There are times when the search for information on a composer, whose small but significant set of works are fairly well-known, seems fruitless and frustrating. The case of Thomas E. Broady has been one of those for years. While a bit of newer data was discovered for this essay, it is still sadly lacking in detail, perhaps due to the under-reporting of the lives of people of color by traditional sources in the early 20th century. However, what has been collected will tell at least some semblance of a story about a musician who had potential, but also had many barriers to break through to realize that potential, only to end up unjustly as a footnote of early ragtime piano history.

Thomas was the youngest of six siblings born in or near Carni in southeast Illinois in 1877. His parents, Henry A. Broady and his wife Martha A. were both freeborn blacks. Actually, Henry's mother was fully black as were his three older siblings, but he was born an illegitimate mulatto child under unknown circumstances to a white father, which was a potential issue for him growing up, both with his siblings and others in the community. This may have given him reason to make sure his children excelled in their own lives. They included Eliza (1860), James Franklin "Frank" (1862), William (1864), Henry (1869) and Alexander V. (1875). The 1870 enumeration showed the family living in Carni, the White County seat, but by 1880 they were living in nearby Hawthorn. In both records, Henry was shown working as a plasterer. Also in 1880, both Frank and William were working as farm laborers. The entire family was listed as mulatto for the enumeration that year.

Actually, Henry's mother was fully black as were his three older siblings, but he was born an illegitimate mulatto child under unknown circumstances to a white father, which was a potential issue for him growing up, both with his siblings and others in the community. This may have given him reason to make sure his children excelled in their own lives. They included Eliza (1860), James Franklin "Frank" (1862), William (1864), Henry (1869) and Alexander V. (1875). The 1870 enumeration showed the family living in Carni, the White County seat, but by 1880 they were living in nearby Hawthorn. In both records, Henry was shown working as a plasterer. Also in 1880, both Frank and William were working as farm laborers. The entire family was listed as mulatto for the enumeration that year.

Actually, Henry's mother was fully black as were his three older siblings, but he was born an illegitimate mulatto child under unknown circumstances to a white father, which was a potential issue for him growing up, both with his siblings and others in the community. This may have given him reason to make sure his children excelled in their own lives. They included Eliza (1860), James Franklin "Frank" (1862), William (1864), Henry (1869) and Alexander V. (1875). The 1870 enumeration showed the family living in Carni, the White County seat, but by 1880 they were living in nearby Hawthorn. In both records, Henry was shown working as a plasterer. Also in 1880, both Frank and William were working as farm laborers. The entire family was listed as mulatto for the enumeration that year.

Actually, Henry's mother was fully black as were his three older siblings, but he was born an illegitimate mulatto child under unknown circumstances to a white father, which was a potential issue for him growing up, both with his siblings and others in the community. This may have given him reason to make sure his children excelled in their own lives. They included Eliza (1860), James Franklin "Frank" (1862), William (1864), Henry (1869) and Alexander V. (1875). The 1870 enumeration showed the family living in Carni, the White County seat, but by 1880 they were living in nearby Hawthorn. In both records, Henry was shown working as a plasterer. Also in 1880, both Frank and William were working as farm laborers. The entire family was listed as mulatto for the enumeration that year.By 1887 the Broadys were relocated to the state capitol of Springfield, Illinois, where Henry continued his career as a plasterer in the growing community. Alexander and Thomas, both still in school, no doubt benefitted from the better education available to them in this city. Evidence suggests by inference that Thomas pursued music in some manner, either through the schools or perhaps private lessons. He graduated from Springfield High School in 1896. A class picture from his the yearbook indicates that he may have been the only African-American in that class. The family was shown living at 403 N. 14th Street at that time, with William also working as a plasterer, and Alex as a stenographer. That same year, Thomas had a march song published in Springfield titled Constancy according to copyright records, but little else is known of it.

An article in the Daily Illinois State Journal of March 15, 1896, showed that Thomas was the assistant manager and instrumental director of the recently-chartered Colored Musical Union of Springfield. His brother Henry helped with the by-laws for the new group. Another article from June 11 indicated that he was also versed in strings, performing for a high school function on the mandolin as part of a trio. While the rest of 1896 into 1897 is unaccounted for overall, it appears that Thomas secured a position with the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in Nashville. The Illinois State Register of April 24, 1897, noted that he was headed to Nashville to work at the fairgrounds.

Soon after he was in Tennessee, Thomas arranged the Tennessee Centennial March, composed by Nashville resident William E. Braswell, for the piano, and it was published in mid-1897. This work was clearly intended to honor the celebration and coincide with the Exposition. Braswell was otherwise not found to be a musician by trade, likely one of the laborers helping to complete the fairgrounds for the event. Given that all of the remaining known compositions of Broady were published in Nashville from 1897 to 1900, it appeared to be possible that he attended Fisk University in that town. A black school founded less than two years after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, and named for General Clinton B. Fisk, a freedman fighter for the Union Army, one of Fisk's strengths was as a music school. In fact, the initial building that classes were held in, Jubilee Hall, was built largely from proceeds generated by their singing touring group, the now world-renowned Jubilee Singers. They started touring in 1871 singing spirituals and other music in a serious and studied manner. They also had programs that were quite flexible in terms of allowing people of color of even meager financial status to attend, as long as they excelled in their studies. However, although his name showed up in one of their records, this was not the case. The timeline is unclear, but from at least 1899 into 1901 Thomas was shown to be a student at Meharry Medical College in Nashville. Meharry had been founded in 1876 by the Methodist Church as part of Central Tennessee College to ensure not only that black students could enter the medical profession, but so they could attend to an underserved African-American community in the United States.

Given that all of the remaining known compositions of Broady were published in Nashville from 1897 to 1900, it appeared to be possible that he attended Fisk University in that town. A black school founded less than two years after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, and named for General Clinton B. Fisk, a freedman fighter for the Union Army, one of Fisk's strengths was as a music school. In fact, the initial building that classes were held in, Jubilee Hall, was built largely from proceeds generated by their singing touring group, the now world-renowned Jubilee Singers. They started touring in 1871 singing spirituals and other music in a serious and studied manner. They also had programs that were quite flexible in terms of allowing people of color of even meager financial status to attend, as long as they excelled in their studies. However, although his name showed up in one of their records, this was not the case. The timeline is unclear, but from at least 1899 into 1901 Thomas was shown to be a student at Meharry Medical College in Nashville. Meharry had been founded in 1876 by the Methodist Church as part of Central Tennessee College to ensure not only that black students could enter the medical profession, but so they could attend to an underserved African-American community in the United States.

Given that all of the remaining known compositions of Broady were published in Nashville from 1897 to 1900, it appeared to be possible that he attended Fisk University in that town. A black school founded less than two years after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, and named for General Clinton B. Fisk, a freedman fighter for the Union Army, one of Fisk's strengths was as a music school. In fact, the initial building that classes were held in, Jubilee Hall, was built largely from proceeds generated by their singing touring group, the now world-renowned Jubilee Singers. They started touring in 1871 singing spirituals and other music in a serious and studied manner. They also had programs that were quite flexible in terms of allowing people of color of even meager financial status to attend, as long as they excelled in their studies. However, although his name showed up in one of their records, this was not the case. The timeline is unclear, but from at least 1899 into 1901 Thomas was shown to be a student at Meharry Medical College in Nashville. Meharry had been founded in 1876 by the Methodist Church as part of Central Tennessee College to ensure not only that black students could enter the medical profession, but so they could attend to an underserved African-American community in the United States.

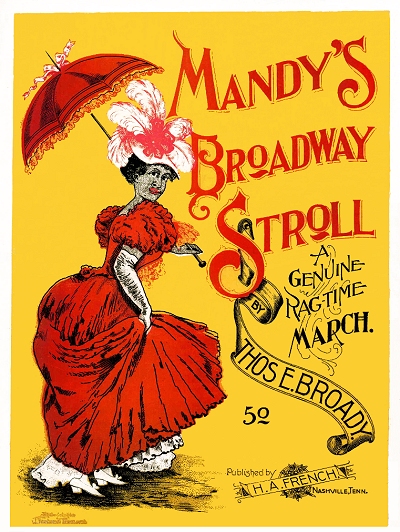

Given that all of the remaining known compositions of Broady were published in Nashville from 1897 to 1900, it appeared to be possible that he attended Fisk University in that town. A black school founded less than two years after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, and named for General Clinton B. Fisk, a freedman fighter for the Union Army, one of Fisk's strengths was as a music school. In fact, the initial building that classes were held in, Jubilee Hall, was built largely from proceeds generated by their singing touring group, the now world-renowned Jubilee Singers. They started touring in 1871 singing spirituals and other music in a serious and studied manner. They also had programs that were quite flexible in terms of allowing people of color of even meager financial status to attend, as long as they excelled in their studies. However, although his name showed up in one of their records, this was not the case. The timeline is unclear, but from at least 1899 into 1901 Thomas was shown to be a student at Meharry Medical College in Nashville. Meharry had been founded in 1876 by the Methodist Church as part of Central Tennessee College to ensure not only that black students could enter the medical profession, but so they could attend to an underserved African-American community in the United States.Thomas's mother Martha died in 1897, leaving his dad as a widower. After the Exposition Tom clearly stayed in the host city. He composed Mandy's Broadway Stroll in 1898. It was more rag than cakewalk in nature and fairly well-developed overall, including a trio interlude, but with only a moderately competent arrangement. The publisher was Henry A. French who would soon also take on the rags of blind Tennessee native Charles Hunter. There is no indication that the two composers knew each other, but as Hunter was working in Nashville as a piano tuner for Henry's brother, Jesse French, they may have met in passing. The cover of Mandy's Broadway Stroll alarmingly showed what appeared to be a black prostitute, given that she was wearing bright lipstick and a red dress. While this may not have been the intent, there are mentions in historical texts that red light district of Nashville was along Broadway and it was referred to as "the stroll."

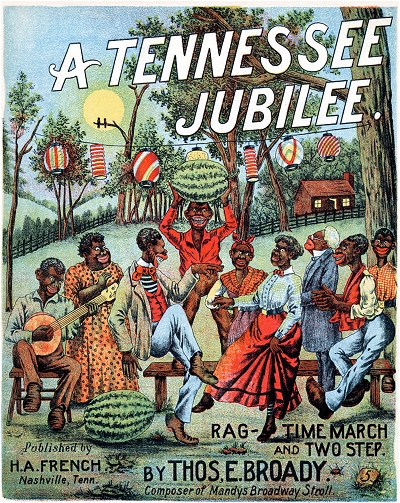

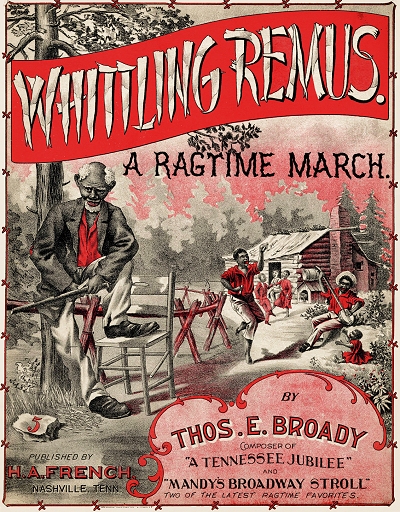

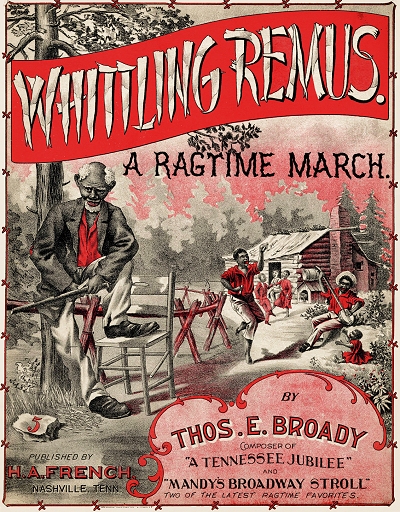

In 1899 French published Tom's next known work, A Tennessee Jubilee. The four-color and black cover was very similar to those currently being turned out on pieces published by E.T. Paull in New York City, and was an excellent exception for French's firm, despite the clear stereotypes portrayed in the artwork. While it is unclear if Broady attended Fisk at any juncture, given the Jubilee reference, and that it was the name of an earlier Tennessee performing troupe, he may have at least known other students there. This was again very much like a cakewalk, but with rag conventions factored in, including some over-the-barline syncopations. Tom followed this piece up in 1900 with Whittling Remus, which many performers and historians consider as his finest work. As it turns out it was also his last-known published tune. The trio is interestingly developed with an interlude that serves as a fine transition back into that trio, suggesting a slower tempo on the reprise. All three of Broady's ragtime works are still performed and recorded more than a century later.

As it turns out it was also his last-known published tune. The trio is interestingly developed with an interlude that serves as a fine transition back into that trio, suggesting a slower tempo on the reprise. All three of Broady's ragtime works are still performed and recorded more than a century later.

As it turns out it was also his last-known published tune. The trio is interestingly developed with an interlude that serves as a fine transition back into that trio, suggesting a slower tempo on the reprise. All three of Broady's ragtime works are still performed and recorded more than a century later.

As it turns out it was also his last-known published tune. The trio is interestingly developed with an interlude that serves as a fine transition back into that trio, suggesting a slower tempo on the reprise. All three of Broady's ragtime works are still performed and recorded more than a century later.Then the music ceased, at least the published works. The 1900 enumeration showed that Thomas was back in Springfield living with his father and some of his siblings, listed still as a college student, and other evidence suggests he went back to Meharry Medical College for at least one more semester or year. It is unclear if he obtained a degree from the school. From there the trail is difficult to follow. A 1902 alumnus report from Springfield High School indicated that he was working now as a Pullman train car porter in Saint Louis, Missouri, where much of the ragtime action was at that time, and living at 2834 LaClede Avenue. A 1903 Saint Louis directory helps to reinforce this, showing Broady as a porter, but now at 2222 Walnut. He was evidently still involved in music in the ragtime community, but not making much, if any, of a living from it. Thomas is mentioned in a Saint Louis Palladium item on the "Rose Bud [sic] Ball" in their February 27th, 1904, edition, a couple of months ahead of the opening of the Saint Louis World's Fair. This event was presided over by the Rosebud Saloon's proprietor Thomas Million "Tom" Turpin, a fine player himself, and indicates that Louis Chauvin had won the prize for a piano competition that evening, which also included Joe Jordan and Charles Warfield, who tied for second. Tom was listed under "Among those present The Palladium man noticed:" indicating that he was a known quantity in Saint Louis at that time.

The trail again goes cold until 1907. The Illinois State Register noted that Thomas E. Broady had died at the Springfield hospital on May 12 at age 29, and was to be interred at the Oak Ridge Cemetery. No apparent cause of death was found, but it was likely medical in nature as no incidents were found in the research indicating otherwise. While some of the veil of mystery has been lifted, there will always be unanswered questions, such as why Tom ceased composing when he did, or at least stopped having pieces published, and what his role was in Saint Louis ragtime around the time of the Lewis and Clark Exposition of 1904.

Most of the information for this essay was based on scant items found in official government records, copyright records, and a couple of newspaper notices. Very little conjecture needed to be applied as the pieces fit into a logical progression in the puzzle that was left behind by Broady. Thanks to performer and historian Terry Parrish who sent a clue that helped out just a bit, and to the late historian Bryan Cather of the Scott Joplin House who forwarded some articles on Broady's time in Springfield in the late 1890s. If there is any information that anybody has concerning Broady's life and his death at age 29, please send it along and you will credited by me and thanked by the ragtime community at large.

Compositions

Compositions