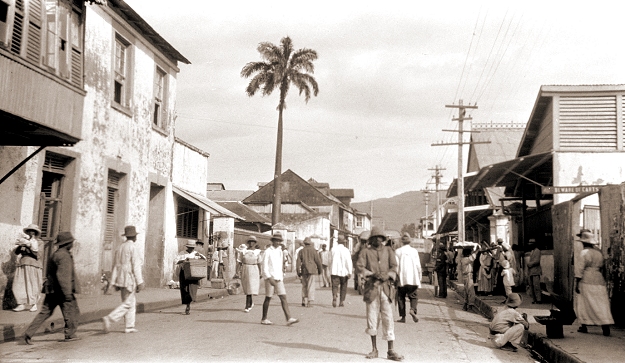

Winifred Atwell (possibly Wenefred at birth) was born in Tunapuna, Trinidad, the most southern island of the West Indies archipelago, to Frederick Monroe Atwell and Sarah Elizabeth Thomas. Her birth year has long been called into question, with 1914 often showing up. However, some official records suggest either 1909 or 1910 as her year of birth, so 1910 will be assumed for this essay. The Atwelss were a family of pharmacists with their own pharmacy just a few miles east of the Port of Spain. This was a discipline in which Winifred was also trained as she grew up.

Sarah got her daughter in front of a piano even before she turned three, and the girl appeared to thrive,

eventually passing all expectations as she quickly learned standard classical works. As with many middle-class Presbyterian families of the East Indies, she also got formal instruction at age four on the instrument, able to play Brahms and Bach by the age of six. According to liner notes on one of her albums, she had given recitals and local concerts at that age, performing pieces by Chopin. Just the same, she knew the family business and dutifully took training in pharmacology as she grew, becoming a qualified druggist. As for her musical life, Winifred starting playing out locally and gained a measure of popularity in various island venues.

|

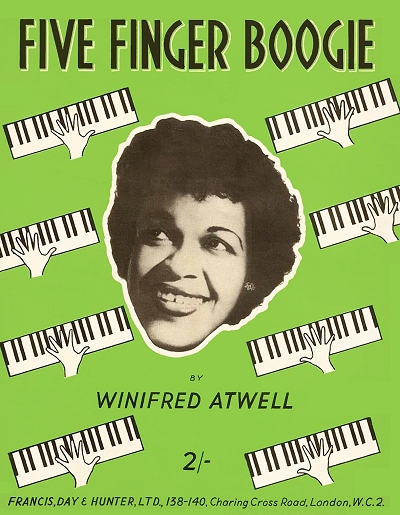

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Atwell played at the Servicemen's Club at the local Royal Air Force Base, located at the airport in Piarco on the north side of the island, less than five miles from Tunapuna. During World War II, it was utilized by both the British Royal Navy Air Force and the United States Army Air Forces. Winifred was kept employed through at least late 1944, and was considered a good source of entertainment at the club. It was there that she was challenged to play something in the increasingly popular boogie-woogie style from the US. Winifred responded with 24 hours by writing a piece she called Piarco Boogie (later known as Five Finger Boogie), and a star was born, in addition to a bet being won. It was also either there or another island venue where a travelling American impresario heard her playing something by Ludwig Von Beethoven, and lauded her talent, giving her the impetus to seek out new pastures, which she did in late 1944.

During World War II, it was utilized by both the British Royal Navy Air Force and the United States Army Air Forces. Winifred was kept employed through at least late 1944, and was considered a good source of entertainment at the club. It was there that she was challenged to play something in the increasingly popular boogie-woogie style from the US. Winifred responded with 24 hours by writing a piece she called Piarco Boogie (later known as Five Finger Boogie), and a star was born, in addition to a bet being won. It was also either there or another island venue where a travelling American impresario heard her playing something by Ludwig Von Beethoven, and lauded her talent, giving her the impetus to seek out new pastures, which she did in late 1944.

During World War II, it was utilized by both the British Royal Navy Air Force and the United States Army Air Forces. Winifred was kept employed through at least late 1944, and was considered a good source of entertainment at the club. It was there that she was challenged to play something in the increasingly popular boogie-woogie style from the US. Winifred responded with 24 hours by writing a piece she called Piarco Boogie (later known as Five Finger Boogie), and a star was born, in addition to a bet being won. It was also either there or another island venue where a travelling American impresario heard her playing something by Ludwig Von Beethoven, and lauded her talent, giving her the impetus to seek out new pastures, which she did in late 1944.

During World War II, it was utilized by both the British Royal Navy Air Force and the United States Army Air Forces. Winifred was kept employed through at least late 1944, and was considered a good source of entertainment at the club. It was there that she was challenged to play something in the increasingly popular boogie-woogie style from the US. Winifred responded with 24 hours by writing a piece she called Piarco Boogie (later known as Five Finger Boogie), and a star was born, in addition to a bet being won. It was also either there or another island venue where a travelling American impresario heard her playing something by Ludwig Von Beethoven, and lauded her talent, giving her the impetus to seek out new pastures, which she did in late 1944.Winifred initially ventured to New York City to study with Russian immigrant pianist Alexander Borovsky. While there, her name made the black-published New York Age on at least two occasions. The first was for her involvement in a concert at The Town Hall in New York on May 10. She was the first artist featured on the program following a presentation by tenor Paul A. Smith of the Altruss Opera Company. Once the war had ended in both the European and Pacific theaters and travel to England was once again secure, Winifred departed for the United Kingdom and new prospects. The New York Age of October 6, 1945, noted that:

Winifred Atwell, noted West Indian pianist, who was heard in recital last season, left last week for England. She can be heard every Tuesday and Thursday over the British Broadcasting Co.

