicate that "shameful" episode of New Orleans' past.

|

Spencer's time there may have begun in his late teens when he left home, seeking new horizons away from Alabama. Seduced by the music and other facets of the Crescent City, by the early years of the century Spencer was soaking in the musical influences and the lifestyle, possibly residing at Aunt Lulu's home. Among those that he tried to emulate at the piano was the highly talented Antonio Junius "Tony" Jackson, an openly gay black performer and composer who would later become known for the tune Pretty Baby. Another name he mentioned later was that of pianist Albert Carrol, also head of the Louisiana Minstrels. (He was cited as Albert Cal in one interview, so that name was likely misheard or misstated.) Spencer undoubtedly heard many other fine talents during this time, including trumpeter Buddy Bolden and many of his friends. He would soak up everything he could about New Orleans and it would later emerge in both his lyrics and music. While he may have been there a few times prior to 1901, the most likely period of time he was largely in that city would be from 1902 to 1907, a period in which he is notably absent from Birmingham directories, with only his father shown, still working as a cook at the Hillman Hotel.

There is a possibility that Spencer was briefly married during this period. On the 1930 census, in which the information may have been given to the enumerator by one of his housemates, it was indicated that he had been married at 22, which given ignoring his reported age of 50 and looking at a more realistic range would have translated to around 1907 to 1909. Given those variables in age, and that no marriages with his name in New Orleans appeared at that time, one possible name emerged, although not an entirely likely candidate. Amy Lamb was married to a Spencer Williams in Birmingham on April 21, 1909, a period of time when the composer was most likely living in Chicago. He was not confirmed to be this particular Spencer Williams,

who may actually have been an ore miner of that name, but this tidbit is included for the purpose of further research.

|

As for his musical education, there was no confirmation that Spencer ever attended a musical college or conservatory. His secondary education was reportedly at the Arthur Williams School (which may have since been renamed or closed). While he named St. Charles University as the source of his book knowledge, the closest matching school that could be found was the University of Louisiana in St. Charles, not New Orleans, so that leaves a question mark as to his actual schooling. This also contradicts his assertion that he had no formal musical training. Much of what he initially learned about playing piano and writing songs may have been from real time life experience. Some of his mentors may have given him lessons here and there, and his natural ability, while not extraordinary, was competent enough for him to progress on his own. He claimed to have worked out several two-beat tunes during the quiet daytime hours at Mahogany Hall, and found he favored the key of E-flat. Based on his publishing history and the progression of his tunes through the 1910s, it appears that some of that education came through trial by fire, learning as he went along what worked and what did not. It could be that he would try something out on one of his peers and they would make suggestions, and after enough of those had been proffered, Spencer was able to work largely on his own and with other composers and lyricists with a measure of confidence. But his initial plunge into music and the lasting influence from it was apparently soaked up both in Birmingham and New Orleans.

After that, during his many travels, he would visit New Orleans whenever he could through the mid-1910s. Once his mother had died in 1915, Lulu lost interest in her enterprises, and local musicians started migrating north to Chicago, New Orleans would perhaps lose some of its luster and appeal for Spencer, except in a nostalgic sense, as was evidenced in his later tunes.

Chicago – from Pullman to Song Man

Williams first arrived in Chicago around 1907 to 1908. Perhaps still dubious about making a living as a musician, he secured a job as a Pullman Porter, a career he said that allowed him to see America while also earning a decent income. However, during breaks from these travels he did play piano, including for the Rathskellar at San Souci Park, a popular summer spot where headliners included popular military bands of the time, such as that of Arthur Pryor. He eventually secured a winter gig at Denny Foley's Saloon on 31st street, the location where he claims he worked out some of his first published numbers. The first one that was located was For You Are My Love in Zululand, published in 1909 in Chicago and arranged by Thomas R. Confare, noted for his treatment of Cannon Ball Rag by Joseph C. Northup.

However, during breaks from these travels he did play piano, including for the Rathskellar at San Souci Park, a popular summer spot where headliners included popular military bands of the time, such as that of Arthur Pryor. He eventually secured a winter gig at Denny Foley's Saloon on 31st street, the location where he claims he worked out some of his first published numbers. The first one that was located was For You Are My Love in Zululand, published in 1909 in Chicago and arranged by Thomas R. Confare, noted for his treatment of Cannon Ball Rag by Joseph C. Northup.

However, during breaks from these travels he did play piano, including for the Rathskellar at San Souci Park, a popular summer spot where headliners included popular military bands of the time, such as that of Arthur Pryor. He eventually secured a winter gig at Denny Foley's Saloon on 31st street, the location where he claims he worked out some of his first published numbers. The first one that was located was For You Are My Love in Zululand, published in 1909 in Chicago and arranged by Thomas R. Confare, noted for his treatment of Cannon Ball Rag by Joseph C. Northup.

However, during breaks from these travels he did play piano, including for the Rathskellar at San Souci Park, a popular summer spot where headliners included popular military bands of the time, such as that of Arthur Pryor. He eventually secured a winter gig at Denny Foley's Saloon on 31st street, the location where he claims he worked out some of his first published numbers. The first one that was located was For You Are My Love in Zululand, published in 1909 in Chicago and arranged by Thomas R. Confare, noted for his treatment of Cannon Ball Rag by Joseph C. Northup.It was two more years before Spencer's next credited compositions, including one that would seem unlikely to many, but came about in a logical way. Beth Slater Whitson was a Tennessee poet who had ventured to Chicago a few years prior trying to sell her poems as lyrics, having not hit the mark as a composer. A couple of publishers took in her work and teamed her up with composers they knew. With Leo Friedman she hit the jackpot with the hit song Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland in 1909. The following year the pair improved on that success with Let Me Call You Sweetheart. Beth would send in her lyrics to Chicago and New York publishers from her home, and with her newly found success, they would distribute them to composers to turn into a song. Such was the luck of Williams, who had potentially been shopping either his talent or his music to Chicago publishers. Will Rossiter gave him this chance, and while It Is You That I Love To-Day did not result in a stellar hit, it did establish him with Rossiter as a capable composer, setting the stage for his growth. A few other works were self-copyrighted by Williams and self-published in small batches by either himself or his co-composers.

