Thomas Allen was a somewhat silent but solid staple of the ragtime era, producing a large if not quite extraordinary body of work that did fairly well for his publishers, with some pieces that are still performed more than a century later. He was also a part of the music scene in what was, by 1900, the third largest music publishing center in the United States (formerly the first), behind New York City, New York, and Chicago, Illinois, that of Boston, Massachusetts. Some interesting and long-buried information on his career surfaced during the research, and some is presented here for the first time in over a century.

Thomas Allen was born at the end of the United States centennial year of 1876 in the Boston suburb of Natick, Massachusetts, to Irish immigrants Daniel D. Allen and Johanna Donaher (possibly Doniher). Daniel had fought in a Massachusetts regiment during the American Civil War. Thomas was the youngest of nine siblings, including George (1854), Francis J. "Frank" (6/5/1858), Daniel D., Jr. (1860), John H. (1862), all with Daniel's first wife Catherine, followed by Catherine "Kate" (11/1/1864), twins James Michael and William Patrick (8/6/1866), and George (1874) with his second wife Johanna. The 1870 and 1880 enumerations indicated that Daniel was employed in a Natick shoe factory, and in 1880 further noted that he had some lung trouble, possibly the early stages of tuberculosis, which was unfortunately common at that time. He would die in 1893, leaving Johanna as a widow with two teenagers, George and Thomas.

including George (1854), Francis J. "Frank" (6/5/1858), Daniel D., Jr. (1860), John H. (1862), all with Daniel's first wife Catherine, followed by Catherine "Kate" (11/1/1864), twins James Michael and William Patrick (8/6/1866), and George (1874) with his second wife Johanna. The 1870 and 1880 enumerations indicated that Daniel was employed in a Natick shoe factory, and in 1880 further noted that he had some lung trouble, possibly the early stages of tuberculosis, which was unfortunately common at that time. He would die in 1893, leaving Johanna as a widow with two teenagers, George and Thomas.

including George (1854), Francis J. "Frank" (6/5/1858), Daniel D., Jr. (1860), John H. (1862), all with Daniel's first wife Catherine, followed by Catherine "Kate" (11/1/1864), twins James Michael and William Patrick (8/6/1866), and George (1874) with his second wife Johanna. The 1870 and 1880 enumerations indicated that Daniel was employed in a Natick shoe factory, and in 1880 further noted that he had some lung trouble, possibly the early stages of tuberculosis, which was unfortunately common at that time. He would die in 1893, leaving Johanna as a widow with two teenagers, George and Thomas.

including George (1854), Francis J. "Frank" (6/5/1858), Daniel D., Jr. (1860), John H. (1862), all with Daniel's first wife Catherine, followed by Catherine "Kate" (11/1/1864), twins James Michael and William Patrick (8/6/1866), and George (1874) with his second wife Johanna. The 1870 and 1880 enumerations indicated that Daniel was employed in a Natick shoe factory, and in 1880 further noted that he had some lung trouble, possibly the early stages of tuberculosis, which was unfortunately common at that time. He would die in 1893, leaving Johanna as a widow with two teenagers, George and Thomas.It is unclear where Thomas got his musical training, although some of it was inevitably in the public school system, as indicated in his Boston Globe obituary. He had additional instruction in violin, and likely in harmony, theory, and even possibly orchestration. During his high school years, Allen organized a small orchestra which played at social affairs and entertainments. By the time he was nineteen, Allen was playing publicly in ensembles, and directing from time to time as well. His first publication, Bergen Beach March, was self-issued when he was still nineteen in mid-1896. It was followed a year or so later by You Be My Girl. Moderate sellers during a turbulent time in the music publishing business, he was encouraged to write even more, and his next piece was the ballad In the Heart of Old New England, coming in 1899. As of late 1898, having just recently been married in Natick to Miss Henrietta Jessie W. Johnston, Thomas was also working regularly as a musician, as noted in the Geneva [New York] Daily Times of September 29, 1898. It noted him as leading "a solo orchestra of twelve musical artists" for the Arthur Deming minstrel troupe. But traditional minstrel music was quickly being routed out by the new cakewalks and ragtime, and Allen was ready for the challenge as the new century approached.