Indeed, some broadcasts from England were available through shortwave or other means, but it is uncertain how many American fans Atwell had accumulated during her months in New York. Once in London she quickly gained entry into the Royal Academy of Music, studying under pianist Harold Craxton, with the hopes of becoming a serious concert pianist. She managed an appearance on early BBC-TV for the show Stars In Your Eyes, and as indicated on the notice of her leaving New York, some radio gigs on the Light Programme, the beginning of frequent broadcasts. Continuing through at least 1947, Winifred managed to become the first female pianist to garner their highest award for musicianship. However, in order to pay for her studies, she also had to work on the other side of the musical aisle, playing popular music, boogie-woogie, and even ragtime in London nightclubs. Later in life she would remember that she "starved in a garret [an attic lodging] to get onto concert stages." In 1947 she was married in Lambeth, London, to white comedian Reginald Edward George Levisohn, with whom she would remain to the end of his life in 1977. Lew would give up his career to manage Winifred.

Continuing through at least 1947, Winifred managed to become the first female pianist to garner their highest award for musicianship. However, in order to pay for her studies, she also had to work on the other side of the musical aisle, playing popular music, boogie-woogie, and even ragtime in London nightclubs. Later in life she would remember that she "starved in a garret [an attic lodging] to get onto concert stages." In 1947 she was married in Lambeth, London, to white comedian Reginald Edward George Levisohn, with whom she would remain to the end of his life in 1977. Lew would give up his career to manage Winifred.

Continuing through at least 1947, Winifred managed to become the first female pianist to garner their highest award for musicianship. However, in order to pay for her studies, she also had to work on the other side of the musical aisle, playing popular music, boogie-woogie, and even ragtime in London nightclubs. Later in life she would remember that she "starved in a garret [an attic lodging] to get onto concert stages." In 1947 she was married in Lambeth, London, to white comedian Reginald Edward George Levisohn, with whom she would remain to the end of his life in 1977. Lew would give up his career to manage Winifred.

Continuing through at least 1947, Winifred managed to become the first female pianist to garner their highest award for musicianship. However, in order to pay for her studies, she also had to work on the other side of the musical aisle, playing popular music, boogie-woogie, and even ragtime in London nightclubs. Later in life she would remember that she "starved in a garret [an attic lodging] to get onto concert stages." In 1947 she was married in Lambeth, London, to white comedian Reginald Edward George Levisohn, with whom she would remain to the end of his life in 1977. Lew would give up his career to manage Winifred.Winifred's big break came in late 1947 when producer Eric Fawcett took a chance on the pianist, engaging her for his production of Sepia starring American singer Adelaide Hall and Brit Edric Connor. She performed Voodoo Moon which turned out to be a program favorite. It was also featured BBC television that October, giving the stars limited national exposure, considering the number sets in households at that time. The following year she experienced the veritable 42nd Street star is born moment, as per producer and impresario Bernard Delfont:

Winifred Atwell first came to us as an accompanist for a singer. Carole Lynne, my wife, was due to sing at a charity concert at the London Casino, but developed a bad throat at the last moment. I rang the theatre to tell them she couldn't appear. I asked Keith Devon, another of my co-directors, if he could replace her and he said: "I've a coloured girl here who played well at rehearsals. Let's give her a chance as a solo act." Winnie did so well we put her under contract.

By "so well," he was referring to the fact that Winifred had to make several curtain calls in response to the vigorous applause after her performance. The way in which she engaged the audience won Atwell a long-term contract with Delfont. After spending some weeks grooming her stage presence and communications with the audience, he placed her into theaters around the UK and Ireland, including a stint at the London Casino. From around 1949 forward, Winifred Atwell found herself headlining several engagements, sharing the bill with top British entertainers, both black and white. There was also more radio on the BBC's Variety Bandbox.

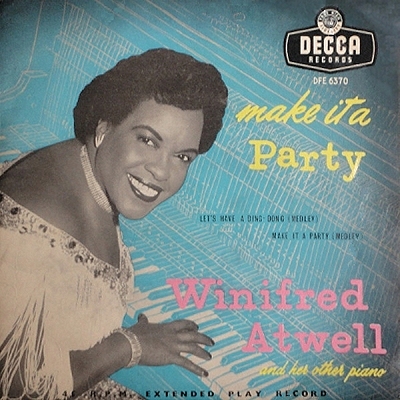

The next logical step was to capture some of Atwell's magic on record. Fortunately for her, this came at a time when not only recording technology was changing, having all but ditched 78-RPM singles for the new multi-band Long-Playing records, recorded on high quality magnetic tape (a combination that began in 1948), but ragtime and honky-tonk tracks were starting to grab hold in both the United States and UK, given the sudden popularity of Lou Busch as Joe "Fingers" Carr, Del Wood and Johnny Maddox. Winifred was introduced to Hugh Mendl, one of the promotion managers at British Decca, known as London Records around much of the world, and he pushed his career forward behind her talent. Despite her talented approach to the ragtime and honky-tonk types of works, Winifred's first 1951 recordings included a single of Manzanilla and The Gypsy Samba. She scored a minor hit with one of the next ones titled Jezebel. It was her subsequent disc, however, that grabbed the attention of her recently-adopted country. On the flip side of a number titled Cross-Hands Boogie, one of her specialties that was expected to be a big number, Atwell laid down a robust rendition of George Botsford's Black and White Rag, which was also gaining popularity with American artists. Something about it engaged the Brits, and in short order she had a number one record, initially selling 30,000 copies in less than two weeks, and eventually getting to over 500,000 on both singles and LPs worldwide. For a time the disc had traction in the US until more American ragtime players dropped their records into the mix.