One tune from 1912 evidently had three variants in its title or lyrics. Originally titled Baby, Please Don't Shake Me While I'm Gone to lyrics by a Rose Cohen (probably a white woman as no blacks by that name were located in Chicago or surrounding areas), it was later re-copyrighted by Williams with the variants Shake It and Trifle, indicating the possibility that it had been recorded, and perhaps published in more than one edition by Harold Rossiter (not his brother Will Rossiter as some sources show). This combination likely came together in the same way his Whitson collaboration had. While it got a little bit of traction in Chicago, little else did over the next three years, and his primary income was still from occasional gigs and the tips he received for his Pullman job. However, one tune, albeit of questionable origin or authorship, changed everything for Spencer in 1915, but it came with a story that even a century later is not fully resolved.

it was later re-copyrighted by Williams with the variants Shake It and Trifle, indicating the possibility that it had been recorded, and perhaps published in more than one edition by Harold Rossiter (not his brother Will Rossiter as some sources show). This combination likely came together in the same way his Whitson collaboration had. While it got a little bit of traction in Chicago, little else did over the next three years, and his primary income was still from occasional gigs and the tips he received for his Pullman job. However, one tune, albeit of questionable origin or authorship, changed everything for Spencer in 1915, but it came with a story that even a century later is not fully resolved.

it was later re-copyrighted by Williams with the variants Shake It and Trifle, indicating the possibility that it had been recorded, and perhaps published in more than one edition by Harold Rossiter (not his brother Will Rossiter as some sources show). This combination likely came together in the same way his Whitson collaboration had. While it got a little bit of traction in Chicago, little else did over the next three years, and his primary income was still from occasional gigs and the tips he received for his Pullman job. However, one tune, albeit of questionable origin or authorship, changed everything for Spencer in 1915, but it came with a story that even a century later is not fully resolved.

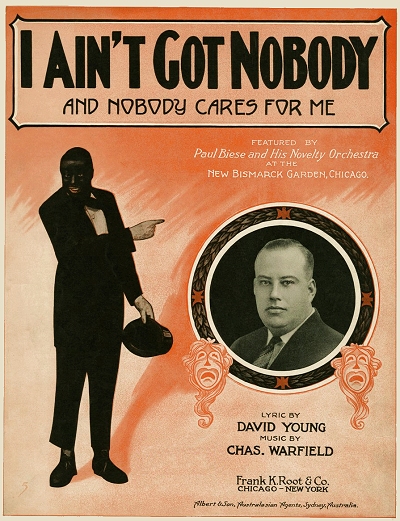

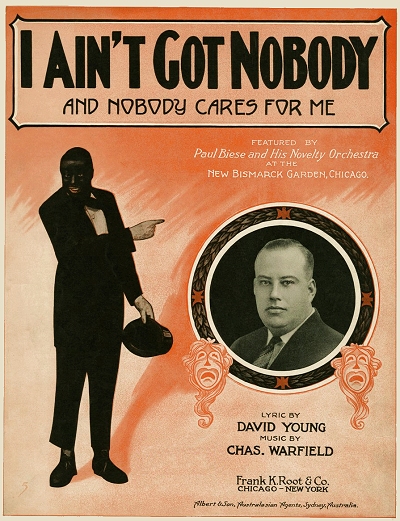

it was later re-copyrighted by Williams with the variants Shake It and Trifle, indicating the possibility that it had been recorded, and perhaps published in more than one edition by Harold Rossiter (not his brother Will Rossiter as some sources show). This combination likely came together in the same way his Whitson collaboration had. While it got a little bit of traction in Chicago, little else did over the next three years, and his primary income was still from occasional gigs and the tips he received for his Pullman job. However, one tune, albeit of questionable origin or authorship, changed everything for Spencer in 1915, but it came with a story that even a century later is not fully resolved.Chances are excellent that I Ain't Got Nobody started out as a regional folk strain of some kind that simply had not been yet notated, but was at least somewhat known. The first claim to the song went to rag composers Clarence E. Brandon, Sr., and Billy Smythe of St. Louis, Missouri, who copyrighted and self-published a version of the strain in 1911. It may not have traveled too far from St. Louis in sheet music form. In 1914, another ragtime pianist and singer, Charles Warfield, along with lyricist David Young, claimed to have composed the tune as well, copyrighting I Ain't Got Nobody and Nobody Cares for Me in New York on April 8, 1914 with an arrangement by Marie Lucas. The copyright was curiously claimed for the melody only. Then Spencer "discovered" this floating strain and did his own take on it. His initial copyright was for a slightly different work titled I Ain't Got Nobody Much on January 28, 1915, with a claim to lyrics by Dave Peyton. This, in turn, was lyrically re-worked by publisher Roger Graham, enough that he felt he deserved credit for the new version. This take on I Ain't Got Nobody was copyrighted on February 7, 1916, and claimed Peyton now as a co-writer of the music by Williams instead of the lyrics, which were attributed to Graham.