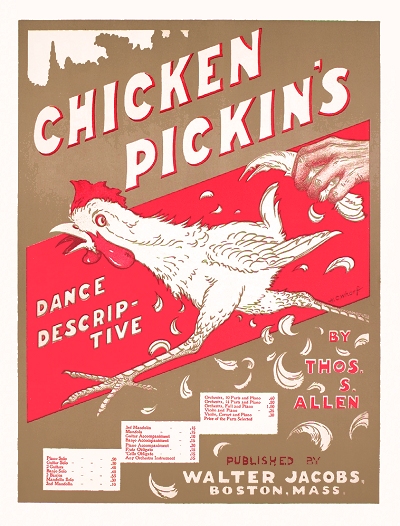

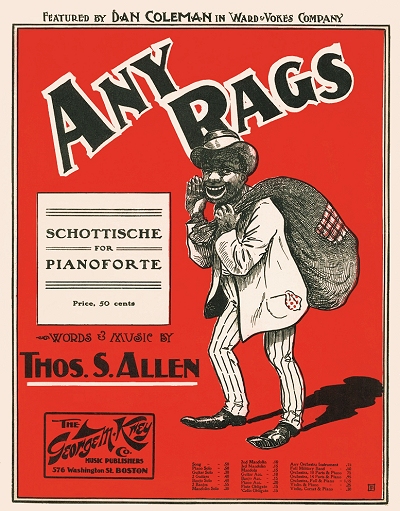

The 1900 census indicated that Thomas and Jessie were now living in Boston proper, and Thomas claimed the occupation of musician. He started composing more regularly, eventually turning out a fine stream of marches and characteristic tunes, largely geared toward dance orchestras, but also published for piano. But he also issued some works through publisher Walter Jacobs arranged for piano as well, among the earliest of them being Chicken Pickin's. While not quite ragtime, it was a neat little dotted-rhythm schottische that was a nod in that direction. In 1901 Allen approached several different styles including waltzes, marches, Latin dances, and even some classical, such as a miniature suite including an overture, entr'acte and descriptive scenes. There were reports in Boston and regional newspapers about his playing these and other pieces while fronting various musical groups with his violin. Then, 1902, George M. Krey issued Allen's Any Rags which quickly became popular. It was another schottische in 4/4 time with a few cakewalk rhythms, and no real ragtime syncopation, but the piece was relatively easy to pick up and quite listenable. Originally published with a chorus over the second strain, Allen penned words for the entire work, sans the trio, for a 1903 song release, a common practice during the ragtime era. Popular baritone Arthur Collins, known as the "King of the Ragtime Singers," popularized the piece on both Edison cylinders and Victor records, helping to cement Allen's reputation as a composer. Another Allen issuance of 1902 was Thomas and Jessie's son Arthur Johnston Allen, born on March 23.

But he also issued some works through publisher Walter Jacobs arranged for piano as well, among the earliest of them being Chicken Pickin's. While not quite ragtime, it was a neat little dotted-rhythm schottische that was a nod in that direction. In 1901 Allen approached several different styles including waltzes, marches, Latin dances, and even some classical, such as a miniature suite including an overture, entr'acte and descriptive scenes. There were reports in Boston and regional newspapers about his playing these and other pieces while fronting various musical groups with his violin. Then, 1902, George M. Krey issued Allen's Any Rags which quickly became popular. It was another schottische in 4/4 time with a few cakewalk rhythms, and no real ragtime syncopation, but the piece was relatively easy to pick up and quite listenable. Originally published with a chorus over the second strain, Allen penned words for the entire work, sans the trio, for a 1903 song release, a common practice during the ragtime era. Popular baritone Arthur Collins, known as the "King of the Ragtime Singers," popularized the piece on both Edison cylinders and Victor records, helping to cement Allen's reputation as a composer. Another Allen issuance of 1902 was Thomas and Jessie's son Arthur Johnston Allen, born on March 23.