this came at a time when not only recording technology was changing, having all but ditched 78-RPM singles for the new multi-band Long-Playing records, recorded on high quality magnetic tape (a combination that began in 1948), but ragtime and honky-tonk tracks were starting to grab hold in both the United States and UK, given the sudden popularity of Lou Busch as Joe "Fingers" Carr, Del Wood and Johnny Maddox. Winifred was introduced to Hugh Mendl, one of the promotion managers at British Decca, known as London Records around much of the world, and he pushed his career forward behind her talent. Despite her talented approach to the ragtime and honky-tonk types of works, Winifred's first 1951 recordings included a single of Manzanilla and The Gypsy Samba. She scored a minor hit with one of the next ones titled Jezebel. It was her subsequent disc, however, that grabbed the attention of her recently-adopted country. On the flip side of a number titled Cross-Hands Boogie, one of her specialties that was expected to be a big number, Atwell laid down a robust rendition of George Botsford's Black and White Rag, which was also gaining popularity with American artists. Something about it engaged the Brits, and in short order she had a number one record, initially selling 30,000 copies in less than two weeks, and eventually getting to over 500,000 on both singles and LPs worldwide. For a time the disc had traction in the US until more American ragtime players dropped their records into the mix.

this came at a time when not only recording technology was changing, having all but ditched 78-RPM singles for the new multi-band Long-Playing records, recorded on high quality magnetic tape (a combination that began in 1948), but ragtime and honky-tonk tracks were starting to grab hold in both the United States and UK, given the sudden popularity of Lou Busch as Joe "Fingers" Carr, Del Wood and Johnny Maddox. Winifred was introduced to Hugh Mendl, one of the promotion managers at British Decca, known as London Records around much of the world, and he pushed his career forward behind her talent. Despite her talented approach to the ragtime and honky-tonk types of works, Winifred's first 1951 recordings included a single of Manzanilla and The Gypsy Samba. She scored a minor hit with one of the next ones titled Jezebel. It was her subsequent disc, however, that grabbed the attention of her recently-adopted country. On the flip side of a number titled Cross-Hands Boogie, one of her specialties that was expected to be a big number, Atwell laid down a robust rendition of George Botsford's Black and White Rag, which was also gaining popularity with American artists. Something about it engaged the Brits, and in short order she had a number one record, initially selling 30,000 copies in less than two weeks, and eventually getting to over 500,000 on both singles and LPs worldwide. For a time the disc had traction in the US until more American ragtime players dropped their records into the mix.

this came at a time when not only recording technology was changing, having all but ditched 78-RPM singles for the new multi-band Long-Playing records, recorded on high quality magnetic tape (a combination that began in 1948), but ragtime and honky-tonk tracks were starting to grab hold in both the United States and UK, given the sudden popularity of Lou Busch as Joe "Fingers" Carr, Del Wood and Johnny Maddox. Winifred was introduced to Hugh Mendl, one of the promotion managers at British Decca, known as London Records around much of the world, and he pushed his career forward behind her talent. Despite her talented approach to the ragtime and honky-tonk types of works, Winifred's first 1951 recordings included a single of Manzanilla and The Gypsy Samba. She scored a minor hit with one of the next ones titled Jezebel. It was her subsequent disc, however, that grabbed the attention of her recently-adopted country. On the flip side of a number titled Cross-Hands Boogie, one of her specialties that was expected to be a big number, Atwell laid down a robust rendition of George Botsford's Black and White Rag, which was also gaining popularity with American artists. Something about it engaged the Brits, and in short order she had a number one record, initially selling 30,000 copies in less than two weeks, and eventually getting to over 500,000 on both singles and LPs worldwide. For a time the disc had traction in the US until more American ragtime players dropped their records into the mix.Part of the magic trick of Winifred's recording, in addition to stellar playing, was that rather than using one of the better studio pianos, she and Lew found an old upright in a Battersea junk store (some might call it antique) with a bit of a tinny tone and questionable tune, which they reportedly obtained for a mere 30 to 50 shillings, a bit over $800 in 2023 US dollars. Then, she simply let loose on it with a "take no prisoners" approach, albeit very deftly. Lew apparently thought of this idea of having her perform pop and classics on a concert grand piano, then have the upright rolled out for the honky-tonk portion of her show. This quickly became known somewhat famously as Winifred's "other" piano, as indicated on the Black and White Rag record label. (When the Atwells moved from Great Britain later in life, the "other" piano remained in the UK with British songwriter Richard Stilgoe.)

with a bit of a tinny tone and questionable tune, which they reportedly obtained for a mere 30 to 50 shillings, a bit over $800 in 2023 US dollars. Then, she simply let loose on it with a "take no prisoners" approach, albeit very deftly. Lew apparently thought of this idea of having her perform pop and classics on a concert grand piano, then have the upright rolled out for the honky-tonk portion of her show. This quickly became known somewhat famously as Winifred's "other" piano, as indicated on the Black and White Rag record label. (When the Atwells moved from Great Britain later in life, the "other" piano remained in the UK with British songwriter Richard Stilgoe.)