To provide some perspective, while there may have been enough similarity beyond the titles to at least get a case into court for plagiarism, that Williams and his co-writers independently used similar source material to Warfield's and probably Brandon's, plus some mildly substantive differences in lyrics, syncopations, rhythms and some of the melodic line, it might have been determined to let the pieces duel it out based on their own merit. Williams was known for being an original, and when he did rework older material in subsequent years, proper attributions were made. Publisher Frank Root acquired both the Williams and Warfield versions of the piece in the spring of 1916, then published them and let the performers decide which one they wanted to move forward with. The Williams/Peyton/Graham version quickly won favor, and the initial 1916 recording by Marion Harris turned it into a hit that has remained in the American songbook for over a century. We may never be fully certain of who originated it, but Williams was certainly the most successful of those who transformed the strain into a popular tune.

plus some mildly substantive differences in lyrics, syncopations, rhythms and some of the melodic line, it might have been determined to let the pieces duel it out based on their own merit. Williams was known for being an original, and when he did rework older material in subsequent years, proper attributions were made. Publisher Frank Root acquired both the Williams and Warfield versions of the piece in the spring of 1916, then published them and let the performers decide which one they wanted to move forward with. The Williams/Peyton/Graham version quickly won favor, and the initial 1916 recording by Marion Harris turned it into a hit that has remained in the American songbook for over a century. We may never be fully certain of who originated it, but Williams was certainly the most successful of those who transformed the strain into a popular tune.

plus some mildly substantive differences in lyrics, syncopations, rhythms and some of the melodic line, it might have been determined to let the pieces duel it out based on their own merit. Williams was known for being an original, and when he did rework older material in subsequent years, proper attributions were made. Publisher Frank Root acquired both the Williams and Warfield versions of the piece in the spring of 1916, then published them and let the performers decide which one they wanted to move forward with. The Williams/Peyton/Graham version quickly won favor, and the initial 1916 recording by Marion Harris turned it into a hit that has remained in the American songbook for over a century. We may never be fully certain of who originated it, but Williams was certainly the most successful of those who transformed the strain into a popular tune.

plus some mildly substantive differences in lyrics, syncopations, rhythms and some of the melodic line, it might have been determined to let the pieces duel it out based on their own merit. Williams was known for being an original, and when he did rework older material in subsequent years, proper attributions were made. Publisher Frank Root acquired both the Williams and Warfield versions of the piece in the spring of 1916, then published them and let the performers decide which one they wanted to move forward with. The Williams/Peyton/Graham version quickly won favor, and the initial 1916 recording by Marion Harris turned it into a hit that has remained in the American songbook for over a century. We may never be fully certain of who originated it, but Williams was certainly the most successful of those who transformed the strain into a popular tune.Now that he had a bit more to call on in terms of his ability, Spencer slowly moved more toward songwriting as a career, more so than performance. He also later claimed to have helped give important songwriting tips to three of his co-composers who became notable in their own right, Milton Ager, Ted Koehler, and Walter Hirsch, although this was more likely a small boast or exaggeration. His next big hit was Tishomingo Blues in 1917, recalling the days of his youth in that town. While it was a steady seller, bandleader Duke Ellington would ensure its place as a standard with his 1928 recording of the piece. Folksy radio star Garrison Keillor would further embed the melody into the hearts of millions by using it with altered lyrics for the main theme of his long-running show A Prairie Home Companion, which ended its four-decade run in 2016 when the song was 99 years old. Other tunes such as The Cocaine Dance or Steppin' on the Puppy's Tail were more novelties than substantive, but still were sold and sometimes recorded. In 1918 Spencer nearly doubled his prior year's output, putting out over a dozen tunes, some to his own lyrics. However, he was evidently still not so sure about the stability of songwriting as a living, since on his last call September 12, 1918, draft record, he listed his living as still working for Pullman as a Porter on the rails. He also pushed his age a bit, claiming an 1884 birth year, perhaps an attempt to make him too old to be a viable asset to the United States Army, particularly with the "2 broken knees" that he claimed as a reason for exemption.

He also pushed his age a bit, claiming an 1884 birth year, perhaps an attempt to make him too old to be a viable asset to the United States Army, particularly with the "2 broken knees" that he claimed as a reason for exemption.

He also pushed his age a bit, claiming an 1884 birth year, perhaps an attempt to make him too old to be a viable asset to the United States Army, particularly with the "2 broken knees" that he claimed as a reason for exemption.

