|

William Conrad Polla (August 12, 1876 to November 4, 1939) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1898

The Jolly Huntsman1899

The Merchant Prince of Cornville: WaltzesTrans-Mississippi Waltzes The Warmest Coon in Darktown [1] 1901

PirouetteThe Great Jumping Jack Series [2] Jumping Jack March Jumping Jack Waltz Jumping Jack Mazurka Jumping Jack Polka Jumping Jack Gavotte Jumping Jack Schottisch Jumping Jack Galop Dolly Series [2] Dolly's Dance Dolly's Minuet Dolly's Lullaby 1902

The Rag Time Laundry [2]The Roll of Thunder: March [2] La Mona (Mona from Arizona) [3] Just for a Dear Little Wife at Home [2,4] On a Moonlight Winter's Night [2,5] Ducky Dear [2,6] When the Lilacs Bloom Again [2,7] We Were Taught From the Same Old Books [8] 1903

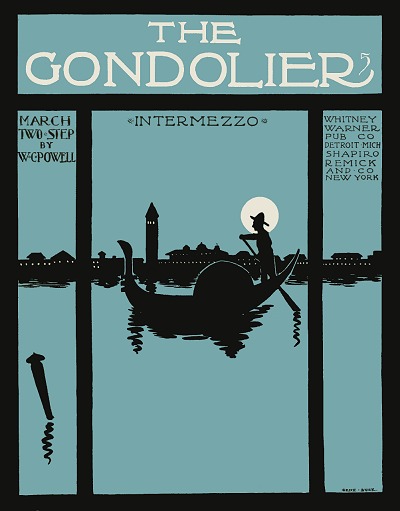

The Gondolier [2]Iolanthe: Intermezzo [2] Virginia Beauties [2] Yoki: A Japanese Two-Step [2] North Winds [2] I've Often Longed to Tell You [2,5] Tell Tale Eyes [2,7,9] 1904

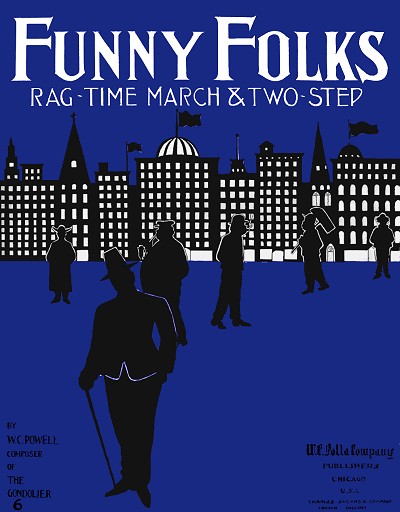

The TroubadourSilks and Satins: Novelette Dixie Doodle [2] Love's Desire: Waltzes [2] Regimental Daughters: March [2] Bubbles [2] Funny Folks [2] Funny Folks (Song) [2,7] Katie from Dublin [2,7] The Gondolier (Song) [2,10] The Troubadour (Song) [2,10] The Black Laugh [11] The Old Tobacco Box: Rube Dance [11] Turkey Feathers [11] Dixie Belles [11] Panama Rag [11] 1905

The Grenadier: Patrol [2]Elaine [6] Black Sheep [2,6] Guess Again [2,6] My Picture of You [2,6] Well, I Could Use Five [2,6] The Girl You Leave Behind [2,6] My Babe of the Bungalow [2,6] Over Sunday [2,6] My Indian Summer Moon [2,6] On Independence Day [2,6] Georgianna [2,6] In Dear Old Grandma's Day [2,6] The Last of His Regiment [12] Mary Wise [2,6,13] They Sent for Me- [2,6,14] 1906

Evening Shadows [2]Cinderella [2] Dixie-Doodle Girl (aka Dixie Doodle?) [2] Fascination: Intermezzo [2] Holy Moses [11] 1907

Mignon: NoveletteThe Lonely Wanderer Missouri Rag [2] The Weary Wanderer [2] La Gazelle [2] Ragtime Eyes [2] Jolly Jingles [2] Exposition March [2] Twinkles: Three Step [2] Cinderella: Song [2,6] If You Were Only Here Tonight [2,6,13] Hello Bill [2,15] While You are Mine [2,16] I've Taken a Liking to You [2,16] 1908

The Haymaker's Barn Dance [2]The Tarantula: A Texas Rag [2] Blinking Moon: Three Step [2] Broadway Rag [2] Scented Posies: A Salon Piece [2] Sweet Violets: Intermezzo [2] Prince Charming: Ballet Petite [2] For You, Dear Heart [2,6] 1909