But he also issued some works through publisher Walter Jacobs arranged for piano as well, among the earliest of them being Chicken Pickin's. While not quite ragtime, it was a neat little dotted-rhythm schottische that was a nod in that direction. In 1901 Allen approached several different styles including waltzes, marches, Latin dances, and even some classical, such as a miniature suite including an overture, entr'acte and descriptive scenes. There were reports in Boston and regional newspapers about his playing these and other pieces while fronting various musical groups with his violin. Then, 1902, George M. Krey issued Allen's Any Rags which quickly became popular. It was another schottische in 4/4 time with a few cakewalk rhythms, and no real ragtime syncopation, but the piece was relatively easy to pick up and quite listenable. Originally published with a chorus over the second strain, Allen penned words for the entire work, sans the trio, for a 1903 song release, a common practice during the ragtime era. Popular baritone Arthur Collins, known as the "King of the Ragtime Singers," popularized the piece on both Edison cylinders and Victor records, helping to cement Allen's reputation as a composer. Another Allen issuance of 1902 was Thomas and Jessie's son Arthur Johnston Allen, born on March 23.

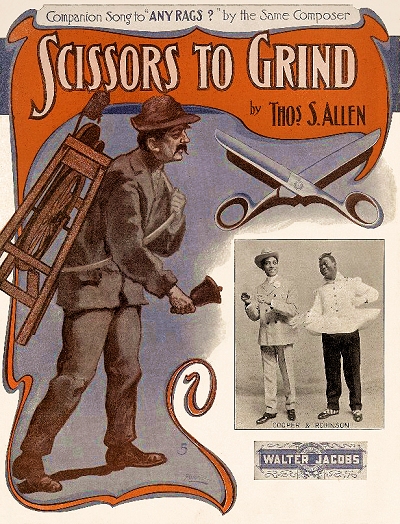

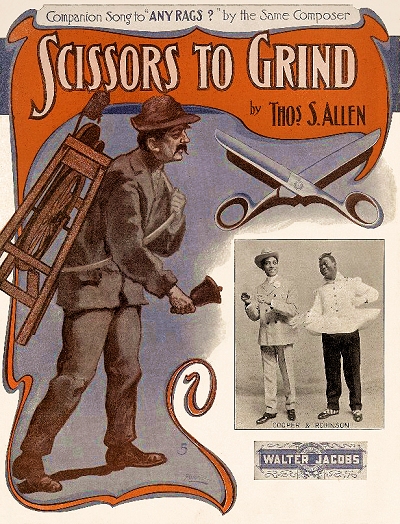

But he also issued some works through publisher Walter Jacobs arranged for piano as well, among the earliest of them being Chicken Pickin's. While not quite ragtime, it was a neat little dotted-rhythm schottische that was a nod in that direction. In 1901 Allen approached several different styles including waltzes, marches, Latin dances, and even some classical, such as a miniature suite including an overture, entr'acte and descriptive scenes. There were reports in Boston and regional newspapers about his playing these and other pieces while fronting various musical groups with his violin. Then, 1902, George M. Krey issued Allen's Any Rags which quickly became popular. It was another schottische in 4/4 time with a few cakewalk rhythms, and no real ragtime syncopation, but the piece was relatively easy to pick up and quite listenable. Originally published with a chorus over the second strain, Allen penned words for the entire work, sans the trio, for a 1903 song release, a common practice during the ragtime era. Popular baritone Arthur Collins, known as the "King of the Ragtime Singers," popularized the piece on both Edison cylinders and Victor records, helping to cement Allen's reputation as a composer. Another Allen issuance of 1902 was Thomas and Jessie's son Arthur Johnston Allen, born on March 23.In 1903 Thomas became the director of the Howard Theater in Boston, conducting for stage shows and programming special concerts. While the steady work kept him from composing as much, he caught up in 1904, with both Jacobs and Krey releasing several of his works. The most popular of them was another schottische also turned into a song, By the Watermelon Vine, Lindy Lou. Taking a close second was the mixed-ethnicity Scissors to Grind. While the Starmer Brothers cover clearly shows an Italian street vendor with his portable grinding wheel equipment, somewhat in the guise of the rag merchant on Any Rags, Allen's lyrics, which also allude to rags, have a tone that is clearly leaning more toward the stereotypical black dialect of the era as portrayed in "coon" songs. Whether or not Thomas was deliberately trying to infuse more of a New York City vibe into his piece than of Boston is unclear, but the song did get some play and subsequent recordings. Allen spent the next couple of summer and fall seasons as the leader of a nine-piece orchestra at Freebody Park in Newport, Rhode Island, a popular resort location. In 1905 he worked the orchestra at Boston's Paragon Park, even penning a nice waltz tune in honor of the venue.