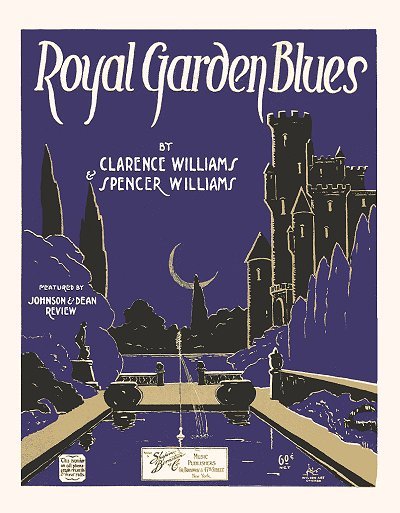

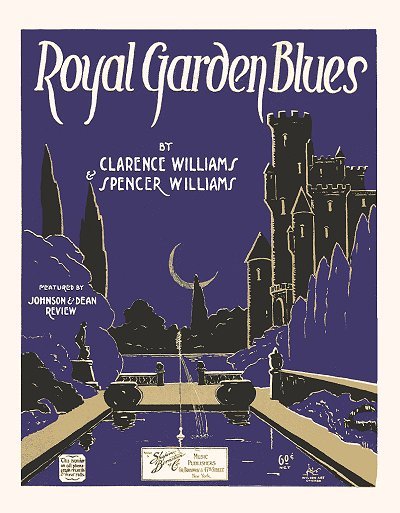

He also pushed his age a bit, claiming an 1884 birth year, perhaps an attempt to make him too old to be a viable asset to the United States Army, particularly with the "2 broken knees" that he claimed as a reason for exemption.Spencer would meet another like-minded individual in 1919 that would set him on a path that veered away from Pullman cars and piano dives. Clarence Williams (with the usual disclaimer - no known relation) had worked a bit in vaudeville in the South, particularly in Texas and Louisiana. Unlike Spencer, he was actually born just outside of New Orelans, and spent quite a bit of time there in the mid-1910s. During that period he learned the efficacy of gaining control over one's own product, and started a publishing house with Armand J. Piron. Just after the end of the war in early 1919, Clarence followed the general flow of traffic of musicians from New Orleans north to Chicago, opening a branch of Williams & Piron there. By the middle of the year he had connected with Spencer, and was looking to eventually create a new publishing house with a high quality catalog that focused on people of color. Relatively soon the two Southerners started to collaborate on a number of works. Of those, Royal Garden Blues was clearly their earliest success. It was written to celebrate a Chicago venue, the Royal Gardens Café, which featured some of the finest jazz bands in the country, including Joseph "King" Oliver's Creole Jazz Band. In reality, the piano score of Royal Garden Blues does not match the vivacity and ferocity that a good jazz band was able to infuse into it. The repetitive trio worked better with changes in timbre on each iteration, a little improvisation, and varying textures of the instruments. The lyrics did not work well at all, and were included largely to sell sheet music. In spite of that, Royal Garden Blues almost instantly became a Chicago jazz, then later a Dixieland jazz standard, and remains as such a century later. (The Royal Gardens were later renamed the less romantic Lincoln Gardens.)

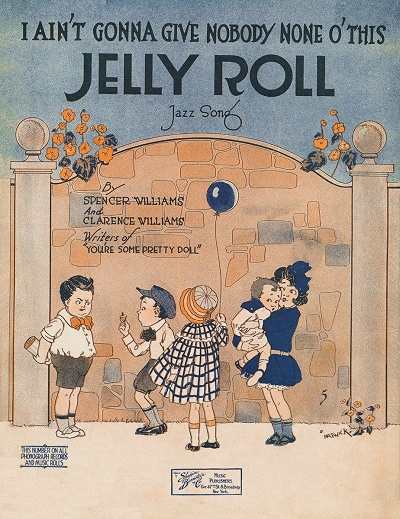

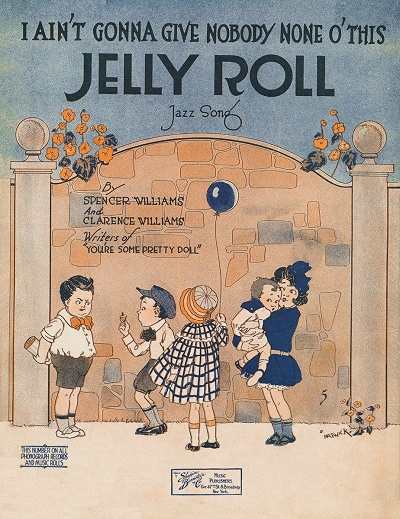

But that was hardly their only bit of musical magic that year. Another piece built around what was pretty much a popular sexual slang term also became a hit. I Ain't Goin' to Give You None o' This Jelly Roll also became another jazz standard in a short time, and it had a vocal that was easier to pull off than that of Royal Garden Blues. It managed to combine some of the authentic feel of New Orleans with the more urban sound of Chicago. The innocent looking Grim Natwick cover didn't exactly cover up the intended topic for those who knew better. To add to what was a trifecta, they came forth with Yama Yama Blues which was quickly committed to shellac for consumption by phonographs everywhere. To sweeten up the deal, Clarence, who was a very effective if somewhat forceful salesman, sold the copyrights of these three works and a few others to Shapiro, Bernstein & Company in New York, and managed a royalty clause in the transaction, assuring an income stream for both of the Williams. Some of the deal was announced in the Music Trade Review of July 12, 1919:

It managed to combine some of the authentic feel of New Orleans with the more urban sound of Chicago. The innocent looking Grim Natwick cover didn't exactly cover up the intended topic for those who knew better. To add to what was a trifecta, they came forth with Yama Yama Blues which was quickly committed to shellac for consumption by phonographs everywhere. To sweeten up the deal, Clarence, who was a very effective if somewhat forceful salesman, sold the copyrights of these three works and a few others to Shapiro, Bernstein & Company in New York, and managed a royalty clause in the transaction, assuring an income stream for both of the Williams. Some of the deal was announced in the Music Trade Review of July 12, 1919:

It managed to combine some of the authentic feel of New Orleans with the more urban sound of Chicago. The innocent looking Grim Natwick cover didn't exactly cover up the intended topic for those who knew better. To add to what was a trifecta, they came forth with Yama Yama Blues which was quickly committed to shellac for consumption by phonographs everywhere. To sweeten up the deal, Clarence, who was a very effective if somewhat forceful salesman, sold the copyrights of these three works and a few others to Shapiro, Bernstein & Company in New York, and managed a royalty clause in the transaction, assuring an income stream for both of the Williams. Some of the deal was announced in the Music Trade Review of July 12, 1919:

It managed to combine some of the authentic feel of New Orleans with the more urban sound of Chicago. The innocent looking Grim Natwick cover didn't exactly cover up the intended topic for those who knew better. To add to what was a trifecta, they came forth with Yama Yama Blues which was quickly committed to shellac for consumption by phonographs everywhere. To sweeten up the deal, Clarence, who was a very effective if somewhat forceful salesman, sold the copyrights of these three works and a few others to Shapiro, Bernstein & Company in New York, and managed a royalty clause in the transaction, assuring an income stream for both of the Williams. Some of the deal was announced in the Music Trade Review of July 12, 1919:Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc., have made arrangements to publish the songs of Spencer Williams, a composer who has had much success during the past season. Shortly to be released are "Yama Yama Blues," "Trix Ain't Walking No More" and "I Ain't Gonna Give This Jelly Roll." [sic]

This was followed by a similar hype from Clarence in the September 6, 1919, edition of the Music Trades:

Williams & Piron, music publishers of Chicago, have just put out three new numbers, all of which promise to find big favor. Two of them are by Clarence Williams, head of the company, who is one of the best-known composers of "jazz" and "blues" music in the country. … The three new numbers are "Royal Garden Blues," by Clarence Williams and Spencer Williams, who is also widely known as a composer; "Who Made You Cry, Sugar Baby?" by Clarence and Spencer Williams; "Don't Tell Your Monkey Man," by Lukie Johnson and Ted Koehler. … "The demand for jazz music never was so great as it is right now," Mr. Williams said to THE MUSIC TRADES. "All our numbers are going well but we predict a record sale for our three new numbers, judging from the avalanche of orders received already. The people want good jazz music and that is what we aim to give all the time."

This continuing good fortune convinced Spencer to finally quit riding the rails as a porter, and he became a full-time songwriter, as well as a part-time accompanist and performer. As for Clarence, he would make his way to New York in 1920 to start another publishing house with his new financial gains. Spencer remained in Chicago throughout 1920, and managed to produce a variety of tunes that were soon issued by local publishers. However, none of them were hits of any particular merit. In a later interview for Ebony in 1954, Williams claimed he had been married around this time to blues singer Lizzie Smith, but did not indicate whether that was in Chicago or New York. No official record of this union during the prescribed time period of 1920 to 1923 was located, so it remains unclear if they were actually married, or were simply cohabitating. In any event, their union did not last terribly long. During this period, Clarence was likely still in communication with Spencer, and now that he was becoming established in New York City as a viable publishing house, he may have been one of the major factors that finally tipped Spencer over the edge, propelling him away from Chicago and into the heart of Tin Pan Alley. His first year in New York in 1921 would be an eventful one, but the overall decade of the 1920s would challenge Spencer immeasurably.

New York and New Horizons

When Spencer Williams arrived in New York City in the winter of 1921, he was already known to the musical world there, and was warmly greeted. Clarence had, in a sense, already paved the way, and in that Clarence Williams manner had already more or less implicated himself into the lives of many great black artists, including James P. Johnson, Perry Bradford, Willie "The Lion" Smith, and 17-year-old rising star Thomas "Fats" Waller. So Spencer had some built in connections. He also had some new songwriting partners, including one he had already been writing with long-distance for some months, Anton Lada. They would make a splash at the end of the year. However, one of the first assignments handed to Spencer was to contribute to the upcoming Irvin C. Miller revue, Put and Take (originally Chocolate Brown). Along with Bradford and lyricist J. Tim Brymn, Spencer's numbers helped to make a lively and well-reviewed revue, as stated in the New York World on August 24, 1921:

He also had some new songwriting partners, including one he had already been writing with long-distance for some months, Anton Lada. They would make a splash at the end of the year. However, one of the first assignments handed to Spencer was to contribute to the upcoming Irvin C. Miller revue, Put and Take (originally Chocolate Brown). Along with Bradford and lyricist J. Tim Brymn, Spencer's numbers helped to make a lively and well-reviewed revue, as stated in the New York World on August 24, 1921:

He also had some new songwriting partners, including one he had already been writing with long-distance for some months, Anton Lada. They would make a splash at the end of the year. However, one of the first assignments handed to Spencer was to contribute to the upcoming Irvin C. Miller revue, Put and Take (originally Chocolate Brown). Along with Bradford and lyricist J. Tim Brymn, Spencer's numbers helped to make a lively and well-reviewed revue, as stated in the New York World on August 24, 1921:

He also had some new songwriting partners, including one he had already been writing with long-distance for some months, Anton Lada. They would make a splash at the end of the year. However, one of the first assignments handed to Spencer was to contribute to the upcoming Irvin C. Miller revue, Put and Take (originally Chocolate Brown). Along with Bradford and lyricist J. Tim Brymn, Spencer's numbers helped to make a lively and well-reviewed revue, as stated in the New York World on August 24, 1921:Every spin is a Take All and seeps in the amusement pots in "Put and Take," the colorful (the pun is the programme's) musical comedy that opened last night at the Town Hall. Jazz, ragtime, funmaking and dancing make up an entertainment that is even more fascinating than the game for which the show is named.

This company of negro [sic] artists works energetically and tirelessly to please. Its members' pep is boundless. They appear to be willing to do anything short of breaking their necks to make the audience like them. They succeeded unmistakably last night. With it all the performers appear to enjoy their own antics so thoroughly that the pleasure could not help being contagious. Every feature was encored repeatedly…

The music was written by Spencer Williams and includes every variety of blues and jazz numbers that are likely to be popular hits.

On Brymn's role as the conductor interpreting Williams' fine tunes, the New York Tribune of the same date added:

… This revue is credited to Irvin C. Miller, the music being written by Spencer Williams, Perry Bradford and Tim [Brymn]. Tim [Brymn], who alternately coaxed and threatened the orchestra from the leader's box, was one of the interesting figures in Jim Europe's band.

