Egbert Anson Van Alstyne (March 5, 1878 to July 9, 1951) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

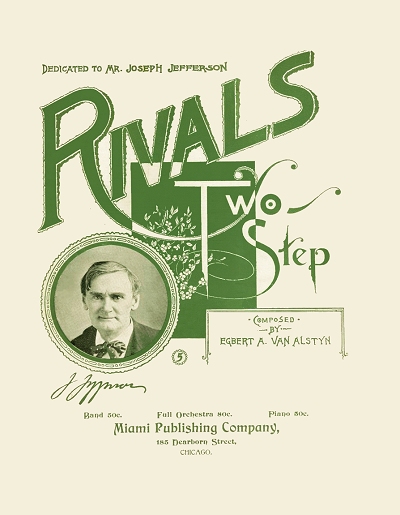

1896

The Rivals Two-Step1897

Mayflower Waltzes1899

Hu-la Hu-la Cakewalk1900

Go To Sleep, Your Mammy's Here BesideYou [1] Bolo Bolo Hearts are Trumps Ragtime Chimes 1901

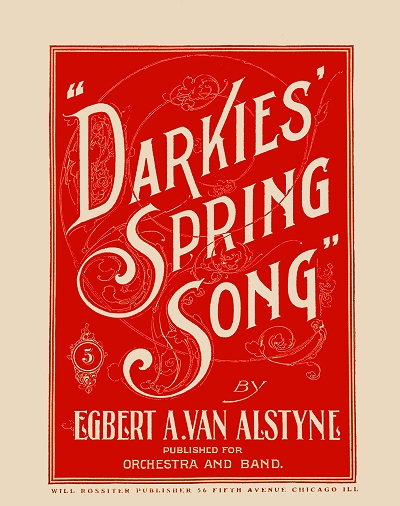

Patocka WaltzesDarkies' Spring Song 1902

Easy Pickin'sPious Peter 1903

Navajo (Navaho) (March)Navajo [2] (Song) My Sweet Magnolia [2] The Storm of Life [2] We've Got to Move Today [2] 1904

Back, Back, Back to Baltimore [2]Farewell, Nellie Mine [2] Ramona (Indian Waltzes) The Tale of the Old Black Crow [2] A-Sa-Ma: Intermezzo [w/Will Hyde] You're All Right Eddie [2] The Temples of Eternity [w/Arthur J. Lamb] Buttercups and Daisies Toreador: Waltzes Ginger Snaps Seminole (March) Seminole (Song) [2] Mr. Wilson (That's All!) [2] If I Were Only You [2] Johnnie Morgan [2] There's a Chicken Dinner Waitin' Home for Me [2] Tippecanoe [2] 1905

Hosanna: Sacred Song [1]Cheyenne (Shy Ann) [2] Sioux Song [2] Good-a-bye John [2] Senorita Papeta [2] Aunt Jane: March (Bolo Bolo) Nicodemus [2] A Man May Go to College and Still Be a Fool [2] The Janitor [2] There's a Little Fighting Blood in Me [2] On a Summer Night [2] In Sunny Little Italy [2] Something Seems to Tell Me I'm in Love With You [2] Get a Ticket [2] Fol-De-Rol-Dol [2] I'm Going Back to California [2] The Cob Web Man [2] Bright Eyes Good-Bye [2] My Hindoo Man [2] In Dear Old Georgia [2] In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree [2] I Wonder What the Wild Waves are Saying [2] Valse Lucile Why Don't You Try (The Rolling Chair Song) [2] Tom Dick and Harry: Musical [2] At West Point Be My Girl My Nightingale Down in Lover's Lane Fight Them Like Your Dear Old Dad Because He Wears That Hat I Forgot the Rhyme Bonita Cachelti Cholly Professor and His Pupil Back to the U.S.A. 1906

Down in the Everglade [2]Not Yet, But Soon [2] Shy Try (Instrumental from Shy Ann and Why Don't You Try) Larry [2] Sally [2] Valse Louise Oh! How I Love My Teacher [2] Shoulder Straps: March I'm Going Right Back to Chicago [2] My Irish Girl [2] I've Got a Vacant Room in My Heart for You [2] When You Kiss the Girl You Love [2] Since Hiram Went to Yale [2] The Little Old Red School House on the Hill [2] I Like You Too [2] What's the Use of Anything [2] Camp Meeting Time (aka Campmeetin' Time) [2] Won't You Come Over To My House [2] Owatonna: Indian Song [2] 1907

In the Land of the Buffalo [2]On An Old Fashioned Buggy Ride [2] A Solitary Finish [2] Your Father Was a Soldier [2] When You See Me With Another Beau [2] Zoo-Lou [2] The Tale the Church Bells Tolled [2] There Never Was a Girl Like You [2] Ain't You Glad You Found Me [2] I'm Afraid To Come Home In the Dark [2] I Used to Be Afraid to Come Home in the Dark [2] 'Neath the Old Cherry Tree, Sweet Marie [2] Not Yet, But Soon: Musical [2] Nurse Girls and Doctors I'm Wise I'm The Leading Lady Wonderland Those are Things that Happen Every Day San Antonio O, Come My Lou Mary Wise The Wedding of the Blue and Grey 1908

Ivanhoe [w/Butler]Don't Forget to Drop a Line to Mother [2] Dat Friend of Mine [2] I Want Someone to Call Me Dearie [2] They'll All Be Waiting for You at the Train [2] We Two in an Aeroplane [2] Water Never Did That [2] I Was a Hero Too [2] Rebecca [2] My Lady Bug [2] I'd Rather Be a Lemon Than a Grape Fruit [2] That's Politics [2] Maybelle: Waltzes Sahara (My Sweet Sahara Jane) [2] Perfectly Terrible Dear [2] I Wonder What's the Matter With My Eyes [2] You'll Never Miss the Water Till the Well Runs Dry [2] My Rosy Rambler [2] You Want Someone to Love You [2] Song of the Waiters [2] It Looks Like A Big Night To-Night [2] A Broken Idol: Musical [2] Cured A Little China Doll Marie Love Makes the World Go Round (That's the) Sign of the Honeymoon Bobbing Up and Down Poor Old Dad's in New York for the Summer Have a Drink To Yankee Land Alabama 1909