The most popular of them was another schottische also turned into a song, By the Watermelon Vine, Lindy Lou. Taking a close second was the mixed-ethnicity Scissors to Grind. While the Starmer Brothers cover clearly shows an Italian street vendor with his portable grinding wheel equipment, somewhat in the guise of the rag merchant on Any Rags, Allen's lyrics, which also allude to rags, have a tone that is clearly leaning more toward the stereotypical black dialect of the era as portrayed in "coon" songs. Whether or not Thomas was deliberately trying to infuse more of a New York City vibe into his piece than of Boston is unclear, but the song did get some play and subsequent recordings. Allen spent the next couple of summer and fall seasons as the leader of a nine-piece orchestra at Freebody Park in Newport, Rhode Island, a popular resort location. In 1905 he worked the orchestra at Boston's Paragon Park, even penning a nice waltz tune in honor of the venue.

The most popular of them was another schottische also turned into a song, By the Watermelon Vine, Lindy Lou. Taking a close second was the mixed-ethnicity Scissors to Grind. While the Starmer Brothers cover clearly shows an Italian street vendor with his portable grinding wheel equipment, somewhat in the guise of the rag merchant on Any Rags, Allen's lyrics, which also allude to rags, have a tone that is clearly leaning more toward the stereotypical black dialect of the era as portrayed in "coon" songs. Whether or not Thomas was deliberately trying to infuse more of a New York City vibe into his piece than of Boston is unclear, but the song did get some play and subsequent recordings. Allen spent the next couple of summer and fall seasons as the leader of a nine-piece orchestra at Freebody Park in Newport, Rhode Island, a popular resort location. In 1905 he worked the orchestra at Boston's Paragon Park, even penning a nice waltz tune in honor of the venue.