with a bit of a tinny tone and questionable tune, which they reportedly obtained for a mere 30 to 50 shillings, a bit over $800 in 2023 US dollars. Then, she simply let loose on it with a "take no prisoners" approach, albeit very deftly. Lew apparently thought of this idea of having her perform pop and classics on a concert grand piano, then have the upright rolled out for the honky-tonk portion of her show. This quickly became known somewhat famously as Winifred's "other" piano, as indicated on the Black and White Rag record label. (When the Atwells moved from Great Britain later in life, the "other" piano remained in the UK with British songwriter Richard Stilgoe.)

with a bit of a tinny tone and questionable tune, which they reportedly obtained for a mere 30 to 50 shillings, a bit over $800 in 2023 US dollars. Then, she simply let loose on it with a "take no prisoners" approach, albeit very deftly. Lew apparently thought of this idea of having her perform pop and classics on a concert grand piano, then have the upright rolled out for the honky-tonk portion of her show. This quickly became known somewhat famously as Winifred's "other" piano, as indicated on the Black and White Rag record label. (When the Atwells moved from Great Britain later in life, the "other" piano remained in the UK with British songwriter Richard Stilgoe.)Nearly overnight, and now in her early forties, Winifred's weekly take increased exponentially from her skimpy few pounds at a time in 1947 to several thousand weekly in 1952. British Decca signed her to a long-term contract, and she would cut records for them until at least 1963, albeit a few of them were released on the Pye label in 1962. Some of her early singles sold as many as 30,000 units each week. Whether or not it was a publicity stunt is unclear (and similar ploys have been undertaken by many celebrities), but Atwell reportedly had her hands insured by the top insurance firm, Lloyds of London, for some £40,000 (figures as high as $120,000 USD were also cited), with a stipulation that she did not wash dishes. But given her fame and Lew's business acumen, there would be no need for her to do so. In late 1952, the couple purchased a home in the North London neighborhood of Whetstone, and either they or the former owner had dubbed it "Green Trees." An article in the November 29, 1953, New York Age, further described the improved situation in her life owing to her talent:

Right now [Winifred] is at the summit of theatreland starring in Bernard Delfont's Folies revue "Pardon My French" at the Prince of Wales Theatre. Playing the classics, boogie, ragtime, and popular melodies, the Trinidad pianist… is making "Pardon My French" Delfont's best revue to date. Co-starring with her is top English comedian Frankie Howard. Add to these two stars a fast moving slick cast of adagios, ballet dancers, singers, beautiful chorines, shapely nudes, handsome males and gorgeous scenery which captures the lyrical beauty of gay Paree and you have a good show as good as better, than anything the French capital could offer…

And now at last she's a top star after years of hard struggle and work. Her weekly salary is in the $5,000 [USD] bracket. She owns a gigantic Cadillac, and elegant Regency house in North London, investments in gilt-edge securities, and is married to Englishman Leo Chesney who manages her business. Her mother and father who sold the family druggist shop in Trinidad now live with her together with her husband's mother.

Some further explanation of her near-instant success came from record producer and sometimes lyricist Norman Newell:

Winnie was around at the right time. Immediately after the war there was a feeling of depression and unhappiness, and she made you feel happy. She had this unique way of making every note she played sound a happy note. She was always smiling and joking. When you were with her you felt you were at a party, and that was the reason for the success of her records.

Performing both live and on radio, Winifred had the luxury of trying out various pieces in multiple genres to see what worked best with her audiences, allowing her to curate the best possible lineup of tunes for each of her records. They were also incorporated into her stage shows, which included Rhythm is Our Business in 1952, and the aforementioned Pardon My French the following season. While these shows were overall good for her image and spreading her fame, there were two appearances overall that cemented her as a pianistic icon in Great Britain and beyond, and meant the world to her.

They were also incorporated into her stage shows, which included Rhythm is Our Business in 1952, and the aforementioned Pardon My French the following season. While these shows were overall good for her image and spreading her fame, there were two appearances overall that cemented her as a pianistic icon in Great Britain and beyond, and meant the world to her.

They were also incorporated into her stage shows, which included Rhythm is Our Business in 1952, and the aforementioned Pardon My French the following season. While these shows were overall good for her image and spreading her fame, there were two appearances overall that cemented her as a pianistic icon in Great Britain and beyond, and meant the world to her.