Golden Arrow (Intermezzo)Golden Arrow (Song) [2] Sunbeam [2] A Little Flat in a Great Big Town [2] A Terrible Turk: Two Step Forget Me Not [2] Heinze [2] Heinze is Pickled Again [2] 'Liza [2] He Was a Cowboy [2] Then We'll All Go Home [2] Bonnie Annie Laurie [2] Honey Rag I Want Somebody to Play With [2] I've Lost My Gal [2] Go Back [2] Love Light [2] 1910

Cavalier Rustican' Rag [2]Every Heart Must Have Its Sorrow [2] Dance of the Whip-poor-will Miami: A Souther Idyll Meet Me Down by the River, Dearie [2] Going Up [2] Now She's Anybody's Girlie [2] I'd Like to Tell Your Fortune, Dearie [2] He Got Right Up on the Wagon [2] I'm Just Pinin' For You [2] The Girlies Santa Fe [2] What's the Matter with Father? [2] Play That Wedding March Backwards [2] Who Are You With To-Night? [2] Odds and Ends Girlies: Musical [2] Going Up in My Aeroplane That's Good You Can Find It in the Papers Every Day Who Were You With To-night The Bull Frog and the Dove Why Be a Hero? Ring Me Up in the Morning Baby Talk Concerina Rowing Song Honolulu Rag (aka Honolula Rag) 1911

Down In The Old Meadow Lane [2]Father's Allowed to See Us Twice a Year [2] Do It Now [2] Shoes and Socks Shock Susan [2] Injun Love [2] [w/John L. Golden] Under the Pretzel Bough [2] I've Been a Good Santa Claus for You [2] The Pierrot Dance [2] The Raggity Man [2] |

1911 (Cont)

Good Night Ladies [2]Lazy [2] Oh That Navajo Rag [2] Naughty, Naughty, Naughty [2] When I Was Twenty-One and You Were Sweet Sixteen [2] The Hair Of the Dog [w/W. Kendall] Forever With You in My Dreams [3] Casey [3] Let Me Build a Home for You [3] 1912

I'm Goin' Back to Oklahoma [2]Roo-Te-Too-Toot [2] I Like It Better Every Day [2] The Raggedy Man [2] That Slippery Slide Trombone [2] I Want Some One [2] Oh You May [2] You Wouldn't Know the Old Place Now [2] My Hat's In the Ring [2] Beautiful Lady: Waltz Piccolo Jamaica Jinjer Ladies! Ladies! [4] Little Girls Beware (of the Sirens) [4] Mon Bijou [4] Do You Think You'll Call Again? [w/Jack Mahoney] Honey Mine [5] The Hold Up Rag [5] Frisco Dan [6] That Old Girl of Mine [6] Is There Anything Else I Can Do For You? [6] 1913

That Devil Rag [5]Oh! You Lovable Chile [6] You're the Girl [6] You're the Sweetest Rose that Grows in Old Killarney [6] In June [7] I'm in Love With the Mother of My Best Girl [7] Sunshine and Roses [7] I'm Getting Used to It [w/Harry B. Lester] 1914

Evening: ReverieTangomania That Sneaky, Creepy Tune Cheese And Crackers Just a Moment (Valse Hesitation) Wrap Me in a Bundle and Take Me Home With You [7] Blarney [7] Back, Back, Back to Indiana [7] In Old Missouri [7] On the Road to Mexico Through Dixieland [8] Way Down on Tampa Bay [9] Don't You Dare to Call Me Up at Home [9] When I Was A Dreamer And You Were My Dream [w/Roger Lewis/George A. Little] I'm Going to Make You Love Me [9] 1915

Oh, My!Come On Along Rubenstein (Instrumental) Rubenstein [w/Philip Braham] Oh My!: One Step Memories [7] Same Old Summer Moon [7] On the Trail to Santa Fe [7] My Tom Tom Man [7] Untold: Ballad [10] Love Comes A-Stealing [7] Ypsilanti (Yip-si-lan-ti) [10] I Love to Tango With My Tea [10] I Want a Little Love From You [8] 1916

My Dreamy China Lady [7]Just a Word of Sympathy [7] Where the Shamrock Grows [w/J.B. Walsh] I'm Looking for a Girl Like Mother [7] I Love My Mother-In-Law [9] Pretty Baby [11,7] Whose Pretty Baby Are You Now? [7] Sweethearts [7] You Made the World for Me [w/Bessie Buchanan] Love, Honor and Obey [w/J.P. McEvoy] 1917

I've Been Fiddle-ing [11,7]Because You're Irish [7] If We Can Be Together [7] On the Road to Home Sweet Home [7] Rock-A-Bye Land [7] Hula Serenade (Sweet Dreams) [7] Play That Hula Waltz For Me Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay [7] Alabama Moon [8] So Long, Mother [7,12] China Dreams [12] 1918

Kaiser Bill [12]Just 'Round the Corner [7] Afterwhile [w/Thomas Bowers] When We Went to Sunday School [7] Put Your Hands in Your Pockets and Give, Give, Give [7] For Your Boy and My Boy, Buy Bonds! Buy Bonds! [7] Tell the Folks in Dixie I'll Be Back There Some Day [7] For the Boys Over There [7] I Can't Get Along Without You [7] It Must Be Love [7] It Might As Well Be You [7] What Are You Going To Do To Help the Boys? [7] You're in Style When You're Wearing a Smile [w/Al Brown] [7] We'll Build a Rainbow in the Sky [w/Richard A. Whiting] When We Meet in the Sweet Bye and Bye [w/Stanley Murphy] 1919

My Choc'late Soldier Sammy BoyMississippi Shore [w/Arthur Sizemore] (Such a) Baby [7] I'll Wait for You [7] That's the Way That I've Missed You [7] In Springtime [13] Your Eyes Have Told Me So [7,14] Some Quiet Afternoon [7] 1920

Dreamy Paradise [13]Some Little Bird [15] [w/Lindsey McPhail] Dreaming of the Same Old Girl [7] Sweetie o' Mine [15] Don't Be Cross With Me [15] 1921

Old Kentucky MoonlightHoney, (Dat's All) 1922

I'm Just a Little Blue (For You) [15]1923

Tweet Tweet [15]Nearer and Dearer [15] The Girl Of The Olden West [15] Skeezix [w/Louise Fields] [15] You Can't Make a Fool Out of Me [w/Paul Cunningham] 1924

Sing Me "Oh, Solo Mio" [7]Dreams [w/James LaMont] In the Hills of Old Virginia [15] Old Pal [7] Until Tomorrow (Hasta Manana) [15] [w/Al Hegbom] 1925

Drifting and Dreaming (Sweet Paradise)[13,15,16] Alabamy Cradle Song [w/Arthur Otis] [15] Kentucky's Way of Sayin' Good Mornin' [7] 1926

With Mother a Smilin' on Me [12]The Moonlight Trail [12] 1927

What Could I Do? [7]Surrender [w/Jeff Edmonds] [15] Blue Ridge Moon [15,17] 1928

Nita: A Spanish Love Song [18]Swingin' Along with Lindy [7] Toy Town [w/Charles L. Cooke] 1930

My Prayer for Today [17]1931

Don't Lay Me on My Back in My LastSleep [17] A Moonlight Memory [7] The Little Old Church in the Valley [15,17] Beautiful Love [15] [w/Victor Young & Wayne King] 1932

Calling Me Homeward To You [18]Dearest [18] 1933

When the Sun Comes Tumbling Down [17]Softly Steals the Night [15] Your Chicago, My Chicago [17] 1934

When You and I Were School DaySweethearts [17] Golden Sands and Silv'ry Sea [14] 1936

Dancing Toys [w/Ted Weems]1937

Enchanted Moon [14]Unknown

Dance of the KewpiesI Wish I Wuz A Kid Again Lover's Lane Waltz

1. w/Paul B. Armstrong

2. w/Harry Williams 3. w/Arthur Gillsepie 4. w/Herbert Thompson 5. w/Edward Madden 6. w/Earle C. Jones 7. w/Gustave Kahn 8. w/J. Will Callahan 9. w/A. Seymour Brown 10. w/Alfred Bryan 11. w/Tony Jackson 12. w/Raymond Egan 13. Erwin R. Schmidt 14. w/Walter Blaufuss 15. w/Haven Gillespie 16. w/Loyal Curtis 17. w/Gene Arnold 18. w/Walter Hirsch |

Selected Rollography Selected Rollography | |

|

Piccolo

Evening Reverie Dance of the Kewpies Every Heart Must Have Its Sorrow The Holdup Rag Jamaica Jinjer Oh My: One Step Havana: Argentine Just a Moment: Waltz Come On Along Cheese and Crackers Sunshine and Roses That Sneaky, Creepy Tune Love Comes A-Stealing On the Trail to Santa Fe Oh That Navajo Rag Way Down on Tampa Bay Tangomania The Hummingbird Sweethearts |

[QRS 80448]

[QRS 80535] [QRS 80586] [QRS 80592] [QRS Autograph 100036] [QRS Autograph 100038] [QRS Autograph 100098] [QRS Autograph 100104] [QRS Autograph 100105] [QRS Autograph 100260] [QRS Autograph 100261] [QRS Autograph 200274] [QRS Autograph 200284] [QRS Autograph 200401] [QRS Autograph 200402] [QRS ?] [QRS ?] [QRS ?] [QRS Artecho R-3013] [Aeolian ?] |

One of the more prolific composers of not just the ragtime era but beyond, came from rather humble beginnings in Marengo Illinois, just west of Chicago. He was Born in 1878 (often incorrectly attributed as 1882) to Charles Van Alstyne and Emma May Rogers, descendants of Dutch immigrants. The family was shown residing in nearby Riley in 1880, a rural town just south of the somewhat larger Marengo. Egbert took to the keys at an early age, and was playing the organ at the Marengo United Methodist Church by the time he was seven, which is also when his father died. Charles had been the superintendent of the Sunday School at the church, and Egbert's grandfather was the minister of the congregation.

His formal classical training came from Miss Carolyn Coon, daughter of the town's founder. He was later honored with him in 1951 when Egbert was 72 and Miss Coons was 92, and still at work for the phone company. When he was of high school age, Egbert completed his secondary education in Chicago, while also attending the Chicago Musical College (later incorporated into Roosevelt University) thanks to a scholarship. Further piano studies were pursued through a scholarship at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. He often returned to Marengo where he played concerts at various venues there.

When he was of high school age, Egbert completed his secondary education in Chicago, while also attending the Chicago Musical College (later incorporated into Roosevelt University) thanks to a scholarship. Further piano studies were pursued through a scholarship at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. He often returned to Marengo where he played concerts at various venues there.

When he was of high school age, Egbert completed his secondary education in Chicago, while also attending the Chicago Musical College (later incorporated into Roosevelt University) thanks to a scholarship. Further piano studies were pursued through a scholarship at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. He often returned to Marengo where he played concerts at various venues there.

When he was of high school age, Egbert completed his secondary education in Chicago, while also attending the Chicago Musical College (later incorporated into Roosevelt University) thanks to a scholarship. Further piano studies were pursued through a scholarship at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. He often returned to Marengo where he played concerts at various venues there.By the time he was eighteen, Bert, as he was often known, took to the road touring the vaudeville circuit throughout the west. This was interspersed with periods back home where he turned out to be an effective organ salesman, given how well he was able to demo the instruments in people's homes. He also dabbled in composition, having a few of his earliest works published, mostly marches and waltzes. While he was not yet writing ragtime, music that was incongruent with his religious upbringing (as was his lifestyle in later years), he did perform the music, sometimes simply because he needed the money. In 1895 Bert was married to concert hall singer Lucile Trenholme. By the time of the 1900 enumeration the couple had moved to Chicago where Egbert appeared in that census as a musician, and Lucile's widowed mother, Emma Trenholme, was shown as residing with them.

It was also during this time he met up with Harry Williams, an aspiring lyricist. They teamed up on the circuit as what Williams later termed "a pair of near comedians attached to a punk little, almost funny, fly by night snap around 'Box and Cox' company that was trying to earn just cakes by touring the South and Southwest." It was in that troupe that around 1898 Van Alstyne could have readily been killed by a local gag gone wrong. This story, which displays some of Egbert's careless bravado of the time, was relayed to the New York Sun in by Williams in January of 1908:

We played in a hall over a hardware store [in Dardanelle, Arkansas], and there was a dance scheduled to follow the performance. It leaked out that Van Alstyne was a piano thumper of skill, and so the main noise of the dance asked him to chop the keys for the dancers. There were five bucks in it for Van — more honest Injun money that he'd seen in nine rains — and he jumped at the chance.

Van Alstyne's low comedy part in the show was a small bit. but it gave him a chance to squeeze out just one big laugh — and at that time Van, being some young and vealy, would rather have got that laugh out of 'em than sit down to a large bland meal, and meals weren't so dead bland or frequent right then at that. He got his laugh in his small bit by an allusion to the local souse. Upon his entrance in a grotesque rummy's rig somebody on the stage asked him who he was, and then he came out with the name of town's leading drunk. It was a gag that had always gone well.

Van had to depend, of course, upon somebody around the theatres of the small towns to furnish him with the names of these township rumdums, and up to the Dardanelle blow in he'd invariably been tipped off right about the local drunks. At Dardanelle, however, he stacked up against one of these country humorists or something. Before making up Van asked this fellow the name of Dardanelle's leading suds artist. "Fellow by the name of Cunningham," the house mechanician told him, and of course that sounded right and normal.

The show went all right, getting its share of shrieks and things, up to the minute that Van Alstyne nudged in and got off his line about the presumable town drunk. "Me? Why, I'm Cunningham," Van got off in reply to the usual question following his entrance — and then there was a dead, dead, horrible silence. Van, who had his head turned toward the audience waiting for the usual howl, allowed his jaw to drop so when that silence came I was afraid it was going to thud on the stage. You never heard such a white frost following a scream line in all your born days. You could hear the little icicles forming and dropping tinklingly from the rafters...

The show went all right, getting its share of shrieks and things, up to the minute that Van Alstyne nudged in and got off his line about the presumable town drunk. "Me? Why, I'm Cunningham," Van got off in reply to the usual question following his entrance — and then there was a dead, dead, horrible silence. Van, who had his head turned toward the audience waiting for the usual howl, allowed his jaw to drop so when that silence came I was afraid it was going to thud on the stage. You never heard such a white frost following a scream line in all your born days. You could hear the little icicles forming and dropping tinklingly from the rafters...When the show was about over, however, the manager came back, and he was the solemn looking mug. "Who's this Cunningham bug that I was steered onto?" Van asked the manager. "Oh. nobody," replied the manager, "except the worst man in Arkansas, that's all! He's a gun and knife man from the Ozarks and beyond, and he isn't much of a rummy at that. Mainly he's just bad, and bad all over, and whoever it was told you to use his name in that line handed you a ripe one."

Van asked if Cunningham was in the house when the crack had been got off. "No," replied the local manager, "but he'll hear about it. They're some on the talk in this here happy valley."

Well, we were all considerably worried about the thing, but we decided to make the best of it and try to forget it. That's the way Van looked at it, anyhow. He had that engagement to whack the piano for the dancers after the show, and the five bones he was to get for the job looked as big as a shifted sandbar to him, and in the business of stripping off his makeup and getting ready to step down to the piano in the hall he forgot about Cunningham.

I didn't, though. After shedding my funny clothes I walked through the body of the house and then downstairs, with the idea of sort of rubbering around to hear what I could hear in connection with Van's use of the bad man's name. The dancing bunch were already arriving when I got out front, and a lot of the local sports were hanging around the one entrance watching the Dardanelle girls flock along in their pretties. Presently a huge, gaunt chap nudged up out of the darkness and they addressed him as Cunningham. Then I heard some talk that made my knees wabble around as if I had some of that ataxia.

They were saying to the gaunt one that it would be a shame to plug up the piano thumper until after the dance, that he was the only key rapper available in the town of Dardanelle that night, that the girls had set their hearts on the dance and that the musicker could just as well be lead pelted after he'd got through with his job at the piano.

"All right," I heard Cunningham growl in reply to that stuff, "but I'll get him when he gets through, and I'll get him right!"