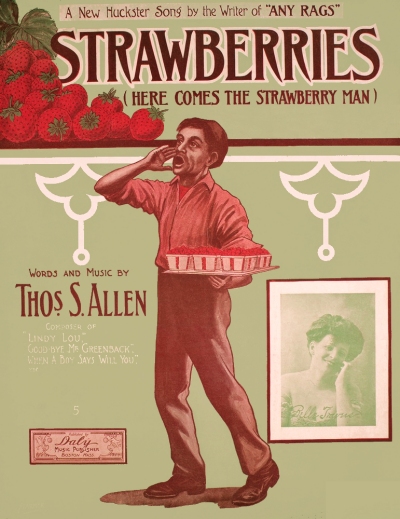

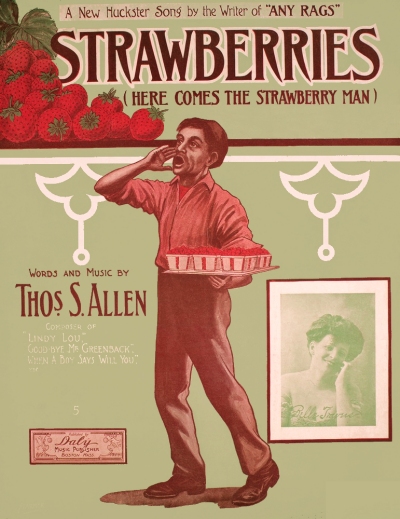

The most popular of them was another schottische also turned into a song, By the Watermelon Vine, Lindy Lou. Taking a close second was the mixed-ethnicity Scissors to Grind. While the Starmer Brothers cover clearly shows an Italian street vendor with his portable grinding wheel equipment, somewhat in the guise of the rag merchant on Any Rags, Allen's lyrics, which also allude to rags, have a tone that is clearly leaning more toward the stereotypical black dialect of the era as portrayed in "coon" songs. Whether or not Thomas was deliberately trying to infuse more of a New York City vibe into his piece than of Boston is unclear, but the song did get some play and subsequent recordings. Allen spent the next couple of summer and fall seasons as the leader of a nine-piece orchestra at Freebody Park in Newport, Rhode Island, a popular resort location. In 1905 he worked the orchestra at Boston's Paragon Park, even penning a nice waltz tune in honor of the venue.Rising up in the ranks, Allen became the musical director of the prestigious 2,000 seat Tremont Theatre managed by producers Klaw and Erlanger. (It was replaced in the 1980s by a Loew's multiplex movie theater in the same location.) He was responsible for vaudeville and stage entertainments as well as concerts of popular and classical music. In the interim he found time to turn out a handful of pieces over each of the next few years, most following popular trends such as ethnically-themed works, marches, waltzes, and even a coon song. In 1907 his Hoop-E-Kack got some traction as a novelty dance number, likely played when he did summer dance hall venues. Then in 1909, he came up with the instrumental Strawberries, later appended with lyrics to become Here Comes the Strawberry Man. It recounts the tale of the strawberry vendor who endeavors to become an opera singer, only to find out after a few years that he is better suited as a strawberry vendor. It is notable for mentioning Italian operatic composer Pietro Mascagni, whose Cavalleria Rusticacana had found its way through various themes into other popular works, including Strawberries. Mascagni had actually been to Boston a few years prior on a financially disastrous tour which involved his unpaid musicians walking out on him, and serving some jail time for unpaid debts. He was eventually able to return home after working menial gigs around town. It is unclear if Allen was involved with any of the debacle which took place in early 1903, but being musically connected as he was in the city, he was certainly aware of it, as were most Bostonians. Allen's latest work found its way onto disc once again, thanks to Arthur Collins among others, who turned in hearty imitations of the strawberry vendor in an Italian-ish dialect.

Mascagni had actually been to Boston a few years prior on a financially disastrous tour which involved his unpaid musicians walking out on him, and serving some jail time for unpaid debts. He was eventually able to return home after working menial gigs around town. It is unclear if Allen was involved with any of the debacle which took place in early 1903, but being musically connected as he was in the city, he was certainly aware of it, as were most Bostonians. Allen's latest work found its way onto disc once again, thanks to Arthur Collins among others, who turned in hearty imitations of the strawberry vendor in an Italian-ish dialect.

Mascagni had actually been to Boston a few years prior on a financially disastrous tour which involved his unpaid musicians walking out on him, and serving some jail time for unpaid debts. He was eventually able to return home after working menial gigs around town. It is unclear if Allen was involved with any of the debacle which took place in early 1903, but being musically connected as he was in the city, he was certainly aware of it, as were most Bostonians. Allen's latest work found its way onto disc once again, thanks to Arthur Collins among others, who turned in hearty imitations of the strawberry vendor in an Italian-ish dialect.

Mascagni had actually been to Boston a few years prior on a financially disastrous tour which involved his unpaid musicians walking out on him, and serving some jail time for unpaid debts. He was eventually able to return home after working menial gigs around town. It is unclear if Allen was involved with any of the debacle which took place in early 1903, but being musically connected as he was in the city, he was certainly aware of it, as were most Bostonians. Allen's latest work found its way onto disc once again, thanks to Arthur Collins among others, who turned in hearty imitations of the strawberry vendor in an Italian-ish dialect.From 1908 to 1910, Thomas had his own music company at 218 Tremont Street. With many of the pieces he published, especially the orchestra versions, he also had illustrated slides to accompany them produced by the North American Slide Company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In some of his advertisements in The Billboard and other trade papers, he listed himself as a "music carver," which could translate to engraver, although he likely either contracted that duty out or had an employee in-house who took on such duties. As early as 1906 he scored another fine position, leading Allen's Singing Orchestra at Norumbega Park in Boston for the summer and fall, and had continued there with notices in the trades through at least 1909. In spite of these continuing successes for Allen, his home life was not so successful. Around the time their second child, Gladys, was born in late 1909, Jessie had abandoned the nest leaving Thomas alone. The April, 1910, census showed him as divorced and lodging in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston. It is unclear what happened to Jessie that year, but the children appeared to be in a temporary foster care situation in a boarding house, perhaps with a relative, Eva M. Fairbanks. Jessie was not readily found in that enumeration, possibly having even changed her name during her disappearance.