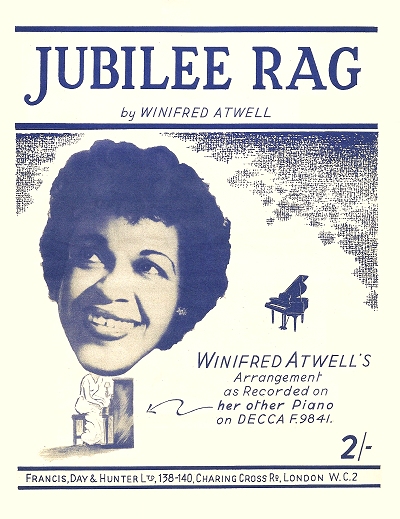

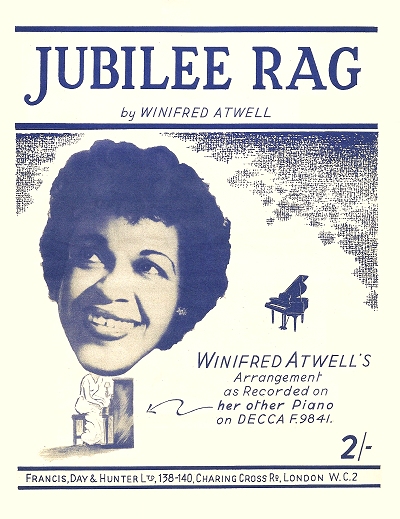

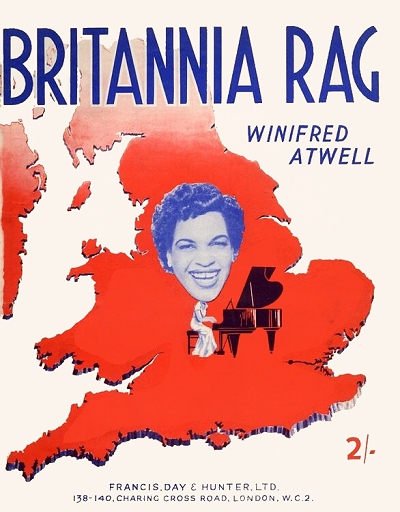

They were also incorporated into her stage shows, which included Rhythm is Our Business in 1952, and the aforementioned Pardon My French the following season. While these shows were overall good for her image and spreading her fame, there were two appearances overall that cemented her as a pianistic icon in Great Britain and beyond, and meant the world to her.On November 3, 1952, Winifred was part of the Royal Variety Command Performance at the London Palladium, the first under the new monarch, Queen Elizabeth. It was also attended by Elizabeth's husband Philip (Duke of Edinburgh) and Princess Margaret. Utilizing both a concert grand and her "other" well-seasoned piano, Winifred dutifully entertained the royalty to great acclaim, and then honored then with her newly composed Britannia Rag. It was actually one of a handful that she had been writing at that time, including Jubilee Rag and Dixie Boogie, the latter based on the American tune Dixie. Presented to the Queen and court after the show, Elizabeth and Margaret, who were also pianists of some ability, showered praise on Winifred, commenting on the joy her records had brought them. Afterwards, she would add the Coronation Rag to her list of originals the following year, commemorating that occasion as well. It reportedly sold some 70,000 copies in its first three weeks in music stores.

While that may seem hard to follow up with any level of excitement, in December 1954, Winifred, whom the press sometimes tritely referred to as a boogie-woogie pianist, performed to a capacity crowd at the Royal Albert Hall, playing Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A Minor with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (the recorded performance appeared on Decca in 1955). This was followed up with George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Both were recorded on multi-track stereo more than three years before that mode would be available on record albums. Having grown weary of being known only for her popular music takes, she reveled in the opportunity, stating, as per the New York Age of December 18, 1954, "I'd have played here for nothing… I had given up the idea of ever coming here as a concert pianist." And now, Winifred Atwell had finally arrived.

playing Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A Minor with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (the recorded performance appeared on Decca in 1955). This was followed up with George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Both were recorded on multi-track stereo more than three years before that mode would be available on record albums. Having grown weary of being known only for her popular music takes, she reveled in the opportunity, stating, as per the New York Age of December 18, 1954, "I'd have played here for nothing… I had given up the idea of ever coming here as a concert pianist." And now, Winifred Atwell had finally arrived.

playing Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A Minor with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (the recorded performance appeared on Decca in 1955). This was followed up with George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Both were recorded on multi-track stereo more than three years before that mode would be available on record albums. Having grown weary of being known only for her popular music takes, she reveled in the opportunity, stating, as per the New York Age of December 18, 1954, "I'd have played here for nothing… I had given up the idea of ever coming here as a concert pianist." And now, Winifred Atwell had finally arrived.

playing Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A Minor with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (the recorded performance appeared on Decca in 1955). This was followed up with George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Both were recorded on multi-track stereo more than three years before that mode would be available on record albums. Having grown weary of being known only for her popular music takes, she reveled in the opportunity, stating, as per the New York Age of December 18, 1954, "I'd have played here for nothing… I had given up the idea of ever coming here as a concert pianist." And now, Winifred Atwell had finally arrived.However, there was often a price to pay with quickly accumulated fame. Part of that for Atwell was the expectation that she perform more of the popular music and less of the longhair numbers. At one point in 1953, the constant appearances and hard work plus some travel caught up with her, and she collapsed on stage following a performance of her Swanee River Boogie at the Prince of Wales Theater. Lew then whisked her off to Madeira, Spain, where she could spend time out of the public eye and regain her strength. There was also the robust recording schedule, which resulted in at least fifteen singles for Decca by 1953, and the release of several albums. Despite her contract with them, she was also signed to make some records for the Dutch label Philips, with two offerings released from 1954 to 1955. The rest for the next several years would be on Decca in the United Kingdom and Australia, and London Records in the United States, as well as their alternative labels Ace of Clubs and Richmond Records.

The rest for the next several years would be on Decca in the United Kingdom and Australia, and London Records in the United States, as well as their alternative labels Ace of Clubs and Richmond Records.

The rest for the next several years would be on Decca in the United Kingdom and Australia, and London Records in the United States, as well as their alternative labels Ace of Clubs and Richmond Records.