Curly: IntermezzoDope: Rag Novelette [2] Bachelor's Button [2] Azure Skies: Reverie [2] Forty Winks: Intermezzo [2] Right About [2] The School March [2] The Harvest Moon [2] Silvery Moonlight: Three Step [2] Honey Moon Waltz [2] Water-Cress [2] Betty and Billy: Waltzes [2] Princess May [2] Sunbeam: Intermezzo [2] Cincinnati Rag [2] Cucumber Rag [2] Clover Leaf Rag [11] Curly: Song [17] 1910

Little Soldier: March [2]Goldenrod: Flower Dance [2] Irresistible: Rag [2] Johnny Jump Up [2] Buds and Blossoms: Waltz [2] Blue Bird Waltz [2] Dream Waltz [2] Cavalieri: Spanish Serenade [2] Cucumber Rag [2] Sunrise on the Lake: Reverie Waltz [2] Clover Leaf: Idyl [2] Forest Voices: Idyl [2] Vedana: Intermezzo [2] Sylvan Dell: Reverie [2] Whispers in the Dell: Tone Poem [2] A China Clock and A Dresden Cat [2,7] 1911

The Buttercup: Idyl[2]Recess Time [2] Messenger of Love: Tone Poem [2] The Angel of Love: Reverie [2] Marine Four Step [2] The Jessamine [2] Cairo: Intermezzo Patrol [2] Dance of the Dragons: Grand Galop de Concert [2] Musical Rag-Time Sal [2,18] It Isn't Hard to Love a Girl Like You [2,18] Flower Land [7] The Marigold; The Lilac; The Lily; The Lady Slipper; The Orchid; The Larkspur; The Posy; The Rose; The Snow Drop; The Violet Rose Songs (Opus 3:1-5) [7] The Rose and the Wind The South Wind and the Rose Go Fragrant Rose The Mission of the Rose The Rose and the Star 1912

Jack and Jill: March [2]Cosette: Waltz [2] When a Lovable Girl Loves You [2,18] Somewhere in Dixie Lives the Girl I Love [2,18] |

1912 (Cont.)

The Dope Rag (Song) [2,19]The Three Graces [Opus 1:1-3] Faith; Hope; Charity 1913

Normandy Chimes [2]Rose Waltz [2] Laughing Eyes [2] The Woman Thou Gavest Me [2,20] Hop, Hop, Hop [2,21] Love Knots [2,22] 1914

Fascination con Amore (Valse) [2]Hesitiation con Amore (Valse) [2] Overture Potpourri - A Moving Picture Operetta [2] Would You Take a Chance with Me? [20] 1915

Br'er Fox [2]Valse Coquette [2] Flowerland: Waltzes [2] Why Do You Make Me Want You? [20] There's a Key to Every Heart [23] Br'er Fox: Song [23] My Land of Romance: Arabia [24] 1916

The Rose That Never Fades [2]When Evening Shadows Fall [25] That Was My Mother's Good Night Song [25] Hula Boola Boo [26] 1917

Hail to Victory [2]Do You Really Care? [27] God Save America [28] 1919

You Know (I Love You) [2,31]Buddy [5] Yo-San [5] Wings of the Morning [5] Dear Heart [7,32] I'll Be Glad to Get Back [18,29] Arabia: Land of Romance [18,30] If You Would Care for a Lonely Heart [33] My Castles in the Air are Tumbling Down [33] Harem Eyes [33] Pride of the Caravan [33] Drifting [33] I Want a Dixie Sweetheart [34] My Garden of Love [35] The Dawn of Love [36] Supposing [37] Two Sweethearts of Mine [37] I Want to Love Someone Like You [37] Why Do they Call Mama Poor Butterfly? [38] Typhoon: A Love Storm [39] 1920

Carmenella: A Spanish RomanceMy Sunshine Rose [7] School Pals [33] Do You Really Want Me As I Want You? [33] Girl of My Dreams [40,41,42] My Mother [44] One Precious Day [44] 1921

Garden of Smiles [21](Everybody Calls Her) Baby [40,41] Mary O'Brien [40,41] I'd Love to Be in Ireland, the Day They Set Old Ireland Free [41,43] Toys are Not Only for Children [44] In the Heart of the Lehigh Valley [44] The Land of Hearts and Flowers [44] 1922

Without You [45]1923

Just Like a Baby (That Cries for theMoon) [40,46] 1924

Tell Me What to Do [47]1925

Chink: Mongolian Fox-TrotArabian Romance: Dvorak Fox-Trot Folia: Caprice Why Do You Haunt Me So? [23] The Melody That Made You Mine [48] 1926

Some Day [49]1927

Dancing Tambourine [2]Dancing Tambourine (Song) [2,22] Linger Longer [50] 1929

Just a Kiss at Twilight (The Night We SaidGood-Bye) [51] 1930

Boy Scouts on Parade [2]Camping [2] My Garden [2] My Dickey Bird [2] My Temptation [52] 1931

Two Guitars1933

Old Mother Hubbard [41]1935

Spanish Butterfly [53]1936

My America, My Homeland (Unp) [7]

1. w/John Allen

2. as W.C. Powell 3. w/Al Fredericks 4. w/Oliver Roday 5. w/Jean Lefavre 6. w/James O'Dea 7. w/Clarence Patrick (C.P.) McDonald 8. w/James Smith 9. w/S.E. Kiser 10. w/Harry Williams 11. as C. Seymour or Cy Seymour 12. w/Edward J. Madden 13. w/William Dailey 14. w/John W. Rehauser 15. w/Arthur Longbrake 16. w/Harry D. Kerr 17. George Totten Smith 18. w/Martin Swanger (or Swauger) 19. w/S. Rosen 20. w/Will D. Cobb 21. w/Ewart McKinnon 22. w/Lettie Gould 23. w/Grace Newell 24. w/Ben Richmond & Robert F. Roden 25. w/Jeff Branen 26. w/Alex Gerber 27. w/Sadie E. Rowan 28. w/Charles F. Lee 29. w/R.H. Wilson 30. w/Cohen Meyer 31. w/Phil Ponce 32. w/Willard Goldsmith 33. w/Arthur J. Lamb 34. w/Jack Gartland 35. w/Ella Smith 36. w/Margaret Clair Beutinger 37. w/Frederick Moxon 38. w/Louis Seifert 39. w/James Kendis & James Brockman 40. w/Harry Tobias 41. w/Charles Tobias 42. w/Henry Tobias 43. w/Eddie Cantor 44. w/Amy Ashmore Clark 45. w/Walter Baker 46. w/Arthur Kurtz as Arthur Short 47. w/Jesse Winne 48. w/Cliff Friend 49. w/Larry Spier 50. w/Robert Levenson & George Lipschultz 51. w/Lou Klein 52. w/Norman Clark 53. w/Alfred Bryan |

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |

|

1924

I'll Get You [1]Too Tired [1] Nightingale [1] Lazy Waters [1] Traveling Blues [1,2] All Alone with You [1] I'll See You In My Dreams [1,3] The Only Only One [1,3] 1925

You and I [1]Deep in My Heart, Dear [1] How I Love That Girl [1,4] Waltz My Lightly, Hold Me Tightly [1] Will You Remember Me? [1,5] I Don't Want to Get Married [1,3] China Girl [1,3] Moonlight and Roses [1,6] When You and I Were Seventeen [1,6] Kickin' the Clouds Away [1,7] Why Do I Love You So? [1,7] Tell Me More [1] The Time Will Come [1] The Melody that Made You Mine [1] Isn't She the Sweetest Thing? [1] Madeira [1] Save Your Sorrow For Tomorrow [1] I Want a Lovable Baby [1,7] Give Us the Charleston [1,7] Beside a Silv'ry Stream [1] One Smile [1] Silver Head [1,4] The Promenade Walk [1] I Want You All for Me [1,7] I Left Her By the Shores of Minnetonka [1,7] Kammanoi-Ostrow [1] Arabian Romance [1] Bam, Bam, Bamy Shore [8] Don't Wait Too Long [8] Normandy [8] Show Me the Way to Go Home [1] Sugar Plum [1] Lucky Boy [1] Sugar Plum [1,9]

1. as Polla's Clover Garden Orchestra

2. w/Will Prevost 3. also as Hannan Dance Band 4. w/Vernon Dalhart, vcl. 5. w/George Wilton Ballard, vcl. |

Matrix and Date

[Edison 9848] 11/15/1924[Edison 9849] 11/15/1924 [Edison 9880] 11/29/1924 [Edison 9881] 11/29/1924 [Edison 9886] 12/03/1924 [Edison 9887] 12/03/1924 [Columbia 140197] 12/19/1924 [Columbia 140198] 12/19/1924 [Edison 9953] 01/21/1925 [Edison 9954] 01/21/1925 [Edison 9996] 02/10/1925 [Edison 9997] 02/10/1925 [Columbia 140392] 02/25/1925 [Columbia 140393] 02/25/1925 [Edison 10308] 04/09/1925 [Edison 10309] 04/09/1925 [Columbia 140545] 04/22/1925 [Columbia 140546] 04/22/1925 [Edison 10345] 04/30/1925 [Edison 10346] 04/30/1925 [Edison 10405] 05/27/1925 [Edison 10406] 05/27/1925 [Edison 10459] 06/24/1925 [Edison 10460] 06/24/1925 [Columbia 140740] 07/01/1925 [Columbia 140741] 07/01/1925 [Edison 10483] 07/02/1925 [Edison 10484] 07/02/1925 [Edison 10511] 07/22/1925 [Edison 10512] 07/22/1925 [Columbia 140804] 08/03/1925 [Columbia 140805] 08/03/1925 [Columbia 140885] 09/01/1925 [Columbia 140886] 09/01/1925 [Harmony 141108] 10/05/1925 [Harmony 141109] 10/05/1925 [Harmony 141110] 10/05/1925 [Edison 10659] 10/29/1925 [Edison 10660] 10/29/1925 [Columbia 141269] 11/17/1925 [Columbia 141270] 11/17/1925

6. w/Helen Clark & Joseph Phillips, vcl.

7. also as Denza Dance Band 8. as Harmony Dance Orchestra 9. w/Gertrude Lawrence, vcl. |

William C. Polla was born to immigrant German parents William Polla and Babetta Schill (Babetta was later Anglicized to Elizabeth) in New York City during the Centennial year of the United States, 1876. The family name was originally Polle as shown in the 1870 and 1880 census records. William Jr. also had one sister, Theresa, a bit over a year younger than himself. William Sr. worked in a piano factory and possibly as a technician (he is shown as a piano maker in the 1870 enumeration and a piano workman in 1880), so William Jr. was definitely exposed to pianos and their musical possibilities at an early age.

It is hard to discern if any of Polla's musical training came from his father. However, his formal education included harmony and theory along with orchestration at the Chicago Conservatory, followed by a time at the New York College of Music. His primary instrument was piano, and he proved his skill on it particularly in the 1920s when recording some of his pieces, but William was also well versed in organ performance. Although he was gifted as a classical performer, Polla's first published composition was The Jolly Huntsman, a typical march of the time, when he was 22. Polla was married in 1898 to rising operatic singer Pauline M. Stripe, a few months younger than himself. They had one daughter, Helen, born on January 24, 1901. The family was living in Manhattan as of the 1900 census, his occupation listed simply music. William was also working part-time in vaudeville for Frank Cushman, billed in the act as "Professor W.C. Polla."

followed by a time at the New York College of Music. His primary instrument was piano, and he proved his skill on it particularly in the 1920s when recording some of his pieces, but William was also well versed in organ performance. Although he was gifted as a classical performer, Polla's first published composition was The Jolly Huntsman, a typical march of the time, when he was 22. Polla was married in 1898 to rising operatic singer Pauline M. Stripe, a few months younger than himself. They had one daughter, Helen, born on January 24, 1901. The family was living in Manhattan as of the 1900 census, his occupation listed simply music. William was also working part-time in vaudeville for Frank Cushman, billed in the act as "Professor W.C. Polla."

followed by a time at the New York College of Music. His primary instrument was piano, and he proved his skill on it particularly in the 1920s when recording some of his pieces, but William was also well versed in organ performance. Although he was gifted as a classical performer, Polla's first published composition was The Jolly Huntsman, a typical march of the time, when he was 22. Polla was married in 1898 to rising operatic singer Pauline M. Stripe, a few months younger than himself. They had one daughter, Helen, born on January 24, 1901. The family was living in Manhattan as of the 1900 census, his occupation listed simply music. William was also working part-time in vaudeville for Frank Cushman, billed in the act as "Professor W.C. Polla."

followed by a time at the New York College of Music. His primary instrument was piano, and he proved his skill on it particularly in the 1920s when recording some of his pieces, but William was also well versed in organ performance. Although he was gifted as a classical performer, Polla's first published composition was The Jolly Huntsman, a typical march of the time, when he was 22. Polla was married in 1898 to rising operatic singer Pauline M. Stripe, a few months younger than himself. They had one daughter, Helen, born on January 24, 1901. The family was living in Manhattan as of the 1900 census, his occupation listed simply music. William was also working part-time in vaudeville for Frank Cushman, billed in the act as "Professor W.C. Polla."Around 1901 the Pollas relocated to Chicago, Illinois. William had already been working as a free-lance arranger for various publishers, with some pieces issued under the banner of publisher Sol Bloom as early as 1899. He obviously caught the composing bug somehow because starting in 1901 there was a steady stream that flowed from his pen for more than 25 years. Among his earliest works were two suites for younger players encompassing several musical dance styles of the prior century. Starting with this series and continuing with many of his popular compositions, which in 1902 were started with The Ragtime Laundry, Polla, who had already altered the family name from Polle, chose to issue many of his works under his first of two pseudonyms, the thinly-veiled and Americanized W.C. Powell. There are a few possible reasons for this as with other composers who did the same thing, but given how the name was applied, it seems evident that William wanted the more serious pieces associated directly with his European name, and the frivolous or popular pieces with the Anglicized version.

By 1903 Polla was working for Chicago publisher Victor Kremer. Kremer copyrighted his series of Jumping Jack and Dolly tunes, which had been copyrighted in 1901. They were reprinted in folios in 1912, but the early Kremer versions are very rare. Polla had a few other pieces published by Kremer during his time with that company, but had no particular allegiance to any one publisher. Indeed, his first self-named firm, the W.C. Polla Company, was established in either 1903 or 1904 in the Grand Opera House block, even though he was still working for Kremer. Among the first works he released were some written with lyricist Clarence Patrick (C.P.) McDonald, with whom he would have a multi-decade relationship,. He also issued some syncopated instrumentals by other Chicago composers, often billed as the arranger.

Indeed, his first self-named firm, the W.C. Polla Company, was established in either 1903 or 1904 in the Grand Opera House block, even though he was still working for Kremer. Among the first works he released were some written with lyricist Clarence Patrick (C.P.) McDonald, with whom he would have a multi-decade relationship,. He also issued some syncopated instrumentals by other Chicago composers, often billed as the arranger.

Indeed, his first self-named firm, the W.C. Polla Company, was established in either 1903 or 1904 in the Grand Opera House block, even though he was still working for Kremer. Among the first works he released were some written with lyricist Clarence Patrick (C.P.) McDonald, with whom he would have a multi-decade relationship,. He also issued some syncopated instrumentals by other Chicago composers, often billed as the arranger.

Indeed, his first self-named firm, the W.C. Polla Company, was established in either 1903 or 1904 in the Grand Opera House block, even though he was still working for Kremer. Among the first works he released were some written with lyricist Clarence Patrick (C.P.) McDonald, with whom he would have a multi-decade relationship,. He also issued some syncopated instrumentals by other Chicago composers, often billed as the arranger.William's first truly popular hit as W.C. Powell was The Gondolier in 1903. It was published by the large Whitney-Warner firm, which was run at that time by composer Charles N. Daniels and had recently been acquired by Jerome H. Remick. The Gondolier had lyrics added the next year to further sales, a common practice with popular instrumentals of all types at that time, and one of a number of Powell pieces for which this would occur. In 1904 Polla added the more rural sounding Cy Seymour as a pseudonym identity, but used it for only a smattering of pieces. The most popular of these were Clover Leaf Rag and Holy Moses. His response, as Powell, to the St. Louis Fair was a good seller, the self-published Funny Folks. Polla had rejected a $10,000 offer to publish that piece, and ended up making considerably more through his own issue. It was enough to urge him to release it as a song with lyrics by McDonald.

By 1904, Polla was also doing some orchestral arranging of works for Kremer, and in many cases updating older classical tunes into a more palatable form for a 20th century crop of pianists to consume. In late 1904, possibly due to the illness and subsequent death of his mother, William sold his own Chicago catalog to publisher W.A. Thompson, then moved back to Manhattan to work as the New York representative and manager of the Kremer firm. In 1905 he also incorporated the Polla-Powell Publishing Company on 28th Street in the heart of "Tin Pan Alley," started with a capital of $5,000. Through his submissions and works put out by his own publishing company Polla caught the attention of Remick managers, possibly Daniels, who hired him as an arranger around 1906, with Jens Bodewalt Lampe, a composer and arranger of similar caliber, as his assistant.

Through his submissions and works put out by his own publishing company Polla caught the attention of Remick managers, possibly Daniels, who hired him as an arranger around 1906, with Jens Bodewalt Lampe, a composer and arranger of similar caliber, as his assistant.

Through his submissions and works put out by his own publishing company Polla caught the attention of Remick managers, possibly Daniels, who hired him as an arranger around 1906, with Jens Bodewalt Lampe, a composer and arranger of similar caliber, as his assistant.

Through his submissions and works put out by his own publishing company Polla caught the attention of Remick managers, possibly Daniels, who hired him as an arranger around 1906, with Jens Bodewalt Lampe, a composer and arranger of similar caliber, as his assistant.Through these two considerable talented individuals, the arranging and composing departments of Remick turned out music that was not only harmonically coherent and user-friendly, but also nearly error free. In the early 1910s multiple interviews revealed that this department conducted their work without a piano in the room, a fact which attests to the skill of the personnel Polla and Lampe hired and trained. William was also turning out a wide range of songs and intermezzos interspersed with piano rags, many of them with stunning cover art. There were also some pieces for smaller hands or pianists of lower grades, with a number of them issued in 1907. It was also clear that Polla was somewhat independent as a composer since he used a variety of lyricists rather than working as a consistent team like many of his contemporaries.

On the side, Polla was also getting work as a performer and a conductor, although there are few notices about his earlier appearances remaining in trade papers. He had also continued to run his own publishing enterprises, and in 1908 was incorporated once again, this time with another publisher, P.J. Howley, who had issued his works with his former company, Howley, Haviland and Dresser. They formed Howley, Polla & Company with an initial capital of $1,000, but he was still located in publisher's row, also known as "Tin Pan Alley," on 28th Street. Polla still worked as a free-lance arranger as well, even reworking some older American tunes and simplified piano renditions of classical works for publishers such as Morris Music in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In 1910, Polla showed up in the Federal census, oddly enough, as Jefferson Polla, although still married to Pauline. An explanation for this temporary identity change is hard to discern, but it may have simply been an enumerater error, since his correct name is present in the New York City directory. What was becoming obvious was one of his more enjoyable hobbies; that of raising and studying flowers. His first floral pieces show up in 1910, followed in 1911 by a set of rose songs set to the poems of McDonald, and another suite encompassing several varieties of flowers. This was followed by another suite, this time religious, of the Three Graces. In a sense, Polla was staying true to his classical roots and presenting an American form of Art Song, with a number of his solo pieces designated as tone poems. In addition, he was taking some works of the 19th century and rearranging them with his own variations for issue, including marches, waltzes and parlor pieces. When W.C. Handy came to New York, he utilized Polla to arrange tunes for band and orchestra, raising the level of many common blues tunes to one of great interest and content to a wider audience. Pauline continued to enjoy her own career as an opera singer, especially performing the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Over the next few years she would take to the silver screen as well, appearing in a number of silent films, most for the Famous Lasky Players.

His first floral pieces show up in 1910, followed in 1911 by a set of rose songs set to the poems of McDonald, and another suite encompassing several varieties of flowers. This was followed by another suite, this time religious, of the Three Graces. In a sense, Polla was staying true to his classical roots and presenting an American form of Art Song, with a number of his solo pieces designated as tone poems. In addition, he was taking some works of the 19th century and rearranging them with his own variations for issue, including marches, waltzes and parlor pieces. When W.C. Handy came to New York, he utilized Polla to arrange tunes for band and orchestra, raising the level of many common blues tunes to one of great interest and content to a wider audience. Pauline continued to enjoy her own career as an opera singer, especially performing the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Over the next few years she would take to the silver screen as well, appearing in a number of silent films, most for the Famous Lasky Players.

His first floral pieces show up in 1910, followed in 1911 by a set of rose songs set to the poems of McDonald, and another suite encompassing several varieties of flowers. This was followed by another suite, this time religious, of the Three Graces. In a sense, Polla was staying true to his classical roots and presenting an American form of Art Song, with a number of his solo pieces designated as tone poems. In addition, he was taking some works of the 19th century and rearranging them with his own variations for issue, including marches, waltzes and parlor pieces. When W.C. Handy came to New York, he utilized Polla to arrange tunes for band and orchestra, raising the level of many common blues tunes to one of great interest and content to a wider audience. Pauline continued to enjoy her own career as an opera singer, especially performing the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Over the next few years she would take to the silver screen as well, appearing in a number of silent films, most for the Famous Lasky Players.

His first floral pieces show up in 1910, followed in 1911 by a set of rose songs set to the poems of McDonald, and another suite encompassing several varieties of flowers. This was followed by another suite, this time religious, of the Three Graces. In a sense, Polla was staying true to his classical roots and presenting an American form of Art Song, with a number of his solo pieces designated as tone poems. In addition, he was taking some works of the 19th century and rearranging them with his own variations for issue, including marches, waltzes and parlor pieces. When W.C. Handy came to New York, he utilized Polla to arrange tunes for band and orchestra, raising the level of many common blues tunes to one of great interest and content to a wider audience. Pauline continued to enjoy her own career as an opera singer, especially performing the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Over the next few years she would take to the silver screen as well, appearing in a number of silent films, most for the Famous Lasky Players.After several fruitful years with the Remick Corporation, Polla reestablished his own publishing house. In the late winter of 1915 he incorporated W.T. Polla & Company with a capital stock of $10,000, then soon abandoned that post to work as an arranger for his old partner, owner of the P.J. Howley Music Company. In 1916 Polla once again reestablished his publishing house at 1547 Broadway in Manhattan with Howley as his primary distribution and selling agent. The W.C. Polla Company, which managed to stay in business for several years, utilized magnificent covers of the floral and beautiful girl varieties to create multi-media artworks. He published works by many of his colleagues as well, most of them arranged by Polla. There was a mix of works from the mid-1910s into the 1920s under both Polla and Powell, and his true identity became somewhat confused in copyright records of that period, with some of them showing Polla to be a pseudonym of Powell, rather than the other way around. The source of this ongoing juxtaposition was not found, but it was likely at the Library of Congress copyright office.

There is a clear lack of compositional output from Polla's own hand during World War One, 1917-1918, with only three that were found in 1917, and none in 1918. However, it does not appear likely that William served in the conflict at that time, at least not overseas, so he may have been involved in other efforts such as leading groups, given the number of bandleaders that were called to serve at that time, creating many vacancies to fill for the duration. After the war, many of Polla's pieces from 1919 into early 1920s were illustrated by Rolf Armstrong, a contemporary of Remick's beautiful girl artist Frederick S. Manning. Using four and five color covers to create a beautiful palette, and with a variety of charming young women as his subjects, Armstrong would go on to be known as the father of "pin-up art" given his considerable skill at capturing beauty.

Using four and five color covers to create a beautiful palette, and with a variety of charming young women as his subjects, Armstrong would go on to be known as the father of "pin-up art" given his considerable skill at capturing beauty.

Using four and five color covers to create a beautiful palette, and with a variety of charming young women as his subjects, Armstrong would go on to be known as the father of "pin-up art" given his considerable skill at capturing beauty.

Using four and five color covers to create a beautiful palette, and with a variety of charming young women as his subjects, Armstrong would go on to be known as the father of "pin-up art" given his considerable skill at capturing beauty.While Polla continued to ply his own skills with his artful and classically-styled works, from time to time he also turned out a neat raggy tune or popular ballad as well. There was a flurry of works put out in the initial postwar period with lyricists Arthur J. Lamb and Frederick Moxon, plus some more floral pieces with McDonald. The names Polla and Powell seemed ever more interchangeable, but it appears that he applied his own name to the more serious works and ballads, while utilizing Powell for popular tunes with his frequent lyricists. One of the finest of these collaborations of 1919 came with Dear Heart, a big hit for Polla, with a beautiful unsigned cover that was a contributing factor to sales. His prolific return to composition in 1919 with this particular work was notable, and even made the press, as noted in the New York Clipper of July 9: "W.C. (Bill) Polla, the composer, whose 'Gondolier' hit a high mark in the music world a dozen years ago, is writing again. Just to show that he has lost none of his old-time ability to hit the taste of music lovers his latest number, 'Dear Heart,' has hit the 400,000 sale figure." By that time Polla was working as an arranger and music editor in the New York office of Hartford, Connecticut, publisher C.C. Church & Company.

The 1920 enumeration showed Polla as still married yet living on his own. Pauline, who was enjoying her career as a movie actress in addition to occasional operatic appearances, had evidently physically separated from her husband by this time, yet after her death a few months after Polla's demise he was still cited as being her husband given that she kept his last name throughout her career. That year saw another fine hit, Drifting, which was a follow-up to Dear Heart. In June of 1921, Polla resigned from the Church firm and opened up yet another of his publishing houses, this time focused on free-lance arranging. It was located with many other smaller firms in the Strand Theater Building in the Broadway District of Manhattan.

After 1921 Polla took another break from frequent writing and publishing, and started leading his own orchestra for three years, making a series of popular recordings bordering on jazz at times. Approaching 50, he formed Polla's Clover Garden Orchestra, which performed regularly at the Clover Garden in New York [note that there were other Clover Garden orchestras named after this venue as well]. For a year from December 1924 to December 1925 they made 42 recordings on Columbia, Edison and Harmony records. A few of the Columbia sides were inexplicably reissued as either the Hannan Dance Band or the Denza Dance Band. His fine dance tune arrangements from these recordings, as well as for other groups, were distributed from time to time, and were featured by many other fine orchestras. Following a period of touring, recording and regular performing in Manhattan, the Polla orchestra disbanded at the end of 1925 and he went back to writing and arranging full time. Polla also became the musical director of New York radio station WGCP for some time, and was heard often on the radio directing groups of many different makeups for several years. William finally became a member of ASCAP in 1926, 12 years after it had been founded by many of his peers.

which performed regularly at the Clover Garden in New York [note that there were other Clover Garden orchestras named after this venue as well]. For a year from December 1924 to December 1925 they made 42 recordings on Columbia, Edison and Harmony records. A few of the Columbia sides were inexplicably reissued as either the Hannan Dance Band or the Denza Dance Band. His fine dance tune arrangements from these recordings, as well as for other groups, were distributed from time to time, and were featured by many other fine orchestras. Following a period of touring, recording and regular performing in Manhattan, the Polla orchestra disbanded at the end of 1925 and he went back to writing and arranging full time. Polla also became the musical director of New York radio station WGCP for some time, and was heard often on the radio directing groups of many different makeups for several years. William finally became a member of ASCAP in 1926, 12 years after it had been founded by many of his peers.

which performed regularly at the Clover Garden in New York [note that there were other Clover Garden orchestras named after this venue as well]. For a year from December 1924 to December 1925 they made 42 recordings on Columbia, Edison and Harmony records. A few of the Columbia sides were inexplicably reissued as either the Hannan Dance Band or the Denza Dance Band. His fine dance tune arrangements from these recordings, as well as for other groups, were distributed from time to time, and were featured by many other fine orchestras. Following a period of touring, recording and regular performing in Manhattan, the Polla orchestra disbanded at the end of 1925 and he went back to writing and arranging full time. Polla also became the musical director of New York radio station WGCP for some time, and was heard often on the radio directing groups of many different makeups for several years. William finally became a member of ASCAP in 1926, 12 years after it had been founded by many of his peers.

which performed regularly at the Clover Garden in New York [note that there were other Clover Garden orchestras named after this venue as well]. For a year from December 1924 to December 1925 they made 42 recordings on Columbia, Edison and Harmony records. A few of the Columbia sides were inexplicably reissued as either the Hannan Dance Band or the Denza Dance Band. His fine dance tune arrangements from these recordings, as well as for other groups, were distributed from time to time, and were featured by many other fine orchestras. Following a period of touring, recording and regular performing in Manhattan, the Polla orchestra disbanded at the end of 1925 and he went back to writing and arranging full time. Polla also became the musical director of New York radio station WGCP for some time, and was heard often on the radio directing groups of many different makeups for several years. William finally became a member of ASCAP in 1926, 12 years after it had been founded by many of his peers.Polla's biggest hit of the 1920s came in 1927 when he was age 51. The Dancing Tambourine was a novelty work that was quickly picked up by many top pianists and bandleaders of the era, including Paul Whiteman, and made piano roll appearances as well. It reestablished Polla as a novelty pianist and composer, although this was a short-lived contention as Polla more or less retired from composition late in the year, and arranging within the next few years. Only a handful of compositions would appear over the next nine years. Just the same, William's name popped up often in the trades during the mid to late 1920s, largely for his fine arrangements. In 1928 and 1929 he was seen working for the Charles Bayha Music Publishing Company and the Triangle Music Publishing Company, mostly doing orchestrations.

By 1930 Polla had remarried - or possibly remarried - to Hazel Purdy. They appeared together in the 1930 census both living at 210 West 101st Street in Manhattan in the same apartment, and as married, but under separate names with Hazel as head of household and W.C. as a lodger. It may have been a common law marriage made official at some point, or Hazel was ahead of her time, keeping her maiden name for professional or personal reasons. However, at the time of William's death in late 1939 at age 63, she was cited as Hazel Purdy Polla. His former wife, Pauline Polla, died just a few months later in April of 1940 at their daughter's New York home.

William C. Polla had a significant impact on the early years of the music industry, not only contributing some notable works that still endure, but setting high standards that challenged other publishers and musicians to follow through at the same level. As with many arrangers of his stature, we will never know of all the works he touched, but his musical DNA was clearly a part of New York's production of popular music for more than two decades during the initial growth music as an industry in America.