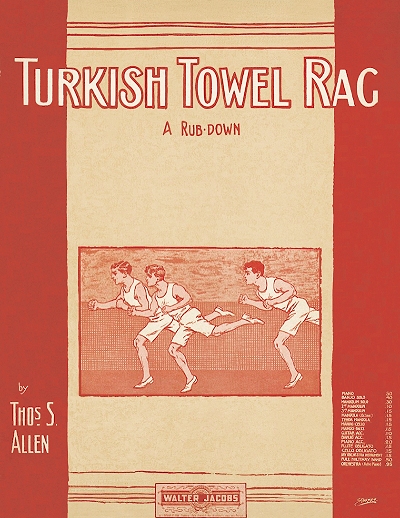

Thomas soldiered on, keeping busy with engagements and increasing his compositional output. Most of his work at this time, following the collapse of his own company, was issued by Walter Jacobs. They again covered the spectrum from genteel waltzes and light ballads to the occasional pseudo-syncopated instrumental, most of the latter pieces with a detectable violin-centric melodic line. However, in 1912 Jacobs issued Allen's fine authentic piano rag, Turkish Towel, which became a good seller for the company. Full of real ragtime syncopation, this may have been his best contribution to that genre. A couple more similar works would appear in 1913, but not to the same acclaim. One other work that appeared has since been learned by folk singers and school children alike. It is uncertain if Allen completely wrote the piece, or if he solidified it from a collection of folk melodies and lyrics. However, he has been largely credited with the 1912 piece Low Bridge, more commonly known as Fifteen Years on the Erie Canal, and in later renditions, Fifteen Miles on the Erie Canal. Essentially a story of canal life from the point of view of the owner of a mule named Sal at a time when horses and mules provided the motive power on this important waterway, it has retained its importance in American culture almost since it was first published. This indelible work, which was issued soon after an announcement was made that an unused portion of the canal would be closed for good, was performed by singer Billy Murray as well as the Peerless Quartet in 1912 closely following its debut in print.

They again covered the spectrum from genteel waltzes and light ballads to the occasional pseudo-syncopated instrumental, most of the latter pieces with a detectable violin-centric melodic line. However, in 1912 Jacobs issued Allen's fine authentic piano rag, Turkish Towel, which became a good seller for the company. Full of real ragtime syncopation, this may have been his best contribution to that genre. A couple more similar works would appear in 1913, but not to the same acclaim. One other work that appeared has since been learned by folk singers and school children alike. It is uncertain if Allen completely wrote the piece, or if he solidified it from a collection of folk melodies and lyrics. However, he has been largely credited with the 1912 piece Low Bridge, more commonly known as Fifteen Years on the Erie Canal, and in later renditions, Fifteen Miles on the Erie Canal. Essentially a story of canal life from the point of view of the owner of a mule named Sal at a time when horses and mules provided the motive power on this important waterway, it has retained its importance in American culture almost since it was first published. This indelible work, which was issued soon after an announcement was made that an unused portion of the canal would be closed for good, was performed by singer Billy Murray as well as the Peerless Quartet in 1912 closely following its debut in print.

They again covered the spectrum from genteel waltzes and light ballads to the occasional pseudo-syncopated instrumental, most of the latter pieces with a detectable violin-centric melodic line. However, in 1912 Jacobs issued Allen's fine authentic piano rag, Turkish Towel, which became a good seller for the company. Full of real ragtime syncopation, this may have been his best contribution to that genre. A couple more similar works would appear in 1913, but not to the same acclaim. One other work that appeared has since been learned by folk singers and school children alike. It is uncertain if Allen completely wrote the piece, or if he solidified it from a collection of folk melodies and lyrics. However, he has been largely credited with the 1912 piece Low Bridge, more commonly known as Fifteen Years on the Erie Canal, and in later renditions, Fifteen Miles on the Erie Canal. Essentially a story of canal life from the point of view of the owner of a mule named Sal at a time when horses and mules provided the motive power on this important waterway, it has retained its importance in American culture almost since it was first published. This indelible work, which was issued soon after an announcement was made that an unused portion of the canal would be closed for good, was performed by singer Billy Murray as well as the Peerless Quartet in 1912 closely following its debut in print.