...I wouldn't have given two bits for Van Alstyne's clutch on the game of life as I listened to that stuff, and I was so wabbled up that it took me some time to dope out a way to get Van out of the mess. I went back to the hall, climbed up the stairs and then through the crowd of Dardanelle dancers up forward near the stage to where Van Alstyne was playing away at the dance stuff. I leaned over and whispered a few little warning numbers to him. I told him what was coming off, while the little round globules of perspiration spirted out of his forehead and his eyes bulged. But he went right on playing gamely enough, and I told him of the little way I had framed whereby I thought maybe he could be saved for a future generation. Oh, he went right on playing after I'd left him, but the music had a Chinese sound to me after I'd told him those things, although nobody else in the dancing crowd seemed to notice it.

I scampered back to the dark stage, lit a couple of candles that I dug out and looked around for ropes. I let one out of a back window, and when he got a chance to leave the piano Van slid down it. After that I kited out of the hall down the front way, where the pizen Cunningham and his bunch still were standing gloomily around, waiting for the windup of the dance and the appearance of Van Alstyne.

I joined Van Alstyne at the hotel a minute or so later, and together we beat it down to the station in time to nail a local that would carry us to our next stop - quite a hike ahead. The rest of the company, leaving Dardanelle at daylight, caught up with us in the afternoon, and they told us that Cunningham had been in all kinds of a horrible rage when Van Alstyne got away from him and had stormed into the Dardanelle Hotel and heisted all of the other troupers out of their beds and lined them up in the hall to see if the man he wanted was among them.

That was some cure for Van Alstyne and all the rest of that little layout of troupers as to the local gag thing. Van cut that line out altogether and built up another laugh for himself, and although that was ten years ago I've never heard him get real funny in alluding to the kinks of other people since that same nervous night in Dardanelle. Ark.

During their time on the road evading starvation and angry gunslingers, the two worked up a few songs, as well as the courage to eventually quit the circuit and migrate to New York. They settled there in 1901 to break into the songwriting business in what would soon be known as Tin Pan Alley. The pair also took local vaudeville gigs, usually performing their own songs on stage. Fortunately, Bert's pianistic talents kept him employed while they were waiting for their break, often as a song plugger for various publishing houses and outlets, working mostly for Shapiro and Remick (when the two still shared a firm).

They settled there in 1901 to break into the songwriting business in what would soon be known as Tin Pan Alley. The pair also took local vaudeville gigs, usually performing their own songs on stage. Fortunately, Bert's pianistic talents kept him employed while they were waiting for their break, often as a song plugger for various publishing houses and outlets, working mostly for Shapiro and Remick (when the two still shared a firm).

They settled there in 1901 to break into the songwriting business in what would soon be known as Tin Pan Alley. The pair also took local vaudeville gigs, usually performing their own songs on stage. Fortunately, Bert's pianistic talents kept him employed while they were waiting for their break, often as a song plugger for various publishing houses and outlets, working mostly for Shapiro and Remick (when the two still shared a firm).

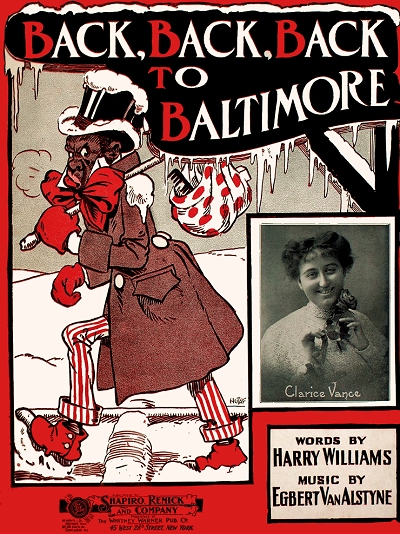

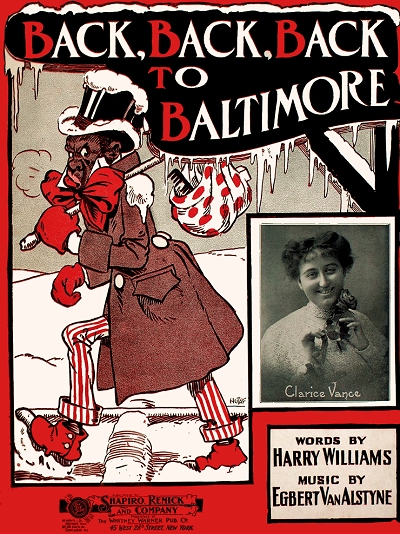

They settled there in 1901 to break into the songwriting business in what would soon be known as Tin Pan Alley. The pair also took local vaudeville gigs, usually performing their own songs on stage. Fortunately, Bert's pianistic talents kept him employed while they were waiting for their break, often as a song plugger for various publishing houses and outlets, working mostly for Shapiro and Remick (when the two still shared a firm).The break they boys were waiting for came in 1903 with the interpolation of Navajo into the stage musical Nancy Brown, as performed by its famous star, Marie Cahill. Its success led to an association with Jerome H. Remick, one of the most prolific publishers of the ragtime era, where they would remain together through at least 1911. Between their collaborative talents and Remick's wide distribution and marketing network, Van Alstyne and Williams became the golden boys of popular song, turning out waltz tunes, intermezzos, comic songs, and an inordinate number of ballads. Their next big hit was Back, Back, Back to Baltimore, followed by the Atlantic City referenced Why Don't You Try? (The Rolling Chair Song).

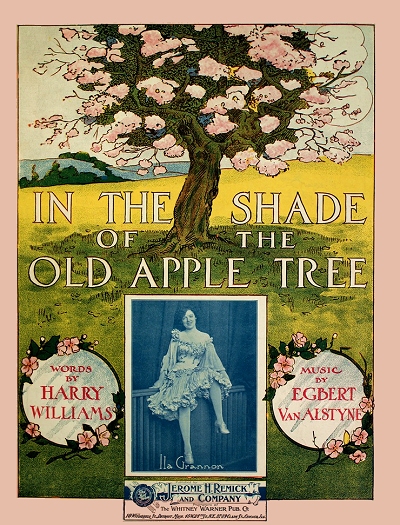

Of the team's big hits, In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree (1905) has remained their most enduring work. Van Alstyne's inspiration for the lyrical waltz song was as simple as a longing for his childhood home in Marengo while he was lonely and broke in New York City. Other tunes like the comical I'm Afraid to Come Home in the Dark (1907) and a follow up to that song also enhanced their growing reputation. It was the combination of Van Alstyne's very hummable and simple melodies and William's lyric poetry that helped keep them popular for so long. Williams was humble and non-assuming in the press, and as early as 1908 was crediting Egbert for their quick rise to fame as composers.

It is well-known that fame, particularly in the entertainment world, can have adverse effects on many performers, which although they do not always adversely affect the quality of their work or output, they can create problems in their relationships with others. Van Alstyne suffered from this to a degree, becoming a womanizer, heavy drinker and smoker, and later a hypochondriac to some degree (understandable, given these vices).

This behavior was underscored to a degree when in 1904 he left Lucile and eloped on July 21 to Waukegan, Wisconsin, with vaudeville actress Louise Henry (King), who had been promoting his songs on stage. She was the daughter of Winchester, Virginia newspaper owner George R. Henry, and had previously been married to her manager, Joe King. The couple was based in upstate New York for a while as they toured the circuit. Trouble was reported as early as December, 1905, in the Albany Evening Journal: "Mr. and Mrs. Egbert Van Alstyne have forgotten their domestic differences and have gone South on a second honeymoon. They had separated after a quarrel and divorce proceedings had been instituted... His wife is an actress and when she heard one of her husband's new love songs she knew that he was thinking of her. That accounts for the reconciliation." Still, their union did not last very long, and the couple divorced in June 1907. The reason should be clear when it is considered that Egbert wasted no time and got married the day of or day after his second divorce, as this story from the June 29, 1907 Chicago Tribune explains:

EGBERT A. VAN ALSTYNE WEDS DRAMATIC READER

An automobile ride, a long walk in a dusty country road, and a journey in a prosaic railway coach were necessary before the elopement of Mabel Carolyn Church, a dramatic reader, and Egbert A. Van Alstyne, a song writer, became an accomplished fact yesterday. The couple were married in Kenosha, Wis., at 10 o'clock in the morning by the Rev. W. W. Stevens, pastor of the Park Avenue Methodist church, in the parlors of the Eichelman hotel.

Miss Church, who gave her address as 240 Ohio street, started with Mr. Van Alstyne, two of her women friends, who said their name was Brown and Samuel Siegel at 7 o'clock in the morning. They started for Kenosha in Mr. Van Alstyne's auto, but the machine broke down a couple of miles south of Fort Sheridan. For forty-five minutes the men of the party worked in an effort to start it again. Then the bride to be became impatient.

"Why Don't You Try?"

"I started out to get married this morning, and we mustn't let this stop us," she announced.

Then she hummed "Why Don't You Try?" which brought Mr. Van Alstyne many shekels, and the automobile was abandoned to its fate. The entire party set out on foot and walked into Fort Sheridan, where they took a train for Kenosha.

But the troubles of the song writer and the reader still were far from ended. Unless you get a court order you cannot get married in Kenosha until one has given five days' notice of one's intentions. But Miss Church kept up her spirits to the tune of "Why Don't You Try?" and Judge Slosson granted the order when he heard her hard luck story.

While Bert's antics and infractions eventually took a toll on the team, Van Alstyne and Williams contributed occasional songs to musicals and also make an effort to write some of their own shows for the theater from 1907 to 1910. An early one was Not Yet, But Soon from 1907 which ran only 8 performances. Another show was A Broken Idol, copyrighted late in 1908, which ran just 40 performances in late summer 1909. This was followed by Girlies in 1910 which clocked a more respectable 88 performances. While these turned out some mildly memorable tunes, the shows themselves did not last very long, perhaps putting a strain on the relationship of Bert and Harry. Things between them started to really sour in 1910, and by early 1912, after having composed more than 160 tunes together, they were no longer a team, Williams citing his desire to pursue an acting career as a factor for the breakup. A few of their previously submitted songs were published during this time given how Remick paced their output.

Bert wrote a few instrumental pieces from 1909 through the mid-1910s, something he rarely did during the partnership with Williams, during which the exceptional Honey Rag (1909) had appeared. Now he focused on rags in the form of dance music, and a couple of waltzes. Williams and Van Alstyne piano rolls started appearing frequently in 1907, particularly on the General Music Supply Company Standard Rolls line. Bert also cut the first set of a number of piano rolls of his music for QRS and continued playing occasional rolls into the 1920s. He then turned to lyricist Earle Jones among others and turned out a few songs, before discovering his next long-term partner, the prolific Gustave Kahn, better known as Gus, around 1912.

During the remainder of 1910s and through part of the 1920s, Van Alstyne and Kahn turned out a new set of somewhat consistent hits, around 50 songs in total, although Bert's work with Gus never reached the level of popularity as it had with Williams. Even though some of their later pieces were quite frankly jazz, Van Alstyne made it clear that he was an old-fashioned ballad writer for the most part, and disdained jazz music, publicly stating so in a 1922 symposium. He also teamed up with some other lyricists that would become better known in teams of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of his instrumental pieces, or instrumental arrangements of his songs, were handled by the well-known composer and arranger of the silent movie era, J. Bodewalt Lampe. Another arranger of Bert's works was Les Copeland. Given how arrangers put their stamp on tunes as well, these could be considered indirect collaborations of the two writers in each case. Egbert joined ASCAP in 1923, nearly a decade after it was founded by many of his peers.

Even though some of their later pieces were quite frankly jazz, Van Alstyne made it clear that he was an old-fashioned ballad writer for the most part, and disdained jazz music, publicly stating so in a 1922 symposium. He also teamed up with some other lyricists that would become better known in teams of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of his instrumental pieces, or instrumental arrangements of his songs, were handled by the well-known composer and arranger of the silent movie era, J. Bodewalt Lampe. Another arranger of Bert's works was Les Copeland. Given how arrangers put their stamp on tunes as well, these could be considered indirect collaborations of the two writers in each case. Egbert joined ASCAP in 1923, nearly a decade after it was founded by many of his peers.

Even though some of their later pieces were quite frankly jazz, Van Alstyne made it clear that he was an old-fashioned ballad writer for the most part, and disdained jazz music, publicly stating so in a 1922 symposium. He also teamed up with some other lyricists that would become better known in teams of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of his instrumental pieces, or instrumental arrangements of his songs, were handled by the well-known composer and arranger of the silent movie era, J. Bodewalt Lampe. Another arranger of Bert's works was Les Copeland. Given how arrangers put their stamp on tunes as well, these could be considered indirect collaborations of the two writers in each case. Egbert joined ASCAP in 1923, nearly a decade after it was founded by many of his peers.

Even though some of their later pieces were quite frankly jazz, Van Alstyne made it clear that he was an old-fashioned ballad writer for the most part, and disdained jazz music, publicly stating so in a 1922 symposium. He also teamed up with some other lyricists that would become better known in teams of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of his instrumental pieces, or instrumental arrangements of his songs, were handled by the well-known composer and arranger of the silent movie era, J. Bodewalt Lampe. Another arranger of Bert's works was Les Copeland. Given how arrangers put their stamp on tunes as well, these could be considered indirect collaborations of the two writers in each case. Egbert joined ASCAP in 1923, nearly a decade after it was founded by many of his peers.While Van Alstyne and Kahn were still partners, Bert was promoted to the position of Chicago manager of the Remick company. Among the team's duties for Remick was to scout out new songwriting talent, or at least procure good tunes. One of these became one of the most unnecessarily controversial subjects of Bert's life, largely because of misunderstandings on multiple levels, most of which have now been cleared up thanks to the efforts of diligent Van Alstyne historian, Tracy Doyle.

As it turns out, the two heard black Chicago pianist Tony Jackson, who was not the prettiest of men and openly gay to boot [Chicago was rather progressive in this regard], performing a ditty he had written called Pretty Baby. The melody was very charming and instantly attractive to Bert and Gus. However, since it had been written for Jackson's boyfriend, it needed some major modifications to the salacious lyrics in order to be palatable for the Remick catalog. In addition, Van Alstyne added a verse that was adapted from a previous song he had composed. As a result, the original edition offended Jackson supporters since it gave both Kahn and Van Alstyne co-composer credit, which was just the same quite appropriate, given their considerable input into the song. This regrettable miscasting of the situation actually made some musicians hostile to Van Alstyne for most of the rest of his life, something he found to be hurtful. Never mind that subsequent stage performances of the piece made it a big hit for all of the composers, or that Jackson's name appeared above Van Alstyne's on the cover. And while many say that both the composer and his lyrics were compromised, it would be clear now that some of the original lines would have been unsuitable for mass publication. It is clear, however, that Jackson may not have got his share of royalties, having been paid $250 outright for the rights to the tune. In any case, Bert's daughter stated that this misunderstanding haunted him until his death in 1951.

Another question, this time concerning Van Alstyne's originality, was highlighted in the trades in 1917. There was a suit filed over one of Egbert and Gus's tunes, which was eventually overturned in court. According to the Music Trade Review of August 11, 1917:

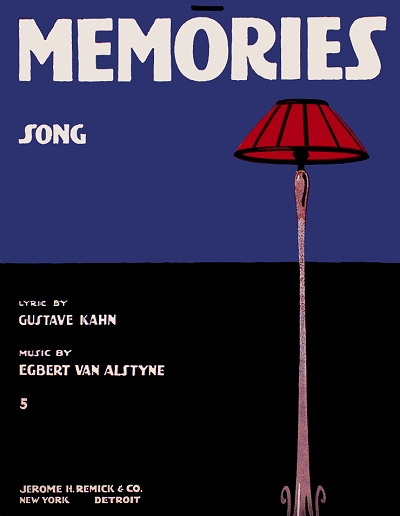

Julius E. Andino, doing business as the Musicians' Music Publishing Co., has brought suit in the United States District Court against Jerome H. Remick & Co., Gustav Kahn and Egbert Van Alstyne, petitioning that the defendants be restrained from selling or further publishing a musical composition entitled "Memories," of which the two latter defendants are authors. The suit also asked for an accounting of receipts and profits of the composition and $8,000 damages.

Andino in his complaint alleges that in 1912 he composed a musical composition entitled "Sleepy Rose," with lyrics by Schuyler Green, and that Green had sold his rights to the song to the Musicians' Music Publishing Co. He further alleges that in October, 1915, Kahn and Van Alstyne with a knowledge of the existence of the plaintiff's composition, wrote the song entitled "Memories," which he claims is not original, but is no less the same musical composition and thought of the composer as the composition entitled "Sleepy Rose," although differently arranged and adapted. He claims that the similarity is so marked that the public find it almost impossible to distinguish between the two songs. The plaintiff also alleges that he advised Remick & Co. of his claims in November, 1916, but that the company continued selling the song.

The complaint also asked that the plates and copies of the song in possession of Remick & Co. be delivered to the court until the action is determined on trial.

Egbert took ill from exhaustion and other maladies in early 1917 and retreated to his farm, bought with the proceeds from In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree, to recover. He was back at work before Spring. Van Alstyne is shown on his 1918 draft registration in Chicago as a composer employed by the Majestic Theater. In the 1920 census Van Alstyne listed himself as a music publisher rather than as a composer, and still living with Mabel and Egbert Jr. in Chicago.

In October 1919, Egbert announced that he resigned from Remick, and was forming his own firm. As stated in the Music Trade Review in mid-November: "Some time ago The Review printed an announcement that Egbert Van Alstyne would shortly enter the music publishing field in his own behalf. He now announces the formation of the firm of Van Alstyne & Curtis, with Chicago professional offices at 117 N. State street, and with a Toledo office under the management of Loyal Curtis, his partner, in the Gardner Building, Toledo, O. Announcement of the New York headquarters will be made shortly..." It was a short-lived effort with few pieces under that imprint from 1919 to 1921. At some point in 1921 Curtis took over the company under his own name.

His works with Remick continued to appear throughout the 1920s, with a couple of entries in the catalog of Sam Fox in Cleveland, Ohio. Egbert also did a vaudeville tour in the early 1920s, appearing everywhere from Indianapolis to Buffalo, where he was reportedly warmly greeted by appreciative audiences. In most instances he played his songs solo or with a trio, accompanied by a tenor, one of his popular choices being Clem Dacey. Most of these performances were in support of his Remick catalog, now that his own firm had folded. Some were heard on early radio broadcasts.

Egbert's attitude on modern music was clear in occasional interviews. One published in the Daily Northwestern in Oshkosh, Wisconsin on May 25, 1927, includes the following snippets:

"I don't like jazz," he says, "and I'm purely a ballad writer, for that type of song appeals to me. I don't dislike jazz, and I don't think that it will ever die out. It is just as popular today as it ever was, and there are more jazz bands throughout the country than ever before... Old songs seem to live longer than the popular jazz numbers..."

"A song becomes popular over night, with the radio and jazz bands, but it is forgotten in a few months. Ballads sell much better and live much longer. 'In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree' is one of the few songs that has lived nearly 25 years. Ernest Ball's 'Mother Machree' and 'Till the Sands of the Desert Grow Cold' are my type of song. Melody writing is an art in itself. These ballad types also have the support of the music teachers and the conventions, who are always seeking the better kind of songs."

It is Van Alstyne's wish that he may be able to keep on writing ballads until he is 96. "It has always been my aspiration to write ballads as long as I live," he asserts.

Things changed in Bert's life over the ensuing decade, and some details are uncertain concerning his home life. The 1930 enumeration showed Egbert as a lodger, still evidently legally married, but Mabel and Egbert Jr. were not listed at the same address. Their son was in St. Louis attending college that year. Claiming a desertion that began as early as November 1920, Mabel legally divorced Bert in December 1930, receiving their 280 acre Michigan farm and other real-estate. She died in December, 1937, having never remarried. Bert, however, did remarry in 1931 to Miss Ruth Leslie, nearly three decades his junior. He had met Ruth when she was a seven year old singer in the local theaters, and had hired her to plug his songs for publishers.

Egbert had reverted back to the status of songwriter by this time, although his actual output was somewhat scant from 1925 on. There were offers for him to move to Hollywood or New York to continue his career, but he rebuffed all of them. Composing a few pieces into the 1930s, many of them for the movies, and a few of them rare collaborations with other music writers as well, Van Alstyne finally seemed to disappear from view after 1935 or so, with only piece appearing after that time. His mother received some recognition at age 85 in 1941 as the oldest working radio artist, under the name of Aunt Em, which she had done as a singer and storyteller throughout the 1930s.

As of the 1940 enumeration Egbert and Ruth were living in the same Chicago home as in 1930, and he claimed to be working as a pianist for the motion picture industry. Whether this was for Chicago's fledging efforts at film studios or working for the Hollywood studios is unclear. Not too much came of it, and he was mostly retired by the mid-1940s. Then Egbert was "rediscovered" in the very late 1940s about the time that the country was experiencing a resurgence of nostalgia for the ragtime era given the recordings from Capitol Records and the publication of the first edition of They All Played Ragtime. Between 1947 and 1950 Egbert was the guest at many public events and on radio shows featuring his now nostalgic tunes. The 1950 census, taken in Chicago, showed Egbert and Ruth with no occupation.

Ragtime performer and entrepreneur Bob Darch, who befriended composers like Van Alstyne and Percy Wenrich in their later years, recalled August 19, 1950, the day that Bert was honored at the 21st Annual Chicagoland Music Festival held at Soldier Field (following a ceremonial dinner held the previous evening). It included the display of a ceremonial apple tree from his home town of Marengo, along with many town residents in attendance, and a band played the famed Old Apple Tree number (which was also a fixture in a scene of The Wizard of Oz from 1939) while he rode through the field in a convertible. Bob said that it brought genuine tears of joys to the old man's eyes, largely for the recognition of what he thought had been a forgotten life. Also feted that day was the well-known conductor Henry Weber.

The composer suffered a stroke in April, 1951 while in Miami, and he was brought back to Chicago in May in an ambulance. Egbert Van Alstyne died in July and was buried in the Memorial Park Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois. He was hardly forgotten, but had not been properly recognized for his contributions either at that time. This was fixed to some degree when he was inducted into the Songwriter's Hall of Fame in 1970. His widow, Ruth, passed on in May 1971. While not all of his pieces were located for listing here, at least 340 of the 400 or more he is thought to have composed are included.

I would like to add a personal note of thanks and recognition to my colleague Tracy Doyle, whose personal ties to Van Alstyne's and her love of his music have led to the most extensive look at his legacy and his life, which added to my own research on him to a high degree. Most of the remaining information was uncovered by the author in public records, periodicals, newspapers and other contemporary sources.