In spite of how well it was doing, or perhaps because of how well a black-run show was doing in a still largely white field, and despite continued sold out crowds, the show was pulled in less than a month, reportedly due to racial pressures more so than financial ones. However, within a couple of weeks of that, at the end of a year that saw an increasing number of interesting tunes, both solo from Spencer and with other writers, came the Williams and Lada composition Arkansas Blues. Introduced by singer Lucille Hegamin, who would also become a contributor to Spencer's song catalog, she took second place at a blues singing contest held at the Manhattan Casino that had a large white audience in attendance, giving Williams great exposure. Under the right hands, including Lada with his Louisiana Five, it was a hard-driving almost boogie blues number that instantly took hold. The Music Trade Review of December 24, 1921, stated that:

giving Williams great exposure. Under the right hands, including Lada with his Louisiana Five, it was a hard-driving almost boogie blues number that instantly took hold. The Music Trade Review of December 24, 1921, stated that:

giving Williams great exposure. Under the right hands, including Lada with his Louisiana Five, it was a hard-driving almost boogie blues number that instantly took hold. The Music Trade Review of December 24, 1921, stated that:

giving Williams great exposure. Under the right hands, including Lada with his Louisiana Five, it was a hard-driving almost boogie blues number that instantly took hold. The Music Trade Review of December 24, 1921, stated that:"Arkansas Blues," described as a down-home chant, and which is published by the Frances Clifford Music Co., Chicago, Ill., is fast establishing a record for a number of its type. For a period of months it has been one of the most successful of the novelty song and instrumental numbers. Generally speaking, the life of a "blues" number is quite short, but such is not the case with "Arkansas Blues." It is apparently easy to sing and as it is featured extensively in theatres, cabarets, dance halls, amusement parks, etc., its sales should be quite large during the present season. The writer of the number, Spencer Williams, in describing it, said: "The melody of 'Arkansas Blues' is similar to the chant of the Voodoo doctors at a time when they are indulging in their witchcraft dances." …

It is interesting to note that Spencer, who by now was an early black member of ASCAP, was still showing some allegiance to the Chicago publishers who had been there for him. Even Clarence, who was building up his soon-to-be-dominant in the black music world Clarence William Music Publishing Company (CWMPC) was getting scant material from his sometimes partner. Spencer would soon enough refer his compositions to a number of New York concerns as well.

While 1922 saw no real hits from Clarence, it did include some charming tunes, and quite a few were recorded in short order either to disc or piano roll. While two of them were substantive blues pieces, West Indies Blues and Achin' Hearted Blues, co-composed in part with Clarence, it should be noted (and is discussed in more detail in Clarence Williams' upcoming biographical essay) that the "other" Williams often implied himself onto tunes. In other words, when he was the publisher he was known to somehow get his name into the copyright and even on to the cover even when his contribution was negligible, if any. This was not an uncommon practice in the entertainment world, with even singers implicating their names into pieces. However, Clarence, as a black publisher lending a helping hand to his peers, had a bit more sway in how things were done. While it appears that Spencer did not quite kowtow to his younger peer, some black composers would do whatever it took to get published and receive a taste of the consumer's dollars. Yet Clarence was rarely called out as a bully in this regard, and while many other publishers, mostly white, had to retain permanent legal counsel due to ongoing lawsuits about royalties, rights or plagiarism, it is hard to find such actions taken against Clarence Williams, who was certainly collecting a bounty in royalty returns. So his role was certainly well regarded, or at least guarded. The two Williams seemed to get along relatively well during the 1920s.

However, Clarence, as a black publisher lending a helping hand to his peers, had a bit more sway in how things were done. While it appears that Spencer did not quite kowtow to his younger peer, some black composers would do whatever it took to get published and receive a taste of the consumer's dollars. Yet Clarence was rarely called out as a bully in this regard, and while many other publishers, mostly white, had to retain permanent legal counsel due to ongoing lawsuits about royalties, rights or plagiarism, it is hard to find such actions taken against Clarence Williams, who was certainly collecting a bounty in royalty returns. So his role was certainly well regarded, or at least guarded. The two Williams seemed to get along relatively well during the 1920s.

However, Clarence, as a black publisher lending a helping hand to his peers, had a bit more sway in how things were done. While it appears that Spencer did not quite kowtow to his younger peer, some black composers would do whatever it took to get published and receive a taste of the consumer's dollars. Yet Clarence was rarely called out as a bully in this regard, and while many other publishers, mostly white, had to retain permanent legal counsel due to ongoing lawsuits about royalties, rights or plagiarism, it is hard to find such actions taken against Clarence Williams, who was certainly collecting a bounty in royalty returns. So his role was certainly well regarded, or at least guarded. The two Williams seemed to get along relatively well during the 1920s.

However, Clarence, as a black publisher lending a helping hand to his peers, had a bit more sway in how things were done. While it appears that Spencer did not quite kowtow to his younger peer, some black composers would do whatever it took to get published and receive a taste of the consumer's dollars. Yet Clarence was rarely called out as a bully in this regard, and while many other publishers, mostly white, had to retain permanent legal counsel due to ongoing lawsuits about royalties, rights or plagiarism, it is hard to find such actions taken against Clarence Williams, who was certainly collecting a bounty in royalty returns. So his role was certainly well regarded, or at least guarded. The two Williams seemed to get along relatively well during the 1920s.Trouble came knocking in the fall, as reported in The [New York] Morning Telegraph of September 9, 1922 and other papers. Earlier in the year, composer Lemuel Fowler wrote He May Be Your Man, But He Comes to See Me Sometimes, a moderate hit that had been included in the 1922 show Plantation Revue. When the tune hit the streets it was under the imprint of Perry Bradford's own publishing company. However, Fowler had entered into a written agreement in early 1922 with the Francis Clifford Music Company in Chicago, now under the umbrella of publisher Ted Browne. He brought a suit against Fowler and Bradford for breach of contract, something that probably would not have happened had the song not been so popular with the public. It claimed that while Browne's companies were incorporated, Bradford's was not, and he had no legal rights to collect revenue for the number. However, Bradford claimed that a contract with him had been signed in Chicago on February 9, 1921, a year prior, and supposedly just prior to Spencer's departure for New York. To that end, he took the stand and claimed to have been at the Vincennes Hotel, having also signed the document as a witness. When he was challenged by the prosecution with proof that he had actually been in New York for a few weeks during that time, and could not have possibly signed it, Spencer suddenly denied his role in the whole affair, which was made worse when it was determined the ink was only a month old, not 18 months as it should have been.

The end result was that Fowler, Bradford and Williams were sent to "The Tombs" or the underground downtown jail to think about things for a day or two. Spencer was not there long, and soon back on the street since his role was determined to be minimal. Bradford was in the most trouble, and in January of 1923 was found guilty of not only the breach, more for the subornation of perjury he had perpetrated from Williams and Fowler through some level of coercement. In fact, they acted as government witnesses in Fowler's perjury trial, earning immunity in the process. It was still a pretty close call, and to some degree appears to have given Spencer some material to write about, as his quantity of pieces appended with "Blues" started increasing exponentially in 1923.

and in January of 1923 was found guilty of not only the breach, more for the subornation of perjury he had perpetrated from Williams and Fowler through some level of coercement. In fact, they acted as government witnesses in Fowler's perjury trial, earning immunity in the process. It was still a pretty close call, and to some degree appears to have given Spencer some material to write about, as his quantity of pieces appended with "Blues" started increasing exponentially in 1923.

and in January of 1923 was found guilty of not only the breach, more for the subornation of perjury he had perpetrated from Williams and Fowler through some level of coercement. In fact, they acted as government witnesses in Fowler's perjury trial, earning immunity in the process. It was still a pretty close call, and to some degree appears to have given Spencer some material to write about, as his quantity of pieces appended with "Blues" started increasing exponentially in 1923.

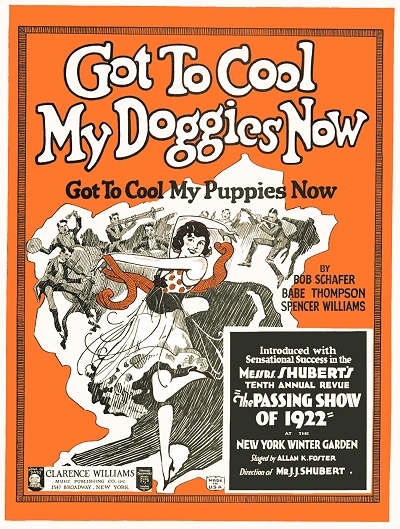

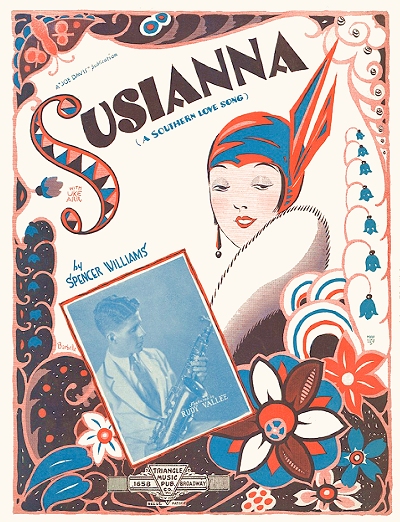

and in January of 1923 was found guilty of not only the breach, more for the subornation of perjury he had perpetrated from Williams and Fowler through some level of coercement. In fact, they acted as government witnesses in Fowler's perjury trial, earning immunity in the process. It was still a pretty close call, and to some degree appears to have given Spencer some material to write about, as his quantity of pieces appended with "Blues" started increasing exponentially in 1923.It was another interesting 1922 piece, originally titled Got to Cool My Puppies Now, but soon more widely known as Got to Cool My Doggies Now, that presented a mutual opportunity for both Spencer and Thomas "Fats" Waller. It had been included in the Shubert's annual Passing Show of 1922, and within a few months it became one of the first piano rolls cut by Waller, along with a few other choice Williams numbers from the same year, including Snakes' Hips and Haitian Blues. Waller's exemplary interpretations rife with musical humor, held tenths and clever fills won him an instant friend and collaborator, and they would continue a fruitful and warm relationship through the end of Fats' all-too-short life. The 18-year-old, who had largely been an organist to that time, was able to carve out a niche with his unique piano roll stylings, and later into a dynamic recording and radio career, often with Spencer right there with him.

Possibly buoyed by his own success as well as that of Clarence Williams, and perhaps looking for a slightly bigger piece of the pie because most of his material was sold outright rather than tied to royalties, in 1923 Spencer briefly opened his own publishing concern. Among those signing the charter was QRS Piano Roll company chief Max Kortlander. Given that he would likely have dibs on any new tune that Spencer published, this was a sound investment. However, judging by the number of other publishers, primarily CWMPC, that were still issuing Spencer's work, this was most likely just a holding company that facilitated the copyrights and negotiated sales of his work and his friends and co-writers. Otherwise, he really started to dig in with more blues and mild novelties, and some of his work found its way onto stages around the country, as well as folios of blues and popular music.

Otherwise, he really started to dig in with more blues and mild novelties, and some of his work found its way onto stages around the country, as well as folios of blues and popular music.

Otherwise, he really started to dig in with more blues and mild novelties, and some of his work found its way onto stages around the country, as well as folios of blues and popular music.

Otherwise, he really started to dig in with more blues and mild novelties, and some of his work found its way onto stages around the country, as well as folios of blues and popular music.By the time 1924 came about, Spencer was in good stead with both white and black members of the musical community in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, and elsewhere. In addition to padding his catalog with blues of every kind, such as Chain Gang Blues, Poor House Blues, Tombstone Blues, Western Union Blues, and many more, he then sat down with Waller and went even deeper into the world of blues by composing pieces that may never have been published, but were at least copyrighted and probably performed. These included Bloody Razor Blues, Bullet Wound Blues, and Ramblin' Papa Blues. One of the most whimsical titles they came up was Flat Tire Papa, Mama's Gonna Give You Air, a phrase which undoubtedly raised eyebrows and conjured up a number of highly suggestive images.

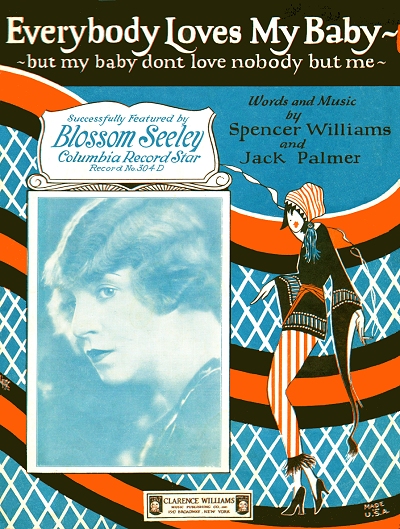

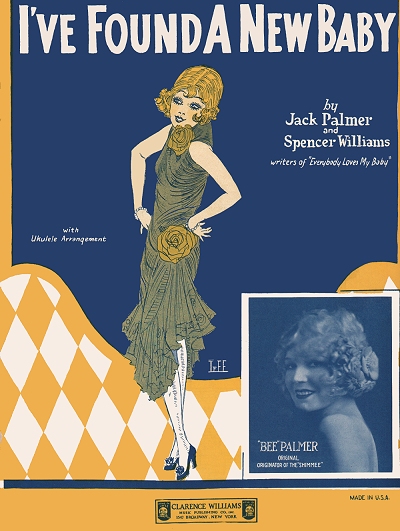

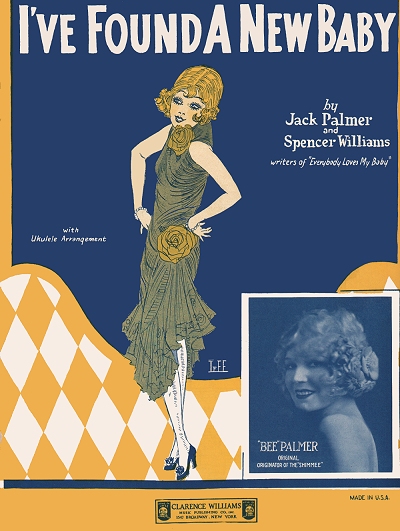

However, one of the most fortuitous pairings of that year, both for Spencer and the jazz and popular music world, was with lyricist Jack Palmer. They only copyrighted two songs that year, but the second one, Everybody Loves My Baby (But My Baby Loves Nobody But Me) took off in a hurry, and has been a popular hot piano and jazz number ever since its debut. The graceful verse led into a sexy yet simple minor chorus with a descending counter line that seduced most listeners from the start. Recordings and piano rolls were in the works almost as it was released in sheet music form, and it even made it into the Ziegfeld Follies for the fall season. Those who recorded it before 1924 was out included singers Trixie Smith Alberta Hunter and Eva Taylor, and the bands of Clarence Williams and another admirer and friend to Spencer, Fletcher Henderson (with Louis Armstrong in the group). It was another fine song that transcended the color lines, unlike many of his deeper blues. If Williams had not fully arrived by this time as one of the batch of top songwriters in the country, this song surely placed him in that field.

Other Spencer Williams tunes saw some great debuts, again in 1924, not the least of them a batch by Louis Armstrong, again with Henderson's orchestra. In fact, Fletcher was one of the best possible advocates in the studios for Spencer, taking his songs to singers that he accompanied, including Ethel Waters and the incomparable Bessie Smith. Over the next year, Henderson, either alone or with an ensemble, would enlighten the public to Spencer's talents as a lyricist and/or composer through the voices of George Williams with Bessie Brown, Rosa Henderson, Clara Smith, Maggie Jones, and Hazel Meyers. If not for color barriers that created issues for many black artists, there would have been much more radio play as well in the big markets. But their recordings on so-called "race" labels like OKeh, Vocalion, Emerson and Paramount kept phonographs busy throughout the country. Among those starting to issue his tunes was another staunch ally, Joe Davis, with whom he would have an ongoing relationship as both a publisher and co-writer for at least two decades.

If not for color barriers that created issues for many black artists, there would have been much more radio play as well in the big markets. But their recordings on so-called "race" labels like OKeh, Vocalion, Emerson and Paramount kept phonographs busy throughout the country. Among those starting to issue his tunes was another staunch ally, Joe Davis, with whom he would have an ongoing relationship as both a publisher and co-writer for at least two decades.

If not for color barriers that created issues for many black artists, there would have been much more radio play as well in the big markets. But their recordings on so-called "race" labels like OKeh, Vocalion, Emerson and Paramount kept phonographs busy throughout the country. Among those starting to issue his tunes was another staunch ally, Joe Davis, with whom he would have an ongoing relationship as both a publisher and co-writer for at least two decades.