They again covered the spectrum from genteel waltzes and light ballads to the occasional pseudo-syncopated instrumental, most of the latter pieces with a detectable violin-centric melodic line. However, in 1912 Jacobs issued Allen's fine authentic piano rag, Turkish Towel, which became a good seller for the company. Full of real ragtime syncopation, this may have been his best contribution to that genre. A couple more similar works would appear in 1913, but not to the same acclaim. One other work that appeared has since been learned by folk singers and school children alike. It is uncertain if Allen completely wrote the piece, or if he solidified it from a collection of folk melodies and lyrics. However, he has been largely credited with the 1912 piece Low Bridge, more commonly known as Fifteen Years on the Erie Canal, and in later renditions, Fifteen Miles on the Erie Canal. Essentially a story of canal life from the point of view of the owner of a mule named Sal at a time when horses and mules provided the motive power on this important waterway, it has retained its importance in American culture almost since it was first published. This indelible work, which was issued soon after an announcement was made that an unused portion of the canal would be closed for good, was performed by singer Billy Murray as well as the Peerless Quartet in 1912 closely following its debut in print.In 1913, however, Thomas started writing songs more frequently with composer and sometimes-publisher Joseph M. Daly. The pair had issued a song in 1910, Just for a Dear Little Girl, and Daly had published some of Allen's works, having possibly got a better deal with him than he had with Jacobs. Joseph called on Thomas to supply or at least rewrite lyrics for several of his works. At least as indicated on the copyrights and the music covers, their entire output was with Thomas as lyricist and Daly as composer, although some crossover was likely. Among their hits of 1913 were The Pussy Cat Rag (Kitty, Kitty, Kitty) and the still frequently seen (in antique malls and on eBay) but not heard What D'ye Mean You Lost Yer Dog?. One of their songs that saw some recordings and many stage performances was the poignant but otherwise ordinary ballad In the Heart of the City That Has No Heart.

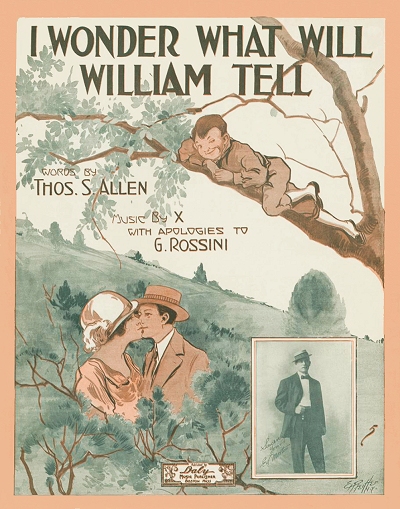

Both 1913 and 1914 were particularly productive for Allen as a composer. In addition to the usual fare, he made another contribution to the classics-turned-popular category, albeit in disguise. For I Wonder What Will William Tell, which was more about an annoying spying little brother than it was about apples and archery, he admitted to the lyrics, but for his adaptation (which could also possibly have been rendered by the unmentioned Daly) of the famous Gioachino Rossini overture in both the verse and chorus, he attributed it to "X with apologies to G. Rossini." It was a cute novelty number that got its fair share of recordings and performances. In 1915, on the road a bit more with traveling shows, Allen's output slowed, but included the interesting works Sandy River Rag, The Battleship Rag, and Stop! Look! and Listen!, billed as a railroad fox trot. With Daly he penned The Birth of a Nation, which despite sharing the name of the controversial Civil War film released that year by director David W. Griffith, was actually about the birth of the United States back in 1776. Allen's subsequent works from 1916 forward were mostly published by Jacobs in numerous band folios, and in his Jacobs' Band Monthly magazine. One of them from 1916 was a march titled Conscription, possibly alluding to the veiled inevitability of a draft to bring the United States into the ongoing conflict in Europe, although before President Woodrow Wilson had been reelected, so ultimately unclear as to the direct reference.

For I Wonder What Will William Tell, which was more about an annoying spying little brother than it was about apples and archery, he admitted to the lyrics, but for his adaptation (which could also possibly have been rendered by the unmentioned Daly) of the famous Gioachino Rossini overture in both the verse and chorus, he attributed it to "X with apologies to G. Rossini." It was a cute novelty number that got its fair share of recordings and performances. In 1915, on the road a bit more with traveling shows, Allen's output slowed, but included the interesting works Sandy River Rag, The Battleship Rag, and Stop! Look! and Listen!, billed as a railroad fox trot. With Daly he penned The Birth of a Nation, which despite sharing the name of the controversial Civil War film released that year by director David W. Griffith, was actually about the birth of the United States back in 1776. Allen's subsequent works from 1916 forward were mostly published by Jacobs in numerous band folios, and in his Jacobs' Band Monthly magazine. One of them from 1916 was a march titled Conscription, possibly alluding to the veiled inevitability of a draft to bring the United States into the ongoing conflict in Europe, although before President Woodrow Wilson had been reelected, so ultimately unclear as to the direct reference.