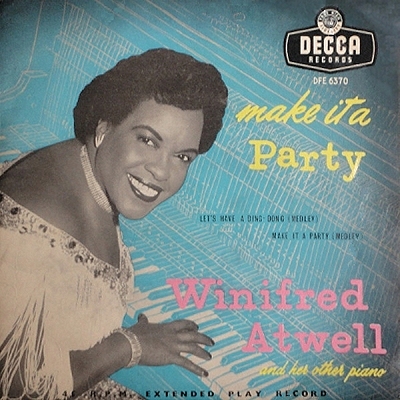

The rest for the next several years would be on Decca in the United Kingdom and Australia, and London Records in the United States, as well as their alternative labels Ace of Clubs and Richmond Records.By now, it is probably clear that given the political and social climate in the United States up through the mid-1950s, it is sadly unlikely that Winifred, being both female and black, would have achieved the level of fame she had now obtained in the United Kingdom, the European continent, and beyond. As a result of that and the number of American artists that started flooding the market with traditional jazz and honky-tonk albums in the mid-1950s, including competition from Carr, Wood, Maddox, and others in a field that she literally "owned" in England, her popularity was largely confined to the black population of the East Coast, giving her no real reason for touring the United States. Even her "party albums," a popular trend at that time, did not make it all that high on the American charts. She did hit number one in 1954 with the single Let's Have Another Party, a logical follow-up to 1953's Lets Have a Party, both medleys of popular old tunes. This made her not only the first female artist to accomplish this, but the first artist of color as well.

She had also done well with coverage of classic rags beyond her own works and Black and White Rag, including recordings of Dill Pickles, Rhapsody Rag, Dynamite Rag, 12th Street Rag and Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag. However, there was yet another continent to conquer, and the Atwells undertook the beginning of that journey in 1955.

|

Sailing aboard the ocean liner Stratheden, Winifred and Lew arrived in Australia in late 1955 to undertake her first tour of the continent down under. Her albums were already fairly well known there, so she was received as a beloved celebrity of the British Empire. Touring on the Tivoli circuit for a few weeks, she received around $5,000 AUS per week, reportedly the highest paid visiting star up to that time. It left a warm impression on the couple, and they would return many times over the next decade and more. Upon her return to England she completed more recordings and made another sold-out appearance at the London Palladium. One of the pieces she recorded at that time was The Poor People of Paris, which became a number one hit for Winifred in the UK, and did well for many others who covered the work in that same period.

Two prospective performances for 1956 did not turn out so well. A planned appearance in New York City for the Ed Sullivan show, broadcast on CBS television,

and which had already launched or boosted many careers since it had gone on the air, ended up not happening. When scoping out the territory after arriving in the states, Winifred and Lew quickly found out that her skin color and British accent were not so conducive to a friendly welcome, particularly in the southeastern part of the country. The various miscegenation laws may have also caused some obstacles. Her first appearance on February 9 was cancelled, but a second one for "England's great jazz pianist… and her crazy piano," was planned for March 4. It is unclear if she actually appeared as advertised, but no recording of her on the stage at his theater is known to exist. It is also possible that the broadcast was preempted in some less than receptive markets. Besides, Americans had their own big star in Vladziu Liberace, who had been frequenting the airwaves. The snub was still a painful sign of the times.

|

Later in the year there was another cancellation on a bigger scale. This was the November 5th, 1956, Royal Variety Performance to which she had been invited once again, along with Viven Leigh and Laurence Olivier. However, there had been skirmishes between British and Egyptian troops along the Suez Canal on November 4th which sent shock waves around the world and divided allegiances throughout the British Commonwealth, to the point where the entire annual celebration was considered moot. Winifred still showed up at Buckingham Palace to give a private house party for the Royal Family, and cheered them up with Roll Out the Barrel and other favorites from her recent albums.

Not that she needed more to do, but Atwell, throughout her travels, had noticed a big gap in the service industry that she felt should be filled. This was the business of hairdressers who focused on the grooming issues of black women looking for proper hair care. To that end, she rented a building at 82A Railton Road near Chaucer Road in Brixton, South London, and in it opened the Winifred Atwell Hair Salon in late 1956. One of the trends they catered to was the straightening of tight curly hair, a look that Winifred had flirted with for some years. Canadian actress Isabelle Lucas who was somewhat of a British television celebrity fondly remembered Winifred in relation to her business:

In those days there were no black salons for black women in [Great Britain]. Black women styled their hair in their kitchens. I needed advice on how to straighten and style my hair, but I didn’t know any black women in Britain. I had only heard about Winifred Atwell. So one day I looked her up in the London telephone directory and found her listed! I rang her, and to my great surprise she answered! I explained my predicament, and she invited me to her home in Hampstead. It was as easy as that! I met her lovely parents ,whom she brought to this country from Trinidad, and Winifred gave me some hair straightening irons.

The salon was open until she sold it in 1961. Winifred also got back into the media that helped to boost her originally, appearing in he own television series in 1956 on Independent Television (ITV) in 1956 for ten episodes, then back to the BBC in 1957. While she played a mix of music, it was usually the ragtime and old-time material that got the most comments and applause. However, by 1958 there was some stiff competition from home-grown rock and roll, which was catching on quickly after its growth across the Atlantic in America. Noticing trends, she tried to adapt as best she could. Along the way discovered a bus driver with some singing ability, and helped him break into show business. Matt Monro became quite the star creating hits like the Bond-themed From Russia with Love. Beyond that, she kept plugging away on stage and television through the 1960s, taking on as much new material as she could while not totally abandoning her bread and butter ragtime pieces. She also appeared at the Brighton Hippodrome in 1962 for an eventful week, and had a radio series titled Pianorama around the same time.

While she played a mix of music, it was usually the ragtime and old-time material that got the most comments and applause. However, by 1958 there was some stiff competition from home-grown rock and roll, which was catching on quickly after its growth across the Atlantic in America. Noticing trends, she tried to adapt as best she could. Along the way discovered a bus driver with some singing ability, and helped him break into show business. Matt Monro became quite the star creating hits like the Bond-themed From Russia with Love. Beyond that, she kept plugging away on stage and television through the 1960s, taking on as much new material as she could while not totally abandoning her bread and butter ragtime pieces. She also appeared at the Brighton Hippodrome in 1962 for an eventful week, and had a radio series titled Pianorama around the same time.

While she played a mix of music, it was usually the ragtime and old-time material that got the most comments and applause. However, by 1958 there was some stiff competition from home-grown rock and roll, which was catching on quickly after its growth across the Atlantic in America. Noticing trends, she tried to adapt as best she could. Along the way discovered a bus driver with some singing ability, and helped him break into show business. Matt Monro became quite the star creating hits like the Bond-themed From Russia with Love. Beyond that, she kept plugging away on stage and television through the 1960s, taking on as much new material as she could while not totally abandoning her bread and butter ragtime pieces. She also appeared at the Brighton Hippodrome in 1962 for an eventful week, and had a radio series titled Pianorama around the same time.

While she played a mix of music, it was usually the ragtime and old-time material that got the most comments and applause. However, by 1958 there was some stiff competition from home-grown rock and roll, which was catching on quickly after its growth across the Atlantic in America. Noticing trends, she tried to adapt as best she could. Along the way discovered a bus driver with some singing ability, and helped him break into show business. Matt Monro became quite the star creating hits like the Bond-themed From Russia with Love. Beyond that, she kept plugging away on stage and television through the 1960s, taking on as much new material as she could while not totally abandoning her bread and butter ragtime pieces. She also appeared at the Brighton Hippodrome in 1962 for an eventful week, and had a radio series titled Pianorama around the same time.In the early 1960s sales of Winifred’s records, which were typically much higher outside of the United States where she never completely caught the general public's ear, began to decline, but she kept turning them out, including a bunch of the for Pye Records in 1962. She continued to undertake tours in Europe and Australia during the 1960s, finding particularly receptive audiences in the latter location. On her third tour of Australia in 1960, Winifred recorded a television series that helped to further spread her fame there. For her Australian tours she brought on native guitarist Jimmy Doyle as a musical director for subsequent tours. By the mid-1960s she had signed with RCA Victor records who released most of her material through the late 1970s. As the decade progressed, she found increasing favor on the southern continent. Attempts to stay relevant included her unique takes on songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the Rolling Stones, and even The Beatles.

As the decade progressed, she found increasing favor on the southern continent. Attempts to stay relevant included her unique takes on songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the Rolling Stones, and even The Beatles.

As the decade progressed, she found increasing favor on the southern continent. Attempts to stay relevant included her unique takes on songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the Rolling Stones, and even The Beatles.

As the decade progressed, she found increasing favor on the southern continent. Attempts to stay relevant included her unique takes on songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the Rolling Stones, and even The Beatles.Another aspect of Atwells life had been a long but not overt battle with weight, and record covers and photographs from the early 1950s into the 1960s showed quite a variance in her appearance. During an unfortunate period of time when weight shaming seemed to be publicly acceptable to some, she embarked on what now would be considered a protein diet, dropping nearly 25% of her body weight by the late 1960s, which clearly shows in later photographs and album covers. Another change in appearance in the late 1960s was her hair. After years of straightening it, Winifred adopted various versions of what was being called an Afro hairstyle, which was retained throughout most of the 1970s.

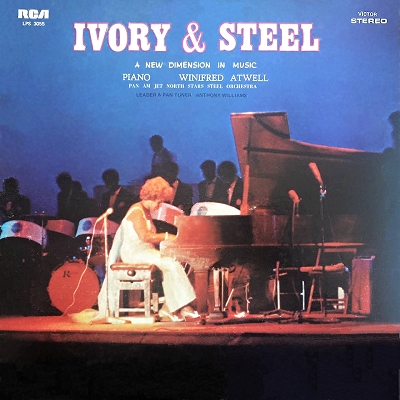

An attempt was made once again to conquer the one hill that Winifred had not yet won. In 1969 she came back to the United States for a few appearances where there was at least some fan base. This included a noteworthy appearance at Carnegie Hall, sponsored by Pan Am Airlines, on November 7, which was reviewed the next day in the New York Amsterdam News:

Winifred Atwell and the Pan Am [Jet] North Star Steel Orchestra had Carnegie Hall rocking with their exciting rhythms last Friday night. Presenting a new dimension in music in ivory and steel, the program offered the sound of the 20th century by artists from the West Indies. They captured the intoxicating rhythms, vitality of the Islands with an ingenuity that was unusual. Miss Atwell’s pianistic virtuosity was a joy to hear and to behold.

Atwell would record the concert with Pan Am group, and it was released by RCA in 1970. Beyond that appearance and a few radio spots, the U.S. was still a largely unobtainable domain for a Caribbean pianist based in London, even during a period when music was undergoing a major shift worldwide to something more global. Throughout this period, Lew was at her side, and may have been a factor in convincing Winifred that her obvious popularity in Australia was not a fluke, and likely a bonus. By late 1970 the decision had been made to relocate, and they would make Sydney their new home.

Beyond that appearance and a few radio spots, the U.S. was still a largely unobtainable domain for a Caribbean pianist based in London, even during a period when music was undergoing a major shift worldwide to something more global. Throughout this period, Lew was at her side, and may have been a factor in convincing Winifred that her obvious popularity in Australia was not a fluke, and likely a bonus. By late 1970 the decision had been made to relocate, and they would make Sydney their new home.

Beyond that appearance and a few radio spots, the U.S. was still a largely unobtainable domain for a Caribbean pianist based in London, even during a period when music was undergoing a major shift worldwide to something more global. Throughout this period, Lew was at her side, and may have been a factor in convincing Winifred that her obvious popularity in Australia was not a fluke, and likely a bonus. By late 1970 the decision had been made to relocate, and they would make Sydney their new home.

Beyond that appearance and a few radio spots, the U.S. was still a largely unobtainable domain for a Caribbean pianist based in London, even during a period when music was undergoing a major shift worldwide to something more global. Throughout this period, Lew was at her side, and may have been a factor in convincing Winifred that her obvious popularity in Australia was not a fluke, and likely a bonus. By late 1970 the decision had been made to relocate, and they would make Sydney their new home.It should be noted at this time the direct influence that Winifred Atwell had over the British public up to the 1970s should not be understated, and she inspired many young musicians of various backgrounds to learn and excel. Two in particular were Reginald Dwight a.k.a. Elton John, and Keith Emerson of the rock group Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Elton had listened to her most of his early life, and fournd her music to be joyous, calling her a hero. In later years Emerson was not shy about citing Winifred's sway over the direction of his eventual career. He spent many hours in his youth at the school piano, since his parents did not have one in the home, and would carefully study what Atwell was playing on her television appearances. Later on, once he became accomplished, he took the initiative to mix other musical genres into the rock and roll mix, including ragtime and classical. This is reflected on the ELP albums of the 1970s, including their own takes on Modeste Moussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, and Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag. In an interview published in 2010 in Keyboard Magazine, Emerson revealed that:

I've always been into ragtime. In England—and I’m sure [fellow keyboard legend] Rick Wakeman would concur—we loved Winifred Atwell, a fantastic honky-tonk and ragtime player.

The process of relocating to the Australian continent was not without its obstacles and issues. The couple had to apply for immigrant status, which evidently was fraught with racial bias for many. Since 1901, the Immigration Restriction Act, put in place to restrict immigration during an Australian gold rush, created what was eventually dubbed the "White Australia Policy." By 1970 there were still remanants of this clearly racist and xenophobic attitude still in place in the provincial government. Whether or not it was fair that Winifred receive special treatment in this regard because of her celebrity status remains debatable, but the Sunday Mirror of February 4, 1971, did not pull punches when it came to these difficulties:

Pianist Winifred Atwell has been given permission to settle down in Australia as an immigrant. She has been told this officially in spite of the country’s 'White Australia' policy. An Australian immigration official said yesterday that she had been granted residence because she was "of good character and had special qualifications." Immigration Minister Mr. Phillip Lynch said: "We will not stand in the way of an international artist of such repute."

The Atwells quickly integrated themselves into Australian life, buying a nice apartment in Collaroy, Sydney, as her new home base, since Winifred still undertook tours in other parts of the world.

She became a member of the Moby Dick Surf Club located at Whale Beach, and gave concerts and recitals there on an ongoing basis. However, as she had observed in America, there was still an issue with racism in Australia concerning not only black people but indigenous ones as well, and battling this or at least bringing attention to it soon became a cause for the pianist as early as the 1960s during her early tours. This included comments she made about Aborigines, who were tacitly victims of a caste system throughout the continent, which made some headlines in 1962 and on later occasions. They had been refused admittance to theaters she was performing in, and she often had to force management's hand to open the doors for them to at least listen to performance from outside. She further advocated for the victims of racism and other injustices, particularly orphaned children, for whom she gave paid concerts each Sunday, donating the proceeds to various charities and assistance groups.

|

There were only a few albums released over the decade, some of them being compilations of Atwells earlier work on Decca. However, Winifred gave performances clear through to 1978, ostensibly in her mid-to-late sixties, including one that was released on RCA Records. While they were visiting Hong Kong in late 1977, Reginald died unexpectedly, leaving her a widow. Playing only occasionally after her 1978 appearances, including a couple of television appearances, Winifred suffered a major stroke in 1980, and was forced to retire. After some recovery Winifred gained Australian citizenship in late 1980. she was now living in Narrabeen a bit north of Sydney. In 1983 her home was destroyed in a fire and she lodged with some friends in nearby Seaforth. It was there that Winifred Atwell suffered a fatal heart attack on February 28, 1983. Lauded as a national treasure of Australia, she was laid to rest at Northern Rivers Memorial Park in South Gundurimba, Lismore City, in New South Wales, Australia.

Winifred Atwell remains important in the overall ragtime legacy for not only adapting a music that was native to the United States into her own style and spreading it throughout the world, but for her tenacity in remaining as a viable performer despite certain racial and gender stigmas of her time. The fact remains that she could outplay most of the performers who were recording during that same time period, including some in the classical and jazz world, and fortunately we still have that part of her legacy still available to us via scores of recordings. And now, it's all there in Black and White.

The bulk of the information in this essay was taken from copious newspaper articles and periodicals, record jacket liner notes, and public records from the United Kingdom and Australia. The age of 73 on Winifred's grave marker provides a further verification that her birth year was likely 1910..

Compositions

Compositions