For I Wonder What Will William Tell, which was more about an annoying spying little brother than it was about apples and archery, he admitted to the lyrics, but for his adaptation (which could also possibly have been rendered by the unmentioned Daly) of the famous Gioachino Rossini overture in both the verse and chorus, he attributed it to "X with apologies to G. Rossini." It was a cute novelty number that got its fair share of recordings and performances. In 1915, on the road a bit more with traveling shows, Allen's output slowed, but included the interesting works Sandy River Rag, The Battleship Rag, and Stop! Look! and Listen!, billed as a railroad fox trot. With Daly he penned The Birth of a Nation, which despite sharing the name of the controversial Civil War film released that year by director David W. Griffith, was actually about the birth of the United States back in 1776. Allen's subsequent works from 1916 forward were mostly published by Jacobs in numerous band folios, and in his Jacobs' Band Monthly magazine. One of them from 1916 was a march titled Conscription, possibly alluding to the veiled inevitability of a draft to bring the United States into the ongoing conflict in Europe, although before President Woodrow Wilson had been reelected, so ultimately unclear as to the direct reference.

For I Wonder What Will William Tell, which was more about an annoying spying little brother than it was about apples and archery, he admitted to the lyrics, but for his adaptation (which could also possibly have been rendered by the unmentioned Daly) of the famous Gioachino Rossini overture in both the verse and chorus, he attributed it to "X with apologies to G. Rossini." It was a cute novelty number that got its fair share of recordings and performances. In 1915, on the road a bit more with traveling shows, Allen's output slowed, but included the interesting works Sandy River Rag, The Battleship Rag, and Stop! Look! and Listen!, billed as a railroad fox trot. With Daly he penned The Birth of a Nation, which despite sharing the name of the controversial Civil War film released that year by director David W. Griffith, was actually about the birth of the United States back in 1776. Allen's subsequent works from 1916 forward were mostly published by Jacobs in numerous band folios, and in his Jacobs' Band Monthly magazine. One of them from 1916 was a march titled Conscription, possibly alluding to the veiled inevitability of a draft to bring the United States into the ongoing conflict in Europe, although before President Woodrow Wilson had been reelected, so ultimately unclear as to the direct reference.Being on the road in 1916 and 1917, Allen, now in his forties, was more focused on his directing duties than writing, so his output slowed greatly. Some of the Jacobs issues may have been backlogged, so composed some years before their appearance in folios and orchestra arrangements. In 1917 Thomas was engaged by performer and producer Harry Hastings for his burlesque entertainment, Harry Hastings' Big Show. It was largely ethnic Irish humor with a variety of vaudeville-like acts and a dancing chorus. Allen is mentioned in some newspaper notices of the time as having provided music for the affair, which had been going since at least 1914. As musical director, he was part of the troupe from late 1917 through early 1919, traveling around the East, Northeast and Midwest of the United States, and the fringes of southern Canada. Most of the reviews, while not quite ebullient, did mention the show to be competent and relatively clean, and some singled out Allen's contributions. Copyright records show that he cowrote one of the shows for Hastings with lyricist and show director Dan Coleman, of which only the title tune, After the First of July, an anti-prohibition song, was published. Allen's September 12, 1918, final call draft record taken in Boston showed him as working for Hastings who was based in the Columbia Theatre Building, and listed his older brother James as his point of contact.

Thomas had grown ill by mid-to-late-1918, but did not know yet what the ailment was. Growing increasingly weak through the end of the year and into 1919, he finally collapsed after a matinee in Syracuse, New York, at the Bastable Theater, on April 10, 1919. According to multiple news reports, doctors found that an operation was necessary, and was undertaken in Rochester the following day. What they found was initially reported as stomach cancer, but the malady was actually much worse. Thomas spent the next six months in care and hospice, finally succumbing to colorectal cancer on October 23. He was buried in Natick in a family plot near his parents. Thomas was survived by his wife and son, the latter who was serving in the United States Navy. His music, both serious and whimsical, is still with us a century later.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions